8,39 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Salt

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

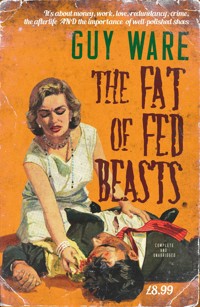

'Fleshing out the shadowy metaphysical hints of Beckett's novels, this intellectual romp is the best debut I have read in years' Nicholas Lezard, The Guardian Monday lunchtime: a bank is being robbed. The gunmen tell everyone to get down on the floor, but an old man refuses. Behind him in the queue is Rada Kalenkova, an investigator for the Office of Assessment, recording everything she sees. Shots are fired and a woman is killed. Or maybe two. But Rada ignores the murders and pursues the old man instead. Nothing about the robbery or the putative killings makes sense. The robbers might be police. The bank manager denies anyone was hurt, despite the blood on the walls. Every subsequent enquiry leads towards Edward Likker, a renowned fixer. But Likker is dead. The Fat of Fed Beasts is an ambitious literary mix of existential uncertainty, murder, bureaucracy, unreliable father figures and disaffected policemen. It asks why we do what we do, whether it matters, and what, if anything, our lives are worth. And it's funny. 'Ware has an uncluttered prose style and a willingness to stretch the boundaries of fiction. His sensibility is finely tuned to those grey areas of experience where identities shift, where people forget who they really are. No other writer springs to mind as a ready comparison to Ware: already he has defined a unique thematic territory.' Aiden O'Reilly, The Short Review

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

The Fat of Fed Beasts

‘Ware has an uncluttered prose style and a willingness to stretch the boundaries of fiction. His sensibility is finely tuned to those grey areas of experience where identities shift, where people forget who they really are. No other writer springs to mind as a ready comparison to Ware: already he has defined a unique thematic territory.’ —AIDEN O’REILLY, The Short Review

Monday lunchtime: a bank is being robbed. The gunmen tell everyone to get down on the floor, but an old man refuses. Behind him in the queue is Rada Kalenkova, an investigator for the Office of Assessment, recording everything she sees. Shots are fired and a woman is killed. Or maybe two. But Rada ignores the murders and pursues the old man instead.

Nothing about the robbery or the putative killings makes sense. The robbers might be police. The bank manager denies anyone was hurt, despite the blood on the walls. Every subsequent enquiry leads towards Edward Likker, a renowned fixer. But Likker is dead.

The Fat of Fed Beastsis an ambitious literary mix of existential uncertainty, murder, bureaucracy, unreliable father figures and disaffected policemen. It asks why we do what we do, whether it matters, and what, if anything, our lives are worth. And it’s funny.

Praise for Guy Ware

‘In Ware’s fiction, the outside world, outside society, outside agencies, are the “us” bearing down on the “you”. Characters are isolated until their own shaky identity is corrupted and challenged. Ware asks how we can hold onto ourselves when what happens without is so random and fraught with possibility.’ —STUART EVERS,The Independent

‘You Have 24 Hours To Love Usis a clever, playfully uncanny debut collection that has left me looking forward to more of Guy Ware’s writing.’ —MAIA NIKITINABookmunch

The Fat of Fed Beasts

Guy Ware’s stories have appeared online, in magazines and in numerous anthologies. His collection, You Have 24 Hours to Love Us (Comma, 2012), was longlisted for both the Frank O’Connor International Award and the Edge Hill Short Story prizes. ‘Hostage’ was subsequently included in the Best British Short Stories 2013 (Salt). The Fat of Fed Beasts is the first novel he hasn’t put in a drawer and left there.

Published by Salt Publishing Ltd

12 Norwich Road, Cromer, Norfolk NR27 0AX

All rights reserved

Copyright © Guy Ware,2015

The right ofGuy Wareto be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with Section 77 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Salt Publishing.

Salt Publishing 2015

Created by Salt Publishing Ltd

This book is sold subject to the conditions that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out,or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

ISBN 978-1-78463-047-8 electronic

For Sophy And for Frank and Rebecca

“What reinforcement we may gain from hope,

If not, what resolution from despair.”

MILTON, Paradise Lost

“I have often thought upon death, and I find it the least of all evils.”

BACON, An Essay on Death

1

THE OFFICE ISnot empty, or it would not be an office. There are desks and chairs and computers and some paperwork that hasn’t been filed, and there are coffee mugs, some of them clean. On D’s desk, there are two or three self-help books for managers, which D isn’t. Plus he’s beyond help.

But there are no people.

I am here.

There are no other people. Work is for once not hell. Which is ironic – or a coincidence, anyway – given what we do here. I should take advantage.

Not empty, then. But quiet. I am not working. I do not disturb the air around me. But the computers hum and trains still rumble past our third-floor window.

Peaceful, though: an unanticipated bonus in the middle of a working day. It is Monday, so Theo will be at Riverside House. Perhaps. We believe that is where he spends each Monday morning. Rada went for an early lunch; she had to go to the bank, she said. D has been working at home. This is not like D, who has not been himself recently. Just as stupid, obviously, but more focused, somehow. He is up to something. Whatever it is, it will be drivel.

The windows in this office do not open.

I should make a telephone call.

Specifically, I should call Gina Spence. Theo will be expecting progress – you would think, at his age, he would know better – but I have nothing to report. I have not spoken to her. It’s not the suicide that’s the problem. I don’t mind suicide; you might even say it’s my speciality. But some suicides have mothers who are themselves not dead.

I roll a cigarette, but do not light it, even though the office is empty.

Unwelcome sunshine smears the room. My desk is sticky with it. For a moment I wish I could open the window. But I know it is hotter outside than it is in here, and more humid. There is no breeze. It is June but seems to think it’s August. I cannot open the windows because the windows in this office do not open: the office is air-conditioned; the air conditioning does not work. The meeting room this afternoon will be unbearable.

(We will bear it.)

I realise I am squandering the unanticipated tranquility of an almost empty office. Soon Rada will return from the bank. D will foul the already fetid air with testosterone and stupidity.

I should ring Gina Spence, but I won’t, not today. I have written up two reports – one up; one down – and that will suffice. Someone commits suicide every thirty-six seconds. This is a job, not a vocation.

For the Ancient Egyptians the heart was the seat of the soul; when you died it was tested in the scales of Maat. If your heart weighed no more than a feather, you made it into the fields of peace. The heart is a meaty organ: tough, dense and muscular, the size of a clenched fist. An unequal deal, then? A long shot? Apparently not. There is no Egyptian Book of the Dead in which the applicant fails; crocodile-headed Ammut waits to eat the hearts in vain; Thoth, who invented writing, records the same verdict every time. Our system is more realistic. Or at least less certain.

Rada has not yet returned from the bank when D arrives, wanting to talk to me. He does not want to talk to me in particular – indeed, he would probably prefer to talk to anyone but me – but I am the one here. Before he can begin I raise the telephone to my ear. With my free hand I signal that I am occupied. Then I pretend to listen. D walks over to my desk anyway. He hovers. He does not sit down at his own desk six feet away and I hate him more than ever. He has thick black wavy hair that falls forward over his eyes and he pushes it back all the time. He could just get it cut. He tosses something small up into the air and catches it. Spiritually, he is whistling. I nod and say Uh-huh into the silent phone. I roll my eyes and pretend to slit my throat as if to indicate that my interlocutor is boring me to death. D tosses whatever it is into the air again – it is a memory stick, I can see that now – and catches it. He does not leave my desk. I accept the inevitable. I put my hand over the mouthpiece and say: Mothers. Fuck ’em.

D nods, says: Dads are just as bad.

I had not expected this. I wonder if he is talking about his own father, which would be unlike D. I probe: Worse, maybe?

Yeah. Quieter, but way worse.

Way worse? What has D been reading now? In my disgust I forget to pretend to say goodbye and just hang up.

D asks me who it was.

No one.

D looks confused. He can’t work out if I’m telling the truth (which of course I am), or if this is a joke at his expense.

He flips the memory stick between his fingers, attempting to roll it around his knuckles, but drops it. His hair is sleek, like oil on a stranded seabird. As he bends down to retrieve his toy I see traces of some unguent in the roots at his parting. He has come from the shower at the gym. I despise him. But my day is clearly ruined, anyway, so I ask him what is on the memory stick.

He smiles, savouring the moment.

He says, My future.

It’s empty, then?

Ha-ha. It’s Likker.

I know who Edward Likker is – was. I say, What kind of a name is Likker?

He’s my ticket to glory.

D says this, in those words. How old Kalenkov spawned both Rada and this fart in a suit defeats me.

He says, You want to know why?

I am all ears.

D looks around, as if the office might have rearranged itself since Friday, then walks over to the flipchart stand in the corner. He drags it towards my desk, the extendable legs catching in the carpet. It leans towards him like a teenage drunk and the fat marker pens slide onto the floor. He straightens the stand, tightens the screws and bends down to recover the markers. His suit jacket rides up and I am presented with his stairmastered arse in broad chalkstripe. Truly the Lord is bountiful. He tests the pens until he finds one that hasn’t dried up. It is green. He sketches a two-by-two matrix and writes “Complexity” along the bottom axis, “Value” up the side. He writes “Low” at the point of origin, and “High” at the tip of each axis.

I watch, a familiar weariness gathering in my bones. I say, How are you measuring value?

There’s a formula.

D flips the matrix over the back of the stand and begins to write again on a blank sheet. He runs out of space and has to go onto the sheet beneath. He flips back, tears off a sheet and holds it up next to the stand so I can read the whole thing:

And this helps how?

With his free hand, D points to each element of the formula in turn. The lifetime value of a customer equals the discounted gross contribution they make minus the discounted cost of retention.

Value to whom, D?

To the company, of course. OK, we’re not a company. We don’t have customers, as such. But surely you can see how it applies?

I can – it’s obvious when you think about it – but so what? He’s still not getting Theo’s job.

I say, So where does Edward Likker rate?

D grins like a hyena.

Likker’s perfect.

I know what he means. What he means is not perfect at all. He means complex. High value. He means a great white dead whale, amongst dead minnows. A death worthy of the scales of Maat. For a moment I am almost jealous. Then I remember this is D and he will fuck it up.

2

THE MAN INfront of me who would not do as he was told and get down on the fucking floor when everybody else got down on the fucking floor moved slowly; he didn’t always seem to notice when somebody had finished and stepped away from the cash machine and the queue shuffled one step forward. There would be a pause. A gap would open up and I would feel the pressure growing and the impatience of the people waiting behind me. I felt it myself, the desire to speak up, to tell the old man to get a move on, even though his hesitations made no real difference to the time it would take us all to get our money. I thought about saying something, but nobody speaks to another person in a queue. To be clear, this was not out on the street where sometimes you have to pause and allow a gap to open up to make space for pedestrians who are not waiting for the cash machine or having anything to do with the bank or building society, or whatever, but are just passing along the pavement to somewhere else. It was indoors in a sort of open-plan foyer area of the bank where there were seven machines you could use to withdraw cash or to pay in cash, or cheques, with a queue at each, and there were no actual cashiers. It was cool in the bank; after entering from the humid street, customers would pause to adjust. Some of us would sigh, or surreptitiously adjust our clothes, allowing the refrigerated air to dry our skin. There were two bank employees in a sort of low-key uniform standing to the side of the queues waiting to help anyone who had trouble with the machines, plus one hovering near the door, a chubby woman with a neat blonde bob who had said hello to me when I entered the bank maybe six minutes earlier.

It is hot now in the meeting room, which is up on the fourth floor and has a low ceiling. It is just after four p.m., and the heat has been building up all day. We cannot open the windows because the windows do not open in this building; there is air-conditioning, but the air-conditioning does not work. It is June and there will most likely be a thunderstorm before long; since lunchtime, since the events I am reporting, the sky has turned a sleek mackerel grey. If we could open the windows, the noise of the trains, which pass just below us on elevated tracks, would be impossibly distracting. There are four of us in the room, seated around an oval mahogany table. The table is richly polished and, from where I am sitting, facing the window, the sunlight turns its surface liquid. Briefly, I imagine my crisp pile of closely-typed pages separating and floating on the table like lily-pads.

The man was old, I could tell, even from behind. He had probably been quite tall once, but he was now a little stooped, leaning on a walking stick, his head pointing somewhat forward from his shoulders, not straight up, and the skin above the collar of his shirt was dry and yellow; the hair above the skin was white and clipped short against his neck.

At this point in my report, I stop reading to acknowledge that there is some question, which might become relevant later, in the event of any reprimand or even disciplinary action being deemed appropriate, as to whether I was technically off duty, or not. I was at work, in the sense that it was a working day. I had spent the morning in the office listening to the kind of maddening and distracting fossicking about Alex chooses to do when he should be researching a claim or typing a report or whatever but is actually too unfocussed to stay on task for more than five minutes, without spinning his chair or throwing balled-up timesheets at his computer or trying to start a conversation with me. I took lunch earlier than usual, partly so that I could go to the bank for some cash and to pay in the cheque Gary’s mother sent as a present for Matthew, who will be eight at the weekend. I had thought it possible that Gary’s mother was the only person left in the world to still use cheques, but the presence of machines there in the bank this morning, machines which existed only for the purpose of depositing cheques, suggests otherwise. As there were no actual cashiers, I realised I was going to have to queue twice, for separate machines, and decided to get cash for myself and for Matthew first on the grounds that the queues for cash withdrawal were longer and I prefer to get the queuing over with as quickly as I possibly can.

Theo says not to think about reprimands right now. I should just concentrate on my report. The right now merely confirms my anxiety. I am in trouble.

The old man with the white hair and yellow skin and the walking stick had reached the head of my queue and, after a brief hesitation, had moved right up to the machine, and was hunting through his wallet for his card, when I became aware of an increase in noise and a sense of urgent or flustered movement around us. I turned and noticed that there were now three men in the bank who had not been there when I entered seven minutes earlier, and who had guns. The men were dressed in black; they wore Kevlar stab-proof vests and artificial fibre balaclava helmets. One of the men was short; strands of reddish hair or whiskers curled around the edges of his balaclava. Two of the guns were pistols – Beretta 8000-series Cougar semi-automatics – and the third was a much larger sub-machine gun. The men were shouting that everyone should do what they were told and get down on the fucking floor, which I did.

One of the men pushed some sort of stick through the polished aluminium handles of the double entrance doors. The stick was about a metre long and had a shorter element jutting out at right angles near the end, as if it were a handle; the whole thing may, in fact, have been an extendable sidearm baton of the type used by police forces to control situations of perceived or anticipated civil disorder. The handle of the baton caught on the handle of the door and effectively prevented anyone from entering the bank from the street. At this point one of the men said they were police, although this was not the first thing they had said and I wasn’t sure I believed it, or not, but I also wasn’t sure it made any difference to my getting down onto the floor in any case, or not, given that they were armed as I have described. The floor was covered in a kind of thick linoleum in the bank’s corporate colours and was mostly red. The air-conditioning in the bank was so effective that even today, in this weather, the linoleum felt cool against my cheek. I was quite prepared to observe, and mentally to record any detail that might later prove helpful, or relevant, to whatever claim or claims might arise, but I was not going to not do what I was told by men with guns, even or perhaps especially if those men were not policemen. Neither were the bank employees (who were no doubt governed by bank protocol and training for just such an event, and would have practised) or any of the other customers, except the old man in front of me, who, having finally found his card and inserted it into the machine, ignored the shouting and began entering his Personal Identification Number. I thought the man might be deaf – although he would have to have been profoundly deaf not to have heard anything of the commotion behind him – and perhaps not blessed with the best peripheral vision, or to have been blind, even, although his stick wasn’t white and there was no sign of a dog or anything, because most people, I thought, even if they were concentrating on pressing the right buttons and maybe making the right choices on the touch screen, would notice when everyone around them, which was perhaps a dozen or fifteen people, not including the men with guns, dropped suddenly to the floor.

One of the men shouted again and pointed his semi-automatic pistol at roughly the point where my head had been before I knelt, and then lay down, and I thought the old man was going to get shot. I recall thinking it would be a shame and something of a waste and a tragedy for a person to get shot just because he was deaf and maybe didn’t have the best peripheral vision. I reached out my right hand. From where I was lying, face down on the linoleum, I could just touch the old man’s foot. He was wearing brogues in thick, tan leather with the depth of shine that I knew, from having watched my father clean his shoes, and mine and, later, D’s, every Sunday evening until I was fourteen years old, came only as a result of repeated polishing over many years. I pinched the turn-up of his right trouser leg between my first and second fingers – I could not quite reach it with my thumb to get a better grip – and tugged, as best I could, to attract his attention and alert him to the danger he was in. He lifted his foot without turning, and shook it, as if shooing away a fly. When he put it down again, the heel – which I noticed was rubber, although the shoe had a leather half sole which was nearly new, or at least not worn – landed heavily on the first two joints of my index and middle fingers, and I could not help shouting out, even though I was trying not to, on account of not wanting to attract the attention of the men with guns, and possibly get shot.

When I shouted the old man, who was evidently not deaf, turned, and at the same time bent down towards me. It is still also possible that he was deaf, and, feeling something under his heel – a pen, or even a wallet, perhaps – had turned and simultaneously bent down to see what it was that he might be stepping on. Whether it was the sound of me shouting or the sensation of obstruction, or some combination of the two, he turned and bent at precisely the moment when the man with the gun pulled the trigger. I thought it was likely that the old man still hadn’t realised what was going on around him and I closed my eyes, involuntarily.

Here I lay the page I’ve just finished face down on the pile to my right and, before picking the next page from the larger pile in front of me, I take a moment to point out that although I am a trained observer, I was not on duty. Even if I had been, I would not have seen everything because the decision to close my eyes was not conscious; it would not have been a dereliction of duty, even if I had been on duty, officially, because my unconscious mind anticipated the horror and traumatic images it would not be able to eradicate easily and took over control from my trained, conscious mind, despite the training, and I doubt that, honestly, any of you would have done any differently. Theo, perhaps, could have kept his eyes open; but not you, D, and not Alex.

After which I continue.

When he turned around I saw that I had allowed myself, from the stoop and the slowness in moving forward and perhaps even the idea that he might be deaf or in some way visually impaired, to generate an image in my own mind of a man older than he really was, which was perhaps, I now saw, only mid-sixties, seventy maximum, about the same age my father would have been. I observed this before I closed my eyes and consequently missed the moment when the bullet, as a result of his bending down towards me at the same moment that he turned, missed his face by what could only have been millimetres, judging from the angle of fire I observed when I reopened my eyes, by which time the bullet had passed through a laminated “Cash Withdrawals” sign, through the plaster board and red-painted skim wall to which the sign was affixed, presumably by some sort of industrial polychloroprene adhesive, and through into the office or meeting room or interview room where it must have hit a person I judged from the pitch of the subsequent screams to be a woman, possibly a female bank employee who was in the office or interview room at the time. This woman had not been in the public area of the bank since the entry of the gunmen, and so would obviously not have seen them or heard the instruction to get down on the floor – or, more likely, given the flimsiness of the dividing wall – she may have heard the instruction indistinctly, or may have heard it clearly but simply not understood it or realised that it applied to her, given that she had no visual or other context in which to interpret the instruction as a threat to her own well-being, and was therefore still upright, her head at approximately the same altitude as that of the old (but not ancient) man who I could now see had once been tall but had lost an inch or two to age and gravity, and was thus – the woman – in the (albeit probably deflected) line of fire for no reason other than sheer bad luck/incomprehension.

Jesus, Sis, can we just cut to the chase?

D has a memory stick in his hand. He has been turning it over and over, tapping one end then the other on the thick varnish of the meeting room table. He would have started off trying to listen, I know, albeit not very hard and not for very long. After a while his concentration would have drifted; his eyes would have lost focus and I know that by now he will be timing the gaps between trains, again, counting seconds under his breath. Our meeting room is in a building up by where the railway crosses over into the station. The sound-proofing is good and you can’t really hear the trains through the sealed windows, although you can see the aluminium frames vibrate slightly, if you look, and especially if, as now, there is a fly caught in a web in the top right hand corner of the window. As usual, I have chosen the chair facing the windows. I do this to reduce the potential for distraction in my fellow team members, D especially. While I am confident of my own capacity to concentrate, my brother has always lacked focus; he has always been unable to stay truly present – in a room, or in a conversation – even when it is clearly in his own interest to do so. Right now, he will have given up on my report, and – since Theo has recently confirmed that he will not be with us much longer – D lacks even the primal motivation of not aggravating the boss too much that seems, up to now, to have restrained more overt displays of dissatisfaction and boredom.

D says, I mean, this only happened this morning.

He is speaking to Theo, not to me. Theo says, What is your point, D?

D makes a noise like there is something stuck a long way up his sinuses. He says, My sister can’t go out for a pint of fucking milk without falling over something. She can’t go to the bank like anyone else and get some cash – pay in a cheque, whatever – without running into three armed men and a couple of murders.

I have mentioned only one possible murder so far, and that not conclusive. Theo speaks mildly, in a tone that, whether he knows it or not, is guaranteed to provoke D. I’m certain Theo knows what he is doing.

D says, That’s my point! She’s been reading for, what, eight minutes? EIGHT minutes, and we’re maybe ONE minute into the actual event. It was only this morning. D turns away from Theo, back to face me. When do you even get time to type all this shit?

Theo has taught me not to allow myself to be distracted. I say, The details are important, D. We all know that.

OK, but Jesus, Sis. You’re face down on the lino. Some civilian’s dead and you’re waiting for what I’m assuming here is the subject to get shot in the face. Right? Can you not just tell us: is the old guy in or not?

It is Monday and despite the heat Theo is wearing the herringbone suit. He also has on a white poplin shirt and an anonymous, but possibly regimental, tie with a thin green forty-five degree stripe on a broader red stripe on a darker green background. He has trimmed his beard, which is silver. Not long after D started, Theo took him aside and gave him the name of the tailor who had made this suit; D wrote it down but hadn’t actually visited. Recently D tried calling Theo OMT, short for Old Man Theo. Not to his face, obviously; but in the office, when we were supposed to be working. It was OK in emails or texts, but when you said it aloud even D had to admit it wasn’t that snappy and it hasn’t stuck. Theo would be about the same age as the older man in my report, the man in the bank.

Theo says, Allow Rada to report the incident in her own manner. He always says that. We won’t know what’s important and what isn’t until she has finished. God is in the details.

D knows this; we all know this, but D is still impatient. Can’t we just take it from the point where the old deaf guy gets shot and dies and turns out to be someone we’re interested in? Please, Sis?

I hate it when he calls me Sis, especially at work. He knows this, of course, which is why he does it. We have discussed this, at home, more than once. At work, I always tell him, we should be professional. D generally says that’s a joke, on account of how he’s the one trying to drag the place into the twenty-first century. The memory stick he has been fiddling with contains his position paper on calculating Lifetime Value, which, according to the written agenda Theo circulated at the start of the meeting, D will present when we’re through with the reports. He must know that interrupting, and calling me Sis, is not going to make me get through my report any more quickly. It never has.

Theo nods and I lift a new page up in front of my face and begin reading again.

I saw the man who had fired his gun take his eyes for a moment off the older man who was still standing, who in fact was straightening up from where he had been bending down to look at me. I saw the gunman’s eyes beneath the balaclava helmet; they were grey and looked clouded. The older man must have realised by now that something out of the ordinary and severely threatening to himself and other people was going on, but he did nothing, other than to straighten up. He stood, apparently waiting for the man with the gun to turn back to him and resume his threats. It occurred to me then that perhaps the older man was neither deaf nor visually impaired and might not have been absorbed, in particular, in correctly punching in his Personal Identification Number, but was perhaps more of the absent-minded professor-type with fully working senses that were nonetheless overwhelmed (in terms of neurological stimulation and the kind of messages capable of reaching and attracting the attention of his conscious mind) by the contemplation of some abstruse and potentially world-changing mathematical formula or theorem or whatnot, and that was why he seemed not to have noticed what was going on around him and to get down on the floor like everybody else. But it then occurred to me that if that – the absent-minded professor thing – accounted for the older man’s initial lack of awareness, or response, at least, to what was going on and being said, or shouted, it would not adequately explain why, when he had turned around and could plainly see the man with a gun no more than six feet away from him, and could see the people around him, including me, lying for the most part face down on the floor, and must have heard the shot that had missed his face by no more than millimetres, and could, like the rest of us, hear the continuous or rather pullulating screams emanating from behind the partition wall through which the bullet had passed, why, given all of that, he did nothing but stand and wait. It must have been obvious that he was caught up in a robbery or some kind of siege or even terrorist situation. At this point I had not been able conclusively to dismiss the claim made by one of the men with guns that they were in fact policemen, although none of them had actually shouted Police! or even Armed Police! as their first action on entering the bank with guns in the way that I imagine, on the basis of watching a number of films and TV shows, they would have done if they had in fact been policemen, or at least would have been supposed to do by protocol and legally-enforceable guidance, although I’m pretty sure that in some of the films or TV shows I’ve seen the failure of the police to shout Police! or Armed Police! was the subject of much discussion and dispute amongst the various characters – who often had differing memories and interpretations of the events, not to mention differing motives and interests – and was, in fact, the principal plot-point driving the drama, and it was likely that such dramas were based to some extent on reality and that such an omission might occur also in the excitement of real-life events. It was therefore still possible that the older professorial man might have believed himself to be involved in a robbery or siege or terrorist situation in the process of being interrupted and thwarted by the forces of law and order. But even if this were the case, it still did not explain adequately why, when faced by a man in a balaclava helmet with a gun he was obviously prepared to fire and who had told him to get down on the floor like everybody else, why the older man didn’t, but stood there, apparently oblivious to the gravity of the situation, the only person in the public area of the bank without a gun still upright, waiting for the man who had fired his gun and missed him by millimetres to re-focus his attention, waiting, in fact, for all the world like a professor who has asked his seminar students a fundamental question to which he of course knows the answer, or at least an answer, but has no intention of letting his students off the hook by answering before at least one of them has worked it out for himself. Waiting, in other words, mildly, as if to see what would happen next.