12,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

From everyday apps to complex algorithms, Ruha Benjamin cuts through tech-industry hype to understand how emerging technologies can reinforce White supremacy and deepen social inequity. Benjamin argues that automation, far from being a sinister story of racist programmers scheming on the dark web, has the potential to hide, speed up, and deepen discrimination while appearing neutral and even benevolent when compared to the racism of a previous era. Presenting the concept of the "New Jim Code," she shows how a range of discriminatory designs encode inequity by explicitly amplifying racial hierarchies; by ignoring but thereby replicating social divisions; or by aiming to fix racial bias but ultimately doing quite the opposite. Moreover, she makes a compelling case for race itself as a kind of technology, designed to stratify and sanctify social injustice in the architecture of everyday life. This illuminating guide provides conceptual tools for decoding tech promises with sociologically informed skepticism. In doing so, it challenges us to question not only the technologies we are sold but also the ones we ourselves manufacture. Visit the book's free Discussion Guide: www.dropbox.com

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 363

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Cover

Front Matter

Preface

Introduction

Everyday Coding

Move Slower …

Tailoring: Targeting

Why Now?

The Anti-Black Box

Race as Technology

Beyond Techno-Determinism

Beyond Biased Bots

Notes

1 Engineered Inequity

I Tinker, Therefore I Am

Raising Robots

Automating Anti-Blackness

Engineered Inequity

Notes

2 Default Discrimination

Default Discrimination

Predicting Glitches

Systemic Racism Reloaded

Architecture and Algorithms

Notes

3 Coded Exposure

Multiply Exposed

Exposing Whiteness

Exposing Difference

Exposing Science

Exposing Privacy

Exposing Citizenship

Notes

4 Technological Benevolence

Technological Benevolence

Fixing Diversity

Racial Fixes

Fixing Health

Detecting Fixes

Notes

5 Retooling Solidarity, Reimagining Justice

Selling Empathy

Rethinking Design Thinking

Beyond Code-Switching

Audits and Other Abolitionist Tools

Reimagining Technology

Notes

Acknowledgments

Appendix

References

Index

End User License Agreement

Figures

Introduction

Figure 0.1

N-Tech Lab, Ethnicity Recognition

Chapter 1

Figure 1.1

Beauty AI

Figure 1.2

Robot Slaves

Figure 1.3

Overserved

Chapter 2

Figure 2.1

Malcolm Ten

Figure 2.2

Patented PredPol Algorithm

Chapter 3

Figure 3.1

Shirley Card

Figure 3.2

Diverse Shirley

Figure 3.3

Strip Test 7

Chapter 5

Figure 5.1

Appolition

Figure 5.2

White-Collar Crime Risk Zones

Guide

Cover

Table of Contents

Begin Reading

Pages

iii

iv

vii

ix

x

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

158

159

160

161

162

163

164

165

166

167

168

169

170

171

172

173

174

175

176

177

178

179

180

181

182

183

184

185

186

187

188

189

190

191

192

193

194

195

196

197

198

199

200

201

235

236

237

238

239

240

241

242

243

244

245

246

247

248

249

250

251

252

253

254

255

256

257

258

259

260

261

262

263

264

265

266

267

268

269

270

271

272

273

274

275

276

277

278

279

280

281

282

283

284

285

286

RACE AFTER TECHNOLOGY

Abolitionist Tools for the New Jim Code

Ruha Benjamin

polity

Copyright © Ruha Benjamin 2019

The right of Ruha Benjamin to be identified as Author of this Work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

First published in 2019 by Polity Press

Polity Press65 Bridge StreetCambridge CB2 1UR, UK

Polity Press101 Station LandingSuite 300Medford, MA 02155, USA

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purpose of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

ISBN-13: 978-1-5095-2643-7

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication DataNames: Benjamin, Ruha, author.Title: Race after technology : abolitionist tools for the new Jim code / Ruha Benjamin.Description: Medford, MA : Polity, 2019. | Includes bibliographical references and index.Identifiers: LCCN 2018059981 (print) | LCCN 2019015243 (ebook) | ISBN 9781509526437 (Epub) | ISBN 9781509526390 (hardback) | ISBN 9781509526406 (paperback)Subjects: LCSH: Digital divide--United States--21st century. | Information technology--Social aspects--United States--21st century. | African Americans--Social conditions--21st century. | Whites--United States--Social conditions--21st century. | United States--Race relations--21st century. | BISAC: SOCIAL SCIENCE / Demography.Classification: LCC HN90.I56 (ebook) | LCC HN90.I56 B46 2019 (print) | DDC 303.48/330973--dc23LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018059981

The publisher has used its best endeavours to ensure that the URLs for external websites referred to in this book are correct and active at the time of going to press. However, the publisher has no responsibility for the websites and can make no guarantee that a site will remain live or that the content is or will remain appropriate.

Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition.

For further information on Polity, visit our website: politybooks.com

Dedication

All my life I’ve prided myself on being a survivor.

But surviving is just another loop …

Maeve Millay, Westworld1

I should constantly remind myself that the real leap

consists in introducing invention into existence …

In the world through which I travel,

I am endlessly creating myself …

I, the [hu]man of color, want only this:

That the tool never possess the [hu]man.

Black Skin, White Masks, Frantz Fanon2

Notes

1.

Toye 2016.

2.

Fanon 2008, p. 179.

Preface

I spent part of my childhood living with my grandma just off Crenshaw Boulevard in Los Angeles. My school was on the same street as our house, but I still spent many a day trying to coax kids on my block to “play school” with me on my grandma’s huge concrete porch covered with that faux-grass carpet. For the few who would come, I would hand out little slips of paper and write math problems on a small chalkboard until someone would insist that we go play tag or hide-and-seek instead. Needless to say, I didn’t have that many friends! But I still have fond memories of growing up off Crenshaw surrounded by people who took a genuine interest in one another’s well-being and who, to this day, I can feel cheering me on as I continue to play school.

Some of my most vivid memories of growing up also involve the police. Looking out of the backseat window of the car as we passed the playground fence, boys lined up for police pat-downs; or hearing the nonstop rumble of police helicopters overhead, so close that the roof would shake while we all tried to ignore it. Business as usual. Later, as a young mom, anytime I went back to visit I would recall the frustration of trying to keep the kids asleep with the sound and light from the helicopter piercing the window’s thin pane. Like everyone who lives in a heavily policed neighborhood, I grew up with a keen sense of being watched. Family, friends, and neighbors – all of us caught up in a carceral web, in which other people’s safety and freedom are predicated on our containment.

Now, in the age of big data, many of us continue to be monitored and measured, but without the audible rumble of helicopters to which we can point. This doesn’t mean we no longer feel what it’s like to be a problem. We do. This book is my attempt to shine light in the other direction, to decode this subtle but no less hostile form of systemic bias, the New Jim Code.

IntroductionThe New Jim Code

Naming a child is serious business. And if you are not White in the United States, there is much more to it than personal preference. When my younger son was born I wanted to give him an Arabic name to reflect part of our family heritage. But it was not long after 9/11, so of course I hesitated. I already knew he would be profiled as a Black youth and adult, so, like most Black mothers, I had already started mentally sparring those who would try to harm my child, even before he was born. Did I really want to add another round to the fight? Well, the fact is, I am also very stubborn. If you tell me I should not do something, I take that as a dare. So I gave the child an Arabic first and middle name and noted on his birth announcement: “This guarantees he will be flagged anytime he tries to fly.”

If you think I am being hyperbolic, keep in mind that names are racially coded. While they are one of the everyday tools we use to express individuality and connections, they are also markers interacting with numerous technologies, like airport screening systems and police risk assessments, as forms of data. Depending on one’s name, one is more likely to be detained by state actors in the name of “public safety.”

Just as in naming a child, there are many everyday contexts – such as applying for jobs, or shopping – that employ emerging technologies, often to the detriment of those who are racially marked. This book explores how such technologies, which often pose as objective, scientific, or progressive, too often reinforce racism and other forms of inequity. Together, we will work to decode the powerful assumptions and values embedded in the material and digital architecture of our world. And we will be stubborn in our pursuit of a more just and equitable approach to tech – ignoring the voice in our head that says, “No way!” “Impossible!” “Not realistic!” But as activist and educator Mariame Kaba contends, “hope is a discipline.”1 Reality is something we create together, except that so few people have a genuine say in the world in which they are forced to live. Amid so much suffering and injustice, we cannot resign ourselves to this reality we have inherited. It is time to reimagine what is possible. So let’s get to work.

Everyday Coding

Each year I teach an undergraduate course on race and racism and I typically begin the class with an exercise designed to help me get to know the students while introducing the themes we will wrestle with during the semester. What’s in a name? Your family story, your religion, your nationality, your gender identity, your race and ethnicity? What assumptions do you think people make about you on the basis of your name? What about your nicknames – are they chosen or imposed? From intimate patterns in dating and romance to large-scale employment trends, our names can open and shut doors. Like a welcome sign inviting people in or a scary mask repelling and pushing them away, this thing that is most ours is also out of our hands.

The popular book and Netflix documentary Freakonomics describe the process of parents naming their kids as an exercise in branding, positioning children as more or less valuable in a competitive social marketplace. If we are the product, our names are the billboard – a symptom of a larger neoliberal rationale that subsumes all other sociopolitical priorities to “economic growth, competitive positioning, and capital enhancement.”2 My students invariably chuckle when the “baby-naming expert” comes on the screen to help parents “launch” their newest offspring. But the fact remains that naming is serious business. The stakes are high not only because parents’ decisions will follow their children for a lifetime, but also because names reflect much longer histories of conflict and assimilation and signal fierce political struggles – as when US immigrants from Eastern Europe anglicize their names, or African Americans at the height of the Black Power movement took Arabic or African names to oppose White supremacy.

I will admit, something that irks me about conversations regarding naming trends is how distinctly African American names are set apart as comically “made up” – a pattern continued in Freakonomics. This tendency, as I point out to students, is a symptom of the chronic anti-Blackness that pervades even attempts to “celebrate difference.” Blackness is routinely conflated with cultural deficiency, poverty, and pathology … Oh, those poor Black mothers, look at how they misspell “Uneeq.” Not only does this this reek of classism, but it also harbors a willful disregard for the fact that everyone’s names were at one point made up!3

Usually, many of my White students assume that the naming exercise is not about them. “I just have a normal name,” “I was named after my granddad,” “I don’t have an interesting story, prof.” But the presumed blandness of White American culture is a crucial part of our national narrative. Scholars describe the power of this plainness as the invisible “center” against which everything else is compared and as the “norm” against which everyone else is measured. Upon further reflection, what appears to be an absence in terms of being “cultureless” works more like a superpower. Invisibility, with regard to Whiteness, offers immunity. To be unmarked by race allows you to reap the benefits but escape responsibility for your role in an unjust system. Just check out the hashtag #CrimingWhileWhite to read the stories of people who are clearly aware that their Whiteness works for them like an armor and a force field when dealing with the police. A “normal” name is just one of many tools that reinforce racial invisibility.

As a class, then, we begin to understand that all those things dubbed “just ordinary” are also cultural, as they embody values, beliefs, and narratives, and normal names offer some of the most powerful stories of all. If names are social codes that we use to make everyday assessments about people, they are not neutral but racialized, gendered, and classed in predictable ways. Whether in the time of Moses, Malcolm X, or Missy Elliot, names have never grown on trees. They are concocted in cultural laboratories and encoded and infused with meaning and experience – particular histories, longings, and anxieties. And some people, by virtue of their social position, are given more license to experiment with unique names. Basically, status confers cultural value that engenders status, in an ongoing cycle of social reproduction.4

In a classic study of how names impact people’s experience on the job market, researchers show that, all other things being equal, job seekers with White-sounding first names received 50 percent more callbacks from employers than job seekers with Black-sounding names.5 They calculated that the racial gap was equivalent to eight years of relevant work experience, which White applicants did not actually have; and the gap persisted across occupations, industry, employer size – even when employers included the “equal opportunity” clause in their ads.6 With emerging technologies we might assume that racial bias will be more scientifically rooted out. Yet, rather than challenging or overcoming the cycles of inequity, technical fixes too often reinforce and even deepen the status quo. For example, a study by a team of computer scientists at Princeton examined whether a popular algorithm, trained on human writing online, would exhibit the same biased tendencies that psychologists have documented among humans. They found that the algorithm associated White-sounding names with “pleasant” words and Black-sounding names with “unpleasant” ones.7

Such findings demonstrate what I call “the New Jim Code”: the employment of new technologies that reflect and reproduce existing inequities but that are promoted and perceived as more objective or progressive than the discriminatory systems of a previous era.8 Like other kinds of codes that we think of as neutral, “normal” names have power by virtue of their perceived neutrality. They trigger stories about what kind of person is behind the name – their personality and potential, where they come from but also where they should go.

Codes are both reflective and predictive. They have a past and a future. “Alice Tang” comes from a family that values education and is expected to do well in math and science. “Tyrone Jackson” hails from a neighborhood where survival trumps scholastics; and he is expected to excel in sports. More than stereotypes, codes act as narratives, telling us what to expect. As data scientist and Weapons of Math Destruction author Cathy O’Neil observes, “[r]acism is the most slovenly of predictive models. It is powered by haphazard data gathering and spurious correlations, reinforced by institutional inequities, and polluted by confirmation bias.”9

Racial codes are born from the goal of, and facilitate, social control. For instance, in a recent audit of California’s gang database, not only do Blacks and Latinxs constitute 87 percent of those listed, but many of the names turned out to be babies under the age of 1, some of whom were supposedly “self-described gang members.” So far, no one ventures to explain how this could have happened, except by saying that some combination of zip codes and racially coded names constitute a risk.10 Once someone is added to the database, whether they know they are listed or not, they undergo even more surveillance and lose a number of rights.11

Most important, then, is the fact that, once something or someone is coded, this can be hard to change. Think of all of the time and effort it takes for a person to change her name legally. Or, going back to California’s gang database: “Although federal regulations require that people be removed from the database after five years, some records were not scheduled to be removed for more than 100 years.”12 Yet rigidity can also give rise to ingenuity. Think of the proliferation of nicknames, an informal mechanism that allows us to work around legal systems that try to fix us in place. We do not have to embrace the status quo, even though we must still deal with the sometimes dangerous consequences of being illegible, as when a transgender person is “deadnamed” – called their birth name rather than chosen name. Codes, in short, operate within powerful systems of meaning that render some things visible, others invisible, and create a vast array of distortions and dangers.

I share this exercise of how my students and I wrestle with the cultural politics of naming because names are an expressive tool that helps us think about the social and political dimensions of all sorts of technologies explored in this book. From everyday apps to complex algorithms, Race after Technology aims to cut through industry hype to offer a field guide into the world of biased bots, altruistic algorithms, and their many coded cousins. Far from coming upon a sinister story of racist programmers scheming in the dark corners of the web, we will find that the desire for objectivity, efficiency, profitability, and progress fuels the pursuit of technical fixes across many different social arenas. Oh, if only there were a way to slay centuries of racial demons with a social justice bot! But, as we will see, the road to inequity is paved with technical fixes.

Along the way, this book introduces conceptual tools to help us decode the promises of tech with historically and sociologically informed skepticism. I argue that tech fixes often hide, speed up, and even deepen discrimination, while appearing to be neutral or benevolent when compared to the racism of a previous era. This set of practices that I call the New Jim Code encompasses a range of discriminatory designs – some that explicitly work to amplify hierarchies, many that ignore and thus replicate social divisions, and a number that aim to fix racial bias but end up doing the opposite.

Importantly, the attempt to shroud racist systems under the cloak of objectivity has been made before. In The Condemnation of Blackness, historian Khalil Muhammad (2011) reveals how an earlier “racial data revolution” in the nineteenth century marshalled science and statistics to make a “disinterested” case for White superiority:

Racial knowledge that had been dominated by anecdotal, hereditarian, and pseudo-biological theories of race would gradually be transformed by new social scientific theories of race and society and new tools of analysis, namely racial statistics and social surveys. Out of the new methods and data sources, black criminality would emerge, alongside disease and intelligence, as a fundamental measure of black inferiority.13

You might be tempted to see the datafication of injustice in that era as having been much worse than in the present, but I suggest we hold off on easy distinctions because, as we shall see, the language of “progress” is too easily weaponized against those who suffer most under oppressive systems, however sanitized.

Readers are also likely to note how the term New Jim Code draws on The New Jim Crow, Michelle Alexander’s (2012) book that makes a case for how the US carceral system has produced a “new racial caste system” by locking people into a stigmatized group through a colorblind ideology, a way of labeling people as “criminals” that permits legalized discrimination against them. To talk of the new Jim Crow, begs the question: What of the old? “Jim Crow” was first introduced as the title character of an 1832 minstrel show that mocked and denigrated Black people. White people used it not only as a derogatory epithet but also as a way to mark space, “legal and social devices intended to separate, isolate, and subordinate Blacks.”14 And, while it started as a folk concept, it was taken up as an academic shorthand for legalized racial segregation, oppression, and injustice in the US South between the 1890s and the 1950s. It has proven to be an elastic term, used to describe an era, a geographic region, laws, institutions, customs, and a code of behavior that upholds White supremacy.15 Alexander compares the old with the new Jim Crow in a number of ways, but most relevant for this discussion is her emphasis on a shift from explicit racialization to a colorblind ideology that masks the destruction wrought by the carceral system, severely limiting the life chances of those labeled criminals who, by design, are overwhelmingly Black. “Criminal,” in this era, is code for Black, but also for poor, immigrant, second-class, disposable, unwanted, detritus.

What happens when this kind of cultural coding gets embedded into the technical coding of software programs? In a now classic study, computer scientist Latanya Sweeney examined how online search results associated Black names with arrest records at a much higher rate than White names, a phenomenon that she first noticed when Google-searching her own name; and results suggested she had a criminal record.16 The lesson? “Google’s algorithms were optimizing for the racially discriminating patterns of past users who had clicked on these ads, learning the racist preferences of some users and feeding them back to everyone else.”17 In a technical sense, the writer James Baldwin’s insight is prescient: “The great force of history comes from the fact that we carry it within us, are unconsciously controlled by it in many ways, and history is literally present in all that we do.”18 And when these technical codes move beyond the bounds of the carceral system, beyond labeling people as “high” and “low” risk criminals, when automated systems from employment, education, healthcare, and housing come to make decisions about people’s deservedness for all kinds of opportunities, then tech designers are erecting a digital caste system, structured by existing racial inequities that are not just colorblind, as Alexander warns. These tech advances are sold as morally superior because they purport to rise above human bias, even though they could not exist without data produced through histories of exclusion and discrimination.

In fact, as this book shows, colorblindness is no longer even a prerequisite for the New Jim Code. In some cases, technology “sees” racial difference, and this range of vision can involve seemingly positive affirmations or celebrations of presumed cultural differences. And yet we are told that how tech sees “difference” is a more objective reflection of reality than if a mere human produced the same results. Even with the plethora of visibly diverse imagery engendered and circulated through technical advances, particularly social media, bias enters through the backdoor of design optimization in which the humans who create the algorithms are hidden from view.

Move Slower …

Problem solving is at the heart of tech. An algorithm, after all, is a set of instructions, rules, and calculations designed to solve problems. Data for Black Lives co-founder Yeshimabeit Milner reminds us that “[t]he decision to make every Black life count as three-fifths of a person was embedded in the electoral college, an algorithm that continues to be the basis of our current democracy.”19 Thus, even just deciding what problem needs solving requires a host of judgments; and yet we are expected to pay no attention to the man behind the screen.20

As danah boyd and M. C. Elish of the Data & Society Research Institute posit, “[t]he datasets and models used in these systems are not objective representations of reality. They are the culmination of particular tools, people, and power structures that foreground one way of seeing or judging over another.”21 By pulling back the curtain and drawing attention to forms of coded inequity, not only do we become more aware of the social dimensions of technology but we can work together against the emergence of a digital caste system that relies on our naivety when it comes to the neutrality of technology. This problem extends beyond obvious forms of criminalization and surveillance.22 It includes an elaborate social and technical apparatus that governs all areas of life.

The animating force of the New Jim Code is that tech designers encode judgments into technical systems but claim that the racist results of their designs are entirely exterior to the encoding process. Racism thus becomes doubled – magnified and buried under layers of digital denial. There are bad actors in this arena that are easier to spot than others. Facebook executives who denied and lied about their knowledge of Russia’s interference in the 2016 presidential election via social media are perpetrators of the most broadcast violation of public trust to date.23 But the line between bad and “neutral” players is a fuzzy one and there are many tech insiders hiding behind the language of free speech, allowing racist and sexist harassment to run rampant in the digital public square and looking the other way as avowedly bad actors deliberately crash into others with reckless abandon.

For this reason, we should consider how private industry choices are in fact public policy decisions. They are animated by political values influenced strongly by libertarianism, which extols individual autonomy and corporate freedom from government regulation. However, a recent survey of the political views of 600 tech entrepreneurs found that a majority of them favor higher taxes on the rich, social benefits for the poor, single-payer healthcare, environmental regulations, parental leave, immigration protections, and other issues that align with Democratic causes. Yet most of them also staunchly opposed labor unions and government regulation.24 As one observer put it, “Silicon Valley entrepreneurs don’t mind the government regulating other industries, but they prefer Washington to stay out of their own business.”25 For example, while many say they support single-payer healthcare in theory, they are also reluctant to contribute to tax revenue that would fund such an undertaking. So “political values” here is less about party affiliation or what people believe in the abstract and more to do with how the decisions of tech entrepreneurs impact questions of power, ethics, equity, and sociality. In that light, I think the dominant ethos in this arena is best expressed by Facebook’s original motto: “Move Fast and Break Things.” To which we should ask: What about the people and places broken in the process? Residents of Silicon Valley displaced by the spike in housing costs, or Amazon warehouse workers compelled to skip bathroom breaks and pee in bottles.26 “Move Fast, Break People, and Call It Progress”?

“Data sharing,” for instance, sounds like a positive development, streamlining the bulky bureaucracies of government so the public can access goods and services faster. But access goes both ways. If someone is marked “risky” in one arena, that stigma follows him around much more efficiently, streamlining marginalization. A leading Europe-based advocate for workers’ data rights described how she was denied a bank loan despite having a high income and no debt, because the lender had access to her health file, which showed that she had a tumor.27 In the United States, data fusion centers are one of the most pernicious sites of the New Jim Code, coordinating “data-sharing among state and local police, intelligence agencies, and private companies”28 and deepening what Stop LAPD Spying Coalition calls the stalker state. Like other techy euphemisms, “fusion” recalls those trendy restaurants where food looks like art. But the clientele of such upscale eateries is rarely the target of data fusion centers that terrorize the residents of many cities.

If private companies are creating public policies by other means, then I think we should stop calling ourselves “users.” Users get used. We are more like unwitting constituents who, by clicking submit, have authorized tech giants to represent our interests. But there are promising signs that the tide is turning.

According to a recent survey, a growing segment of the public (55 percent, up from 45 percent) wants more regulation of the tech industry, saying that it does more to hurt democracy and free speech than help.29 And company executives are admitting more responsibility for safeguarding against hate speech and harassment on their platforms. For example, Facebook hired thousands more people on its safety and security team and is investing in automated tools to spot toxic content. Following Russia’s disinformation campaign using Facebook ads, the company is now “proactively finding and suspending coordinated networks of accounts and pages aiming to spread propaganda, and telling the world about it when it does. The company has enlisted fact-checkers to help prevent fake news from spreading as broadly as it once did.”30

In November 2018, Zuckerberg held a press call to announce the formation of a “new independent body” that users could turn to if they wanted to appeal a decision made to take down their content. But many observers criticize these attempts to address public concerns as not fully reckoning with the political dimensions of the company’s private decisions. Reporter Kevin Roose summarizes this governance behind closed doors:

Shorter version of this call: Facebook is starting a judicial branch to handle the overflow for its executive branch, which is also its legislative branch, also the whole thing is a monarchy.31

The co-director of the AI Now Research Institute, Kate Crawford, probes further:

Will Facebook’s new Supreme Court just be in the US? Or one for every country where they operate? Which norms and laws rule? Do execs get to overrule the decisions? Finally, why stop at user content? Why not independent oversight of the whole system?”32

The “ruthless code of secrecy” that enshrouds Silicon Valley is one of the major factors fueling public distrust.33 So, too, is the rabid appetite of big tech to consume all in its path, digital and physical real estate alike. “There is so much of life that remains undisrupted.” As one longtime tech consultant to companies including Apple, IBM, and Microsoft put it, “For all intents and purposes, we’re only 35 years into a 75-or 80-year process of moving from analog to digital. The image of Silicon Valley as Nirvana has certainly taken a hit, but the reality is that we the consumers are constantly voting for them.”34 The fact is, the stakes are too high, the harms too widespread, the incentives too enticing, for the public to accept the tech industry’s attempts at self-regulation.

It is revealing, in my view, that many tech insiders choose a more judicious approach to tech when it comes to raising their own kids.35 There are reports of Silicon Valley parents requiring nannies to sign “no-phone contracts”36 and opting to send their children to schools in which devices are banned or introduced slowly, in favor of “pencils, paper, blackboards, and craft materials.”37Move Slower and Protect People? All the while I attend education conferences around the country in which vendors fill massive expo halls to sell educators the latest products couched in a concern that all students deserve access – yet the most privileged refuse it? Those afforded the luxury of opting out are concerned with tech addiction – “On the scale between candy and crack cocaine, it’s closer to crack cocaine,” one CEO said of screens.38 Many are also wary about the lack of data privacy, because access goes both ways with apps and websites that track users’ information.

In fact the author of The Art of Computer Programming, the field’s bible (and some call Knuth himself “the Yoda of Silicon Valley”), recently commented that he feels “algorithms are getting too prominent in the world. It started out that computer scientists were worried nobody was listening to us. Now I’m worried that too many people are listening.”39 To the extent that social elites are able to exercise more control in this arena (at least for now), they also position themselves as digital elites within a hierarchy that allows some modicum of informed refusal at the very top. For the rest of us, nanny contracts and Waldorf tuition are not an option, which is why the notion of a personal right to refuse privately is not a tenable solution.40

The New Jim Code will not be thwarted by simply revising user agreements, as most companies attempted to do in the days following Zuckerberg’s 2018 congressional testimony. And more and more young people seem to know that, as when Brooklyn students staged a walkout to protest a Facebook-designed online program, saying that “it forces them to stare at computers for hours and ‘teach ourselves,’” guaranteeing only 10–15 minutes of “mentoring” each week!41 In fact these students have a lot to teach us about refusing tech fixes for complex social problems that come packaged in catchphrases like “personalized learning.”42 They are sick and tired of being atomized and quantified, of having their personal uniqueness sold to them, one “tailored” experience after another. They’re not buying it. Coded inequity, in short, can be met with collective defiance, with resisting the allure of (depersonalized) personalization and asserting, in this case, the sociality of learning. This kind of defiance calls into question a libertarian ethos that assumes what we all really want is to be left alone, screen in hand, staring at reflections of ourselves. Social theorist Karl Marx might call tech personalization our era’s opium of the masses and encourage us to “just say no,” though he might also point out that not everyone is in an equal position to refuse, owing to existing forms of stratification. Move slower and empower people.

Tailoring: Targeting

In examining how different forms of coded inequity take shape, this text presents a case for understanding race itself as a kind of tool – one designed to stratify and sanctify social injustice as part of the architecture of everyday life. In this way, this book challenges us to question not only the technologies we are sold, but also the ones we manufacture ourselves. For most of US history, White Americans have used race as a tool to denigrate, endanger, and exploit non-White people – openly, explicitly, and without shying away from the deadly demarcations that racial imagination brings to life. And, while overt White supremacy is proudly reasserting itself with the election of Donald Trump in 2016, much of this is newly cloaked in the language of White victimization and false equivalency. What about a White history month? White studies programs? White student unions? No longer content with the power of invisibility, a vocal subset of the population wants to be recognized and celebrated as White – a backlash against the civil rights gains of the mid-twentieth century, the election of the country’s first Black president, diverse representations in popular culture, and, more fundamentally, a refusal to comprehend that, as Baldwin put it, “white is a metaphor for power,” unlike any other color in the rainbow.43

The dominant shift toward multiculturalism has been marked by a move away from one-size-fits-all mass marketing toward ethnically tailored niches that capitalize on calls for diversity. For example, the Netflix movie recommendations that pop up on your screen can entice Black viewers, by using tailored movie posters of Black supporting cast members, to get you to click on an option that you might otherwise pass on.44 Why bother with broader structural changes in casting and media representation, when marketing gurus can make Black actors appear more visible than they really are in the actual film? It may be that the hashtag #OscarsSoWhite drew attention to the overwhelming Whiteness of the Academy Awards, but, so long as algorithms become more tailored, the public will be given the illusion of progress.45

Importantly, Netflix and other platforms that thrive on tailored marketing do not need to ask viewers about their race, because they use prior viewing and search histories as proxies that help them predict who will be attracted to differently cast movie posters. Economic recognition is a ready but inadequate proxy for political representation and social power. This transactional model of citizenship presumes that people’s primary value hinges on the ability to spend money and, in the digital age, expend attention … browsing, clicking, buying. This helps explain why different attempts to opt out of tech-mediated life can itself become criminalized, as it threatens the digital order of things. Analog is antisocial, with emphasis on anti … “what are you trying to hide?”

Meanwhile, multiculturalism’s proponents are usually not interested in facing White supremacy head on. Sure, movies like Crazy Rich Asians and TV shows like Black-ish, Fresh off the Boat, and The Goldbergs do more than target their particular demographics; at times, they offer incisive commentary on the racial–ethnic dynamics of everyday life, drawing viewers of all backgrounds into their stories. Then there is the steady stream of hits coming out of Shondaland that deliberately buck the Hollywood penchant for typecasting. In response to questions about her approach to shows like Grey’s Anatomy and Scandal, Shonda Rhimes says she is not trying to diversify television but to normalize it: “Women, people of color, LGBTQ people equal WAY more than 50 percent of the population. Which means it ain’t out of the ordinary. I am making the world of television look NORMAL.”46

But, whether TV or tech, cosmetic diversity too easily stands in for substantive change, with a focus on feel-good differences like food, language, and dress, not on systemic disadvantages associated with employment, education, and policing. Celebrating diversity, in this way, usually avoids sober truth-telling so as not to ruin the party. Who needs to bother with race or sex disparities in the workplace, when companies can capitalize on stereotypical differences between groups?

The company BIC came out with a line of “BICs For Her” pens that were not only pink, small, and bejeweled, but priced higher than the non-gendered ones. Criticism was swift. Even Business Insider, not exactly known as a feminist news outlet, chimed in: “Finally, there’s a lady’s pen that makes it possible for the gentler sex to write on pink, scented paper: Bic for Her. Remember to dot your i’s with hearts or smiley faces, girls!” Online reviewers were equally fierce and funny:

Finally! For years I’ve had to rely on pencils, or at worst, a twig and some drops of my feminine blood to write down recipes (the only thing a lady should be writing ever) … I had despaired of ever being able to write down said recipes in a permanent manner, though my men-folk assured me that I “shouldn’t worry yer pretty little head.” But, AT LAST! Bic, the great liberator, has released a womanly pen that my gentle baby hands can use without fear of unlady-like callouses and bruises. Thank you, Bic!47

No, thank you, anonymous reviewers! But the last I checked, ladies’ pens are still available for purchase at a friendly online retailer near you, though packaging now includes a nod to “breast cancer awareness,” or what is called pinkwashing – the co-optation of breast cancer to sell products or provide cover for questionable political campaigns.48

Critics launched a similar online campaign against an IBM initiative called Hack a Hair Dryer. In the company’s efforts to encourage girls to enter STEM professions, they relied on tired stereotypes of girls and women as uniquely preoccupied with appearance and grooming:

Sorry @IBM i’m too busy working on lipstick chemistry and writing down formula with little hearts over the i s to #HackAHairDryer”49

Niche marketing, in other words, has a serious downside when tailoring morphs into targeting and stereotypical containment. Despite decades of scholarship on the social fabrication of group identity, tech developers, like their marketing counterparts, are encoding race, ethnicity, and gender as immutable characteristics that can be measured, bought, and sold. Vows of colorblindness are not necessary to shield coded inequity if we believe that scientifically calculated differences are somehow superior to crude human bias.

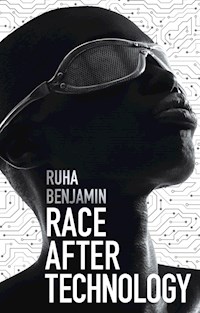

Consider this ad for ethnicity recognition software developed by a Russian company, NTech Lab – which beats Google’s Facenet as the world’s best system for recognition, with 73.3 percent accuracy on 1 million faces (Figure 0.1).50 NTech explains that its algorithm has “practical applications in retail, healthcare, entertainment and other industries by delivering accurate and timely demographic data to enhance the quality of service”; this includes targeted marketing campaigns and more.51

What N-Tech does not mention is that this technology is especially useful to law enforcement and immigration officials and can even be used at mass sporting and cultural events to monitor streaming video feed.52 This shows how multicultural representation, marketed as an individualistic and fun experience, can quickly turn into criminalizing misrepresentation. While some companies such as NTech are already being adopted for purposes of policing, other companies, for example “Diversity Inc,” which I will introduce in the next chapter, are squarely in the ethnic marketing business, and some are even developing techniques to try to bypass human bias. What accounts for this proliferation of racial codification?

Figure 0.1 N-Tech Lab, Ethnicity Recognition

Source: Twitter @mor10, May 12, 2018, 5:46 p.m.

Why Now?

Today the glaring gap between egalitarian principles and inequitable practices is filled with subtler forms of discrimination that give the illusion of progress and neutrality, even as coded inequity makes it easier and faster to produce racist outcomes. Notice that I said outcomes and not beliefs, because it is important for us