11,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Forum

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

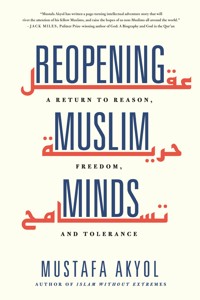

A fascinating journey into Islam's diverse history of ideas, making an argument for an 'Islamic Enlightenment' today. In Reopening Muslim Minds, Turkish scholar and author Mustafa Akyol frankly diagnoses 'the crisis of Islam' in the modern world and offers an authentic way forward. Diving deep into Islamic theology and sharing lessons from his own life story, he reveals how Muslims lost the universalism that made them a great civilization in their earlier centuries – and what the cost has been. He highlights how values often associated with Western Enlightenment – freedom, reason, tolerance, and an appreciation of science – had Islamic counterparts, which were tragically cast aside in favour of more dogmatic views. By rereading the Qur'an and revisiting the Sharia, Akyol shows the path to a renewal in Islam.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 491

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

Additional Praise for Reopening Muslim Minds

“Much more than an impassioned defense of tolerance and reason, Mustafa Akyol takes his readers on a truly enjoyable and enlightening journey through Islamic theology and law. With brilliant wit and eloquence, Akyol has written a book of undeniable presence and power.”

—Dr. Khaled Abou El Fadl, Distinguished Professor of Law at the UCLA School of Law

“This is an alluring book; it is an inviting book; it is a remarkably erudite book. . . . Akyol writes with intuitive intelligence, empathy, and—dare I say it—love and hope.”

—Asma Barlas, professor emerita in the department of politics at Ithaca College

“An accessible, stimulating, and thought-provoking work in which Akyol sparks lively conversation.”

—Ebrahim Moosa, professor of Islamic thought and Muslim societies at the University of Notre Dame

“A timely and passionate reminder that universal values like tolerance, freedom, and equality . . . may be extracted from Islam’s foundational texts.”

—Asma Afsaruddin, professor of Middle Eastern languages and cultures at Indiana University Bloomington

“For Mustafa Akyol, the Islamic heritage is not to be approached as a sterile museum but a lively garden which can always and at any time be cultivated anew.”

—Enes Karić, professor of Qur’anic studies at the Faculty of Islamic Studies at the University of Sarajevo

“A well-reasoned, broad reminder of what Islam and its culture have represented over the past fourteen centuries . . . to live together rationally, freely, and accepting of one another.”

—Charles E. Butterworth, professor emeritus in the department of government and politics at the University of Maryland

“Reopening Muslim Minds is brilliant, wonderfully written, and full of big ideas. I also disagree with the main argument, but it challenged and pushed me throughout.”

—Shadi Hamid, senior fellow at the Brookings Institution

“Mustafa Akyol passionately engages in controversial and timely issues, builds upon a wide range of contemporary scholarship on Islam, and expands his well-thought arguments with supportive examples and interesting stories. This is a brilliant book.”

—Mariam Al-Attar, lecturer of Arabic heritage and Islamic philosophy at the American University of Sharjah

“Akyol puts forward a number of theses that will not sit well with the unflinching dogmatists of today, such as his emphasis that epistemological rationalism is neither new nor influenced by European rationalism; rather, it is a return to the way of the earliest generations of Muslim thinkers and titans.”

—Ahab Bdaiwi, university lecturer in formative and postclassical Islamic thought at Leiden University

“This is a hugely important book. Akyol has dared to destroy one taboo after another.”

—Murat Çizakça, professor of comparative economic history and Islamic finance at Marmara University

“An eye-opening history of minority scholars and movements in Islam who, from the beginning, called for the greater use of reason in theology and law and promoted pluralism and tolerance.”

—David L. Johnston, affiliate assistant professor of Islamic studies at Fuller Theological Seminary

“Akyol masterfully links the most debated issues in contemporary Muslim societies to their roots in the past.”

—Martino Diez, associate professor of Arabic language and literature at the Catholic University of Milan

“A clarion call to restore long-diminished traditions in Islamic thought.”

—Kirkus Reviews (starred review)

“The text is fluid, the ideas profound, and the book is recommended for any reader.”

—Booklist (starred review)

“Highly recommended for readers interested in Islamic religious thought.”

—Library Journal (starred review)

“Thoroughly researched and fervently argued.”

—Publishers Weekly

“Reopening Muslim Minds is a courageous and thoughtful book. . . . By pointing to the importance of the conscience as a measure of good and evil, Akyol calls our attention to the dignity of all human beings.”

—Gabriel Said Reynolds, professor of Islamic studies at the University of Notre Dame, in First Things

“It is rare to find in a single work a carefully documented intellectual history of Islam as well as a cri de coeur for contemporary reforms—or at least it is rare to find both tasks done well. Mustafa Akyol’s Reopening Muslim Minds, however, impressively achieves both feats with substance and elegance in a work that deserves to be acclaimed and widely read.”

—Karen Taliaferro, assistant professor at Arizona State University, in Religion & Liberty

“In this timely, engaging, and eye-opening book, Mustafa Akyol analyzes why the Muslim world got trapped in stagnation and underdevelopment, despite its early history of philosophical and social flourishing. An impressive case for a new ‘Islamic Enlightenment’ indeed.”

—Ahmet T. Kuru, professor of political science at San Diego State University

“Mustafa Akyol has identified some of the contours and mileposts leading to an ideal Islamic civilization that, if realized, might bring much-needed reforms and modernization to our culture.”

—Syed Amir, former assistant professor at Harvard Medical School, in The Friday Times (Pakistan)

ALSO BY MUSTAFA AKYOL

Islam without Extremes: A Muslim Case for Liberty (2011)

The Islamic Jesus: How the King of the Jews Became a Prophet of the Muslims (2017)

First published in the United States of America by St. Martin’s Publishing Group 2021

First published in Great Britain by Forum, an imprint of Swift Press 2022

Copyright © Mustafa Akyol 2022

The right of Mustafa Akyol to be identified as the Author of this Work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 9781800751712 eISBN: 9781800751729

To my beloved sons, Levent Taha, Efe Rauf & Danin Murad, so that they may grow up with both Islamic faith & universal ethics

Political Islam is only an aspect of the overall problem of Islam in the modern world.

—Ali A. Allawi, The Crisis of Islamic Civilization, 2010

The task before the modern Muslim is, therefore, immense. He has to rethink the whole system of Islam without completely breaking with the past.

—Muhammad Iqbal, The Reconstruction of Religious Thought in Islam, 1930

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

A NIGHT WITH THE RELIGION POLICE

A Visit to the “Inquisition”

“No Compulsion”—and Its Limits

A Matter of Enlightenment

1: A SELF-MADE MAN: HAYY IBN YAQZAN

An Individual Path to Wisdom

A Disappointment with the Religious

The “Inward Light” in the West

2: WHY THEOLOGY MATTERS

How It All Began

Are Tyrants Predestined by God?

A Theology of Justice, Freedom, and Reason

The Birth of Muslim Philosophy

The Fideist Reaction

A Soldierlike Obedience

3: ISLAM’S “EUTHYPHRO DILEMMA”

Divine Command and Human Reason

The Gap on Husn and Qubh

What Does the Qur’an Say?

Making Sense of Abraham’s Knife

The Ashʿarite Victory and Its Aftermath

4: HOW WE LOST MORALITY

A Case of Immoral Piety

Two Measures of Legitimacy

The Overinclusive World of Fatwas

The Shaky Grounds of Conscience

The Need for a Moral Revival

5: HOW WE LOST UNIVERSALISM

Two Views of Human Nature

Lessons of Slavery and Abolition

Human Rights vs. Islamic Rights?

Three Strategies: Rejection, Apology, and Instrumentalism 68

6: HOW THE SHARIA STAGNATED

Inheritance, Women, and Justice

The Decline of Ra’y

The Theory of Maqasid and Its Limits

Can Women Travel Now?

A Non-Ashʿarite Sharia

7: HOW WE LOST THE SCIENCES

Is There Really “No Contagion”?

A World with No “Causes”

Meanwhile, in Christendom . . .

The Rise and Fall of Muslim Science

What Is Geometry Good For?

Reason, Causality, and Ottoman Reform

A Leap of Reason

8: THE LAST MAN STANDING: IBN RUSHD

The Religious Case for Philosophy

The Incoherence of Ashʿarism

The Philosopher’s Sharia

A Reasonable View on Jihad

A Progressive Take on Women

A Precursor to Free Speech

A Tragic Loss

The Jewish Secret

9: WHY WE LOST REASON, REALLY

“Cancel Culture” Back in the Day

The “Anarchy” of the Muʿtazila

“Political Science” of the Philosophers

Ibn Khaldun, States, and Taxes

The Ashʿari Leniency to Despotism

The Divine Rights of Muslim Kings

From Earthly Despots to Heavenly God

10: BACK TO MECCA

A Contextual Scripture

Dealing with Arab Patriarchy

An Interactive Scripture

What Islam Initially Asked For

The Shift in Medina

The Statization of Islam

The Abrogation of Mecca

The Uses and Abuses of Fitna

11: FREEDOM MATTERS I: HISBAH

How to Beat Slackers and Pour Wine

The Evolution of the Muhtasib

A Matter of “Right and Wrong”

The Costs of Imposed Religion

12: FREEDOM MATTERS II: APOSTASY

Two Suspicious Hadiths

The Uses of Killing Apostates

Accepting the Golden Rule

13: FREEDOM MATTERS III: BLASPHEMY

How the Qur’an Counters Blasphemy

A “Dead Poets Society”?

No Compulsion in Religion—Seriously

14: THE THEOLOGY OF TOLERANCE

The Wisdom in “Doubting” and “Postponing”

“Preachers, Not Judges”

The Myth of the “Saved Sect”

Non-Muslims in Muslim Eyes

Who the Kafir Really Is

The Rings of Nathan the Wise

EPILOGUE

Acknowledgments

Notes

INTRODUCTION

A NIGHT WITH THE RELIGION POLICE

Anyone who can liberate the Malay Muslim mind is a dangerous threat. That is why the authorities had to censure Mustafa Akyol. They detained him, interrogated him and made his immediate future uncertain.

—Mariam Mokhtar, Malaysian journalist, Oct 20171

On September 21, 2017, I took the very long journey from the small town of Wellesley, Massachusetts, to Kuala Lumpur, the capital of Malaysia, with no clue about what awaited me in this far end of the world.

At that time, I was a visiting fellow at the Freedom Project at Wellesley College—an initiative aimed at cherishing classical liberal values, such as freedom of speech within American academia. What took me to Malaysia was also a liberal initiative, albeit one that operated within a very different milieu. Named Islamic Renaissance Front, or IRF, this was a small but vocal organization founded by faithful Malay Muslims who challenged the oppressive and intolerant interpretations of Islam in their country—with arguments from Islam itself.

My acquaintance with the IRF had a history. The organization had hosted me in Malaysia three times before, organizing seminars at universities, institutes, and other public venues. In 2016, it also published the Malay version of my 2011 book, Islam Without Extremes: A Muslim Case for Liberty. The founding leader of IRF, Dr. Ahmad Farouk Musa, was energized with the attention Malay Muslims were giving to foreign voices like mine. He just had a concern with the “Inquisition,” the seriousness of which I had not yet grasped.

On this trip, the first event on my schedule was a panel on how rational theology and philosophy flourished in early Islam and how their later decline marked an “intellectual suicide” that still haunts us—as we shall also see in this book. To an attentive audience, I argued that we Muslims need to revisit some of the ideas that have been banned to us as “heresy” for about a thousand years.

The next day, at another public venue in Kuala Lumpur, I spoke at the second panel on my schedule, which probed a sensitive topic: apostasy from Islam.2 It is a sensitive topic, because while you may think that anybody has the right to change his or her religion, quite a few Muslims believe that if the abandoned religion is Islam, the apostate deserves a death penalty. This punishment is applicable in about a dozen “Islamic” states, such as Saudi Arabia or Iran, where Malaysians are proudly more “moderate.” So, instead of executing the apostates, they send them to rehabilitation centers, where people can be held for six months, so that they can be “educated” and “corrected.”3

In my speech, I argued that apostates should be neither executed nor “rehabilitated,” but just left alone with their conscience. I referred to Islamic scholars who have reformist views on this matter, and also I reminded my audience of a Qur’anic phrase: La ikraha fi al-din, or “There is no compulsion in religion.”4 Yes, apostasy was condemned as a capital crime in classical Islamic law, I explained, but this only reflected the medieval norms according to which leaving the religious community also implied political treason. Times have changed, I noted, and our laws and attitudes must change as well.

In the same speech, I also added that if a Muslim loses faith in the religion, dictates would achieve nothing. For faith is a sincere conviction in the heart and mind that cannot be imposed from the outside. “Faith,” I emphatically said, “is not something you can police.”

Well, speak of the devil, as the saying goes, and he shall appear.

As the panel ended and I was getting ready to leave, a group of serious-looking men approached me. “Are you Mustafa Akyol?” asked one of them. I said, “yes,” wondering who he was. “As-salamu alaykum,” the man said. “We are the religion police.” Then he showed me his card, which defined his job really as “religion enforcement officer.”

The officers just wanted to “ask a few questions.” Supposedly, they had heard “complaints” about my speech, and now they were to investigate what I had said. “We got the recorded video of your talk,” the senior officer said. “We will watch it and then inform you about the next step.” He also asked me if I really quoted the Qur’anic phrase “There is no compulsion in religion”? I affirmed, “yes,” wondering why that could be a problem.

The officers also noted that they didn’t like my lecture planned for the next day—a conversation on my more recent book, The Islamic Jesus: How the King of the Jews Became a Prophet of the Muslims. Apparently the problem was the event’s subtitle, which read, “Commonalities Between Judaism, Christianity, and Islam.” “We don’t like that kind of stuff,” the senior officer plainly told me, making me recall the obsession in the country of drawing sharp boundaries between Abrahamic religions—to the absurd extent of banning Christians from using the word “Allah,” which Arab Christians have used for centuries without any question.5

Then, after this short interrogation, the religion police let me go, and I thought that was it.

The next morning, however, I woke up in my hotel room to read in the Malay media that I had been summoned to their headquarters—to the government ministry called Federal Territories Islamic Affairs Department, or, shortly, JAWI. My hosts suggested that we should cancel my last lecture and I should leave the country as soon as possible, to deal with JAWI’s questions through a lawyer and from afar. Following this advice, I packed my bags, bought souvenirs for my wife, and headed to the Kuala Lumpur International Airport. Around 8 p.m., I checked in and got my boarding pass. When I arrived at the passport control area, however, I realized that my adventure in Malaysia wasn’t yet over.

A VISIT TO THE “INQUISITION”

The female officer who looked at my passport turned a bit nervous when she put my name in her computer. “You need to wait, sir,” she said. She then called some police officers, who called other police officers, who soon escorted me to the police unit at the airport. There I learned that JAWI had issued a nationwide arrest order for me, to make sure I didn’t leave the country.

That was the beginning of a very long night. I was taken from the airport to a nearby police station, then to another official building, going through sluggish processes and also long distances around the unfamiliar Malay capital. Finally, toward 5 a.m., I was taken to the JAWI headquarters, where I was locked up in a detention room. No one was rude or harsh toward me, but the many unknowns were nevertheless distressing. I kept thinking about my children and my wife, who had given birth to our second son just weeks before my arrival in Malaysia.

In the morning, around 8 a.m., my door was unlocked and I was told that we were heading to the “Sharia court.” Finally, after another long drive and some waiting, I entered the court, which must have been the “Inquisition” that Dr. Musa had been talking about. I found two young veiled female officers sitting next to an older religious scholar with a long beard—a Hakim Syarie, or “Sharia Judge.” For two hours, they questioned why I came to Malaysia, who “abetted” me, and why I did not seek “permission” from the authorities in order to “teach Islam.” They were respectful, but also stern. And, astonishingly, they asked again with what authority I quoted the Qur’anic phrase “There is no compulsion in religion.”

Finally, there came the happy ending to this dark episode. I rejoiced to hear the sentence “We will release you.” “This is a lesson,” added one of the female officers, “so don’t come back to Malaysia again and teach Islam without permission.”

Soon, after eighteen hours under detention, I was let go. The first thing I did was call my wife, Riada. From her, I learned that what saved me was not mere luck. After Dr. Musa notified her of my arrest via phone, she immediately called Istanbul to alarm my father, Taha Akyol, who is a prominent Turkish public intellectual. He sought help from a few of his influential friends, the most prominent of which was Abdullah Gül, Turkey’s former president and a rare Muslim liberal democrat. Mr. Gül’s Istanbul office immediately got in touch with the office of His Royal Highness Sultan Nazrin Shah, a key ruler in Malaysia’s complex federal monarchic system. The Sultan’s advisor, Dr. Afifi al-Akiti, a scholar at Oxford University, soon contacted the court’s officials. Whatever was said apparently worked. Hours later, Dr. al-Akiti even kindly escorted me to my plane, on which this time I boarded without any trouble.

Yet still, days after my departure, the Malaysian government banned my book Islam Without Extremes along with its Malay edition, Islam Tanpa Keekstreman. The decision was announced by then deputy prime minister Ahmad Zahid Hamidi, who said the book was “not suitable to the societal norms here.”6 That initiated a long legal process, as the Islamic Renaissance Front went all the way up to the nation’s High Court to get the books unbanned. But in April 2019, the High Court upheld the government’s prohibition. In return, the Cato Institute in Washington, D.C., which I joined in September 2018 as a senior fellow focusing on Islam and modernity, offered the Malay edition of the book for free, soon to be downloaded by thousands of Malay readers.7 The Malaysian authorities were not giving up, so we would not give up, either.

“NO COMPULSION”—AND ITS LIMITS

What was it that alarmed the Malay authorities so much about my message? That question was in my mind right from the moment I was let go by the religion police. While seeking an answer, I recalled the bizarre detail in the interrogation: that they were annoyed at me for quoting the Qur’anic phrase “There is no compulsion in religion.” It is in a longer verse of the Qur’an, which, in its entirety, reads as follows:

There is no compulsion in religion: true guidance has become distinct from error, so whoever rejects false gods and believes in God has grasped the firmest hand-hold, one that will never break. God is all hearing and all knowing.8

While this verse has always been present in the Qur’an, the short clause at its very beginning took a life of its own in the modern era, providing a universal motto for liberal-minded Muslims. For in just a few simple words, it seemed to rule out any coercion in religious matters. True, the rest of the verse moved on to renounce “false gods” and to proclaim monotheism as “true guidance.” That is what religions do: they make a truth claim. But this truth claim remarkably came with a proclamation of “no compulsion,” or, in other words, freedom.

However, not all Muslims liked this Qur’anic freedom. I had seen some Saudi translations curtail it by inserting a few extra words, in parentheses, into the “no compulsion” phrase.9 When I checked the website of JAKIM, the Malaysian Department of Islamic Development, I found out the same thing. The “no compulsion” phrase was written like this:

There shall be no compulsion in religion (in becoming a Muslim).10

This little insertion in parentheses had huge consequences, for it reduced the “no compulsion” clause merely to allowing non-Muslims to stay outside of the faith. Those who are already Muslim, however, had no right to leave. They were also subject to coercion in the practice of the faith. This little stroke of a pen, in other words, gave the religion police its very authority to dictate Islam—the very authority I had challenged.

Yet, to be fair, this little stroke of a pen was also not unwarranted, because the “no compulsion” clause in fact had a limited meaning in the eyes of the premodern exegetes of the Qur’an, who built the mainstream Islamic tradition. Some argued that the verse was simply about a specific historic incident without any broader implications. Others suggested that the verse was only about not forcing Christians and Jews to accept Islam, but nothing more. Some even held that the “no compulsion” clause was “abrogated” by other verses of the Qur’an, which commanded war against “those who do not believe in God or in the Last Day.”11 Forcing people to accept Islam “with the sword” does not even count as compulsion, some also argued, because it is only for their own good.12

Moreover, a hadith, a saying attributed to the Prophet Muhammad, peace be upon him, further marginalized the spirit of the verse. “Whoever changes his religion,” it bluntly read, “kill him.”13 Whether the Prophet of Islam really said this is a good question we will probe in later chapters. But classical scholars took it at face value, reaching a “consensus,” or ijma, that the apostate must be executed—only after being given a few days to recant.

That is why the Malaysian authorities weren’t totally making things up by “editing” the translation of the “no compulsion” clause in order to limit its scope to only those who aren’t Muslim yet. They had the whole weight of the Islamic tradition behind them. In return, liberal Muslims like myself were pushing for something new.

A MATTER OF ENLIGHTENMENT

This story is not meant to discredit Malaysia. It is a beautiful country for which I still have a heart, a country that I would encourage anyone to visit. I also feel lucky that I had this experience there—and not in countries with much harsher laws, such as Saudi Arabia or Iran. Malaysia is indeed more “moderate” when compared to such religious dictatorships, where liberal critics can go through much darker experiences.

The problem isn’t about Malaysia, though. It is not about any other specific country, either. It is about an interpretation of Islam that is, by modern standards, authoritarian and intolerant. It manifests itself in laws and institutions that force women to cover their heads, or consider them lesser than men. It jails, flogs, or kills people for criticizing Islam and for even offering alternative interpretations of it. It demonizes Christians, Jews, and others, or even fellow Muslims who happen to be from a different sect.

Mind you: this is a separate problem from terrorism in the name of Islam, as practiced by armed groups such as ISIS, Al-Qaeda, or Boko Haram. Those terrorists are really “extremists,” in the sense that their wanton violence, which targets many fellow Muslims, as well, finds a very marginal support in the Muslim world. The problem of religious illiberalism, however, is not marginal. Suffice it to say that more than 60 percent of all Egyptians or Pakistanis believe that apostates must be executed or adulterers must be stoned.14

In the West, especially in the past few decades, this problem has attracted a great deal of attention, but its nuances often get lost in the tug-of-war between two opposite camps.

On one side, there are the apologists, who argue that there is simply no problem within Islam today. There are only a handful of extremists, they say, whose zealotry has “nothing to do with Islam.” They often have the good intention of defending Muslims from bigotry, but they do this by deflecting attention from real problems.

On the other side, there are Islamophobes, who cherry-pick all the problems within Islam today in order to depict the entire religion in darkest terms. They not only draw an unfair picture of the reality but also promote bigotry against Muslims, which helps only deepen the problem at hand.

So a more fair take on Islam is necessary, which can be helped greatly by a historical and comparative perspective.15 Islam is the last of the three great Abrahamic religions, and most problems we see in it today have also been present in the other two—Judaism and Christianity. The history of the latter, in particular, includes many episodes of coercion and violence in the name of God. It was only a few centuries ago that “heretics” or “witches” were burnt alive in Europe, and Catholics and Protestants shed each other’s blood. In those premodern times, Islam in fact proved to be a more lenient religion. That is why Sephardic Jews migrated to Muslim lands in 1492 to flee the persecution of Catholic Spain. That is why French philosopher Jean Bodin (d. 1596), who pleaded for religious tolerance, praised “the great emperour of the Turks,” who “permitteth every man to live according to his conscience.”16

Things began to change dramatically, however, with the Age of Enlightenment and its brightest creation: liberalism. New values, such as freedom of speech, freedom of religion, or equality before law, emerged, establishing a sense of human rights unmatched in any premodern civilization. Compared to them, the norms of the Islamic civilization looked growingly archaic.

To be sure, since the nineteenth century, some Muslims have taken significant steps to catch up. Recently, British historian Christopher de Bellaigue has summarized these efforts as the “Islamic Enlightenment.”17 Yet this very drive—including its authoritarian strains—provoked “Islam’s counter-Enlightenment.”18This is a reaction spearheaded by those whom scholar Khaled Abou El Fadl calls “puritans”—a wide range of Salafis, Islamists, and rigid conservatives—who act as the defenders of the Islamic orthodoxy against modern liberal values. For worse, they are often more assertive than the orthodoxy itself, due to both their reactionary nature and the newfound powers of the modern bureaucratic state.

This book is meant to be an intervention into this big crisis of Islam. It aims to help advance the Islamic Enlightenment, by presenting a comprehensive argument for it—and, perhaps more importantly, by dismantling the theological roadblock that obstructs it.

Yet I have an important point to stress: By “Islamic Enlightenment,” I really mean Islamic Enlightenment. In other words, I am not speaking about a wholesale adoption of Western Enlightenment, which had some dark spots of its own, such as Eurocentrism, racism, “white man’s burden,” or the illiberal secularism that grew especially in France. I am rather speaking about finding Enlightenment values—reason, freedom, and tolerance—within the Islamic tradition itself.

Luckily, those values really do exist within the Islamic tradition—yet often only as uncultivated seeds, forgotten paths, or even muted voices. And, as a great irony of history, those muted voices have been more impactful on another civilization: the Western world.

And right from that irony, now, we will begin Reopening Muslim Minds. We will go back to early modern Europe and look into a philosophical novel that fascinated British, French, German, and Dutch thinkers—a philosophical novel that was written centuries before by an Arab philosopher from Muslim Spain.

The cover of the 1708 edition of Simon Ockley’s English translation of Hayy ibn Yaqzan.

1

A SELF-MADE MAN: HAYY IBN YAQZAN

Enlightenment is man’s emergence from his self-imposed immaturity. Immaturity is the inability to use one’s understanding without guidance from another.

—Immanuel Kant, “What is Enlightenment?” (1784)

In 1671, Edward Pococke, the son and namesake of a famous Arabist at Oxford University, published a book titled Philosophus Autodidactus, or The Self-Taught Philosopher. This was the Latin translation of an Arabic-language manuscript that his father had encountered some forty years ago in Aleppo, where he worked as a chaplain to the Levant Company. At first sight, the book read like an adventure novel, but it was also a philosophical treatise demonstrating the power of human reason.

What Pococke expected from his translation, that we don’t know. But we do know that the book turned out to be a hit. Scholars visiting Oxford soon began begging for copies on behalf of colleagues abroad who had heard of it. The secretary to the British embassy in Paris, who introduced the book to scholars at the Sorbonne who “all read and approved it,” regretted that he ran out of copies to distribute. A Swiss colleague of Pococke’s asked for a copy for a French bishop who “impatiently expected it.”1

No wonder several reprints and other translations followed. In 1672, a year after Pococke’s Latin translation, the book came out in Dutch. Two years later, an English translation by a Scottish theologian was published, only to be followed by another English translation by a Catholic vicar in 1686, and finally a third translation from the Arabic original in 1708 by Simon Ockley, a professor of Arabic at Cambridge University. In 1726, the book also was published in German.

Philosophus Autodidactus did so well because it fascinated its readers. These included, even much before Pococke’s translation, Giovanni Pico della Mirandola, the key philosopher of the Renaissance who wrote the famous Oration on the Dignity of Man.2 Later fans of the book included “natural philosophers,” or scientists, as they were called at the time, such as Robert Boyle, who is largely regarded today as the first modern chemist, along with Enlightenment thinkers such as Baruch Spinoza and Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz. Some scholars think that the book may have inspired John Locke, the father of political liberalism, for his notion of tabula rasa, which envisions a free and self-authored human mind.3 Some also suspect an influence on the author Daniel Defoe, who, in 1719, published what is commonly known as the first English novel: Robinson Crusoe.4

In fact, some connection between Robinson Crusoe and Philosophus Autodidactus seems evident, because both books are about lone men living on uninhabited islands. The latter was just more philosophical, was written some six centuries earlier, and its author had a name less familiar to Western ears: Abu Bakr Muhammad ibn Abd al-Malik ibn Muhammad ibn Tufayl.

AN INDIVIDUAL PATH TO WISDOM

Ibn Tufayl (d. 1185/86), as he is shortly called, was an Arab Muslim polymath from Al-Andalus, the medieval Muslim kingdom in southern Spain. He penned treatises on medicine, only one of which survived, and also astronomy, in which he raised serious objections against the Ptolemaic system, which was the dominant model of his time. None of his works, however, have been as influential as the novel that would later make its way into Europe as Philosophus Autodidactus. The book’s original name, which was also the name of its hero, was Hayy ibn Yaqzan, or, literally, “Alive, The Son of the Awake.”

Hayy’s story, which we will now briefly see, begins on a wondrous Indian island, which “enjoys the most equable and perfect temperature of all places on the Earth.”5 It is full of beautiful plants and animals, but the first human who ever appeared on it, as a little baby boy, is Hayy ibn Yaqzan. Regarding his origin, which the author left unclear, we are introduced to two alternative theories. One is that men could come into life on this island “spontaneously without the help of father and mother.” The other theory is that a princess on a nearby island feared for the life of her baby and set him aloft—just like baby Moses—to reach a safe shore.

No matter how he appears on the island, the baby Hayy begins his life there all alone, only lucky to be suckled and adopted by a gazelle that we meet as “Mother the Roe.” As Hayy grows up, he begins to examine the natural world around him and to draw conclusions. He initially envies the animals for all the defensive weapons that they have but that he himself lacks—horns, teeth, hoofs, spurs, and nails. But then he realizes he has other gifts. His hands are capable of using tools, or making shoes and dresses from the skins of dead animals. He also realizes that he has the power to think, aim, and strategize.

When he is at the age of seven, his mother, Roe, the gazelle, gets fragile and finally dies. Devastated by grief, Hayy wants to do something to bring her to life, and, to that end, he wants to understand why she died. Finding no visible defect on her body, he decides to do that which had been a big taboo throughout the Middle Ages: an autopsy. He uses a sharp stone to dissect the body, and goes all the way to the heart and examines its cavities. Although he can’t bring Roe back to life, he figures out how the heart and the blood system work. By analogy, he begins to map out his own anatomy as well. When the body of Roe begins to decay, Hayy also learns from the ravens how to bury it—evoking the Qur’anic story of Abel and Cain.6

As he grows up, Hayy gets wiser and wiser, going through seven-year-long phases of maturation. He discovers more and more about the natural world through his evolving capacity for reasoned inquiry. He studies the limbs of animals and classifies them into kinds and species. He also begins to utilize the natural world by controlling fire, spinning wool, building himself a house and a pantry, domesticating birds to help him for hunting, or taming wild horses and asses. Thanks to all his observations and experiments, he acquires “the highest degree of knowledge in this kind which the most learned naturalists ever attained to.” In the words of an early twentieth-century French Orientalist, “This part of the novel forms a very interesting and ingeniously arranged encyclopaedia.”7

Then, at the age of twenty-eight, Hayy begins to focus on physics. He observes how water becomes vapor, discovering the transition from one form to another, recognizing that every transformation and motion must have a cause. Then he gets to the physics of the heavenly bodies. “He considered the motion of the moon and the planets from West to East,” we read, “till at last he understood a great part of astronomy.”

After all this, Hayy, who is now well in his middle ages, begins to ponder philosophy. What is the origin of all this amazing natural world? he asks himself, and entertains the two grand theories that were bitterly opposed at the time: that the universe was either created ex nihilo, or that it existed since eternity. “Concerning this matter he had very many and great doubts,” we read, “so that neither of these two opinions did prevail over the other.”

Not being a dogmatic person who would jump to conclusions without evidence, Hayy doesn’t end up with a verdict. “He continued for several years, arguing pro and con about this matter,” Ibn Tufayl tells us, as “a great many arguments offered themselves on both sides, so that neither of these two opinions in his judgment over-balanced the other.” So, on the question of the origin of the universe, Hayy remains skeptical, keeping a position of well-thought uncertainty that you would not see very often in the middle ages—and, well, not today, either.

Hayy does not end up skeptical on the question of God, though. He reasons that both of the cosmologies he considers point to the existence of a deity. If the universe was created ex nihilo, it certainly must have had a Creator. And even if it always existed, it still had to have a Prime Mover—a concept advanced by none other than Aristotle. So, eventually, Hayy gets convinced that there is a “necessarily self-existent, highest and all-powerful Being,” which he discovers not through any revelation, prophet, or tradition, but merely his own reason. He becomes a “knower,” in other words, more than a “believer.”8

Finally, Hayy develops a sense of ethics, too. Since there are no humans on the island, this comes out as care for the environment. He strives to attain the Creator’s compassion to living beings, by adopting an ascetic vegetarian diet and even caring for the well-being of plants. When he eats fruits, he always preserves their seeds. He also chooses “that sort of which there was the greatest plenty, so as not totally to destroy any species.” Such were the ethical rules, we read, “which he prescribed to himself.”9

A DISAPPOINTMENT WITH THE RELIGIOUS

When Hayy reaches the age of forty-nine, we come to an unexpected twist in the story: a surprise guest from another island.

This other island is not too far from Hayy’s secret paradise. But unlike the latter, it is full of human beings who have a religion of their own—a “Sect,” as Ibn Tufayl calls it. We are introduced to two men from this island—Salaman, who is the very prince of the place, and Asal, his good friend. The two men are fond of each other, but they are different. Asal is inclined to philosophy, “to make a deeper search into the inside of things,” as he also thinks that the scripture of his people’s Sect has hidden meanings that require interpretation. Salaman, in contrast, is a more simple man. He follows the scripture faithfully, keeping “close to the literal sense,” never troubling himself with different interpretations, and “refraining from such free examination and speculation of things.”

As his preference for solitary contemplation over the chatter of society grows, Asal finally decides to change his world. He hires a ship to take him to the uninhabited island of whose beauty he has heard before—the very island of Hayy. Soon after Asal lands ashore, the two men run into each other and both get very surprised. Hayy is all the more surprised, because he has never seen a human before.

The two men become friends. Asal teaches Hayy human language. When he learns his friend’s whole story, including the contemplations through which he discovered God, Asal is amazed, for he sees that “the teaching of reason and tradition did exactly agree together.”

Asal then tells Hayy his own story and the story of the people on his island. He tells about “the Sect,” or religion, his people believe in, whose teachings and practices all make sense to Hayy, who gets eager to see all those curious human beings. While Asal worries that this may not be the best idea, he can’t turn down his friend. Luckily, right at that moment, a wayward ship hits the island, giving the two men a chance to go to Asal’s homeland.

When they arrive at the city, Asal introduces Hayy to the people, telling his amazing story and praising his deep wisdom. Hayy sees that these common people are quite observant, that they keep “the performance of the external rites” of religion, but this does not stop them from “indulgence in eating” or other things he would consider immoral or unwise. So he begins to share his philosophical insights with the people of the island, only to find them too crude to understand. “He continued reasoning with them mildly night and day, and teaching them the truth, both in private and publick,” we read, “which increased their hatred towards him, and made them avoid his company.” The islanders were not bad people, Ibn Tufayl explains, but still,

Through the defect of their nature, they did not pursue it by the right path, nor ask for it at the right door, nor take it in the right manner; but sought the knowledge of it after the common way, like the rest of the world.

Hayy finally realizes that these people are hopeless, as “disputing with them” only “made them the more obstinate.” He also decides that the right guide for them is not their reason but their Sect. The ruler, Salaman, should continue keeping them “within the bounds of the law, and the performance of the external rites,” as it is better for them to “follow the examples of their pious ancestors and forsake novelties.”

At the end of this disappointing exposure to a religious society, both Hayy and Asal decide to leave it in this state of mediocrity, and go back to Hayy’s world. “Thus they continued serving God on this island,” Ibn Tufayl writes in closing, “till they died.”

THE “INWARD LIGHT” IN THE WEST

Hayy ibn Yaqzan, as a tale, was a good read, but that is not why it was important. Like some other powerful works of literature, such as Utopia by Thomas More or Animal Farm by George Orwell, it was a philosophical novel. It is, in fact, widely recognized as the very first philosophical novel ever written. Its purpose was to elucidate an idea—that man, through reason and inquiry, can both explore and utilize nature, while also figuring out the big questions about existence and ethics. The book was also a tribute to the individual—the rational individual—showing that he or she can find truth, in the words of a modern-day translator of the book, “unaided—but also unimpeded—by society, language, or tradition.”10

To some modern readers, these may not sound like spectacular ideas, and that is precisely because they are modern readers. We are living within modernity and are often taking its philosophical presuppositions as given. When Ibn Tufayl wrote his story, however, these precepts were quite unusual, if not revolutionary.

Their impact would be revolutionary, too. To get a sense of this, let’s take a closer look at Hayy’s path to the Anglo-Saxon world. The first English translation of the book, three years after Pococke’s Latin text, was penned by a Scottish Christian named George Keith. In his foreword to what he entitled as An Account of the Oriental Philosophy, Keith praised Ibn Tufayl, who, despite being an infidel, “hath been a good man, and far beyond many who have the name of Christians.”11 A few years later, in 1678, Keith’s friend and student Robert Barclay, in his book An Apology for the True Christian Divinity, also praised the story of “Hai Ebn Yokdan . . . a book translated out of the Arabick.”12

Neither Keith’s nor Barclay’s admiration for the book was accidental. They were missionaries of a new Protestant sect called the Religious Society of Friends—or, as they became more commonly known, the Quakers.13 A key element in the Quaker creed was, as it still is, the emphasis on the “inward light,” which “teaches us the difference between right and wrong, truth and falseness, good and evil.”14 Every human being had this inner light, Quakers believed, regardless of sect, religion, or race. Every human being, therefore, was equally valuable—an idea whose roots went back to the “Christian humanists” of the Renaissance.

For some other Christians at the time, who believed that light shines only within their church, this universalism was not appealing. When they saw the reference to Hayy ibn Yaqzan in Barclay’s Apology, they happily spotted the origin of the heresy. “Certain adversaries of Quakerism,” notes a contemporary Quaker source, “declared that Barclay drew his doctrine of the Universal and Saving Light from this work, a charge which one would think carried its refutation with it.”15 That is why Barclay’s reference to “Hai Ebn Yokdan” was removed from the later editions of the Apology. The “inward light” theology would continue without references to alien sources.

The theology did continue, though, quite successfully, making the Quakers the champions of what we today call human rights. William Penn, a Quaker leader, founded in 1681 the Province of Pennsylvania, which proclaimed religious freedom to all its residents, laying a prototype for the American Bill of Rights. In the next century, Quakers spearheaded the first antislavery organizations on both sides of the Atlantic. Under the leadership of one of their prominent friends, Benjamin Franklin, they became the first to petition the United States Congress for the abolition of slavery. Quakers also played a key role in establishing women’s rights, with their rigorous defense of education of girls and women’s right to vote. More recently, they have also been instrumental in setting up human rights organizations such as Amnesty International.

In contrast, we Muslims abolished slavery only thanks to the encouragement, even pressure, from Western governments—as we shall see in a later chapter. We still have a hard time accepting religious freedom—as the Malaysian religion police kindly reminded me. Some of us still frown upon the idea of equal rights for women. While our conservative scholars condemn “human rights-ism,” our authoritarian leaders who persecute their dissidents despise organizations like Amnesty International for interfering with our supposedly wonderful “domestic affairs.”

One wonders why. Why did the ideas articulated in Hayy ibn Yaqzan help trigger an intellectual revolution in Europe, whereas they remained feeble in the Muslim world?

To find an answer, we have to look deeper into the world of Ibn Tufayl, the world of medieval Islam. We have to see what this Muslim philosopher was trying to do with his novel and what the odds he was struggling with were. We have to see, more precisely, the stormy sea of theology on which he was trying to steer a battered ship of philosophy.

2

WHY THEOLOGY MATTERS

[In Islam] legal theory departs from the point where theology leaves off.

—Wael Hallaq, scholar of Islamic law1

If you ask a random Muslim today what brand of Islam he or she follows, the answer will probably come as either “Sunni,” or “Shiite.” The former answer is just nine times more likely, because nearly 90 percent of the world’s 1.6 billion contemporary Muslims are Sunni.

And how do the Sunni and Shiite visions of Islam differ? To outsiders, the answer may be surprising. For the big difference is not about the Qur’an or the Prophet Muhammad, which are held sacred equally by all Muslims. It is rather about who really was the rightful heir to the Prophet Muhammad as his first caliph, or “successor.” Sunnis approve what actually happened in history, honoring the first four caliphs—Abu Bakr, Umar, Uthman, and Ali. Shiites, in contrast, accept the legitimacy of only Ali and his later descendants. The big difference between them, in other words, is different versions of political history.

If you want to dig deeper, Sunnis, on which we will mostly focus in this book, can also tell you their specific madhhab, or “school”: Hanafi, Shafiʿi, Maliki, or Hanbali, all named after their founders, who all lived more than a thousand years ago. How do they differ? To outsiders, the answer may be again surprising. For these schools differ on things like whether shellfish is eatable or where hands should be placed during prayer—the practice of Islam, in other words, in all its minute details. Because they are schools of fiqh, or “jurisprudence,” which is the human effort to interpret the Sharia, or the divine law.

To be sure, there is more to Islam than political history and jurisprudence. There are also beliefs, or aqaid, about God, His attributes, His relationship with the world and human beings, and the latter’s place in the divine scheme. There is also a discipline that studies these beliefs called kalam. It literally means “speech,” but it roughly corresponds to the Christian concept of theology.

Yet kalam has little presence in Muslims minds today. If they are asked about it, most Muslims would be taken by surprise. They may vaguely know themselves as “Ashʿari,” or “Maturidi,” but with little sense of what these terms entail. Worse, if they try to learn more about kalam, religious leaders may advise them to avoid it. “Leave those debates to the ulama,” or “scholars,” one such scholar says. “Just hold on to the kalima,” which is the simplest declaration of the faith: “There is not god but God, and Muhammad is His messenger.”2

This faintness of theology, as we will call kalam from now on, among Sunnis is not an accident. Because, after the initial centuries of Islam, which were intellectually diverse and vibrant, there happened a “significant decline and marginalization of kalam among Sunnis.”3 Instead, jurisprudence became the primary discipline. As a result, Islamic culture became a “legal culture,” focusing on “proper behavior rather than proper belief.”4

Today, most Muslims are living within this legal culture, which entails a plenitude of dos and don’ts regarding prayer, fasting, almsgiving, ritual hygiene, dress code, dietary laws, family laws, and, most controversially, criminal laws. Non-Muslims also focus on this legal culture, because some of its rules conflict with the modern standards of human rights.

That gap between Islamic jurisprudence and human rights has led, for more than a century now, to various efforts at “reinterpreting” or even “reforming” Islam. Yet, while some steps have been taken, these efforts ultimately hit a rock-solid wall: the divine will, as decreed by the Qur’an and exemplified by the Prophet. Any discussion on whether Muslims should give up corporal punishments, respect free speech, or accept gender equality, for example, faces a strong “no.” No, because God and His Prophet said so and so.

But can we try to understand why God and His Prophet said certain things in a certain context? Can we figure out their intentions and then try to realize them in some other way, if we are in a different context? Moreover, besides religious texts, do we humans have a rational capacity to figure out what is right and wrong? And if we say “no” to this latter question, then how can we know the truth of religion in the very first place?

Such questions will take us from the realm of jurisprudence to what really lies beneath it, which is theology. The very realm, in other words, to which Muslims stopped paying attention centuries ago—although it still silently holds the barriers in their minds.

HOW IT ALL BEGAN

Islam, as the historical religion we know today, was born in the Arabian city of Mecca in the year AD 610. One night, Muhammad ibn Abdullah, a prominent merchant from the wealthy tribe of Quraysh, heard a strange voice in a cave that told him, “Recite.” First he was terrified, but thanks to his wife, Khadija, he got convinced that the voice was that of an angel. New revelations confirmed that he was chosen by God to share a dangerous message with his people: that their idols were all false gods. The only true God was “the Lord of the heavens and earth and everything between,” and who had sent other messengers before—men such as Noah, Abraham, Moses, or Jesus.5

This monotheist campaign soon put Muhammad and his small group of believers into trouble with the polytheist leaders of Quraysh. Hence, the thirteen years in Mecca, the first phase of Muhammad’s mission, passed under fear and persecution. The next phase began when the Prophet fled to Medina, another Arab city that welcomed him, in the year AD 622. The battles between the Muslims of Medina and the revengeful polytheists of Mecca, besides conflicts with shifting allies, went on almost until the very end of the Prophet’s life.

Hence, neither Prophet Muhammad nor his fellow believers had the time or the means to produce any literature. The only text that they left behind, besides a few short political treaties, was the Qur’an. After the Prophet, though, Muslim armies poured outside of the barren Arabian Peninsula to take over the more sophisticated centers of the ancient world, such as Palestine, Syria, Iraq, or Egypt, which had rich cultural and intellectual traditions. Eastern Christians in particular had a lot to offer. Their church fathers had wrestled with theological questions that would soon intrigue Muslims as well.

One of these questions soon turned out to be the first big theological controversy in early Islam: Did God create humans with free will? Or did He predestine their fate?

The Qur’an’s answer wasn’t very clear, but due to the enduring influence of pre-Islamic Arab beliefs, there was “a large element of fatalism or belief in predestination.”6 It was doctrinally defended by scholars who were ultimately called Jabriyyah, or “Compulsionists.” For them, all human acts occurred under the “compulsion” of divine predestination. God had simply created some for heaven, others for hell, and each were like “a feather hung in the wind.”7

But a minority of scholars disagreed, insisting that God gave humans free will—or qadar, meaning “power.” Their premise was God’s justice, which is reiterated throughout the Qur’an. To deprive humans from the freedom to choose and then to reward or punish them for their deeds, they argued, would be injustice, which God would not do. They were called Qadariyah, because they defended human “power” to act independently of God. (Yet later, the term qadar was associated with the power of God and became synonymous with predestination, so beware of confusion here.8)

The tension between these theologies was reflected in an interesting correspondence between Hasan al-Basri (d. 728), a highly respected scholar, and Caliph Abd al-Malik, a member of the Umayyad dynasty, which dominated Islam after the first four caliphs. The Umayyads were staunch supporters of Compulsionism. Hasan al-Basri, in contrast, was a defender of free will. “News has reached the Commander of the Faithful,” the caliph thus wrote, referring to himself, “that you would have made statements about the divine decree which are unheard of amongst those who have gone before us.” So he ordered, “Write to the Commander of the Faithful, explaining your position and whence you derive it.”9

A letter like that from an absolute monarch would give chills to most people. But Hasan al-Basri didn’t falter. He greeted the caliph with respect, then made his case. “God rewards His servants only on the basis of their works,” he wrote, explaining why this requires free will. Then he referred to the Qur’anic verses used by the predestinarians, adding:

However, Commander of the Faithful, things are not as these ignoramuses, in their error, maintain. Our Lord is too merciful and just and generous to behave like that with His servants. How could He act in this way, if we can read that, “God charges no soul save to its capacity; standing to its account what it has earned, and against its account what it has merited.”10

This correspondence between Hasan al-Basri and Caliph Abd al-Malik is the earliest document in Islam that deals with the controversy over free will.11 Some scholars doubt its authenticity and suggest that it may be apocryphal.12 Even if that is the case, it is an important text showing the early theological battle lines—and that the caliphate had a stake in them.

ARE TYRANTS PREDESTINED BY GOD?

We do not know how Caliph Abd al-Malik reacted to Hasan al-Basri’s response to his letter, if he had really received it at all. But we do know that the Umayyad caliphs, with a few exceptions, continued to promote the doctrine of predestination as a part of a “state sponsored orthodoxy.”13

Some scholars who defied this orthodoxy paid a heavy price. One of them was Mabad al-Juhani, who was executed by crucifixion around the year 700 for promoting free will, along with his role in an insurrection. Another one was Ghaylan al-Dimashqi, who had begun his theological work in the Umayyad court, only to become the “arch heretic” in early Islam. For the sole crime of championing free will, he was brutally executed in the year 743. First his hands and feet were amputated, according to one account, then he was hanged.14

One wonders why the Umayyad rulers were so obsessed with a deeply theological question. The answer is what you may guess: this theological question had political implications. Unlike the first four caliphs, who had come to power with some consultation in the community, the Umayyads had come to power by sheer force. Their founder, Muawiyah I, had fought with Ali, the fourth caliph, in the first fitna, or “civil war.” Muawiyah’s son, Yazid, brutally killed Ali’s son, Hussein, along with all his family members, in the horrendous massacre at Karbala. With all this violence, along with their corruption, nepotism, hubris, and Arab supremacism, Umayyads made many enemies.

In return, they needed all the support they could enlist—and there was no better supporter than God. First, they began to call themselves “Caliph of God,” instead of the more modest title, “Caliph of the Prophet.” Second, they used Compulsionism to insinuate that their rule was predestined by God. “These [Umayyad] kings,” as their victim al-Juhani said with contempt, “shed the believers’ blood, take their money, and then say, ‘our actions are ordained by God.’”15 One of these “kings” executed an innocent man, only to claim that he did “as was written in the book of fate.”16 Compulsionism was a perfect cover for all their misdeeds. Therefore, in the words of contemporary scholar Suleiman Ali Mourad:

In order to disseminate this ideology, the Umayyads enlisted in their service a number of religious scholars and poets whose task was to provide a religious defense of the predestination doctrine. It was these scholars who furnished a number of hadiths that depict the prophet Muhammad and his companions defending predestination and condemning freewill.17

In contrast to predestination, belief in free will led to the questioning of political authority: “If individuals were accountable for their actions, then were so governments.”18 That is why, throughout the Umayyad rule, the doctrine of free will was often connected with “agitating for a new political order.”19

The Umayyads ruled for about ninety years. After their fall, Compulsionist doctrine lost some of its impetus. Mainstream Sunni Islam, as we shall see, tried to develop a difficult middle position between predestination and free will—that there is predestination, but humans still “acquire” it with their free choice. “Human beings perform,” in other words, “the actions which God creates.”20 Yet this painstaking theological mishmash was necessitated by the invention of Compulsionist texts, especially hadiths by the Umayyads and their allies.21

Compulsionism would be used again and again, in different phases of Muslim history, including the modern times, to promote a fatalistic worldview that often helped those in power.22 These include Arab dictators such as Jamal Abd al-Nasser or Saddam Hussein, who, while owning their successes, repeatedly referred to fate “to rationalize defeat.”23 In face of the traumatic Arab defeat by Israel in the Six-Day War of 1967, Nasser had publicly evoked an Arab proverb, La yughni hadharun an qadar, or “Precaution or alertness does not change the course of fate.”24 As Arab scholar As’ad Abu Khalil observes, such “invocation of the notion of the inescapability of destiny” only helped “the absolution of Arab regimes and armies from any responsibility for the defeat at a time of mounting public criticism.”25