9,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

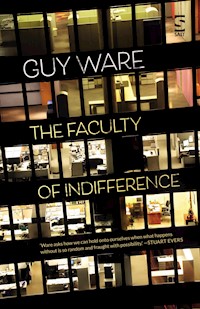

- Herausgeber: Salt

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

Robert Exley works for the Faculty: he spends his life making sure that nothing ever happens. In counter-terrorism, that's your job. But something's going on. His wife, Mary, also worked at the Faculty. She's been dead for years, but somehow she's never far away. His father worked there, too, and spent a lifetime on a mountaintop watching out for signals, hoping not to see them. His bookish teenage son, Stephen, writes an encrypted journal Exley feels obliged to decode, to read the things they cannot talk about. Lately it's all about the boy's grandfather. And even if it's mostly fiction, Exley knows there's only one end to that story. The Faculty of Indifference is a comedy about counter-terrorism, torture, boredom, suicide and death by natural causes. Trapped between the memory of an intolerable past and the anticipation of so much worse to come, Exley finds there's nothing he can do but live.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

THE FACULTY OF INDIFFERENCE

by

Guy Ware

SYNOPSIS

This is what a bad day looks like: a day when something happens.

Robert Exley works for the Faculty: he spends his life making sure that nothing ever happens. In counter-terrorism, that’s your job.

His wife worked there, too. She’s been dead for years, but somehow she’s never far away. Now their bookish son is leaving home. He writes an encrypted journal Exley feels obliged to decode, to read the things they cannot talk about.

When Exley takes on a colleague’s case, it leads to a flat full of explosives, guns and cash. The trouble is, it’s the wrong flat. And when Exley finds a man in an orange jumpsuit shackled to the floor deep beneath the Faculty’s offices, everything he thinks he knows turns inside out.

Mixing Beckett and St Augustine, prison diaries, Japanese Go and Greek tragedy, The Faculty of Indifference is a profoundly black comedy about torture, boredom, suicide and love. Trapped in the moment between an intolerable past and so much worse to come, Exley finds there’s nothing he can do but live.

PRAISE FOR PREVIOUS WORK

‘Fleshing out the shadowy metaphysical hints of Beckett’s novels, this intellectual romp is the best debut I have read in years.’ —NICHOLAS LEZARD, The Guardian

‘The staff of the office are revealed as gatekeepers to the afterlife, setting up a neat reversal in which determining the resting place of recently departed souls is treated like any normal job – employees rock up late and use work computers for their own projects – while mundane tasks, such as making couscous salad, are addressed with scholastic intensity.’ —SAM KITCHENER, The Literary Review

‘About halfway through the book, Ware sheds light on the mysterious title. The fed beasts are from the Book of Isiah, one of those bloodthirsty sections about offerings and livestock slaughter and so on. But Ware’s disdain for the corporate world’s overfed beasts is apparent but rendered with enough empathy and humour that it does not overbear this delightful book.’ —JUDITH SULLIVAN, SHOTS Crime & Thriller Ezine

‘Absent, slippery or suspect ‘facts’ are central to this unapologetically knotty novel.’ —STEPHANIE CROSS, Daily Mail

‘Stories passed down through generations can shape a family but are also subject to the distorting lenses of memory and perspective. Author Guy Ware’s grandfather worked for MI6, escaped from Norway in 1940 and kept a diary, but his new book Reconciliation (Salt, £8.99) is fiction. It follows Holly Stanton, whose grandfather was a spy and happened to be in Norway when the Germans invaded, and who kept a diary. It’s a well-known family story but it only becomes tangible to Holly when she finally gets her hands on the diary. Moving between various real-life events, each laced with errors and lies, Ware demonstrates to the reader how easily we can be misled as he explores the ethics of storytelling in this wartime thriller.’ —ANTONIA CHARLESWORTH, Big Issue North

‘This ingenious novel succeeds in being both a highly readable story of second world war derring-do and its aftermath and a clever Celtic knot of a puzzle about writing itself… Just who is telling this story? There are different narrators, but verbal tripwires indicate that all is not as it seems: impossible echoes from one person’s account to the next alert us to the, yes, fictional nature of what we are being drawn into and pull us up short. The complexity of who saw what and wrote what is maddening but also exhilarating, and very funny in places.’ —JANE HOUSHAM, The Guardian

The Faculty of Indifference

Guy Wareis the author of more than thirty short stories, including the collection,You Have 24 Hours to Love Us, and three novels. He won the London Short Story Prize 2018 and was longlisted for the Galley Beggars Story Prize 2019.The Fat of Fed Beasts, was chosen as a ‘Paperback of the year’ by Nick Lezard in theGuardian, and described as “Brilliant . . . the best debut novel I have read in years.”Reconciliationwas described byThe Literary Reviewas “memorable and inventive” and by theGuardianas “exhilarating, and very funny”. Guy lives with his family in New Cross, South London.

Published by Salt Publishing Ltd

12 Norwich Road, Cromer, Norfolk NR27 0AX

All rights reserved

Copyright © Guy Ware,2019

The right ofGuy Wareto be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with Section 77 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Salt Publishing.

Salt Publishing 2019

Created by Salt Publishing Ltd

This book is sold subject to the conditions that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out,or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

ISBN 978-1-78463-177-2 electronic

For Sophy

And if you have lived one day, you have seen all: one day is equal to all other days. There is no other light, there is no other night.

—MICHEL EYQUEM DE MONTAIGNE

FOUR OR FIVE YEARS AGO

FOUR

The same, only more so

“How was ittoday?”

Stephen asked that all the time, four or five years ago. Not all the time, obviously. Not all day; not even every day, but most days – most working days – when I got home from the office or, more often, from the pub we drank in when we left the office. He’d ask how it had been. Sometimes, it’s true, I’d come home from somewhere else. The office of a partner agency, perhaps, or an investigation site: the scene of an explosion, say, or a shooting. On such occasions, however, the time of my return would be less predictable, and Stephen would be less likely to ask how my day had been, because he might not be in the kitchen, making dinner, or in the living room watching TV, but upstairs, in his own room, working, or writing his journal. Then he might call out hello, but nothing else. Or he might say my dinner was in the microwave (if I were late) or that he’d be cooking soon (if I were early). The day I was describing, though, four or five years ago, he’d asked how it had been, and the following day I said – to Simmons and Leach, not to Stephen – that he sounded like my mother, or Mary.

“That’s nice,” Simmons said. She liked to give the impression that she saw the best in everyone (which was difficult, sometimes, and probably a disadvantage, in our profession). I said he was my son, for pity’s sake. He was not supposed to be solicitous. There’d be time enough for all that when I was too old to tie my own shoelaces. Simmons said it was nice he showed an interest. But we all knew where that might lead. I told them I’d said, How was what? and he’d said: Work, what else could it be?

Leach put down his glass. “Hang on a sec . . . Did you say that or did he?”

“Say what?”

“What you said. About what else it could be.”

I looked at Leach – something I try not to do too often. “You want to know if I said what I said ten seconds ago?”

He said I knew what he meant, which of course I did, so I said that I’d said that. Which, if he’d thought about it, wouldn’t have left him any the wiser.

Simmons ignored him. She said her daughter, Nicola, didn’t even know what she did for a living, much less ask. She said of course she didn’t know, but, well, we knew what she meant, and of course we did, it was the same for all of us. She said MydaughterNicola, as if it were one word.

This conversation, if it is not already obvious, took place in a pub, after work. The pub in question was the Butcher’s Arms, just across the road from the Faculty, from work – so we couldn’t talk about work, because you never knew who else would be there – and just across another road from the railway station, so we could each drink until two or three minutes before our respective trains were due to leave; in other words, it was pretty much perfect, despite its many faults. The place was generally crowded, and smelled less of beer than of the damp, gently poaching fug of nicotine-impregnated overcoats; of acid sweat and twelve-hour-old deodorant; and of cooking, it being the kind of pub that sold food, after a fashion. I suppose they had to make a living. Even at five thirty, when nobody was eating anything more adventurous than crisps, the scent of a crowd dressed for a bitter cold December but crammed into an overheated locker room still carried a subtle note of grilled meat, chips and fake Thai curry. It was a pub none of us would ever have drunk in, not by choice, had it not been a mere grenade’s throw from both the office and the railway station. We were not there for the company.

It hadn’t been a good day – either the day before, when Stephen asked, or that day itself, the day we were in the pub discussing the fact that he had asked – not a day that any of us would call a good day (that would be too much to ask), but it hadn’t been a bad day, either. No one had fired a mortar into a cinema; no one had worn a suicide vest to a crowded supermarket; or if they had, it hadn’t worked. Which, while not exactly the same thing, was good enough to be going on with.

There was still time, of course. The night was yet young.

Leach said, “So what did you say?”

“What I always say.”

“Which is?”

“If I told you that, I’d have to kill you.”

Simmons said she – by which she meant herdaughterNicola – was all over her dad, but that was girls for you. Never mind that it was Simmons who paid for all the riding lessons and the field trips to fucking Mauritius.

Leach, a beat behind as usual, said: “Do you mean kill me, or him?”

When I got home, he said it again – How had my day been? – and I said: “Don’t.” He said he was only asking, trying to be empathetic. I asked if they taught him that at school these days.

He said, “I made spaghetti.”

“At school?”

“For dinner.”

I said I was sorry, and it wasn’t that far from the truth.

He was a decent cook, as it happens, for a boy of seventeen.

Work, meanwhile, had been what it always was: intolerable. When anyone else asked, if I didn’t just say I couldn’t say because then I’d have to kill them, I would say: You don’t want to know. But, really, by then – when I’d already been at the Faculty for twenty years or so – no one but Stephen ever asked, because the only other people I talked to were at work (Simmons, Leach, Butler) and they already knew. In the past – ten, fifteen years ago, when Mary was around – there’d been people who persisted, out of misplaced politeness, perhaps. She would invite them to our house, or be invited to theirs. I’d go with her and they’d ask and I would say, no, really, you don’t, you really do not want to know.

Intolerable? I’d tolerated it.

While we ate, Stephen said it had happened again. I didn’t need to ask – and wouldn’t be able to do anything, or even say anything, that would help – but I asked him anyway what had happened again. It gave the semblance of conversation.

“The knocking.”

I said, “The same as before?”

He nodded. He said it had been the same, only more so.

Ours was a terraced house and sometimes – on one side in particular, where the chimneys were back-to-back and fed the same flues – you could hear the neighbours breathe. One night, years ago – it must have been – Mary and I had been in bed. She’d rolled off me, and I’d rolled too, and laid my arm across her belly, my face against her shoulder, and watched her breast rise and fall as her breath slowly returned to normal. She reached for her cigarettes, and in that perfect moment we both heard the man next door, in his bedroom, laugh and say, “See?” and his wife say, “No.” We hadn’t known whether they were talking about us or them, but we’d both laughed, too, laughed uncontrollably, until Mary forced herself to stop and put her hand over my mouth and rolled back on top of me. I knew, too, that soon, in less than two years, Stephen would leave. He would go away to university and I’d have the house to myself with only the sound of the television, the rattling of cutlery in the drawer as I did the washing up, the neighbours coughing, or plugging and unplugging electrical appliances, but in the meantime I had not once heard the knocking Stephen regularly complained about.

I said, “More? Do you mean louder?”

He said he meant more, going on for longer, but otherwise just the same. Except that it was never the same, no pattern or repetition, it was just noise.

After dinner we watched the news together. I sat in the armchair, as usual, while Stephen lay across the sofa with his feet – which were already bigger than mine, and bony, and seemed, to be honest, like the feet of some cave-dwelling giant – hanging over one arm of the sofa, the one nearest to me, his head resting on the other. There were hairs growing from his big toes, which did not seem possible, but there they were. After a few minutes, Stephen twitched and reached out for a book on the coffee table, riffled through the pages and put it down again. There was not much in the news. Obviously there were things not in the news, by which I mean things left out of the news, things that I could have told him about, if he were interested. If he had asked about my work today (and every other day) because he wanted to know – not just because he wanted to ask, or rather, to have asked and for me not to have replied – and if it had been possible for me to tell him anything. Things about the threat level, for example: why it was what it was. Instead, I asked what he was reading. Not because I wanted to know, of course, but because I wanted to have asked. He asked about my work, when he shouldn’t – that wasn’t what teenaged boys were supposed to do, but he did it anyway – and I didn’t answer. I asked what he was reading because that was what I was supposed to do. I was his father; he was my son. It was my job, my function, to take an interest in his life, or at least to show an interest. He picked up the book again and tossed it across the room to me, inaccurately. I failed to make the catch and the slim paperback – less than two hundred pages, I guessed – hit the wall behind me. I said he shouldn’t treat books like that. I picked it up from the floor: Marcus Aurelius’ Meditations. If I opened the cover, I would find ‘Mary Walsingham’ written in pencil on the title page, and the year she’d bought it, if she’d bought it when she was a student, which seemed likely. Walsingham was her maiden name; she sometimes claimed to be descended from Sir Francis Walsingham himself, mostly when she was drunk. She sometimes said it was the only reason they’d let her in the Faculty at all, although nobody believed her. But it might say ‘Mary Exley’, if she’d bought it after we were married, when we were both already working there and she’d felt the need to remind herself she was an intellectual at heart, a scholar, which happened from time to time. I opened it instead at one of the pages where the corner had been folded down, and read aloud a sentence that had been underlined: Nobody is surprised when a fig tree brings forth figs.

Stephen was studying Philosophy – something else they hadn’t taught at my school – along with Greek (ditto) and English Literature. I’d done sciences, and read Biology at university. There was little chance that we would understand each other.

I said, “What does that mean, then?”

He shrugged.

“To you, I mean. You underlined it.”

Or it might have been Mary.

After a while he shrugged again. “What it says.”

I stood up and gave him back the book. He stood up, too, and took it with him up to his bedroom. I wished him good night.

The news was followed by a crime drama. It was a series and I hadn’t seen the earlier episodes, but I guessed I’d pick it up without much trouble. From upstairs I could hear the muffled peck – stuttering at first, but gradually growing more fluent, more rhythmic – of Stephen’s typewriter.

384081074098

38408107409817041974971947914719049174919479109480174182204108409171908401794700914909798180947982698287562094787236785620947871487289749834972984682984681409804370910461093487104697154671573265975027487629871237132719857019857097578517558357109

4714761947759125923

4579347523479234757194758234579283475234065184370561894517345783745708347572348957348081957981345961347592364501239561583478568903475897263945783465897345038957826304957187345038974571983485798345713457819034578964059179865074856823458762349572836453784628

93401523061982765102346120513254612312351059812674612651201589723198263571275681624571823571098425609182750816274590128705816274058761238956012850182650861285608712645908162086510982659812735086209861085670126506

A crock of shit

In the morning,Stephen usually got up before me and would be in the bathroom, doing whatever a seventeen year-old boy can do for so long in a bathroom –not shaving, obviously, or not often anyway – while I went down to the kitchen and prepared breakfast. I made porridge for Stephen, something else I’d never understand. I’d given up offering him eggs. Mary ate avocados when she could get them, bananas when she couldn’t, sprinkled with cayenne – and cigarette ash, if she wasn’t careful. I made toast, and tea.

I left for work before Stephen left for school, sometimes before he came downstairs, and the porridge would be cooling in the pan; he’d get back in the afternoon long before I did.

It was December, so in the train we all crushed up against each other in our overcoats, each of us leaking sweat and mucus, exchanging body fluids and avoiding eye contact. The train was on time and took no longer than usual, but that was bad enough. Dante, Mary used to say, might have run out of circles if he’d lived long enough to experience our suburban railway network. As we left the station a blind, merciless wind like a surgeon’s scalpel whipped off the river, sliced through our clothes and flesh, condensed the air in our lungs and cracked apart our bones to freeze the very marrow deep within. All, in my case, in the three minutes it took to cut between the buses that coughed and shuddered like old men at their stands, to cross the roads around the silent Butcher’s Arms and finally reach the blank, unlabelled airlock entrance of Faculty HQ.

On the third floor, Simmons was already at her desk. She was generally the first to arrive. Leach was just as often late because, to be honest, he was a lazy bastard; Butler was the most recent recruit to our team and didn’t seem to have that much to do. Maybe Gibbon had been breaking her in gently before he disappeared. She was twenty-seven, twenty-eight, I guessed, with a wide diaspora mouth and something of an overbite, which made her catch her bottom lip between her teeth and seem younger and more gullible than she was. She never came to the pub with us after work. She said she couldn’t drink, or watch other people drink. She rode a bicycle, a fold-up contraption she brought into the office, and wore short, stretchy skirts over sixty denier tights. She also had a thing for Leach – Simmons said, and I hadn’t really agreed or disagreed – which she had never declared, presumably because she never came to the pub and therefore never reached the condition you’d have to be in to admit to such a thing. That was Simmons’ theory, anyway. Perhaps I just wasn’t tuned in to the signals. It had been a long time since I’d taken interest in anything like that.

I hung my coat on the stand, but before I could sit down Simmons called me over to her desk. She asked if I would help her out with a case. I asked why she thought her case might be more important to me than any of my own, of which I had no shortage, and she said she didn’t. There wasn’t any reason. It was just that she was drowning, there was no way she could cope with her in-tray, that now we never saw Gibbon he seemed to be sending the stuff through faster and faster. I asked if she’d asked Leach. She gestured to his empty desk.

“But, if he were here?”

We both knew that she wouldn’t. She wouldn’t have contemplated it for more than a second, if that, because he wouldn’t have agreed. And even if he had, she probably wouldn’t have wanted him to.

I said, “All right.”

When you got down to it, one case was much the same as another.

She gave me the file, which was thick and had the name Volorik hand-written on a white label on the buff folder, the label stuck over three or four other labels as the folder itself had been used and re-used. Inside, there was enough paperwork to keep me reading till lunchtime, but none of it told me all that much, or not much that made sense. When I asked Simmons if she were coming to lunch she said no, she was too busy. Leach said he’d come if I were buying, and Butler, who never came to the pub, but sometimes came for lunch because it didn’t involve alcohol (except on the very worst days), said she’d come, too. I shrugged, to indicate that more would be merrier – not a sentiment I’d generally endorse, but if I had to have lunch with Leach, it would leaven the load for Butler to be there too. I asked Simmons if she were sure, but she said she was.

In the café Leach asked what Simmons’ case was about, the case I’d taken on for her. The place was crowded, the windows and even the tiled walls fogged with condensation, and we’d had no choice but to share a table. Butler signalled to Leach, gesturing at our neighbours – builders, by the look of their tool belts, boots and the yellow hard hats they’d moved off the seats when we sat down – as if Leach might not have noticed them. He sighed with exaggerated weariness and said, “Pas devant les civils?”

Butler gave me a complicit look I took to mean: what are we going to do with him? She said, “You think terrorists don’t speak French?”

Leach blew froth across the top of his coffee, the coffee I’d paid for, and said: “Nobody speaks French.”

“Apart from the French?”

“Apart from the French.”

“And the Senegalese,” she said. “The Algerians. The Cameroonians, the Haitians.” She paused for a moment. “The Canadians.”

Leach said, “Like I said.”

“Belgians,” I said. “Half of them.”

“Mauritians,” said one of the builders. “I am from Mauritius.”

“Guineans.”

Leach said, “Is that a word?”

I said, “Tunisians?”

“The Swiss,” said a second builder, who probably wasn’t Swiss. “Some of them.”

“Yeah,” I said. “But apart from them?”

“Nobody actually speaks French,” said Butler.

“Ha bloody ha,” said Leach. “Now we’ve established that, Exley, what’s the case about?”

I sighed. I looked at Butler. I tapped the side of my nose and said, “Fantastic.”

“What?”

“Spastic.”

Leach said, “I don’t think you’re supposed to say that anymore.”

“It’s rhyming slang.”

“Rhyming slang? Fuck off.”

Butler was gesturing to him to keep his voice down, but the builders were already joining in. “Mastic,” one said, in what might have been an eastern European accent.

“Drastic?”

“Elastic?”

“Periphrastic?” That was Leach, who could surprise you sometimes.

“Plastic,” said the builder from Mauritius.

“Ah,” said Leach.

“Indeed,” I said.

“Boom,” said Leach.

I nodded. “Boom boom.”

“That doesn’t work,” said one of the builders.

“Yes,” said Leach, “it does.”

“How?”

“If we told you that,” Leach said, “we’d have to kill you.”

Butler stood up, “Don’t worry about us,” she said. “We’ve got to go.”

Outside it was just as cold as it had been on the way in, which is to say cold enough to make you see the point of vodka. Butler said we ought to know better. I couldn’t hear her very well through the long woollen scarf she’d wrapped at least three times around her face. Leach said, “You think the walls have ears?”

“People have ears, Leach.”

I said I wouldn’t worry. The truth of it was that Simmons’ case – which was now my case, except that it would still be her name on the report that went back up to Gibbon, unless it all went pear-shaped and she found a way to weasel out of it – didn’t seem to be about much at all. There was plenty of paperwork, but none of it made sense and, while I hadn’t been exactly lying about the explosives – they were all over the file – I wasn’t at all sure they actually existed or would be used, if they did exist, for the purpose alleged by the people involved, if they were involved. Which I didn’t believe.

On the face of it, then, a crock of shit.

Which might mean it was just that: a crock of shit.

I said, “Qu’est ce c’est uncivil, anyway?”

The Crypt

That afternoon Imade some excuse and took the lift down to the Crypt, which might have been a floor or two below ground level, but wasn’t actually dark or damp or spooky. Whichdidn’t mean there weren’t ghosts down there. Some of the rooms were dark, it’s true, but not the sort of dark you might find in a sewer or a bomb shelter when the candles gutter out and you’re left with nothing but fear and the smell of death. It was more the darkness of an airline cockpit, punctuated with countless blinking LEDs and the electric hum of a thousand servers. Other rooms were lit like the inside of an abattoir. Calling the basement where the code breakers worked the Crypt had been somebody’s idea of a joke, a pun; unusually, it had stuck, perhaps because calling it the Basement wouldn’t work in a building where we all suspected there were other floors below it, though none of us knew how many or how to access all of them. There were doors where by rights there wasn’t any call for doors.

That afternoon, the Crypt’s famously brutal air conditioning didn’t feel much colder than the street outside. Warren was wearing a sick-green fleece under his white lab coat, which he generally did, although sometimes in summer it was a grey V-neck pullover with a purple trim in the neck that looked like it might once have been school uniform. Warren was a small man. Not just short – although he was; I’m not especially tall but I could comfortably have rested my chin on his head, had the occasion ever arisen – but also small-boned, like a garden bird, his sloping shoulders no wider than any of the countless buff folders on his desk. Only his head was adult-sized, the forehead higher and balder than most, the chin small and pointed, giving him the appearance of a cartoon megalomaniac’s captive mad scientist, or a miniature Roswell alien. He had been working at the Faculty longer than I had, longer than anybody could remember. The thick rubber soles of his shoes squeaked as he walked across the tiled floor to collect a single sheet from a printer, squeaked again as he returned to hand it to me.

Sdhl asodi id asdschop wiojdslkjhdf sdoifj oifj sdfjo oisd oisdif iojsd f s dfs dfs d f sdfjs df sodjf o cvoljsdfmnouz chi cvoiew apoi.

There was plenty more like that, but I didn’t bother reading it.

I said, “I preferred his early work.”

“He must have changed the book.”