10,00 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Ithaca Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

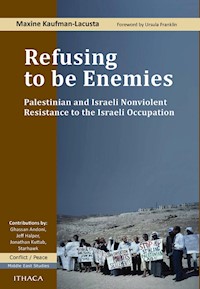

"Refusing to be Enemies: Palestinian and Israeli Nonviolent Resistance to the Israeli Occupation" presents the voices of over 100 practitioners and theorists of nonviolence, the vast majority either Palestinian or Israeli, as they reflect on their own involvement in nonviolent resistance and speak about the nonviolent strategies and tactics employed by Palestinian and Israeli organizations, both separately and in joint initiatives. From examples of effective nonviolent campaigns to consideration of obstacles encountered by nonviolent organizations and the special challenges of joint struggle, the book explores ways in which a more effective nonviolent movement may be built. In their own words, activists share their hopes and visions for the future and discuss the internal and external changes needed for their organizations, and the nonviolent movement as a whole, to successfully pursue their goal of a just peace in the region. A foreword on the definition and nature of nonviolence by Canadian author Ursula Franklin, analytic essays by activists Ghassan Andoni (Palestinian), Jeff Halper (Israeli), Jonathan Kuttab (a Palestinian activist lawyer with international experience) and Starhawk (an 'international' of Jewish background), and an epilogue from the author, round out the book. Andoni offers an analysis based on his long experience of nonviolent activism in Palestine, while Halper postulates 'Six Elements of Effective Organizing and Struggle' as a conceptual framework for the interviews. Kuttab argues that, even given the Palestinians' legal right to armed struggle, 'nonviolence is more effective and suitable for resistance', and Starhawk describes the unique challenges faced by Palestinian nonviolence.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Ähnliche

REFUSING TO BE ENEMIES

Palestinian and Israeli Nonviolent Resistance to the Israeli Occupation

MAXINE KAUFMAN-LACUSTA

With a foreword by Ursula Franklin

Foreword by Ursula FranklinJacket design by Garnet Publishing (photo by Maxine Kaufman-Lacusta)

Contents

FOREWORD

Notes

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

ABOUT THE CONTRIBUTORS

INTRODUCTION

Notes

PART I NONVIOLENT ACTION – FROM PERSONAL CHOICE TO POLITICAL STRATEGY

1 WHY NONVIOLENCE? WHY ANTI-OCCUPATION ACTIVISM? PERSONAL RESPONSES

Notes

2 NONVIOLENCE IN THE STRUGGLE AGAINST THE OCCUPATION

Notes

PART II STRATEGIES AND APPLICATIONS OF NONVIOLENT ACTION

3 NONVIOLENT STRATEGIES OF PALESTINIAN AND ISRAELI ORGANIZATIONS

Notes

4 JOINT STRUGGLE AND THE ISSUES OF NORMALIZATION AND POWER

Notes

5 THREE NONVIOLENT CAMPAIGNS: A CLOSER LOOK

Notes

PART III LOOKING FORWARD

6 TOWARDS A MORE EFFECTIVE NONVIOLENT MOVEMENT

Notes

7 LEARNING FROM THE PAST, BUILDING FOR THE FUTURE

Notes

8 THINKING ABOUT THE FUTURE OF PALESTINIAN NONVIOLENT STRUGGLE

Notes

9 LOOKING AHEAD

Notes

PART IV ANALYSIS

10 PALESTINIAN NONVIOLENCE: A HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE

Note

11 TOWARDS A STRATEGIC NONVIOLENCE

12 PALESTINIAN NONVIOLENCE: A PACIFIST PALESTINIAN PERSPECTIVE

13 THE UNIQUE CHALLENGES OF PALESTINIAN NONVIOLENCE

Notes

14 CONCLUSIONS

Notes

15 EPILOGUE

Notes

16 AFTERWORD

Notes

WORKS CITED

USEFUL WEBSITES

FOREWORD

This is an important book. Its significance goes well beyond the task of documenting a greatly underestimated facet of the present tragic struggle in Israel/Palestine.

Embedded in the chronicle of remarkable people and events, readers will discover the emerging characteristics of nonviolent responses to strife and injustice in a technological world. Each activity documented in this book is not only an account of a specific event or situation, but also an illustration of an often novel and significant development within global patterns of nonviolent strategies.

To help readers to appreciate both the general and the specific attributes of nonviolent activities is not an easy task, particularly in the binary mindset of the current political discourse with its “yes or no,” “in or out,” “ally or adversary” modes.

To begin with, there is genius as well as problematique in the very term nonviolence. Resisting force and changing power structures by ways and means that are defined by what they are NOT seems to be vague and indecisive at best. However, nonviolent approaches provide, and have provided, some of the most creative, helpful and lasting social changes, often because the approaches have been situational, site specific, and grown out of practice and have mixed ordinary life skills with extraordinary unconventionality.

It has been pointed out frequently1 that, throughout human history, nonviolent conduct is the normal and expected pattern of social interactions; cooperation and recognition of the needs of others are the given and for this very reason, it is the violent response, the abnormal, that is recorded, analyzed and taught (see also Kuttab later in the book).

What, then, do we mean when we speak of nonviolence? At this point, attention to definitions may be helpful.In terms of the issues addressed in Refusing to be Enemies, “violence” is most usefully defined as “resourcelessness,” surprising as it may sound. Yet reliance on one single resource; i.e., the ability to destroy, to inflict harm, is in the final analysis the most telling attribute of violence.

Organized violence—armed force—is frequently the preferred tool of the powerful. It seems so straightforward: nothing more than the translation into daily reality of a threat, “Do as I say, or else …” when “or else …” means inflicting destruction, harm and hurt.

While the powerful can command many resources other than force and sophisticated systems of inflicting harm, the oppressed, the powerless, cannot. They may have exhausted the resources within their reach and may therefore fall back on violence from a genuine feeling of being deprived of other resources to address their needs.

Once we recognize violence as resourcelessness—by choice or by perceived necessity—the nature of “nonviolence as resourcefulness” comes into focus. The belief in and the respect for a common human creativity and worth become the resource base from which nonviolent actions can arise. The understanding of nonviolence as resourcefulness thus provides a guide for the mobilization of human and social resources but not a template.

It is my hope that the foregoing thoughts and definitions will illuminate the universal components that link the nonviolent actions documented in this “case book” to past and future nonviolent responses.

Ours is a complex global society, in which unforeseen and unforeseeable instruments of power, control and interaction are emerging at rapid rates. These new power structures are frequently superimposed on traditional arrangements and habits of political and social conduct. Such new developments, often related to modernization and globalization, are altering individual and collective behaviours and a society’s sense of belonging and responsibility.

These new features of our interdependent global world are shaping the nature and the conduct of conflicts. On the one hand, the range, force and sophistication of violent actions have increased beyond imagination; on the other hand, the same modern technologies have increased the flow of information, of goods and people, obliterating many physical, legal and emotional boundaries, often the very boundaries that have previously confined the range of organized violence.

New reasons for conflicts, be they military or civilian, commercial or ideological, have arisen as a consequence of the ascendance of technological societies. These conflicts, in turn, are often characterized by very different patterns of conflict resolution and altered notions of territory and boundaries. Yet the ancient notion of “The Enemy” has remained part of the modern world’s social and political paraphernalia.

As a category, “the enemy” is significantly different from seemingly related social classifications such as “foreigner,” “stranger” or persons “from away.” Assigning the designation “enemy” to some people goes well beyond emphasizing a distinction between “them” and “us.” The enemy label becomes a coordinate that places and defines the holder within the realm of an existing or implied conflict.

As a class, enemies are deemed to be intrinsically hostile to one party in the conflict, regardless of personal conduct or conviction, merely by virtue of their belonging to a particular group. Kenneth Boulding, in Conflict and Defense,2 defines parties in conflict as “Behavioral Units.” Members of such units—nation-states or clans, organizations or churches—are assumed to exhibit the same behaviour with respect to a conflict that impacts them.

Boulding’s definition is applicable to principled as well as more casual situations. Thus pacifists expect conflict when they refuse military service; vegetarians may risk social discord when declining to eat meat at a party. Both pacifists and vegetarians choose their respective behavioural units, often in full knowledge of possible conflicts. The designation of “enemy,” however, is not self-selected. It is a label bestowed by the opponent.

Moving one’s adversaries into the enemy class can be politically helpful. To quote Boulding again, “[A] strong enemy is a great unifying force; in the face of a common threat and the overriding common purpose of victory or survival, the diverse ends and conflicting interests of the population fall into the background and are swallowed up into the single, measurable, overriding end of winning the conflict.”

Not only can the presence of “enemies” serve as social glue, their presumed evil intent and unbending hostility can become the justification for otherwise unacceptable actions against them. Once one appreciates the deep social roots of the concept of “The Enemy,” it becomes clear that, for individual citizens, refusing to be enemies is a profoundly political act. This act denies the ruling apparatus of all groups involved in a particular conflict the right to label and assign individuals to a particular behavioural unit.

I can not overemphasize the importance of this act. It entails the crucial paradigm shift that can break the stranglehold of violence and open the option of nonviolent action. Nonviolence, after all, is not a bag of tricks to be pulled out if or when violent responses are not possible. Nonviolence is a set of collective insights that, by calling on the human potential of victim and perpetrator alike, opens ways to oppose violence and oppression that are different in kind from the blind tit-for-tat of organized violence.

The events recounted and ideas articulated in this book make it clear that nonviolent strategies are not soft or mushy. Their hard political edge is clear and visible. The goal of the interventions is to decrease suffering and to achieve justice, BUT the changed situations can only be lasting and functional if they assure justice for all. This means that the transformations that specific nonviolent interventions try to achieve must, in the end, yield systemic changes. Those on the ground who constitute the nonviolent movements know this, as they develop their visions of human betterment—to use Boulding’s term.

Bertolt Brecht was part of the struggle against the rise of fascism and the rising tide of violence in his time. He wrote in 1935, well before the birth of most of those whose voices this book has captured, on community responses and on the distinction between help and systemic change.

What End Goodness3 Bertolt Brecht, translated by Scott Horton1. To what end goodness If the good are immediately struck down, or those To whom they are good Are struck down?

To what end freedom If the free are forced to live among the unfree?To what end reason If only stupidity puts the bread on the table That each of us needs? 2. Instead of just being good, make an effort

To create the conditions that make goodness possible, And better still That make it superfluous!

Instead of just being free, make an effort To create the conditions that liberate us all, And that make the love of freedom Superfluous!

Instead of just being sensible, make an effort To create the conditions that make the stupidity of the individual Into a bad deal!

Were he with us today, Brecht would convey his friendship and respect to those whose actions and thoughts this book records. He would be grateful for their courage and creativity as they explore the resource base of nonviolence. He would see, as I do, the bridge across space and time built by all those who, in refusing be enemies, try to build for all a livable world.

As I said at the onset of this foreword, this is an important book. May it be well read.Notes

1 Sibley, Mulford Q., ed. 1963. The Quiet Battle. Garden City, NY: Anchor Books, Doubleday & Company.2 Boulding, K. E. 1963. Conflict and Defense. New York: Harper and Row.3 Brecht, Bertolt. 1935. “Was nützt die Güte,” in Gesammelte Werke, Vol. 4, p. 553.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I want to express my gratitude and appreciation to the many people who have inspired and supported me in this project. My thanks especially to Ursula Franklin and the contributing authors, as well as the hundred-plus interviewees for this book—including those who, for reasons of space or difficulties with translation, or because their comments somehow fell outside the arbitrary parameters of the present book, were not included: Anton Mura, youth worker at the AEI, Dr Mahmoud Nasr and Dr Abu Hani of Nablus Health Care Committee, Eileen Kuttab of Birzeit University Women’s Studies Department, Hava Keller of Women for Women Political Prisoners and Windows, Hisham Jamjoum of ISM, Arabiya Shawamreh and Nada B’dou, Beate Zilversmidt, David Nir, and Edy Kaufman.

This book would not have been written, or probably even conceived of, were it not for the many activists who gave willingly of their time and insights for earlier projects—Creative Resistance (1993) and before that, Curse Not the Darkness, “the book that never was,” for which I interviewed several dozen activists in the mid-eighties. Many of these early interviewees became friends and colleagues, some appear in the present book, and all of them have been an ongoing source of inspiration. Some appear, as well, in Israeliens et Palestiniens: Les Mille et Une Voix de la Paix, by Danielle Storper-Perez (Cerf, 1993). My thanks to Danielle for treating me as a colleague and including me in her project, despite my mismatched academic background.

I owe a particular debt of gratitude to several people who believed in my ability to get this book written, and encouraged me even when I doubted myself: Reed Malcolm, who gave me encouragement even while gently rejecting a very early draft manuscript; Kevin Burns, who suggested I approach Ursula Franklin to write a foreword and clued me in to ways to articulate some of my own interpretations of the material; Maia Carter Hallward, whose invitation to participate in her panel on Identity Politics and the Boundaries of Israel and Palestine at the 2007 annual meeting of the Middle East Studies Association (MESA) pushed me to write the paper that provided the basis for my conclusions and epilogue; and activist-academic Denise Nadeau who goaded me to choose a title and encouraged me to join Maia’s panel despite my lack of academic credentials in the field. My thanks, too, to the Palestine-Israel Journal of Politics, Economics and Culture for allowing me to reproduce in this book a number of ideas and suggestions that were first published in PIJ (Kaufman-Lacusta 2008) in an article based on the MESA paper, and to the Canadian Friends Service Committee for grants towards my travel to Israel and Palestine on two occasions.

Jeff Halper deserves special mention. Besides being an eminently quotable interviewee and speaker, and sharing his analysis and strategic thinking in a contributed chapter, he also helped me enormously in deciding how to arrange the material, and provided invaluable feedback at various stages.

I’d also like to thank Dan Nunn, my editor at Ithaca Press, who provided expert and knowledgeable editorial guidance with a gentle hand that took much of the pain out of the difficult necessity of extensive cuts to the original overly long manuscript. His flexibility and patience have made him a joy to work with.

I’d like to dedicate this book to the memory of my dad, Jack Kaufman, for the example of his sense of social justice and of the need to do more than just talk about it, and to some wonderful people who did not live to be interviewed for it: Yochanan Lorwin of the Alternative Information Center, Mary Khas of the AFSC preschool program in Gaza City, Arna Mer Khamis of Care and Learning in Jenin, Shlomo Elbaz of The East for Peace, and Toma Sik of PINV and WRI and much more.

Last, but definitely not least, I want to thank my loving and supportive husband, Michael, whose suggestions for radical rearrangements, although invariably greeted with stubborn resistance on my part, almost always resulted in significant improvements to the book.

ABOUT THE CONTRIBUTORS

Ghassan Andoni is a long-time nonviolent activist and academic (Physics) at Birzeit University. An active participant in the Beit Sahour tax strike during the First Intifada, he co-founded the Palestinian Center for Rapprochement between People (1988) and the International Solidarity Movement (2001), as well as the Alternative Tourism Group and the Applied Research Institute – Jerusalem. Recent writings include “A Comparative Study of Intifada 1987 and Intifada 2000” in Roane Carey (ed.), The New Intifada: Resisting Israel’s Apartheid (Verso Books, 2001), and (with Renad Qubbaj, George N. Rishmawi, and Thom Saffold) a chapter on International Solidarity in Stohlman and Aladin, Live from Palestine: International and Palestinian Direct Action Against the Israeli Occupation (South End Press, 2003). He was also part of the editorial team for Sandercock, et al., Peace Under Fire: Israel/Palestine and the International Solidarity Movement (Verso, 2004).

Ursula Franklin was the first woman professor in the Department of Metallurgy and Materials Science at the University of Toronto (1967) and the first woman to be named University Professor (1984), the highest honour given by that institution (now Emerita). She is a long-time member of Canadian Voice of Women for Peace and is one of Canada’s foremost advocates and practitioners of pacifism. Franklin continues to work for peace and social justice, to actively encourage young women to pursue careers in science, and to speak and write on the social impacts of science and technology. She is the author of The Real World of Technology (1990, revised 1999), based on her 1989 Massey Lectures on the subject. Her most recent book is The Ursula Franklin Reader: Pacifism as a Map (Between the Lines, 2006).

Jeff Halper is coordinator of the Israeli Committee Against House Demolitions (ICAHD) and a professor of Anthropology. He moved to Israel in 1973 from the United States and was employed by the Jerusalem municipality for more than a decade, as a community worker in poor Mizrahi Jewish neighbourhoods. He also served as the chairman of the Israeli Committee for Ethiopian Jews. Halper has taught at universities both in Israel and abroad, including Friends World College—teaching at FWC centres in Jerusalem, Costa Rica, and Kenya and directing the Friends World Program at Long Island University, in New York State in 1991–93. He is the author of (inter alia) Obstacles to Peace, a resource manual of articles and maps on the Israeli/Palestinian conflict published by ICAHD, and An Israeli in Palestine: Resisting Dispossession, Redeeming Israel (Pluto Press, 2008).

Ghassan Andoni and Jeff Halper were jointly nominated for the 2006 Nobel Peace Prize by the American Friends Service Committee.Maxine Kaufman-Lacusta is a Quaker-Jewish activist who lived in Jerusalem for seven years (1988–95), during which time she participated in a variety of anti-occupation and solidarity groups, with a particular concern for the practice and promotion of active nonviolence and joint Israeli-Palestinian endeavours. A founding member of the Action Committee for the Jahalin Tribe (ACJT) and a participant in the Hebron Solidarity Committee, Maxine was also part of a small collective that offered nonviolence training workshops during the early and mid-nineties attended by Jewish, Palestinian, and Druze activists in Israel, as well as one for the ACJT. She served a total of twelve years on the Canadian Friends Service Committee and is currently an associate member for Middle East projects. She stands with Vancouver Women in Black and has published a number of articles on Palestinian and Israeli nonviolent activism and related topics.

Jonathan Kuttab has practiced law in Palestine, Israel, and New York State. His activism spans the realms of human rights, social, and church advocacy, and he has written and lectured extensively. He was a founder of Al Haq (the first human rights organization in the occupied territories), the Mandela Institute for Political Prisoners, the Palestinian Center for the Study of Nonviolence in Jerusalem, and Human Rights Information and Documentation Systems (HURIDOCS), Switzerland, and remains active in many of these, as well as in Nonviolence International and Sabeel-Palestinian Liberation Theology Center. His writing includes co-authorship of West Bank and the Rule of Law (ICJ, 1980), and he supervised a team of field workers and researchers who published two book-length reports on the human rights situation in the West Bank: Punishing a Nation (LSM/Al Haq, 1988) and Nation Under Siege (LSM/Al Haq, 1989).

Starhawk is a committed global justice and peace activist and the author or co-author of ten widely translated books. Webs of Power: Notes from the Global Uprising, which won a 2003 Nautilus Award, is a collection of many of her political essays. She made four visits to the occupied territories with the International Solidarity Movement, and essays written on or about those visits can be viewed on the Israel/Palestine page at www.starhawk.org. Starhawk offers training in nonviolent direct action and permaculture, a system of ecological design, internationally, as well as workshops on feminist and earth-based spirituality. On March 16, 2008, she was refused entry to Israel while on her way to Palestine to give a permaculture workshop.

INTRODUCTION

In 1993, while working as a Hebrew-to-English translator in the Jerusalem office of the Alternative Information Center (AIC), I compiled Creative Resistance, a short, interview-based book describing examples of nonviolent action by Israeli and joint Israeli-Palestinian groups. Creative Resistance was published by the AIC, itself a joint Israeli-Palestinian venture, and its target audience was Israeli and Palestinian peace/justice/ human rights activists. In those days, few activists in either Israel or Palestine used the word “nonviolence” or thought of their actions in such terms. Indeed, many assumed that nonviolence was by definition passive. My not-so-hidden agenda at that time was, on the one hand—in that pre-email era—to encourage greater sharing of information amongst groups and organizations that were engaged in activity that I (though not necessarily they) would define as “active nonviolent resistance” and, on the other hand, to perhaps contribute to an increased acceptance of the concept of nonviolent action on the part of people who were already practicing it, along with an appreciation of its potential and a sense of connection to the world-wide nonviolent resistance movement.

Unlike its predecessor, Refusing to be Enemies is not intended primarily for activists. The target audience for Refusing to be Enemies is the broader public, much of which is still relatively uninformed on the subject of nonviolent activism in the context of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and especially regarding its widespread use by Palestinian groups now and in the past. Also new is the present book’s elaboration of ways in which Palestinian-Israeli joint activism is pursued as a strategy for nonviolent resistance to the Israeli occupation, and its focus on attitudes towards the dynamics of, and the prospects for the future of, this form of struggle.

The interviews that make up the “meat” of this book took place, with a few exceptions, during three visits to Israel/Palestine, in September/October 2003, December 2005/January 2006, and April 2007.1Early on the first trip, I met with my Palestinian editorial partner, Ghassan Andoni, and with George N. Rishmawi, both of the Palestinian Center for Rapprochement between People (PCR), to formulate a set of interview questions. A week or so later, my Israeli editorial partner, Jeff Halper of the Israeli Committee Against House Demolitions (ICAHD), joined the project and has since given me much invaluable guidance in the shaping and execution of this book. Both Ghassan and Jeff have also contributed—in addition to their interviews and advice—chapters to the Analysis section of this book. Ghassan and George also set up meetings for me with the first of my Palestinian interview subjects.

After just a few days of interviewing, mainly in the West Bank, I was hugely impressed by the number and variety of consciously self-aware nonviolent activists I had met—students and teachers, Muslims and Christians, veteran activists and newcomers to nonviolence, former fighters, those for whom nonviolence was a tactical/strategic choice, and those for whom it was a way of life. Equally heartening was the surprising amount and variety of joint action with Israelis, ranging from the preparation of coexistence and mutual understanding curricula for use in schools in both jurisdictions, through the organization of joint demonstrations and direct actions (removing roadblocks, picking olives, blocking the apartheid wall, etc.), to the tackling of shared environmental concerns together, with the blessing of both Israeli and Palestinian Authority (PA) ministries.

Based on these impressions, I decided that the book should highlight the virtually unknown Palestinian nonviolent movement, rather than give an overview of Palestinian and Israeli nonviolent activism, as had been my original concept. Therefore, in consultation with Ghassan and George, the primary focus of the project was shifted to the immense range and variety of Palestinian nonviolent activism. This meant that, on the whole, I would limit my choice of Israeli interviewees to those who were (or had been) active in the occupied territories or in some other way (such as military refusal), and who had had a direct impact on the struggle to end the occupation and its excesses. As I wrote in my trip diary on September 25, 2003, “[T]he point that we most need to convey with this book has to do with the Palestinians’ side of the nonviolence story. The rest of the players are ‘supporting cast,’ vital as their work may be,” and this perspective has informed the project from that point onward.

One outcome of this shift of emphasis was that the subtext of the first interview question (“Why did you get involved in anti-occupation activism? Specifically, what brought you to nonviolence?”) was different for the two groups of interviewees. From the Palestinians I was seeking primarily to hear the reasons why they had chosen nonviolence rather than (or after personally rejecting) some other form of struggle, whereas the emphasis of my question to the Israelis was more along the lines of, “How did you come to support the Palestinian nonviolent struggle?” This resulted in very different “flavours” to their respective responses and, I’m afraid, unintentionally deprived some Israeli interviewees (e.g., Amos Gvirtz, a lifelong pacifist and advocate of “principled” [Gandhian] nonviolence) of the opportunity to express their choice of nonviolence in personal terms.

Nonetheless, I hope that “hearing” the many Palestinian and Israeli—Jewish, Muslim, and Christian2—voices of the interviewees will contribute to an understanding that what is often misperceived as a clash of cultures and religions is much more a matter of the politics and economics of conflicting nationalisms and land claims in an environment of underlying fears and misunderstandings—a situation where nonviolent activism may well be the only form of resistance that can realistically be expected to bring together members of both nations and of all the local religious communities.3

Finally, it is my hope that readers will come away from this book with a heightened sense of the widespread practice of, and support for, nonviolence amongst both Palestinian and Israeli anti-occupation activists, as well as of how the various forms of joint struggle are increasingly bringing together people of diverse beliefs, faiths, and cultures, uniting them in the common purpose of ending the occupation by nonviolent means.

Refusing to be Enemies is divided into four parts. The first three parts consist primarily of material selected from interviews and public presentations by a total of 115 contributors. My introductory and connecting comments are intended to provide context and indicate the relationships between contributors, so as to paint an overall picture while leaving in-depth analysis to Ghassan Andoni, Jeff Halper, Jonathan Kuttab, and Starhawk, whose essays—along with my conclusions and epilogue—make up the fourth part of the book.

Part I of the book moves from questions of personal choice to more theoretical considerations regarding nonviolence. In Chapter 1, some two dozen interviewees speak about how they came to choose nonviolence and/or what drew them to anti-occupation activism in general. Chapter 2 begins with descriptions from five interviewees of their activism going back to the era of the First Intifada (1987–93) and before. This is followed by reflections on nonviolence by three local activists and U.S. theoretician Gene Sharp—with emphasis on its relationship to the anti-occupation struggle.

Part II looks at the practice of nonviolence, focusing on strategies employed by nonviolent organizations in the context of resistance to the occupation. It starts with an examination of the choice of nonviolence as an organizational strategy and Palestinian and Israeli activists’ descriptions of the groups with which they work and of their activities and strategies (Chapter 3). In Chapter 4, one particular strategy—Palestinian/Israeli joint activism—is explored, beginning with descriptions of joint organizations and strategies and going on to explore attitudes toward, and power dynamics of, this form of activism. In Chapter 5 we take a closer look at three nonviolent campaigns with a significant joint-activism component: the First-Intifada-era tax strike in the town of Beit Sahour, the struggle against Israel’s separation barrier/apartheid wall as a focus for joint activism, and the years of nonviolent joint struggle in the village of Bil’in against construction of the wall and a settlement “neighbourhood” on land confiscated for this purpose.

Part III, “Looking Forward,” begins with a chapter asking how a more effective nonviolent movement might be built, and in particular, what activists feel needs to change in order for their organization—and the nonviolent movement as a whole—to more successfully pursue their goals (Chapter 6). In Chapter 7 we take a look at which nonviolent strategies and tactics have been effective thus far, go on to focus on the important strategy of military refusal, and review some important trends in Palestinian nonviolence. In the last two chapters of Part III, interviewees discuss their hopes and thoughts regarding the future of Palestinian nonviolent struggle, and share their visions for the future of the region itself.

Part IV begins with analytic essays by book-project partners and 2006 Nobel Peace Prize nominees Ghassan Andoni and Jeff Halper; by Jonathan Kuttab, a passionately pacifist Palestinian lawyer; and by feminist author and nonviolent activist-theorist-trainer Starhawk. Andoni’s piece offers an analysis based on his long experience of nonviolent activism in Palestine, while Halper’s chapter postulates six necessary components of an approach to nonviolence that goes beyond the simply tactical—integrating material from the book’s interviews so as to give a summary, focus, and analysis to the often free-ranging discussion with the many activists interviewed. Kuttab argues that, even given the Palestinians’ right—under international law—to armed struggle, “nonviolence is more effective and suitable for resistance.” Finally, in her essay, Starhawk discusses some of the unique challenges faced by the Palestinian nonviolent movement. The book ends with my conclusions on the subject of Palestinian/Israeli joint struggle, including future prospects and some thoughts about additional forms that the Israeli component of this struggle might take, and an epilogue examining the latter in greater depth.

Maxine Kaufman-LacustaNotes

1 I use the words “interview” and “interviewee” here and throughout the book loosely, since twelve “spoke” only through their conference talks and one primarily through written comments. The interview and presentation excerpts have been placed in contexts determined largely by what questions of mine they are responding to, and I have indicated when a given excerpt is from something other than an interview. I have edited the excerpts for clarity and “flow,” but not with any intent to alter meaning. Ellipses and rearrangements have generally not been noted, in the name of simplicity (the exception being inclusion of ellipses in excerpts from published material), and I apologize if my editing has unwittingly led to distortion. I sincerely hope it has not. As mentioned, my introductory and connecting comments are intended to clarify context and to indicate relationship among contributions, and so to contribute to an overall picture, while leaving in-depth analysis to Andoni, Halper, Kuttab, and Starhawk in Section IV. Organizational affiliations and positions attributed to interviewees are generally as of time of interview. In a few cases, where more recent information is available, it is noted as well.2 I must apologize at the outset for the absence in this book of any Druze interviewees. For a sympathetic and thoughtful description of the nonviolent struggle of the Druze of the Golan Heights, please see Kennedy and Awad 1985. Creative Resistance contains an account of draft resistance among the Israeli Druze, based on an interview with Druze Initiative Committee spokesman Ghalib.3 Despite the fact that many, if not most, of the interviewees you will meet in these pages consider themselves non-religious, even the most secular Israelis and Palestinians, when asked, will tend to identify with one of the local religious communities.PART I NONVIOLENT ACTION – FROM PERSONAL CHOICE TO POLITICAL STRATEGY

1 WHY NONVIOLENCE? WHY ANTI-OCCUPATION ACTIVISM? PERSONAL RESPONSES

I absolutely believe in nonviolent resistance as the only way to go. I think violence just begets more violence. There’s no guarantee that nonviolent resistance is going to achieve anything, but violent resistance achieves the opposite of what you’re trying to do. I wasn’t just morally opposed to violence; even tactically I think it doesn’t work.

This chapter is based primarily on my interviewees’ personal responses to two questions: “What brought you to nonviolence?” and “What made you decide to become an anti-occupation activist in the first place?”

Whereas I asked the second question of virtually all the activists I interviewed for this book—hoping to learn something about their personal motivations above and beyond the political impetus for their activism—the first, regarding the choice of nonviolence, was aimed principally at the Palestinian interviewees (all of whom were in some way engaged in nonviolent resistance), as well as those Israelis personally engaged in nonviolent actions of various sorts (as opposed to those in a more indirect support role). I wanted to know what had brought them to choose this—often hazardous, sometimes illegal—approach. The chapter includes, along with a selection of replies to the second question, a varied sampling of responses to the personal, as opposed to the organizational, side of the first. I was surprised to learn, for example, that some of the Palestinians with the strongest ideological—as opposed to simply tactical—commitment to nonviolence were ex-fighters or former supporters of armed struggle.

Many interviewees, particularly Israelis, made no mention of specifically “choosing nonviolence,” the nonviolent nature of their actions—which often bring them into direct defiance of the occupation authorities—being taken as a given. None of the Israelis I interviewed advocated the use of violence by themselves or other Israelis, although a few of them felt that Palestinian use of violent means to oppose the occupation was an unfortunate necessity. Indeed, relatively few of those I interviewed, Israeli or Palestinian, condemned all violence. While stressing their personal abhorrence of bloodshed and their (and their organizations’) choice to act nonviolently, many, especially among the Palestinian interviewees, were careful to make it clear that they recognized the right (under international law) of Palestinians, as of all oppressed peoples, to use whatever means were at their disposal to resist the occupation. Similarly, the bulk of Israeli military refuseniks would be willing to fight if they felt that to do so were truly required for the defence of their country.

Why Nonviolence?

Life-long Proponents of NonviolenceNuri el-Okbi Nuri el-Okbi, a Palestinian Bedouin with Israeli citizenship,1 has spent decades advocating for the rights of his people. Although not the only Palestinian citizen of Israel represented in this book, because of limitations of space and scope, he and Leena Delasheh of Ta’ayush are the only ones to articulate that point of view explicitly. The el-Okbis, along with most of the Bedouin in southern Israel, were evicted from their tribal lands in the early 1950s and relocated to an area of the northern Negev referred to as the sayag (reservation), with the assurance that they could return home in six months, a promise that has yet to be kept. For many years Nuri el-Okbi lived with his wife and children in the mixed Arab-Jewish town of Lod in central Israel and earned his living running an automotive garage. During that time he also founded the Association for the Support and Defence of Bedouin Rights and campaigned tirelessly on behalf of the el-Okbi tribe and other Negev Bedouin. Over the years, el-Okbi has carried out many Gandhi-like nonviolent actions, his latest being to maintain a constant peaceful presence on the tribal lands. When I interviewed him on April 24, 2007, he had been camping there for months, within sight of the tree under which his mother bore him over sixty years previously; he had been detained by the police several times, and had one arm in a cast thanks to rough treatment during his most recent arrest. I asked him why he had chosen this particular method of pursuing his cause, and he replied, “Because I first of all believe in nonviolence, and I am opposed to any violence.” He continued:

One who is right does not need to use violence. Its truth is very strong. Secondly, it’s my character. I can’t have anything to do with violence. I’m against violence, I call for nonviolence. I say that every drop of blood that is spilt is a sad waste. For many decades we’ve been suffering, and I believe that no problem can be solved by violence, by force. So I’m trying to find the path through which I can obtain the rights [for the tribe] without causing harm to any human being, to any interest [and] without getting involved in violence. This is very important. I think that human beings are forbidden to use violence.

“It’s not that I learned at university that it’s forbidden to get involved in violence,” concluded el-Okbi, “but I believe that a person who has sense and has a mouth and can speak, that’s stronger than using force and violence.”

Jean Zaru Jean Zaru, a Palestinian Quaker from Ramallah in the West Bank, referred explicitly to her choice of nonviolence as being faith-based. She described the concept of sumud (steadfastness)—“staying on your land, no matter what, and trying to affirm life in the midst of structures of death and domination”—in terms of “trying to do what God requires of you in these times.” “I think that is a nonviolent way of activity,” she told me.2 She added:

Many Palestinians have chosen the nonviolent struggle out of a faith base, because they feel that all of us are created in God’s image and to harm this image—or the dignity of any people—is really doing something wrong. Others find that strategically, with the imbalance of power, using military means is not helpful in our struggle. I don’t mean just the imbalance of power between the Israelis and the Palestinians on the level of military equipment and nuclear weapons and so on. It is also the media in the West that have unfortunately played a big part to present the Palestinians struggling for freedom and self-determination as terrorists, and this image should change.

“The structures of violence are silent,” Zaru stressed, “and people cannot take pictures of those.”

I think people should wake up and also try to analyze the structures of domination and violence in societies, whether economic, social, political, religious, or environmental. On the religious level, you have fundamentalist movements from the Jewish and Muslim, and the Christian Right of the U.S. that is very exclusive, nationalistic, chauvinistic, against the emancipation of women, and also against any peace solution.

Terming “unacceptable” the “use [of ] biblical words to justify oppression and dispossession and the building of settlements and oppression of other groups,” she stated, “I would rather like to look at the liberating aspects of faith, of all faith traditions, and see how they can help us, sustain us to really go on working for the reign of God in this world—a reign that does not encourage the structures of injustice and domination and violence.” Jean Zaru taught at the Friends Schools in Ramallah for many years, and told me how she had integrated a form of nonviolent resistance into her Home Economics classes in the early years of the occupation—in a desire “to give people hope that they can make a difference, no matter how small.” “I taught the girls,” she said, “how would you live responsibly to the Palestinian—or to the world— community as a Palestinian young woman” through their choices of what foodstuffs or clothing to purchase, for example—“not buying South African goods, but also not buying Israeli goods. And it is more ecological when you don’t buy all the industrialized things. It’s helping the simple farmers to survive, buying their products.”

In terms of responses to the “long, long occupation and dispossession and very difficult economic situation, the closures, and so on,” Zaru described nonviolent resistance as the “the only way of affirming life and dignity,” of keeping hope alive.

Some are tired, and they have withdrawn, either by leaving or by withdrawing into themselves and not being part of resisting these structures. There are some people who try to accommodate. There are some who try to manipulate the system. But all these groups do not bring any transformation to improve the situation. And there are groups who have chosen nonviolent resistance.

Citing the prophetic tradition, “where they spoke so much against evil in society and they wanted it to be changed, and people should have more righteousness and more right relationship with one another,” Zaru continued, “So resistance is legitimate, and nonviolent resistance is even better, which is the most important and only choice for me from my faith base.”

I think any faith that values life should really work for nonviolence, because I think violence dehumanizes both societies, the powerful and the powerless. And we have to work together to find the way out of this. Nonviolent resistance is the only way to bring transformation. I wouldn’t say that it’s easy. I wouldn’t say that people will not suffer. I wouldn’t say that it might stop the wall. But it starts a discourse that we are not ready to accept this any more. This is not fair and this is not acceptable. And then people would not feel hopeless and useless, that they cannot make a difference and then they stop making a difference in society. So that’s why nonviolent resistance is important, rather than complying or accommodating or withdrawing or manipulating.

Amos Gvirtz Amos Gvirtz is not himself religious, having been born and raised on the secular Kibbutz Shefayim, where he still makes his home. Nonetheless, he is a life-long pacifist who managed to fulfil his compulsory military service obligations in the 1960s by working with developmentally disabled children—despite the official absence of provisions for either male conscientious objection or alternative service in Israel. “I am active because wrong things have been done,” Gvirtz told me, “not because I believe I will change something. There is wrong that has been done, so I’ll fight it. I’m not sure that I will succeed.”

The way I understand this conflict is that one society came into the living space of another society. This is the essence of the conflict, to my understanding. Therefore my work is directed mainly to face these issues: land confiscation, house demolition, deportations—all of these kinds of activities that Israel is doing—and to the understanding that if this process is not stopped, there is no chance for peace. In recent years, I have become very active [on the issue of ] Bedouin inside Israel, because the process of pushing the Palestinians away from their territory was not only in the occupied territories, it was very active and very intensive inside Israel, and specifically now against the Bedouin.

Gvirtz is involved in a number of activist groups, including the Israeli Committee Against House Demolitions (ICAHD), and views house demolition as a singularly traumatic and damaging aspect of the occupation. From talking with Palestinians, “I can begin to imagine how traumatic it is,” he said. “And Israel is building its enemies for generations by these activities.”

But I don’t believe I’ve reached the real deep meaning of it for people, not only to those it happened to, but to neighbours who have seen it. How traumatic it is for children it happened to and for neighbour children who have seen it and are afraid it will happen to them. It is a very traumatic event, and different people react differently to it. But for sure, some percentage of them will retaliate violently. Most of us understand house demolition only rationally, but rational understanding is far, far away from reaching the real meaning of it.

“What is much, much, much less visual and maybe less traumatic, but more essential, is land confiscation,” said Gvirtz.

This is, together with house demolition, the essence of the conflict. You take the territory out from under the feet of the Palestinians; this is the essential issue. The Oslo process,3 instead of stopping the process of pushing the Palestinians away from their territory, was speeding it up by increasing dramatically the number of settlements—which meant there was massive land confiscation and massive house demolitions, and even deportations. This is why we started the Israeli Committee against House Demolitions.

The real issue in the conflict is not security, as is often claimed, says Gvirtz. “The real issue in our conflict is the land; it is the land and it is the effort to get maximum land with minimum population—continuing the situation as it is, hoping that more and more Palestinians will leave the territories.”

We came into Palestinian territory when there was a foreign ruler that allowed us to do it, and then later we threw out most of the Palestinians from their homes and their land—they became refugees—so we built Israel on the ruins of the Palestinians. Now we are occupying the rest of their territory with a very oppressive and cruel regime. And yet, for most northern and western people, the Palestinians are the terrorists and we are defending ourselves. Why? The situation is exactly the opposite.

Converts to NonviolenceMustafa Shawkat Samha Several of those I interviewed—particularly amongst the Palestinians—described what might be regarded as something of a “conversion experience” in arriving at their commitment to nonviolence. One of these was Mustafa Shawkat Samha, a twenty-something village activist I met at the Celebrating Nonviolent Resistance conference (held in Bethlehem, December 27–30, 2005). Before his arrest in 2002, said he, “I didn’t believe exactly in nonviolence.”

But when they arrested me and some soldiers started to beat me, because I’m handicapped and I cannot protect myself,4 I discovered that the power of muscles, the power of weapons, is not the only power. We have the power of the mind. We have the power of speech. We have the power of negotiation. We have the most important power, the power of [our] humanity. And I’m sure that those soldiers, who beat me hard, are not happy about their actions toward me, but they’re used to doing this. It’s the short way to get what they want, to punish. But even while they were beating me, I was talking with them. Like: “Are you really happy with what you are doing? Think about yourself. Think about your humanity.”

We, Palestinians and Israelis, are as if we are in a boat in the middle of the sea. So we have the responsibility to protect this boat, to reach the beach. And we cannot reach this beach by hating each other, by killing each other. We can reach this beach if we feel deeply our humanity, if we believe that we have to live together and we both have the same right to be alive.

Samha spoke of nonviolence as being a way that is stronger than violence and one that can “create a new meaning of life for you,” whereby you share in the struggle, neither being violent nor passively “standing aside and just watching,” a way that encourages “a loud voice from Israel” that proclaims: “Stop killing. We want our rights and they want their rights. Stop killing the others. All of us are human. All of us can live together. Nobody is a slave for the other, and nobody has the right to kill others.” “Because of all these things,” says Samha, “I believe in the nonviolence way and I’m working in this way. And if they will they arrest me a million times, I will continue struggling in this way, and I will not change what is in my heart. I cannot hate anybody, even for what they are doing to me.”

Sabrin Aimour Sabrin Aimour is a Bethlehem University student who wears the hijab (head covering worn by religious Muslim women), but with a Fatah keffiyeh around her neck to show her affiliation in the upcoming student elections. She is a former supporter of Hamas and believed in armed struggle before attending a workshop led by local nonviolence trainer Husam Jubran. She had hoped to learn “something new” during the training, but came away convinced and empowered by the nonviolent approach and is actively recruiting her friends to enrol in future training sessions.

I was searching for alternatives, but at the same time I believed that violence works in many cases. I came to the training to learn something different, something new. I learned to deal with problems in a different way, to address them in a deeper way, not just to address the surface, but to deeper in understanding the conflict and addressing it. I learned and now I understand that nonviolence is much better than violence and I could help and support people through nonviolence and that to solve problems using nonviolence makes it more efficient and gives me a feeling of security. And it helps me become more powerful in expressing my opinion and not to be afraid, for example, of showing the keffiyeh in front of soldiers.

Lucy Lucy [surname withheld by request] is another young Bethlehem-area woman who is a relative newcomer to nonviolence. I interviewed her at the Wi’am Palestinian Conflict Resolution Center in Bethlehem, where she is now a youth leader:

I was raised in Bethlehem, and the First Intifada was when I was a teenager. It was a very hard time, and I did not believe in what they called nonviolence. It was a strange idea; I thought it was like a new technique we adopted from the West. During the ’67 war, my grandmother’s house was shelled and my grandfather, my aunt, and my uncle had been killed, so I grew up with revenge on my mind.

Lucy described the evolution of her thinking, commenting, “Day by day, I tried to change my mind.” As a young person in the 1990s, she sought out organizations that dealt with the conflict in ways that went beyond dialogue (an approach she regarded as ineffectual). She did some support work for the Jahalin Bedouin side-by-side with Israeli activists like Rabbi Jeremy Milgrom, and also worked at the Alternative Information Center (AIC) office in Bethlehem (now relocated to the neighbouring town of Beit Sahour). Her interest in the concept of conflict resolution then led her to the Wi’am Center, where, however, she initially avoided participating in its Palestinian-Israeli cross-cultural activities. “I was against these projects,” she told me. “I thought they would not achieve anything, dialogue is not important during this time, what is important is to resist and to get our freedom, to get rid of occupation.” It was the increasing militarization of the Second Intifada that ultimately caused Lucy to rethink her position regarding nonviolence.

I started my life not believing in nonviolent resistance, so how could I change my mind from believing in using arms to achieve what we want to nonviolence to achieve what we want? In the First Intifada, for me, [actions] like throwing stones and carrying the branch of olive trees were symbols of nonviolent resistance. But the Second Intifada is completely different. At a certain point I decided, “No, I have to stop. This is not going to change.” Arms lead just to bloodshed and revenge, no more than this. I felt that using arms is not going to achieve anything—just to see more blood, more victims. This was the most important part for me. That’s why I promised myself to be an active person in the field of peacemaking: to work hard on that, to educate people to raise their awareness of the effect of nonviolence, especially the methods they use, the skills, and that’s what we are doing [at the Wi’am Center].

Nayef Hashlamoun Several former supporters of armed struggle—including fighters—described circumstances or specific events that brought them to nonviolence. Nayef Hashlamoun, founder of the al-Watan Center for Civic Education, Conflict Resolution and Nonviolence in Hebron, for example, tells of being involved in military action in South Lebanon. He recalls that the officer in charge of training told him, “Listen, you have to understand what our religion is telling us. You have to know that you haven’t the right to kill any people without reason, to kill a tree or to ‘kill’ even a stone for no reason.” After reflecting on this statement, said Hashlamoun, he was unable to sleep that night. “In the morning I took the decision that I have to change my way from the violent way to nonviolence. I left Lebanon to [study journalism in] Jordan. I said I have to fight, but without guns.”

Ali Jedda Ali Jedda worked at the AIC for five years. The son of a Muslim from Chad who had come to Jerusalem on pilgrimage in the early 1900s, Ali grew up in the African Quarter (part of the Muslim Quarter) of the Old City and was a student at the College des Frères when the Israeli occupation began in 1967. “I was looking forward to become a lawyer, to become a doctor, something like that,” he told me.5 But the occupation and consequent financial difficulties had dashed these dreams. Thinking back to those days, he recalled, on top of the disappointment of having to leave school, “first of all, the way the Israeli soldiers behaved to us— stopping us in the streets, harassing us, and sometimes kicking us” and “the way Israeli civilians used to behave when they’d come to the Old City. They used to come in groups to the streets of the Old City, dancing, singing, in a very arrogant way.” “I think I lost my dignity,” he said, “my personal and my national dignity.” He got involved in militant politics and joined the PFLP—Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine. “And at that time,” he told me, “the circle of violence was so wide. I placed [a] bomb at Jaffa Street. Because of that bomb nine Israelis were injured.” The attack was meant as a reprisal, he explained, for an Israeli bombing raid on a Jordanian city the day before, which had killed many civilians. “Our main intention at that time was to send a message to the Israeli civilians saying to them, “Look, if you don’t protest, if you don’t act or react against the brutality of your government, unfortunately at the end of the day, you are going to pay the price. A month later, I was arrested.” Jedda spent the next thirteen years in prison, during which time he had a change of heart.

I came to a definite conclusion that my main allies in my fight, in my struggle against the occupation should be the Israelis themselves: the sector of the Israeli society who are totally against the occupation and who are looking forward for a secular democratic state—which is my main idealistic solution—in which both of us can live together in real peace and equality.

Upon his release, Jedda “began working with such people”—at the jointly run Alternative Information Center. A year or two into the First Intifada, he felt “obliged to move once again to the Palestinian side, to be very close to what [was] happening on the Palestinian side.”

I was curious as to what brought about Jedda’s change of heart. “It’s my elementary right as a human being to fight against the occupation,” he reminded me, “but today, I say simply I’m not ready to do what I have done in 1968, for two main reasons.”

I have today five children, three girls and two boys. If I can’t stand that somebody is going to harm my children, I’m not ready to harm children of others. On the political level, my Israeli friends are Israelis who are really serious about peace, and they want to live in peace with the Palestinians. So, if I place a bomb, the bomb can’t make a difference between the good Israelis and those monsters—I mean the settlers. So for that [reason], I’m not ready to do it. On the contrary, I’m doing my best now to build a bridge to reach to more and more sectors of the Israeli society and to convince them that the best solution is that we have to fight together in order to achieve that state—the secular democratic state.

Though he doesn’t expect to live to see his vision achieved, Jedda hopes that “maybe my sons or grandsons will see it.”

I say today simply, I am a candle which is burning itself to give light for others: for my children and for the Israeli children, also. Because both generations—meaning my children and the Israeli children—are [undergoing] a process of psychological destruction, and we have mainly to blame this Israeli occupation. And this is what I think. Whenever they ask me, “how do you look [at] what you have done in 1968,” I say to them: “I was a victim. The Israelis who were injured were victims. Both of us are victims of the occupation.”

Ghassan Andoni Ghassan Andoni, a cofounder of both the Palestinian Center for Rapprochement (PCR) and the International Solidarity Movement (ISM), recalled “I started my life as a committed nationalist who believed strongly in fighting to liberate Palestinians and return them their rights.” First jailed by the Israelis in 1972 while still in high school, Andoni was active in the resistance to the occupation until moving to Baghdad to attend university in 1976. While there, said Andoni, “I was really moved by the scenes of attacks against refugee camps by the Phalangists and the Syrians during the civil war in Lebanon.” He continued, “I decided to volunteer and go to Lebanon—to do work that was similar to what ISM volunteers do right now in Palestine.”

I spent three months in Lebanon, and there I had the shock that made me feel that nonviolent resistance or civil-based resistance is the way to fight against oppression and violence. Part of that was that I felt that people who hold guns become captured by the guns, and instead of [them] leading, the guns started leading [them]. I asked so many people the question, “Why are you fighting here?” and I realized that people were fighting because they get used to fighting, and because there is an enemy and then, in order to survive, you need to fight. My concept of fighting was not to survive, but to make things better, more human. Even in Lebanon at that time, I realized that the fighting was pointless. But nobody was questioning it.

“Therefore,” he said, “I realized that the gun is leading, not the people, and that made me decide to come back and live in my little town inside the occupied territories, rather than spending the rest of my life in [the] diaspora with the Palestinian liberation organizations or movements.” After further study, in Palestine and the UK, Andoni returned in 1984 to teach physics at Birzeit University. With the outbreak of the 1987 Intifada came what he referred to as “the other turning point in my life.”

At that point I realized that civil-based resistance is not only a concept, is not only an idea that is suitable to India, South Africa, the Civil Rights Movement in the States; but I could see the potential in the Palestinian massive resistance—mainly nonviolent—that started in December 1987 and managed, literally in the first few months, to turn the mighty Israeli force to useless. That’s why I decided to engage fully in that Intifada. When I cofounded the Rapprochement group and started working to prepare the society in my town for civil disobedience and started opening channels of communication with Israelis and internationals, we managed actually to contribute to a movement in this little town that attracted the attention of so many people. We managed to build up lots of good models: the tax resistance, throwing back [Israeli] identity cards, boycotting Israeli products, starting underground schools when schools were closed, victory gardens. We started community work that managed to replace the institutions of the occupation. And finally the occupation felt really threatened by a resistance that did not harm or hurt or kill any of its soldiers, but rather forced them to lose control. And that was very frightening to them, and that’s why they attacked this little town, Beit Sahour, severely, hoping to crack down on this experience, fearing that this might spread out to other regions and then there would be a total collapse of control.6

Andoni’s work with PCR and, more recently, with ISM as well, has involved providing leadership and training in nonviolent resistance techniques, since both organizations are committed to this approach.

Promoting Nonviolence through Training and EducationHusam Jubran