Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Allen & Unwin

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

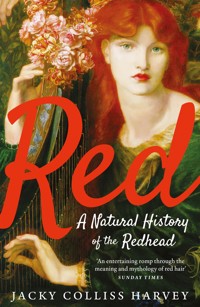

A New York Times bestseller Red is the first book to explore the history of red hair and red-headedness throughout the world. More than just a book for redheads, Red is a fascinating social and cultural celebration of a rich and mysterious genetic quirk. With an obsessive fascination that is as contagious as it is compelling: the book explories red hair in the ancient world, the prejudice manifested against redheads across medieval Europe, and red hair during the Renaissance as both an indicator of Jewishness and the height of fashion in Protestant England, thanks to Elizabeth I. It also examines depictions of red hair in art and literature, looks at modern medicine and the genetic decoding of redheads, and considers red hair in contemporary culture, from advertising to 'gingerism' and bullying.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 359

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

‘Fascinating’ Guardian

‘Jacky Colliss Harvey sets out to discover everything – what it takes to make a redhead, where in the world they come from and why they exist at all133… [Her] project is personal… Red is a memoir as well as a study.’ Spectator

‘She is as comfortable with the science as she is with cultural history… Colliss Harvey is especially informative on red hair in painting.’ Oldie

‘Harvey is eloquent on the cultural expectations that surround redheads’ TLS

‘Wide-ranging… hard to resist’ Country Life

‘A light touch and a lively style… intellectually wide-ranging and searching when it comes to issues of discrimination.’ Wall Street Journal

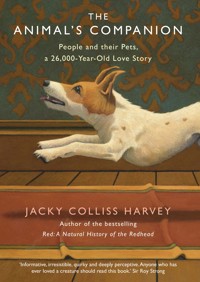

Also by Jacky Colliss Harvey

The Animal’s Companion: People and their Pets,a 26,000-Year Love Story

First published in hardback in Great Britain in 2015 by Allen & Unwin, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

This paperback edition first published in Great Britain in 2016 by Allen & Unwin, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Jacky Colliss Harvey, 2015

The moral right of Jacky Colliss Harvey to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

No part of this book may be used in any manner in the learning, training or development of generative artificial intelligence technologies (including but not limited to machine learning models and large language models (LLMs)), whether by data scraping, data mining or use in any way to create or form a part of data sets or in any other way.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Paperback ISBN: 978 1 80546 626 0

E-book ISBN: 978 1 92526 658 0

Interior design by Cindy Joy

Printed in Great Britain

Allen & Unwin

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

Product safety EU representative: Authorised Rep Compliance Ltd., Ground Floor,

71 Lower Baggot Street, Dublin, D02 P593, Ireland. www.arccompliance.com

This one is for Mark.

CONTENTS

Introduction

Chapter 1: Way, Way Back, Many Centuries Ago

Chapter 2: Black and White and Red All Over

Chapter 3: Different for Girls

Chapter 4: The Excrement of the Head

Chapter 5: Sinners and Stunners

Chapter 6: Rapunzel, Rapunzel

Chapter 7: Freaks of Fashion

Chapter 8: Redhead Days

Reading for Redheads

Acknowledgments

Art and Photography Credits

Index

The Redhead Map of Europe.There is a good deal of controversy over the accuracy of such maps, as there is indeed over so many issues associated with red hair, but what it shows very clearly is the hotspot in Russia of the Udmurt population on the River Volga and the increasing frequency of red hair the farther north and west you go, whether in Scandinavia, Iceland, the British Isles, or Ireland.

INTRODUCTION

The study of hair, I found out, does not take you tothe superficial edge of our society, the place whereeverything silly and insubstantial must dwell.It takes you, instead, to the centre of things.GRANT McCRACKEN, BIG HAIR, 1995

I am the only redhead in my family, a situation with which many a redhead will be familiar. My mother, now gray-haired, was blonde (was still a blonde, well into her seventies). My father’s hair was dark brown. My brother is also blond. My brother’s kids have hair that shades from brownish to blondish to positively Aryan. Yet mine is red. When I was little, it was the same orange color as the label on a bottle of Worcestershire sauce; with age it has toned down, to a proper copper. It is not carrots, nor ginger, nor the astonishing fuzz of paprika I remember on the head of a girl at school, a child with skin so white it was almost luminous. I’m not quite at that end of the spectrum, but I am red. It is, with me, as with many other redheads, the single most significant characteristic of my life. If that sounds a little extreme to you, well, you’re obviously not a redhead, are you?

Red hair is a recessive gene, and it’s rare. Worldwide, it occurs in only 2 percent of the population, although it is slightly more common (2 to 6 percent) in northern and western Europe, or in those with that ancestry (see the map on pages viii-ix).1 In the great genetic card game, the shuffling of the deck that has made us all, red hair is the two of clubs. It is trumped by every other card in the pack. Therefore, for a red-haired child to result, both parents have to carry the gene, which, blond- or brown-haired as they may very well be, they can be carrying completely unaware. So when a baby appears with that telltale tint to its peach fuzz, expect many jokes and much hilarity. For all my toddlerhood, my mother would blithely ascribe my red hair to either her craving for tomato juice during her pregnancy or to a mysterious redheaded milkman. My grandmother, meanwhile, was fond of quoting the wise old saying that “God gives a woman red hair for the same reason He gives a wasp stripes.” But then she was a native of Hampshire, a West Country girl, where redheads were once also known, charmingly, as Dane’s bastards, so really, that was letting me off lightly.

I was five before I realized there might be more to being a redhead than incomprehensible teasing by adults. My village school in Suffolk was terrorized by a kindergarten Caligula, a bully from day one, whom we’ll call Brian. The rest of us five-year-olds watched in disbelieving horror as Brian roamed about the playground, dispensing armlocks, yanking out hair by the roots, and knocking down birds’ nests and laughing as he stamped on the eggs, or fledglings, inside. His genius was to find the thing most precious to you and destroy it. One afternoon at the end of a school day he came up behind my friend Karen, who was sporting a new woolly hat of a pale and pretty blue with a large fluffy bobble on the top. Brian seized the hat from Karen’s head, ripped off the bobble, and threw it to the ground.

I can still summon up the extraordinary feeling of liberation as the red mists descended. I wound up my right arm like Popeye and punched Brian in the face.

It was a fantastic blow. Brian was knocked flat. As he made to get to his feet, his eye was already swelling shut. Most incredible of all, Brian was in tears. Only then did I realize that my David-and-Goliath moment had been witnessed by all the mothers arriving at the school gate to collect their children, my mother included.

One did not punch. I knew this from the number of times I’d been told off for fighting with my own younger brother. I imagined my punishment. I awaited my mum’s reaction, and the reactions of the other mothers at the gate. I was proudly unrepentant, but I knew I was also in any amount of trouble.

The punishment never came. Someone—one of the teachers, I think—picked Brian up and brushed him down. There was laughter. There was an air, astonishingly, of adult approval. My mum, who seemed embarrassed, took my hand and began to hustle me down the road. “Well, what did he expect?” one of her friends remarked, above my head. “She’s a redhead!”

She’s a redhead. I was five years old, and I had just learned two very important lessons. One, that the world has expectations of redheads, and two, that those expectations give you a license not granted to blondes or brunettes. I was expected to lose my temper. I dutifully produced appalling tantrums as a child. I was meant to be confident, assertive, and, if I wished, slightly kooky. I could be a screwball. I could be fiery. As I grew older, the list of things I was allowed to do, simply because of the color of my hair, increased. I was allowed to be impulsive. I was allowed to be hot-blooded and passionate (once I reached the age for boyfriends and relationships, it seemed I was almost required so to be). The assumptions and expectations the world made about me and my fellow redheads were endless. I must be Irish. Or Scottish. I must be artistic. I must be spiritual. Was I by any chance psychic? And I must be good in bed. There’s a point where all those “musts” start taking on the tone of a command. She’s a redhead. That was all the world need know, apparently, to know me.

I grew up, and the world got bigger, too. I taught English to a brother and sister from Sicily who were even redder haired and paler skinned and bluer eyed than I am. How did that happen? I traveled farther. I discovered new attitudes toward my red hair, not the same at all as those I had grown up with. Yet the common denominator in every reaction I experienced was this: redheads were viewed as being different. And there has, of course, to be a point when you start asking yourself why. Why these assumptions? What’s their basis? Do they even have one? Why do they differ from one country to another? Why have they changed, or why have they not, from one century to the next? Where do redheads come from, anyway?

The term “redde-headed” as a synonym for red hair can be tracked back at least to 1565, when it appears in Thomas Cooper’s Thesaurus Linguae Romanae et Britannicae, otherwise known as Cooper’s Dictionary.2 This mighty achievement, admired by no less a redhead than Elizabeth I, who made its author Dean of Christ Church Oxford as reward for his labors, is a building block of the English language and is believed to have been one of the most significant resources used by that great word-smelter William Shakespeare. But the specific chromosome responsible for red hair was only identified in 1995, by Professor Jonathan Rees of the Department of Dermatology at the University of Edinburgh.3 So for almost the entirety of its 50,000-year existence on this planet, red hair, across every society where it has appeared, has been wrestled with as an unaccountable mystery. In the search for an explanation for it, it has been hailed as a sign of divinity; damned as the awful consequence of breaking one of the oldest sexual taboos; ostracized and persecuted as a marker of religion or race; vilified or celebrated as an indicator of character; and proclaimed as a result of the influence of the stars. It is, unsurprisingly, none of these things, yet at the same time, society’s—any society’s—responses to red hair have become so inseparable from the thing itself that it has become all of them. And there is as much mistaken nonsense written about it now as there was a hundred, or two hundred, or, for that matter, five hundred years ago.

Let me illustrate what I mean here by way of a famous redheaded tale, which functions almost as a parable. In 1891 Sir Arthur Conan Doyle published the classic Sherlock Holmes short story “The Adventure of the Red-Headed League.” The redhead at the center of the tale is a pawnbroker, Jabez Wilson. Owing to the particular tint of his rare red hair, Jabez is selected by the mysterious League and lured from his pawnbroker’s shop to an empty office, where he is paid to spend his time pointlessly copying out chunks of text from the Encyclopedia Britannica—a task that, according to the League, he and only he, with his unique flame-red hair, is fit to do (you can see why this wouldn’t have worked as a ruse were he garden-variety blond- or dark-haired). Sherlock Holmes, of course, spots at once that the pawnbroker’s shop sits next to a bank and that the “work” offered to Wilson by the Red-Headed League is no more than a trick to get him out of the way. The League is simply the cover for a gang of robbers who plan to break into the bank through the pawnshop’s basement; and Jabez has been selected not because of his hair but because of the location of his shop. In other words, it is a story whose final explanation is completely different from the one you might expect. In exploring the history of red hair, such will very often prove to be the case.

We live in this extraordinary age in which a butterfly flapping its wings on one side of the planet truly can create a tornado on the other—but only if the butterfly then sets up a website. There is an entire alternate solar system of knowledge and its opposite circling around up there. This is often quite miraculously wonderful—I can fly across the wastes of the Taklamakan Desert in western China, ancient home of the mysterious blond and redheaded Tarim mummies, like Luke Skywalker in his landspeeder, then order up the definitive account of the mummies’ discovery by simply dipping my pinkie. What would once have been completely beyond human imagination is now as quotidian as a grocery list, and it seems we are all putting them together. In this universe of information and of unformation, some are born redheaded, some achieve it, and some poor souls simply have it thrust upon them. There are endless lists of supposed historical redheads out there, a tangle that links one site to another like binary mycelia; layers of space junk that typify redheads as impulsive, irrational, quick-tempered, passionate, and iconoclastic; great drifting rafts of internet factoids (currently the most notorious: the notion that redheads are facing extinction), with repetition alone creating a kind of false positive, a sort of virtual truth by citation. This, I discovered to my delight, is known as a “woozle,” after the mythical and perpetually multiplying beasts hunted in the Hundred Acre Wood by Winnie-the-Pooh and Piglet, way back in 1926. It takes Christopher Robin to point out that the pair are simply following their own ever-increasing footprints in a circle around a tree. This book will endeavor not to add to the population of woozles.

Red is a color that has exceptional resonance for our species. There’s an argument that it may have been the first color early primates learned to distinguish, in order to be able to select ripe fruits from unripe, and it still seems to speak to something primal in the human brain today: those suffering temporary color blindness as a result of brain damage are able to perceive red before any other color. And it is full of contradictions. It is the color of love, but also that of war; we see red when furiously angry, yet send our love a red, red rose; it is the color of blood, and can thus symbolize both life and death, and in the form of red ochre or other natural pigments scattered over the dead, it has played a part in the funerary rites of civilizations from the Minoans to the Mayans. Our worst sins are scarlet, according to the prophet Isaiah, and it is the color of Satan in much Western art, but it is the color of luck and prosperity in the East. It is universally recognized as the color of warning, in red for danger; it is the color of sex in red-light districts across the planet. The symbolism and associations of red hair embody all these opposites and more.

Red hair has always been seen as “other,” but fascinatingly and most unusually, it is a white-skinned other. In the aristocracy of skin, as the historian Noel Ignatiev has described it, and in the Western world of the twenty-first century, discrimination is rarely overtly practiced against those with white skin. Yet people still express biases against red hair in language and in attitudes of unthinking mistrust that they would no longer dream of espousing or of exposing if the subject were skin color, or religion, or sexual orientation. And these expressions of prejudice slip under the radar precisely because by and large there is almost no difference in appearance (aside from the hair) between those discriminating against it and those being discriminated against. It is as if in these circumstances, prejudice doesn’t count. Attitudes toward red hair are also extraordinarily gendered, something we’ll encounter very frequently in the following pages. In brief, red hair in men equals bad, in women equals good, or at least sexually interesting. But even within this simplistic categorization there is a glaring contradiction, since culturally it seems we can get our heads around red-haired men as both psychopathically violent (Viking berserkers; or in the UK, the drunk swaying down the street with a can of super-strength lager in one fist and on his head a comically oversize tartan beret, complete with fuzz of fake ginger hair; or even Animal from The Muppets), and as denatured, unmasculine, and wimpish (Napoleon Dynamite, for example, or Rod and Todd Flanders from The Simpsons). Stereotypes of redheaded children reflect these opposites, with red hair being used to characterize both the bullied and the bully—Scut Farkus in the movie A Christmas Story being a memorable example of the latter—unless the children in question are girls, in which case they are generally perky (Anne Shirley in Anne of Green Gables) and plucky (Princess Merida in Disney’s Brave) and winningly cute (Little Orphan Annie). Redheaded women are supposedly the least desired by their peers of the opposite sex among American college students; yet (and I have to say, this has been my own experience) the popular construct of the female redhead is often profoundly eroticized and escapes the rules and morality applied to the rest of female society.4 For this far from godly point of view, we have in large part to thank the medieval church.

This happens with red hair, time and again. Its presence, and attitudes toward it—the cultural stereotyping, cultural usage, cultural development—link one historical period, one civilization, to another, sometimes in the most surprising ways and very often flying in the face of all logic and common sense as well. One of the most intriguing aspects of the history of red hair is the way these links run on through time. You begin by investigating the impact of redheaded Thracian slaves in Athens more than 2,000 years ago and end at Ronald McDonald. You examine the workings of recessive characteristics and genetic drift in isolated populations and come to a stop at the Wildlings in Game of Thrones. You explore depictions of Mary Magdalene and find yourself at Christina Hendricks.

Why is the Magdalene so often depicted as a redhead? What possible reason can there be for that? If there ever was a specific individual of this name (which is a big assumption—the Magdalene as the Western church created her is a conflation of a number of different Biblical characters), her name suggests that she could have been a native of Magdala, on the western shore of the Sea of Galilee, well below the forty-fifth parallel. Beneath this latitude, redheads, while not unknown, are vanishingly rare, so the Magdalene’s coloring in Western art and literature is unlikely to recall some Biblical truth. What, then, for so many artists, from the medieval period onward, is the explanation for showing Mary Magdalene with red hair? What message did that convey to an audience five hundred years ago? What might it tell us about that audience? And what might it illuminate about our own attitudes toward red hair today?

To begin with, from my own experience in my student days of working as an artist’s model, I think artists simply enjoy depicting red hair. They like the turning shades and tints, they relish the glint and gleam of light upon it and the way that light bounces off the pale skin that so often goes with it. But the meaning of the red hair of the Magdalene takes one somewhere else altogether. It reflects the fact that the version of Mary Magdalene that the Western church has always found most fascinating is that of a reformed prostitute, a penitent whore, and culturally, for centuries, red hair in women has been linked with carnality and with prostitution. It still is today. What color is the hair of Helena Bonham Carter’s character, Red Harrington, in Disney’s 2013 film The Lone Ranger (and yes, there is a clue in her character’s name)? As flaming a red as Piero di Cosimo’s poised, calm, intellectual Magdalene of c. 1500, sat at her window, reading her book. Two entirely different women, centuries apart, yet linked by their societies’ identical responses to their hair color. And this leads back to one of the stereotypes that began this discussion, and back to one of the greatest contradictions in the cultural history of the redhead: the centuries-long linkage between red-haired women and sexual desirability, and the fact that (despite, at the time of this writing, the naturally red-haired Sherlock actor, Benedict Cumberbatch, being voted sexiest actor on the planet) the exact opposite seems to hold true for redheaded men.5

This book is a synoptic overview of red hair and redheadedness: scientifically, historically, culturally, and artistically. It will use examples from art, from literature, and, as we come up to the present day, from film and advertising, too. It will discuss red hair not just as a physiological but as a cultural phenomenon, both as it has been in the past and as it is now. Redheaded women and sex and the gendering of red hair is a subject to which it will return in detail, but this book will also journey through the science of redheadedness, its history and the emerging genetic inheritance that is starting to be understood by modern medicine today. It will examine the many conflicting attitudes toward the redhead, male and female, good and bad, West and East. It is a study of other, and as always, what we say about “other” is far less interesting than what that says about us. But if you are going to ask what and who and how and why, the place to start is where and when.

___________________

1 By comparison, somewhere between 16 percent and 17 percent of the population of the planet has blue eyes and 10 to 12 percent of the population is left-handed. Roughly 1 in 10 Caucasian men are born with some degree of color blindness, while 1.1 percent of all births worldwide are of twins. The incidence of albinoism, worldwide, is roughly 0.006 percent.

2 Bishop Cooper’s great work almost never saw the light of day at all. When it was half completed, Cooper’s wife (“a shrew,” according to that indefatigable chronicler John Aubrey), “irreconcileably angrie” with him for neglecting her in favor of his studies, broke into his study and threw his papers on the fire. Aubrey does not record if she was a redhead, too.

3 No one could write a book on redheads without a debt to Professor Rees and his research. I am very happy to record my gratitude to him for his early assistance and generous advice.

4 Saul Feinman and George W. Gill, “Sex Differences in Physical Attractiveness Preferences” The Journal of Social Psychology 105, no. 1 (June 1978): 43–52.

5Metro newspaper, October 3, 2013.

WAY, WAY BACK, MANY CENTURIES AGO

In solving a problem of this sort,the grand thing is to be able to reason backwards.

ARTHUR CONAN DOYLE, A STUDY IN SCARLET, 1887

The ur-redhead, the first carrier among early modern humans of the gene for red hair and thus the genetic grandparent of the vast majority of redheads now alive, appeared on this planet some time around 50,000 years ago.

The world, at this point, was a very different place from how it appears today. Those parts now dry and arid, such as the Sahara, were green and pleasant; areas we think of as temperate, including most of western Europe, were either tundra or under an ice sheet. Stomping or slinking across that ice sheet went the fantastic mega-fauna of the Later Stone Age, or Upper Paleolithic period—woolly mammoth, giant elks, two-hundred-pound hyenas, saber-toothed cats. Trailing after them went Europe’s resident population of Neanderthals, who had lived as hunter-gatherers in this landscape for 200,000 years; and creeping cautiously along as a distant and possibly rather puny-looking third came the first early modern humans.

These early humans had left Africa some 10,000 years before. They had already created populations in the Middle East and Central Asia; they were to explore around the coastlines of the Indian subcontinent; reach as far across the Pacific as Australia and as high as Arctic Russia; find toeholds in the Far East; and at some point cross the land bridge into what is now North America. Their expansion was driven (along with, one might suspect, hunger or greed) by an event referred to by paleontologists as the Upper Paleolithic Revolution. What this term encompasses is a step-change in toolmaking, from basic stone implements to highly specialized artifacts of bone or flint that range from needles to spearheads; evidence for the first purposeful engagement in fishing; figurative art, such as cave-painting, along with self-adornment and bead-making; long-distance trade or bartering between different communities; game-playing; music; cooking and seasoning food; burial rituals; and in all probability at this date, the emergence of language.

There is no one reason why this evolutionary jump happened when it did, nor even a consensus as to when or where it began. It may have been driven by changes in climate, as the ice sheets receded or grew, causing these early modern humans to create new technologies and survival strategies or perish. It may have been a very gradual process, but simply without a large-enough surviving debris field of earlier artifacts and evidence for us to be able now to judge how gradual; it might have been triggered by some sudden and singular genetic anomaly; or any possibility between these two. We simply don’t know; too much evidence has been lost to us. Melting glaciation and rising sea levels have drowned the evidence of the earliest coastal settlements. All trace of those who may have battled out a nomadic existence on the ice sheets has disappeared. What we do know is that some 40,000 to 35,000 years ago, those people who had settled the grasslands of Central Asia began to explore outward, west and north, working their way from Iran to the Black Sea, up the valley of the Danube, and into Russia and the rest of Europe. With them, along with their new technologies and beliefs and emerging ethnicities, they carried the gene for red hair.

This may come as a surprise. The gene for red hair, for pale skin, for freckles (on both of which more later), did not originate in Scotland, nor in Ireland, despite the fact that in both those places you will now find the highest proportion of redheads anywhere on Earth (Scotland leads the way with 13 percent of the population being redheads, and maybe 40 percent carrying the gene for red hair, while 10 percent of the people of Ireland have red hair and up to 46 percent carry the gene). Logically, the place with the greatest incidence of any particular characteristic would, one might think, be the place where it first came into being, but not in the case of red hair. The gene emerged at some point in time between the migration from Africa and the settling of those grasslands of Central Asia.

We’re able to make this assertion because of a superbly elegant hypothesis known to scientists as the molecular clock. This piece of evolutionary calculus uses the fossil record and rates of minute molecular change to estimate the length of time since two species diverged, charting this over thousands upon thousands of years, if need be. It enables us to calculate not only how long populations have been separate but how separate they are, with each change in an amino acid, or a DNA sequence, being a tick of the clock. Calibrated to the fossil record, the molecular clock makes it possible to estimate the point in geological history when new genetic traits first came into being. Such as, for example, red hair, or the gene for red hair at least, since at this point that is all we are talking about, the gene, rather than its expression, the appearance of red hair itself.6 And the reason for this lies in the fact that the number of individuals making these migrations seems to have been quite astonishingly low.

It’s been estimated that at the time of that final successful migration out of Africa 60,000 years ago, there may have been no more than 5,000 individuals in the entire African continent. The number estimated to have crossed from Africa over the then-shallow mouth of the Red Sea and into the Middle East, whose footprints now lie fathoms deep and whose descendants would become Homo sapiens, may have been no more than 1,000 and could have been as few as 150. There had been other migrations before this one—the fossilized remains of Java Man and Peking Man, or the 1.8-millionyear-old remains of Homo erectus recently discovered in Georgia represent earlier offshoots. The Neanderthal population of Europe is thought to have descended from another even earlier common ancestor, shared with early modern humans, maybe 300,000 years before. There may have been many other earlier migrations out of Africa that failed—just as there were many Roanokes before there was a single Pilgrim Father—or if they did not, their genetic traces are still too deeply hidden within us for science to be able as yet to make them out. But even without ice storms and blizzards of a ferocity that would make headlines in Siberia today, even without enormous carnivores, for this nascent population of early modern humans, the world was not only a staggeringly dangerous place to be, but one with precious few others of the species to share it with.7

And how do we know this? Because, despite the many variations in skin, hair, and eye color that loom so large for us, despite the many rich and challenging social and cultural differences across our planet, genetically we are so very undiverse.

Consider, for example, the heather, or Ericaceae. It colors the hillsides about my brother’s house on the Isle of Skye, fills cranberry bogs in Canada, and romps across the foothills of the Himalayas. Heather, cranberry, and rhododendron are all Ericaceae. There are 4,000 different species in total. You need many, many ancestors to create that much genetic divergence. Consider the dog, Canis lupis familiaris. There are nine separate breeds of dog, from wolves and jackals to man’s best friend, snoozing at your feet. The domesticated breed itself encompasses a spectrum of variation from dachshunds to bulldogs to Great Danes. Think how much genetic diversity that requires. Compared to the differences between a Chihuahua and a St. Bernard, what do we offer? Our limbs are always pretty much in the same proportion to the rest of our bodies, as are our facial features. Our skulls do not radically change shape; we do not come some with snouts and some not; our ears do not stand up or flop, or trail along the ground. Yet we have been breeding and interbreeding for millennia. The reason why there is so little differentiation between any one of us and every other one of us, compared to so many other species of fauna and flora, is because the number of genetically unique individuals the process began with was so mind-bogglingly small.8 And the one certainty about red hair is that for a red-haired baby to result, both mother and father have to be carrying the gene, and what is more, both have then to donate that specific recessive gene in sperm and egg. So if the gene for red hair was present in the early human population in the same percentage in which it is found today, with such tiny numbers of people spread out over such a huge area, it might have existed unseen, unsuspected, and unexpressed for generation after generation without any such propitious meeting taking place.

It must also be remembered that in discussing our ancestors of all those many millennia ago, almost nothing can be stated as irrefutable fact. There are a half dozen equally valid theories for every tiny piece of ancient evidence. Do we know, for example, that Homo sapiens was responsible for the extinction of all those giant animals and the disappearance of the Neanderthals? No, we don’t. We know that the arrival of one coincided with the disappearance of the other; we know, for example, that the last Neanderthals in Europe, who were physically far stronger and had bigger brains than the incomers who displaced them, had completely disappeared by 24,000 years ago, the last of them dying in remote caves facing the sea on the coast of Gibraltar. Looking at our more recent actions on this planet we may conclude that we’re a depressingly good candidate for the prime suspect; but the extinction of the cave hyenas and saber-toothed cats (circa 11,000 years ago), giant elk (7,000 years ago), the mammoth (the last herd lived on Wrangel Island, off Siberia, as recently as 1,650 years ago), and of the Neanderthals themselves could equally well have been caused by climate change or by disease as by the effects of our aggression or over-predation. Or it might have been caused by a combination of all these things. We simply don’t know.

All the same. We are an ambitious, covetous, exploitative, and destructive species, and there has rarely been much good in our engagement with anything we perceive as “other.” We interpret difference as threat rather than potential. And sadly, our race is not alone in that.

The El Sidrón caves are in northern Spain, inland from the coastline of the Bay of Biscay. The nearest large town is Oviedo. During the Spanish Civil War, the caves were used as hideouts by Republican fighters. They have always attracted the curious and intrepid, and when in 1994 what appeared to be two human jawbones were discovered in the gravel and mud on the floor of one of the caves, it was assumed that as the remains were in such good condition they were the tragic relics of some misadventure from the conflict of 1936–39—the victims of some forgotten Civil War atrocity.

The bones were indeed evidence of an atrocity, but of one much, much longer ago. The remains of twelve individuals—three men, three women, three teenage boys, and three children, including an infant—were those of an extended family group of Neanderthals who had presumably been ambushed outside the cave, killed, dismembered, and then cannibalized, the flesh removed from their bones with sharp flint knives, the long bones split to get at the marrow. It’s presumed they must have strayed into the hunting territory of another, rival group of Neanderthals and paid this dreadful price. Or perhaps conditions were so harsh it was a simple case of them or us. After their deaths, some event, perhaps a storm and flash flood, caused the roof of the cave in which their bones were found to collapse, washing their remains into the caverns, and thus they were immured together for another 50,000 years.

Any discovery of so much material in one place is of course of immense importance to archaeologists, but what makes the El Sidrón family so significant a find is just that: these individuals all seem to have been related to one another. They share no more than three groups of mitochondrial DNA, the type that is passed unchanged from mothers to children. In fact all three of the adult men have the same type. And so well preserved were the remains that forensic science could not only extract readable amounts of fragmentary DNA from them but could even fit individual teeth back into jaws. There are similar idiosyncrasies in dentition between the teeth and jawbones of different members of the group, and two of the men shared the same gene variant, which, it is thought, would have given them pale skin, freckles, and red hair.9

We all possess some DNA (maybe 1–4 percent) in common with Neanderthals, and presumably with that original common ancestor, all those many thousands of years ago. If you reach back in time, the percentage of Neanderthal DNA in modern humans seems to increase. Ötzi the Iceman, whose mummified body, frozen into a glacier, was found in 1991 in the mountains of the Austrian-Italian border and who died in about 3,300 BC, had more Neanderthal DNA than today’s modern humans. Not a huge amount (it’s been estimated at 5.5 percent), but a statistically significant one.10

It would be very neat, therefore, to assume that the gene for red hair as it is found in most redheads today is a Neanderthal characteristic, and that when the two species, Neanderthals and early modern humans, met and interbred (scientific thought goes back and forth on this point, but let’s assume usual things happen most usually), the gene was transferred over. It would be very neat; and given the redhead’s reputation for violent bad temper, it’s a theory that has given amusement and much satisfaction to many non-redheads since the first days of anthropological science back in the nineteenth century. It is still encountered time and again in discussions of red hair today, but it is also completely wrong. The genetic mutation that produced the red-headed men from El Sidrón is different from that found in redheads today. It is instead an example of a phenomenon where what appears to be the same result stems from very different causes—something else we will be encountering again. In any case, the far more fundamental point of interest with the red-headed Neanderthals of El Sidrón is not the hair—it’s the freckles. It’s the skin.

The gene that today results in the red hair of almost every redhead on the planet sits on chromosome 16, and if you have red hair, it’s because the version you have of that gene is not working as well as it might. Working perfectly, that MC1R gene, or melanocortin 1 receptor, to give it its full name, would give you brown eyes, dark skin, and an ability to withstand strong sunlight without developing sunburn, sunstroke, or worse. It would do this by stimulating the production of a substance called eumelanin, which colors dark skin, dark eyes, and dark hair. However, MC1R is fritzy. Like a bad internet provider, it flips in and out. If you have red hair, it is almost certainly (there are rare medical conditions that produce red hair, and in the Solomon Islands in the Pacific, an entirely different genetic mutation gives some islanders the most striking gingery-blond afros) almost certainly, therefore, down to the fact that you carry two copies of a specific recessive variant of the MC1R gene that dials eumelanin production (with all its protective benefits under strong sun) right down, replacing it with yellow or red phaeomelanin, in an extraordinarily complex set of variants that determines the color of individual hairs on your head and of individual cells in your skin.

MC1R, however, is not alone in this process. There is another gene, HCL2, on chromosome 4 (rather unpoetically, HCL2’s full name is simply “hair color 2 [red]”), that also contributes to red hair. Moreover (I did warn you this was complex), while red hair is indeed caused by a recessive gene, there are many possible variants, from recessive red to fully dominant brown or black, with an equal number of manifestations of so-called “codominance” in between.

Thus, many a blonde or brunette has freckles. Many brunettes also have a red tint to their hair, or rather, hair cells that are individually and one by one a mix of eumelanin- and phaeomelanin-producers. A man can have brown or blond hair on his head, yet a beard that grows in red (and very annoying some of them seem to find it, too). This pairing of, say, brown hair, freckles, and red beard is known as “mosaicism,” which describes it pretty much perfectly. You can have red hair in any shade from palest strawberry blond to deepest chestnut. It can come hand in hand, as it were, with blue/green eyes and pale skin and freckles, as it has with me, or with amber eyes, or hazel, or dark brown. A recent survey undertaken by Redhead Days, who run the largest annual festival of redheads in the world, uncovered the fact that up to a third of those who responded classified their eye color as hazel or brown. And (and this is where things get really interesting) it can come with skin dark enough to protect you from sun that would send many another redhead running for sun hat, sunglasses, and sunblock. In general, redheads and strong sun most emphatically do not mix. If you look back at the Redhead Map of Europe, at the beginning of this book, you will see how suddenly the incidence of red hair drops off below that forty-fifth line of latitude. But Afghanistan, Morocco, Algeria, Iran, northern India and Pakistan, and the province of Xinjiang in China all have ancient, native populations of redheads. Shah Ismail I (1487–1524), commander in chief of the Qizilbash and founder of the Safavid dynasty in Iran, was described by the sixteenth-century Italian chronicler Giosafat Barbaro as having reddish hair, and indeed his portrait in the Uffizi, by an unknown Venetian artist, shows a man with an aquiline nose, red beard, and red mustache. The sixteenth-century Shahnama of his Safavid successor, Shah Tamasp, now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, shows a red-bearded hero, Rustam. In the ancient world Alexander the Great’s Roxana, who was born in Bactria, now northern Afghanistan, and who the Napoleon of the ancient world married in 327 BC, was reputedly a redhead; the present-day Princess Lalla Salma of Morocco perhaps gives an idea of quite how beautiful she might have been. Then there is that different shuffle of the genetic pack in the Solomon Islands in the Pacific— which, again, comes with skin dark enough to withstand in this case tropical sun. (Fig. 29). In the history of red hair, what you might call its typical Celtic manifestation—pale skinned, blue eyed, suited for cool and rainy climes and cloudy skies—may not originally have been typical at all. In fact pale skin in early modern humans has been estimated as having appeared as recently as 20,000 years ago.11