23,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

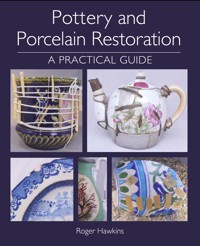

Pottery and Porcelain Restoration is a practical guide for amateurs to the craft of the professional restorer. With over 360 photographs, it explains the simplest, safest and ethical techniques that are recommended today and - essentially - do not further damage your pieces. Written with clear practical detail, it explains the full process and gives unique insight into the delicate job of the ceramic restorer. This new book introduces the history of pottery and porcelain, and gives an account of the methods and ethics of ceramic restoration; it gives a complete list and details of materials and equipment, and particularly advises on the best choice of glues; it describes the full restoration process, from preparation and cleaning to gluing and modelling, and finally to painting and gilding and provides step-by-step instructions for gluing multiple breaks, filling chips and large missing areas, as well as making lids, teapot spouts, hands, leaves, fingers and handles. Restoration examples are illustrated such as making Beswick horse legs, replacing missing handles on a Chinese jug and painting a Clarice Cliff jug and, finally, vital tricks of the trade are shared throughout and useful tips to setting up a workshop are given.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

Pottery andPorcelain Restoration

A PRACTICAL GUIDE

Antique English tile with transfer print of Jack and Jill c.1870.

Pottery andPorcelain Restoration

A PRACTICAL GUIDE

Roger Hawkins

First published in 2020 byThe Crowood Press LtdRamsbury, MarlboroughWiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2020

© Roger Hawkins 2020

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication DataA catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 676 0

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to all my past students who made my career even more enjoyable. To Alan Franklin who has put up with a constant barrage of questions. Geoff Crute and Dudley Thompson for reading the manuscript and their encouragement. Peter Tuckey for advice on photography. Thank you to Sonia for the cover picture. The teapot is on display in her fantastic shop ‘By Sonia’ in Brantome in the Dordogne. Last but not least, thanks to my wife Sally for her unwavering support, endless patience and hard work.

CONTENTS

Introduction

1 THE ORIGINS OF POTTERY AND PORCELAIN

2 THE HISTORY OF RESTORATION

3 TOOLS AND MATERIALS, HEALTH AND SAFETY

4 EXAMINATION AND CLEANING

5 DISMANTLING AND STRIPPING OLD REPAIRS

6 PUTTING IT ALL BACK TOGETHER

7 CLAMPS, CRACKS AND SPRINGING

8 ABOUT FILLERS, CHIPS AND FILLING GAPS

9 LARGE MISSING AREAS AND IMPRESSION MATERIALS

10 MOULDING AND MODELLING

11 PAINTING EQUIPMENT AND MATERIALS

12 PRINCIPLES OF PAINTING AND COLOUR MATCHING

13 AIRBRUSHING

14 GILDING AND GOLD FINISHES

Appendix: Setting up a Business

Glossary

Bibliography

Suppliers

Index

INTRODUCTION

In the world of professional porcelain conservation and restoration, ethical codes of practice exist that help protect our valuable possessions and heirlooms from being irreversibly damaged by thoughtless and clumsy repairs. Unfortunately, in the public domain, these ethics are not always understood or adhered to, and a ‘household repair’ can all too often prove disastrous to a valuable porcelain item or one where sentiment transcends any financial concerns.

Ceramic restoration has, over the years, always suffered from an image problem. Primarily because restorers have used inappropriate and inadequate materials, that were not specifically designed for use on ceramics. Most old restoration would eventually discolour, dry out and fall apart. Earlier repairs would be carried out using metal rivets or staples and various metal replacements because, at the time, suitable glues for ceramics had yet to be developed.

In recent years there have been many important advances in the development of adhesives, fillers and other materials specifically for the restoration and conservation industry. These have enabled the restorer to create a whole new range of techniques that have vastly improved the potential for acceptable and aesthetically pleasing results.

Mystery porcelain teapot found in Afghanistan.

We now have fillers and adhesives that do not discolour and are excellent for coloured translucent fillers on porcelain, reducing the need for over-painting. Glues are now available having the viscosity of water and non-yellowing. Although expensive, they far exceed the capabilities of the more traditional thicker epoxy resins.

Water-based acrylic paints have also greatly improved, enhancing their non-yellowing properties and making them safer to use.

There are now a bewildering number of glues available that the marketing people tell us are really ‘super’, and for many applications, these ‘instant’ superglues are very useful. They explain how their product is suitable for ceramics and almost everything else, but believe me superglue is the worst product ever to use for restoring pottery and porcelain.

As a tutor of restoration, I will advocate the use of the best materials available but also explain some of the worst.

The practical world of restoration and conservation moves at a much slower pace than the computer industry, but nevertheless, the resources we have available are frequently changing. Not only by the development of new products but by old tried and tested materials being taken off the market by the Health and Safety Executive. This has been most obvious over the past few years in the efforts to remove harmful solvents from various products.

No two restorers’ portfolios of equipment are ever the same. Despite our tuition, we all drift towards our own different ways of working. For example, many books mention pink sheets of moulding wax, which I find almost useless; I have found something much more practical. Whatever product I use in this book, you may very well prefer an alternative. It is important to experiment and keep abreast of the changes that new developments bring to the market. Do make sure however that any new products you use cause no harm to you or the ceramics.

It is important that all professional restorers use methods and materials that are reversible. The excessive and unnecessary over-painting by poorly trained restorers is always a cause for concern, but painting should be easy to reverse, without causing damage to an object’s surface. It is the preparation stages of cleaning, gluing, filling and modelling that often create untold damage that cannot be reversed. The potential for causing damage and disasters is endless.

This book will address these problems using the latest procedures professionally and ethically without the risk of wreaking havoc on treasured antiques.

Despite all the advances, better training and codes of ethics, porcelain restoration will still never be as acceptable as we would wish. There are, apart from poor materials, several reasons for this.

Once a ceramic item is damaged, the value plummets, even if it is only a crack that doesn’t affect the display.

The public seem very confused when I inform them that their soup tureen or teapot cannot be used in the normal way after restoration. There is still this very common myth that restorers can re-fire objects during restoration. Many people will not believe me when I say that it is not possible. This myth started in the 1960s and 1970s when some solvent-based paints had to be baked in an oven at 80°C for about thirty minutes. They became known as stoving enamels, and it doesn’t take much misuse of the English language to turn stove, bake or oven into ‘re-firing in kiln’. The myth still persists in some circles, not helped by some reference works on pottery and porcelain mentioning restoration and re-firing in the same sentence. The caveat to the above is that some experiments on restoration have been carried out at West Dean College using fired ceramic gap fillers. The process is highly specialized and would beprohibitively expensive for general restoration. Still in its infancy, it may have potential in some conservation situations (see Bibliography).

Furniture restorers have the luxury of being able to replace like with like. A fresh piece of veneer can easily replace a missing part and be coloured to match, using exactly the same timber as the original. A missing arm from a chair can be remade using the same wood. On a porcelain figure with a missing arm, I would have to use some type of plaster or resin material. Is it any wonder that professionally restored furniture usually retains its full value?

The public conception of restoration used to be based on the old adage of ‘make do and mend’. Now with changing fashions and increasing interest in antiques and their values, the public want their ceramics invisibly restored, just like furniture and oil paintings.

With the improvements in materials, conservation (or ‘museum restoration’ as some people call it) is slowly becoming more acceptable, and I have noticed a trend towards collecting old metal repairs and leaving them unaltered.

Invisible restoration will always have its place, but I fully endorse the ethical approach to the conservation treatment of ceramics and embrace their techniques in the following chapters.

A nineteenth-century Japanese Kutani vase with over-glaze enamel painting.

CHAPTER 1

THE ORIGINS OF POTTERY AND PORCELAIN

For the conservator and restorer, it is of profound importance to understand and recognize the differences between types of ceramic before any restoration procedures are carried out. We must begin with the origins and formation of clay and its mineral types. In the same way the successful potter must also have an extensive knowledge of his raw materials.

Planet earth has been with us for billions of years and in its various geological forms so has clay. From the very beginning, nature created one of the most useful materials on earth. It is readily available throughout the world and, in comparison to other minerals, the extraction costs are minimal. It has an enormous range of mineral ingredients that provide the potter with the versatility to transform natural materials into manmade objects that neither rot nor decay and can be made impervious to hot and cold liquids.

The earth’s surface is composed of different classes of rock types, granite being the most predominant. It is an amalgam of silicate minerals containing feldspar, quartz, mica and various metallic oxides.

Simple and basic pottery similar to this Turkish vase has been made for many hundreds of years.

Over millions of years, the continuous action of earthquakes and the immense temperatures from volcanoes and their gases slowly decomposes the granite surfaces. This is further exacerbated by the effects of heavy rain, changing temperatures, ice and frost. This gradual wearing down of granite mountains by the elements is called ‘weathering’.

Gravity eventually takes the decomposed particles down to ground level where they continue to slowly accumulate. Given the right geological conditions, this material of fine particles remains at the location where it is formed and over time can solidify into different types of softer rock.

As the granite and its feldspar content are subjected to the weathering process, the chemical structure of the feldspar changes so that this layer of soft rock transforms into kaolinite or its geological classification of hydrated aluminium silicate. Known by its common name of kaolin or china clay, it is the essential ingredient of porcelain.

It also has many industrial uses, including the production of gloss on paper surfaces.

The name kaolin derives from Kao Ling, a mountain above the village of Jingdezhen in China where the raw material was first discovered around 1,700 years ago. Because of the low iron oxide content, it is a natural white colour although containing a small percentage of other minerals. On average, it has 98 per cent purity and is referred to as primary clay – the perfect raw material for the early potters.

It is, of course, not the only type of clay used by potters. The other main category is secondary clay. Over many thousands of years some kaolinite deposits could be moved from their original locations by the continuing and irrevocable effects of weathering – the natural forces of wind, rain, ice, and rivers – moving the raw material to form new deposits, perhaps thousands of miles away.

Along the journey, the clay particles pick up other minerals, and organic matter and the constant grinding action by water reduces the individual particle size. All these added impurities change the molecular structure of the material and metallic oxides that create a varying range of colours, off-white, yellow, red, etc. This so-called secondary clay is no longer useful for porcelain but is used for practically everything else a potter may need.

These types of clays cannot however be just plucked from the ground and fired to produce a finished vessel. Clay of whatever type needs various additions to improve its suitability to meet all the potters’ criteria, the main one of which is for the clay to be malleable enough to work with and remain stable during firing. This is called ‘plasticity’.

The kaolinite mineral consists of microscopic flakes that move against each other, giving the clay extra plasticity. This makes it perfect for modelling as it can hold its shape better than other clays. Primary clay has a relatively large particle size, so its plasticity still needs improving. It also has an ordered and regular crystallized molecular structure which even after firing helps towards its translucency.

Postcard of Stoke-on-Trent Potteries.

A picture of saggers being stacked into a kiln. Staffordshire c.1900.

Secondary clay still contains kaolinite but, with all the impurities of various silicates and oxides, has a disordered crystallized structure and light does not penetrate through it. It does have a much smaller particle size giving greater plasticity, but may still need improving. Because of its formation, it comes in a vast range of chemical compositions and colours but nevertheless still needs additives. For example:

•Grog – a paste ground from previously fired clay

•Flint – ground to a powder

•Frit – a paste ground from glass, plus other minerals and metallic oxides to change the colour; can be added to the clay to alter its properties to suit the potter’s chosen product.

The percentages of ingredients have to be precise to obtain the right degree of plasticity the potter requires and also to match the requirements of the firing temperatures.

The clay then has to be prepared by kneading, wedging, sieving, etc. Apart from ensuring the ingredient minerals and oxides are thoroughly mixed and excess water removed, there must be no pockets of air bubbles in the clay as this would cause problems in the firing.

Modern clays are prepared by machine, but in the past, this was all done by hand in a very lengthy and laborious, yet hugely important process. The clays were then left for some time, weeks or months, to settle and ‘sour’. In fact, the Chinese potters left their clays to ‘sour’ for many years.

Firing and Kilns

Any glazed ceramics have to go through two basic kiln firings. The first, or ‘biscuit’, firing converts air-dried hard clay into a brittle but porous body. The second, or ‘glost’, firing fuses the glaze to the surface. The close chemical relationship between firing temperatures and the mineral content of the clay was not fully understood in the early years. The scientific analysis of materials was way beyond their knowledge. In firing ranges of up to 1,450°C, a miscalculation of 50°C could be ruinous for the kiln’s entire content.

Kiln designs throughout the fourteenth to the eighteenth centuries in the Orient and Europe were inefficient, dirty and dangerous. The sheer size of kilns needed to cope with the quantities of output could make the temperatures uncontrollable and uneven within the kiln. This could cause various faults in the finished wares.

Postcard of smoky potteries in Staffordshire.

During these developing and experimental years, the quantity of losses in the kilns was enormous, causing many small factories to fail. Thermometers using mercury were not invented until 1724 by Daniel Fahrenheit, but they could still not be used to high temperatures. It is a testament to the tenacity and skill of the early Chinese potters, that they produced vast amounts of high-quality porcelain. It was not surprising that the Chinese potters conducted religious ceremonies before each firing!

In the days before gas- and electric-powered kilns, coal was used as fuel. The inside of the kilns was full of soot and other airborne impurities. If the wares being fired weren’t protected, they would be spoilt in an atmosphere not conducive to making fine porcelain! Pieces being glazed had to be packed into the kiln very carefully so as not to touch anything else and provide protection against all the soot. One way of doing this was to place them in ‘saggers’, containers made of previously fired clay. Articles were stacked inside them, and separated by ‘spurs’ or ‘stilts’. Many nineteenth-century plates or large meat dishes can still be seen with stilt marks in the form of three small dots in a triangular formation. On expensive items, they would have been ground off (fettled) after firing. They are part of the manufacturing process and should never be considered as firing faults.

Many industries arising from the Industrial Revolution had the most appalling working conditions. Unsafe working environments and dangerous machinery were exacerbated by unscrupulous factory owners. By the nineteenth century, although kiln designs were much improved, the conditions had not. Children as young as five were working fourteen-hour days, often by the kilns in temperatures around 150°C. Needless to say, severe health problems were commonplace, and lead poisoning caused by the glaze ingredients was perhaps the most contentious. Throughout this period health concerns were of no interest and any safety regulations were non-existent. In Stoke-on-Trent with over 300 factories belching out black sulphur-laden smoke, life was not pleasant. Even iron gutters and downpipes suffered and didn’t last long.

In Jingdezhen, China, conditions were no different. In the sixteenth to eighteenth centuries, over 200 kilns were covering the sprawling village in black soot. It was a massive warren of alleys full of potters producing incredibly fine porcelains for the imperial court. The kilns could be 20 metres long and 20 metres high; they took days to fill with thousands of objects packed in saggers. In the Orient, wood was used as a fuel and two days of firing used 50 tons of wood and took a week to cool down. The famous bottle kilns in Staffordshire, although of a different design, could still take the same amount of time in the firing sequences.

Porcelain Ingredients

Describing the ingredients or recipes for early porcelain types is an almost academic impossibility. Apart from sparse historical records, the preparation of raw materials before the1800s was not exactly well-controlled and huge variants in batches of clay were commonplace.

The closest we can get to a definitive description of Oriental hard-paste porcelain is that it should consist only of kaolin and feldspar. Over the centuries, the Chinese have used all kinds of minerals and techniques to perfect their sought-after products. Accordingly, no two factories’ recipes were ever going to be identical.

Some sources state that the hard-paste porcelain is 50 per cent kaolin, 25 per cent feldspar and 25 per cent quartz, but in the early years of porcelain production in Jingdezhen, another main ingredient was mica. Mica is an unusual silicate mineral formed into thin, flexible layers of translucent sheets. Mica has a high melting point, so feldspar was added as a flux that would lower the melting temperatures during firing. When added to kaolin, this improved plasticity of the raw material and the translucency of the finished articles was greatly improved.

Bentonite, another useful clay mineral, was added as a flux and could improve plasticity, and also has a very high absorbency of water (hence its use in cat litter).

However, even without modern technology, we have ways of identifying various porcelain types, so this academic knowledge should not be lightly dismissed.

Firing Temperatures

So much is written about the mysteries of porcelain ingredients, that sometimes the importance of temperatures can be overlooked. For example, continental hard-paste generally has a lower first firing of around 1,000–1,200°C. After glazing the second firing is much higher at around 1,400–1,450°C. These high temperatures trigger the chemical changes that vitrify the glaze and body together; they become one, with no separation, therefore will not absorb water or staining, nor will the pieces become crazed.

English soft-paste porcelain with its different additives generally has a higher first firing of maybe 1,000–1,200°C but after glazing a lower second firing of 900–1,100°C. This fuses the glaze on top of the body; therefore, the absorption of moisture, crazing or staining become possible.

Primary Clays

Primary clays or porcelains have an average biscuit firing temperature of around 1,000°C. As the temperature in the kiln slowly rises to about 300–350°C any organic impurities are burnt away and any remaining water, albeit at a molecular level, will burn out a little later at around 500°C. As the heat rises to about 575°C, a fundamental change in the crystalline structure of the quartz in the clay body occurs. This change is called a quartz inversion. Maybe this is the point at which an object of natural clay becomes a man-made object.

As the temperature rises to about 800–900°C, any carbon or sulphur impurities will burn away, allowing an amalgam of silicas and minerals to melt and bond together in a process called vitrification. At these high temperatures, the vitrification of the molten minerals fusing together helps to fill the microscopic pores in the clay, increasing its strength. At 1,000°C, an unusual mineral called mullite begins to form into a needle-shaped crystallized structure that blends with the clay adding further strength to the finished articles.

Secondary Clays (Pottery and Earthenware)

The ingredients of secondary clays vary enormously, but the molecular changes during firing are similar to primary clays. The significant difference is in their firing temperatures. At the biscuit firing, the temperature is lower at about 750–1,000°C. Much above 1,100°C some secondary clays may deform and break down. Because the biscuit firing temperatures are not high enough, the mineral particles in the clay do not fuse together in the same way as primary clays, so any earthenware products will still be porous. A coating of glaze over the whole object or perhaps just inside a vessel will render the item impervious to liquids after a second firing.

Secondary stoneware clays contain ground flint, stone and various fluxes that help reduce the temperature for vitrification, so stoneware can be fired as high as 1,400°C. This can make it very tough and durable with a lower porosity than normal earthenware.

Glazes and Decoration

A list of techniques and ingredients used in glazing and colouring ceramics is, of course, an entire book’s worth of knowledge. Glaze is a layer of glass-like material covering a fired clay object to overcome porosity and provide a decorative surface. Glazes are formed primarily from silica with feldspar and various other minerals in differing proportions. Silica on its own has a melting point of around 1,700°C, so fluxes are needed that reduce the firing temperatures. Lead oxide was an important flux giving a wonderful translucence and good depth of colour, most notably on the nineteenth-century majolica wares of Minton and George Jones.

The harmful nature of lead is well documented, and borax was eventually introduced to replace lead oxides.

Metallic oxides provide ceramic colours – iron, copper, manganese and chromium gave the potter reds, greens, browns and yellows. In the early years of production, colours were limited by either knowledge or the technology available. The reaction between the oxides and minerals during firing was as usual very complex, and kiln temperatures were critical.

Without a doubt, the most important of all oxides was and still is, cobalt. Have you ever wondered why blue is the only colour always under-glaze and when any other colour is used it is always over the glaze?

The surface of biscuit-fired porcelain was decorated using ground cobalt oxides mixed in an oil medium. After having the glaze solution applied, the porcelain was fired up to maybe 1,400–1,450°C. Cobalt was the only oxide that could withstand the high temperatures without the designs being ruined. Instead of the oxides spoiling or defusing into the surrounding surface, the excessive heat created the perfect chemical reactions that turned the dull painting into the beautiful, rich cobalt blues against the white ground colours that were so sought after by kings and nobility.

Any other colours were applied over this glaze, but each colour had a separate lower firing because of the different way the oxides reacted to the heat.

This would obviously increase production costs, which explains why so much early porcelain is only under-glaze blue.

History of Porcelain Manufacturing

It is worth giving a brief history of porcelain development in Europe because it is as intriguing as it is important. The Chinese were producing porcelain as far back as the Han Dynasty (206–220ᴀᴅ). I am making the distinction between pottery and porcelain because pottery production goes back many thousands of years before. By the Tang Dynasty (618–907ᴀᴅ) highly-prized porcelain was being exported to the Islamic world and by the Ming period (1368–1644) blue and white, hard-paste porcelain was exported to Europe. The Chinese had taken centuries to evolve into the technical and artistic masters of a raw material yet to be discovered in the West. By the middle of the seventeenth century imports grew to vast quantities and hundreds of thousands of objects reached European ports.

The early merchants of the East India Company importing luxury items such as silks, tea and spices, encouraged the sales of porcelains. Apart from being very profitable, this was perfect ballast to stow in the lowest holds of the ship, so that the valuable cargo of tea, spices and silks could be stored above the porcelains away from any water and hungry rodents.

As the fashion for the exotic white, translucent porcelain became ever more appealing, so did the obsession for owning it, but no one in Europe or anywhere outside the Orient had any idea how it was made. The Chinese were naturally suspicious of foreign traders. Although world trade was well established by the end of the seventeenth century, China was still a very mysterious, secretive nation. They were very aware of how important the porcelain trade had become. To protect this hugely lucrative industry, the secrets of the manufacturing methods were closely guarded, and any attempts at espionage by European spies were easily thwarted. Foreign merchants and seamen were not allowed to leave the ports, and all business was confined to these areas. The porcelain producing area of Jingdezhen was over 700 miles from the nearest port of Canton (hence the term ‘Cantonese’). No foreigner was ever allowed to go there.

Political turmoil often causes problems in international trade, and when the Ming dynasty collapsed in the 1640s, the Dutch East India Company suddenly found they were without cargo. Their only choice was turning to Japan to satisfy the insatiable appetite for all things Oriental, and in doing so profoundly affected the porcelain trade. At first, the Japanese potters of the Arita area could not cope with the enormous increase in demand, but production was soon improved.

Blue and white under-glaze decoration was by now hugely popular, but the Japanese introduced two new styles; Kakiemon, a fine white body with red, green, blue and yellow over-glaze enamels, and the more influential ‘Imari’. (Imari was the port from where the Arita ware was exported), porcelain of under-glaze blue with over-glaze red enamel, often profusely gilded.

The Arita potters used almost pure kaolin and this, along with their firing techniques, enabled them to produce huge chargers and enormous vases and jardinières. These were made especially for export, and they took the West by storm. However, the Chinese, having recovered from their troubles, had by the 1700s re-organized their mighty porcelain industry and were back to their prodigious output. The Japanese industry fell into decline, but their new styles and manufacturing had set new precedents in the desirability of hard-paste porcelain.

THE NANKING CARGO

Not all cargos survived the long journey from Canton. Many ships were lost on the high seas, including the Geldermelsen that sunk in the South China Sea in 1752. After the discovery of the wreck, she became immortalized as the ‘Nanking Cargo’, as over 100,000 pieces of fine blue and white porcelain were auctioned at Christie’s in 1986.

Meissen

As the seventeenth century drew to a close, the obsession of collecting Oriental porcelain was reaching absurd proportions. The craze was undoubtedly led by Augustus II, Elector of Saxony from 1694 and King of Poland from 1697. Apart from continually needing gold to finance his disastrous military campaigns, he was spending vast sums of money on his porcelain collection.

Johann Fredrick Böttger was born in Germany in 1682, and by the age of twenty, he had become a talented chemist. Like his scientific peers, he still believed in alchemy (transmutation of base metals into gold). In 1701 his nefarious activities got him imprisoned by Augustus and, supplied a laboratory, he was ordered to produce gold. Obviously, gold was not forthcoming so Böttger slowly began to realize that discovering the formula for making porcelain might be his way to freedom. Though working in appalling conditions, after only a year, Böttger developed a hard red stoneware finer than any hitherto produced.

Despite the setbacks, Böttger’s perseverance prevailed and, by 1708, he had realized that local kaolin was the best material to use but had failed to recognize feldspar and quartz. He knew that high temperatures were essential to fuse kaolin but didn’t realize that feldspar acted as a flux to lower the temperatures and fill the kaolin pores that resulted in the translucent quality so desired. Instead, he used alabaster, a type of gypsum (calcium sulphate) and, against all the odds, finally produced translucent, white porcelain. It was, however, not commercially viable because alabaster melts at very precise temperatures and the kilns were unreliable and difficult to control.

Most books state that Oriental-style hard-paste porcelain was invented at Meissen in c.1710. I often wonder how true this actually is, because as Janet Gleeson says in her excellent book The Arcanum, Böttger used alabaster to produce Meissen’s porcelain, and although a miraculous achievement, it was not the true Chinese hard-paste recipe. The discovery of needing feldspar was not made at Meissen until 1724 by which time Böttger had died (1719).

Porcelain mania had now reached such bizarre heights that, in 1717, Augustus negotiated a deal to buy an important collection of Oriental porcelain inherited by King Fredrick William of Prussia. In return for a total of 127 pieces of porcelain, Augustus gave the Prussian king 600 dragoon troops from his Saxon army.

Sèvres

In Chantilly, France, in 1715, a factory was producing soft-paste porcelain with inspiration coming from Japanese porcelains. By 1738, the porcelain-mad Louis XV became involved. Just as at Meissen, workers were severely restricted, and no other factory in France was allowed to make porcelain without permission.

The factory was moved into a new building at Sèvres in 1756 and, in 1759, King Louis bought out the remaining shareholders, thus creating the second important European factory owned, and controlled, by a royal patron suffering from porcelain mania. The new factory was still only producing soft-paste porcelain, which could be unstable during firing. By the 1760s the recipe for hard-paste porcelain became less secretive, and the search for kaolin in France began. In 1768 a source was discovered near Limoges. By 1772 hard-paste porcelain was being produced commercially. Soft paste was only gradually phased out by the century’s end because some wares could not be decorated on hard-paste.

Islam and Lustre

Islamic pottery production was very active from around the seventh to the seventeenth centuries and influenced later designs across Europe. Earthenware was the typical clay body used but, during the twelfth century, a radical development brought on a fundamental change. Finely ground quartz was added to white clay and crushed glaze. Together with the appropriate new firing temperatures, it turned into a pure white body that if thin enough gained a translucency. This stone-paste or, so-called fritware, increased the potters’ versatility of the techniques available and improved the economics of production. Although not true hard-paste porcelain, it was no coincidence that it tried to emulate the treasures from the Orient. Unlike porcelain, it can be very porous.

Lustre was a decorative method popularized in Syria and Kashan (Iran) in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. Various metallic oxides were applied and fired in a reduction kiln (this removes oxygen from the kiln’s atmosphere). It was a complicated and therefore a costly exercise but remained popular enough to reach Moorish Spain in the thirteenth to fifteenth centuries as Islam advanced north. By the late sixteenth century, lustre had fallen from fashion as interest graduated towards the ever-increasing amount of imports from the Orient.

Lustre was later revived in England by the Arts and Crafts movement of the late nineteenth century, led by William Morris and the potter William de Morgan, who was heavily influenced by Islamic and Iznik designs from sixteenth-century Turkey and Moorish Spain.

Tin-glaze

The main constituent of the earthenware body was marl, a sedimentary rock decomposed into a silt-like clay. The low-fired, buff-coloured ware has a thick white opaque covering created by adding oxide of tin to a lead glaze – hence the term tin-glaze. From around the 1630s, the Dutch artists copied the Oriental designs to imitate the expensive imports. The cobalt blue was further glazed to help give depth to the colour to resemble the porcelain as closely as possible.

A French tin-glaze ‘Quimper’ dish c.1890. Tin-glaze was not exclusive to Delft wares. The French, Italians and Spanish all had prolific outputs during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries with their own very individual styles.

Between the early seventeenth century and the end of the eighteenth century, Delft dominated the home markets. In fact, it was so successful, exports were worldwide and ironically, included China and Japan.

During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries Dutch workers set up successful potteries in London, Liverpool and Bristol.

By the early 1800s, technology improved and more durable, and much lighter materials, such as Wedgwood’s creamware and Worcester’s soft-paste porcelain tea-wares, started to play a hand in the fall from popularity of Delft tin-glaze earthenware.

Delft and tin-glaze earthenware suffer from an unfortunate manufacturing weakness. The buff coloured low-fired material was intrinsically weak, and the hard-white glaze easily chips off, leaving the characteristic multiple-chipped edges around the early wares. A reasonable analogy can be made with taking a digestive biscuit and covering it in white icing.

DELFT

The huge popularity of Delft created its own niche market and, between 1650 and 1850, it is estimated that over 800 million tin-glaze tiles were produced.

English Pottery

Up until the 1650s, there was no home-grown English pottery ‘Industry’ to speak of, just small workshops dotted around the country, producing utilitarian objects from locally sourced clays. Transportation in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries was still horse and cart, travelling over mud roads. The haulage of ceramics and heavy raw materials like clay had their obvious problems. Cornwall and the West Country had clay, but no coal and it was a long ride from London. This kept the embryonic industry to a fairly parochial level.

The Staffordshire area, however, had everything; an abundance of different clays, more accessible routes to London and, above all, coal. From the 1760s, the canal network began to expand and Josiah Wedgwood, who could see the potential for transportation, was a keen investor. In Staffordshire from around 1710 a white earthenware body was introduced in the making of salt-glaze, giving a more refined appearance to the finely moulded shapes of bowls, jugs, teapots, etc. Some figures were produced but in limited quantity. Thomas Whielden started the production, in 1750 to 1800, of moulded earthenware shapes in bright lead glazes. Ralph Wood was from a potting family spanning 1715-1801, was also making brightly coloured wares in semi-translucent glazes.

A familiar type of Staffordshire figure marked Walton c.1820 with the common supporting ‘Bocage’ tree.

In 1759 Josiah Wedgwood started production. He was probably England’s first entrepreneur, perfectionist and pioneer in manufacturing. By the 1740s creamware, a medium-fired earthenware, was gaining popularity but, by the late 1760s, Wedgwood had introduced his own ‘Queen’s ware’. By the 1800s salt-glaze had all but disappeared. In 1760 the black basalt wares appeared and, in 1774, jasperware entered the world stage.

Other factories were not lying idle; this was, after all, the age of the Industrial Revolution. Ironstone was developed circa 1813 by Mason’s and had remained a successful ware up to the 1880s. By the 1800s fashionable ornaments were now reaching the aspiring middle classes in the guise of small, colourful and cheaply produced Staffordshire figures, often with ‘bocage’ (trees) acting as a firing support for the figures. Later in the century came the much-loved Staffordshire spaniels and flat back figures sometimes referred to as chimney ornaments. They were produced in hundreds of thousands and must have provided employment for many Staffordshire potters.

The continental ceramic industry had a massive fundamental difference over their English counterparts: royal patronage and ownership. Egos and corruption did not, however, make the difference any more advantageous. Through the seventeenth to nineteenth centuries, many English factories were successful commercial enterprises. The royals and members of the court would not lower themselves to deal in trade and be seen talking to merchants. This attitude is manifested in the lack of flamboyance of the English manufacturers, rather than any lack of enthusiasm, in their imaginative and profitable output.

Research and development were always at a frantic pace, but the search for porcelain material had to be kept within commercial and economic boundaries. From the late 1740s Bow, Chelsea, Bristol, Lowestoft, Derby and Worcester were all producing similar types of porcelain. Chelsea was the first porcelain factory to aim its market at the wealthy and directly copied Meissen originals in the 1750s. These weren’t to the Oriental recipe but did contain a primary clay and ground glass (frit) and maybe quantities of lime, sand, flint, etc. In the 1750s the ingredients and percentages were constantly changing as were the important firing temperatures. Most of the products were small and decorative useful items as the soft-paste still had a tendency to sag and warp during firing.

William Cookworthy of Plymouth discovered fine white kaolin clay in Cornwall in 1768 and after much experimenting obtained a patent for its use. Together with china stone (partly decomposed feldspar), the first English hard-paste porcelain was made. In 1780 the factory became known as New Hall and became quite successful.

Bone China

The constant need for improvements in technology was hastened by the continuing threat of competition from Oriental porcelain and the rising French and German factories. Among these many innovative and continuing developments of the eighteenth century, there were two that changed the English ceramic industry in a very profound and lasting way.

The first was the introduction of bone china, which is a porcelain paste with the addition of up to 50 per cent of bone ash, a calcium phosphate material made from incinerated animal bone. The resulting white powder improved the porcelain body by increasing its whiteness and translucency. Its greater plasticity enabled the potter to create much thinner and finer shapes needed for the ever-increasing demand for tea wares. The improved strength and chip resistance were achieved despite the lower firing temperatures of around 1,200°C, but above all, bone china was stain resistant.

Josiah Spode of Stoke-on-Trent was, by 1790s, manufacturing a soft-paste body with bone ash called Stoke China. By 1797 this was re-named bone china and became a huge success. Up until this time, the oriental porcelain tea-wares were the only vessels ideal for accepting the hot liquids without fear of cracking or staining.

The first recorded advertisement for tea in England was 30 September 1658. Samuel Pepys recorded in his diary on 25 September 1660 that he had his first cup of tea.

Tea soon became increasingly fashionable and, by the 1750s, had become well established in high society. It fitted well with the status-conscious aristocrats and the ladies of the house who could show off their imported Oriental teapots, cups and expensive tea leaves.

During this period, the English ceramic industry was still struggling with porcelain pastes. The middle classes, who could not afford Chinese porcelain, had to make do with salt-glaze and earthenware. The early soft-paste was an improvement, but in the early 1750s, Worcester added soapstone (steatite, a metamorphic rock mined in Cornwall) to the clay paste. This improved its ability to handle hot liquids and did not stain the white porcelain so easily.

The cost of these new porcelains and the stain resistance of bone china were much cheaper than imports, so the fashion of tea drinking became more affordable and widespread. This was a huge boost for the industry, and they were soon outproducing their continental rivals who had less interest in tea, preferring coffee and chocolate. By the early 1800s, the home and export markets for tea-wares, -caddies and -trays, etc., were massive and probably still is. Its importance continued throughout the nineteenth century as an ideal slip-casting material used for figures and other wares.

Transfer Printing

The second important English invention that changed the industry was transfer printing. Its effect was underestimated because it was introduced over a longer period, and didn’t have the cachet of hand-painted landscapes and botanical subjects.

A monochrome transfer print typical of the period. Signed by the engraver Thomas Toft, who was known to be working in Staffordshire during the late 1830s and 1840s.

John Sadler, a Liverpool engraver, is credited with inventing the process of printing on ceramics from 1756. A copper plate was engraved with a picture by cutting in lines or series of dots. The finished engraving was then coated in a black pigment. After rubbing away the excess, the remaining pigment was left in the engraved recesses. A special ‘tissue paper, made from hemp’ (because of the long fibres) was placed over the copper plate and put under a press. The tissue paper, when pulled off the plate could then be placed over the glazed object and rubbed on, leaving the pigmented design on the surface. After leaving for a few days to dry, it could then be lightly fired.

By the 1800s under-glaze transfer printing had become the ‘quantum leap’ the industry needed to boost its economic output. Above all, there was no competition from foreign rivals, their royal patrons showing little interest in cheaply produced printed wares. As one might expect, the first designs in blue and white were strongly influenced by the Orient. As production costs became cheaper, less affluent customers preferred English rustic and domestic scenes. By the 1820s with the addition of over-glazed colours of reds, yellows and green, humorous designs and topical events, such as new bridges or railways, etc., became popular subjects.

Coloured Printing

By 1848 an important improvement was made in being able to print all the colours under-glaze in one firing. The manufacturing cost benefits were enormous. The company responsible for its development was F and R Pratt and Company of Staffordshire who used three or four copperplate engravings, each one for a separate colour. Each tissue paper ‘pull’ was placed over the unglazed object and gentle pressure rubbing applied to transfer the pigment to the surface and allowed to dry. The remaining ‘pulls’ were placed directly onto the previous transfer one by one. Each transfer was lined up by two discreet dots at nine and three o’clock on the edge of the original engraving. When dried, the earthenware objects were glazed and then fired, causing all the colours to fuse together in the kiln.

Attribution

Hard-paste porcelain is a twentieth-century term used to describe Oriental and continental porcelain because of the higher firing temperatures used, resulting in a harder material.

Soft-paste porcelain now refers in general to English porcelains that have a softer finish because of the lower firing temperatures used.

Just to confuse the issue the early French and English factories used both hard- and soft-pastes but only for a short while.

It is vital to understand the differences in clay bodies because:

1.Restoration processes can change according to the type of body. For instance, some glues used on hard-paste porcelain would not work on earthenware as some wares are more absorbent than others.

2.The cleaning procedures depend very much on whether certain types of ceramic can absorb water or solvents.

3.From what it was made, when, where, and by whom, is essential knowledge. Your customers will seek your advice. You should be able to give it.

Sold on eBay as Chinese vases but are, in fact, French. Made by Edme Samson c.1890.

A perfect example of problematical attributions are the works of Edme Samson. The Paris factory opened in 1845 and began making copies of Oriental imports and Meissen, Chelsea and Derby figures, etc. His production of cheaper imitations was actually quite good quality, and his factory had a prolific output. Samson copies of Oriental mugs and plates are very convincing and easily fool the novice. Copies of Chelsea and Derby figures are still common, but unfortunately, Samson used the marks of the original factories, so one can argue that they are forgeries rather than mere copies. However, Chelsea and Derby used soft-paste porcelain. Samson used only hard-paste. If you cannot tell the difference, you may advise a customer towards expensive restoration on something with only a tenth of its supposed value.

Continental Hard-Paste Porcelain

In general terms, continental hard-paste porcelain has a very even, unblemished glazed surface. It will be greyish white in colour and this grey tone, surprisingly, seems to remain relatively constant throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. There is never any crazing or staining because of the vitrification of the glaze with the body. Rust stains, for example, caused by metal mounts remain on the glaze and can be polished out. By holding an object up to the light, it should be translucent enough to see your hand the other side. Anything hollow, say a vase or teapot, can have a torch put inside to show any translucency.

Oriental Hard-Paste Porcelain

Some of the earlier blue and white porcelains can have even glazes without too many surface blemishes. The body colours are always a lot greyer than continental. Most Cantonese porcelain is riddled with glaze imperfections such as pitting, black and brown specks and various lumps and bumps. Much is hidden by the designs of over-glaze enamels. The glazes can be very grey with greenish tones. Imari and Arita porcelains are also quite grey and with blemishes. The blue is under the glaze, the reds and other colours will be over the glaze.

Any translucency will depend on the thickness of the pottery.

English Soft-Paste Porcelain

The different firing temperature of English soft-paste helps distinguish its characteristics. The glaze sits on top of the body as no vitrification takes place. This allows the surface to remain porous, leaving soft paste susceptible to moisture absorption, therefore staining and discolouration. The glaze is also liable to suffer from crazing, and this is often in a small and tight configuration. The underside of soft-paste figures, if glazed, will often be patchy with pooled areas. Glaze blemishes are common. The colour of soft-paste bodies are much whiter than their continental and Oriental cousins and have a ‘creamier’ tone, and ‘warm’ feel to them. Like all porcelain pastes, you should notice a translucency against the light.

Bone China

Bone china, being a type of hard-paste, will have some of the characteristics, but will be a lot whiter and more finely potted and lighter. Royal Doulton figurines are a perfect example of bone china.

Earthenware, Stoneware, etc.

There are of course thousands of different types of clay bodies too numerous to mention here. The overriding fact is that held up to the light these secondary clay objects will be 100 per cent opaque. Surface blemishes, firing faults and staining are common.

Style

I have spent over thirty years precisely matching the colours of ‘white’ porcelains and can tell at a glance the origin of many, but the colour is not the only clue. Each country has its own stylistic nuances, and these are evident in its porcelain products. Style is not only the result of grandiose demands of royal patronage but the limitations of technology and materials available. The typical ‘Meissen’ hard-paste candelabra, if made in English soft-paste, would probably collapse, in the kiln. Many continental figures are larger than their English counterparts because soft-paste could not withstand the harsher firing temperatures required of hard-paste and would sag or distort during firing.

The ‘bocage’ (tree) seen on many English figures was an ingenious design used as a support to stop the figures sagging during firing. Chairs are often used within a design for the same purpose.

The scientific analysis of porcelain bodies to establish the percentage of individual ingredients is purely academic. The fact that a figure may contain 14 per cent or 45 per cent feldspar or bone ash does not really matter to us when handling porcelain. We are looking not at the invisible ingredients of the body but a glazed surface. What does matter is the ‘feel’, the colour, shape, design and style.

Identification of ceramic type can be a daunting challenge, but the more you handle, the quicker you will learn. Apart from the body colour I mentioned, look at the style and colour used in the decoration.

A hard-paste porcelain Newhall mug, easily confused with Chinese porcelain.

Study eighteenth-century Chinese porcelain painting and compare a coloured Newhall ‘chinoiserie’ design, or Lowestoft blue and white Chinese pattern with a similar Oriental piece. Although to a novice they may be identical, with familiarity you will soon recognize the many differences in their execution. Look in particular at the faces on English porcelains. Also note differences in the palette of colours and picture composition between English, continental and Oriental porcelains.

The same advice can also apply to other ceramics. The attribution of English and Dutch Delft can be extremely difficult. It’s just a matter of familiarizing oneself with the stylistic differences.

I am of course talking here about the early years of porcelain production where only a tiny amount bore any factory marks. Unlike these, the later twentieth-century wares of Doulton, Beswick, Moorcroft, etc., are very well marked and hold less fascination and confusion for the ceramic detective.

Common Ceramic Types

A large, early twentieth-century Italian Montopoli pottery vase with different textures and glazes.

Earthenware and Pottery

These names do not apply to any specific recipe but have become generic terms for any fired clay object. However, in general terms a secondary clay is used with additions such as other clays, ground stone or flint, grog, sand, etc., to give an enormous range of possibilities for the potter. Firing temperatures are a lot lower than porcelains. Any higher and the items would sag or distort.

Stoneware

Secondary clay with high proportions of ground flint or stone and highly fired, making it non-porous. Very tough and hardwearing with low production costs. Huge amounts were manufactured before the development of other materials.

A well-designed, relief-moulded stoneware jug by Charles Meigh. The design was registered in September 1844.

Salt-Glaze Stoneware

Salt-glaze stoneware is so called because of the unique way in which the glazed surface is achieved. During the biscuit firing of about 1,200°C, ordinary salt is thrown into the kiln at the highest temperature where the salt vaporizes onto the surface of any unglazed stoneware. This produces a very hard glaze, often leaving what is referred to as an orange-peel effect.

An unusual salt-glaze stoneware owl, showing the typical ‘orange-peel’ glaze of these wares.

This was an important technique for the potter, who had no need to incur the costs of extra firings to add glazes.

Parian

Copeland claimed the invention of this type of hard-paste porcelain c1845, a primary clay, with a high proportion of feldspar and frit, highly fired to about 1,400°C. It was usually unglazed, to keep down production costs, but sometimes glazed highlights were added. It was an ideal raw material for mass producing large good-quality, moulded figures. Because of the lack of glaze, the finished product often has a wonderful crisp appearance in the modelling.

An amusing Sèvres Parian figure. Note the clever use of a chair to act as a support during firing.

Majolica

Majolica has an ordinary earthenware body, but with a thick, vibrantly coloured lead glaze to which the term majolica actually refers. The flamboyant designs by Minton, Wedgwood and George Jones were very popular during the last half of the nineteenth century.

A Minton majolica teapot with typical vibrant glazes that were hugely fashionable in the later nineteenth century.

Jasper

Made famous by Wedgwood, jasperware has a stoneware body, coloured with copper manganese and other metallic oxides. It is very hard and has an unglazed matt surface. Some utilitarian vessels were glazed on the inside. The white relief decoration was separately moulded, and applied pieces of clay called sprigging. Some of the early jasperware was white stoneware but dipped into a blue-coloured slip.

Basalt

A black stoneware body, with a high proportion of ground ironstone, ball clay, Cornish clay and 10 per cent to 15 per cent manganese oxides to give the black colour. It was introduced by Wedgwood during the 1760s.

Wedgwood basalt vase with typical sprigging.

Terracotta

Terracotta means burnt or baked earth and now universally refers to the reddish-brown colour of flower pots and roof tiles. Although this red clay can occur naturally, the potter could still add oxides and minerals to improve its properties. Whitish, secondary clay perhaps coloured with yellow oxides could equally be called terracotta. They are low-fired (900°– 1,000°C), and some vessels may be glazed inside. Frostproof wares are fired to a higher temperature.

A nineteenth-century Staffordshire terracotta jug with a good moulded-relief design.

Ironstone

Ironstone was made famous by Mason’s c1813 and was very successful owing to its toughness and competitive pricing. It has an earthenware body with a high percentage of flint and feldspar.

Faience

Faience is the French term for tin-glazed earthenware. Typical wares made in Quimper (pronounced cam-pair).

Maiolica

Maiolica is the Italian term for tin-glazed earthenware, Cantagelli being a prominent name. Not to be confused with Majolica.

Identification by Broken Edges

As a restorer, you will have an enormous advantage over the casual observer in the frequent examination of broken shards. You can look in cross section at the body of the porcelain object ‘underneath’ the glaze. Always use a strong magnifying glass for your investigations.

If water is dropped onto a porcelain surface, it will run off, with no absorption. The opposite is true of a pottery surface.

Continental Hard-Paste Porcelain

These have a definite ‘silky gloss’ sheen to the broken edges. Notice how there is no distinctive separate layer of glaze on either surface because of vitrification. Just like the surface, the edges will be uniform in colour and texture and unlikely to show any blemishes.

Oriental Hard-Paste

Oriental hard-paste is very similar, but you will notice more imperfections in the body, such as tiny microscopic holes or black or brown specks (inclusions). These have been caused by poorly mixed additives in the original clay paste. Edges will always have a gloss surface which can vary from ‘silky’ to a ‘glass-like gloss’.

English Soft-Paste Porcelain

In cross-section English soft-paste porcelain is quite different from Oriental hard-paste. The edge surface will always be matt or dull and never glossy. It has a slightly coarser body than hard-paste. The body colour will be creamy white. There will be a clear distinction between the glaze layers and the body itself.

Edge of a hard-paste porcelain Chinese plate showing a typical gloss surface with no open pores or rough texture.

The edge of a soft-paste Worcester porcelain dish with a matt surface. A slightly rougher texture than hard-paste.

Satsuma pottery surface typical matt surface and rough texture with some open pores.

Earthenware, Stonewares and Tin-glaze

The lower the firing, the coarser and rougher the broken surface, always matt and sometimes showing articles of ground ingredients such as flint. Colours can range from dark red/browns to buff yellowish, grey whites. The broken shards of lower-fired wares usually have a very jagged edge with sharp peaks and troughs. Porcelains tend to have a cleaner and straighter line to the broken edge.

Tin-glaze pottery showing the usual biscuit-coloured body derived from Marl, and the white opaque glaze. Very coarse texture to the surface.

Poole pottery on a terracotta body displays all the character of tin-glaze, except it does not suffer from easily chipped edges because of a higher firing than most tin-glaze objects. No gloss and very few pores.

Newhall, English hard-paste, very slight sheen, some open pores.