Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: CompanionHouse Books

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

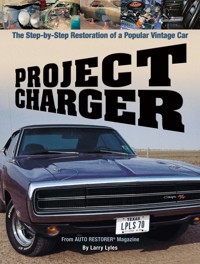

Join the restoration craze with the first automotive book from BowTie Press. This is a comprehensive, nuts and bolts approach to automotive restoration that will demonstrate the best way to bring a car back to its original brilliance. Restoration expert Larry Lyles makes the process come alive with over 200 color images and step-by-step details. While the vehicle being restored is a 1970 Dodge Charger, the techniques and ideas presented here can be employed to restore any vehicle. Originally conceived and written as a twenty-four article series for Auto Restorer magazine (the premier publication for die-hard restoration enthusiasts), this compilation delves into a complete, ground up restoration of a classic muscle car. It offers as much real-world information on how to accomplish such a restoration.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 391

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Karla Austin, Business Operations Manager

Jen Dorsey, Associate Editor

Michelle Martinez, Assistant Editor

Rebekah Bryant, Editorial Assistant

Erin Kuechenmeister, Production Editor

Ruth Strother, Editor-At-Large

Nick Clemente, Special Consultant

Vicky Vaughn, Book Designer

Copyright© 2004 by Larry Lyles

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of I-5 Press™, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in an acknowledged review.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Lyles, Larry.

Project Charger : the step-by-step restoration of a popular vintage car / Larry Lyles.

p. cm.

ISBN 1-931993-22-X (softcover : alk. paper)

eISBN 978-1-62008-015-3

1. Dodge Charger automobile—Conservation and restoration. I. Title.

TL215.D64L95 2004

629.28’722—dc22

2003022778

I-5 Press™

A Division of I-5 Publishing, LLC™

3 Burroughs

Irvine, California 92618

Printed and bound in Singapore

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Table of Contents

Acknowledgments

Introduction

1 Starting the Project

2 Teardown Begins

3 Glass Removal

4 Exterior Teardown

5 Moldings and Body Lines

6 Removing the Engine

7 Cowl Teardown

8 Reassembly Begins

9 Restoring the Trunk Floor Plan

10 Sheet Metal Repair

11 Refinishing the Underbody

12 Priming and Blocking

13 Refinishing the Exterior and Interior

14 Refinishing the Components

15 Powder Coating

16 Machine Work

17 Trim Work Begins

18 Window Tint and Door Glasses

19 Suspension Installation

20 Drive Line Installation

21 Front Sheet Metal

22 Bumpers, Decals, and Stripes

23 Interior Trim

24 A Look Back

Resources and Restoration Costs

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the many people who helped bring this project to life. To my wife, Pat, who understands the feeling of power and freedom a restored muscle car can bring, I say, “Thanks, here are the keys. Have fun.” To Bryan, who worked harder on this project than I could have ever expected, I say, “Thanks, here are the keys. Take it for a ride then get back to work.” To Ted Kade, editor of Auto Restorer magazine, I say, “Thanks, my friend. Here are the keys. Don’t come back until the fuel tank runs dry.” To everyone else who contributed so much toward the completion of this project I can only say, “Thanks. Wish you could be here to enjoy this car as much as we do.”

Introduction

I originally wrote a 24-article series for Auto Restorer magazine. My intent was to take readers through a complete ground up restoration of a classic muscle car while offering real world information on how to accomplish such a restoration. This book is a compilation of those articles.

As a seasoned veteran of automotive body repair and restoration, I’ve attempted to lead you through a complete restoration without getting you lost or confused in the process. I’ve purposely stayed away from the usual heavy doses of mechanical information found in many other publications and instead have concentrated on the more prevalent aspects of automotive restoration. I’ve tried to meet the mechanical needs for restoration and, where I felt the mechanical needs exceed the expertise of the average garage restorer, I’ve always suggested the reader seek the assistance of a professional.

You won’t find a lot of information on which part is correct for a particular year or model, nor will you find a tutorial on how to read VIN plates. What you will find is a comprehensive, nuts-and-bolts book on automotive restoration containing the best information available on how to bring your car back to its original shine and luster.

Although this book focuses on the restoration of a 1970 Dodge Charger, you can employ the techniques and ideas I present here to restore any vehicle. Selecting a Dodge Charger as our project vehicle was not mere happenstance. I have a long history with the Charger, starting with my first attempt at restoration dating back to my high school days in the late sixties. That car was a 1966 Dodge Charger. The car was wrecked at the time I purchased it at a cost of a mere $50. I took my first step into the world of automotive restoration and modification by shaving most of the chrome and adding a pearlescent Fire-thorn red paint job.

That beautiful car helped fund my next project, a 1970 Plum Crazy purple Charger R/T with all of the go-fast an 18-year-old should be allowed to own. After its untimely death due to a multiple car pile up, I took my father’s advice and turned my attention away from cars to concentrate on higher academic studies. My hope was to become something more than just another wrench jockey in a grease shop. Unfortunately—or perhaps thankfully—math and electronics bored me to death while bending metal and spraying paint, which I continued to do at a local body shop as I sought higher education, thrilled me. By the time I finished college, I realized cars were in my blood and I could do nothing to change that.

The art of body repair soon led me to restoring Ford Mustangs for a local Baptist minister in the days before having a restored Mustang was cool. That, in turn, led to restoring Corvettes and that led to custom work on vintage rods and old Harley-Davidson motorcycles. Intermixed with these classic automobiles and motorcycles came hundreds of broken and bent late models.

These days I no longer work on new cars. I can’t tell a Honda Accord from a Chevy Impala. Or does Toyota make the Impala? Anyway, I divide my time among writing books on automotive restoration, producing articles for Auto Restorer magazine, and restoring old cars like the Charger in this project.

Like many people you find at the local car shows who restore old cars, I returned the Charger to its former glory simply because I could personally relate to the car, not because the VIN tag identified it as something rare or something special. Most of those vehicles have already found residence in climate-controlled museums whose access is granted to only a chosen few. This car doesn’t have many of the desirable perks associated with owning a classic Mopar muscle car. There is no Six-Pack under the hood and no four on the floor. I chose to restore this car for one reason: It has my name on the title and it reminds me of days gone past.

My wife, who, by the way, owned a 1970 Dodge Super Bee 440 Six-Pack on the day I met her, is more excited about this restoration project than I am. I suppose that’s what automotive restoration is really all about: taking a long-abused old car, returning it to its glory, and seeing all those smiling faces and thumbs up as you cruise along the highway.

PHOTO 1: This is the interior from the passenger side. Notice the missing glove box and the hole where the radio was located.

CHAPTER ONE

Starting the Project

Ask any expert in the field of automotive restoration where you should begin a restoration project and chances are he’ll know the exact spot. Many restoration projects never get off the ground until someone points to a specific location on the vehicle and announces it is the place to begin. I can’t agree more. You have to start somewhere or the work never gets done. I just don’t agree that you should start your restoration project by working on the vehicle itself; you should start with documentation.

Oh sure, I could stand in front of any project vehicle, point to a location on the car, and pronounce it as the place you should start. You would cheerfully begin working on the vehicle, taking off parts, piling them here, and stacking them there. But within a short period of time the project would take on a life of it’s own. Expensive parts would suddenly be scattered here, boxes of nuts and bolts would grow up out of the floor there, and chrome trim and bucket seats would take up valuable space near the only work bench in the shop. New parts purchased six months ago, but not needed until next year, would strangely disappear; while old parts you will never need again would find places of permanent residence in the shop. The question of what to do next would become paramount in your mind. It doesn’t have to be like that. Restoring an old car ought to be fun. For me, it kept me out of my wife’s hair for quite some time.

The good news about restoring an old car is that any anointed place to begin is a good place to start. The bad news is the starting point is a long, long way from the ending point. A lot of tear down, repair, overhaul, replacement, and assembly must occur in the meantime. Unfortunately, all this “meantime” work can become daunting and sometimes downright depressing. A writer friend of mine once told me that all good books have a great first chapter and a blockbuster final paragraph. Everything that happens in between is just interesting filler designed to keep the reader turning pages. Restoring old cars is the same. The beginning is always filled with great promise, while the climatic end is something that can only be reached by turning every sweat-dripped and grease-smeared page in between. So where do we go from here?

Documentation

Step one in your restoration project should be documentation. By documentation, I don’t mean tracking down the history of the vehicle from the first oil change to the last tire rotation, or even from owner to owner or engine swap to engine swap. Having this information, however, does make the vehicle more valuable in the long run. Let’s face it—most of us are not trying to build a concours-grade vehicle worth millions of dollars, which translates into many millions of dollars spent in the process. What we are building is referred to as a driver, a dependable vehicle in which we can comfortably sport around town. Of course, having something everyone stares at doesn’t hurt either.

For this type of vehicle restoration, documentation means making several lists. You need a list for the new parts you have to purchase as well as separate lists for parts requiring overhauling, repairing, and refinishing. Having such lists allows you to determine where to begin your restoration project and how to systematically work your way through the process to a successful conclusion.

The first step in forming a list of new parts needed is to order catalogs. Every aftermarket parts supplier on the planet has a catalog. Some are dedicated parts suppliers, meaning they cater to one specific area of automotive restoration such as rubber weather stripping or suspension components. Others offer everything from lock knobs to hinge bushings. Some catalogs are free, but others are not. Of the ones that are not free, most will refund the cost of the catalog with your first purchase. Since most companies that charge for their catalogs offer extensive parts inventories, shelling out a few bucks to see what they stock is often worth the cost.

Next, go on-line. Many suppliers have excellent Web sites with products, prices, and helpful hints on how to use their products. Others have just enough Web presence to let you know they are out there. Reference the sites that look promising in a Favorites file (or Quick Reference file) for future use, or jot down the addresses on a note pad for safekeeping.

Finally, get input from your friends. I’ve never met a restoration buff who wasn’t happy to talk about his latest project, and I have never talked to one who didn’t leave me with more information than I had when we started talking.

Sources List

Armed with catalogs, Web sites, and friendly advice, you are ready to start building a file folder of your restoration lists and notes. Usually my file folder is filled with printouts from my computer. I open a word processing file on the computer and give it a project label; in this case I label the file Project Charger. In that file I make a sources list. This list includes every catalog I have along with the general contents (such as “Chrysler sheet metal source”) of each catalog. Next, I list the Web sites I like along with a brief content note on sites that contain information I may need. Last, I note the sources my friends offer plus the names of all the old car salvage yards in my area that still stock the types of vehicles I am working on.

The equivalent late model salvage yard is a different animal altogether. Late model salvage yards cater to the newer car market, which means they rarely stock any vehicle over 10 years old. They crush older vehicles to make room for the later models. Old car salvage yards keep cars until nothing is left but the rust. However, they, too, will eventually crush the remains of everything in the yard to make room for the newer old cars our grandchildren will want to restore.

The salvage yards I frequent identify the crusher candidates by painting a big X on the roof. Every time I make a trip to the salvage yard, I make sure the vehicles I am scavenging are not marked for crushing. If they are, I pick the carcasses clean of anything I might need before the crusher shows up.

Master Checklist

The next item in the file folder should be the master checklist. Compiling this list is a little more involved. I purchase a couple of loose-leaf notebooks, a package of ruled paper, and about one hundred pages of photo keepers. The photo keepers allow me to photographically record the entire restoration in chronological order, which helps when I’m ready to assemble the car again and serves to wow my friends once I’m done with the project. The packages of ruled paper let me write down every step of the restoration as I perform it, again to help during assembly of the car; and the notebooks give me a place to temporarily list broken, missing, or damaged parts before I forget about them. Of course, you may also choose to enter your master checklist information in a Word or Excel document. I find, however, that my low-tech method comes in handy when I am working in the shop because I don’t have to stop everything to clean up, go in the house, and turn on my computer. The choice is entirely up to you.

Photographs

After I identify and research my major rebuild issues, I document the original condition of the Charger with photographs. You will want photographs of everything about the car. For example, what decals or labels are on the car? Where are they located? How about those engine labels located under the hood; what do they say? Good close-up photography preserves this information. It is to your benefit to invest in a quality camera and film. Be sure the camera you are using takes clear close-ups, and have all of your photographs developed before you remove or alter the actual parts.

As I am photographing each and every part of the vehicle, I am also making entries in the master checklist. Later, when I look at my master checklist, I see that although the vehicle has rear bumper guards, it never had front bumper guards. Having this note reminds me I won’t need to add front bumper guards to my new parts list once I compile it.

Photographs also give me a visual reference to use when I’m rebuilding the car. For example, what was the original color of the brake booster on this car? A year from now when I start opening box after box looking for a brake booster and can’t find it, a quick look at photo 3 will tell me the car never had a brake booster in the first place.

Salvage Parts List

Armed with a plethora of photographs and page after page of notes and entries on my master checklist, it is time to put everything into some kind of order. First, I assemble a list of damaged or missing parts I may be able to locate at salvage yards. I make a copy of that list and take it with me every time I darken the gate to my favorite vintage car salvage yard. Having such a list means I don’t have to remember all those individual parts I need to locate for the car. Would you remember you need new defroster vents for the dash if you didn’t make a note of it? I wouldn’t.

New Parts List

Here, I list the new parts I need to purchase, a source for those parts, and the price of each part. One thing I learned a long time ago is when ordering new (aftermarket) parts from reputable companies, not all prices are created equal. That is why I keep so many source catalogs. Compiling a list of parts and sources allows me to build an order sheet for each source so I can make one large order instead of several small orders. The more money you spend in one place at one time, the more likely that source will offer you a discount. If not a discount, believe me, they will remember you the next time you place an order and treat you accordingly.

Overhaul List

I list everything in need of rebuilding in the overhaul list. You, or someone with the right equipment, can rebuild many old parts. The trick is to find the right parts to use when doing a rebuild. For example, door hinges are notorious for requiring overhaul. Alternators, starters, steering boxes, rear axles, and brake assemblies also come to mind. All of these parts can be overhauled but will require new parts and a little professional help in the doing.

Parts Needing Repair List

This is probably the easiest list to compile. If it is bent and you can repair it, add it to this list. If nothing else, it will give you a schedule to follow. Many of the parts will contain components that require overhaul, replacement, and/or refinishing. This list helps you keep track of the progress of the work on the other lists.

Refinishing List

Every part on your project vehicle is one color or another, whether that color is cast iron gray, Plum Crazy purple, or semigloss black enamel. I list each part that needs refinishing. Later, after it’s been painted, I will check it off. Does the part require priming? Is it best clear coated or will a single stage (enamel or lacquer) finish do? Is the part an interior piece or an exterior part? Having a refinishing list ensures every part gets painted before it is scheduled for installation back on the vehicle.

PHOTO 2: Begin compiling your restoration checklist from the ground up starting with the tires and suspension components. While these tires are badly worn, several new suspension components were found after looking under the vehicle.

PHOTO 3: This photograph was intended for referencing the color of the hood hinge, but it also helps me remember that the car doesn’t have a brake booster.

PHOTO 4: The interior of the vehicle is shot. Notice the missing driver’s door trim panel and the extremely worn driver’s seat cushion. Also notice the aftermarket steering wheel. This will go on the Salvage List because new, replacement steering wheels are almost impossible to find.

PHOTO 5: Having a photograph of the rear of the vehicle tells many stories about what the previous owner added to the car—in this case, rear bumper guards.

PHOTO 6: Yikes! Rust! At least this is repairable. I add a note to my overhaul list for future reference.

PHOTO 7: More rust! Where you find one spot of rust you will always find two spots of rust. This floor pan can be replaced with new metal. Again, I make a note on the overhaul list.

Initial Inspection

Armed with my checklist notebook and a good camera, the next step is the vehicle itself. Perhaps it is just ritualistic with me, but after purchasing a restoration project I walk around the vehicle and look it over. I may do this for a week or more before actually committing anything to paper or film. When I’m ready, I start taking notes. I write down everything about the vehicle. For example, I check for tire wear. Tires with odd wear patterns such as cupped areas or excessive wear on an inside tread can indicate a badly worn suspension. Next I look for damage on the vehicle. That includes everything from the wheels to the roof. I look for missing parts and parts I can see that I’ll need to replace.

Then I look at the interior. Primarily, I want to sit in the seat and observe what is in the interior. I want to know what works and what does not work. For example, I crank the engine and check the gauges. If they work, fine; if not, I make a note of the ones that do not. Do the interior lamps, switches, and clock work? Do the seat tracks work? You’d be surprised how many times I’ve tried to adjust a seat of a fresh restoration job only to find it wouldn’t move. This is something that you should take care of early in the restoration process, but something people often overlook in the haste of getting shiny new seat covers on the old ride.

As I check the car’s condition, I see the hood does not sit level with the fender. This is a telltale sign of a worn hinge. Should I place this hinge on the new parts list, the overhaul list, or is it a candidate for the salvage parts list? I place it on all three lists. Sometimes parts show up in the strangest places. But then you have to know you need the part to know you should buy the part.

This is also a good time to drop by your local automotive air conditioner repair facility and have the R-12 Freon drained from the air conditioner. During my initial inspection of the Charger, I found the A/C system already drained, but if yours is not, add it to the checklist.

Last, I ask a mechanic to go over the mechanical aspects of the car with me. I have already conceded an engine overhaul, transmission rebuild, and rear axle restoration. It is things like steering gear boxes, brake boosters, and HVAC units that have a way of sucking up dollars intended for use elsewhere on the vehicle. So be prepared for the worst. That is why you make a list and check it five or six times.

In the Charger’s case, I rate the overall condition of the car as good. Every exterior panel of the car is bent, but again, no panel needs to be completely replaced. I do find a little rust along the bottom of the right quarter panel, but I am unable to determine the extent of the rust on the floor to the quarter filler panel or the adjoining wheelhouse. It is important to note that the quarter panel and quarter filler panel are two different parts joined together at the floor. If the quarter panel had a rust hole in it you would be able to look through the hole and see the quarter filler panel behind it. To get a closer look at these areas, I will need to progress a little deeper into the restoration. I do find additional rust in the trunk floor pan area. This will require removal of the floor pan in that area and replacement with new sheet metal.

A quick look through an aftermarket parts catalog reveals that replacement floor pans for the trunk of this vehicle are readily available, as are the floor to quarter filler panels, should that become an issue. I note these problems as well as any other problems I encounter on the master checklist.

Parts Protection and Organization

As you get deeper into the restoration process, you will see that room to work diminishes as room taken for storage increases. It never fails that once you have a panel such as a door repaired, primed, and in need of storage, that part becomes a magnet for every loose object in the shop. The awful result is a nick, gouge, dent, or worse on the parts you thought you had already repaired. The next time you are in your local office supply store check out the plastic bubble wrap. It can be cheap protection for an expensive part.

I tag each part as it comes off the car. Small colored price tags—the ones with the handy string attached—are available at any office supply store. Use the tags to label parts as right or left, front or rear, along with the actual name, such as “back-up lamp housing.”

Keep similar parts together. By this I mean store all of the lamps from the rear of the vehicle in the same box and store all of the lamps from the front of the vehicle in another box. Don’t mix up the parts. This makes locating them later a less difficult task.

Final Thoughts Before We Go to Work

This is not the time to worry about how the hood, deck, or doors fit. These items have seen years of wear and tear. They are not supposed to fit and work like they did when they were new. As I go through the process of restoring the Charger, I will overhaul, replace, and rebuild all of these parts so they fit and work as they did when they were new. Over the course of the restoration, I will also completely reassemble the body of this vehicle at least once before final assembly to make sure everything fits as it should.

While the Charger is a total unibody vehicle, meaning the body cannot be removed from the frame, it restores pretty much the same as a framed vehicle. It still has front suspension components as well as rear suspension components to be dealt with. The basic difference is the body cannot simply be lifted off the frame to gain access to these parts. The parts are bolted directly to the unibody structure, and therefore require a little more close-quarters work when dealing with them.

There are, however, quirks inherent to the unibody that are not found on framed vehicles, and these differences must be addressed to properly restore the vehicle. I will discuss each of these factors as we encounter them.

PHOTO 1: Both doors on the Charger need to be realigned to fit before the car is raised on the jack stands. We use the alignment bar to tweak the doors into alignment.

CHAPTER TWO

Teardown Begins

The first step of actual hands-on work is to clean out the car. A lot of debris can accumulate in a 30-year-old car, and every bit of it needs to be removed to expose what lies underneath, that being the vehicle itself. I clean out the interior and the trunk area first, tossing out everything that’s not tied down or associated with the car itself. Note: If you happen onto the manufacturer’s vehicle build sheet (normally found under the back seat), which lists the build date, model, and every option that came on the vehicle; or if you find the owner’s manual or any other documents that might pertain to the history of the vehicle, keep them. They may come in handy later on.

Once I’ve cleaned out the vehicle, I take a walk around it looking for anything that might cause me bodily harm such as loose moldings, broken glass, dangling mirrors, or dangling windshield wipers. I remove all of these (even if they are in good condition), label them, and add them to the master checklist before I store them away. A damaged wheel-opening molding can be your worst enemy when it comes to causing bodily harm. This comes off and goes straight into the trashcan. Now I can work on the vehicle without worrying about being “bitten” by it.

Working Height

Ergonomics dictate obtaining a proper working height to prevent injury and fatigue. This is doubly true when working on an old car. The best way to reach a proper working height is to raise the vehicle using adjustable jack stands. This gets the car up off the floor and puts most of the working area high enough so you don’t have to stoop and bend to work on the car. A good working height is one where you can sit on the door scuff plate the same way you would sit in a comfortable chair, feet on the floor, knees slightly bent.

Before raising the car to working height, I adjust the doors. Most 30-year-old car doors sag, and since the Charger is a unibody vehicle I want both doors to fit as best they can. Using the door adjustment bar seen in photo 2, I tweak the doors to realign them. Note: You may find some door hinges so worn that you will not be able to adjust the doors to fit properly. In that case, adjust each door as much as possible before proceeding to the next step. You might try squirting a little WD-40 on the hinges and latch mechanism as well.

Any time a vehicle is elevated off the ground, each wheel should be supported to ensure proper weight distribution. At most repair shops, vehicles are raised using a drive-on lift, instead of the four points lifting system used when rotating tires, so the vehicle’s weight is distributed equally at all four corners, ensuring safety and vehicle stability. If you don’t have a drive-on lift, position a jack stand just inside each wheel to support the suspension and keep the vehicle stable.

For our purposes, however, positioning the jack stands inside each wheel won’t work because we will be removing the entire suspension system at some point, leaving nowhere to place the stands. Instead, let’s talk unitized body construction methods for a moment. All unitized body vehicles, including the Charger, begin life at four points on a building jig. These four points are the strongest and most balanced places on the car’s structure. That is why we will place the jack stands here. Illustration 1 is a generic model, but the principals of construction are the same for most unitized body vehicles. Each vehicle supporting point appears on the illustration as a symbol.

On the Charger, the boxed frame rails are welded directly to the floor pan. At the front of the vehicle, these boxed rails extend all the way to the core support, with the core support and the inner fender aprons welded directly to the rails. At the rear of the vehicle, the boxed rails begin just under the back seat, curve up and over the differential, and extend all the way to the rear body panel. The floor pan is welded to the boxed rails, as is the rear body panel.

ILLUSTRATION 1: This is a generic model, but it shows the basic principles of construction for most unitized body vehicles.

PHOTO 2: You never know what you will find when you clean out your project vehicle. Among all the clutter in the trunk we found a Cragar SS mag wheel, which is definitely a rare find.

PHOTO 3: All we really want is a little room to work. The Charger is raised approximately 18 inches off the floor (measured from rocker pinch weld to the floor) via the jack stands. The pads under the stands are made from 3/4 MDF (Medium Density Fiberboard). They eliminate the metal to concrete contact between the stands and the floor, reducing the chances of the Charger slipping off the stands.

Using similar principles, I can see how to suspend my Charger. For the front suspension, the Charger uses a bolt-on engine cradle, or K-frame, which also serves as the mounting points for the lower suspension arms. The upper control arms are bolted to the unitized structure of the vehicle.

The forward jack stand placement points can be found in an area directly underneath the cowl structure near the rear of the front boxed frame rails. Find the rear jack stand placement points in an area directly forward and inboard of the rear suspension mounting points (spring hangers), which are located on outer reinforcing box rails between the rear box rails and the rocker panel structure.

Once the jack stands are in place with the vehicle lifted off the floor, there is the problem of overhang. To get a better idea of exactly what overhang is, try opening a door on your project vehicle once you have it positioned atop the jack stands. You will find the doors hard to open and almost impossible to close. This is a direct result of overhang, which happens when the weight of the engine puts stress on the unitized structure of the body itself. Of course, at a later point in the restoration process, we will be removing the engine, thus eliminating the problem of overhang, but, for now, we need to contend with the problem.

Correcting overhang is as simple as placing a hydraulic jack under the engine cradle and applying just enough upward pressure with the jacking ram to take the engine weight off the vehicle structure. You know you have compensated for overhang when the doors once again open and shut like they should. That is why it’s important to adjust the doors before placing the car up on jack stands. We need a reference point to know when we have alleviated the overhang. Leave the jack in place under the engine. Note: I prefer to use a 4-ton portable jacking ram to hold up the engine and relieve overhang. Once the jack is in place and I’ve compensated for overhang, I remove the hose and pump from the jacking ram to reduce the clutter beneath the vehicle.

Now it’s time to remove the tires and wheels and begin work. Having the vehicle supported by jack stands is relatively safe compared to supporting the vehicle with a floor jack. However, let’s take one more step toward safety by sliding the tires and wheels back under the vehicle at each brake drum. Should the unthinkable happen and the vehicle slip off the jack stands, the wheels will be there to catch the vehicle before it mashes you flat.

Lose the Liquids

I start work on the vehicle by first disconnecting the battery and then draining the engine, transmission, and radiator of all fluids. Disconnecting the battery is for safety, while draining the fluids prevents messes all over the floor later on. The engine and radiator drain simply enough—I just loosen the drain plugs and allow the fluids to run into a catch pan.

The automatic transmission (standard transmissions need not be drained) has to be treated a little differently, as most transmissions don’t have drain plugs. I place a large catch pan under the transmission and begin loosening the pan bolts.

The transmission pan is the large, flat pan located on the bottom of the transmission, attached with 12 to 14 bolts. Loosen all of the bolts at least two full revolutions and then, if necessary, pry the pan loose from the transmission housing using a flat-bladed screwdriver. Be careful not to damage the pan or the housing with the screwdriver. Some fluid may seep from the upper edges of the loosened pan at this point. Continue loosening the pan bolts one at a time, working around the pan from corner to corner. The pan will slowly drop, allowing the fluid to pour into the catch pan. Continue loosening the pan bolts until the fluid stops pouring from the transmission. At that point, remove the pan and allow any fluid left in the transmission to drain into the catch pan.

When the fluid is drained, I reinstall the pan on the transmission to prevent contamination of the inner workings of the transmission. Then I dispose of these fluids properly. Most cities have an automotive fluid disposal depot that will take the old fluids off your hands for a nominal fee. Check with your local sanitation department for details on how automotive fluids should be disposed of in your area.

Check the Underbody

The next step is to take a droplight and go under the vehicle to look for problems. First I check the brake system for leaks. Brake fluid on the back of a brake drum, tire, or wheel indicates a leak at the brake cylinder. Note any leaks you find on the master checklist.

Next, I look at the shock absorbers. Generally, these are removed and replaced with new ones. If you have leaking shocks, check with the manufacturer about warranty. Many shock absorber manufacturers offer lifetime replacement warranties covering shocks that spring a leak. If your shocks aren’t leaking, toss them in a box for later comparison with the new ones.

PHOTO 4: The unitized structure of the Charger requires a bolt-on engine cradle, which also houses the lower front suspension control arms. The upper control arms mount to the unitized structure. Since all of these components must eventually be removed from the Charger, this would be a poor location to place the jack stands.

Notice how I add everything to the master checklist? There are several things to add to the checklist while under the vehicle, so be sure to include all of them. As I said at the beginning of this book, it really doesn’t matter where you start working on your project vehicle, as long as you start somewhere. Everything I have done up until now has been preliminary work designed to make things easier later on or to call attention to problems I may encounter as I get deeper into the restoration process.

Strip Interior

The real work begins with the interior. First, I take out the seats. After that, I remove the door trim and quarter trim. The garnish moldings go next, as well as the headliner, carpet, and seat belts. Be sure to tag the seat belts’ locations, even if you plan to replace them later. Believe me—sorting through a pile of seat belts trying to decide where each one goes can be a problem.

Remove Seats

The Charger’s front bucket seat attachment bolts are located under the car. I squirt them with WD-40 to make them easy to remove. Once I remove the bolts, I can lift the seats straight up and out of the vehicle. Note: On bench seat models, it’s best to remove the seat belts with the seats.

I remove the rear seat lower cushion by applying pressure against the lowermost portion of the front of the seat. This begins the release of the seat cushion from the “C”-type retainer clip mounted on the floor pan. Pushing the cushion back and up should release the seat and allow removal.

The upper cushion is usually suspended over the lower cushion. I push the upper cushion back and upward to release it from the hangers. Note: Some models may have attachment bolts located at the base of the upper cushion or may be secured to the body via the rear seat belt attachment points.

Remove Door and Quarter Trim

Aside from the usual array of screws holding the armrest and other trim pieces to the door, you may need to contend with special attachments on the window regulator knob as well as on the inside latch handle. If a screw isn’t visible at the center of either knob, a spring clip retainer, like the one in photo 8, probably holds it on. To remove this clip, you need the door handle tool used in photo 8. This tool slides behind the knob and pushes off the spring clip to release it.

The trim panel itself is attached either with screws (which are visible on the surface of the panel), metal spring-type clips, or possibly plastic clips. Photo 9 shows two different styles of metal clips along with a common type of plastic clip. A door panel tool is used to gently pry the trim panel from the door. Warning! Failure to use this tool (or a similar tool) can result in torn or broken trim panels.

The Charger has a two-piece trim panel setup for the doors and quarter trim areas. I remove the lower piece by prying free the metal clips located around the perimeter of the panel, and then slide the trim piece out of the garnish molding, separating the upper trim piece from the lower one. The upper trim piece is also clipped into place and once the clips are freed the trim piece lifts up and off the inner door structure. I remove the plastic dust shield located between the trim panel and the door facing and store it away.

Remove Garnish Moldings

A garnish molding is any molding in the interior of a vehicle. All other moldings, whether reveal, trim, belt, side, edge, or drip, are on the exterior of the vehicle. Most commonly, garnish moldings run the length of the headliner on each side of a vehicle, around the back glass, and around the windshield.

The best way to determine how garnish moldings are attached is to look for the screws, which are visible if they are holding the molding in place. If screws aren’t present along the face of the garnish molding, then either plastic or metal attachment clips are holding the molding in place. While you should treat any 30-year-old molding with care during removal, treat garnish moldings with special care since you must apply some degree of force to remove them from the vehicle. I use the door trim tool in photo 10 to gently pry the molding away from the body. I then use a light and look behind the molding to determine how it is attached before trying to remove it. I’d rather break a clip than a molding any day.

Remove Headliners

Older vehicles use bow-strung headliners. Removing the headliner means first removing all of the trim such as the sun visors, interior lamps, windshield glass garnish moldings, and back glass garnish moldings around the headliner. Remember that the moldings are old and can break easily. Take your time removing them and don’t worry about breaking the retainer clips, which you can always replace—and in most cases need replacing anyway. Don’t forget to tag and label each molding piece as you remove it.

As I mentioned, most headliners are bow-strung, meaning metal bows spanning the width of the roof panel support the headliner. Usually, the perimeter of the headliner is clipped into place and then glued to the body to hold the fabric taut. I begin by removing the clips and then gently pulling the edges of the headliner free of the adhesive. Once the edges are free, I grasp the center of each bow and carefully pull it downward to release the headliner.

The bows are made of spring steel and are installed with the spring bowed, or tensioned, upward. The ends of each bow are notched into small holes or retainer brackets in the sides of the roof structure. Once I pull the bow downward to release the tension, it slips right out.

Remove Carpet

Before the carpet comes out, I unscrew and remove the kick panels and scuff plates. I make sure that each piece is labeled as I remove it.

Remove the package tray if you haven’t already, and store it where it won’t get damaged. Most package trays are made of fiberboard. They break easily and once broken become trash instead of package trays.

The console goes next. The only problem here is the shifter. Manual shifters have a rubber boot attached to the console while automatic shifters may have only a plastic slide bar to hide the underworkings of the shifter. In either case, removing the shift knob usually frees the shifter from the console. The front and rear of the console are screwed to the floor pan. Look inside the storage compartment or the ashtray on the console to find the rearmost attachment screws and then look along the sides or under the shifter faceplate for the forward attachment screws. Once the screws are removed, the console lifts up and over the shifter. Don’t worry about removing the shifter from the vehicle at this time—you’ll do that later.

PHOTO 5: Seat removal begins by detaching the front bucket seats. The driver’s seat is in rough condition to say the least. The mounting bolts for the seats must be removed from underneath the vehicle.

PHOTO 6: This is the “C” retainer clip mounted to the floor pan under the back seat. The seat can only be removed by pushing it back to free it from the clip then lifting it up and out.

PHOTO 7: The rear upper seat cushion is hung from this clip. Remove the seat by pushing it back and up to free it from the clip.

PHOTO 8: A more commonly found type of window regulator knob retainer is the spring clip. The tool shown with this clip is necessary to remove this type of clip. The tool slips behind the regulator knob to push the retainer clip free of the knob and release the knob from the regulator.

PHOTO 9: Here are three different trim panel retainer clips and the tool I use to remove them. The clip on the far left was used to retain the upper door trim panel on the Charger and is still used today on many vehicles. The center clip was used on the lower door trim panel and is rarely used today. The right clip is a plastic clip found on most vehicles today. It can be used in place of either of the metal clips.

PHOTO 10: I remove the upper trim piece using the same tool while being careful to gently pry each clip free of the doorframe and not damage the trim piece. Once freed, the trim piece can be lifted up and off the doorframe.

PHOTO 11: To remove the headliner, all of the metal clips holding it in place must be removed. We will reuse the clips when we are ready to reinstall the new headliner.

PHOTO 12: With the retainer clips removed we begin working our way around the perimeter of the headliner, pulling it free of the adhesive holding it in place, leaving nothing but the bows that hold the headliner in place.

PHOTO 13: To remove the headliner, gently grasp the bow and pull it down. Since the bow is actually a spring, it will pop down and come free of the retainer clips found along each side of the roof assembly.

PHOTO 14: The kick panels go next. Notice I wear protective gloves to protect myself against “bites” from parts.

PHOTO 15: The scuff plates come out next. I label them and store them with similar parts.

PHOTO 16: Why is it consoles are always full of junk? This one was no exception. The unit comes out in one piece thanks to two bolts located inside this compartment, plus two more located under the shifter.