Reading R. S. Peters Today E-Book

21,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Serie: Journal of Philosophy of Education

- Sprache: Englisch

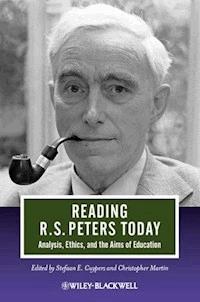

Reading R. S. Peters Today: Analysis, Ethics and the Aims of Education reassesses British philosopher Richard Stanley Peters' educational writings by examining them against the most recent developments in philosophy and practice. * Critically reassesses R. S. Peters, a philosopher who had a profound influence on a generation of educationalists * Brings clarity to a number of key educational questions * Exposes mainstream, orthodox arguments to sympathetic critical scrutiny

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 588

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Ähnliche

The Journal of Philosophy of Education Book Series

The Journal of Philosophy of Education Book Series publishes titles that represent a wide variety of philosophical traditions. They vary from examination of fundamental philosophical issues in their connection with education, to detailed critical engagement with current educational practice or policy from a philosophical point of view. Books in this series promote rigorous thinking on educational matters and identify and criticise the ideological forces shaping education.

Titles in the series include:

The Good Life of Teaching: An Ethics of Professional Practice

Chris Higgins

Reading R. S. Peters Today: Analysis, Ethics, and the Aims of Education

Edited by Stefaan E. Cuypers and Christopher Martin

The Formation of Reason

David Bakhurst

What do Philosophers of Education do? (And how do they do it?)

Edited by Claudia Ruitenberg

Evidence-Based Education Policy: What Evidence? What Basis? Whose Policy?

Edited by David Bridges, Paul Smeyers and Richard Smith

New Philosophies of Learning

Edited by Ruth Cigman and Andrew Davis

The Common School and the Comprehensive Ideal: A Defence by Richard Pring with Complementary Essays

Edited by Mark Halstead and Graham Haydon

Philosophy, Methodology and Educational Research

Edited by David Bridges and Richard D Smith

Philosophy of the Teacher

By Nigel Tubbs

Conformism and Critique in Liberal Society

Edited by Frieda Heyting and Christopher Winch

Retrieving Nature: Education for a Post-Humanist Age

By Michael Bonnett

Education and Practice: Upholding the Integrity of Teaching and Learning

Edited by Joseph Dunne and Pádraig Hogan

Educating Humanity: Bildung in Postmodernity

Edited by Lars Lovlie, Klaus Peter Mortensen and Sven Erik Nordenbo

The Ethics of Educational Research

Edited by Michael Mcnamee and David Bridges

In Defence of High Culture

Edited by John Gingell and Ed Brandon

Enquiries at the Interface: Philosophical Problems of On-Line Education

Edited by Paul Standish and Nigel Blake

The Limits of Educational Assessment

Edited by Andrew Davis

Illusory Freedoms: Liberalism, Education and the Market

Edited by Ruth Jonathan

Quality and Education

Edited by Christopher Winch

This edition first published 2011

Originally published as Volume 43, Supplement 1 of The Journal of Philosophy of Education

Chapters © 2011 The Authors

Editorial organization © 2011 Philosophy of Education Society of Great Britain

Blackwell Publishing was acquired by John Wiley & Sons in February 2007. Blackwell’s publishing program has been merged with Wiley’s global Scientific, Technical, and Medical business to form Wiley-Blackwell.

Registered Office

John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, United Kingdom

Editorial Offices

350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148-5020, USA

9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, UK

The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK

For details of our global editorial offices, for customer services, and for information about how to apply for permission to reuse the copyright material in this book please see our website at www.wiley.com/wiley-blackwell.

The right of Stefaan E. Cuypers and Christopher Martin to be identified as the author of the editorial material in this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher.

Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic books.

Designations used by companies to distinguish their products are often claimed as trademarks. All brand names and product names used in this book are trade names, service marks, trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective owners. The publisher is not associated with any product or vendor mentioned in this book. This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information in regard to the subject matter covered. It is sold on the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering professional services. If professional advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional should be sought.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Reading R. S. Peters today: analysis, ethics, and the aims of education / edited by Stefaan E. Cuypers, Christopher Martin.

p. cm. — (Journal of philosophy of education)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-4443-3296-4 (pbk.)

1. Education–Philosophy. 2. Peters, R. S. (Richard Stanley), 1919- I. Cuypers, Stefaan E., 1958- II. Martin, Christopher.

LB1025.2.R397 2011

370.1–dc22

2011013209

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This book is published in the following electronic formats: ePDFs (9781444346466); Wiley Online Library (9781444346497); ePub (9781444346473); Kindle (9781444346480)

Notes on Contributors

Robin Barrow is Professor of Philosophy of Education at Simon Fraser University, where he was Dean of Education for over ten years. He was previously Reader at the University of Leicester. His recent publications include Plato (Continuum) and An Introduction to Moral Philosophy and Moral Education (Routledge) and, as co-editor, The Sage Handbook of Philosophy of Education (Sage). In 1996 he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada.

Stefaan E. Cuypers is Professor of Philosophy at the Catholic University of Leuven, Belgium. He works in philosophy of mind and philosophy of education. His research interests are autonomy, moral responsibility and R. S. Peters. He is the author of Self-Identity and Personal Autonomy (Ashgate, 2001), the co-author, together with Ishtiyaque Haji, of Moral Responsibility, Authenticity, and Education (Routledge, 2008) and an invited contributor to The Oxford Handbook of Philosophy of Education (2009), edited by Harvey Siegel.

Mike Degenhardt taught philosophy of education at Borough Road and Stockwell Colleges of Education, in London, and subsequently the University of Tasmania. He is the author of Education and the Value of Knowledge (Routledge, 1982) and of a range of papers in the philosophy of education, with particular reference to ethics and teaching. Recently his attention has been turned towards a more historical examination of the roots of the ideas that he has explored in the course of his research and teaching.

Andrea English is Assistant Professor of Philosophy of Education at the Faculty of Education, Mount Saint Vincent University. Her research areas include theories of teaching and learning, John Dewey and pragmatism, continental philosophy of education, especially Herbart, the concept of negativity in education, listening and education. She recently published: with Barbara Stengel, ‘Exploring Fear: Rousseau, Dewey and Freire on Fear and Learning’, Educational Theory 60:5 (2010), pp. 521–542 and ‘Listening as a Teacher: Educative Listening, Interruptions, and Reflective Practice’, Paideusis: International Journal of Philosophy of Education 18:1 (2009), pp. 69–79.

Michael Hand is Reader of Philosophy of Education and Director of Postgraduate Research Programmes at the Institute of Education, University of London. He has research interests in the areas of moral, political, religious and philosophical education. His books include Is Religious Education Possible? (Continuum, 2006), Philosophy in Schools (Continuum, 2008) and, in the Impact policy-related pamphlet series Patriotism in Schools (PESGB, forthcoming).

Graham Haydon is Visiting Fellow at the Institute of Education, University of London, where until recently he was Reader in Philosophy of Education. His many publications on moral education include recently Values for Educational Leadership (Sage, 2007) and Education, Philosophy and the Ethical Environment (Routledge, 2006).

Michael S. Katz is Professor Emeritus of San Jose State University and past President of the North Amereican Philosophy of Education Society. Much of his recent research has focused on ethical issues in teacher-student relationships. Trained at Stanford in analytic philosophy, he has focused recent work on integrating film and literature within moral analyses of concepts such as caring, integrity, trustworthiness, fairness, and respect for persons. He is the lead editor of a volume entitled Education, Democracy and the Moral Life (Springer, 2009), which includes his own analysis of ‘the right to education’. He previously was also the lead editor of a volume, along with Nel Noddings and Kenneth Strike, entitled Justice and Caring: The Search for Common Ground in Education (Teachers College Press, 1999).

Megan J. Laverty is Associate Professor in the Philosophy and Education Program at Teachers College, Columbia University. Her research interests include: philosophy of education, moral philosophy and its significance for education, philosophy of dialogue and dialogical pedagogy, and philosophy with children and adolescents in schools. She is the author of Iris Murdoch’s Ethics: A Consideration of her Romantic Vision (Continuum, 2007) and recently published in Educational Theory and, with Maughn Gregory, in Theory and Research in Education.

Michael Luntley is Professor of Philosophy at the University of Warwick. Recent teaching responsibilities include Wittgenstein, the philosophy of thought and language. His research interests are Wittgenstein, philosophy of mind, and philosophy of education. He is the author of Wittgenstein: meaning and judgement (Blackwell, 2003) and recently published: ‘Understanding expertise’, Journal for Applied Philosophy 26:4 (2009), pp. 356–70, ‘What’s doing? Activity, naming and Wittgenstein’s response to Augustine’, in Wittgenstein’s Philosophical Investigations: A Critical Guide, ed. A. Ahmed, Cambridge University Press, 2010, pp. 30–48, ‘Expectations without content’, Mind & Language 25:2 (2010), pp. 217–236, and ‘What do nurses know?’ Nursing Philosophy 12 (2011), pp. 22–33.

Christopher Martin is a researcher in the Faculty of Medicine, Memorial University of Newfoundland. He is also a lecturer in the Faculty of Education and the Department of English at Memorial University. A former school principal, he holds a PhD in philosophy of education from the Institute of Education, University of London. His research is focused on the ethical and political foundations of education. His most recent work deals with the relationship between the humanities and medical education. His publications include articles in the Journal of Philosophy of Education and Educational Theory, and his book Education as Moral Concept (Continuum) is forthcoming.

Krasimir Stojanov is Professor of Theory and Philosophy of Education at the Bundeswehr University of Munich, Germany. His topics of teaching and research include educational justice, education as a concept of social philosophy, ideology critique. His last monograph Bildung und Anerkennung. Soziale Voraussetzungen von Selbst-Entwicklung und Welt-Erschließung (Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, Wiesbaden, 2006) deals with the relation between education and recognition. Currently he is writing a book on ‘Bildung’ as a Social Phenomenon.

Bryan R. Warnick is an Associate Professor of Philosophy of Education in the School of Educational Policy and Leadership at The Ohio State University. His current research and teaching focus on questions related to the ethics of educational policy and practice, learning theory, philosophy of educational research, and educational technology. He is the author of Imitation and Education (SUNY, 2008) and has published articles in Harvard Educational Review, Educational Researcher, Teachers College Record, Educational Theory, and many other venues.

John White is Emeritus Professor of Philosophy of Education at the Institute of Education, University of London, where he has worked since 1965. His interests are in the aims of education and in educational applications of the philosophy of mind. His recent books include The Child’s Mind (2002), Intelligence, Destiny and Education (2006), What Schools are For and Why (2007), Exploring Well-being in Schools: A guide to making children’s lives more fulfilling (2011), and The Invention of the Secondary Curriculum (forthcoming).

Kevin Williams is Senior Lecturer in Mater Dei Institute of Education, Dublin City University and former President of the Educational Studies Association of Ireland. His books include Education and the Voice of Michael Oakeshott (2007) and Faith and the Nation: Religion, Culture and Schooling in Ireland (2005).

Preface

Writing in 1966, in the closing words of his now classic Ethics and Education, R. S. Peters ponders the possibility that we are suffering from a kind of malaise, accentuated by an overburdened economy. And he sees this malaise as manifested in a disillusionment with the institutions of democracy, including the institutions of education: this is a disillusionment that is experienced by traditionalists and progressives alike. Yet, although he acknowledges this reasonable disappointment, he concludes affirmatively with the recognition that the most worthwhile features of political life are in the institutions that we in fact have. For in the end it is the institutions of democracy that constitute the form of government that a rational person can accept.

Writing nearly half a century later, can we hold on to thoughts such as these? That was a time of prosperity, whereas now we face the varying deeps of a recession. That decade was heralded, so it now seems, with the much-quoted quip of the British Prime Minister Harold Macmillan that ‘most of our people have never had it so good’. He was in fact speaking in 1957, but the remark was to become celebrated as an expression that supposedly epitomised the time. Hence, the general sense that the 1960s was a time of prosperity may make Peters’ remarks about an overburdened economy now seem somewhat surprising. Compare that time with our current straitened circumstances, and you may wonder why disillusionment had set in. After all, you may be tempted further to think, don’t we now face a situation, around the world, in which the financing of educational institutions is strained, where the institutions that finance them are stained, and where the possibilities of democratic access are progressively, surreptitiously curtailed?

There may be some truth in thoughts such as these, but to indulge such a view is conveniently to ignore the increases in real wealth that have been achieved in the intervening decades, as well as the extension of educational provision in so many ways. It was developments in the 1960s, in the economy and in ideas, surely, that provided the ground in which that expansion of education in many significant respects took root. In fact, Peters himself came into the field at a time when his own thinking about education could flourish, and the thoughts that he then disseminated in his writings and teaching had influence around the world. Moreover, apart from his influence through books and articles, Peters was himself a creator of institutions. Thus, in a very real sense, the pages you are now reading owe their existence to Peters’ initiative, with the establishment of the Philosophy of Education Society of Great Britain, and hence with the birth of the Journal of Philosophy of Education, of which he was the first Editor. The expansion of publication and conference activity in philosophy of education that has ensued in subsequent decades owes so much to what he did then. And in this light it is no exaggeration to say that his achievement remains unparalleled.

Can we then turn today to the institutions of education without cynicism, avoiding myths about the past as much as illusions about the future, in the way that Peters urged? In many respects his own writings prompt the kind of serious reflection on education that is the antidote to cynical and idealistic excess. In many respects what he has to say can be turned to the conditions we face today, however much the institutions of our democracies, not least our universities and schools, have changed. And this is precisely what is demonstrated in the chapters that follow. Stefaan Cuypers and Christopher Martin, coming from different academic backgrounds and different cultural contexts, independently developed ideas about the possibilities of a collection that might read Peters’ work against a backdrop of contemporary change—in philosophy, educational policy and practice—but in the end it is their combined initiative that has brought together these assessments and responses from around the world. The journal is grateful to them for their efforts and insight in renewing our sense of the importance of reading R. S. Peters today.

Paul Standish

Introduction: Reading R. S. Peters on Education Today

STEFAAN E. CUYPERS AND CHRISTOPHER MARTIN

Paul Hirst ends his masterly 1986 outline of Richard Stanley Peters’ contribution to the philosophy of education with these words:

Whether or not one agrees with his [Peters’] substantive conclusions on any particular issue it cannot but be recognised that he has introduced new methods and wholly new considerations into the philosophical discussion of educational issues. The result has been a new level of philosophical rigour and with that a new sense of the importance of philosophical considerations for educational decisions. Richard Peters has revolutionised philosophy of education and as the work of all others now engaged in that area bears witness, there can be no going back on the transformation he has brought about (pp. 37–38).

As Hirst rightly notes, while his contribution is still a matter of discussion, all agree on Peters’ status as one of the great founding fathers of contemporary philosophy of education. In the 1960s and 1970s he undertook a uniquely ambitious philosophical project by introducing and developing what might be called a singular analytical paradigm for puzzle-solving in the philosophy of education. This paradigm, whether something to be celebrated or resisted, continues to influence our work today. Peters, born in 1919 in India, who held the chair in the Philosophy of Education at the London University Institute of Education from 1962 until 1983, celebrated his 90th birthday in 2009. Therefore, we wish to take this occasion to critically engage with Peters’ work with the aim of examining the ways in which and the extent to which his contribution has relevance for present day philosophy and educational theory.

The scene of (British) philosophy of education has transformed considerably since Peters’ heyday in the 1960s and 1970s. David Carr’s 1994 state of the art account can be read as an intermediate report on the fortunes of educational philosophy. With the advent of Thatcherism (1979–1990) and the rising influence of managerial conceptions of educational administration and bureaucratic control, the political and institutional circumstances drastically changed. Within the more utilitarian and instrumentalist climate of the 1980s, the philosophy of education took a more ‘practical’ turn and was more concerned with ‘political implications’. At the same time, many educational philosophers resisted an unquestioning acceptance of the market and consumer conceptions of narrowly neo-liberalistic education. Both for their critique and their alternatives, they drew not only on post-empiricist Anglo-American philosophy but also on Continental intellectual traditions such as Phenomenology, Existentialism, (Neo-)Marxism, Structuralism, Critical Theory and Post-Modernism. ‘Thus’, Carr observes, ‘one is as likely to encounter such names as Habermas, Adorno, Horkheimer, Lyotard, Gadamer, Foucault, Derrida, Ricoeur, Althusser or Lacan in a contemporary article on philosophy of education as those of MacIntyre, Taylor or Rorty’ (p. 6).

As of today, the situation has not altered much: at the end of the first decade of the 21st century, philosophy of education is still meritoriously eclectic and cross-cultural in character. True, to the list of names one would have to add Wittgenstein, Heidegger, Arendt, Levinas, Benjamin, Nietzsche, Cavell and McDowell. In addition, recent social changes have, of course, engendered new challenges to be dealt with in educational philosophy. The present-day scene features philosophical reflection (and empirical research) on the ways in which educational systems try to cope with, for example, multiculturalism and cosmopolitanism, globalisation, changing notions of citizenship, environmentalism, as well as with, for example, new conceptions of vocational education, the rise of information and communication technology (ICT) and the restructuring of higher education in both European and North American contexts. All these current issues are approached from different theoretical viewpoints and explored in diverse styles of reflection and research. The recent guidebooks to the field, such as The Blackwell Companion to the Philosophy of Education (Curren, 2003), The Blackwell Guide to the Philosophy of Education (Blake et al., 2003) and The Oxford Handbook of the Philosophy of Education (Siegel, 2009), amply testify to the multi-paradigmatic condition of present day philosophy of education.

Far from considering Peters’ analytical paradigm as somewhat out-dated, all the contributors to this book are of the opinion that it still has an important, if not essential role to play on the scene of philosophy of education today. They go back to Peters in an attempt to carry his thinking further into the future. For that purpose, they take up the main themes of his analytical project in order to seek a fresh look at the ways in which his writings reflect upon current concerns. This book is neither a Festschrift for R. S. Peters, nor a Manifesto for the analytical movement. Though, this being said, one cannot avoid engaging with the analytical claims and methods of an analytical philosopher such as Peters; nor should one avoid pointing out that analytical project’s weaknesses in addition to its merits. The contributions of this book offer an inspirational rereading of Peters and a fruitful exploration of his analytical paradigm in the context of the heterogeneous and multifaceted present day scene of educational philosophy. We now locate the contributors against the backdrop of Peters’ analytical project.

In the early 1960s Peters entered the field of philosophy of education as a first rate philosopher, well-versed in the Ordinary Language Philosophy of Ryle and Austin (for this post-war period in analytical philosophy, see Soames, 2003). Quite naturally for him, philosophy—and, of course, also philosophy of education—is concerned with questions about the analysis of concepts and with questions about the grounds of knowledge, belief, actions and activities. The point of doing conceptual analysis is that it is a necessary preliminary to answering other philosophical questions, especially questions of justification. Consequently, two basic questions delineate Peters’ analytical paradigm in the philosophy of education: 1) What do you mean by ‘education’?—a question of conceptual analysis; and 2) How do you know that ‘education’ is ‘worthwhile’?—a question of justification. He studied not only philosophy but also psychology. This explains his strong interest in philosophical psychology—particularly in the analysis of the concepts of motivation and emotion—and, more pertinent to the field of educational philosophy, in the developmental psychology of Freud, Piaget and Kohlberg. He approached these empirical or quasi-empirical ‘genetic’ psychological theories from the standpoint of moral theory. Hence, another focal question demarcates Peters’ project: 3) How do we adequately conceive of moral development and moral education? These three leading questions serve as a natural outline for the contributions of this book into three sections, with a fourth section serving to place Peters in context:

I. The Conceptual Analysis of Education and Teaching (Barrow, Laverty, Luntley, Warnick, English).

II. The Justification of Educational Aims and the Curriculum (Katz, Hand, White, Martin, Stojanov).

III. Aspects of Ethical Development and Moral Education (Haydon, Cuypers)

IV. Peters in Context (Degenhardt, Williams).

Peters’ analytical project is, in a specific sense, foundational. The sense in which the term ‘foundational’ is used here should not be misunderstood. The project is not epistemologically foundational in the sense of trying to establish a set of infallible axioms for educational theory. As such, it is neutral as to the controversy between foundationalism and anti-foundationalism (coherentism, constructivism, contextualism, etc.) in contemporary epistemology and metaphysics. Peters’ analytical paradigm is conceptually foundational in the sense that it deals with key concepts that are constitutive of the discipline—the philosophy of education—itself. It involves a conceptual inquiry into the very notions of education, learning, teaching, knowledge, curriculum, etc. (for a nearly complete list of these fundamental notions, see Winch and Gingell, 1999). Arguably, the treatment of all other educationally relevant concepts and issues asymmetrically depend upon the analysis of these key concepts. How can one adequately deal with the issue of multicultural education in the school if one has no clear view of education? How can one responsibly apply the concept of ICT in the classroom if one lacks an analysis of knowledge? Unless one has such key concepts in one’s theoretical toolbox, talking philosophy of education quickly degenerates into ‘edu-babble’. In their contributions to this book each author shows how some of the foundational concepts of Peters’ analytical paradigm connect with and elucidate the current concerns mentioned above. While they may not all agree that the particular view of education developed by Peters is entirely cogent or sufficient, they do recognise the extent to which engaging with such key concepts is necessary.

Peters himself concludes his own 1983 state of the art—his philosophical testament in a way—with these words:

Certainly this more low-level, down to earth, type of work [on practical issues] is as important to the future of philosophy of education as higher-level theorising. . . . I do not think [however] that down to earth problems . . . can be adequately or imaginatively dealt with unless the treatment springs from a coherent and explicit philosophical position. . . . But maybe there will be a ‘paradigm shift’ and something very different will take its [the analytical paradigm’s] place. But I have simply no idea what this might be. I would hope, however, that the emphasis on clarity, the producing of arguments, and keeping closely in touch with practice remain (p. 55).

As indicated earlier, no paradigm shift has taken place in the meanwhile. What has come to the surface today is the multi-paradigmatic configuration of the philosophy of education. Yet Peters’ rumination about the future reminds us of the foundational place of the analytical paradigm in this present day configuration. As such, it should play an essential role on the scene of philosophy of education today. Because Peters’ paradigm is philosophical, analytical and foundational, it contributes not only to the clarity and argumentative structure but also to the seriousness of the discipline. It is Peters’ reminder that we must reflect on what it is we are actually claiming when we talk about education. Only by way of such a reflexion can we ensure that an inclusive, multi-paradigmatic philosophy of education, in its attempts to be responsive to the concerns of the moment, does not lose sight of what makes it a valuable and distinctive contribution to the philosophical enterprise.

REFERENCES

Blake, N., Smeyers, P., Smith, R. and Standish, P. (eds) (2003) The Blackwell Guide to the Philosophy of Education (Oxford, Blackwell).

Carr, D. (1994) The Philosophy of Education, Philosophical Books, 35, pp. 1–9.

Curren, R. (ed) (2003) A Companion to the Philosophy of Education (Oxford, Blackwell), pp. 221–31.

Hirst, P. H. (1986) Richard Peters’ Contribution to the Philosophy of Education, in: D. E. Cooper (ed.) Education, Values and Mind. Essays for R. S. Peters (London, Routledge & Kegan Paul), pp. 8–40.

Peters, R. S. (1983) Philosophy of Education, in: P. H. Hirst (ed.) Educational Theory and its Foundation Disciplines (London, Routledge & Kegan Paul), pp. 30–61.

Siegel, H. (ed) (2009) The Oxford Handbook of the Philosophy of Education (New York, Oxford University Press).

Soames, S. (2003) Philosophical Analysis in the Twentieth Century, Volume 2. The Age of Meaning (Princeton, NJ, Princeton University Press).

Winch, C. and Gingell, J. (eds) (1999) Key Concepts in the Philosophy of Education (London, Routledge).

Chapter 1

Was Peters Nearly Right About Education?

ROBIN BARROW

I

Despite my title, my focus in this chapter is more on the question of Peters’ philosophical methodology than on his substantive claims about education, although I shall suggest that broadly speaking he was right about education in his early work, and did not need to conclude subsequently that it was ‘flawed by two major mistakes’ (Peters, 1983, p. 37). Peters did not of course invent or develop a unique kind of philosophical method. But what he did do, very much a man of his time and philosophical background, was rigorously pioneer a form of philosophical analysis in relation to educational discourse. That form or type of philosophical analysis has from the beginning been subject to criticism and is today relatively out of fashion, particularly in the field of education. This is not to suggest that there are no philosophers of education who see themselves as engaged in analysis in the Peters’ tradition, nor that the work of such philosophers is never published. There is no conspiracy theory here. But it is to suggest that much work in philosophy of education and, in particular, much teaching of philosophy of education is not focused upon the kind of sustained and close analysis that Peters advocated.

I shall argue that much of the objection to Peters’ methodology is based on a misunderstanding of what it does and does not involve. Consequently, philosophical analysis is often wrongly seen as one of a number of comparable alternative traditions or approaches to philosophy of education, between which one may or needs to choose, and that, partly consequentially, there is a relative lack of philosophical expertise among today’s nominal ‘philosophers of education’. Furthermore, once his methodology is vindicated, it can perhaps be said that Peters was indeed ‘nearly right about education’, perhaps more so than he subsequently came to believe himself.

In 1975 Peters published a paper entitled ‘Was Plato nearly right about education?’ (Peters, 1975, pp. 3-16). His answer was that Plato was right apart from the fact that he was mistaken in his conception of reason. Few would dispute Peters’ claim that Plato thought that all reasoning led to certainty on the model of geometry, or his view that in this belief Plato was mistaken: we do not necessarily arrive at certain and indisputable truth in the moral sphere, for example, by reasoning. Implicit in recognising this point, of course, is that we can legitimately question the validity of Plato’s or Peters’ conception of education. Again, I doubt that many would be uncomfortable with this. John Wilson sometimes seemed to argue for a strong essentialist position such that education necessarily was what it was, but for the most part contemporary philosophers, no matter how they label themselves, would accept the view that, in W. B. Gallie’s phrase, at least some concepts are ‘essentially contested’, and that it is part of the business of philosophy to argue, sometimes inconclusively, about the various merits of rival conceptions.1 Furthermore, it is naive to imagine that philosophers, by and large, are unaware that particular viewpoints may be materially shaped by various social and psychological considerations. If Plato believed, for example, as some caricatures would have it, that there is one and only one form of relationship possible between human beings that is, always was and always will be, ‘marriage’, then few if any of us today are Platonists. But, to me, that would indeed be a caricature of Plato, and it certainly has no bearing on Peters’ position.2

At this point, however, a crucial and fundamental distinction must be noted. A lack of certainty is not the same thing as arbitrariness. Similarly, to acknowledge room for argument and inconclusive conclusions is not the same thing as saying that the truth is entirely a matter of individual perception. In other words, we must be on our guard against moving from the received wisdom of our day that Plato wrongly thought objective truth was obtainable in all spheres of inquiry to the fashionable conclusion that there is no truth and that all opinions are entirely the product of time and place. Plato’s conception of education may in various ways have been faulty or inadequate, as may Peters’ or yours or mine, but this does not mean that one can have any conception of education one chooses (as indeed reference to ‘faults’ and ‘inadequacy’ in rival conceptions clearly implies).

These introductory remarks relate to my main purpose in this way: I shall argue that Peters’ methodology does not deserve some of the criticism it has received and indeed that he may have recanted more than he should have at later points in his career. So, one part of my concern is to clarify and defend a certain type of philosophical analysis. The other part is to argue that analysis of this sort does not currently enjoy the favour it should. This will involve a brief consideration of what may sometimes be referred to as alternative or rival styles or traditions of philosophy, such as realism, Marxism or postmodernism. But I should note that I am not here primarily concerned to pursue arguments about the inadequacies or shortcomings of alternative approaches.3 Rather, I wish merely to argue for the need for more sustained philosophical analysis such as Peters engaged in, and to establish that in various ways, regardless of their internal coherence, merits and demerits, so-called alternative philosophies (or types or styles of philosophy), are not alternatives at all, because they are not comparable in relevant respects. Deciding, for example, whether to adopt realism or philosophical analysis is, I shall argue, quite evidently a case of apples and pears.

My practical concern is that educational discourse in general and perhaps debate in teacher-education in particular has to a considerable extent reverted to the ‘mush’ famously derided by Peters, albeit ‘mush’ of a far more complex and sophisticated texture than in the past. I want to suggest, therefore, that the teaching of philosophy of education would benefit from a more systematic analytic approach, as opposed to the widespread current tendency to offer isolated courses in such things as ‘existentialism and education’, ‘a phenomenological inquiry into education’ or ‘postmodern perspectives’.

II

One of the earliest and more vituperative criticisms of Peters’ methodology came from David Adelstein in ‘The Philosophy of Education or the Wisdom and Wit of R. S. Peters’ (Adelstein, 1971). Adelstein drew to some extent on Ernest Gellner’s Words and Things (1959), and more broadly on the Marxist tradition then enjoying considerable favour, particularly in the so-called sociology of knowledge. Peters was depicted—as enemies generally seem to be treated in the Marxist-Leninist tradition—as being somehow both a dupe and a hypocritical time-server of the powers that be. But, if we pass beyond the rhetoric and party-posturing, there are some criticisms here that have been more widely held. Perhaps the most notorious of these relates to Peters’ use of such phrases as ‘we would not say . . .’ as in ‘we do not call a person “educated” who has simply mastered a skill’.4 Such phrasing, not surprisingly perhaps, evoked the response: ‘Who are the “we” referred to?’ And to many the answer to that is: ‘“We” are those who think and therefore speak like me’, which in turn was commonly glossed either as those in power or authority or, alternatively, as those who are uncritically subservient to the dominant culture or thought. More widely there was the charge that so-called ‘ordinary language philosophy’ begged every important question by treating some language use as more normal, ordinary or acceptable than others, without warrant. Again there was commonly a class angle introduced, and philosophers were accused of validating certain types of speech such as the Oxford English spoken by most university dons at the expense of working-class speech. In short, linguistic philosophy was criticised as doing no more than giving preference to the thinking implicit in the particular talk of middle-class people and illegitimately claiming that such language was somehow more ‘ordinary’, and hence to be respected, than others. But this is all very confused, not least in the simplistic equation of Oxford philosophy, linguistic philosophy, and ordinary language philosophy with each other and, more importantly, with philosophical analysis in the sense of conceptual analysis.

Gellner, in a book that no analytic philosopher of Peters’ persuasion need have anything but admiration for, made the entirely valid point that words are not things; and anybody who thought that explicating everything that can be said about how the word ‘education’ is used would lead to a definitive account of the phenomenon of education itself, would be sadly mistaken. But did anyone ever seriously think that? Even J. L. Austin, who was undoubtedly and unashamedly interested in How To Do Things With Words (1962), and who, for example, was intrigued by the various applications of a word such as ‘real’, explicitly said that ‘ordinary language has no claim to be the last word, if there is such a thing’ (Austin, 1961, p. 133), and clearly did not imagine for one moment that, by pondering over a question such as what we should call the ‘real’ colour of a deep sea fish, he was contributing in any direct way to a metaphysical question such as ‘what is the nature of reality?’ (if there is such a thing).

Gellner’s thesis has more force against the Wittgensteinian belief that ‘meaning is use’, but even here we should recognise that the claim that the meaning of a word is to be found in its use is distinct from the claim that the meaning of a concept is to be found in the use of the word that denotes it. But note that in any case Austin’s ordinary language philosophy is distinct from Wittgenstein’s theory of meaning and both, I would maintain, are distinct from the kind of philosophical analysis that Peters practiced. Of course he drew eclectically on these and other contemporary ideas, as we all do. But it is crucial to understand that his style of analysis is not to be equated with any one specific school of thought, any one method, or any one procedural principle. And while Gellner was correct to distinguish words and things, it is perhaps unfortunate that he did not equally explicitly go on to distinguish concepts and things, for the fact is that we need to bear in mind the distinction between words and concepts and things. Concepts are not things, both in the sense that some concepts are of abstractions such as love, which are not generally regarded as ‘things’, and in the sense that the concept of a stone is not the same as a particular stone (which is a thing). Despite the fact that formally few would dispute it, many in taking a critical stance towards philosophical analysis of the type practiced by Peters seem to forget this basic point. (While various specific views about language and meaning need to be recognised as distinct, I shall treat ‘philosophical analysis’ of the type I am concerned with as synonymous with ‘conceptual analysis’.)

Conceptual analysis is concerned with trying to explicate a concept: with trying to map out, define or describe the characteristics of an abstract idea such as love or justice or education. It seems certain that, since we are creatures who think in terms of language, any such analysis will begin with some consideration of words. Inevitably, we are going to begin by establishing that ‘to educate’ is not a synonym for ‘to torture’ or ‘to eat’; more than that, we are in most cases going to take for granted some kind of dictionary definition as a starting point: in inquiring into education we are inquiring into what is and is not essential to our idea of bringing up the young. But the word is not the concept: the philosophical concern is not with what the word ‘relevance’, for example, means, which is in fact fairly clear and straightforward, but with what constitutes relevance in that sense.

The limits of the significance of language use are apparent from the beginning. We do not, for example, take account of etymology, save only as being potentially suggestive. That is to say, not only do we not accept a particular view of education simply because it derives from the Latin educere; we specifically repudiate this kind of linguistic argument. (The fact that ‘happiness’ derives from the word ‘hap’, meaning ‘chance’, is not an argument for concluding that people today believe that happiness is purely a matter of chance, still less that it is in fact so. And this is to ignore the point that many etymological claims are questionable. There is in fact no more reason to suppose that education derives from the Latin educere than that it derives from the Latin educare.)5

Not only is philosophical analysis not a species of etymology, it is also simply incorrect to claim that its method is to extrapolate uncritically from the current use of a select group. On the contrary, we explicitly acknowledge both varied contemporary use and, as often as not, historically located use. Thus Woods notes that as a matter of fact sports journalists do talk about the ‘educated left foot’ of the footballer, and Peters recognises that Spartans would have called a certain kind of person ‘educated’ whom the Athenians would not have so called.6 In both cases they proceed to reason to their own conclusions about these varying uses and are in no way bound by them.

Again, it must be stressed that conceptual analysis is not to be defined in term of any particular procedures or methods. There are of course tricks of the trade or gambits that the seasoned philosopher can engage in. For example, sometimes it is helpful to consider the opposite concept, sometimes to consider border-line cases, sometimes indeed to take hints from usage (anybody’s usage) or even etymology. What it is best to do is largely a function of the concept in question, but always the question of how to proceed is a matter of judgement. In the final analysis engaging in conceptual analysis is an imaginative exercise rather than a calculative one. Of course one must take account of various non-conceptual and non-evaluative facts, but fundamentally analyzing the concept of education is a matter of trying to produce reasons for regarding it as more plausible to see it this way than that.

This brings me back to Peters’ use of phrases such as ‘we would not say . . .’. Not only have philosophers such as MacIntyre confused the issue by wrongly equating philosophical analysis with linguistic analysis, they have also tended to interpret this kind of phrasing as evidence that the philosopher is engaged in an empirical survey of linguistic usage.7 But this is clearly not what is going on in such cases. Phrasing such as this is the philosopher’s way of inviting the audience (reader, interlocutor) to think for themselves, and challenging them to disagree. It is the only kind of argument, very often, that characterises what is often loosely called ‘dialectic’. There is no way of ‘proving’ that the mere mastering of the skill of standing on your head is not sufficient to establish that you are educated, at least no way of ‘proving’ in the senses that we are familiar with from other disciplines such as science and mathematics. But while we cannot ‘prove’ it, we can get people to think about it and come to see what they had not hitherto perceived, as a result of which nobody of my acquaintance would accept such a conception. And that is essentially what is involved in Peters’ style of analysis: the attempt to do some extensive and imaginative thinking and to encourage others to consider critically what one has to say. While it is true that we aim to define a term and to explicate the essential characteristics of a concept, it is important to recognise that philosophical analysis is equally concerned with fine discrimination and revealing the logical implications of our concepts.

A little more can be said. Though we cannot define analysis in terms of a specific set of procedures, we can suggest that there are at least four objectives that we should seek to meet. It is widely acknowledged that while we might in principle aim to provide a set of necessary and sufficient conditions for every concept, we cannot in practice succeed in doing so. Many concepts, as I have noted, simply are essentially contested. But we can always make some sort of progress in presenting an account of a concept that is a) clear, b) complete, c) coherent and d) compatible. Attempting to meet these four Cs is ultimately what I would call the business of conceptual analysis.

The value of clarity goes without saying, and it is surely one of the strongest arguments there is for the need for more analytic ability; so much argument in politics, the arts and the humanities in particular is conducted by means of concepts that whatever else they may be are simply unclear (for example, postmodern, bourgeois, embodied meaning, God). In order to explicate a concept, one needs not only to use clear terminology but also, very often, to unpack other concepts involved in the definition. Thus, if we say that education involves the imparting of worthwhile knowledge, that, though clear terminologically, obviously invites further questions about what is involved in worthwhile knowledge. What I mean by aiming for completeness is aiming to ensure explication of such further ideas as are significant in explicating the original. By this time one is likely to have a fairly lengthy, detailed and complex description of the concept in question. It is now important to consider whether it is entirely coherent, by which I refer to its internal consistency. An acceptable analysis obviously must not involve a complex idea that in some way or other is self-contradictory. Finally, if the concept is now clear, complete and coherent it needs to be checked against one’s other knowledge including one’s wider conceptual repertoire, but also including non-conceptual matters such as matters of fact or value—and of course against relevant publicly warranted knowledge. There is something wrong with your understanding of ‘explosive’ if what you define as ‘explosive’ doesn’t explode; and there is something wrong with your definition of happiness if what you define as happiness has everybody weeping in misery.

It is incidentally my view that if we could more successfully analyse our concepts in this way, we might find an unexpected degree of commonality. Thus currently more or less every regime in the world claims to be democratic. Step one (considering usage) would tell us that some people are simply misusing the word in as much as their regime has nothing to do with rule either by or for the people in general. But we would then rapidly find that nonetheless there are a number of distinct regimes which might perhaps be termed democratic. By examining these actual regimes and describing them in terms that are clear, complete, coherent and compatible (in the senses described), we would in all likelihood reasonably conclude that some are not in fact democratic in any plausible sense, but that others though differentiated in detail, are nonetheless equally legitimate forms of democracy. (Not even Plato thought that because all beds partake of the one form of bedness they have to be identical in all respects.)

To recap the argument so far: Peters’ style of philosophical analysis may be regarded as synonymous with conceptual analysis, but is emphatically not to be confused or identified with linguistic philosophy, ordinary language philosophy or the Wittgensteinian equation of meaning with use. It is ultimately concerned with concepts, which are distinct from words, although of course it is acknowledged that any conceptual analysis will have to begin with some basic linguistic clarification. There is no single or determinate set of methods for conducting this analysis; rather, it involves imaginative reflection leading to the setting out of as clear, as complete and as coherent a description of the characteristics of a given idea as may be, and ensuring that the concept thus described is compatible with wider understanding and beliefs. It is a truism that nobody’s account of anything can avoid being influenced by the individual’s particular situation. But it is simply false to assert that analysis of this type is necessarily or even particularly likely to be merely a reinforcement of convention or the status quo.

Indeed, it is something of a paradox that Peters, in arguing for what on the face of it is a minority view (and always has been) of education as a matter of developing understanding for its own sake, certainly at a variance with most governmental conceptions, should have been accused of being a lackey of the powers that be. But then, as noted, criticism of his position has overall been entirely contradictory. To some, what he has to say about education is too specific, to others it is too empty; to some it is too prescriptive, to others not prescriptive enough; to some it is too traditional and conservative, to others it is too idiosyncratic, even iconoclastic.

III

Peters was one of the first people to explicitly seek to analyse the concept of education. Of course others had implicitly or indirectly done so since the time of Plato, and of course others in the 20th century had busied themselves with analysis of various educational concepts. But it was Peters who most obviously made and acted upon the point that if education is the name of our game, then it is on the idea of education itself that we ought to focus. This point has not had the recognition it deserves. It is not a mere detail or a matter of program planning and organisation. There is a clear and great difference between examining certain educational ideas in isolation and doing so in the context of a preliminary inquiry into the very enterprise of education itself. (By analogy, contrast the merely shrewd and knowledgeable lawyer with the lawyer who has given thought also to the nature of law.) One might criticise Peters’ work on the concept of education for being formal and not in itself very determinate, but to some extent, even if this criticism were valid, it misses the point. Even if analysis of the concept of education does not yield a great deal that is both specific and substantive, it will focus the mind on the nature of the activity in which we are engaged.

There are in fact two parts to his analysis of education. First there are the formal criteria. Peters suggests that an educated person is to be distinguished from a trained, a skilled, or a socialised person by four characteristics. All have some kind of knowledge or understanding but the educated person has not merely facts or information but also ‘some understanding of principles for the organization of facts’; he is, secondly, not merely unthinkingly able to regurgitate facts such as historical dates, but is to some degree in some way affected or ‘transformed’ by this knowledge. He sees the world differently than he would otherwise have done as a result of this understanding. Thirdly, the educated man must care about the standards imminent in his field of interest: an educated person takes seriously the standards and procedures of science, for example, and is not merely cognisant of them. Finally, the educated person does not simply have a field of knowledge but what Peters calls ‘cognitive perspective’, meaning a wider framework such that, for example, his scientific knowledge co-exists with historical and cultural understanding.8

Much of the criticism of this part of Peters’ work is not mistaken in its characterisation so much as in its judgement or evaluation. It is, for instance, correct to say that these criteria are formal. That is to say we are told that cognitive perspective is required and we are told what that means, but we are not told in precisely what it consists. But why should this be counted an objection? All concepts have certain formal characteristics and it is as well to start by outlining them. But then it may be said that these criteria are too vague. Here we encounter another common mistake, namely the confusing of breadth with vagueness. A concept may be broad and clear or broad and vague, conversely, it may be specific (narrow) and unclear or specific and precise. In this case, the concept of education is itself in fact a fairly broad one; it is also fairly obviously the case that it is polymorphous. That is to say, while all educated people must be supposed to meet some common criteria if they are indeed to be described equally as ‘educated’, nonetheless the precise form of their education may differ. Thus, we would expect them to have cognitive understanding of some sort, but it may be that different individuals have equal degrees of perspective displayed in different domains. There is, I would suggest, nothing vague or unclear about the four criteria Peters introduces, but they are both broad and formal. That, of course, means that this is both a flexible and generous conception of education: it clarifies our understanding without delimiting possibilities. In the circumstances, it is surprising that some saw Peters as being too prescriptive.

But, secondly, Peters went beyond these four criteria, for he also argued that education necessarily involved the transmission of worthwhile understanding. In view of the fact that Peters talked about certain specific types of knowledge, such as science and history, and particularly in view of his close association with Paul Hirst and the latter’s influential work on forms of knowledge, there is an initial ambiguity here. It is at least arguable that it was never as clear as it might have been whether the claim was that educated people had certain kinds of knowledge (for example, science and history) and such knowledge was worthwhile, or that educated people necessarily had worthwhile knowledge and it could be separately argued that disciplines such as science and history had the requisite value. Nor does Peters’ self-criticism, when writing in 1983 about the state of philosophy of education, help to clarify the matter, for he remarks that he feels his earlier work (particularly in the seminal Ethics and Education, 1966), ’was flawed by two major mistakes. Firstly, a too specific concept of ‘education’ was used which concentrated on its connection [with?] understanding’,9 (which perhaps suggests the first interpretation), while the second flaw was a failure to give ‘a convincing transcendental justification of worthwhile activities’, which suggests the second. He goes on to say that the concept of education is ‘more indeterminate than I used to think. The end or ends towards which processes of learning are seen as developing, e.g. the development of reason which we stressed so much [,?] are aims of education, not part of the concept of “education” itself and will depend on acceptance or rejection of the values of the society in which it takes place’ (Peters, 1983, p. 37).

Although we are now entering into consideration of Peters’ substantive view of education, which is not my primary focus in this chapter, I have to say that I find this recantation very odd. And a recantation indeed it is, for part of Peters’ wider argument had been the claim, surely correct, that the aims of education are intrinsic to it, as opposed to extrinsic, and as such, I should have thought, by definition part of the concept. Furthermore Peters’ ‘admission’ that ‘conceptual analysis has been too self-contained an exercise’, the comment that ‘criteria for a concept are sought in usage of a term without enough attention being paid to the historical or social background and view of human nature which it presupposes’, and his subsequent illustrative observation that usage cannot determine whether ‘teaching’ is only properly used when learning actually occurs, seem to betray some of the confusion of which his critics are guilty (Peters, 1983, pp. 43, 44). As I have argued, the view that ‘criteria for a concept are sought in the usage of a term’ is true only of certain specific approaches to philosophy such as that of some Wittgensteinians, and as a matter of fact it is not true of Peters’ own work in the round. And the obvious conclusion to be drawn from the fact that some people use the word teaching only when learning does take place while others do not, is indeed that linguistic usage is not sufficient to determine conceptual sense (or that we have two distinct concepts).

But Peters’ actual work, both on the concept of education and more generally, is not open to these criticisms. With a wide cultural and historical awareness, and, of course, beginning with some common sense observations about the word in order to locate the argument (we are talking about ‘education’ not ‘swimming’, and, more to the point, about ‘education’ which we want to distinguish from such things as ‘training’ and ‘socialization’), he invites us to recognise that different as our initial substantive views may be, we would not, when we think about it, classify a person with an esoteric set of skills, regardless of how much we admired them, as educated on that account alone. And no more would a classical Spartan or Athenian have done. And I would suggest, à propos Peters’ recantation, that in fact the identification of education and worthwhile knowledge is entirely correct. Granted there is the separate and further question of what knowledge is worthwhile (although here the four formal characteristics have a bearing at least on the question of what is educationally worthwhile), it is surely something that any thoughtful person of any society and era would agree upon: educated people are those who have what is regarded as worthwhile knowledge.

This does mean, of course, that the next and in a sense more important task is to determine what knowledge we take to be worthwhile. But that task, contrary to many a prevailing viewpoint, is not simply a matter of exchanging entirely subjective opinions. It is a question of focusing on the nature of knowledge and on the quality of arguments surrounding particular value claims.

IV

There is a long tradition, in the United States in particular, of teaching philosophy of education by way of various schools of thought or ‘-isms’ (as in ‘realism’, ‘pragmatism’, etc.). Thus, to take a prominent example, Ozmon and Craver’s eighth edition of Philosophical Foundations of Education (2008) has chapters on Idealism, Realism, Eastern Philosophy and Religion, Pragmatism, Reconstructionism, Behaviorism, Existentialism and Phenomenology, Analytic Philosophy, and Marxism, with a final chapter entitled ‘Philosophy, Education and the Challenge of Postmodernism’.