8,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Emma Gee

- Kategorie: Fachliteratur

- Sprache: Englisch

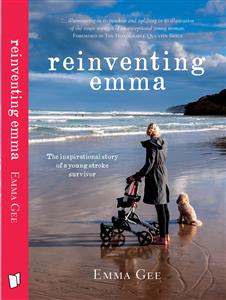

At the age of twenty-four, Emma Gee’s future stretched before her invitingly. But just weeks after climbing Borneo’s Mt Kinabalu, this occupational therapist and avid runner, develops disturbing symptoms. Her story moves from mystery to tragedy when, during difficult brain surgery, she suffers a debilitating stroke and is left in a coma. When she wakes she is unable to move, speak or swallow, and is suddenly dependent on the medical system she had worked within. Emma must come to terms with learning to walk and talk again, and adapting to a completely new life. Reinventing Emma tracks Emma’s experiences as she reinvents herself. Weaving excerpts from her diary, observations and memories, her story is a powerful testament to how, with love, support and a positive mindset, a life can still be incredible.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Ähnliche

“It’s not what happens to you that matters, it’s how you choose to deal with it”

Emma Gee

In loving memory of my grandparents, Joy and Charles Robinson – you provided me with a solid foundation and demonstrated how to live according to your values.

To my parents, Lyn and David Gee for your unwavering love and devotion. By your example, you instilled in me such a positive, compassionate and accepting approach to life. The opportunities you provided enabled me to find meaning in my life and pursue my passions. I will be forever grateful to you and the incredible sacrifices you both have made.

This book is also dedicated to all of the people who encounter seemingly insurmountable challenges in life.

Published in 2016 in Australia by Emma Gee

www.emma-gee.com

Text copyright © Emma Gee 2016

Book Production:OpenBook CreativeCover Design:Anne-Marie ReevesCover Photograph:David GeeConsulting editor:Annie HastwellCopyedited by:Ann BolchEmma Gee asserts her noral right to be identified as the author of this book.

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication nay be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior written consent of the publisher. The only exception is by a reviewer, who may quote short excerpts in a review.

Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry

Author:Gee Emma, author.Title:Reinventing EmmaISBN:9781925144291 (paperback)9781925144307 (ePub)9781925144314 (.mobi)Subjects: Subjects: Gee, Emma E.

Cerebrovascular disease—Patients—Australia—Biography.

Occupational therapists—Australia—Biography.

Motivational speakers—Australia—Biography.

Dewey Number: 362.196810092

Although the author and publisher have made every effort to ensure that the information in this book was correct at press time, the author and publisher do not assume and hereby disclaim any liability to any party for any loss, damage, or disruption caused by errors or omissions, whether such errors or omissions result from negligence, accident, or any other cause.

This book is autobiographical, and is not intended as a means of disseminating medical advice. Content contained in or accessed through the book should not be relied upon for medical purposes in any way. The advice of a medical practitioner should always be obtained.

In order to maintain their anonymity some names of individuals and places have been changed.

contents

Introduction1Beginnings2A Taste of the Future3Signs of Something Wrong4The Mystery Deepens5The Alfred – Digging for Reason6A Diagnosis at Last7More to Prove8The Therapist Becomes the Patient9A Brief Taste of Independence10A Date for the Big Day11So This is Goodbye12The Quiet Before the Storm13Things Don’t Go According to Plan14From Dreams to Reality15Waking Up16Reality Bites17Deficits Revealed18At the Mercy of Staff19Passing on the Worry Baton20Handballed to Talbot21Therapy Begins22Three Months on – the Rehab Roller-coaster23Mid-therapy – Baby Steps24Leaving Talbot25A Dependent, Disabled Baby Returns Home26The New Me Steps Out into the World27Taking My Disability on Holiday28Dependent Independence!29On the Shelf30The Daily Churn of Rehab31Searching for Purpose32Moulding a New Identity and Direction33A New Love Life34A Real Working Girl Again35Independence Tested36Out There and Advocating37The Longevity of Stroke38Life Now39Finding Where I FitForeword

What a marvellous thing Emma Gee has done for us in writing her searingly honest account of her extraordinary journey across a decade as she has struggled with courage, hope and determination to recover from a haemorrhagic stroke, to reinvent herself, to keep going day after day through the toughest gullies.

Yes, her story has moments of wry humour, deeply affecting insights, glimpses of joy but again and again, Kipling’s words about “forcing heart and nerve and sinew” come to mind.

Emma’s compelling memoir opens with an almost lyrical account of a charmed childhood, halcyon days at university, overseas travel, confidence growing on the threshold of personal and professional achievements, adventures in spades.

Completely and utterly out of the blue it all began to change. Her very life was threatened. Every aspect thrown into chaos as frightening, confusing, horrific anxiety struck her down. Her body began to deteriorate. The search for a diagnosis and treatment led to brain surgery. Emma suffered a devastating stroke. Her own remembrances and her mother’s diary notes of these harrowing experiences are confronting. They bring awareness and understandings that are powerful and instructive, so many painful truths.

We travel beside Emma on her gruelling recovery road. Oh, the tension in her storytelling. Every day was a struggle, “my wings had been clipped. I may no longer fly”. Every day terror surrounded and engulfed her.

As an occupational therapist, Emma has insightful and constructive observations to make about the rehabilitation rollercoaster.

This book is confronting, illuminating in its candour and uplifting in its illustration of the inner strength of an exceptional young woman. Love shines through the pages; love and family, her identical twin sister, siblings, partners, little children, enduring friendships. Those through thick and thin devoted parents who gave unstintingly to Emma’s future, encouraging her independence.

The wise mother treading on eggshells worrying about being pitying or patronising, who was both in the best way. The father who sat in the wheelchair to make it look normal. How inspiring are these anecdotes of the day to day loving, caring, sharing, grief, loss and joy!

Reinventing Emma must be read by all health professionals and by all of us who want to strengthen our knowledge of our shared humanity.

I am inspired by Emma’s forthright advocacy, her description of her gutful of society’s misconceptions about disability. I am inspired too by the recovery that came with work and purpose, her public speaking, her mentoring, support and encouragement for stroke survivors.

We must learn from this remarkable book how to offer help, especially to people with disabilities, to be aware of the emotional and financial toll disability imposes and to hold fast to the principles of the human rights doctrine about the dignity and worth of every human being.

Emma, we are indebted to you.

The Honourable Quentin Bryce AD CVO

An inspiring and insightful read. An amazing true story of courage, compassion, and commitment in the face of devastating loss. Emma Gee’s story will move you deeply and her resilience will astound you.

Dr Russ Harris, M.B.B.S.Author of The Happiness Trap

This book is a significant contribution to the ‘therapist as patient’ literature. At once ferociously intelligent and deeply felt, it is required reading for every health professional, every health consumer.

Nick Rushworth,Executive OfficerBrain Injury Australia

Reinventing Emma is a moving tribute to the courage of one inspirational young lady who, although representative of many thousands of young people who suffer a stroke, is exceptional because she chose to find meaning and purpose from her condition. Her account of the sudden change of life as it once was, along with the partial loss of the very essence of herself, I found compelling. It was evident Emma found herself with two choices – she could spend her life mourning the fact that her dreams were now shattered, or do whatever she could to change what could be changed, without forsaking the insight to accept what couldn’t. So Emma learnt to push the boundaries of her impairments, and in so doing, she teaches those around her to do the same. Despite living in a society which values status and ability, the way in which Emma reinvents her life, teaches us that individuals should be accepted for who they are and whatever contribution they can make to society. This resilient young lady has reaffirmed my own belief that human development cannot be accurately determined by science, nor can potential be predicted, or spirit measured.

Cheryl Koenig OAM. Author & Motivational Speaker

Like Emma, I am an occupational therapist, and I have worked with many stroke survivors. Reinventing Emma taught me many additional things about stroke, including strategies that other stroke survivors [and therapists] can use to improve their quality of life. Emma’s book is beautifully written and a pleasure to read with great real-life stories interwoven throughout and will leave you wanting more

Dr Annie McCluskey,Senior Lecturer in Occupational Therapy,The University of Sydney

Introduction

I’ve been on a challenging yet amazing journey over the past ten years. My life has been turned upside down in ways I could never have imagined. In 2005, at the age of 24, I survived a haemorrhagic stroke and went from being a young, sport-loving, professional woman and full-time therapist, to being a helpless, dependent nonentity. Overnight I became a powerless patient, like the ones I had been caring for. The roller-coaster ride that began with a sore knee has led me on a totally unexpected and unimaginably difficult journey. And yet everything, both good and bad, has shown me, surprisingly, what is possible when you accept life’s challenges.

The sudden transition from therapist to patient has given me a completely different perspective. When I first reached the point in rehabilitation where I could read and write again, I had a passion to share my insights about life as a patient. I decided that this book would be for other health professionals. With that in mind I started a Masters degree but quickly realised another qualification was not going to help me to impact people as directly as I wanted to. I felt as though I needed to make a difference right now.

I’ve walked in the shoes of a patient and I want to tell that story. I’ve realised how much health professionals really don’t know about what it’s like to be a patient, and how even the little things they do without noticing can affect someone else’s path to recovery. I now know so much more about improving the quality of life for patients and their supporters. And the bigger lesson I’ve learnt, and want to share with everyone, is the importance of resilience when life doesn’t go to plan.

It’s taken me quite a few years to write this book. Always a keen diarist, I faithfully recorded every amazing and terrible thing happening to my body, from the first mysterious symptoms through to waking up after being in a coma. My writings range from serious attempts at storytelling to scraps, strings of words that were all I could manage at times to describe the nightmare world I had found myself in.

I’ve heard plenty of inspirational stories, read books and seen movies about people who have survived in the face of great personal odds. Those stories helped me but they also intimidated me a little when it came to writing about my own experience. I don’t feel as though I’ve accomplished an amazing feat and, even though I work as an inspirational speaker, I find the title doesn’t sit comfortably. My journey seems more mundane. I’ve survived and I go on surviving day to day. That is what I want to share. This book is not all about success, but an authentic account of overcoming the difficulties I’ve encountered and still do encounter every day in my stroke recovery.

This is only my experience. Despite undergoing a life-changing event at a young age and learning to live with disability, I could never presume to fully understand how a brain injury may have affected others. A stroke, whenever it happens, is a terrible and life-changing experience. Everybody’s story is different and, although we share many struggles with tiredness, and lack of understanding, support and motivation, disability comes in many forms. It can happen at varying life stages and impacts us and those we love in many different ways. I hope my story can help not just those who have gone through their own personal nightmare, but also give some insight and extra understanding to those who love and care for them.

Lying in intensive care I never imagined I would have balance in my life again. In fact, I am dumbfounded that I have been able to reinvent myself and pursue what I love. I have developed amazing relationships, returned to meaningful work, begun my own business and written a book, all while continuing to juggle my seemingly never-ending rehab. But I have learnt that it’s not what happens to you that matters, it’s how you choose to deal with it.

Chapter 1

Beginnings

“Open your eyes Em!” a voice instructs.

I’m too tired to know what they’re asking me to do. I am lying on my right side. All I can taste is blood. All I can feel is cold. All I can hear is my twin sister’s nervous chatter and my older sister quietly sobbing. I’d prefer to sleep.

I do.

Again a voice pleads, “Darling, please open your eyes.” Now someone’s holding my hand, their thumb delicately moving from side to side. It’s a familiar voice and a familiar touch. I tell myself to open my eyes. I try but it doesn’t work. I’ll speak to them later. Right now I need to sleep.

“You’re OK, the operation went well,” someone is saying, too loudly. I fight my way out of strange nightmarish dreams. I’m cold, tired and I don’t like this place so I instruct my body to curl up in a ball and drift back to sleep. But my body won’t budge. Perplexed, I try to concentrate harder on moving any body part, even wriggling my little finger would be OK. But again my entire body stubbornly remains still and limp. I’m trapped in a bubble inflated by sickly smells of blood and disinfectant. I try to cry out for help but no words come. Nothing works. My body is broken. I can’t move or speak. This wasn’t what I planned when I made the decision to have this operation.

For the 24 years leading up to this, life had been sweet. I entered the world on the 28th of July 1980, seven minutes before my twin sister Bec. I had those minutes alone with my doting parents until the doctor declared, “Bloody hell, there’s another one in there!”

Mum gasped, “Another what?”

My shocked Dad murmured, incredulous, “Lyn, we’re having twins!”

Lyn Gee cradling her newborn baby girl twins on the 28/7/1980.

Unnamed, we were known as ‘Twin 1’ and ‘Twin 2’ for three days, and were left in hospital while Mum and Dad bought another one of everything and prepared my two older siblings for the arrival of their twin baby sisters.

Growing up as an identical twin had its good and bad points. I always had someone to play with. From Grade One we were deliberately separated to help us form our own identities. We both had bobbed blonde hair, identical gappy teeth and answered to each other’s names. Even our older sister and brother often failed to see us as two separate little individuals. In fact, Mum tells the story about my three-year-old brother Pete lying on the carpet and playing roughly with us when we were just four months old. Mum cautioned him. “Darling, please don’t be so rough with the girls, they’re only little.” Despite her warning he continued to tumble, poke and prod.

“Peter, what did Mum say?” she pleaded, walking over to scoop us up, balancing our fragile bodies on her hips.

Pete grinned and reassured her. “Don’t worry Mum, if one cracks open we’ve always got the other one!”

Em and Bec’s first day of school, Melbourne 1986.

Little did anyone realise that 24 years later one would ‘crack open’ and what challenges that would present.

We looked the same, but we could act differently. Bec was strong, stubborn and unstoppable whereas I was the sensitive one. I longed for her strength of character. Bec was always more daring than me in tackling the unknown. She’d jump off diving boards and climb high trees while I hung back.

“Face your fears,” she would say to me. One day I would become master of this, but what my sister didn’t say was that facing your fears doesn’t necessarily make them go away.

One way of overcoming fear is to remember the nice things. My childhood was a huge portion of my disability-free life and so it’s a favourite thing for me to remember. A time when I ran from place to place and was just another ‘normal’ kid. A time when I went around and around the skating rink for fun, when a grazed knee was healed immediately with a kiss better or a Band-Aid.

I remember our neighbourhood as an exciting little world of its own – a kingdom where we kids reigned free and independent. My very favourite people in the street were the Mullins family. They weren’t quite next door. There was a house between us but we ignored that and spent most of our time dreaming up ways to connect our houses – flying foxes and underground tunnels. I spent a lot of my childhood playing with the Mullins girls. We had sleepovers, built cubby houses, spent hours playing board games and went on bike rides.

But the biggest influence in my life was my family. There were six of us, my parents and four kids – my older sister Kate, my brother Pete, my twin sister Bec and me. Although we had normal sibling quarrels, we grew up in a loving and nurturing place and came to love and respect each person’s individuality. My parents were great role models, their contrary personalities along with their aligned life values balanced perfectly. Mum’s a sensitive down-to-earth person, always there for you and very open. Dad is very private, pragmatic and able to distance himself from a situation. At the same time he is very loyal. Their Christian faith was always at the centre of their lives and mirrored in all that they did. They provided us with a secure, accepting environment, at the same time challenging us with new opportunities and adventures. Our parents captured the potential in all four of us and we felt valued and believed in. They ensured we were grounded, exposing us to those less fortunate and in their regular acts of generosity and community involvement they instilled in us a strong sense of personal values. These were never forced upon us. Rather they seemed to subconsciously plant seeds in us, weaving them through the way they went about their lives. As Bec and I were identical twins, they always tried to make each of us feel unique and seemed to effortlessly distribute their overflowing love to all of us kids evenly.

Em clicking her heels, Anglesea 2002

The importance of family was paramount in my mum’s childhood, so we spent many holidays with our extended family on my grandparents’ farm, ‘Springview’, in Young, New South Wales. Here there were 1000 acres to explore and have adventures with my cousins.

My grandpa would welcome us with a tight squeeze, clenching his false teeth in preparation and effortlessly lifting our four dangling bodies in unison. Then my aproned grandma would appear and our bellies would soon be full, after consuming her amazing spread of home-cooked food.

On the farm we were invincible and free. I longed to be tough like my country cousins. Each stay I would try my best to push aside any urges of complaining about teeny scratches or fearing getting dirty. We milked cows, fed the foul-smelling pigs, made cubbies in the pine trees and lit bonfires. As city kids we loved doing non-city things like riding motorbikes and running barefoot on dirt tracks. While recalling these times reminds me of all of the things I am no longer able to do, at the same time each memory is precious and makes me appreciate the wonderfully wild and active childhood I was lucky enough to have. In some way each farm trip reset my perspective on life and left me feeling rejuvenated and revived.

Uncle Tim, Kate, Pete, Em, Bec & Tom at Springview, NSW 1988.

Holidays over, I was excited to resume my busy city lifestyle where I took up as many activities as I could manage. From early primary school I learnt classical ballet and loved the discipline, creativity and grace involved in performance. I also fell in love with long-distance running and netball. Throughout high school I became involved in everything. Whether it was drama, dance, music or sport, I tried it. In most school drama productions I was guaranteed a role as a twin. Bec and I played Tweedledee and Tweedledum. In another play we were cast as twin grandmas, delivering our lines in unison. If the script didn’t have twin characters, they were added.

In reality, though, by high school Bec and I were starting to form more separate identities, and I was getting a feeling for who I really was. I enjoyed being with people and caring for them. As a lot of my family were in the health professions, and two of my aunties and my older sister were occupational therapists, I started to think about a career in the health sciences.

During those last years at school there were shadows on the horizon. In 1997 my mum was diagnosed with Type 1 Diabetes and later with a cavernous hemangioma (a type of brain tumour that had destroyed her optic nerve, causing her to lose the sight in her right eye). Then my twin sister was hospitalised with a stomach condition and had to have sudden life-threatening surgery. It was my first realisation that life didn’t always go according to plan. They both recovered and even though Mum had vision loss and Bec couldn’t sit her exams that year, it didn’t really affect my life hugely. I was House Captain, and finished Year 12 with a score of 93.5. I felt invincible. Nothing was going to get in my way. Career, marriage, children, it all lay ahead. So I thought…

Chapter 2

A Taste of the Future

In 2003, three years into my occupational therapy degree, I decided to take myself off to Tanzania for a few months. Looking back, I can’t believe I did this. I’d led a sheltered life and hadn’t even done the Europe trip like most of my friends. Mum was very hesitant to let me go and insisted I wear a wedding ring to ward off any admirers. It didn’t work. I had 18 marriage proposals in three months! I volunteered as an assistant at the Tuppendane Centre in Maji Ya Chai village, Arusha, where my job was to help care for and educate 70 street children.

Em takes a break from her studies, caring for 70 street children in Arusha, Tanzania 2003.

Tanzania certainly provided the challenge I was looking for. There was no electricity or water, and my accommodation was a rat-infested concrete blockhouse. The guard of the centre would lock me in at night to keep me safe, but inside was worse than out. I was trapped inside with the furry creatures, and plugging the gaps in the walls with my camping socks didn’t deter them. All night rats would squeal and run around the room and clamber up and down my mosquito net as I pelted them with boxes of medication, the only weapons I had. It was a hideously claustrophobic experience that I was to relive in a surreal way years later when I woke up in hospital trapped inside my own body.

Being the only mzungu (white person) in the small village, I stood out, something I’m used to now but wasn’t then. On my daily walks I was joined by a stream of African children, my blonde hair was patted for good luck and everyone would say, “Good morning to you!” It was the only English phrase they knew and they used it whether it was morning, afternoon or night.

Living in a third world culture was a huge eye-opener. ‘Sick days’ didn’t exist, even though many villagers were constantly suffering from malaria. Complaining, I soon realised, was just not part of their culture. One day I had lunch at a villager’s house and was saddened to see his two-year-old son with a severe eye infection. He was too young to complain but even if he was able to I’m sure he would not have mentioned his discomfort. His family couldn’t afford medication, and the only way I could help was to buy him eye drops. Now, when I constantly suffer eye infections, I can’t imagine letting them go untreated.

Seeing the lives of the children in Africa was like being on another planet. I couldn’t believe how sheltered my life had been. Typically I’d pass children on my walk through the village carrying buckets of water on their heads. Four-year-olds would be put in charge of ten cattle and a donkey, with only a stick to control them. Children seemed almost expendable; mothers would plead with me to exchange their newborns for a few dollars so they could buy a bag of rice.

A disabled child was a source of shame. Once I saw an African lady carrying ‘dizzies’ (bananas) on her head, and carrying a newborn baby on her back covered by a sarong. It was hot and I thought she was protecting him from the heat. Then a local villager approached her and they exchanged words about the new baby. The mother lifted the shield, I assumed to show off her new baby, but both mother and onlooker pointed and laughed at the baby, who had Down Syndrome. He was clearly regarded as a reject.

Another cultural learning curve was when I witnessed one of the 70 orphans in my care, an eight-year-old girl, being sexually abused by a nine-year-old boy. When I told the visiting social worker about it, assuming he’d be shocked and take some kind of action, he just said, “Emma, they are street children, and Amelia is retarded!”

I was outraged at his words. “Well surely that is even more reason to act now!” He didn’t seem fazed by my anger and went on crunching on his maize. I couldn’t believe he could swallow it.

At the Tuppendane Centre I was quickly thrown in the deep end. A few days after I arrived the head of the centre disappeared with the large sum of money I’d paid to the volunteer organisation. Then the sole nurse left to give birth, leaving me in charge of the health and education of all of the children. Overnight I became nurse, teacher and mother to a wild bunch of non-English-speaking orphans, ranging from toddlers to young adults. With the extra challenge of no water or electricity, my twin sister’s motto of ‘face your fears’ was truly put to the test.

As bad as things were, I was surrounded by uncomplaining Africans, so I really had to rise to the occasion. Before I could get anything done I needed to be able to communicate with the children, so I set about learning some basic Swahili. They had no shoes, so I bought a hundred pairs of malopas, the African version of thongs. I also purchased rat-proof barrels in which to keep food, and contacted a toothbrush company in England and asked them to sponsor the centre by sending toothbrushes. Most of the kids had fungal infections on their scalps, so I also launched a haircutting and treatment program.

Living within a very vulnerable community was a huge personal challenge. My experience there unmasked qualities that I didn’t know I had. Away from my ‘twinness’, my dormant stronger attributes, qualities that I had thought only Bec had, revealed themselves. Travelling alone, I was forced to be more direct, strong-minded and assertive. I also saw firsthand the importance of many human skills like communication that I’d taken for granted. When living in Africa I had to rely heavily on facial expressions and body language to work out what was going on around me. In a strange way it was a foretaste of what was to come. Not being able to speak the language made me feel isolated and helpless, like I would later feel when I lost the power of speech.

In Africa I really saw and understood what discrimination means, something I now experience daily because of my disability. The frustratingly slow-paced culture taught me patience, which I’ve certainly needed through my long months and years of rehabilitation. It was also a real-life lesson in taking the time to understand where the other person was coming from, rather than just acting like the ‘expert’. Later, when I became a patient myself, I learnt to value therapists and others who used this empathetic approach.

I only spent three months in Africa but they were intense. What had been seemingly important in the western world became irrelevant. I learnt that when faced with any obstacle and out of your comfort zone, you can still have control over how you choose to deal with things. Their ‘live one minute at a time’ approach made me see how much I had been focused on acquiring certain possessions, achievements and status before I could be content. The African people had little but it didn’t seem to affect their happiness in the present moment.