Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Batsford

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

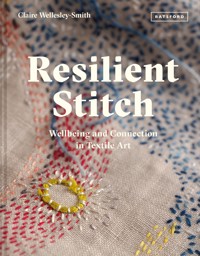

Following on from her textile hit Slow Stitch, author Claire Wellesley-Smith considers the importance of connection and ideas around wellbeing when using textiles. Claire explores textiles in the context of individuals and communities, as well as practical ideas around 'thinking-through-making', using 'resonant' materials and extending the life of pieces using traditional and non-traditional methods. Contemporary textile artists using these themes in their work feature alongside personal work from Claire and examples from community-based textile projects. The book features some of the very best textile artists around, esteemed American fiber artists and the doyenne of textiles, Alice Kettle. Resilient fabrics that can be manipulated, stressed, withstand tension and be made anew are recommended throughout the book, as well as techniques such as layering, patching, reinforcing, re-stitching and mending, plus ideas for the inclusion of everyday materials in your work. There's an exploration of ways to link your emotional health with your textile practice, and 'Community' suggests ways to make connections with others in your regular textile work. 'Landscape' has a range of suggestions and examples of immersing your work in the local landscape, a terrific way to find meaning in your work and a sense of place. Finally, there is a moving account of one textile community's creative response to the 2020 coronavirus pandemic. The connection between wellbeing and the creation of textiles has never been stronger, and, as a leading exponent of this campaign, Claire is the perfect author to help you find more than just a finished textile at the end of a project.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 106

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

Introduction

Material

Community

Environment

History

Conclusion: a resilient textile

Postscript

Notes

Bibliography

Contributors’ websites

Acknowledgements

Picture credits

Stockists

Index

Introduction

I am an artist and researcher based in the North of England with a practice focused on long-term engagements with communities. These projects use textiles as conversation starters and, through practical and creative activities, as a ‘way in’ to consider links between mental and physical health, to explore heritage and place, stories of arrival and belonging, and community cohesion. West Yorkshire, where I live, is an area rich in textile heritage and this heritage forms a central part of my working life. I use archives from the industrial production of woollen and cotton textiles that dominated this region to inspire project work and bring stories back into conversation with communities. Recent work has involved exploring the textile-dyeing and recycling industries, looking for and finding stories in the waste, the leftovers, the worn and the discarded. These projects also offer an opportunity to consider the implications of our current relationship with textiles, particularly the challenging issues around the production and consumption of cloth in the 21st century. They offer an opportunity for honest conversations that take place alongside making, remaking and repairing activities with diverse groups of people. My practice has informed the thinking behind this book. In my own work I explore ideas through simple processes that engage with the locations I live and work in. These include a daily stitch practice that embodies my textile and other thinking, and the growing and processing of dye plants to produce local colour on cloth.

Thinking about resilience

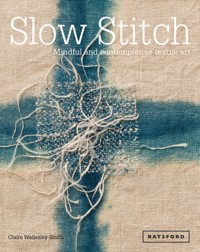

Since 2010 I have been interested in the word ‘resilience’ and how it is applied in many different scenarios, but also its strong link to materiality. My first book Slow Stitch: Mindful and Contemplative Textile Art (Batsford, 2015) encouraged taking a thoughtful and meaningful approach to textile practice, using less-is-more techniques and valuing quality over quantity. It explored time as a material and included work by me and other artists that engaged with seasonality and community in the context of ideas from the Slow movement. I hope to extend some of these themes here and consider the importance of connection for individuals and communities when engaging with textiles. Practical ideas around ‘thinking through making’, using resonant materials and extending the life of pieces using traditional and non-traditional methods are included. Contemporary textile artists consider what the word resilient means to them and share examples from their practice. These feature alongside my own personal work and examples from community-based textile projects.

How to use this book

This book considers resilience, its multiple definitions and uses, and will look at it through materials-based discussion and textile art practices. It is not a project-based book; rather it offers ideas and strategies for considering the materials and processes that might make a ‘resilient’ textile. Processes include piecing and patching, making and unmaking, mending, tying and binding, revisiting old work and growing colour. I look at resilience through a number of themes: through materials, the environment, history and community. The processes explored are not simply ones that happen when we work on fabric or with other textile activities. Rather they speak of dialogue, with materials and with other people, and in many different communities and settings.

Resilience

Tending to resume the original shape or position after being bent, compressed, or stretched; hard-wearing because of being able to recover after the application of force or pressure.

Of a person, the mind, etc.: tending to recover quickly or easily from misfortune, shock, illness, or the like; buoyant, irrepressible; adaptable, robust, hardy.

Oxford English Dictionary

Resilience is a word that can be defined and used in different ways, mostly in terms of a capacity to recover quickly from difficulties, or to describe a substance or object and its ability to ‘spring back’ into shape. It is a complex concept and has come to the fore in recent years to describe a number of scenarios. Sometimes used in the context of a societal process, it has also become a process and aspect of research of its own. In policy fields it is used in discussion of diverse issues from climate change, population growth and poverty reduction to urban planning. In healthcare settings it is extensively used in the language around mental health and also preventative action. In self-help books and inspirational mantras, the word often appears. From grassroots campaigning to central government policy, the word ‘resilient’ crops up time and again. In a time of huge changes in society and the environment there is also the need to process these changes. So perhaps the use of this word in so many contexts is indicative of this need. It is also regularly critically appraised, criticized for allowing organizations or underfunded systems using the concept to avoid responsibility, placing the onus on the vulnerable to adapt to difficult situations.

Community quilt being made by participants at the Sukoon-e-Dil group, Roshni Ghar Project in Keighley, West Yorkshire.

Resilience (2010). Altered discarded book, paper, stitch, recycled textile. 12 × 20 × 4cm (4¾ × 8 × 1½in).

I began to think about the word and its meanings in 2010 while working on a long-term arts and health project that offered participants opportunities to engage with green spaces and creative work. Projects took place in community gardens, mental health organizations and hospitals. Resilience was a word often used in project sessions, where there were conversations around wellbeing, strategies for managing life’s complexities, and how a craft practice might help with this. At some stage during this project I made an adapted book using a disintegrating hardback bought at a charity shop. I repurposed it with the word ‘Resilience’ at its centre, patched textiles and sketches addressing my personal and working life at the time. The book is messy and incomplete, pages painted with gesso to blank out the text, the fabrics used repurposed from baby dresses worn by my young daughters. The adapted book has stayed on the shelf in my studio, sometimes taken out as a teaching sample. It now mainly serves as a reminder of the tenacity of materials and the messiness of life, and as an object with resonance for me. The security of the stitched and bound pages, tied together with handmade string, gather and hold my thoughts from that time.

More recently I have considered ideas of resilience and how they might relate to textiles during an academic research project with The Open University. This looks at how community-based slow craft projects, connected to the heritage of a place, might have an impact on the resilience of the communities based in these areas. Across the North of England, the textile industry, the woollen industry in West Yorkshire where I live and cotton in Lancashire where I often work, remains a feature in the landscape, although much of the industry is now gone. The geography of the areas was a huge influence on the industry being here, the climate and soft water conducive to textile manufacture. The collective industrial work and the processes of working with raw materials, spinning, weaving, dyeing and printing was done by communities that moved for the work, firstly from rural areas to the newly enlarged towns and cities, then from all over the world. These communities have experienced huge changes in the last 40 years, in employment, in income and in health: in many cases deindustrialization has brought with it great disadvantage. My projects in former industrial manufacturing areas involve talking about and making textiles with many people who bring materials-based reminiscences to share. Working with adults in arts and health settings, with intergenerational projects and with those experiencing ill health and disability, has also made me question ideas around resilience.

When I first studied textiles, one of the things that fascinated me about the fabrics I was working with, and was beginning to understand, was their flexibility, their stretch. In On Weaving the artist Anni Albers describes cloth as ‘the pliable plane’1. I would take a plain cotton handkerchief square and twist it, pull at the corners, briefly distorting the warp and weft, roll it up, cram it into a ball, pleat it, knot it, gather the points together to carry another object. All of these actions could be performed just using the hands, without need for a pair of scissors or needle and thread, to transform the shape or the potential use. After these interventions, the fabric could be smoothed out by hand again, leaving the square pretty much unaltered. If one changed the fabric composition, to something with stretch or with a looser weave, then this process would create different results. Depending on the flexibility of the fibre, marks of the activity would either be left or not, the fabric usually resilient. Later, as my practice developed, I considered the porosity of cloth, working with large lengths of industrial wool and saturating them with dye. I was interested in how the cloth performed, and how, when dry, it resumed its function.

Dyer’s Field (2015). Recycled wool, found dyes. Installation view as part of ‘Material Evidence’ exhibition at Sunny Bank Mills, Leeds, West Yorkshire. 3 × 1.5m (9¾ × 5ft).

Manipulating a cotton handkerchief to test flexibility.

I also covered large areas of fabric with multiple stitches that pierced and interrupted the cloth, considering the contraction and manipulation of the surface. Julia Bryan-Wilson, writing in Fray: Art and Textile Politics (2017) uses the capacity of textiles to be pulled, stressed, and withstand tension ‘sometimes to their breaking point’2, as a way into a discussion of the tensile properties of textiles, and how this can also connect to the politics of cloth.

When running projects that engaged with stories from the rich textile heritage of Northern England, exploring a period when every fragment of cloth was precious, I also thought about the physical properties of the materials made and used. These projects looked at the impact of industrial textile production: from the miles of cloth emerging from local textile mills to lesser-researched processes, those around the ‘end use’ of fabric, clothing and fibre. A community engagement project, ‘Worn Stories: Material and Memory in Bradford 1880–2015’, looked at the histories of textile recycling, repair and reuse in the city, both domestic and industrial. As part of the research for this project I viewed archive samples of fragile textiles, those worn by age, use or sunlight, and rendered brittle, frayed and broken as a result. I also began to collect much-worn samples of cloth and clothing myself, sometimes working them into new objects, sometimes keeping them in their existing precarious state. Their survival seemed miraculous to me, small pieces or garments that could have been so easily lost to time. I see these as resilient objects and that they have the capacity to be made stronger again, through various processes. These could include formal restoration techniques, such as layering with other fabrics, mending using traditional and less traditional techniques, and stitching for reinforcing. Left as they are in their fragile condition, they carry stories of their use, evidenced through threadbare sections, visible darns and other mending. Around the same time, during an artist’s residency at Gawthorpe Textiles Collection in Lancashire, I found examples of much-repaired stockings and darned baby bootees among rare collections of silk-embroidered pockets and handmade lace. The collection of Rachel Kay-Shuttleworth offered an interesting and unusual insight into collections of everyday textiles from the local community. These evidence ordinary life and the need of families to preserve their textiles for the longest time possible.

Unpicked cotton shirt pocket found as a layer in the interior of a quilt.

Baby bootees found outside a textile recycling plant in Bradford, West Yorkshire.

Salvaged unfinished patchwork piece, overdyed with indigo.