18,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

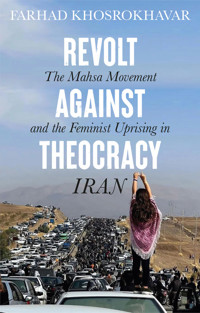

This book is the first in-depth account of the uprising in Iran that began on 16 September 2022, when a young woman, Mahsa Amini, was killed by the morality police. In the months that followed, protests and demonstrations erupted across Iran, representing the most serious challenge to the Iranian regime in decades.

Women have played a key role in these protests, refusing to wear a hijab and cutting their hair in public to chants of ‘Woman, Life, Freedom’. In Farhad Khosrokhavar’s account, these protests represent the first truly feminist movement in Iran, and one of the first in the Muslim world, where women have been in the vanguard. There have been many movements in the Muslim world in which women have taken part, but rarely have women – and especially young women – been the driving force. The Mahsa Movement also championed non-Islamic, secularized values, based on the joy of living, the assertion of bodily freedom and the quest for gender equality and democracy.

Khosrokhavar gives a full account of the context of and background to the events triggered by the killing of Mahsa Amini, analyzes the character of the Mahsa Movement and the regime’s repressive response to it, and draws out its broader significance as one of the most significant feminist movements and political uprisings in the Islamic world.

Now available as an audiobook.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 427

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Cover

Table of Contents

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Preface

A note on terminology and data

Notes

Introduction

1. The mindset of the younger generation: the new culture of “joie de vivre” against Islamic theocracy

The false piety of the parents and the provocative sincerity of their children

The new generations and the dismissal of the “Islamic patriarchal pact”

The opposition to the Theocratic State

Repudiating the Shi’i culture of grief and espousing the secular culture of “joie de vivre”

The secular culture of “joie de vivre” and the rejection of the culture of martyrdom

The cultural abyss between State and society

The cultural prominence of the secular middle classes after decades of Islamic theocracy

The everyday life of the impoverished middle classes

The “would-be middle-class” individual

Shunning of the Mahsa Movement by the working classes

The new ethnicity

Notes

2. Protest movements before the Mahsa Movement

A century of female presence and the lack of a feminist social movement in Iran

Historical reminder of the veil

Notes

3. The Mahsa Movement: the first sweeping feminist movement in Iran

The peculiar features of the Mahsa Movement

Women as pioneering social activists

The body and its language as the focus of symbolic forms of protest

The global civil sphere (GCS)

Notes

4. The new intellectuals

Three generations of feminist intellectuals since 1979

Young female activists in the September 2022 protests

The pop singers and sportsmen and women as the new intellectuals

Notes

5. From a theocratic state to a totalitarian one

The crackdown on protest movements as a central mission of the totalitarian state

Forms of repression

The Islamic Regime’s view on unveiled women and young protesters

Notes

6. Secularization counter to the Theocratic State

The secularized family as a bulwark against the Islamic theocracy

Forbidden leisure

The Iranian diaspora and its cultural role in Iran

Manoto TV

Notes

Conclusion

Notes

Index

End User License Agreement

Guide

Cover

Table of Contents

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Preface

Introduction

Begin Reading

Conclusion

Index

End User License Agreement

Pages

iii

iv

v

viii

ix

x

xi

xii

xiii

xiv

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

158

159

160

161

162

163

164

165

166

167

168

169

170

171

172

173

174

175

176

177

178

179

180

181

182

183

184

185

186

187

188

189

190

191

192

193

194

195

196

197

198

199

200

201

202

203

204

205

206

207

208

209

210

211

212

213

214

215

216

217

218

219

220

221

222

223

242

243

244

245

246

247

248

249

250

251

252

253

254

255

256

257

258

259

Revolt Against Theocracy

The Mahsa Movement and the Feminist Uprising in Iran

Farhad Khosrokhavar

polity

Copyright © Farhad Khosrokhavar 2024

The right of Farhad Khosrokhavar to be identified as Author of this Work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

First published in 2024 by Polity Press

Polity Press65 Bridge StreetCambridge CB2 1UR, UK

Polity Press111 River StreetHoboken, NJ 07030, USA

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purpose of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

ISBN-13: 978-1-5095-6451-4

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2024930040

The publisher has used its best endeavours to ensure that the URLs for external websites referred to in this book are correct and active at the time of going to press. However, the publisher has no responsibility for the websites and can make no guarantee that a site will remain live or that the content is or will remain appropriate.

Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition.

For further information on Polity, visit our website:politybooks.com

Dedication

This book is dedicated to the young women and men who have chosen to fight and even die for freedom and equal gender rights against the Islamic Republic in Iran.

Preface

The first thesis presented in this book is that the Mahsa Movement is most probably the first genuine, global, and extensive feminist movement in Iran ever, and perhaps in the Muslim world. This is not to deny that women have played a significant role in social movements in Turkey, Egypt, Syria, Iran, and other Muslim countries since the nineteenth century. But within these movements, women were not in the vanguard, did not become the main actors, did not express their feminist demands in clear antagonism towards the powers that be, and men did not follow them en masse.

In the Mahsa Movement young women played a pioneering role not only in launching the movement, but also in their participation throughout. The protests quickly spread among young men, who showed that they largely shared the women’s views on the veil, on equal gender rights, and the rejection of theocratic rule. The movement was, in a sense, the apogee of what had begun the day after the establishment of the Islamic Republic in Iran with the imposition of the veil and, subsequently, the application of Sharia law, which spelled out the structural inferiority of women in terms of rights. But the movement also represents a break with prevailing trends in Iranian feminism, notably in terms of the explicit and direct rejection of the veil and the Islamic Regime, as well as in the affirmation of a new culture based on the joy of living and the unvarnished, uninhibited secularization expressed throughout the movement without any reference to religion.

What essentially characterizes a global feminist movement is the primordial role played by women, where the major slogans and demands refer explicitly to women. In the Mahsa Movement, these conditions are certainly met: the slogan “Woman, life, freedom” sets the tone, the role of women at the vanguard is undeniable, and in addition, young men participated actively in it. When in March–April 2023 the movement lost its ability to mobilize groups, individual women continued in the struggle, by rejecting the compulsory veil.

While women were the trailblazers in the protest movement, young Iranian men conscientiously played an ancillary role by putting into question their masculine pride founded on patriarchal, traditional Islam – their male “Islamic honor” so-called (gheyrat in Persian, gheyra in Arabic). The distinctive feature of the Mahsa Movement was not only that young women rebelled against their subaltern role – in many movements throughout the Muslim world women have revolted time and again in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries against their inferior condition – but that the young men joined them without ulterior motive, recognizing their legitimacy and their role as foremost denouncers of the Islamic patriarchy and theocracy.

The Mahsa Movement has two essential characteristics: the quest for gender equality and the denunciation of dictatorship. This book seeks to analyze the mindset of the young men but also, and especially, of the young women within the movement and their conflictual relationship with a patriarchal state that denies them equality and the freedom to own their bodies. The movement began mid-September 2022, called here the Mahsa Movement after the first name of the young Iranian woman, Mahsa Amini, killed by the Vice Squad in Tehran on September 16, 2022. In cooperation with young men, women challenged the Theocratic Regime for several months.

The second purpose of this book is to depict the political and ideological features of the Islamic State that has ruled the country since 1979 and its distorted relationship to society. I call it a “soft” totalitarian regime: it stifles social protest but is unable to prevent its rise. This book describes the multiple forms of the State’s repression through its central organization, the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC), through the clergy, and through the repressive organizations under their aegis (official and unofficial prisons, militia, the Basij Resistance Force, etc.). Arbitrary arrests according to the formal Iranian Constitution, torture, sequestration, and execution are the arsenal of this state, which acts promptly to stop non-violent protest movements. It survives because it crushes unorganized, leaderless protesters; it prevents their organization and progress by ruthless repression, breaking them through extreme violence.

The book focuses on the emergence of new social activists. First are the women themselves, whose forebears – often leading feminist intellectuals – have raised the awareness of the younger generations, and paid a heavy price through imprisonment and systematic mistreatment, even psychological and physical torture. They have provided the new generations with a body of feminist literature and social movements (for instance, the Campaign for One Million Signatures in 2006) that have left their imprint on the young women who are risking their lives to demonstrate in the streets of Iran.

Meanwhile a new type of intellectual has emerged, comprising hip-hop, rap, and blues singers, who have become the “organic intellectuals” of the latest protest movement. The book points also to the influence of the diaspora, through TV channels and the internet, in shaping the culture of Iranian youth. The latter reject the Theocratic State and its repression and total disregard for their aspirations.

The book also underlines the secular culture of the new generations, which I call “joie de vivre” (zest for earthly life). It is centered on this world’s pleasure and daily life, and not on a sacrificial afterlife in the name of martyrdom which underpins the ideology of the Islamic Republic. In this new culture, free and secular relations between men and women, the desire to enjoy life in this world and not in the hereafter, as well as the rejection of the “mournful culture” of the Islamic Regime, are emphasized. The culture of joy is expressed in opposition to the Theocratic Regime’s ideology in a festive but also transgressive way, of which dancing, partying, and the ostentatious female unveiling in public are prominent aspects.

In the protest movements that have unfolded in Iran since 2009, the middle classes have played a decisive role. But they have been undermined by the decline in their living standards. The Islamic Regime has debilitated them through its economic policies, and not least the general crisis of the Iranian economy has taken its toll due to its exclusion from the world economy in consequence of the country’s nuclear program. A large part of the population could be said to be middle class in terms of culture due to the overall increase in the level of education, but it does not have the economic status corresponding to its expectations as aspiring middle-class members. I call them “would-be middle classes.” In this group, their adverse economic status in conjunction with their secular culture pits them directly against the Islamic State, which disapproves of meritocracy and is driven by cronyism, deep-rooted corruption, and prohibitions on bodily freedom and gender mixing in the name of orthodox Islam. Its clash with the young would-be middle classes is head-on.

The would-be middle classes have a half-imaginary, half-real construction of a global, worldwide civil sphere. They take it as witness to the legitimacy of their struggle for freedom and the illegitimacy of a state that denies them the most elementary freedoms. The protagonists in the fight against women’s inequality are recognized and awarded for the defense of freedom by the international institutions that represent the global civil sphere. Reference to the wider world is one of the hallmarks of the Mahsa Movement.

This book aims to show the vigor of secularization in Iran despite the Islamic State’s unrelenting endeavors to turn its citizens into submissive Muslims through its state apparatus (national education, the official TV and radio networks, the propaganda machine sustained by the government). Secularization has occurred against a rigid form of Shi’ism that I term theocratic Shi’ism, which is the ideological cornerstone of the Islamic Republic. It shows major differences with traditional Shi’ism. Theocratic Shi’ism places special emphasis on martyrdom and mourning in the service of a theocratic state and its purpose is to legitimize the domination of society by the Velayat faqih (the absolute rule of the Supreme Leader). It justifies the constraints imposed by the government: the compulsory veil, segregation of men and women, prohibition of alcohol consumption, respect for Ramadan fasting, prohibition of celebration and dancing in public, opposition to the West in the name of a politico-religious conception imposed on society and not open to debate, and so on. In most cases, what was flexible in traditional Shi’ism has become rigid and unyielding under theocratic Shi’ism.

The Islamic Republic has failed to de-secularize society and this book seeks to explain why. The widespread protest movements since 2009 are analyzed in this respect. The Mahsa Movement of 2022–3 has shaken the Islamic Regime but has failed to overthrow it. It has succeeded, culturally and socially, in showing the Regime’s illegitimacy, and women continue to reject the mandatory veil by appearing unveiled in public. The book underlines the recurrence of the protest movements, despite the harshness of the repression, leading to the wearing down of the Theocratic State.

This book highlights the continued action of a predatory state that represses its citizens in everyday life, and whose elite enriches itself by indulging in illegal practices that it forbids to the population. It allows itself every kind of abuse, and its very existence is a denial of dignity to its citizens (and is perceived as such by a large majority of them). It is based on a theocratic version of Shi’ism which is different from the traditional one in many respects, and that are described at length in this book. An increasingly secularized society rejects the Regime’s religious and political claim to govern it. But for the time being, citizens do not succeed in overthrowing it for lack of organization and leadership.

A note on terminology and data

In this book, the Islamic Republic in Iran is referred to variously as the Islamic Regime, the Theocratic State, the Islamic Republic, the Regime, and sometimes, the predatory state in reference to its ruthless, violent action against its citizens.

The protest demonstrations, which began in mid-September 2022 and continued up to February/March 2023 and beyond, have been alternately called a movement (harekat), an uprising (khizesh), a super-movement (abar-jonbesh)1, a female revolution (enqelab zananeh), and a peace revolution (enqelab solh)2. While I have chosen to call it the Mahsa Movement, it has also been called the September 2022 Movement3 or the Jina Movement (Jina being the Kurdish first name of Mahsa Amini).

Several expressions have been introduced to translate the Persian terms regarding how the veil is worn: “de-veiling” or “unveiling” (kashfe hejab), unveiled or “veil-less” (bi hejab), “mal-veiled” or “badly veiled” (bad hejab), or “loosely veiled” (shol hejab).

Translations from Persian and French texts into English are mine, unless stated otherwise.

It should also be noted Iranian statistics have been subject to vigilant censorship since at least 2009 and are not always reliable. Data on human rights in Iran can be found on the websites of Hrana (Human Rights Activist News Agency), https://www.en-hrana.org, Iran Human Rights Society, https://iranhrs.org/, and Iran Human Rights Watch, http://iranhrw.com/

The research for this work ended in July 2023.

Notes

1.

Mehrdad Darvishpoor, “The spark of the explosion of a ‘super movement’ and ‘women’s revolution’ in Iran?” (

Jaraqeh efejar “abar jonbesh” va “enqelab zananes” dar iran?

), BBC Persian, September 22, 2022.

2.

Song by Amir Tataloo, “Peace Revolution” (

Enghelab solh

),

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YuYvHaOF8Qw

3.

I was one of those who called it by the date of when it began. See Farhad Khosrokhavar,

L’Iran: La jeunesse démocratique et l’Etat prédateur

[Iran: The democratic youth and the predator state], Fauve Publishers, Paris, 2023.

Introduction

Anew subjectivity characterizes the younger Iranian generation which the Islamic Republic does not understand at all. The Theocratic Regime is the target of their hatred because it is the major obstacle to their self-realization, to their desire to be recognized in their dignity as citizens, and to live their lives to the fullest in a secular, joyful life in this world, disregarding the grim view of life imposed from above in the name of Islam. Paramount is the mandatory veil, which is an assault on the body of the young women who do not want to wear it. There are, of course, economic, political, and social motives that also play an important role in the protest movement of 2022–3. The Regime failed to offer decent living prospects to new generations, whether economically, politically, or culturally. It robbed them of their freedom in the name of a conservative version of Islam. It denied them access to modernity and its inherent desires (deciding what one wears, being able to travel and meet friends without fear of being arrested and abused, recognition of one’s competence, having the right to a fair future). The new subjectivity, especially among young women, does not recognize an intangible sacred rule from above, and more generally, rejects any norm that hinders their desire to live their life freely, to be in control of their own personal destiny – in short, to have no religious guardian. There is an unfathomable abyss between the Theocratic Regime and its youth. It deliberately ignores or even despises their demands and believes that it can subdue them through intimidation, repression, and, ultimately, death. However, its capacity for intimidation has limits, and two strategies are available to the youth: either violating on the sly repressive standards that are light years away from their aspirations, or collectively protesting when the opportunity arises.

It should be noted that workers did not play a significant role in the Mahsa Movement. There is a great deal of worker discontent in Iran as a result of wages not keeping pace with inflation and the breaches of economic fairness for the working classes. But precisely because of their poverty and the absence of a culture of radical protest, workers’ movements have confined themselves to sectoral demands, and they did not play even a supporting role in the Green Movement in 2009 or in the Mahsa Movement in 2022–3. The many and varied workers’ protests, whether at the Sherekat Vahed urban bus company or the Haft Tappeh sugar plant in Khuzestan (southwest Iran), or among oil and steel workers, focused on economic demands, without calling into question the political nature of the Islamic Regime. Meanwhile other types of protest movement played a role in the Mahsa Movement, namely among ethnic minorities (Kurds, Baluchi, Iranian Arabs, etc.), Muslim religious minorities (the Sufi Gonabadi dervishes in Tehran, the Iranian Sunni Muslims, who are discriminated against, especially in the underdeveloped southeastern province of Sistan and Baluchistan), the Baha’is (who are not even recognized as a religious minority and are systematically repressed and denied their elementary rights under different pretexts), citizens exposed to pollution and sandstorms (in the city of Ahvaz in the southwest of Iran, among others) or to the drying up of lakes (such as Lake Urmia in the northwest of the country) or rivers (Zayandeh Rud in Isfahan) or subject to water shortages, and especially students, who are systematically repressed in their desire for freedom of expression and gender equality.

The Mahsa Movement is the crowning achievement of these acts of protest. It has been driven by the will to overthrow the Theocratic Regime and establish a democratic one. But at its heart it is a profoundly cultural revolution, namely against what can be called traditional Shi’ism with its tragic vision of existence that the Islamic Regime has tried to exploit mainly through the cult of martyrdom. The movement has been centered on women because they are the focus of traditional Islam, which targets them as the symbol of fertility that must be desexualized and therefore covered by a veil in public and segregated from men other than husbands and fathers. Juridically, women weigh half as much as men. The movement challenged the inferior status of women, who freed themselves from the mandatory veil and segregation and asserted themselves as equal to men in daily life, by participating in the festivities on the streets where men and women came together and as joyful citizens danced, sang, and feasted. The Mahsa Movement has been therefore in direct conflict with the values of Islamic culture and its theocratic version that has become the ideology of the Islamic Republic.

The Mahsa Movement was marked by the activism of young women and the willingness of young men to follow them in confronting the Islamic Regime. The women’s agency, motivated by feminist demands, made them protesters in the vanguard for the first time in Iran’s history, and probably in the Muslim world. They believed women should have sovereignty over their clothing, their bodies, and their socialization with men, without the intervention of the state in the name of religion. In the Mahsa Movement, men came second; they backed women and showed their solidarity with them, but the impetus came from women.

On the other hand, men also wanted to free themselves from the constraints of the Theocratic Regime, create new relationships with women, mingle freely with them in broad daylight, and live with them without gender segregation. Male and female youth alike rejected the roles assigned to them by patriarchal Islam and openly engaged in the struggle for secular citizenship. One important difference with the earlier protest movements is that the Mahsa Movement directly challenged the Islamic Regime without any sense of guilt; on the contrary, as we shall see, the protesters had a clear conscience, they had no remorse in trampling the religious norms underfoot. This is the radical novelty of this movement: it seeks to innovate culturally and politically.

1The mindset of the younger generation: the new culture of “joie de vivre” against Islamic theocracy

Social movements are determined by objective, historical conditions but go beyond them. Activists launch the movement by questioning a social and political order they perceive as repressive and act to end their alienation and their sense of being dominated.1 In Iran, the main enemy is the Islamic Regime, which denies freedom to the people in the name of a theocratic version of Shi’ism. The Mahsa Movement was distinct from the large movements of 2009 (the Green Movement) and those of 2016–19. It differed from the former in that it unambiguously rejected the powers that be (the leitmotiv of the movement was “Death to the dictator” [marg bar dictator]), whereas the Green Movement of 2009 accepted the Islamic Republic and aimed at reforming it from within. It also differed from the latter in that the Mahsa Movement proposed a political system under the slogan “Woman, life, freedom.” Like the 2016–19 movements it was marked by a lack of leadership and organization, indicative of its institutional weakness. By cutting off the internet and massively arresting the demonstrators (around 20,000 arrests until end of January 2023), the Islamic Regime stifled the movement, which cruelly lacked organization and leadership, due to the government’s repression.

The objective causes of the Mahsa Movement were the increasingly totalitarian character of the political system coupled with the economic decline of the middle and lower classes and the elimination of Reformists (Khatami’s presidency from 1997 to 2005 was the apogee of reformism and since then, Reformists have been gradually excluded from the political arena). Iran was experiencing an increase in poverty as a result of the lack of development, government policies, and the duality within the Iranian State (the large organizations under the aegis of the Supreme Leader versus the official government). Furthermore, it was isolated on the international scene, and the withdrawal of the United States under President Trump from the nuclear treaty in 2018 and the application of restrictive clauses made the legal sale of oil extremely difficult for Iran, inducing the depreciation of the Iranian currency and a very high rate of inflation. The middle classes were feeling the effects of impoverishment too.

The subjective rationale for the movement was a youth that was not intimidated by government repression, unlike the older generations.

In the denial of the legitimacy of the Islamic Republic by the protesters, one dimension stood out: the secularization of the youth and the importance of this-worldly life, or what I will call “joie de vivre,” with all its pleasures including the unfettered relationship between men and women and full rights and freedoms for women. The extent of the youth’s secularization caught the Shi’i theocracy unawares. Foremost, they aspired to a secular life and repudiated mandatory religious values. They rejected the Shi’i theocracy as a killjoy2 and an agent of social injustice and poverty.3

In a sense, the Theocratic Regime has made the lives of young men and women alike unbearable for almost identical reasons: the denial of their subjectivity, of their sense of dignity, of their desire to be full-fledged citizens, of their wish to live in a less religious, more secular society, where each person can decide on their own faith, free from a normative religion imposed from above. In addition to the denial of freedom, high rates of inflation have pushed more than half of the population into poverty, including the middle classes.4

The dark view of the future is expressed by the Iranian rapper Emad Ghavidel in his song “My Generation” (nasle man), who has recently been put in prison:

Today I regret yesterday

Tomorrow I cry for today

I can’t sing with feelings anymore,

I’m from the burnt generation, let me wallow in the ashes.

The feeling of impotence is heightened by a dark despair that the singer eloquently expresses:

When as a young person, your joy of living (zowgh) is dead, continuing to live makes you nauseous.

It is with this deep sense of a future blocked and the present worse than the past that the movement of general insubordination began in September 2022 – not only as a protest, but also a way to recover the joy of life from the grasp of a killjoy state that epitomizes a combination of cultural oppression, economic injustice, political repression, and government corruption.5 The new generations are in touch with the outside world through the web and the Iranian diaspora (more than 3 million Iranians live outside Iran). They are aware of what is happening in their country in comparison to the outside world. The conjunction of repression, corruption, and negligence is unacceptable to them. On top of that, the government’s antagonistic attitude to the West hurts the new generations in terms of global economic development and, furthermore, does not reflect their views. It makes the Iranians’ social and material life difficult. They do not harbor adverse feelings towards the West, where a few million diasporic Iranians reside and mostly enjoy a middle-class standard of living. The Iranian youth dream of emigrating to the West, for lack of opportunity in Iran, but also to breathe the air of freedom alongside economic progress. One of the slogans of the Mahsa Movement protesters was: “Our enemy is here [the Islamic Republic]/They [the Islamic Regime proponents] lie by claiming it is America” (dochmane ma haminjast/dorouq migan amrikast).

A large part of Iranian youth in the 2020s is secular.6 Above all, often inspired by the Iranian diaspora who have managed to keep close ties with Iranians at home, they aspire to a pluralistic society where freedom of dress goes hand in hand with political freedom, in a peaceful relationship with the West.

The false piety of the parents and the provocative sincerity of their children

The rupture between private and public life, the growing chasm between the rich and the poor, the lack of basic freedoms to access leisure activities, and nepotism and lack of meritocracy are causes of frustration and humiliation among young people and they feel no respect for mandatory Islamic standards. Under the Pahlavis, the Iranian middle classes internalized many secular values.7

On the eve of the Islamic Revolution in 1979, almost half a century after Reza Shah’s secularization of the state in the 1930s, a large proportion of Iranian middle-class families had adopted secular mores. They were averse to mandatory religious prohibitions, but they naively believed that the so-called “Islamic Republic” would not be a hardline theocracy but a softened religious government.

More than four decades later, despite the Shi’i theocracy’s attempts to Islamize society, young, ordinary people, and even the children of the ruling elite, expressed their opposition through the Mahsa Movement. In everyday life, young people behave in a secular manner in public and reject the dualistic behavior of their parents, who pretend to be pious Muslims in the street while they behave in quite opposite ways at home. What their parents experience as double-dealing with the government, they experience as hypocrisy at best and schizoid at worst, and, in either case, as demeaning.

Through the Mahsa Movement, young protesters rejected duplicity and hypocritical Islamic behavior in public, asserting the dignity of the citizens over a coerced religiosity imposed from above by the government.

The older generations have begrudgingly accepted the harsh reality of a disingenuous society and the disconnect between private and public life under government repression. Within families, including those of the lower middle classes and working classes, a huge gap exists between their attitude in private and in public regarding Islamic prohibitions. Besides the pious, conservative Muslim families (probably a minority of 10–15 percent of the population), fathers consume, at least occasionally, alcohol (rich people drink whiskey, the poor, low quality brandy, araq), they do not perform daily prayers, and young people especially watch the forbidden channels through satellite dishes and mentally exile themselves from a gloomy daily life by consuming drugs or by adhering to new religions (Evangelism in Iran is thriving in spite of harsh repression). In the street, they are compelled to pretend to be decent Muslims. The list of restrictions is extensive: no breaking of the Ramadan fast, no woman without a veil, no consumption of alcoholic beverages, no sign of collective joy, no mixing of men and women, no outward sign of bodily contact (kissing, hugging), and so on. On top of that, young women must, often in the stifling heat of hot summers, be tightly covered. They feel more intensely than men the injustice of a system that their subjectivity rejects, which seems senseless. Subjectivity among the youth clashes with the simulacrum of Islamic behavior among their parents; it constantly challenges religious standards that young people dismiss as alien to their worldview. The Islamic Republic has become the epitome of an arbitrary and unjustifiable domination, at odds with the youth, estranged from their emotions. The heavier the ban, the more unquenchable the thirst for forbidden pleasures among young people; they feel an unending desire for transgression, on top of their urge to behave according to their secular mindset. Unlike their parents who play the double game with little or no contrition, the youth feel it is a humiliation to pretend to be what they are not, to live an insincere life of duplicity, epitomizing an unbearable submission to an illegitimate authority. Where the parents keep up the appearances of Islamic behavior in the street, the young people, driven by a new spirit, seek to accentuate their rupture with the Regime by taking their revolt to its limits, adding provocation to the desire to be oneself in a secular manner.

The older generations, the fathers and grandfathers, because duplicity, or hypocrisy, as far as the State is concerned is a fact of life, are not deeply affected by the dichotomy between the public and the private spheres. They are more willing to play cat-and-mouse with the government than the youth are. They also believe in this way that they are duping the Islamic State and that their make-believe is some sort of revenge on its strictures. But unlike their parents, young people feel it is demeaning to play this duplicitous game with the Regime. For them, it represents an unjustifiable denial of recognition by the Islamic State and they think it is an undeniable right to be outside without a veil, in the case of young women, or for a young man to go out with his hair greased back and chest bare. Imposed duality is repugnant to them and they experience it as a humiliation.

The cultural difference with their parents is immense. They want to be accepted for who they are, not who the powers that be demand. They sense in this duality in public life an attack on their dignity and a perverse game through which the Islamic State tries to stifle them individually before oppressing them socially. They denounce the religious restrictions imposed by the Islamic regime as a denial of their existential freedom to dispose of their bodies and their social relations. To refuse theocratic Islam is to reject repression and a state which is the very antithesis of their vision not only of politics, but of life itself. In that respect they are profoundly different from their parents and grandparents, whose self-esteem is not as affected by the diktats of the Theocratic State concerning Islamic posturing in the public sphere. The cat-and-mouse game goes against their feeling of authenticity, whereas for their parents it is a nasty game that they play spontaneously, without a feeling of alienation. For their children, playing this game is total alienation.

It is no coincidence that the Mahsa Movement, whose leitmotif was the “joie de vivre,” mobilized young people, but not the older generations. They live in two different worlds and communication between them is awkward.

What distinguished the revolt of the youth is that, on the one hand, they were not as fearful as their parents: they had not experienced the repression their parents had during the movements of 2016–19, in which they were too young to have taken part. But there is another reason: this government does not promise its young citizens a credible future. The Chinese government denies its citizens political freedom, but not the innocent joy of living (existential freedom they can moderately enjoy privately and in public, be what they are individually). Above all, it promises them an economic future that is brighter than the present, and this seems credible to many young people. But this is not the case in Iran where the Islamic Regime, at war with the West, prepares a future bleaker than the present, which is already darker than the past, as Iranian musicians remind us in their songs.

The new generations and the dismissal of the “Islamic patriarchal pact”

In Iran, from the 1930s under the Pahlavi monarchy up to 1979 when it was overthrown by a revolution spearheaded by Ayatollah Khomeini, women enjoyed a new legal status that was significantly superior to the Islamic tradition that prevailed before. Reza Shah’s Iran followed in the footsteps of Atatürk’s Turkey by involving women in the authoritarian modernization process from above. It forcibly removed their veil in 1936. Subsequently, after many decades, a large part of women in urban areas had internalized the unveiled identity and took off the veil, not anymore under constraint but by their own consent.

During the great demonstrations of the 1979 Revolution against the Shah, many modernized women temporarily wore headscarves to express their rejection of Mohammad Reza Shah’s authoritarian regime, as a sign of unity with the revolutionary movement, which they, like the men, saw as bringing freedom and social justice and not Islamic restrictions.

After the 1979 Revolution, the regression of women’s judicial status began in Tehran with a return to Islamic laws that denied women many rights and imposed the compulsory veil. Only two demonstrations by a few thousand women in protest against it took place, but they were not followed up, and the Islamic government applied the mandatory veil policy a few weeks after the Revolution, even before it was legally promulgated, denying unveiled women access to work in the public sector and then, forbidding women to appear without a veil in public.

This radical change was possible because many modernized and unveiled women lacked leadership and organization. In addition, left-wing female intellectuals like Homa Nategh believed that the veil had to be sacrificed to the petty-bourgeois revolution of 1979, which would be followed by a communist revolution in which women would regain their rights on an equal footing with men.

The modernized middle classes were devoid of organization because the Shah’s authoritarianism had decapitated all political parties and organizations, and few men, while accustomed to unveiled women in private and in public, reacted against the compulsory veil. The only way of protesting was to leave the country (several hundred thousand – estimated between 3 and 5 million – Iranians left Iran and settled in the USA, Canada, Australia, Europe, and Turkey).

Revolutionary effervescence in turn contributed to this: everything seemed unassailable under the charismatic leadership of Ayatollah Khomeini, who was a saint, a prodigy, a wizard (he had achieved the impossible, by dethroning the Shah). For a large part of the population, his position was regarded as sacrosanct and could not be called into question, on pain of betraying the revolutionary ideal of a total rebirth of society under his aegis. Even some secular men who might have doubted the validity of his words seemed to believe in his thaumaturgic ability to put an end to social ills. His stance was attributed to his sacred sagacity. Had it not been for the revolutionary effervescence of a seething society, he would have met with far more resistance than the scattered demonstrations of a few thousand women in Tehran. After all, unveiled women had been actively present in the public arena for almost half a century.

An Islamic patriarchal pact was implicitly struck between the Theocratic Regime and a large part of the society, notably the clergy, the traditional bazaaris (the Iranian merchant class), the fundamentalists, the lower middle classes from small towns, and particularly the so-called “oppressed” (mostaz’afeen), the poor people. They believed that Ayatollah Khomeini’s restoration of Islamic tradition would not only ensure their upward social mobility, but also, and above all, help them overcome the cultural traumas of authoritarian modernization under the Shah. In their eyes, the latter had destroyed tradition, without granting legitimacy to the new modernist culture. As for the modernized middle classes, while not supporting this patriarchal pact, they submitted to it because they had no organization to support them. The war launched by Iraq against Iran, which lasted over eight years (1980–8) and left several hundred thousand dead on both sides (over 500,000, including some 300,000 in Iran), made it difficult to protest against the religious constraints, because any effort in that direction was regarded as unpatriotic and the fight against the Iraqi enemy took precedence over all other considerations.

The patriarchal pact concluded with the Islamic State did not include the entire Iranian society. It was not, as in traditional societies, an all-encompassing social phenomenon with a deep-rooted cultural base, which would have imposed itself on society because patriarchy would have been the fundamental form of global identity.

I use the term “Islamic patriarchal pact” to distinguish my argument from that of Deniz Kandioty, who coined the term “Patriarchal bargain,”8 particularly in reference to traditional societies undergoing modernization, notably those in sub-Saharan Africa and the Middle East. Her study is about women’s strategies in the face of patriarchal attitudes rooted in culture: they suffer domination but also develop forms of resistance in the face of oppression. Her thesis is rooted in a global socio-cultural framework in which the state is, at best, an adjunct to the cultural norms that dominate and oppress women. In Iran, on the contrary, under the Islamic Regime, the patriarchal pact was drawn up between the Theocratic State and large groups of men after the overthrow of the Pahlavi regime. The Islamic Regime that took power in 1979 challenged the status of women and removed many of their rights established since the 1930s. It was the clergy, the traditional strata, the urban poor (the “oppressed”), and the fundamentalists (reacting against the Shah’s modernization) who forged an alliance with the Theocratic Regime to impose on women a subaltern status. Therefore, it was not a “traditional” patriarchy, but a resentful one, in reaction to the modernization of Iranian society for almost half a century, initiated by a theocratic state.

In short, the main force behind women’s institutional inferiorization through the implementation of Islamic laws was the Theocratic State headed by the charismatic Ayatollah Khomeini, rather than the patriarchal culture of society, which had undergone a fundamental change under the Pahlavi regime. The long war with Iraq and the lack of capacity for action on the part of the modernized strata made possible this edict that hit several million people head-on, many of whom chose to go into exile and live abroad. This scenario was repeated several times under the Islamic Regime, with waves of migrants swelling the ranks of those who had already left, whether after the Green Movement of 2009 and its repression, then the movements of 2016–19 and finally, in the wake of the Mahsa Movement of 2022.

Therefore, the Islamic patriarchal pact is different in nature from Deniz Kandioty’s patriarchal bargain: firstly, it is the state playing the essential role in the repression of women, and secondly, it was not Iran’s global social culture at its roots, but the domination of the Shi’ite clergy within a theocratic state in the wake of a revolution that left the modernized middle classes bereft of leadership, with no ability for collective action.

The Islamic patriarchal pact had initially been embraced by a large part of a society in revolutionary fervor, except for the modernized middle classes who were a disempowered minority and whose youth had in part embraced the revolutionary ideals of the Marxist far left. While the poor (the “oppressed,” mostaz’afeen) pushed for Islamization as a means of their empowerment, the modernized middle classes became a submissive social group which, while disagreeing with the religious fundamentalists, was unable to oppose them. With the help of his entourage and the revolutionary youth, Khomeini set up the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC), which later became the main repressive force against urban protest, along with Basij, a youth volunteer organization that was quickly brought under the aegis of the IRGC. The Islamic patriarchal pact was built in opposition to the secular culture of the modernized middle classes. Ayatollah Khomeini, backed by the clergy, was seeking revenge for the decades-long suppression of the veil (kashf hejab) under the Pahlavis. He imposed it at a time when a veil-free identity had become commonplace among modern middle-class women and a significant proportion of Iran’s female educated youth.

The paradox is that four decades later, the patriarchal pact was challenged by a new generation of women that included children of the new Islamic elites. Women gradually became aware of the impossible gender equality under Islamic rule. As for the young men, they also subscribed to this challenge. They rejected the Theocratic Regime’s religious mores, which were at odds with their youthful identity. They had evolved towards a secularization that was opposed to the worldview championed by the patriarchal pact. The latter had been emptied of its meaning and had lost legitimacy after more than four decades. At the start of the 1979 Revolution, the “oppressed” strata (mostaz’afeen) believed that the Islamic project was synonymous with the restoration of a mythologized tradition and their social and economic ascent. The economic regression of the bulk of society and the conscientization of increasingly educated women in the following decades resulted in a growing section of society questioning the patriarchal pact. As for the growing number of the “oppressed,” they no longer believed in the restoration of Islamic tradition, which would protect them from the woes of modernization, while ensuring their economic and social progress. With the Mahsa Movement, many decades after the 1979 Revolution, a large part of society was questioning the patriarchal pact against a theocratic state whose policies had shown that the so-called restoration of Islamic tradition was synonymous with social, economic, and cultural regression for the vast majority.

The patriarchal pact was particularly discredited by the new generation of women, because it confined them to an increasingly unbearable inferiority in a society that did not believe anymore in the bright Islamic future promised by the Revolution, and by young men, because in their eyes, religious tradition increasingly meant calling into question their culture of “joie de vivre” so alien to the morbid religiosity of the Islamic Regime. Men and women alike rejected head-on a state that was driving society backwards, while denying them the freedom of mores they cherished by virtue of their secularization.

The main driving force behind the Mahsa Movement has been Iran’s youth. According to the statistics of people arrested during the demonstrations, 80 percent of them were aged between fifteen and twenty-four, and 20 percent between twenty-five and forty-five. The share of those aged between fifteen and twenty-four years in the overall population of the country was about 13 percent, and those aged between twenty-five and forty-five, about 40 percent.9 Without doubt, the Mahsa Movement has been a youth movement (more than six times their proportion in the overall population of fifteen to twenty-four year olds were arrested). This does not mean that the older generation, known in Iran as the “grey-haired generation” (nasle khakestari), were against the movement. Quite the contrary, they supported its demands, but they did not actively participate in the street demonstrations, for various reasons (lack of an alternative government, fear of the repressive Islamic Republic, concern for the family, fear of embarking on a new revolution having seen how the old revolution ended in deadlock and created a situation worse than the Shah’s regime before).

The new youthful mindset presents a resourcefulness among women who are subject to far greater legal restrictions. The change in their mentality began in the 1980s in their attitude towards the number of children in the family. On the eve of the 1979 Revolution, women gave birth to seven children on average. Fertility dropped to two children in 2000. Over the next decade it dropped even further and in 2009 it reached 1.9 children.

The level of education of women rose continuously during those years. In 1976 only 8.7 percent of women had reached secondary school level, a figure which stood at 37.6 percent in 2016. In 1976 only 1.5 percent of women studied at university, whereas in 2016 nearly one-third of women (28.9 percent) attended university.10

It should be noted that the new female subjectivity appeared in Iran at the end of the twentieth century, especially with the expansion of education to women and their entry into university, where half of the students since the year 2000 are female. The universities, where more than 3 million students are enrolled, are the major breeding ground for this new awareness. The paradox is that the more women’s cultural status is brought closer to men’s through school, university, and the web, the more the Iranian Theocratic Regime hardens its stance towards them, especially under the populist President Ahmadinejad in 2005, and in 2021, the hardliner Raissi. Women have faced more extensive legal and social restrictions since then. Although they make up over 50 percent of university graduates, their participation in the workforce is only 15 percent according to the latest official statistical data.11 The 2016 Global Gender Gap report, produced by the World Economic Forum, ranked Iran in the bottom five countries (141 out of 145) for gender equality, including equality in economic participation (a 2017 report by the Iranian Center for Statistics indicates that women make up 18.2 percent of the workforce). Moreover, these disparities exist at all levels of the economic hierarchy: women are severely underrepresented in high-level public positions and in private sector leadership positions. This significant gap in participation in the Iranian labor market has occurred against a backdrop of widespread violations of women’s economic and social rights by the authorities. In 2012, under the presidency of Ahmadinejad, who fraudulently won the election by many accounts,12 at least seventy-seven faculties in thirty-six different universities refused female students. The last years of his administration also coincided with the government’s stated goal of population growth. During this period, several pieces of legislation were introduced in parliament that further marginalized women in the labor market.13

Many men in the new generations share the feeling of quasie-quality with women in everyday life, whether within the nuclear family or in social relations within the community. The Mahsa Movement has forged a tight alliance between young men and women against the Islamic Republic. They chanted in unison the slogan “Woman, life, freedom.”