Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Salt

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

Holly Stanton's grandfather was a spy. In Berlin in September 1939; in Norway when the Germans invaded. Sailed back to Orkney by a brave Norwegian, whose family was killed in retaliation. And he kept a diary. Holly has always known that. It's the family story. But when her father finally passes on a transcript of the diary, she finds the 'brave Norwegian' has a name. He is real. But why was a spy writing a diary at all? Part war-time thriller, part exploration of the ethics of story-telling, Reconciliation slips between Occupied Norway and Cambridge, London and the Highlands during the Iraq War and its aftermath. Based on truth but laced with errors and lies, as each layer of the story peels away, we discover just how easily we have been misled. Stories always lie, but sometimes they are the only truth we have. Reconciliation is a clever, exciting and – ironically – honest account of its own bad faith.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 373

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

RECONCILIATION

by

GUY WARE

Holly Stanton’s grandfather was a spy. In Berlin in September 1939; in Norway when the Germans invaded. Sailed back to Orkney by a brave Norwegian, whose family was killed in retaliation. And he kept a diary.

Holly has always known that. It’s the family story. But when her father finally passes on a transcript of the diary, she finds the ‘brave Norwegian’ has a name. He is real. But why was a spy writing a diary at all?

Part war-time thriller, part exploration of the ethics of story-telling, Reconciliation slips between Occupied Norway and Cambridge, London and the Highlands during the Iraq War and its aftermath.

Based on truth but laced with errors and lies, as each layer of the story peels away, we discover just how easily we have been misled. Stories always lie, but sometimes they are the only truth we have. Reconciliation is a clever, exciting and – ironically – honest account of its own bad faith.

PRAISE FOR PREVIOUS WORK

‘This is the Theatre of the Absurd, but crossed with Whitehall farce—Samuel Beckett meets Brian Rix … Guy Ware’s absurdist “bureaucracy thriller” is a fascinating addition to contemporary fiction.’ —DAVID ROSE, Quadrapheme

‘… a brilliantly written, often hilarious, frequently delightful, taut page turner with more depth than you might at first suppose. Like Tom McCarthy by way of Douglas Adams’ —MARTIN KOERNER

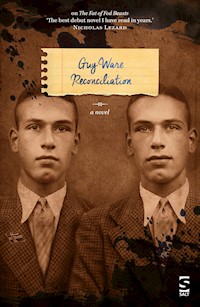

‘The best debut novel I have read in years.’ —NICHOLAS LEZARD, The Guardian

About the author

Guy Ware is the author of two novels and many stories. His collection, You Have 24 Hours to Love Us (Comma, 2012) included the story ‘Hostage’, subsequently included in the Best British Short Stories 2013 (Salt). His first novel, The Fat of Fed Beasts (Salt, 2015), was chosen as a ‘Paperback of the year’ by Nicholas Lezard in the Guardian, and described as ‘Brilliant . . . the best debut novel I have read in years.’

Reconciliation

Guy Ware is the author of two novels and many stories. His collection, You Have 24 Hours to Love Us (Comma, 2012) included the story ‘Hostage’, subsequently included in the Best British Short Stories 2013 (Salt). His first novel, The Fat of Fed Beasts (Salt, 2015), was chosen as a ‘Paperback of the year’ by Nicholas Lezard in the Guardian, and described as ‘Brilliant . . . the best debut novel I have read in years.’

Published by Salt Publishing Ltd

International House, 24 Holborn Viaduct, London EC1A 2BN United Kingdom

All rights reserved

Copyright © Guy Ware, 2017

The right of Guy Ware to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with Section 77 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Salt Publishing.

Salt Publishing 2017

Created by Salt Publishing Ltd

This book is sold subject to the conditions that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

ISBN 978-1-78463-105-5 electronic

To Major A.C.W. Ware and R.M. Ware

An apology

Many novels bear disclaimers: any resemblance, they declare, between the characters depicted and real persons, living or dead, is merely coincidental. But this novel grew from the details of my grandfather’s life, passed on in good faith by his son, my father, and I must apologize for the extent to which my characters fail to resemble their real-life models, for which I am wholly responsible.

By way of reconciliation, I offer here a few facts the reader might bear in mind during what follows:

My father has never been a lawyer.

He has never had a drink problem.

He has never lived in Scotland.

His father was a spy.

To suggest otherwise would be unconscionable.

1 The Gift

§

“That’s where you start.”

Being in IT doesn’t mean I don’t read books. I know how they work.

So I might as well say it started there, on a cold wet Sunday night in February, 2003, with Holly sitting at our attic desk, legs crossed, right over left, twisting from side to side in her office chair – the chair she’d bought when her spine began to ache and she recalled her father nagging on about rowing a boat and having a bad back before she was thirty, which had seemed so far away at the time, but was now so far behind her – and me, kissing the top of her head, the parting in her hair, dropping the typescript on the desk in front of her, my forefinger stretched and pointing to the entry for the 15th of May, and saying:

“That’s where you start. Right there.”

She knew exactly what I meant, but she asked anyway.

“When you write it, that’s where you start.”

I held my hands up, palms outward, playing the impresario. “Your granddad playing Run, Rabbit, Run on a borrowed accordion. One of the Norwegians chucks a shoe his way to shut him up, and he turns back to his diary” – I knocked my knuckles on the desk – “the sound of soldiers hammering on doors getting closer and closer, louder and louder, and the fog refusing to come.”

She didn’t answer.

“Or maybe a couple of days later,” I said, “National Day. May 17th. When their tiny fishing boat is intercepted by a submarine and the captain is ordered – in rough Norwegian – to line up his crew on the deck.”

She looked uncomfortable. I hadn’t done the research then. I had no idea that, technically, May 17th is Constitution Day, the anniversary of the day in 1814 when Norway first adopted the constitution of an independent country, even if most Norwegians refer to it as Nasjonaldagen (National Day) or just May Seventeenth. I was quoting the diary, the transcript Holly’s dad had given her and she’d shown me. That was all I had to go on. I didn’t know then that her granddad celebrated the 17th of May for years afterwards, back in England. But she did. She thought she did. She thought she knew this story, her grandfather’s story, but perhaps it was only now, with me hamming it up, that she could see it: see the small, dirty, working boat, its paint chipped, its winches rusty but serviceable, a boat that did a job, pitching and yawing in a muscular sea as her grandfather climbed up on deck, his face unshaven, his thick, oily sweater identical to Overand’s, because Overand’s wife had pressed it on him, knowing it was important for them to look as much alike, and as much like fishermen, as possible.

She said it probably wasn’t like that, but it was. She knew it was. It was all there, in the diary.

So she said, “Or what about when Overand’s family were all dragged off by the SS, Martin? His wife and children. Should I start there?”

If you didn’t know her, you might have thought she meant it. You might have taken her literally, as if she were an editor discussing a first draft and wondering how to shape the story. But I knew her.

“Could be,” I said. “It’s not in the diary, though, is it? And probably not the place to start. You need to establish him first. The hero.”

Like I say, I read.

“Who?”

“Albert Charles William. Your grandfather.”

She shook her head.

“It’s not a story, Martin.”

Of course it was.

It had always been a story: her granddad, her father’s father, the spy. In Berlin in September 1939, for reasons he never disclosed; in Norway (ditto) when the Germans invaded. Sailed back to England by a brave Norwegian, whose family the Germans killed in retaliation. And he kept a diary.

She’d told me the story years earlier, not making too much of it. We’d been on a demo, which wasn’t unusual, then, a demo against the Gulf War. The first Gulf War. Our first, anyway. We were sitting on the wall around the memorial where, normally, there’d be tramps or teenagers with purple hair drinking cider. Someone started in on what could ever justify war. World War II came up – it always did: the fight against fascism – and I was probably giving it my full “glorious sacrifice of the Red Army” spiel – this being 1991 and there still just about being a Communist Party for me to be in – and she told me about her grandfather, and the Norwegian. Just a couple of sentences, she couldn’t believe she hadn’t told me before. Perhaps she had, and I’d forgotten. We’d been together years by then, after all.

Anyway.

I’d heard her tell other people, too, over the decades we were together. Her grandmother in domestic service; her grandfather in MI6. A major, no less. She’d barely known him – he died when she was young – but she knew the story, and she told it. It was part of who she was.

This was different, though.

This time she finally had the diary in her hands, or at least the transcript that William, her father, had made.

Stories never start where they start though, do they? Not on a cold wet February night in Cambridge, not in May in the middle of the North Sea, not in a Norwegian cottage listening to the sound of soldiers coming closer, not with the outbreak of war, or before the war – it’s always before the war, or after the war, we are always in the middle of things, never the beginning or the end. So we could just as well say this story started the previous day: Saturday – that Saturday: 15th February, 2003 – when I shuffled towards Hyde Park, on the look-out for old comrades, and Holly spent the day at her father’s house, the house she’d grown up in, helping him clear out the books and papers of a lifetime’s work, helping him prepare (as he put it, more than once) to die.

“A bit of a busman’s holiday for you, I’m afraid,” he’d said, ringing to ask if she would help. Holly said she didn’t mind, which I dare say was true. That could be her epitaph: I don’t mind. Now, as he rummaged in the cupboard under the kitchen sink, looking for dustbin bags, she asked if he wanted to start at the top and work down? Or at the bottom and work up?

It was a tall South London terrace: what it lacked in width, and light, it made up for in stairs that seemed to go up forever. As a girl, she told me, she used to dream of finding whole new staircases leading to whole new floors, familiar but strange. The rooms in these dream-floors would be empty, bare pine floorboards stained black around the edges, patterned wallpaper of the sort her parents had stripped whilst she was still a child and never replaced. Sometimes they contained things that had gone missing from the real house – a battered armchair, a favourite doll, her mother. Now the landings were an obstacle course of half-filled cardboard packing cases, of desk lamps and broken radios, hat stands, board games and kettles, all waiting to be packed or – more likely – pitched into the builder’s skip that squatted on the kerb outside, brute and ugly amongst the sleek estates and 4×4s.

Her father straightened up, the black roll of bin bags in his hand like a plastic cosh. “Let’s stick with Horace shall we, Holly? It’s usually best. We’ll begin in media res.”

He talked like that.

I’m doing my best.

The middle of things – the very heart of the house – was his study. That’s where Holly and Ben always went to find him, the room they were pulled towards, or repelled from, by the shifting tides of family rows. A quiet, crepuscular room at the back of the second floor, overlooking the passage, with a fireplace crowded with books and a portrait on the chimneybreast her father said was of her great-grandparents. They were refugees, emigres: asylum seekers avant la lettre. As a child, she’d been fascinated by the man’s white beard, which reached down to his stomach; by the straight, tight parting in the woman’s hair, which left a luminous white strip of scalp in the middle of her head; and by the way the pair of them loomed over her father as he sat at his desk listening to whatever squabble or schoolwork problem she laid out for his adjudication. The rest of the room was shelved from floor to ceiling. Books, periodicals and files, photograph albums, children’s games and jigsaw boxes, telephone directories and ancient briefs were all stuffed and stacked and piled upon each other, without any order or system she could ever detect.

In the middle of the middle of things, with its back to the fireplace, stood a Georgian walnut writing desk, an improbable island of calm amidst the surrounding wreckage. It had been her mother’s once, a present from her father when she married. She had used it as a dressing table; in bitter moments she referred to it as her dowry. When she left for good, Holly’s father threw away the bottles and jars, the lotions and the sprays, and moved it into his study. He had to stand it on blocks – offcuts from the bookcases he was having built at the time – before he could get his knees underneath it comfortably. The Georgians must have been very short indeed, he said – something to do with the diet, no doubt, or the quantity of gin consumed by the wet nurses of the aristocracy. “A beautiful piece of work,” the carpenter said, helping to carry it through from the bedroom and sucking his teeth at the sight of nail varnish on the unpolished surface. “You want to look after that.”

He started with the top drawer. All the predictable crap of a sedentary working life – dried out ballpoint pens, paper clips, staples, a hole punch and its confetti, business cards, empty cheque books, packets of aspirin and alka seltzer, an appointment diary from 1993, another from 1978, a box of matches, a penknife and a silver and bone ink bottle he’d been given by a grateful graduate student from India. He put his hand inside to reach an invisible catch, and pulled the drawer right out of the desk. He nodded to the roll of bin liners he’d brought up from the kitchen and asked Holly to tear one off and hold it open. He lifted the whole drawer into the bag, and turned it upside down. She felt the weightless plastic snap taut.

“Dad?”

“It’s all right. There’s nothing there.”

When he lifted the empty drawer back out she could see ink-stains like blue-black bruises on the unfinished surface of the wood.

The second drawer contained household bills, receipts, bank statements; there was an old letter from the police about a speeding fine; another from a consultant to his GP outlining the results of blood tests from a few years back when, after four decades of high-to-catastrophic alcohol intake, it looked like there might be something wrong with his liver, but wasn’t; and a will in a long, thin manila envelope. He kept the will.

The third drawer contained bundles of letters held together with the faded pink ribbons from barristers’ briefs, or with friable rubber bands that snapped at the slightest touch. On some of the envelopes she recognized his handwriting, on some her mother’s.

He tossed them all into the bag.

“This is more like it,” he said, taking a book from the drawer and passing it to her. Its faded cover was the colour of dead moss. She opened it and read:

“It was your grandfather’s.”

In the middle of the book were half a dozen folded sheets of numbered A4 paper, typed with an old-fashioned typewriter and annotated with hand-written amendments.

“Did you know he was a spy?”

“Yes, Dad. You told me.”

“Of course.”

She said, “The Knickerbocker Press?”

I got back late that evening, still excited. Holly and her father had already eaten as much as they could of a Chinese takeaway, and her father had opened a bottle of whisky. I insisted we all watch the TV news, together.

“You should have been there,” I said. “You too, Bill.”

He said the television was still in the living room but there was nothing left in there to sit on. I went to fetch it and returned, a few moments later, struggling backwards through the kitchen door, lugging the absurdly heavy, bulbous TV over to a counter, where, with a grunt, I set it down next to the microwave Holly’s father never used. (He said it had been a present from Ben, which meant Alice.)

I said, “Christ, Bill. What’s happened in there? It’s like you’ve gone already.”

“Ben took a few pieces.”

Holly said, “Ben’s been? How is he?”

“He’s fine. He sends his love.”

I doubted that. Not that Ben loved his sister, which I supposed he might, but that he would have said so – least of all to their father.

“And Alice?”

William held out his hands in apology, or supplication. “I didn’t ask.”

Holly laughed. “Men.”

“I know. Where would you be without us?”

I unplugged the redundant microwave, and plugged in the television. “Maybe not about to blow the shit out of Iraq.”

William gestured with the whisky bottle, offering me a drink. He said, politely enough, and not as if he were picking a fight: “That’s a tad Greenham Common, isn’t it, Martin? I thought we’d got beyond war being all the fault of male hegemony.” He said it with a smile, not as if he were picking a fight. As if it were the sort of thing he might say, or anybody might say, all the time.

“You should have been there.”

“Perhaps.”

Holly said, “Did you meet anyone we know?”

“That’s the thing. It was too fucking huge. I turned up at the Embankment, and it was like one enormous queue, all the way to Hyde Park. You know how it is. Every time I thought it was about to get going, I’d just bump into a brass band, or jugglers, or student Trots with a megaphone. By the time I got to the park, there were loads of people already leaving, but it was still packed. And there were thousands more behind me, piling in. Hundreds of thousands.”

“Poor you. You hate queues.”

But I wasn’t listening. I was up on my feet, buzzing again. “It was great. Vast. You should have been there. You really should.”

By now I had the TV plugged in, the aerial lead connected to a socket on the kitchen counter William had never used. Even when they all lived there, when Holly and Ben were children and their mother, or the au pair, was making beans on toast for them and a gin and tonic for their father, I guessed the Stantons never watched TV in the kitchen. I switched channels until I saw it again: a million faces, more or less, filling the screen, filling the park.

We watched for banners we might recognize, for unions and Party branches that no longer existed.

I said, “I saw one: Professors of Jurisprudence against the war.”

William had spent half his life in cross-examination and couldn’t be provoked so easily. He poured himself another drink and said, “It might have been better than that infantile Not in my name.”

I knew I shouldn’t rise to the bait, but I said: “It’s telling Tony Blair he hasn’t got our support. It’s an unjustified, illegal war and we don’t want any part in it.”

“Well now,” said William, the professor again, “illegal and unjustified? They’re rather different concepts.”

“There’s no UN mandate.”

“Which might be another matter again . . .”

“So . . . what?” I slumped back in my chair, more disgusted than defeated. It was more comfortable that way.

William said, “We all know a march won’t stop a war.”

“So we just do nothing?”

He held up his hand. “There’ll be a war. A lot of people will die. But we – you and I and Holly, and people like us (an unfortunate phrase, I know, Martin, but apt, in the circumstances) – people like us won’t be killed, or have to kill anyone. At worst we’ll be a bit embarrassed about living in a country that does such things, but our guilt helps precisely no one. So what do we do? We get our excuses in first. Like children. Not in my name is just another way of saying: It wasn’t me.”

“It’s not me.”

“But who cares, Martin? Really? I don’t think this is about your conscience.”

“We have to do what we can.”

He shook his head. “Perhaps.” He swallowed his whisky and held his glass up to the light. “But perhaps this isn’t about us.”

Watching him, I thought, despite his age, there was still a sense of the strength he had always shown, a combination of tension and stillness that suggested resilience more than stress, like steel wire stretched between secure fence posts. It seemed absurd that he should be retiring, leaving London, preparing to die. Whenever he said that, Holly tried to joke him out of it. Her father wasn’t going to die.

He asked if he should open another bottle.

I put my hand over my glass. “Not in my name.”

It was feeble, but he laughed.

Then, in Hyde Park, on television, the shot changed, a view up to the stage, and there she was, in Holly’s father’s kitchen. Cathy.

I had no idea it was going to happen. I told Holly that, afterwards. How could I have known? How could I have guessed that out of all the hours they’d filmed the producers would choose that clip? No one watching would know who Cathy was. But I had been there. I’d seen it at first hand, and she thought I must have known.

I shifted in my chair, pushing it back a fraction from the table, sitting slightly straighter. A union leader wound up his speech, punching his right fist into the palm of his left hand, to muted applause. After a moment’s pause, Cathy stepped toward the microphone.

Holly’s father said, “Isn’t that . . . ?”

And Holly said, “Martin’s ex. Yes, it is.”

Even her father recognized Cathy. He’d only met her a couple of times, back when we were students – Holly, me, Cathy and a couple of others, sharing a house off Mill Road – and he had driven up to visit. Cathy had changed since then, aged, but not by much: something else Holly could hold against her.

“I thought so,” William said. “It’s the eyes.”

I didn’t imagine Holly wanted to discuss Cathy’s eyes and neither, then, did I, so we all watched instead, because it was easier to look at the television than each other.

Cathy was on the platform, not one of the speakers, but part of the machinery. Filling a gap, smoothing out some scheduling hiccough, she stepped forward to the microphone and announced that more marchers were arriving at the park, more still were backed up in Piccadilly and Haymarket, some had not yet left Trafalgar Square all these hours after the rally started. There must be a million, two million of them – of us, she said – and she was greeted with a cheer, a deep, visceral wall of noise that rose like a wave and broke across the stage, crashing over her, washing away the years and leaving her face a beacon of pure, startled, joy. Which I guess was why, even though her face was not familiar and no one would know who Cathy was – except Holly, of course – why that particular clip made it onto the TV news, and Holly saw her, again, for the first time in years.

And I’d insisted we watch it.

Holly stood up, took her glass over to the sink and rinsed it. She filled it with water to take upstairs, to our room, her old room, the one she’d slept in as a child.

As she left, her father was opening another bottle anyway.

She was asleep, I think, not just pretending, and I woke her, coming in. She rolled onto her side, facing the wall, making space in the single bed. I fitted myself to her, my chest against her back, my knees against the back of hers, like a carpenter stacking timber.

She said, “We’re getting a bit old for this.”

Holly read the transcript the next day, Sunday, back in Cambridge, while outside the temperature dropped and the sky filled with cloud, dense and grey like steel wool.

We’d driven home that morning, barely speaking – which was not unusual, I told myself, not a sign of anything in particular, just a familiar trance induced by the steady hum of the tyres and the music on the CD player. She’d brought the transcript back, still tucked inside the book her father kept it in, The Story of Norway, along with the photographs she’d salvaged from her father’s bonfire: one of her grandfather in a folding cardboard frame; one of her mother at seventeen – a studio portrait in a striped silk dress with a broad, tight waist and full petticoats, dated 1958; a handful of family snapshots, leached to chemical browns and inky purples, taken in the family garden, or on beaches around the country, of Holly and her brother, of her mother dressed in Jaeger, in Biba, in increasingly layered and exotic outfits of her own confection, and of her father in well-cut suits, white shirts and thin ties, looking like an associate of the Krays – a diminutive, dangerous one, perhaps – with his fleshy face and hair brushed straight back; none from the last thirty years. Holly said even our physiology seemed to be shaped by fashion. You couldn’t mistake these sixties faces for those of any other decade; no one looked like that now, not even her father, whose face it was, not even her mother, she supposed, though she hadn’t seen her mother since the early seventies.

She read the diary transcript while I cooked: her, sitting at the kitchen table, turning the pages; me, clattering heavy pans and slicing onions. Neither of us mentioned Cathy.

She knew the story.

She picked up the photograph, the one in the cardboard frame. She said, “I never really knew him.”

“No?”

“I was quite young when he died. But I remember he came to stay one Christmas. I think. I can see him – no, I can’t really. I can picture the situation. Somehow, I know it was Christmas, but I don’t remember him eating turkey, or wearing a paper hat, anything like that. He’s sitting in an armchair; I’m looking down at him. He was small, and pale and blond” – she glanced at the photograph again – “I think.”

“How old were you?”

She didn’t answer for a while. “Six? Eight? It’s my only memory of him. Could I have been looking down? Even if he was in a chair?”

“I don’t know. You were there.”

“Maybe. It was Christmas Eve, I think. We were alone. I told him I really wished I could do card tricks, but wasn’t any good at them. His present was a book of magic and tricks with cards. He must have had it wrapped already. It was there, under the tree. Can you imagine how happy he must have been? Listening to me chattering on like that, knowing what was going to happen in the morning, but keeping it to himself?”

I scraped the onions into the pan with a knife that caught the light and flashed like a fish. I said, “I can imagine. But could you? Then?”

“I don’t know.”

She remembered the story, such as it was, but not the book, or any of the tricks. She couldn’t remember Christmas Day itself, she said, the presents in the sack at the end of her bed, more under the tree, her grandfather smiling as she unwrapped his gift. She had remembered a chain of events, a story. A story in which she’d accidentally done something good, something selfless. She wouldn’t have known it at the time, could only have worked it out much later, as an adult, when her grandfather was already dead. In the end it was a story about her, not him, and she had no way of knowing now how much of it was true.

“I know he smoked a pipe. I remember that. There were racks of them in his house. They were hard and shiny and rather smelly. But, you know, I can’t actually remember him with a pipe in his mouth.”

Because there wasn’t one in the photo?

“But you did know he was a spy?”

“Yes. No.”

I turned back to the stove.

“Not at the time. I knew he’d been in the navy. After he died my dad talked more about him. I’m pretty sure that’s when I learned he’d been in MI6. That he’d been a spy; that he was in Norway at the start of the war, and had been rescued. That’s when I heard about the diary. But, Martin? I didn’t really understand it. Not really. Not until today.”

After dinner we went up to the attic room and she read the transcript again, while I lay on the sofa watching the new war grinding into gear on television with the sound down low. When she’d finished, she gave it to me to read, while she sat in her chair – the one with the levers and wheels and pumps that would stop her spine curling like a leaf – twisting from side to side, waiting for my verdict.

What was she expecting?

I stood and dropped the typescript back on the desk in front of her, tapped it with my forefinger and said: “That’s where you start. Right there.”

When she said it wasn’t a story, she knew that wasn’t true.

When she asked if she should start instead with the SS dragging off the Norwegian’s family, she was only stalling.

She said, “He has a name, Martin. I never knew that.”

That, when you got down to it, was what she’d understood.

“Everybody has a name.”

“Of course. Obviously I knew he had a name. But I didn’t know what it was. I’d never heard it. Dad never mentioned it. Not once. I’m sure. It was always the Norwegian: a brave Norwegian. But the brave Norwegian who sailed my grandfather out of trouble had a name: Overand. He had a wife and children. Who must have been called Overand, too.”

“Which is great. You can track them down.”

“They were killed, Martin. Executed. That’s the point. He, the brave Norwegian – Overand – left them behind to save my grandfather, and they were executed.”

Which, actually, she didn’t know for sure.

It wasn’t in the transcript – how could it be? The diary recorded a successful rescue, a return to Britain – but it was still part of the story. It always had been, as far as she knew. Really, it was the point of the story, just as her grandfather’s happiness had been the point of her story.

I said, “Their family, then. There must be someone.”

She could have verified the story; she could have tried.

She paused, her face blank. I imagined her knocking at the door of a small wooden house in Stavanger, pictured the door opening and her saying: Herr Overand? My name is Holly Stanton. I wrote to you about your great uncle? She may have been thinking something similar, thinking she could not possibly do that.

She said, “I wanted you to understand. That’s why I showed it to you.”

I understood it was an opportunity. A chance for her to do something other than the job she always moaned about but always – when I told her to do something else, then – said she didn’t really mind.

I said, “I understand. I do. It’s a gift.”

She didn’t respond.

“For a book. Think about it, Holly. Family memoir. War-time resistance, heroism and atrocity; post-war reticence and suppressed memory. A total gift.”

I’m no expert, but I could see that.

When she said she couldn’t do it, she didn’t mean she couldn’t. She meant she wouldn’t. That she didn’t want to. That she was afraid to. She said her father would say she had no locus standi, no standing, no rights in the case. But did she believe it? Or was it simply that she didn’t have the stomach for it, the splinter of ice in the heart?

She said, “It’s not my story.”

She must have known that wasn’t true, either.

I said her father had given her the transcript for a reason; she just said it wasn’t her story. She said she wouldn’t (wouldn’t, you see – not couldn’t) appropriate other people’s tragedy.

I laughed. It sounded so pompous.

She said, “It’s not about me. I won’t be a hyena, Martin.”

I told her it would be a crime to waste it. That she owed it to her grandfather. To Overand. I said, “He sacrificed his family for your grandfather. For you, in a way. Don’t you think you owe them something?”

All the same, she said she wouldn’t do it.

She said, “It’s not about me.”

Over the weeks that followed, we had three conversations, many times.

We talked about the coming war, its legality, the existence or otherwise of weapons of mass destruction, and whether or not Hans Blix and his UN inspectors should be withdrawn or allowed to complete their task; about oil, and the criminal and irresponsible fatuity of linking Saddam Hussein with Al Qaeda. It was the easiest topic for us to discuss in those weeks: it reinforced our preconceptions and comfortably indulged our millennial doom. Holly and I – and people like us – would not die; but we would be right.

The second conversation, more fleeting and fraught, concerned Holly’s approaching birthday and what, if anything, she wanted for a present. She said, “Nothing.” She always did. It was an almost-joke between us. Every birthday, every Christmas, I’d ask, and she’d say: “Nothing,” and I’d wind up getting something not too far wide of the mark, until the year I saw it through and bought her nothing. I expected her to be upset; but she was relieved, which was worse. This year, however, she was going to be forty, a big, round number. And still, when I asked, which I did, more than once, she said: “Nothing”.

Finally, most difficult of all, we talked about her grandfather’s diary. I started it over and over again, despite myself, despite her.

I’d say, “How come you never found the diary?”

The question must have occurred to her – how could it not?

She’d say, “It’s a long time since he died. Dad must have lost it. Or maybe Mum took it by mistake when she left. Or burned it. How do I know?”

She would be no more convinced than I.

“So your dad keeps the transcript for thirty years – right there, in his desk drawer, at his side for all that time. He asks you round to help clear out and – bingo! – there it is, in practically the first place he looks – but he loses the original?”

“It’s possible.”

“Anything’s possible.”

❦

As February bled into March, we saw less and less of each other. When I wasn’t at work, I was at a meeting, a committee, a demonstration, or I was upstairs, in the attic, hammering away at the laptop.

One evening when she came home late from work, I was still in my dressing gown, lit only by the glow from my computer screen. I hadn’t shaved or washed, or, to be honest, moved much from my desk since morning. She asked if I’d had a good day. I knew she was trying to keep the sarcasm out of her voice, because she didn’t really want to fight, so I said, “The firewall crashed, we think it was a deliberate attack.” She laughed. I knew she couldn’t help it, that it didn’t mean much. She said I made it sound so melodramatic, like something orchestrated by Al Qaeda via satellite from a laptop in the Tora Bora. She didn’t obviously assume that I was lying.

“And you saved the world in your dressing gown?”

I tried, even then, to pull her down onto my lap, but there wasn’t enough room, and she bumped her hip against the edge of the desk. I pushed my chair back, and she stood up. The streetlamps outside daubed the attic skylights chemical orange. She switched on the lights, turning the panes to liquid mirrors, reflecting the room back on itself. In the sloping glass above her head I watched her notice that the photograph of her grandfather – the photograph in the cardboard frame that had been on the bookshelf in her father’s study all her life, until she brought it home and placed it on her side of the desk, beside her computer – was now on my side, beside my computer, my laptop. She picked it up and moved it back. I said: “Why would there even be a diary?”

Which she said made no sense at all, although she must have known it did. There had always been a diary.

“How could there not be one?”

I got up and walked across the attic room, dropped into the sofa.

Holly remained standing by the desk. “There’s always been a diary.”

I pulled a cushion onto my lap, leaned forward with my arms pressing it into my bare legs where the dressing gown hung open. “I’m just saying, Holly. There’s your grandfather, right? He’s a spy. The Germans invade and he burns all his papers. He’s on the run. And he starts writing everything down. Why? Why would he do that?”

She might have said: Because that’s what people do, because he did. We know he did. Instead she said, “I don’t know.”

“You don’t know?”

“I don’t know, Martin. Because it was interesting, maybe. Because he was hanging around with a lot of time on his hands and he was probably scared.”

“But he’s a spy, Holly. Isn’t he supposed to eat the fucking evidence?”

I was curled tight, squeezing the cushion on my lap, my arms wrapped hard around my legs. Wound tight. The way I used to be, the way I had been more and more, since I’d started to get involved again.

She said, “He worked in signals. He wasn’t James Bond.”

She said, “Martin? You should spend less time on the Internet.”

She came and sat next to me. She picked the remote up off the coffee table, turned on the television, and together we watched the news. We heard UN weapons inspectors say they could not be certain what had happened to all the weapons they’d catalogued in the past: the weapons might have been destroyed, but might not; they wanted more time to look. It was clear to us then, as it must have been to the inspectors, that there would be no more time. The news ended and Holly switched the television off.

I said, “They’re going to do it.”

“Of course they’re going to do it.”

“And then what?”

She shrugged. “Tea?”

She said she was going to bed, was I coming?

There was a diary. She had read the transcript. I had read the transcript.

She took her tea and a novel about Bombay and went to bed. I went back to the desk and was still there when I heard her switch off the bedroom light, still there when she left for work the following morning.

§

Somewhat against the odds, Aleks Overand had a good war.

A year before it started, he had volunteered to fight for Finland against the Soviet Union, an enemy that would soon become an ally. He was a little over one metre sixty-five, had flat feet and a hint of rickets; tests indicated possible undiagnosed diabetes. Even a volunteer army did not want him.

The letter was waiting on the table in the hall when he returned from court. “Pompous little beggar,” he said, when he had read it twice.

“Who, darling?”

“The under-secretary of stationery, or whatever he was. At the consulate. You’d think they’d be grateful.”

Kirsten told the children to sit down and watch out as the maid cautiously bore a vast iron pot into the room and placed it on the table, trailing an aroma that spoke of long preparation and rich ingredients.

“I told them if I couldn’t fight, I could at least drive a truck. I could run guns and bandages across the border.”

“You?” Elda laughed. Elda Overand was thirteen; already she wrote plays and read Russian novels. “A smuggler?”

“He can sail a boat,” Oskar spoke up in his father’s defence.

“It’s not really smuggling,” Overand said, in the voice he reserved for explaining the real world to his children, and to others less au fait with its complexities than he. “The government knows. They can’t admit it, of course, because we’re not at war, but they’ve told the police and the army to turn a blind eye.”

Oskar was ten, and wanted to be a lawyer like his father. He said, “Where do the guns come from, Pappa?”

“England, Oskar. Lee-Enfield rifles. Very reliable.”

Elda sighed and rolled her eyes. “Why do men love guns so much? Men who’ve never fired them?” (Prince Andrei was a soldier, it was true; but, despite his dream of shooting Napoleon, Pierre Bezukhov did not love guns: he loved Natasha.)

Her mother smiled but said, “That’s enough.” And, as the maid lifted the hot lid and released a cloud of steam, she added: “And I can’t say I’m sorry.”

She asked the maid to thank the housekeeper. The reindeer casserole was excellent.

In the year that followed, Aleks Overand became increasingly distracted and irritable.

No one was more surprised, Overand suspected, than the Finns themselves when Finland fought its vastly more powerful enemy to a standstill. (“You see,” Kirsten told her husband, “they didn’t need you.”) Everywhere else, however, war looked inevitable. He attended meetings where men, mostly less well dressed and less articulate than he, told him that the future lay in his own hands. That he was not powerless, but time was running out. He joined committees, signed letters. He learned to argue that only through rearmament and universal conscription – through a general mobilization of the whole people of Norway – was it possible to maintain neutrality and peace. (“Conscription? They still wouldn’t take you,” Elda said, and was sent up to her room.)

“Are you so determined to be killed?” Kirsten asked, when she believed the children were both asleep. “Do we make you so unhappy?”

“Our happiness is not the point,” Overand said. “There are greater questions at stake.”

Kirsten was not convinced.

“The question of freedom, of sovereignty,” Overand said, “is not about us.”

“Then whose freedom is it?” Kirsten asked.

His business did not suffer. Men still robbed and raped and murdered for all the old reasons, and the courts still tried most of them, but Overand felt his pleas and legal arguments were more and more beside the point. What good were depositions when all of this was about to be swept away?

Could no one else see that?