Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: CompanionHouse Books

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

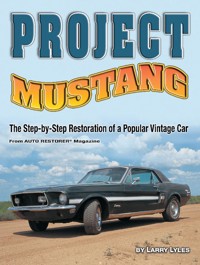

Project Mustang is a complete guide to restoring America's favorite muscle car, written by auto-restoration guru Larry Lyles, a regular contributor to Auto Restorer magazine. In this detailed 23-chapter volume, Lyles walks the car owner from the in-depth inspection of the vehicle and the beginning of the teardown to re-covering the seats and replacing the frame rail…and every step in between. The car restored for the project in the book is a 1968 California Special Mustang. The chapter titles themselves speak for what a straightforward DIY manual Lyles has written, as he details the step-by-step procedure of bringing a very cool rod back to life. Beginning the teardown, exterior and interior; repairing the sheet metal, door, and deck up; removing the major parts (driveshaft, engine, transmission, front suspension, steering system, etc.); removing old point and replacing rust floors; no-weld rust repair; perfecting the metal; working with plastic body filler; priming and sanding; refinishing the components and underside, the door, interior, trunk, and body; wiring the car and installing the doors; applying the coatings, rebuilding the suspension, and installing the brake lines; installing the vinyl top cover, the headliner, and the glass; rebuilding and installing the engine; installing the front sheet metal, emblems, bumpers, stripes, carpet, and console; re-covering the seats; and replacing the frame rails. Each step in every chapter is photographed as the author progresses along, with captions to spell out exactly what has to happen. The book offers helpful advice about choice of tools and tips to make even beginners feel confident about tackling the many steps involved. With nearly forty years experience in repairing, rebuilding, and restoring classic cars (and lots of non-classic ones!), Lyles emphasizes the reader's need to organize his or her project by determining the course of the project, researching suppliers, making lists of parts and their conditions, creating spreadsheets of estimated and actual costs, and photographing each component as a reference for later in case the restoration goes off track. Each chapter ends with a "notes" page for the reader to record his or her progress, making this manual a practical workbook as well. When the reader gets to the final pages of the book and reads the sections "Start the Engine" and "Test Drive the Car," there will be a true sense of accomplishment. An appendix of part suppliers and an index complete the book.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 384

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2007

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Karla Austin, Director of Operations and Product Development

Nick Clemente, Special Consultant

Barbara Kimmel, Managing Editor

Ted Kade, Consulting Editor

Jessica Knott, Production Supervisor

Indexed by Melody Englund

Copyright © 2007 by I-5 Press™.

Photos copyright © 2007 by Larry Lyles.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of I-5 Press™, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in an acknowledged review.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Lyles, Larry.

Project Mustang : the step-by-step restoration of a popular vintage car : from Auto restorer magazine / by Larry Lyles. p. cm. Includes index. ISBN 978-1-933958-03-3 eISBN 978-1-620080-14-6 1. Mustang automobile—Conservation and restoration. I. Auto restorer. II. Title.

TL215.M8L95 2007 629.28’722—dc22

2007002951

I-5 Press™A Division of I-5 Publishing, LLC™3 BurroughsIrvine, California 92618

Printed and bound in Singapore16 15 14 13 12 11 10 09 08 07 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

Contents

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

INTRODUCTION

CHAPTER 1PROJECT MUSTANG

CHAPTER 2BEGINNING THE TEARDOWN: THE EXTERIOR

CHAPTER 3CONTINUING THE TEARDOWN: THE INTERIOR

CHAPTER 4REPAIRING THE SHEET METAL

CHAPTER 5REPAIRING THE DOOR AND THE DECK LID

CHAPTER 6REMOVING THE MAJOR PARTS

CHAPTER 7REMOVING OLD PAINT AND REPLACING RUSTY FLOORS

CHAPTER 8NO-WELD RUST REPAIR

CHAPTER 9PERFECTING THE METAL

CHAPTER 10WORKING WITH PLASTIC BODY FILLER

CHAPTER 11PRIMING AND SANDING

CHAPTER 12REFINISHING THE COMPONENTS AND THE UNDERSIDE

CHAPTER 13REFINISHING THE DOORS, THE INTERIOR, AND THE TRUNK

CHAPTER 14REFINISHING THE BODY

CHAPTER 15WIRING THE CAR AND INSTALLING THE DOORS

CHAPTER 16APPLYING THE COATINGS, REBUILDING THE SUSPENSION, AND INSTALLING THE BRAKE LINES

CHAPTER 17INSTALLING THE VINYL TOP COVER, THE HEADLINER, AND THE GLASS

CHAPTER 18REBUILDING AND INSTALLING THE ENGINE

CHAPTER 19INSTALLING THE FRONT SHEET METAL

CHAPTER 20INSTALLING THE EMBLEMS, THE BUMPERS, THE STRIPES, AND THE CARPET

CHAPTER 21INSTALLING THE CONSOLE AND RE-COVERING THE SEATS

CHAPTER 22REPLACING THE FRAME RAILS

CHAPTER 23COMPLETING PROJECT MUSTANG

APPENDIX

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the people who spent a lot of time and put in a lot of hard work helping transform this tired old Mustang into a very nice California Special.

John Sauer, AAPD; Pat Sikorski, The Antioch Mustang Stable; John Kenemer, American Designers; Auto Restorer magazine; I-5 Press; Troy Willford, California Mustang; John Sloane and Jim Richardson, the Eastwood Company; Perry York, First Paint & Supply; Legendary Auto Interiors; Kevin Marti, Marti Auto Works; Rick Schmidt, National Parts Depot; Norton Abrasives; Tom Eddy, Paddock Parts; Gary Wright, Painless Performance; PPG Automotive Refinishing; R-Blox Sound Control.

A special thanks to Dwayne Roark, the owner of one very nice California Special Mustang, and Ted Kade, editor of Auto Restorer magazine, who helped transform the articles first published in Auto Restorer magazine into such a great book. And finally, thanks to Pat, Bryan, and The Biscuit for their patience and understanding.

Introduction

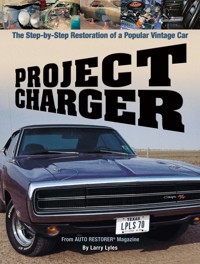

For more than thirty years, I have been repairing, restoring, and rebuilding cars of all types. For the past ten years, I have shared much of that hard-won knowledge with the readers of Auto Restorer magazine and through the publication of two books, Project Charger and Revive Your Ride. If you have read any of my published articles or purchased either of my two books, you already know I use a detailed, hands-on approach to explaining the methods I use to repair and restore old cars. I don’t just grab a handful of tools and dive in expecting you to follow along. I try to keep you, the reader, right there with me as I work.

I feel it isn’t enough to tell you what I did. Anyone can do that. I want you to understand how I did what I did and why I did it that way. But don’t think I am about to bore you with technical jargon or mundane details about the restoration process. Even I can’t stay focused for very long under those conditions. I try to be light but informative, so in the end I believe you not only will have enjoyed what you have read but also will have learned a little more about the fascinating world of automotive restoration.

This book, Project Mustang, follows that same light-but-informative format. I don’t claim to know everything there is to know about restoring a vintage Mustang. For that you will need a whole library of books on the Ford Mustang and perhaps the unlisted phone number for Lee Iacocca. But what I will give you is a solid, systematic course to lead you through the perils and busted knuckles of a total ground-up restoration of one of the world’s most popular muscle cars.

If I could offer one useful piece of advice to anyone beginning the restoration of a vehicle, it would have to be organization. Of course, organization begins by determining where you are going with the project and how you’re going to get there. That means doing a little research, seeking out a few good suppliers, and analyzing the vehicle itself. It also means spending a little time making a list or two and taking a lot of photographs as the project progresses.

If it is part of the car, it gets photographed. If it gets photographed, it gets listed. Over the course of a restoration, I take hundreds of photographs and make several lists. If I somehow become lost in the process or can’t recall how or where a particular part should mount, I then have plenty of reference material to put me back on track. This is why lists are made and why photographs are taken.

I do try to keep the lists simple. Computers make this task even easier. Spreadsheets can be built that list every part of the car, the estimated cost for replacing the parts, and the actual amount of time and money spent purchasing and installing the part.

To that end, I start with a master list that documents the condition of every part removed from the vehicle in the order the parts are removed. If nothing else, this list will serve as a reconstruction blueprint to make sure every part is put back on the vehicle in the reverse order the parts were removed. From the master list, I compile two other lists: a new parts list denoting every part that must be replaced, and a repair and overhaul list that contains the parts that I can repair, refinish, overhaul, and return to the vehicle. The final list, which is nothing more than two columns added to the master list, is a ledger of time and money spent. For example, I spent 1,051 hours restoring Project Charger. I know this fact because I made a list.

For photographic purposes, I use a 35mm film camera. Film is cheap, and I take as many shots as possible. Digital is fine, but you just can’t beat having an actual photograph to keep in the toolbox as reference when needed. Besides, laptops don’t like dust, and restoration shops are full of the stuff.

The car I’m about to restore is a 1968 California Special Mustang. This was Ford’s take on the popular Shelby Mustangs of the sixties and as the name implies was manufactured for the California market. As project cars go, this one is in pretty good condition. It has a little rust and a few dents and shows a little wear and tear, but all in all, this car has the makings of a great project.

I’ll offer you a few tips on where to find parts, how to determine what options came with your car, and, most important of all, how to inspect a car to determine its overall condition.

FIND MUSTANG PARTS

Luckily, new replacement parts for Mustangs are plentiful, and prices for these parts are reasonable. Pick up any Mustang parts catalog, and you will see that almost any part ever made for a Mustang can be purchased without breaking the bank. Some of the better Mustang parts suppliers include the Paddock Parts, National Parts Depot, Marti Auto Works, California Mustang, and Aftermarket Automotive Parts Distributing (AAPD). All of these companies offer free catalogs and list parts online; they carry a parts inventory that has to be considered vast, to say the least. Contact information for all of these companies can be found in the appendix at the end of this book. Of course, when the time comes to place an order with any of these great companies, the first question you’ll be asked is, “What do you have?” If you reply, “It’s a coupe, I think, and I’m pretty sure it’s a ’67, or maybe a ’68, and the engine is blue,” you may have enough information to get the oil changed, but it isn’t going to help much when placing a parts order.

DETERMINE WHAT YOU HAVE

The VIN, or Vehicle Identification Number, is the place to start to determine the exact model of your car. The two most important pieces of information identified on the VIN are the year model and engine size. The VIN plate on the ’68 California Special is located on the right side of the dash panel and is best viewed by looking through the wind-shield. The VIN may also be found on the left fender apron, on the left side of the dash, or on the left door, depending upon the year model of Mustang being restored. To find information specific to your year model, try your favorite search engine on the Internet; far more VIN information than I could ever hope to list here is only a click away.

Here is an example of a typical Ford Mustang VIN: 8R01C123456. The letters and numbers of a VIN contain a great deal of information about a car.

•8: designates this Mustang as a 1968 model

•R: indicates the car was built at the San Jose, California, plant, which helps verify the California Special aspect of this car

•01: indicates it is a coupe

•C: specifies the engine size to be 289 CID

•123456: the last six digits indicate the vehicle production number for the particular year

Knowing my car is a 1968 Mustang, as verified by the VIN, is actually a very small part of determining exactly what this Mustang really is. Verifying that this car is a California Special makes the vehicle more valuable than a standard run-of-the-mill Mustang, but how do I know this car wasn’t simply badged as a California Special to improve its resale value?

To compound the problem of correctly identifying this car, the data plate (or patent plate) normally found on the left door is missing. The data plate could have told me a lot more about the car. The car is painted Augusta green and has a black interior, but without that data plate from the door I can’t be certain Augusta green is the correct color for this car.

One phone call to Marti Auto Works set me on the right path. I gave Marti Auto Works the VIN, they did a quick check of their vast Ford reference file, and presto—the car is indeed a California Special, and Augusta green is the correct color.

While I had Marti Auto Works on the phone, I also placed an order for a duplicate data plate to replace the one missing from the left door. On the 1968 Mustang, this metal tag displays the car’s serial number, which can also be found on the right side of the dash, as well as encoded data about the different equipment options that came on the car.

Other tags available from Marti Auto Works include engine tags, axle tags, body buck tags, carburetor tags, and even owner cards for the glove box. Most of these tags are self-explanatory, but what’s a body buck tag? This is a small metal tag found in the engine compartment, usually on the firewall, that contains the manufacturing data for the body as it moves down the assembly line. For example, the buck tag tells the technician if holes need to be punched in the firewall for air conditioning or lets the painter know which paint combination will go on the car. This tag goes on before the car is painted and usually ends up bent and wrinkled as the different technicians handle the tag.

TIME FOR AN IN-DEPTH INSPECTION

Now that I’m armed with enough good information to let me know this car is indeed a rare pony, I can get to the task of determining the overall condition of the car. This is also the ugly part of any car inspection, but it has to be done.

This is a forty-year-old vehicle, give or take a few years, and a lot can happen to a vehicle over such a long span of time. For example, has the car ever been wrecked? If so, did the repair shop do a good job making the necessary repairs? Body shop repair methods have changed dramatically over the years. The common solution to repairing major collision damage when this car was new was to hit it with a big hammer. Today, if this car was in an accident and repaired correctly, it might be impossible to tell the car had even been wrecked. This just wasn’t the case thirty to forty years ago.

Initial car inspections are often made from twenty feet away. But at that distance, I can’t tell much about a car. To do that, I need to get up close and personal and inspect the exterior and interior of the car.

INSPECTING THE EXTERIOR

I start with the exterior and walk around the car to look for telltale signs that might give a little dent-and-ding history on this pony. I start at the left front wheel. With the front wheels aimed straight ahead, I measure the distance between the rear of the tire and the leading edge of the fender, as shown in photo 1. In this case, the distance is 3½ inches. I’ll compare this measurement to the right side and look for any difference.

This is a crude driveway measurement, but a very telling one. A difference of less than ½ inch between the two sides is acceptable on an unrestored forty-year-old Mustang, but a greater difference could indicate the car has been in trouble at some point and will need to be closely examined by a competent body shop or front-end alignment professional to determine what, if any, problems exist. The difference between the left and right sides of this Mustang measured less than ¼ inch; an acceptable measurement.

PHOTO 1: A rough measurement of the wheel base is taken by measuring the distance between the rear of the front wheel and the leading edge of the fender. This measurement, which is about 3½ inches, is compared with the right front wheel. A difference of more than ½ inch could indicate a structural problem with the car requiring professional help. Both sides measured almost the same, 3½ inches.

Next, I look at the overall condition of the body, starting with the front structure. With the hood closed, I examine the fit of all the panels. In particular, I want to examine the way the hood aligns with both fenders. Notice that I’ve already marked many of the problem areas where the gaps are too narrow with a colored water pencil. A water pencil is a marker that uses water-based color instead of a permanent ink or dye. It washes off easily and won’t harm the finish. Unfortunately, this poor fit was common in its day and is acceptable in some circles even today.

The real test is demonstrated in photo 3. The rear edge of the hood should be parallel to the cowl with no deviation whatsoever. On this car, the right rear corner is tight against the cowl panel, whereas the left rear corner has a wide gap. This indicates that at some point someone made adjustments to the fit of the hood to get it to open and close without binding. This could indicate structural damage to the front of the car, so that’s where I need to look next.

I start by opening the hood to look for obvious signs of structural damage. This usually is found in the form of hammer tracks, slotted fender mounting holes, or damage to the fender aprons or core support that has not been repaired. In the hood, I find evidence that someone had hammered and banged around on the right apron (highlighted by the colored water pencil).

Aside from the hood not fitting and the hammer tracks on the fender apron, another sure sign this car had been in trouble in the past is the left fender marked Taiwan. Ford made its own fenders in 1968, and its factory wasn’t in Taiwan.

Because of all of the above-mentioned problems, I’ll need to take some structural measurements before making the car undrivable. Why? If the engine compartment cross measurements I take are not equal, the car may need to visit a body shop to receive some structural alignment repairs, and I’d rather not have to push it. But that’s for later. For now, I continue my inspection.

The fit of the left door is terrible. This is far worse than what would be expected from a factory fit or even from many years of wear and tear on the door. It doesn’t follow the contour of the quarter at the top and sticks out more than an inch at the bottom. Ideally, I’d like to see this door sitting flush with the quarter panel and exhibiting no more than a ¼-inch gap between the two panels. But even the factory wasn’t that precise. Ford liked to see the panels flush but would tolerate up to a ½-inch gap between the two panels.

PHOTO 2: A visual check of the hood to fender alignment is made. The damaged areas are marked, as are the areas where the fit between the three panels is not acceptable.

PHOTO 3: This gap is critical. Here the left hood to cowl gap is wide, and the right gap is narrow, indicating that the hood as been shifted at some point. This could mean the car has been in a crash and needs to be examined by a competent body repair professional.

PHOTO 4: Another sign this car has been wrecked. Hammer tracks were found along the top of the right fender apron.

PHOTO 5: The fit of this door is far worse than would be expected from forty years of wear and tear.

PHOTO 6: Inside the door, I found the cause of the problem. The outer skin has been replaced, as evidenced by the poor welding job. Also notice that the data plate is missing. Marti Auto Works will make us a new one.

PHOTO 7: This large circular break in the fiberglass deck lid will require some attention later on.

PHOTO 8: Where does the jack instruction decal belong? This photo will tell the tale.

PHOTO 9: A quick way to measure the square condition of an engine compartment is to measure from the rearmost fender mount bolt to the forwardmost fender mount bolt on the opposite side, then repeat this measurement from the opposite side. This Mustang is square to within ¼ inch.

PHOTO 10: Problems, problems. This marker lamp isn’t falling off the fender. The mounting hole was stamped wrong, and this was some body man’s idea of a good fit.

There are more telltale signs of this door having been in trouble before. At some point in this car’s life, the outer panel on the left door had been replaced. This is seen in the poor welding job along the edges of the panel and confirmed by the poor fit of the door.

Moving to the back of the car, I need to inspect the fiberglass deck lid, where I find cracked paint. How do I know the panel is made of fiberglass? The edges are thick and appear molded, not rolled as they would be if the outer skin were made of steel. Also, as evidenced in photo 7, damage to steel doesn’t result in a large ring of cracked paint such as the one found here. Steel bends and dents; fiberglass panels crack in this circular pattern when they’ve been in an impact.

Inside the deck lid are the jacking instructions. A picture is better than all the guesswork in the world when it comes to deciding where to place the new instructional decals once the car has been refinished.

So far, I haven’t found any problem with the car that can’t be overcome. But then, I haven’t finished the inspection of the front unibody structure. Remember the poor-fitting hood? I need to take a closer look at this problem.

Most vehicles have symmetrical engine compartments. This makes taking alignment measurements very easy. I’ve stretched a tape measure across the engine bay from the right rear corner of the fender apron to the front left corner of the core support and noted the measurement. In this case, it’s 56¼ inches. This same measurement is taken from the left rear to the right front; in this case, the measurement is 56 inches. When compared with the first measurement, I have a difference of ¼ inch. Dividing that number in half tells me the front structure of this car is inch out of square. Not much, considering how far the hood sits out of alignment.

Remember the Taiwan fender found on the initial inspection of the car? I already know it fits like a ’53 Cadillac fender on a ’99 Toyota; this poor fit is more than likely the cause of the hood on the Mustang not fitting properly. However, being reasonably sure the front structure is in good alignment, I’m going to forgo aligning the hood until I have all the chrome, glass, moldings, and other hardware removed from the car. I’ll start that in chapter 2. Also, check out photo 10. No, this marker lamp isn’t about to fall out of the hole. The mounting hole was actually stamped that crooked. This fender has other alignment issues that will require some heavy-duty realignment procedures, but that’s for chapter 4.

PHOTO 11: It’s a little difficult to tell what portion of the car this photo shows, but this is the floor pan under the rear seat, a common area to find rust on early model Mustangs. The arrow points to a series of rust holes.

PHOTO 12: The radio surround trim panel will need rebuilding. We’ll send it to Just Dashes for a professional restoration.

INSPECTING THE INTERIOR

Inside the car, I find the typical Mustang problem of rust in the floor pan. The rust is slightly more extensive than most in that it has migrated under the rear seat. However, the rust isn’t bad enough to create any major problems. Aftermarket floor pans are readily available for this vehicle, and installing them won’t be that difficult.

The interior components are in very good condition considering the age of the car, but problems do stick out, and the padded radio surround will require some extensive repair.

Now that I have completed a walk around the car and have determined its overall condition, the next step is to mark all the problem areas found on the body. Every dent, misaligned panel, rust hole, crack, and broken part needs to be marked with a colored water pencil.

Now that I have completed inspecting the Mustang’s exterior and interior, I have a much clearer picture of the work that will be involved in restoring the car. Before I can begin working on the car, however, I need to gather a few tools, have the air conditioning system tested, establish a good working height, and drain the fluids. Once this is done, I can begin the exterior teardown.

TOOLS

Putting this Mustang back on the road is going to require a little more than just the desire to get the job done. I will also need a few tools, starting with an assortment of common hand tools found in almost everybody’s toolbox: end wrenches; sockets; screwdrivers, both flat-blade and Phillips-type; pliers; and hammers.

The tools not found in most toolboxes are those more specifically designed for auto body repair work. Most of these are one-of-a-kind tools and serve a specific function to aide either in tearing down a vehicle or in making needed repairs to a vehicle. These are the types of tools that may not be readily available at the local automotive parts store but are nevertheless necessary for restoration work.

The Eastwood Company supplies many of these hard-to-find tools. Along with each tool that I list, I’m going to include its part number so you can find it easily in the catalog. As I move deeper into this project, I’ll show you where and how these tools are to be used.

Eastwood auto body repair tools include:

•Body Hammer #31219: removes dents and other imperfections in the metal

•Panel Gap Gauge #31129: aligns doors, fenders, hood, and deck lid to achieve a uniform gap between adjacent panels

•Planishing Hammer #28116 PH:shapes replacement patch panels when repairing rust damage

•Reversed Door Trim Tool #52297: safely removes door trim panels attached with metal spring clips

•Shrinking Hammer #31034: removes small areas of stretched metal

PHOTO 1: Specialty tools from Eastwood. From left to right: body hammer, shrinking hammer, reversed door trim tool, wide blade trim tool, door handle clip tool, windshield reveal molding tool, tubing bender, and panel gap gauge.

•Trim Removal Set #52021: includes a wide blade trim tool primarily used to remove plastic door panel clips, a door handle tool, and a windshield clip tool

•Tubing Bender #49041: fabricates brake and fuel lines

Eastwood metalworking dollies include:

•General Purpose Dolly #31032: the work horse of metal-repairing dollies with a unique saddle shape that makes it comfortable to use, and it is almost unlimited in its applications

PHOTO 2: Metal working dollies. From left to right: general-purpose dolly, heel dolly, and metal shrinking dolly.

PHOTO 3: Pneumatic tools. From left to right, top to bottom: ½-inch impact wrench, air chisel, -inch drill, die grinder, and metal nibbler.

PHOTO 4: Pneumatic tools. Left to right, top to bottom: DA sander, mini grinder, mini DA sander, and right angle mini grinder.

PHOTO 5: Sanding blocks. Left to right: 16-inch plastic body filler block, (top) 16-inch wooden handled primer block, 8-inch primer block, and round finish sanding pad; (bottom) 8-inch block, 5-inch block, and soft foam block.

•Heel Dolly #31225: shaped like the heel of a shoe, this dolly is used primarily on curved panels

•Shrinking Dolly #31083: used in conjunction with Shrinking Hammer #31034 to remove small areas of stretched metal

Tools you will find at the local automotive parts store include the following commonly used pneumatic tools:

•Air chisel: makes short work of removing rusted-out panels

•-inch drill: covers tasks from drilling needed holes to drilling out old spot welds

•½-inch-drive impact wrench: removes those “stuck in place for 20 years” bolts and nuts

•Die grinder: cuts metal, removes excess metal after welding, and does a number of other operations that come up only during the heat of panel replacement

•Metal nibbler: valuable when trimming or fabricating new sheet metal replacement panels

Pneumatic tools that are specific to body repair work include:

•Dual action (DA) sander: used to sand or remove old paint

•Mini dual action sander: allows access to difficult-to-reach areas as well as allows finite smoothing of paint nibs once the finish has been applied

•Mini grinder: takes the place of a larger, more cumbersome, full-size grinder

•Right angle polisher/grinder: allows access to difficult-to-reach areas requiring grinding or polishing

Body repair tools that operate only under manual labor include an assortment of sanding blocks. Common sizes include:

•16-inch block: used on huge flat panels to sand plastic body filler

•8-inch block: used for sanding plastic body filler and to sand smaller flat panels and lightly curved surfaces

•5-inch block: used for sanding plastic body filler and to sand small areas on flat panels and deeply contoured panels

•16-inch primer block: used to sand primer and surfacer and to sand large flat surfaces; has a padded sanding surface

•8-inch primer block: used to sand primer and surfacer on smaller flat panels and to sand lightly curved surfaces; has a padded sanding surface

•Soft foam block: used to sand primer and surfacer; can be used to sand small areas but works best when used on highly curved or contoured surfaces

•Round finish sanding block: the round design allows this soft foam block to accept most 1000-, 1500-, and 2000-grit finish sanding discs when sanding clear coats

Once the right tools are in hand, the next consideration is supplies. Here is a list of body repair supplies taken from the Norton line of sanding and prepping products (part numbers are included):

•Norton 40-grit File Paper #23615 and Norton 80-grit File Paper #23614: the 3½ x 18–inch sandpapers are used for block sanding plastic body filler; start with the 40 grit and finish with the 80 grit

•Norton 180-grit roll #31687 and 320-grit roll #31683: 3½-inch-wide rolls of sandpaper that are used primarily for block sanding. The 180 grit allows you to quickly cut and level large primed panels and prep them for repriming, whereas the 320 grit is used as a finishing sandpaper prior to applying the final seal coat.

•Norton 80-grit DA sandpaper #31480, 80-grit sanding disc #31481, 180-grit DA sandpaper #31477, and 320-grit sandpaper #31473: 6-inch-round discs that can be used for many tasks, including removing old paint (80 grit), feathering back old paint around repair areas (180 grit), and final sanding areas not requiring primer (320 grit)

•Speed-Lok grinding disc #38675 and Speed-Lok disc #9185: grind and clean difficult to reach areas

•Bear-Tex Scuff Pads #58000: use anywhere light sanding is needed

•PSA 1000- and 1500-grit discs #31552, #31550: for final sanding clear coats

•¾-inch-wide masking tape #2492: masks off panels or areas of the car not being painted

The result of using the above-mentioned supplies is the need for a top-quality line of refinishing products. For those, I’ve turned to PPG Automotive Refinishing. I’ll explain the necessary additives and mixing ratios once I am ready to use the products. Here is a list of the primary products I’ll be using on this project:

PHOTO 6: Norton body repair supplies. Left to right: 40-grit sandpaper; 80-grit sandpaper; 3-inch, 24-grit sanding disk and arbor; 3-inch cutoff wheels (for use with a die grinder); 24-grit, 5-inch grinder disk; ¾-inch-wide masking tape; structural adhesive; assorted DA sandpaper including 80, 180, and 320 grits; assorted rolled sandpaper including 80, 180, and 320 grits; and a box of scuff pads.

PHOTO 7: PPG professional grade refinishing products. Left to right, top to bottom: DCU 2002 clear, D8072 sealer, D8005 primer/surfacer, DP74LF epoxy primer, DBI black, and BC base coat.

•PPG DCU 2002 Concept Polyurethane Clear: a high quality clear coat used for overall spray applications chosen simply on the merit of my experience with the product

•PPG 2K Chromatic Sealer D8085: a dark gray sealer designed for use over D8005 chromatic 2K AChromatic Surfacer, which is also part of the PPG Global refinishing system

•D8005 2K A-Chromatic Surfacer: a light gray primer/surfacer taken from the PPG Global Re-finishing System and used to cover the epoxy coated surfaces as well as all areas of the vehicle that have been filled or repaired

PHOTO 8: DeVilbiss GFG 670 Plus gravity feed spray gun and the DeVilbiss Sri 630 mini-spray gun.

•PPG DP74LF Epoxy Primer: an epoxy primer that is red oxide in color to match the base primer coat color Ford applied to the vehicle during manufacturing

•Base color coats: colors selected for this car are PPG Global BC #43644 Augusta green poly, and PPG Deltron 2000 DBI 9600 black

For applying the above listed paint products, I’ve selected the following spray guns:

•DeVilbiss GFG 670 Plus spray gun: comes with three different spray tips, 1.2, 1.3, and 1.4 mm and requires 9 cfm at 30 psi when spraying clear coats

•DeVilbiss Sri 630 mini–spray gun: ideal gun for getting into all those tight areas

•Binks M1-G HVLP spray gun: primarily used to spray primer coats and base color coats

SOME GROUND RULES

Total restorations begin from the ground up, and normally that means finding a good working height for the car itself. But in this case, the car is air conditioned, and that means before the car can be disabled and placed on jack stands, the system must be checked by a qualified air conditioning service center to determine if it still holds a charge (many old systems are not charged because of their age). If charged, the service center will drain the system using the appropriate capture equipment. This is not a do-it-yourself operation. Air conditioning system repair requires specific equipment used by certified technicians. Most important, these systems must never be drained into the atmosphere. It is illegal and extremely harmful to the planet.

The good news is that this air conditioning system contains R-12 Freon worth between $30.00 and $90.00 per pound once collected and cleaned. I’ll use that as a bartering chip, I hope, to make a trade with the repair station.

With the car back at the shop, my first step will be to disconnect the battery. My next step will be to place this car at a comfortable working height. I stand about six feet tall, so 18 inches off the floor is about right for me. Depending upon your height, you may want the car positioned either higher or lower. To achieve that height, I’ll set the car on jack stands. To ensure a degree of safety, I’ll also add a 12 x 12 x 1–inch thick wooden platform under each jack stand to prevent the steel jack stands from slipping on the hard concrete floor. Normally, jack stands are placed under the suspension components just inboard of each wheel to properly support the vehicle. But since I will be removing the suspension from this car in the near future, that placement won’t work.

A Mustang is a unibody vehicle, meaning this car doesn’t have a bolt-on frame assembly supporting the drivetrain and suspension components, so placing the jack stands under the frame assembly is out. What I can do is place the jack stands under the unibody frame rails to give the car sufficient support without having the jack stands in the way once I’m ready to remove the suspension components.

The next step in jacking up a car is to compensate for overhang once the car is on the jack stands. Overhang is a body shop term used to describe a condition caused when a vehicle is supported by means other than the suspension, which leaves the engine to basically overhang the front of the unibody structure. This overhang causes undue stress on the body and can result in twisting the body out of alignment. A telltale sign of this overhang effect is to mount the car on the jack stands and open the doors. With the engine still in the car, the doors may not shut. They are suddenly out of alignment due to the weight of the engine straining against the unibody structure.

PHOTO 9: Project Mustang positioned in the shop and placed on jack stands. Notice the wooden platforms under the jack stands to prevent the stands from slipping on the hard concrete. The height measures approximately 18 inches from the floor to the rocker panel.

To compensate for this strain, I place a hydraulic jack under the front cross member and apply just enough upward pressure with the jack to relieve the stress on the unibody structure. The stress has been compensated for when the doors once again open and close without binding. At this point, all four wheels can be removed from the car to allow for better access under the car.

TIP

A little duct tape wrapped around the wheel studs will help protect the threads from damage once the drums are removed from the car.

DRAIN THE FLUIDS

The next step is to drain all the fluids from the vehicle. In this case, that means draining the radiator of antifreeze, the engine of oil, and the transmission of fluid. The Freon has already been drained from the air conditioner.

Radiators are drained via a petcock found near the bottom radiator hose. Be sure to remove the radiator cap to prevent a vacuum within the system. Engines are drained of oil via a drain plug found at the lowest point on the oil pan. Don’t forget to remove the oil filter while under the car. The automatic transmission is drained by carefully removing the square pan on the bottom of the unit. Begin by loosening all 13 of the pan bolts by at least two full turns. Gently pry the pan loose from the case housing. Fluid should begin to flow from around the edges of the pan. Slowly remove the pan bolts one at a time, allowing the pan to tip and begin to drain. Once drained of fluid, the pan must be reinstalled on the transmission to prevent contamination. Properly dispose of all of the old fluids at a local recycling center. Check the Yellow Pages for the center nearest you.

THE TEARDOWN BEGINS

If it is bright and shiny, soft and spongy, or clear and hard, it needs to come off. I want this car stripped of everything but the drivetrain and sheet metal. The drivetrain stays for now because it is easier to remove its items once everything else has been removed. The sheet metal stays because there are too many body lines on this car that don’t line up. Once everything else has been removed from the car, I’ll spend a little quality time with a body hammer and pry bar getting the panels aligned. I’ll concentrate first on tearing down the front of the car then move to the back of the car. I’ll save the interior and glass removal for chapter 3.

PHOTO 10: To compensate for overhang caused by stress on the unibody structure from the weight of the engine, a hydraulic jack is placed under the front cross member with just enough upward bias to support the weight of the engine.

As I disassemble this unit, I note the condition of each molding on the master list for use later when I’m ready to start placing orders for new parts. I also take the time to lay out each part in the order it was removed from the car in an exploded view (much like the illustrations in parts catalogs) and take photographs. These photographs will become extremely valuable a year from now when I’ll be trying to determine what goes where. Don’t forget to number and date all of the photographs once they are developed. This not only gives you an exploded view but also gives you a chronological sequence of events that can be reversed once assembly begins.

TEARING DOWN THE FRONT

I’m working from the front of the car to the rear. I start with the shiny parts on the front of the car. With the exception of the valance panel, everything up here mounts behind the bumper. That means the valance panel has to be removed before the bumper can be removed, and the bumper has to be removed before most of the bolts holding the grille assembly can be accessed for removal.

PHOTO 11: The front bumper is bolted directly to the unibody frame rails and can be removed only after the valance panel has been removed.

PHOTO 12: An exploded view of the grille parts removed from the front of the car. Everything is laid out as it would be found on the car to make assembly easier later on.

To remove the valance, I need to remove several bolts that hold it in place: two on each end, four across the width. I also need to unplug two parking lamps.

To remove the bumper, I remove the two mounting bolts on either side of the front frame rails plus an additional bolt behind each fender near the outermost corners of the bumper. I’m removing the bumper as a unit and will disassemble it later.

Before removing the grille, I had a question about the authenticity of the fog lamps that were mounted on the grille. Ford used several different fog lamps, most of which were round, whereas Shelby had a tendency to use rectangular Lucas brand fog lamps. At first, these Lucas brand lamps appear to be too large for this car, but upon closer inspection, I found the appropriate Ford number, C8WZ-15L 203 A, taken from a 1968 Ford parts book to verify that these are indeed the correct fog lamps for this vehicle.

The grille assembly goes next. This includes all of the moldings surrounding the grille as well as the front molding on the hood. This molding is considered part of the grille and should be stored along with those parts.

Although the headlamp housings could be considered part of the grille assembly, I’m going to leave both of them on the car for now because they will be used to align the front sheet metal panels. Since they bolt directly to the front of the fenders, they will affect the way the fenders align with the hood. They not only have a direct bearing on the gaps between the hood and the fenders but also help determine how far forward the hood can be adjusted, as the leading edge of the hood must align with the leading edge of each headlamp housing once everything has been properly adjusted.

TEARING DOWN THE REAR

After disassembling the front of the car, I move to the rear. The rear bumper mounts with four bolts found inside the trunk compartment above the floor pan on the right and left sides. Once removed, the rear bumper is stored with the front bumper.

The taillamps are mounted in a rear body finish panel with the entire unit being mounted to the rear body panel. I unbolt this unit from the inside of the trunk and remove it as one piece.

Behind the taillamps are the original lamp openings for the Mustang-style taillamps, and these openings have been filled with specially made enclosures. I remove these enclosures and store them with other parts that will require refinishing.

Under the bumper is the rear valance panel. I leave the backup lamp assemblies in the panel for now and remove the valence panel as a complete assembly.

The first model year for factory installed side marker lamps was 1968. Ford’s better idea was to opt for reflectors instead of lamps. I remove these along with the name plates and store them with the taillamp assemblies.

PHOTO 13: An exploded view of the rear body panel components.

Now that both ends of the car have been disassembled, the next step is to tackle the middle of the car. The parts that need to be removed here are the door components, the seats, the seatbelts, the windshield, the glass pieces, the headliner, the top cover, and the console.

DISASSEMBLE THE DOOR

Back in 1968, making the doors uncomplicated and easy to disassemble wasn’t exactly “job one” with Ford. Although the doors aren’t seriously technical to take apart, each mechanism within the doors must be removed in the correct order, or this task can quickly become frustrating, and the urge to pick up a big hammer to help the situation will become extremely great. But resist the urge to smash something, take your time, and you will find that although these doors aren’t the easiest in the world to take apart, they aren’t the most difficult either.

It’s time to bring out the camera. As I said, tearing down the doors on this car isn’t that technical, but they do contain a lot of parts, and it is important to know where and how these parts are removed from the doors.

REMOVING THE DOOR TRIM