Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Salt

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

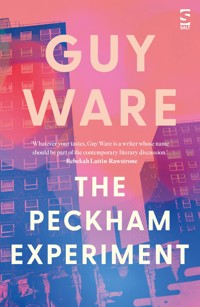

Guy Ware's new novel charts a course from the 1930s onwards through the fragmentary memories of the 85 year-old Charlie, whose identical twin brother JJ has recently died. Sons of a working-class Communist family, growing up in the radical Peckham Experiment and orphaned by the Blitz, the twins emerge from the war keen to build the New Jerusalem. In 1968, JJ's ideals are rocked by the fatal collapse of a tower block his council and Charlie's development company have built. When the entire estate is demolished in 1986 JJ retires, apparently defeated. Now he is dead and Charlie, preparing for the funeral, relives their history, their family and their politics. It's a story of how we got to where we are today told in a voice – opinionated, witty, garrulous, indignant, guilty, deluded and, as the night wears on, increasingly drunken – that sucks us in to both the idealism and the corruption it depicts, leaving us wondering just where we stand.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 328

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

i

PRAISE FOR THE FAT OF FED BEASTS

‘Fleshing out the shadowy metaphysical hints of Beckett’s novels, this intellectual romp is the best debut I have read in years.’

Nicholas Lezard, The Guardian

‘The staff of the office are revealed as gatekeepers to the afterlife, setting up a neat reversal in which determining the resting place of recently departed souls is treated like any normal job – employees rock up late and use work computers for their own projects – while mundane tasks, such as making couscous salad, are addressed with scholastic intensity.’

Sam Kitchener, The Literary Review

PRAISE FOR RECONCILIATION

‘Absent, slippery or suspect ‘facts’ are central to this unapologetically knotty novel.’

Stephanie Cross, Daily Mail

‘This ingenious novel succeeds in being both a highly readable story of second world war derring-do and its aftermath and a clever Celtic knot of a puzzle about writing itself.’

Jane Housham, The Guardian

‘Moving between various real-life events, each laced with errors and lies, Ware demonstrates to the reader how easily we can be misled as he explores the ethics of storytelling in this wartime thriller.’

Antonia Charlesworth, Big Issue Northii

PRAISE FOR THE FACULTY OF INDIFFERENCE

‘The Faculty of Indifference is both funny, diverting, exhausting and baffling all at once. Whatever your tastes, Guy Ware is a writer whose name should be part of the contemporary literary discussion. His is a post-modernism that pushes the past into our increasingly confusing world.’

Rebekah Lattin-Rawstrone, Byte the Book

‘Ordinary life is a terrifying prospect in this existential satire about a London spook … The Faculty of Indifference is a book of dark shadows and dry humour. It’s a comedy about torture, death and loneliness, and an existential drama about a world that swirls and twists and turns on us without provocation.’

James Smart, The Guardianiii

v

GUY WARE

THE PECKHAM EXPERIMENT

vii

For Sophy

And for my former colleagues inside the Castle

viii

ix

“If a man’s character is to be abused, say what you will, there’s nobody like a relative to do the business.”

Thackeray, Vanity Fairx

Contents

7th–8th of June, 2017

Diana fusses around behind me, plumping cushions on the sofa for no good reason, because these days I don’t make too much of a dent. She’s come to talk me out of it, I know she has, but I’m playing dumb. I don’t want her thinking I’ve any fewer marbles than I have, so I said earlier, when she arrived, Diana, darling, I said, when she let herself into the flat with the key she’s insisted I give her, just in case – she doesn’t say in case of what, but we both know – It’s always a pleasure, I said – lied – and she said: For me, too, Uncle Charlie, look, I’ve brought you some kitchen roll, and I thought: kitchen roll? What was the woman up to? But: Truly, I said, perhaps a little too quietly for her to hear, the wonders of the Orient, I said. Which was from a nativity we did here, at the Pioneer Centre, the old Peckham Experiment, when we were kids and you were Joseph – Joseph, for Christ’s sake – and it stuck in the family, the way things do, and

~KIT - CHEN - ROLL!

Diana shouts because she likes to pretend I’m deaf, or hard of hearing, she says. But: I’m not deaf, I say, just a little … overwhelmed, by your generosity. She says: You didn’t have any last time, remember? When you spilled your tea? We both know it was gin, not tea: can she not bring herself to say the word? – Unless it was brandy? Not gin? – It was not tea, anyway, although it was possible I had it in a teacup, I do that sometimes, so as not to offend her sensibilities. I say: Do you 2know what projection means? And she says, Speaking clearly? EEE-NUN-SEE-A-SHUN? Like the actors do? ~Very funny, I say. It means seeing your own subconscious fears and failings in another person, specifically, your analyst. And she says: Well, you’d know all about that, wouldn’t you? And really, what is she? Eight? – don’t say really – she doesn’t mean it, she knows I’ve never been in analysis, it’s not something the working classes do, or wasn’t, anyway, so what she means is: I’ve read books, I know big words. She means I always was a bit above myself, which can’t be a good thing, can it? So I say, You brought me kitchen roll, in case I spill my gin again and haven’t been shopping? What she’s trying to forget is that I’ve got my own slippers, my own teeth and – best of all – my own front door, even if she has a key as well, and okay, I have my own mobility scooter, too, but you can’t have everything, and I get around –

you do

– I do, which is the Beach Boys, like you didn’t know, 1964, all summer long, and so what if you were already too old for pop? Or what we called old, then, what we called pop, then, when we had no idea. So what if you were in your 30s? Because I was, too remember? ‘I Get Around’?

you always did

that’s right, I always did

All Summer Long was the LP

like you didn’t know.

I turn away from the table I use as a desk and wave the page at Diana. It’s all I’ve written up so far. She asks me what it is and I say: My script. For tomorrow. She says, It’s not a play. I say: Would you rather I … what’s the word? And anyway it is a play: I’m acting, I know exactly what the word is. I’m 3old, not gaga. ~What word, Uncle Charlie? ~The word I want. Would you rather I … ~Prayed? ~Good God, no. Don’t be stupid. Would you rather I … extemporized? Her face is pleasingly blank, and I’m pretty sure it’s horror, not incomprehension, which is what I’m after. She is picturing it. The risk. Given the choice, she’d rather I said nothing at all. She’s made that clear, but that’s not a choice she’s getting. I am his brother, as well as her uncle, and in this, I outrank her. If her mother – our sister, JJ’s and mine, our big sister: Angela, for fuck’s sake – if Angela were still alive, she’d outrank us all, and the entire funeral would be in her hands, which is a prospect I don’t imagine Diana would find any more comforting. If Angela were alive, she’d be, she’d be ninety-six, but more to the point, if Angela were alive the chances of her being sober would be slimmer than a flamingo’s shin. Which I suppose is why she’s not alive in any case.

Diana snatches the paper from my hand, scans it quickly and hands it back. I can’t read that, she says. There’s nothing wrong with my handwriting, not now. It didn’t help that you stole my pen, though, did it, JJ? Still, that Welsh night school bastard tortured it out of me. You might have A-levels, Charlie Jellicoe, though God knows how, maybe you bribed the examiners? No? You wouldn’t have had the money, would you? You may have A-levels, but you can’t be a QS if no one can read your numbers, now can you, Charlie Jellicoe? So my numbers are perfect, and the letters, the words, got dragged along behind, and still Diana says she can’t read what I have written – so I read it myself, aloud, editing as I go: The day my brother retired he killed a woman, not for the first time, I don’t mean a woman – well, okay, yes: a woman

she was a woman

And Diana says: You can’t say that. ~I know, I say, these 4days, it creates a certain … what’s the word? … a certain frisson. She’s looking blank. Come on, it’s not that hard. ~Not frisson, I say, expectation, prejudice. It makes him sound like a monster. Diana slaps at the sheet of paper in my hand and the sound is surprisingly loud. ~It’s a funeral, she says. You can’t say he killed anyone.

He did, though. And – to be honest – it wasn’t just a woman, was it? Not just any woman. Even if that really wasn’t the point. Not the second time, anyway. That’s what I was trying to get at – it’s that he never did anything else. Which isn’t right, either. I don’t mean he only ever killed people. That would be stupid, nobody ever only kills people, do they, however bad or mad they are? We all have a hinterland. Even Hitler liked to paint, Uncle Joe wrote poetry and loved his mother. Truly. Pol Pot? I don’t know. I can’t be expected to keep tabs on every homicidal dictator, now can I? Not these days – 100 minus seven equals 93, minus seven equals 86 – no, what I mean is that, afterwards, after the second time, he never did anything again, and yes, I know, he did some things, he ate and slept and no doubt wiped his arse, or had it wiped for him, towards the end. He’d meet me sometimes, for a drink: not here, in town – when he could fit it in between that charity stuff he did, towards the end, the food banks, and the woman he met there – when we both still went up to town to drink instead of doing it all at home, in bed, from teacups. But that’s not anything, really, is it? In thirty years? That’s not a life.

If the first time was tragedy, the second was surely farce? And after that, after ’86, he withdrew. For decades. W hat’s charity, after all? The last refuge of the scoundrel. Ask Profumo.

So what am I supposed to say? Tomorrow. What am I supposed to say tomorrow? At Honor Oak crematorium. That’s 5what you wanted, wasn’t it? The fire. I don’t get it myself. Maybe because there’ll be enough of that where I’m heading, if you believe. I don’t believe, of course I don’t believe. What do you take me for, Diana? All the same. What I want, when it’s my time – it is my time – I want a modest headstone – no, bugger that, an immodest headstone – in the corner of some ancient graveyard that Diana and the rest of them can feel guilty about neglecting for a year or two. Where little Dougie – Frances’ Douglas, that is, a boy after my own heart – can take his own sprogs and say: that’s your great uncle there – great-great uncle? – next to the grave of William Blake, or some such éminence grise. One of the more prominent Jellicoes, perhaps. A descendant of the first Earl Jellicoe himself. There’s enough of the buggers around, and not one of them related to us, as far as we can tell. And little Dougie’s offspring can look up at their father, tears in the corners of their bright blue eyes – eyes framed by perfect blond ringlets, I dare say – and lisp: What was great about him, Daddy? – It’s a great life if you don’t weaken – Does Dougie have children already? Does he? I think he might. I say already. He must be – what? – forty by now? Forty. Where are we? 2017 – so forty would make it 1977. That’s about right. Sunny Jim Callaghan, Provo bombs in West End pubs; battering the NF in Lewisham and Brick Lane. See? There’s nothing wrong with my memory, whatever the doctors think. Nothing. Even so. Even if I were to die tomorrow – which I won’t, but even if I did – Dougie’s nippers might be too old – if Dougie himself’s already forty – too old for the charming vignette of Hallmark waifery I’ve just conjured out of nothing. They might be grunting teenagers who never hear a thing their father says because their ears are plugged straight into Cupertino, CA.

We’re none of us getting any younger.6

It’s better than the alternative, I suppose.

You’d think I’d know. About Dougie. He’s Frances’ boy. You would think I’d know.

I can’t die tomorrow, though can I, JJ? Because tomorrow’s a date. Tomorrow we’ve got to vote. No. I mean, yes: vote – but then we’ve got to incinerate your corpse and scatter the grit on Peckham Rye. You were quite specific, at the end. And I’ve got to say a few words, and probably read something. Which, if Diana has her way, would probably be that Auden bollocks, but it won’t. We’re not stopping any clocks. Where would that leave us? – It’s a great life – Dougie doesn’t have children, does he? I remember now. He’s queer as a nine bob note. Runs a club in Vauxhall. A boy after my own heart, or some such organ.

There’s always Rochester. For the poem, I mean. Rochester, second Earl of: Dead, we become the lumber of the world. I could quote that. The lumber of the world. It was Bee who first told me about Rochester. And if she were there? Tomorrow. What would she say? That the man we are cremating is not the man she married, perhaps. But then, he never was. And if she read a poem? It’d be someone none of us had ever heard of. Some bright new hope from the inner-city borders of poetry and performance, perhaps. Is there still hope in poetry? In Rochester?

So what am I thinking, then? Me. Charlie Jellicoe. Peckham born and bred, orphan son of a Communist printer, mourning my identical twin brother by quoting the second Earl of Rochester, purveyor of seventeenth-century aristo-smut? What made me this way? What? That’s another story, not JJ’s. Nothing makes us, nothing made me. If Bee were there, tomorrow, I’d greet her like I always did, a kiss upon each cheek, a hug if these old arms of mine are capable of such a 7thing. I’d have to put my stick down first. I liked Bee, even if her enthusiasm could be tiring – this old heart of mine – That’s what it was. Not arms. The Isley Brothers, if I’m not mistaken, which I’m not, but you wouldn’t think an old coffin-dodger like me would know this shit, would you? I do, though. I really do. A lifetime of Forces Favourites, Family Favourites, that never were my bloody favourites, but what did I care? Radio Caroline, Radio 1, Radio 2: once they invented transistors you never got much choice about what you heard on the building sites, all day. It just seeped in. And, for most people, just seeped out again, I guess. But me, I’ve somehow kept my finger, if not exactly on the pulse, then at least somewhere not too far from the rapidly-cooling corpse of popular culture. This old heart of mine. Weak? Broken?

Nah.

Diana says, That was thirty years ago. She means the last death. The last time JJ killed somebody. ~You’re hoping everyone’s forgotten? ~There’s no need to mention it. ~But what else is there? She does that thing she does, tucking her hair behind her ears with both hands, running them around her jaw. It was cute when she was seventeen. She’s been calling me Uncle Charlie for almost seventy years. Since I was seventeen myself, and more like a cousin, really, than an uncle – Sinatra. See? – It was a very good year … it bloody was, I tell you. Seventeen. It was 1948, the year the NHS was born, and all the rest of it. ~You’re his brother, Uncle Charlie. What am I supposed to say to that? ~You should tell some stories about growing up together. Say how committed he was to building decent houses for the poor. Say you loved him. That’s all anybody wants to hear. That’s what she says, and … I nod. It’s the longest speech I’ve heard her make in years. I give her 8the impression that I think she’s right, after all. That it really is that simple. I even say: You’re right. Though we don’t call ourselves the poor any more, do we? We don’t. I’m not poor, not any more. And neither were you. But that’s not what I mean. We talk about disadvantage and low-income families. At a pinch, we might just talk about poverty – as an abstract noun, like Beveridge’s giant evils Want and Squalor – and, God help us, about social mobility, as if it was all about a few smart kids getting richer – a few smart kids like us – but never, not ever, about people being poor. About poor people. It’s not polite. It’s demeaning. As if being hungry enough to feed your kids from a food bank and living six to a mould-covered room you might get kicked out of tomorrow weren’t demeaning enough, and – I don’t say any of this – Diana smiles and clicks her teeth, relieved. ~I’ll be here about ten to pick you up. I get around. I could get there on the Easy Rider. Not a bad way to turn up at a funeral. Pale horse, be damned. ~Don’t worry, I say. ~It’s no trouble, she says. Except it is, isn’t it? For her. Driving through the Rotherhithe Tunnel at rush hour. I can’t think what possessed her to move to Mile End. A man? A job? ~I’m going to vote first, I say. You should, too. I don’t say It’s what he would have wanted – which would be laying it on too thick, even for Diana. She says she supposes so, though it won’t make much difference where she lives. It won’t make much difference here, either. Harriet-bloody-Harman isn’t going to lose a twenty-five thousand-vote majority. ~That’s not the point, I say, piously. We vote: it’s what we do. There’s nothing she can say to that. She offers me tea; I decline. And so she leaves, at last. But on her way downstairs, she says: I’ll see you at ten. And shuts the door behind her.

It’s 4.15pm. I have eighteen hours. Surely that’s enough?

What about a drink, to lubricate the gears? Not yet. It’s 9only teatime. Not that I’ve ever been one for all that sun below the yardarm bollocks. A drink’s a drink, whether it’s ten in the morning or ten at night. How long is it we’ve had all-day opening? Years. Decades? Possibly. Wasn’t it Blair? Opening hours never meant that much to me. Don’t get me wrong, I loved pubs. Still do. I love the noise on a Friday night, and the quiet on a Tuesday afternoon. I love the bevelled glass and the polished wood, the peanuts and crisps and the barmaids you can flirt with and the young men at the bar who don’t flirt, at least not with barmaids, and the landlord banging the bell and telling us all to bugger off, and, yes, he does mean bugger. I love the beer and whisky, the brandy and the gin. It’s just, for me, pubs have never been the only – or even the best – place to drink, and – I’ll tell you what else happened in 1948. Larry Olivier made Hamlet. This I know I know because Angela dragged us to the Tower on Rye Lane to see it twice because, she said, it might help us with our exams, and after that she always thought she was quoting the Prince of Denmark on a Saturday night when she said: There’s nothing either good or bad, but drinking makes it so. She was wrong, of course. She had what Diana might call a problem with alcohol, if Diana could ever bring herself to talk about her mother. (The problem being, naturally, that she couldn’t get enough. Ba-bum-tish.) Then JJ and I grew up, and her kids grew up and she discovered that booze was more important than paying the bills, and it wasn’t a problem for a while. For most of the 60s she was fun to be with, as long as you got to her early in the day. Which was fine by me. I had other things to do at night. Then the bank tried to repossess Tony’s Hillman Hunter, and all of a sudden it was a problem. You tried to stop me seeing your mother, then, didn’t you, Diana? You said I was an enabler. Even Frances told me I had to stop 10bringing sherry, and – I listened then, because it was Frances, Angela and Tony’s second, more lovable daughter, but – you were never the problem, were you JJ? Never an enabler? – I place both hands on the head of my stick and lever myself out of my chair. It’s a knobkerrie. The stick. A beautiful word – a beautiful thing. Ash, or birch, or some such. I’m not really one for trees. It’s none too practical for hands as palsied and cramped as mine, but beautiful all the same. I tell Diana I keep it because, if push came to shove, and shove to assault, I could still crack a man’s skull with its heavy, polished knob. She doesn’t believe me. These days I mostly use it round the flat. I keep the Rollator by the door. A walking frame with wheels and a nifty fold-down canvas seat for when the walking gets too much. I try not to use the scooter unless I have to, even though it’s an Easy Rider and cool as fuck, as I believe the saying is. Or was. I get around. I keep the stick because, beneath it all, I am a sentimental fool. I hobble to the kitchen, fill the kettle at the adapted tap and make the tea I refused from Diana.

Back at the table, I place the hot mug carefully on an almost antique coaster with the word PRIDE in fake old-timey print capitals like the lettering on a wanted poster. Except rainbow-coloured. What would Mum have thought of that?

She’d probably have been made up to see you use a coaster.

I look again at the page I’ve written. I squint. Perhaps Diana has a point. Am I going to be able to read this tomorrow? In my experience the lighting in crematoria is not too bright. Perhaps I should type? I have a laptop Dougie bought me. I can print things in huge fonts, thirty-six, forty-eight-point type, so that’s what I will do. I take the computer out of its case and boot it up, and while it’s doing whatever it is 11they do that takes so long, I fold the handwritten sheet I’d shown Diana and tear it in half, but carefully, carefully. I can always type it out again.

The trouble is, there was nothing else. Nothing after. But what about before? Is Diana right? Or maybe not just boyhood stuff, but all the way back. Ab ovo, a teacher who couldn’t tell JJ and me apart, once told us. He wasn’t alone. Tony couldn’t, either. I’m not sure Angela was always sure, but – anyway – the teacher got sidetracked onto twins in history. He told the class about Leda and the Swan, and the eggs; about the twins Castor and Pollux and about Helen without whom, he said, stressing the ‘m’, sphinctering his lips as if kissing an aunt, without whom, no abduction, no Trojan War. Hence the phrase, he said. ~What phrase? we said. ~Ab ovo. Meaning? ~From the egg, sir. ~Good. From the egg, yes. But, figuratively, from the beginning. The origin. The cause. I could start again from the moment, perhaps, the twin moments, I should say, of our births. Me, the eldest; he, Jolyon, decidedly not clutching at my heel, a reluctant Jacob to my Esau: my brother is an hairy man, or was: I am the smooth one. Or so it is alleged. Whose birthright was whose? I am older. This should not be happening. Ten minutes I had her to myself, before you came along. Except I didn’t really, did I? She was up to her eyes in you, flat on her back on the kitchen table – she wasn’t going to ruin the bloody mattress, was she? – ten minutes pushing and screaming like a banshee, the midwife looking to me, tying off the cord and calling to her: Push! You’re nearly there, you’re nearly there, push! Push! And Mother screaming back blue murder: fuck, fuck, I’m pushing! Fuck fuck fuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuccccckkkkk! Is that any way to meet your mother? To be introduced? And what was it all 12for? All that fuss? Because, let’s face it, JJ, you were the easy one, the one who slipped into the world, and slipped through life. I was the one causing all the pain.

And where might Dad have been, while all this was going on? Well, it was late at night her labour started, and about four in the afternoon before the whole grisly business was done. Time for tea and cake, though there wasn’t often cake. Four on a sweltering afternoon in the high summer of 1931, it was, so I imagine he wouldn’t be home for another couple of hours, at least, if it was a weekday. I don’t know. Do you? I only know the time because Mum told us, whenever she wanted to rub it in. So he’d have been home about six, or much later if there was a branch meeting that night, or a committee for the defence of this or that, or red and black leaflets and posters to print, after hours, once Manny, the owner, Mr. Levinson that is, had left. He was Dad’s boss, but also his friend – which was ironic, really, Dad having a boss for a friend: but Manny, Mr. Levinson, was never what you’d call a capitalist – more of a kulak, perhaps – and once he went home he turned a blind eye and left Dad to it, the presses still running, the keys in a bunch hanging underneath the counter. In which case, it might have been hours, midnight, before Dad got home and found that, ten years after Angela, he’d finally become a dad again. Ten years.

So burying Angela made sense to me. She raised us; we’d bury her. The way it’s supposed to go. At least till Tony got up and read the kind of eulogy I’ll be buggered if I’ll read tomorrow. Lot of vapid nonsense. I don’t even know what he was doing there. She’d left him. So what, they never divorced? She’d left: at least, she hadn’t gone home. Not for the last couple of years. Pillar of the community, my arse. He might as well have been the vicar. We swore then, JJ and me, we swore 13we wouldn’t let that happen to us, to each other. We swore, like we were ten years old again, newly orphaned, cutting our palms and mingling our blood, but – I never believed I’d bury him. I’m older. Surely it should fall to you to bury me, JJ? Perhaps you thought the same. No one wants to be last, and, really, there’s nothing to choose between us, actuarially speaking. It could have been me. I could have been you. Tell me you know what I mean? I drank more, but gave up smoking earlier. These things surely cancel each other out? We should have gone together. That would have been better. A plane crash, maybe, though it’s been years since anyone would let either of us on a plane. A freak meteor strike at a family picnic? I’m not sure which is less likely, the meteor or the picnic.

When Tony finished, we read poems we’d brushed up for the occasion. Me: Herbert. You: Larkin. Which was sly of you, I thought. Of course, you had no more children than me, or the librarian of Hull. Angela had two: Diana and Frances. Our mother, three: Angela, when she was young; and then, when she really wasn’t, you and me together, and neither of us tiny. We must have nearly been the death of her.

So she said, often enough.

But surely never meant.

It was cheese, in the end, that was the death of her, and of our father, not us. Or stout. Or something that roiled her dyspepsia and brought her bolt upright at four am – something else she left me – when she’d only gone to bed at half past two. It kept her awake until she thought she might as well get up and make a cup of tea, or Horlicks, or whatever it was that made her light the gas at a quarter to five, or thereabouts, and – wasn’t that Ronan Point? – the all-clear had sounded just before two: they’d survived, again. She wasn’t to know a direct hit a couple of houses up the road had left a bomb that 14wouldn’t explode until it was found and carted away years later, but which had nonetheless ruptured a pipe and filled her kitchen with gas – 1968? Some other mother? – I forget. Let’s nudge the Heinkel’s bombsight up a fraction of a degree and – there we go: our house obliterated with appropriate dignity.

JJ sighed, the last time we discussed this, our funerals. Who’d go first. For some people, I remember saying, the world is made afresh each morning. ~Isn’t it, you said. ~Maybe, but it bores us to tears all the same.

The last time? I don’t forget. The doctors’ questions are always the same. ~Can you tell me who the Prime Minister is, Mr. Jellicoe? ~May, Cameron, Brown, Blair. ~Excellent. Now can you count down from a hundred in sevens? ~Of course I can. There’s nothing wrong with me. More’s the pity.

It was – what? Ten years ago? Less. You’d started in at the food bank by then, dishing out Pot Noodles to victims of Universal Credit. You talked about Momentum. Momentum, for Christ’s sake! It was like your second childhood. We met in a pub on Old Compton Street that had been blown apart a decade earlier – I’ll get back to that – in the late afternoon, the light outside already more neon than sunshine. Four men, all middle-aged – younger than us, at any rate – sat at two separate tables, each of them scrolling wordlessly through mobile phones. ~For Christ’s sake, people! I said, too loudly. Drink. Eat! Laugh! They ignored me, in that careful way we all ignore people – even harmless old men like me – who shout in pubs in the afternoon. JJ, too. JJ sipped his whisky and ignored me. ~You’re going to die. You know that, right? Of course they knew. ~You’re going to fucking die. Which didn’t mean they’d want to talk about it. ~Make the best of it, I said, 15defeated. You asked if I remembered you once asking me if I enjoyed life. ~Of course I remember, I said. Were we drunk? ~We’d had a drink, you said. Of course we had. It had been 1960-something. Even then we were too old for that sort of conversation. ~I remember, I said. You asked if I enjoyed my life. Not Life. No capital L. My life. And I said: Of course. What else was there? And you said: Purpose. Meaning. And I said –

~You said: Where’s the fun in that?

Now – by which I mean: then, on Old Compton Street, some years ago – it was 2012 or so and we, JJ and I, who’d never really believed we’d see the twenty-first century, and never really believed it when we did, we watched those four men put away their mobile phones and leave, two-by-two. And we kept watching, kept drinking our whisky, while six more men – younger, more attractive men – arrived. Such is life. What can you do? What can anybody do?

How much of this can I repeat tomorrow?

There’s love, of course. Purpose, meaning, he said, but never mentioned love, even though that was one thing he did have in his life, whatever happened later.

My tea is cold. It is five p.m. Time for P.M. May, Cameron, Brown. And after tomorrow? Corbyn? Fat chance. Improbable, to say the least. Eddie Mair can wait.

There’s love. And marriage. Of course. Putting the horse before the carriage. An autumn wedding, for reasons I can’t recall. Not everything’s still there. If my brother chose to get hitched in October, who am I to second-guess his motives? Or Bee’s? Or – more likely, now I think of it – Bee’s mother, “Lady” Antonia’s, motives. Shotguns were not involved, I know that much. Her family approved of JJ, in their own way. He 16was a working class boy – no longer a boy – but this was 1959, and there’d be room at the top for a grammar school lad with a degree, with National Service behind him and a bright, bright future ahead, rebuilding Britain. I dare say they’d have preferred a proper profession – an architect selling to the council, perhaps, rather than working for it. What exactly did a housing manager do? Was that a new thing? And wasn’t it a shame not to use his degree? To be a smooth, and not an hairy man. But even Tories loved slum clearance in 1959. And if JJ insisted on working in the inner city, they could put that, too, down to the spirit of the times. You were amiable enough, then, weren’t you? Idealistic, yes, but you were young, “Lady” Antonia said, and you never shoved it down their throats. Meaning: not like your brother, not even like their daughter. You’d be a steadying influence on Beatrice. Total bollocks, but she wished it so.

And what of me, then? I’d have been cool, of course, in the oyster-grey Continental-cut single-breasted suit that Tomas-the-tailor had persuaded me into, with its short jacket and lapels so narrow and so sharp I could slice my fingers open just fastening the mother-of-pearl clip on my green silk tie. The hat? No hat. This was 1959. The year of the M1 and Ronnie Scott’s. We were the future. My collection of homburgs, trilbies and fedoras – lovingly gathered and preserved since I’d left the RAF and begun buying my own clothes (or having them bought by grateful friends) – had been temporarily demoted to the back of the wardrobe, along with the box-back double-breasted suits with shoulder pads like rocket fins and chalk stripes like aircraft landing strips. Fashion is fickle, I knew: their time would come again. But I wouldn’t have been in one of my suits, would I? Because it was your wedding, yours and Bee’s, and for all you thought yourself 17the future, the modern man, you’d decided, or agreed with Bee’s mother – against Bee’s better judgment, I would guess; which says a lot, in retrospect. Her parents were paying for everything, after all, everything except the ring, which had been our mother’s – no it hadn’t: Mum had been blown to smithereens and we weren’t around to sift the remains for usable accessories – and you’d agreed, decided, agreed to go for morning dress from Moss Bros. Now, it wouldn’t be the first time I’d worn a suit that had been worn before by another man, but it was the first time I hadn’t met the man in question first, hadn’t stood at his wardrobe, flicking idly through the hangers waiting for him to say: the blue, I think, on you, or perhaps the – no, not that one, darling, it was a present. Or hadn’t rifled brazenly through another’s collection while he, no doubt thinking our relationship more than it was, foolishly left me alone in his flat while he took care of business somewhere in the City, or Whitehall, or wherever. My point being that I was not wholly agin the whiff of another man. I liked the faint odour of alien bodily fluids that could be released when least expected, when the fabric was brushed or creased by sudden movement. It could be romantic. There I’d be, stuck in some municipal office with a huddle of recalcitrant town planners, transported with a Proustian rush to a different world of illicit pleasure. But I’m getting ahead of myself. The point being that, no, I wasn’t bothered about going to my brother’s wedding in a suit that wasn’t mine, but there was a world of difference between appropriating another man’s tailoring – from each according to his ability; to each according to his needs, after all – and the cab-rank, pseudo-democracy of wearing clothes that have been worn by any old body with sufficient dosh to hire them. It’s the difference between a Soho members’ club and a Gents toilet. I’ve never been a 18snob, but I’ve always picked and chosen, and I’ve never been a whore.

I told JJ and Beatrice I was not happy. Bee said, Moss Bros was good enough for the Coronation. ~Good enough for Ramsay Macdonald, too, said JJ. They kitted him up for visits to the Palace. ~I bet they didn’t stuff him in trousers steeped in the sweat of a dozen commercial reps, though, did they? ~They do clean them, Charlie. Which wasn’t much better. Well, it was, I suppose, but still. I said: They’ll dry clean them. ~Exactly, JJ said. ~So they’ll stink like ICI and be brittle to the touch. When I was introduced to Tomas – the best gift anyone ever gave me, by the way, from a man I can’t remember anything else about – and Tomas made the first suit ever made especially for me, he insisted dry cleaning was an abomination. Nothing would ruin the wool or the hang of well-made clothes more effectively than the solvents and steam presses those charlatans employ. Tetrachloroethylene was not his idea of style, and consequently not mine, either. In all but the most extreme cases, he declared – the spillage by a tipsy waiter of a whole tureen of borscht into one’s lap, for instance – it is better to sponge clean with a damp cloth and hand press with a domestic iron. Better still, naturally, to have one’s valet do it, but I was never in that class, and never wanted to be. Tomas knew that. He was only teasing. He was Hungarian and one of the few straight tailors I’ve ever met with any real claim to flair. His shop was in Bermondsey. Not because he couldn’t have been in Savile Row, but because that’s where he chose to be, and considered he had chosen well. He felt no need to move. Come the wedding, JJ said: You could have yours made, if you can afford it: Bee’s dad isn’t going to pay for that. He knew I couldn’t afford it. It would be some years before I could settle Tomas’ bills myself. ~You’d have to make JJ’s too, 19Bee said. They have to match. ~Do they? Why? It had been a month or two of heavy outlay, what with the wedding present and the deposit on the double room in Bute Street. I wasn’t keen to spend money on a suit I’d never wear again. It wasn’t as if I’d be getting married myself. Still, I tried to imagine the look on Tomas’ face if I took him JJ’s rental and asked him to copy it for me. ~They just do, Bee said. The fitting’s next Thursday. ~I thought it was this week? JJ said. ~No, sweetheart. The eighth. Mum sent you the appointment card.

We were in JJ’s room at the time, the one in Deptford, before he moved – before the council knocked the whole street down. I was sitting on the bed because there were only two chairs. There were boxes stacked under the bed, under the sink, under the small table. One balanced precariously on top of the hot water geyser. Boxes of leaflets and posters straight from the printers.

~But that’s election day. ~I know. ~How could you? ~I didn’t. Mum did. ~Of course she did. She wouldn’t want us getting out the Labour vote, now, would she? ~You’re being silly, JJ. We knew you’d both be taking the day off anyway, and it won’t take long. We’re going over to Mum’s afterwards, so we could canvas there. It’ll do more good than here.