9,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

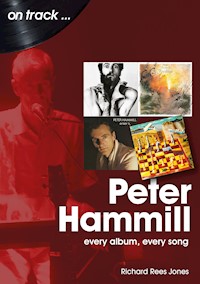

- Herausgeber: Sonicbond Publishing

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Serie: On Track

- Sprache: Englisch

The British singer, songwriter and musician Peter Hammill is one of the key figures in the history of progressive rock. As the leader and main creative force of Van der Graaf Generator, he was behind some of the most powerful and compelling rock music of the 1970s, and since VdGG reformed in 2005 has continued to lead the group down a unique musical path.

But Van der Graaf Generator are only part of the Peter Hammill story. Beginning with 1971’s Fool’s Mate and continuing all the way to 2021’s In Translation, Hammill has carved out a lengthy solo career consisting of some 35 albums, plus many live albums and collaborations. The range of styles in evidence on these albums is remarkable, from baroque progressive rock to snotty proto-punk, angular new wave, delicate ballads, electronic experiments and he even wrote and recorded a full-length opera.

This is the first book to offer an in-depth exploration of Peter Hammill’s solo discography, revealing the sonic intensity and emotional turmoil that lie at the heart of his work. The book is an invaluable companion to Dan Coffey’s Van der Graaf Generator On Track.

Richard Rees-Jones lives in Geneva, Switzerland, where he works for an international organization. He previously lived in Vienna and wrote the chapter on music for the Time Out Guide to Vienna. He has also written album reviews for the acclaimed music website The Quietus and for The Sound Projector magazine. He comes from Salisbury, south-west England, and studied English at Sussex University. He is married with two children. This is his first book.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 343

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

Sonicbond Publishing Limited

www.sonicbondpublishing.co.uk

Email: [email protected]

First Published in the United Kingdom 2021

First Published in the United States 2021

This digital edition 2022

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data:

A Catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Copyright Richard Rees Jones 2021

ISBN 978-1-78952-163-4

The right of Richard Rees Jones to be identified

as the author of this work has been asserted by him

in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission in writing from Sonicbond Publishing Limited

Printed and bound in England

Graphic design and typesetting: Full Moon Media

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Seán Kelly, Boris Lulinsky, Andrew Wales and the other members of the Top of the World Club for always fun and stimulating Hammill-related discussions, for useful insights into several songs, and for saving me a place at Café Oto.

Hello to friends in Vienna: John Stewart, Geraint Williams, Nicholas Ward. Here’s hoping for a reunion sometime.

Hello across the ocean to Duane Capizzi, the world’s most dedicated Hammill, Brötzmann, Braxton and Parker fan.

Eternal thanks to Peter Hammill for the music, and for a Sunday afternoon walk in Freshford after the flood.

Love and kisses, always and forever, to Maeve and Emma.

This book is dedicated to Ben.

as though he never knew the meaning of the words until just now

Contents

Introduction

Fool’s Mate (1971)

Chameleon in the Shadow of the Night (1973)

The Silent Corner and the Empty Stage (1974)

In Camera (1974)

Nadir’s Big Chance (1975)

Over (1977)

The Future Now (1978)

pH7 (1979)

A Black Box (1980)

Sitting Targets (1981)

Enter K (1982)

Patience (1983)

Loops and Reels (1983)

Skin (1986)

And Close As This (1986)

In A Foreign Town (1988)

Out of Water (1990)

The Fall of the House of Usher (1991/1999)

Fireships (1992)

The Noise (1993)

Roaring Forties (1994)

X My Heart (1996)

Everyone You Hold (1997)

This (1998)

None of the Above (2000)

What, Now? (2001)

Clutch (2002)

Incoherence (2004)

Singularity (2006)

Thin Air (2009)

Consequences (2012)

…all that might have been… (2014)

From The Trees (2017)

In Translation (2021)

Live albums

Collaborations

Compilations

Miscellany

Introduction

In 1988 Peter Hammill played a concert at the Gardner Centre, the arts centre on the campus of Sussex University where I was a student. At the time, I hadn’t heard a note of his music, but was attracted by his vaguely Gothic-sounding surname (Hammer horror?), although not sufficiently so as to actually buy a ticket for the concert. Strangely drawn to the event, though, I found myself loitering disconsolately in the foyer of the Gardner Centre that evening, half-hearing the music coming from the auditorium, wishing I was inside.

Suffering no such hesitation on the occasion of Hammill’s next visit to the Gardner Centre two years later, I duly secured tickets for my then-girlfriend and me. I was impressed, but what really sealed the deal for me was another concert the following summer. By that time, having left Brighton and lost the girl, I found myself in Bristol and gravitated towards a fine record shop called Revolver. Chatting to the people behind the counter, they informed me that Hammill was playing that week in his home town of Bath. I took the train there and saw him play a magnificent show in a tiny upstairs venue called The Loft. Accompanied by violinist Stuart Gordon and saxophonist David Jackson, it was this immensely powerful concert that made me a Hammill fan for life.

The strange thing about this journey of discovery was that I made it without being aware of Hammill’s past with Van der Graaf Generator, my introduction to whom came later. For this reason, Hammill has, for me, always been a solo artist first and foremost, and the leader of VdGG second, with his solo albums and performances being those that capture the essence of what makes him great for me. It’s also the case that, unlike many hardcore Hammill fans, my favourite of those albums are the angsty, riffy records he made in the late 1970s and early 1980s (roughly speaking, the run from 1977’s Over through to 1983’s Patience). This has remained true even since VdGG reformed in 2005, as exciting as that reunion has proven to be.

Hammill is by some distance the most important musical figure in my life, the one to whom I’ve turned over and over again through the past thirty years, the only artist who embodies everything that I find thrilling and true about music. What, then, have I learned over these thirty years? That Hammill’s lifelong preoccupations – reason, memory, the unravelling of time and the choices we make – are deep, troubling ones. That there is something primal and atavistic about the way he confronts them in song. And that fifty years after he began, his music remains as visionary and essential as ever.

Although Hammill is a gracious and talkative interviewee, I have only rarely quoted his words on specific albums or songs given in interviews over the years. I have, however, quoted extensively from the ‘artist’s notes’ that he wrote about some albums on his website; from the sleeve notes to the albums that were remastered and reissued on Virgin in 2006-2007; and from the Sofa Sound newsletters and journal entries, also on his website, where he writes detailed notes on each new album as it is released.

An index to this book can be downloaded from my website viennesewaltz.net.

Fool’s Mate (1971)

Personnel:Peter Hammill: vocals, acoustic guitar, pianoGuy Evans: drums, percussionMartin Pottinger: drumsHugh Banton: piano, organRod Clements: bass, violinNic Potter: bassRay Jackson: harp, mandolinDavid Jackson: saxophones, fluteRobert Fripp: electric guitarPaul Whitehead: tam-tamAll songs by Peter Hammill, except where notedRecorded at Trident Studios, London, April 1971Produced by John AnthonyUK release date: July 1971Cover: Paul Whitehead

Hammill’s début solo album is an anomaly – a collection of short songs recorded over four days in 1971, but mostly written years earlier. The album was recorded in the midst of a feverish blast of VdGG activity, with the H to He, Who Am The Only One album having been released just a few months prior, and the group’s masterpiece Pawn Hearts soon to follow.

With the group gigging relentlessly in the UK and western Europe for virtually the whole of 1971, it must have been something of a relief for Hammill to retreat to Trident Studios, with a trusted cadre of musicians gathered around him, to finally realise a cache of songs that had been living inside his head for several years. As Hammill told an interviewer at the time: ‘I just feel that they are a part of me still, and that in a way they are something that I have to exorcise.’

Nevertheless, Fool’s Mate is very far from being a work of juvenilia. Like favourite children, one or two of the songs have remained as staples of Hammill’s live sets throughout his performing career. Others, tuneful and optimistic, bear the unmistakable traces of the late 1960s environment in which they were birthed – that brief moment when psychedelic pop was beginning to evolve into underground rock. Here and there, too, we find elements of the savage intensity that was to characterise Hammill’s entire approach to songcraft, tenderness laced with anguish and turbulence.

Musicians on the album included Hammill’s VdGG bandmates Banton, Evans, Jackson and Potter, lending a baleful VdGG influence to several tracks on the album. Also on board were Ray Jackson and Rod Clements from Charisma labelmates Lindisfarne, not to mention Robert Fripp of King Crimson on electric guitar, who was known to Hammill having played on H to He,Who Am The Only One. Together they give the album a quirky, diverse sound that renders it unlike anything else in Hammill’s back catalogue.

The title Fool’s Mate refers to the quickest possible checkmate in the game of chess. As a long-time chess aficionado (cf. the title of VdGG’s Pawn Hearts, the back cover of Chameleon in the Shadow of the Night and the photograph on the inner gatefold of 1985’s The Margin), Hammill is attentive to the beauty and difficulty of this game, to say nothing of the way in which victory is achieved through the gradual attrition of one’s opponent’s options, a progressive besieging leading to annihilation. In its knotty complexity and its troubling entanglement of situations, Hammill’s music approximates to the reality of chess. We see the earliest traces of that here.

‘Imperial Zeppelin’ (Hammill, Smith)

One of two tracks on Fool’s Mate with lyrics by Hammill’s VdGG co-founder Chris Judge Smith, ‘Imperial Zeppelin’ is a barnstorming opener to the album. Gleefully proposing a Utopian existence above the Earth, the song imagines piling on board the eponymous airship to ‘have love a mile above’, while the Earth seethes with hate below. The occupants of the craft plan to throw the seeds of love overboard, a notion that, Hammill acknowledges in a note in his first book of lyrics Killers, Angels, Refugees, ‘as a romantic fiction, remains appealing.’ Jackson lets rip on sax around Evans’ formidable drumming while Fripp adds fractured lead guitar to the organ-led middle section.

‘Candle’

Written as early as 1966, this funereal song is powered by grim acoustic riffing from Hammill and by Ray Jackson’s spiralling mandolin work. The lyric is a trifle overcooked, but Hammill’s voice convincingly conveys a sense of raw abjection. John Anthony’s production situates Hammill’s wounded vocals in a hazy middle ground, as if on the verge of being extinguished. ‘For the life I was part of breathes its last, and not only life but hope has gone away,’ mourns Hammill, while Jackson’s delicate mandolin propels the song gradually upward.

‘Happy’

Banton, Evans, Jackson and Potter are all present and correct here, but despite this, ‘Happy’ is probably the least VdGG-like song in Hammill’s catalogue. A light and relatively trivial exercise in romantic affirmation, this is the kind of song Hammill probably had to write, but by the time he came to record it had already left well behind. David Jackson’s flute threads its way elegantly through the song, while Hugh Banton’s vigorous organ work lends the song an air of authority I’m not sure it deserves.

‘Solitude’

One of the album’s key tracks, ‘Solitude’, is a devastating piece of work, showing an extraordinary level of maturity considering that Hammill was not yet twenty when he wrote it. This is true even when you take into account that the first and last verses are based on the poem ‘Feldeinsamkeit’ (‘Alone in Fields’) by the German poet Hermann Allmers, which probably came to Hammill’s attention due to its setting by the composer Brahms. Drawing on Allmers’ Wordsworthian notion of Romantic solitude, Hammill finds himself ‘far from grime, far from rushing people’ and retreats into ‘a tiny peace’ from which he is able to sense ‘the lovely white clouds glide across the sky.’ Hammill’s guitar work is remarkable, with splintering notes and grinding chord progressions adding to the sense of extreme willed solipsism that hangs blackly over the song. His vocals, meanwhile, catch a note of intense regret that detonates at key moments during the song. Most strikingly, Ray Jackson lends the song a warped folk-blues sensibility with his weaving harmonica lines, stalking the piece in restless counterpoint to Hammill’s urgent acoustic riffing.

‘Vision’

One of Hammill’s most enduring and best-loved songs, ‘Vision’ has long been a staple of his live performances. It’s not hard to see why, since it is at once simple, heartfelt and shimmeringly beautiful, with Hammill’s devotional voice rising like shafts of moonlight above Banton’s gorgeous piano. Hammill has never sounded more enraptured than he does here, never more dazzled by the pain and breath of love. ‘Vision’ is a sublime appeal to transcendence, a love song fully entitled to take its place among the greatest love songs ever written.

‘Re-awakening’

Another song on which Hammill is backed by the other members of VdGG, ‘Re-awakening’ is an arresting, energetic workout that seems to stand at that pivotal moment where late ’60s optimism was shading into the darker, more uncertain times of the early ’70s. Finding that ‘re-awakening isn’t easy when you’re tired’, Hammill proposes as a response to ‘curl up, slide away and dream your life out.’ If that sounds like the polar opposite of Timothy Leary’s famous exhortation to ‘turn on, tune in, drop out’, it’s a conclusion that’s hard to resist in the face of Hammill’s commanding vocal performance, not to mention Jackson’s astringent blasts of sax and Banton’s luminous organ work.

‘Sunshine’

‘Sunshine’ is an interesting footnote in the VdGG story, being one of two tracks on the group’s first demo tape, which ultimately led to them being signed by Mercury Records in 1968. That embryonic version, which survives, was cut by the first line-up of the group. The version on Fool’s Mate, as you might expect, is considerably more polished, with David Jackson parping away happily on saxophone and Robert Fripp contributing whacked-out lead guitar. The song itself is bouncy and euphoric, unlike anything else Hammill has ever written and reminiscent of early Bowie in its goofy cheerfulness. Yet with the curious reference to ‘E-S/M attractions’ in the lyric alongside sentiments like ‘I’m ready to be led’, ‘How sweet it would be to be chained by your side’ and ‘for you I’d get hooked and float six inches mud-free’, one can’t help wondering if there’s something more going on here than meets the eye.

‘Child’

Even when accompanied only by himself on guitar, Hammill has never been any kind of folk singer. Eschewing the cyclical force and repetition of traditional music, he works with dramatic chordal voicings that fragment and bleed into one another. ‘Child’ is a fine early example, a dreamlike ballad that sees Hammill’s languorous vocal floating hazily over vapour trails of acoustic guitar. David Jackson’s tender flute and Robert Fripp’s miraculous electric guitar add to the flickering nocturnal ambience of this beautiful song.

‘Summer Song (in the Autumn)’

Out of the five or six tracks on Fool’s Mate that feature the other members of VdGG, most of them don’t actually sound like VdGG songs. ‘Summer Song (in the Autumn’) is the exception, an imposing cut that makes a powerful impression despite being the shortest song on the album. Although Jackson is absent, the song is possessed by the collective consciousness of the group, with Hammill’s uncannily pure alto reaching for the sky amid Banton’s magisterial organ and Evans’ hugely impressive drumming. Hammill adds seething piano stabs to this bleak tale of depression and suicide, rounding out the song’s grim portrayal of a mind on the brink of collapse.

‘Viking’ (Hammill, Smith)

Chris Judge Smith, co-founder of VdGG, penned the text of this historical curio. Like Smith’s other lyrical contribution to the album, ‘Imperial Zeppelin’, the song forsakes Hammill’s imagistic force and psychological acuity in favour of a queasily drawn imaginary scenario. Drawing on the 13th century Icelandic Vinland sagas, the song depicts a crew of longshipmen returning home from their long explorations. Hammill’s vocal is oddly inert, none more so than when he recites a list of various Vikings. Ray Jackson’s harmonica and Fripp’s lead guitar add much-needed colour, but aren’t enough to lift the song above the mundane.

‘The Birds’

Another song that Hammill has returned to frequently in live performance. As with ‘Vision’, its longevity is not hard to understand, for this is a song haunted by sadness and loss, its emotional impact undiminished by the years. Hammill evokes a world without pity, where the passage of the seasons is thrown into disarray and where the pain of lost love is reflected in unforgiving coldness and death. Hammill’s deeply affecting vocal traces its way through Banton’s rapturous piano, while Evans lays down intricate fills and Fripp takes a radiant solo.

‘I Once Wrote Some Poems’

The album ends on another high note with one of Hammill’s strongest early songs, a wracked solo confessional that would not have sounded out of place on his later masterpiece Over. In barely two minutes, Hammill’s vocal progresses from an agitated whisper to a spectral calm and finally to a barely controlled rage, accompanied by weighty chords and angry slashes of guitar. Savagely intoning that ‘I never wrote poems when I bit my knuckles and Death started slipping into my mouth’, the commitment and intensity of Hammill’s performance leave you thunderstruck.

Bonus tracks

The 2005 reissue adds five bonus tracks, namely demo versions of ‘Re-awakening’, ‘Summer Song (in the Autumn)’, ‘The Birds’, ‘Sunshine’ and ‘Happy’.

Chameleon in the Shadow of the Night (1973)

Personnel:Peter Hammill: vocals, guitar, piano, Mellotron, harmoniumGuy Evans: drums, percussionDavid Jackson: alto and tenor saxophones, fluteHugh Banton: organNic Potter: bassAll songs by Peter HammillRecorded at Sofa Sound, Sussex and Rockfield Studios, Monmouth, February and March 1973Produced by John AnthonyUK release date: 4 May 1973Cover: Paul Whitehead

If Fool’s Mate was essentially a retrospective collection of songs written while Hammill’s career was still in its embryonic stages, Chameleon in the Shadow of the Night represents a dramatic step forward, a definitive statement of where he stood at the time as a singer, songwriter and musician. A mix of introspective solo acoustic numbers, dynamic rockers and one genuine prog epic, the album incorporates a range of approaches that were to recur throughout Hammill’s career.

Like many of Hammill’s early solo records, the gestation of Chameleon is inextricably linked to the story of Van der Graaf Generator. The songs that would go to make up the album were mostly written in 1971-72, during a time of tumultuous change for the group. The touring commitments that had seen them travel hectically across Europe throughout 1971 continued well into 1972, as they carried out heavy promotional duties for the Pawn Hearts album which had been released in October 1971. By August of 1972, however, they had split – ‘blown apart,’ in Hammill’s words, ‘by the intensity of the work.’

Chameleon contains at least one song, ‘German Overalls’, written in direct response to the boredom and stress of that constant touring. What is more, ‘(In The) Black Room’ had been written for the group and had been played by them in the final throes of touring before the split. Since the other members of the group all play on the album, it’s clear how closely related the two entities ‘Hammill’ and ‘VdGG’ were at this point – as, indeed, they were right up to VdGG’s reformation in 1975.

The other reason why Chameleon was an important album for Hammill lies in the manner of its recording. Believing, not unreasonably, that he would not always have the benefit of record company patronage, Hammill decided to seize control of the means of production. He bought a four-track TEAC tape recorder, installed it in his home in the Sussex village of Worth, and set to work. The solo acoustic parts were all laid down on the TEAC, which may account for the low-fidelity sound quality of much of the album. Crucially, however, home recording was a method that would serve Hammill well in the years to come, protecting him to some extent from the vicissitudes of the commercial record industry.

The group parts, meanwhile, were recorded at Rockfield Studios in Wales with VdGG’s regular producer John Anthony at the controls. When it came to choosing a set of musicians to flesh out the songs in the studio, there was only one option. Banton, Evans, Jackson and Potter were so perfectly attuned to Hammill’s creative visions that they were able to function equally as well as his backing group as they had as his VdGG bandmates. Together they made Hammill’s first true solo album, a record that stands both as a rich collection of songs and as a waypoint to his future direction.

‘German Overalls’

A strange yet wholly characteristic number to open the album. The curious title is a punning translation of ‘Deutschland über alles’, the first line of the German national anthem, which since the end of World War II is no longer sung. The song itself was inspired by a gruelling tour of West Germany, which VdGG undertook in May 1971, including stops at Mannheim and Kaiserslautern (referred to in the song as ‘K-town’, the nickname given to the city by US servicemen). The text grimly recounts the penury and fatigue that ultimately led to the break-up of the group, with an anguished vocal performance set to churning waves of acoustic guitar. Banton and Jackson have walk-on parts in the narrative, and Jackson also appears musically, his squally sax interventions lending weight to Hammill’s increasingly disturbed singing. The song is also notable for the first appearance of what Hammill describes in a sleeve note as a ‘junk shop harmonium’, its dread overtones framing the Gothic imagery of the ‘cathedrals spiral skywards’ section.

‘Slender Threads’

This is the first of three solo acoustic guitar songs on the album. The lyric tells a story of breaking up and drifting apart, of recrimination and regret, narrated in the soul-baring confessional style in which Hammill was by now excelling. Raking pitilessly over the embers of a failed relationship, the song anatomises how ‘we start out together, but the paths all divide’, ending with a chilling image of ‘the knife already turning in my hand.’ There’s nothing so comforting as a verse-chorus-verse structure here, and the words erupt like an affliction. His voice shifting between a sombre baritone and an eerie falsetto, Hammill sings with a strange English precision that intensifies the emotionally turbulent landscape that the song inhabits. His guitar, meanwhile, swoops and glides around the contours of the song, avoiding any hint of fulfilment or resolution.

‘Rock and Role’

One of the most sheerly enjoyable songs on the album, ‘Rock and Role’ is a key track in Hammill’s development as a musician. Throughout his career, Hammill has shown a love for three-chord power and simplicity that sets him well apart from most of the artists normally labelled as progressive rock. There’s a seam of raw energy running through his work that puts me in mind not only of the punk acts that were to follow but also of early ’70s fellow travellers like Hawkwind, an association later acknowledged by Hammill: ‘in terms of the noise, the rawness and energy level during their live performances [VdGG and Hawkwind] weren’t that far away. The anarchic element and the sonic quality and rawness of punk was there.’

This aspect of his muse effectively starts here, Hammill having recently acquired a new Fender Strat that he quickly put to use on ‘Rock and Role’. This cut fairly crackles with electricity, as Hammill’s chiming rhythm guitar swarms around Jackson’s majestic sax blowing, Potter’s rock-solid bass and Evans’ all-pervasive stickwork. The lyric is somewhat opaque, which hardly matters when the overall effect is as fresh and jubilant as this.

‘In the End’

Hammill’s piano playing is a remarkable thing, seen to full effect on ‘In The End’. Dense clusters of notes hang defiantly in the air, shapeshifting in time with the rugged landscapes of the text and occasionally resolving into momentary but achingly beautiful threads of melody. This song is a long, emotionally draining depiction of a mind hemmed in by lacerating self-doubt, drawn in unsparing textual detail. And when Hammill sings lines like ‘no more rushing around, no more travelling chess; I guess I’d better sit down, you know I do need the rest,’ you’re struck by the way the lyric explodes everyday utterances into blinding flashes of insight.

‘What’s It Worth?’

Like the earlier ‘Slender Threads’, this acoustic guitar song is played in an open D tuning, resulting in a slightly off-kilter sound that matches its wonky melody and baffling lyric. But it’s a sly and bewitching tune, with Jackson’s delightful flute darting like fireflies around Hammill’s compelling vocal performance.

‘Easy to Slip Away’

It’s back to the piano for this essential cut, one of Hammill’s greatest ever songs. On one level, it’s a sequel to the VdGG classic ‘Refugees’ (from 1970s The Least We Can Do Is Wave to Each Other), taking up the characters of Mike and Susie from the earlier song and lamenting the loss of close friendships with them. As is well known, the characters are real; Susie is the actress Susan Penhaligon and Mike is Mike McLean, both of whom shared a flat with Hammill in London in 1968. But the song transcends the merely autobiographical with its terror-struck realisation of the fleeting, evanescent nature of time. Hammill’s vocals reach new heights of intensity, his dark lamentations and shrieks of angry falsetto amplified by desperate hammerings on the piano. David Jackson is a vital presence throughout, clouds of fervent saxophone orbiting Hammill’s ever more bitter language. ‘Easy to Slip Away’ is a masterpiece, its harrowing insights impossible to unlearn or to forget.

‘Dropping the Torch’

This intimate, desolate song drifts by on softly intoned vocals and twilit flickers of acoustic guitar. The lyric draws upon threatening imagery of imprisonment: walls, chains, the crushing of freedom. As the song goes on, hope seems progressively extinguished until, finally, an uncomfortable conclusion is reached: ‘time ever moves more slowly; life gets more lonely and less real.’ The claustrophobic encroachment of the text is reflected in the song’s melancholic tone, with Hammill singing and playing as though trapped in some remote, airless cavern.

‘(In The) Black Room/The Tower’

The album’s one genuine prog epic, ‘(In The) Black Room’, had seen life as a VdGG song in concert during 1971-72, and was slated for inclusion on the next VdGG album after Pawn Hearts. The group’s demise in 1972 put paid to that, but a rough and ready rehearsal version survives on the 1981 Time Vaults compilation. The version on Chameleon, though, is the definitive one, with Banton, Evans and Jackson all present to summon the dark forces of VdGG. The piece is a frenzied interior journey of immense majesty; Hammill pushes his voice to its absolute limits, railing and burning in the throes of a soundworld rich in atmosphere and incident. Monstrous sax and organ riffs battle for supremacy against Evans’ hyperactive drumming and Hammill’s freewheeling piano runs, while the dynamic shifts that take place in the ‘Tower’ section ratchet up the tension still further. Lyrically, the song is a catalogue of typically Hammillesque oppositions: free will versus predestination, doubt against certainty, the rational and the speculative. References to the Tarot – the Priestess, the Star, the Fool and of course the Tower – heighten the sense of occult mystery that pervades the song, while the line about ‘going to the feelies’ is a reference to Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World, in which the feelies are a kind of cinema involving touch as well as sight and sound. Such arcana, however, are less important than the overall gripping impact of this extraordinary song.

Bonus tracks

‘Rain 3am’

A rare example here of a new, previously unreleased song being disinterred from the vaults. Originally released on the 1993 Virgin compilation The Calm (After The Storm), the song was recorded at Worth in 1972. It was not specifically intended for inclusion on Chameleon, but fits perfectly here as a bonus track, being very much of a piece with other solo acoustic guitar songs of the period. Jackson’s sensitive flute skips lightly through a filmic succession of nocturnal images, with a dying drunk and a lurking cat Hammill’s only company. The oppressive imagery and slashing guitar make for a highly effective mood piece.

The 2006 reissue also includes live versions of ‘Easy to Slip Away’ and ‘In the End’. Due to a lack of high-quality live recordings from the period, these are taken from a bootleg, Skeletons of Songs, recorded in Kansas City, USA, in 1978. This, however, is the best PH bootleg ever released, so the appearance of these two songs here is a definite bonus.

The Silent Corner and the Empty Stage (1974)

Personnel:Peter Hammill: vocals, guitar, piano, Mellotron, harmonium, bass guitar, oscillatorHugh Banton: organ, bass pedals, bass guitar, backing vocalsGuy Evans: drums, percussionDavid Jackson: alto, tenor and soprano saxophones, fluteRandy California: lead guitar on ‘Red Shift’All songs by Peter HammillRecorded at Sofa Sound, Sussex and Rockfield Studios, Monmouth, September and October 1973‘Red Shift’ recorded at Island Studios, London, April 1973Produced by John Anthony and Peter HammillUK release date: 8 February 1974Cover: Bettina Hohls

A 2014 poll held on an internet discussion group showed that The Silent Corner and the Empty Stage was by some distance the most popular of Hammill’s solo works among fans, while ‘A Louse Is Not A Home’, the epic with which the album concludes, was the most popular song. Clearly, therefore, we are dealing with a major work here, and indeed the album represents a considerable advance on Chameleon. The production is fuller, the arrangements more imaginative and the full band songs – recorded again with VdGG as the backing group – are easily the equal of anything VdGG had released up to that point.

By the autumn of 1973, Hammill’s home studio set-up had become more sophisticated, with further instruments, effects boxes and even an oscillator added to his armoury. As a result, the solo tracks recorded at Sofa Sound for Silent Corner – ‘Modern’, ‘Wilhelmina’ and ‘Rubicon’ – sound more fully realized than their counterparts on Chameleon had been, with ‘Modern’ in particular benefiting from a full panoply of studio effects.

The songs themselves had been written at various times over the preceding years, and were in some cases contemporaneous with material that had ended up on Chameleon. Indeed, ‘Red Shift’ and ‘Modern’ had originally been penned as far back as 1968 and 1969, respectively. Three albums into his solo career, Hammill was still working his way through a backlog of songs he had not yet recorded, sculpting and refining them into a body of work.

VdGG were still on hiatus, of course, but that didn’t stop Banton, Jackson and Evans from once again convening with Hammill at Rockfield to lay down the full band songs ‘The Lie’, ‘Forsaken Gardens’ and ‘A Louse Is Not A Home’ with John Anthony at the controls. ‘Louse’, like ‘(In the) Black Room’ before it, had been performed by VdGG during 1971-72 and had been intended for the next VdGG album. The odd man out was ‘Red Shift’, which had been recorded back in April 1973 at Island Studios in London and featured a scorching solo by Spirit guitarist Randy California. Taken as a whole, The Silent Corner and the Empty Stage is one of the great Hammill albums, an unruly masterpiece from beginning to end, essential listening for anyone with the slightest interest in ’70s progressive rock.

The cover was designed by Bettina Hohls, a German artist who had earlier lent her voice to a few songs by Ash Ra Tempel. The front and back covers were visually arresting, but the bizarre design on the inner gatefold was far from in keeping with the music. This was also the first Hammill album to feature his distinctive handwriting on the cover and inner sleeve.

‘Modern’

The album kicks off in uncompromising fashion with a dangerous voyage through mythical civilisations. This is the one that illustrates how far Hammill’s home studio set-up had developed since Chameleon. Recorded entirely at Sofa Sound, the song is a dense patchwork of sound that evokes the lost cities of Jericho, Babylon and Atlantis with ruthless stabs of guitar and frosty clouds of Mellotron. Hammill’s voice reaches peaks of declamatory fervour as he rages that ‘like the inmates of asylums, all the citizens are contagiously insane.’ In a long, ghostly middle section, skeins of acoustic guitar pick their way through desolate harmonium before a mighty riff descends into the final verse. Hammill still performs this song regularly in concert, a testament to its enduring visionary power.

‘Wilhelmina’

Hammill, not yet a parent himself, wrote this touching song for the daughter of VdGG drummer Guy Evans. An elegant piano melody glides through the song, making space for softly strummed acoustic guitar, spare touches of Mellotron and what sounds very much like a harpsichord. Hammill sings with deeply felt conviction and a rueful touch of misanthropy, warning that ‘people all turn to children, spiteful children, and they’re really so cruel.’ Many years later, a considerably less jaded Hammill would revisit similar themes on ‘Sleep Now’ from the album And Close As This, this time dedicated to his own young daughters.

‘The Lie (Bernini’s St. Theresa)’

This incandescently powerful song was inspired by Hammill’s time at Beaumont College in Old Windsor, a private school run by Jesuits. Interviewed about the song later, he described his religious education as ‘a great confusion of sex and religion… I was into it from the point of view of being in love with all the female saints.’ It’s hardly surprising, then, that the song also takes inspiration from the Ecstasy of St. Teresa, a sculpture by the Italian sculptor Bernini that can be found in the church of Santa Maria Della Vittoria in Rome. From the transported expression on St. Teresa’s face to her bare feet and parted gown, the sculpture is gloriously, transgressively erotic. Hammill sees ‘rapture divine, unconscious eyes, the open mouth, the wound of love’: a potent sexual charge refracted in the ice-cold marble of Bernini’s masterpiece. Meanwhile, the Lie of the title (described by Hammill in the same interview as ‘religion in the way that it is presented to you’) subsists in the angst-ridden vocal delivery and in the air of tortured melancholy that afflicts the song. Hugh Banton adds devotional organ to the ritualistic knell of Hammill’s piano.

‘Forsaken Gardens’

Here’s an intense, dynamic rocker with an addictive rhythmic drive and one of the most emotive lyrics Hammill ever committed to tape. One of the last songs to be written for the album, it has a tautness and economy which shows the direction in which Hammill’s songwriting was heading at this point, away from the baroque richness of songs like ‘(In the) Black Room’ and ‘A Louse Is Not A Home’ and towards a harder, leaner form of expression. This direction would ultimately lead to the barren forms of the first VdGG reunion album Godbluff, and indeed the reformed VdGG would occasionally play ‘Forsaken Gardens’ in concert (there’s a live version on the 2005 Godbluff reissue). The song begins as a rapt setting for piano and voice before Jackson and Evans enter around the two-minute mark and blast the song wide open. The saxophonist blows with breathtaking verve and authority; as with VdGG, his skill lies not in soloing but in playing in and around the voice and other instruments, sounding like he is everywhere at once. The song’s parting declaration that ‘there is so much sorrow in the world, there is so much emptiness and heartbreak and pain’ is one of the most upsetting moments in all of Hammill’s work.

‘Red Shift’

Hammill had studied Liberal Studies in Science at Manchester University, an interdisciplinary degree that aimed to give a broader education in scientific subjects, including sociological, economic, historical and philosophical aspects of science. It’s not hard to discern the traces of this education in a song like ‘Red Shift’, with its disruptive assertion that ‘the more that we know, the greater confusion grows.’ The song itself is something of an outlier; with its steady, unhurried pace and clever, restrained use of effects, it’s as Floydian as Hammill ever got. Jackson adds spaced-out sax to the mix, but the real star is Randy California, whose serpentine solo ushers in Hammill’s final, shattering realisation that ‘Red Shift is taking away my sanity … I’m a song in the depths of the galaxies.’

‘Rubicon’

A return to home recording, but (as in the case of ‘Modern’) things were getting more interesting here. Alongside acoustic guitar and voice, we hear the spacey hum of what Hammill described in the sleeve notes of the 2006 reissue as ‘a single oscillator, unattached to any kind of synth.’ There’s also some nice springy bass guitar played by Hammill himself. The song’s an unnervingly placid mood piece with an early iteration of a theme to which Hammill would later return on more than one occasion: ‘I am a character in the play; the words I slur are pre-ordained, we know them anyway.’ Beset by self-doubt and resignation, Hammill’s voice drifts unsteadily through the song as though on the verge of exhaustion.

‘A Louse Is Not A Home’

This monumental piece began life as a VdGG song, but it has rightly ended up as one of Hammill’s most celebrated solo recordings. It’s a nightmarish, edge-of-the-seat ride through the cracks of a consciousness that, near to breakdown, finds itself in a house in whose shadows ‘lurks the spectre of Despair’. As the song progresses, the consciousness suffers agonising visions of cracked mirrors, moving walls and a faceless watcher before coming to an appalled understanding that ‘nothing else exists except the room I’m sitting in.’ The Gothic horror of these images recalls VdGG’s ‘House With No Door’; equally, it anticipates Chris Judge Smith’s libretto for Hammill’s 1991 opera The Fall of the House of Usher, on which the pair had begun working in 1973. The piece unfolds as if in the middle of a tempest, with hellish ensemble passages colliding into eerily quiet hymnal sections. Unleashing wave after wave of vicious imagery into the void, Hammill seems afflicted by some curse, an impression only reinforced by the glee with which he alights on the thrilling melody of the ‘what is that but out of and into’ and ‘is it a sermon or a confession’ sections. The group are on fire, with Jackson’s malevolent sax coiling like tentacles around Banton’s sublime organ and Evans’ furious drumming.

Bonus tracks

The 2006 reissue includes live versions of three songs from the album. ‘The Lie’ is taken from the 1978 Skeletons of Songs bootleg, a real high-wire solo performance. ‘Rubicon’ and ‘Red Shift’, meanwhile, are taken from a 1974 Peel session, with Hammill accompanied by David Jackson on flute and sax, respectively.

In Camera (1974)

Personnel:Peter Hammill: vocals, guitar, piano, Mellotron, harmonium, bass guitar, synthesizerGuy Evans: drumsChris Judge Smith: backing vocals, percussionPaul Whitehead: percussionDavid Hentschel: ARP programmingAll songs by Peter HammillRecorded at Sofa Sound, Sussex and Trident Studios, London, December 1973–April 1974Produced by Peter HammillUK release date: July 1974Cover: Frank Sansom and Peter HammillPhotography: Mike van der Vord

By the turn of 1973, Hammill had already recorded and released one exceptional album that year and had another one in the can. This astonishing burst of creativity showed no signs of abating as he embarked on the set of recordings that would become In Camera. What sets this album apart from Chameleon and Silent Corner is that while those albums contained significant elements of band recording, In Camera was an almost entirely solo endeavour. VdGG had split up the previous year and, despite the appearance of Banton, Jackson and Evans on both Chameleon and Silent Corner, there didn’t seem to be any immediate prospect of the group reforming. As Hammill writes on his website, it was ‘time to get serious about solo recording.’

Hammill laid down the backing tracks – guitar, bass and piano – at Sofa Sound and then decamped to Trident to overdub vocals, synthesizer and Evans’ drums. The synthesizer, in particular, is worthy of note since this represents the first appearance of such an animal on a Hammill album (although Banton had used one on Pawn Hearts). 1973 had seen the release and global success of Pink Floyd’s The Dark Side of the Moon, which included the dramatic use of an EMS synth on the track ‘On The Run’. Nor can Hammill have been unaware of Tangerine Dream’s Phaedra, released to great acclaim in February 1974, not to mention Brian Eno’s use of the VCS3 synth on the first two Roxy Music albums. It’s not surprising, therefore, that Hammill chose to incorporate a synthesizer (albeit an ARP, not an EMS) into several songs on the album. The ARP was programmed at Trident by engineer David Hentschel, later to forge a successful partnership with Genesis as their producer.

At this point in his career, Hammill was still reaching back into his past and finding songs that he had not yet perfected. ‘Ferret & Featherbird’ had been written as far back as 1969, while ‘Tapeworm’ dated from 1971. Otherwise, the songs were written in the studio, a methodology that would serve Hammill well on later albums.

In his sleeve notes to the 2006 reissue, Hammill notes that ‘the stretch of style and subject matter on this CD is extreme.’ Certainly, there’s a wide range of approaches here, from the zesty riffage of ‘Tapeworm’ to the seething cauldron that is ‘Gog’, from the plaintive cry of ‘Again’ to the dense musique concrète of ‘Magog (in Bromine Chambers)’. Yet despite the variety of styles on offer, the overriding impression is one of introspection. The soundworld is arid and enclosed, a reflection of the album’s gestation as a purely solo project. Not an easy Hammill album by any means, but an important one nonetheless.

‘Ferret & Featherbird’

This opening track was, Hammill relates in his notes to the album on his website, ‘a late entrant to the lists … something approaching a ‘sweet’ song was needed to balance the other stuff.’ Indeed the vibe here is very different from the rest of the album, the song being a tender ballad that wistfully recalls how ‘distance came between us long ago’, only to conclude on the strangely hopeful note that ‘time and distance make a love secure.’ The song had been written as early as 1969, and an earlier version had been cut at the sessions for the début VdGG album The Aerosol Grey Machine