9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Blackbird Books Marvin Entholt

- Kategorie: Wissenschaft und neue Technologien

- Sprache: Englisch

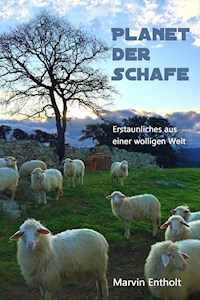

Sheep are perhaps the most underrated animals in the world. The unassuming ruminants have provided humans with food and clothing for ten thousand years. They have spurred the growth of entire societies and helped empires to rise. Could it be that these seemingly simple creatures have changed the course of world history? That without them, we would be living very different lives? What we can say for sure is that there are around one billion sheep on earth – in service of humans. To this day in many regions, they safeguard livelihoods and serve as an economic engine. Without these patient and undemanding animals, who knows how far we would have come? ‘Planet Sheep’ undertakes a journey into history, presence and future of the companionship of people and sheep.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

Inhaltsverzeichnis

About the author

Introduction

A world without sheep

The cradle of sheep and man

Of traders and robbers – in the highlands of Ethiopia

Bone work – archaeology with the cooking pot

Fat buttocks and double chins - the benefits of deviating from the beauty ideal

White gold - the discovery of the value of wool

Fleece versus fleece - wool in competition with synthetic textiles

The Golden Fleece - the sheep and its wool in mythology

Wooly enemies - the Highland Clearances

From prisoner escort to economic engine

Wooly prosperity - wool boom in Australia and New Zealand

The dance with the sheep - from wage earners and world champions

High Noon in the paddock - when friends are strangers

The last stage - of semi-nomads in Europe

The Choir of sheep – of poets and tenors

The sheep in sheep's clothing - when a mother loses her lamb

Vendetta and the Barracelli - blood feuds and night patrols in Sardinia

The sound of the mountains - the Campanacci of the bell makers of Tonara

Up to the alpine pastures and over glaciers - transhumance in Europe

Conquerors in sheep's clothing - of Vikings and other invaders

The Warrior - a fighter on the high seas

Are sheep stupid?

Leader Sheep - about sheepish leadership in Iceland

The Son of God - the sheep in art and religion

Shepherding hours - workshops for land longing people in Spain

Breast or leg - the nutritional value of ewe, lamb and mutton

Milk for the world - queuing at the ride

Off to Mecca - a ship's passage to doom

The stars of the scene – about the world of ram auctions

Dolly, the clone sheep – from a taboo to a forgotten anecdote

In vitro veritas - clone business and medicines from the udder

Oh Shrek - a truant and his heavy burden

The future is indoors - intensive sheep farming in China

Exhaust emission standard for sheep - in search of the emission-free ram

Moo instead of mow - the advance of the cattle

Salt on our fur - of extreme adaptability

No two sheep are alike - a brief history of the species

Quo vadis, ovis? - An outlook

Afterword

Acknowledgement

Final remark

Imprint

The German National Library lists this publication in the German National Bibliography; detailed bibliographic data is available on the internet at http://dnb.dnb.de.

© Marvin Entholt All rights reserved

Editing: Carlos Westerkamp

Typesetting: Jana Köbel Autorenservice

Cover design: Kirsten Breustedt

Cover photo: Marvin Entholt

Photographs in the book: Marvin Entholt, Kirsten Breustedt, Ragip Alkan, Johannes Straub

Blackbird Books Marvin Entholt Hedwigstr. 9 80636 Munich www.marvinentholt.com Instagram: planetsheep22

About the author

Marvin Entholt was born and raised in Bremen. He studied politics and philosophy at the LMU Munich and screenwriting and directing at the University of Television and Film Munich. Since then he has worked as a freelance documentary film author and director and as an author of screenplays, crime novels and non-fiction books. He lives in Munich and Berlin.

Introduction

For thousands of years, sheep and humans have formed a community. It is difficult to say who owes more to whom, but it seems reasonable to think that sheep get along better without humans than vice versa. Science proves it: Without sheep, mankind would not be where it is today. Since time immemorial, these frugal animals have been a storehouse on four legs and a supplier of warm clothing. Sheep have helped societies to grow, they facilitated the development of culture and, in many regions of the world, they are still his guarantor of life and work as an economic engine.

Sheep are one of the most underestimated animals in the world. Yet everything begins with it: domesticated wild animals form the very first herds of domestic animals became living productive resources. It is the beginning of livestock farming, a more significant step in human history than space travel or digitalisation: societies can now grow, clothe themselves, develop culture.

Since then, the sheep have patiently trotted after man on his conquests through the millennia. Could the Vikings have conquered the world without their woolen sails? Would Hannibal have crossed the Alps without mass-produced warm clothing for his soldiers? Would Florence ever have become a flourishing Renaissance metropolis without the

Medici, who owed their wealth to the wool and textile trade? Would the Industrial Revolution have happened without cloth that the weavers could weave? What would Australia and New Zealand look like today if sheep had not accompanied the first settlers on their ships?

Many people today are no longer aware of this ancient connection, but a more or less hidden affection for the wooly creatures still lives on in them. Hikers pause when they encounter a flock of sheep, and the two- and four-legged creatures curiously examine each other. This can go on for a long time, because sheep are not only curious, but also display their proverbial patience. Another characteristic attributed to them, stupidity, is not at all inherent in them. They are even cleverer than some of their two-legged contemporaries, but more on that later. So the wanderer looks back, and he too is filled with patient calm and joy at the unexpected encounter.

The affection for sheep probably stems from the awareness that has lain dormant in us for thousands of years that we owe nothing less than our own existence to the sheep. Without the fluffy four-legged friends, many civil achievements would never have existed, humanity would have developed differently and at a slower pace, our family trees would probably be scrawny plants with many bare branches, and our own might even be missing.

Why do parents like to bed their baby on a sheepskin? Because it is wooly warm and soft, of course. But perhaps also because there is an ancient connection between man and sheep, from the very beginning, in which there is a sense of security that sheep give us and which we still feel today. Those who approach sheep approach their own history.

A world without sheep

What would our planet look like if there were no sheep? People living in Central Europe in the 21st century would probably answer that here and there a few white spots were missing on the dyke or under the cypress trees in Tuscany, nothing more. That's true - on the one hand. But apart from the fact that the lowlanders do important work both under the trees and on the dykes, you have to look back a long way to get an accurate answer. Without the cloven-hoofed animals, our landscape would look completely different, on every continent. And probably even all of our lives.

Just as the sheep still keep the vegetation short in the Lüneburg Heath today, they do it everywhere - and always have. The animals are constantly on the lookout for food; a sheep will eat a few kilos of grass or other plants every day, if the vegetation allows it. While the animals roam the heath in search of food, they tear up thousands of small spider webs that would prevent bees from pollinating the flowers - a task that no one else would take on in the sheep's place. Herds led by shepherds have been part of this cultural landscape for so long that over time they have played a crucial role in this ecological system. They are part of its balance.

So we owe the sheep not only wool, milk and chops, but also honey. The animals probably don't care, because they are only interested in one thing during their forays: the best food. They prefer to eat tender tree saplings that stretch out between the heather. Without this landscaping work, the vast areas would become overgrown within a few years, and the unique heath landscape would turn into a completely normal forest.

Heidschnucken in the Lüneburg Heath

Sometimes in history, however, sheep have overdone it with landscape management. It is not for nothing that those in the British Isles who are less sympathetic to sheep say that nature has been "sheepwrecked" by the animals in many places.

The sheep are not the only ones who are well-disposed towards nature, which in many places has suffered "sheep breakage" as a result of the lowlands. However, it is of course not the fault of the individual sheep itself that it does not take human ideas of an ideal environment into account in its search for food. It is man himself who has devastated the landscapes over the centuries when he could not get enough of the wealth promised by the sudden boom in wool production. He simply sent more and more sheep to the pastures - until finally, in the truest sense of the word, no more grass grew, let alone anything else.

The islands of the Hebrides are a good example of how a landscape we admired for its rugged beauty was not always so barren. The brittle charm of the islands was created by man - or rather, under the millions of hoof-steps of his hungry sheep, it has become what it is today: a treeless landscape in which the wind whistling over the rocks does not even catch a bush because there is none.

One billion sheep populate the globe today, and there are over one thousand breeds of sheep in the world. The species has developed specialists for almost every land and climatic region. They are found on almost every continent, except in the Arctic and Antarctic. They can cope with almost any climate, they are frugal and will even chew on an old piece of wood if necessary. This makes them, together with their relatives the goats, the ideal livestock even in the barren and dry regions of this world. In times of climate change and increasing dryness and drought, this may prove to be even more important.

This could prove to be a decisive advantage over other livestock species. It is already clear that the carbon footprint of sheep and the amount of land they need to grow fodder make them the clear winner in a comparison with other livestock.

But is extensive farming in large herds still in keeping with the times? Isn't the itinerant shepherd an outdated model, a relic from days gone by that romantics rejoice in but that economists can only wearily wave off? Is a ten-thousand-year era coming to an end in a world where food production and sustainable energy generation for more and more people compete for limited land? Or will the sheep survive this economic and cultural change, just like all the great changes before it?

The cradle of sheep and man

Mesopotamia is considered the cradle of human culture. Coincidence or not: it is also the place of origin of the primeval sheep, the mouflon, from which all domestic sheep populating the earth today are descended. The large, horned animals still live in the mountains in the border region of Syria, Iran and Iraq. Ten thousand years ago, this common home of man and sheep became the place of origin of a unique success story.

It is the transition from the Pleistocene to the Holocene, our current earth age. The last ice age has just ended, Central Europe is being covered by ever-growing plants, and forests are springing up over large areas. People switch from hunting in the disappearing steppes to hunting game in the new forests, fishing is another source of food for the hunter-gatherer societies. At first, people discovered agriculture far away from Europe, probably at about the same time in China, South America, West Africa and the Levant - the area where sheep also began their career as domestic animals.

It is not known exactly how the first mouflon became domesticated, but there is a clear assumption: the hunters no longer kill all the animals, but take some of them alive.

At first, they only serve to be able to live off the success of the hunting trip for longer. But suddenly the human community realises that they have to feed the prey. After a few failed attempts, the initially tiresome task turns out to be solvable and, on top of that, rewarding, because the captured animals unexpectedly reveal an added value. Mother animals lamb, one animal becomes two all by itself, they bring people an animal return of one hundred percent and milk as a dividend. In the village communities, the realisation is spreading that this can be a worthwhile model for maintaining one's own basic supply without having to go on costly hunting expeditions with uncertain outcomes.

It was a revolution not only for the clan that first came up with the idea, but for all the people who followed them and adopted the model: From a few captured wild animals, first through natural reproduction, later through selective breeding, more and more specimens cavort in the improvised enclosures. This is the beginning of the domestication of wild mouflons. The animals are kept permanently close to human settlements. They allow a supply of food without the source of this food ever drying up: If reproduction works - and why shouldn't it? If reproduction works - and why shouldn't it? - an animal can be slaughtered from time to time without endangering the population, and milk production continues.

Humans become independent of the migratory behaviour of wild animals and hunting. At least from now on, hunting is no longer the only way to feed the community. The people, who can now also become settlers, win independence, security and freedom - admittedly at the price of the domesticated mouflon's freedom of movement.

At least their human keepers also make sure that the animals have enough to eat: a gain in comfort for the four- legged friends as well. At first, no one thought of cramming them into a stable.

It did not immediately occur to their owners that sheep could have a third use besides providing milk and meat. It took a few thousand years for man to realise that the fur of the animals could perhaps also be used for something and that the wool of the sheep was superior in many ways to the textile fibres that he had been using until then. It has significantly better insulating properties, both for heat and cold, it is more elastic than plant fibres, and it is easier to process.

Twill has been the most popular weave for fabrics since the Bronze Age. It has remained until the present day and can still be found in every pair of jeans. With the tools that people had at their disposal, spun wool could be easily processed into robust fabric. Wool also had another unbeatable advantage: it was much easier and more relaxed to obtain. All you had to do was watch the sheep grow its fur and shear it at some point. A simple work step replaced a long and laborious process to obtain the plant fibres that had been common until then: Ploughing, sowing, harvesting, processing - all this was no longer necessary, and unlike with arable farming, which depended on gracious weather, the yield was guaranteed.

Shahr-i-Sokhta in Iran is home to the oldest textile remains that archaeologists have so far been able to recover from their excavations worldwide. In the UNESCO World Heritage Site in the south-east of the country, the salt of the steppe has preserved even the finest organic materials that would have decomposed long ago under other conditions. They are about five thousand years old, and the fibres show yet another cultural innovation that went hand in hand with the harnessing of wool. The textile producers of the time quickly discovered another positive property of the material: Unlike plant fibres, it can be dyed relatively easily. Fashionable attributes and signs of class could thus be easily realised.

Textile archaeologists can derive a comprehensive analysis from an inconspicuous scrap of fabric: Dimensions, colour, fibres, fibre preparation and processing, weaving direction and thread count, edges and applied decorations, faults and wear and tear - every detail reveals something about the state of cultural development of the people who made and used the textile. A small remnant of wool can therefore tell us how people once lived - and in which direction they moved on in search of new lands and territories.

By this time, the sheep had long been established as a sustainable source of wool and milk. Knowing the value of his versatile companion, man thus sets out from Mesopo- tamia to other parts of the world, simultaneously heading east and west towards Africa and Europe - accompanied by ovis gmelini, the ancestors of all sheep, which will warm and feed humans for the next thousands of years, right up to our present day.

Dairy sheep in Sardinia

Of traders and robbers – in the highlands of Ethiopia

The sun is low and bathes everything in warm, soft light: freshly ploughed fields and fields where bright green grain is already halfway up. Behind them, slender, large eucalyptus trees with a strong wind blowing in their leaves. Sheep graze in their shade, watched over by a little girl. The young shepherdess wears a shiny green headscarf and an olive green jacket over her brown dress. She blends into the picture of countless natural tones as if she herself were part of this landscape.

The girl's name is Askale Selassie. She is ten years old and supervises her family's sheep on the outskirts of the village of Yecha in Ethiopia, two hundred and fifty kilometres northeast of the capital Addis Ababa. That sounds closer than it is. The distance means an eight-hour drive from the capital to the countryside, to a completely different, closed world. Only a minority of the villagers have ever seen the metropolis of Addis with their own eyes and not only on the screen, if the electricity supply works at all.

The village of Yecha is situated at an altitude of 3,400 metres, which is in no way apparent from the landscape.

The landscape is a vast high plateau with gentle hills and trees between agricultural fields. At a fleeting glance, you might think you are in the Rhön. The trees, however, are not beech or oak but eucalyptus groves, the land is moist and fertile due to the altitude and the clouds that regularly envelop everything in an impenetrable veil - at least in theory. But the climate and weather are incalculable. The altitude also brings the danger of frost, which can destroy an entire harvest and the farmers' hopes. Or the frost fails to materialise, but so does the rain, and instead of the cold, a drought deprives the farmers of their yield. Here, agriculture can only be one pillar of supply, and that is not particularly stable.

Askale Selassie's family keeps Menz sheep, a small, milk-coffee- brown, wooly subspecies named after the neighbouring region. The sixteen animals are the assets the family can and must count on. She also owns two cattle and a few chickens, but the sheep provide the day-to-day livelihood.

Sheep farmer in Molale, Ethiopia

If he breeds successfully, Askale's father Begashaw calculates, he can sell ten sheep every year and receive about forty euros per animal. With that, he can cover half the living expenses for his family of five for a whole year. One suspects that this cannot be a life of luxury, but it is all right the way it is, the father thinks. Still, he wishes for his daughter to do something different for once. He sends her to school, and the sheep make that possible for him, too. Begashaw says that the world is turning faster and smaller, and only those who have a good education will be able to survive in it. And so the days of Askale tending the sheep are probably numbered.

Until then, the girl carries a stack of plate-sized patties into the kitchen early every morning. It is fuel for the cooker, dried animal dung that burns excellently and is the common material for firing in the area.

Next to every farm in the village there are large piles of these slabs, neatly stacked up. Askale's mother uses them to fire the cooking place in the hut. The building is large and round, made of eucalyptus wood and carefully plastered, a stable house in which the chickens are now the only inhabitants in one corner, since there is a new living and sleeping room for the family next door.

The mother prepares Shiro for breakfast, a red bean sauce. As she does so, she admonishes Askale to devote herself to her English book, but as if on cue, a calf greedily prances into the kitchen and gives the girl the opportunity to devote herself to driving the cow's kind away instead of vocabulary. It is the weekend, the young shepherdess is spared the long journey to school today, and the whole strange world can be stolen from her if she can spend the day with the animals.

Since she was seven years old, Askale has tended the sheep alone, and should she ever leave the village, she will pass the shepherd's staff to her younger sister. It is always the children's job to herd the animals, especially when the parents have other things to do to support the family.

The father wants to drive two sheep to market, it is a good time to sell, soon the breeding season will begin.