2,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: tredition

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

This book is about Richard of Cornwall, an English earl and brother of the English king, who became King of the Germans in 1257 This historical tale tells his story. It takes the reader back to those turbulent times and into the life and deeds of Richard, "the wealthiest prince in Christendom", a man more inclined to resolve conflicts through negotiations than war.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 105

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

Christoph Werner

Richard of Cornwall

AN ENGLISHMAN ON THE GERMAN THRONE

Historical Tale

Editor Michael Leonard

© Christoph Werner 2022

German Edition:

Richard von Cornwall. Ein Engländer auf dem deutschen Thron. Historische Erzählung

Editor: Michael Leonard

Cover photo and layout: Helga Dreher

Published by tredition GmbH, Hamburg, Halenreie 40-44, 22359 Hamburg

ISBN

978-3-347-67370-0 (Paperback)

978-3-347-67375-5 (eBook)

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

Table of Contents

1. Youth

2. Quarrel with the king and reconciliation

3. Richard’s Crusade

4. Richard becomes King of Germany

5. The second voyage to Germany

6. The third voyage to Germany

7. German King or elected emperor held in captivity in England

8. Fourth journey to Germany and death in England

9. Personality and Impact

10. Other Facts of Interest

11. Bibliography

About the Author

Also by Christoph Werner

Books by Christoph Werner

1. YOUTH

These days, after the unfortunate event called Brexit, it seems a charming memory that once upon a time an Englishman was the king of the Germans, of the Holy Roman Empire. He wasn’t, however, quite an Englishman in the true sense of the word, rather an Anglo-Norman whose ancestors had come to England almost 200 years earlier. And Normandy, in northern France, is where the Normans or Norsemen or Vikings, after numerous raids at the beginning of the 10th century, had finally settled and become part of the kingdom of France in 911.

William, Duke of Normandy, later called the Conqueror, set out from Normandy, crossed the Channel and fought against Anglo-Saxon King Harold at the Battle of Hastings in 1066. Harold lost, was killed in that battle, which allowed William to make himself comfortable on the English throne. Not to do him an injustice, it must be added that he did not find a peaceful end. It is said, anecdotally, that when he laid siege to the castle of Mantes in France, setting it on fire, sparks flew in the air, causing William’s horse to step on a hot cinder and stumble. The Conqueror fell forward on to the point of his saddle and did himself a nasty injury, probably burst his bladder. He died in agony. But worse was to come. He was a strong man and rather fat, and because his body began to swell as it rotted, he was too big to fit in the stone tomb that had been prepared for him. As the body was forced in, it burst. The smell was so bad that the priests rushed through the funeral service and then bolted. Served him right, some of the Anglo-Saxons may have thought.

The military and political catastrophe of 1066 seemed to the people on the island to have been visited upon them by God because a comet, which had already announced the birth of Christ – today called Halley’s comet – had appeared some months before. All this is depicted on the Bayeux tapestry, a medieval embroidery, remarkable as a work of art and important as a source for 11th century history. It is a band of linen 70 meters long and 49.5 cm wide representing 70 scenes from the Conquest.

The Anglo-Saxons mentioned above had nothing to do with today’s Saxons around Dresden, who are quite gemütlich and little interested in conquest. Rather the Anglo-Saxons were descendants of three Germanic tribes, the Angles, the Saxons, and the Jutes, who lived in northern Germany and had come to England in the 5th century. This happened, so tradition has it, at the invitation of the Celtic-British warlord Vortigern, who wished for help defending his country against the Picts from Scotland and the Irish. But instead of returning to their homeland after having helped, as guests should do, they stayed in England, made war against the romanized Celts, whom they subjugated. Worse still, they founded seven kingdoms, among them Essex, Sussex and Wessex, that is East Saxony, South Saxony and West Saxony, to which were added East Anglia, Middle Anglia, Mercia and Northumbria, founded by the Angles, and lovely Kent, where the Jutes settled. All had brought their native tongues with them to England, where a language now known as Old English developed, which is quite similar to the German of that age.

Interestingly enough, although Romans, Vikings and Normans had all conquered England, and in very ancient times the Celts had settled there, the Anglo-Saxons left the clearest traces in the gene pool of the English white population. Today 30 percent of their DNA is shared with the Germans, though it does not seem to show.

Let us make a jump to the main character of our tale, Richard. He was born in Winchester on 5 January 1209, as the second son of King John. When he was six years old, he was taken to Corfe Castle, that was in 1215. Richard was not of German descent, but an offspring of William the Conqueror.

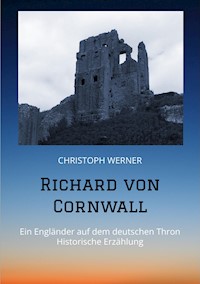

Corfe Castle is located in the village of the same name on the Isle of Purbeck, actually a peninsula, in the county of Dorset in the very south of England. Richard’s father, King John, whose father rather uncharitably had given him the nickname Lackland, i.e., without land, because he was not to inherit any larger estates, decided that his second son would be best housed at this awe-inspiring and safe castle.

Corfe Castle and many other castles in England after the Norman conquest were used as symbols of the new rule and at the same time as military bases, because the Anglo-Saxon population was not entirely happy with their new masters.

A French niece of King John, Eleanor, had been held captive in the castle together with twenty-two of her French knights. She escaped with her life while the knights were left to starve to death in the dungeon. Out of revenge, the ghosts of the dead haunted the castle and frightened the inhabitants when they, around midnight, dared to relieve themselves in the latrines, which were located in niches in the outer walls above drop shafts. Groans and desperate cries from the dungeon were no longer heard, however, when Richard was brought to the castle.

Little Richard was well watched over and performed his ablutions into a chamber pot, which was emptied and cleaned by his washerwoman. Moreover, he was of a cautious nature

and, if at all possible, preferred to stay in his warm bed.

Outside the castle walls it was especially dangerous, because in the woods around the castle there were wolves and bears, lynxes and wild boars, which were not peacefully minded. The young prince’s court consisted of his teacher, an overseer, two trumpeters and the washerwoman mentioned afore. What the trumpeters did throughout the day has not been handed down. It is to be hoped to the prince’s benefit that they did not perform their duties exclusively with blowing their trumpets. The washerwoman was probably English, Anglo-Saxon, to be precise, and while she washed the king’s son, watched over his health, and probably on other occasions she spoke English with him. This was in spite of the fact that the official language, the language of the Anglo-Norman nobility, the merchants, the administration, the judiciary, the royal court, and wealthy townsmen was Norman French. Of course, Richard’s tutor, Sir Roger d’Acastre, and his overseer, Peter de Mauley, spoke French with their pupil. Anglo-Saxon was the language of the simple folks and was held in low esteem by the Norman nobility, although some clever people gradually began to learn it, for, after all, orders had to be given and understood by the common people. Moreover, it was useful to hear the halfmuttered curses and insults of the servants and peasants and deal with them.

Corfe Castle, now in ruins, was then considered one of the strongest fortresses in England, practically impregnable. On the ramparts of the massive walls King John had various catapults and machines erected in order to receive unwelcome arrivals by throwing stones and flammable materials at them. In 1212, the king stored a large part of his treasure, 200,000 marks, in the castle.

John was a cruel king, who, for example, imprisoned the soothsayer Peter de Pomfret, probably mentally disturbed, and his son in the castle and finally had them killed. The selfproclaimed prophet Peter had predicted the end of the king’s reign, which no ruler likes to hear. He was put to death by having him tied to horses, dragged around the castle and, barely alive, hanged.

Long before King John and before the Norman Conquest in 1066, the old castle had already been the scene of a crime. When the Saxon King Edgar suddenly died at the age of 31 in 975, the followers of his two sons Edward and Aethelred quarreled over his succession. The older, Edward, became king despite the resistance of his stepmother Aelfthryth (Elfrida), Edgar’s second wife. She understandably wanted to make her son Aethelred king. On March 18, 978, the seventeen-year-old King Edward returned from a hunting excursion to the village of Corfe Castle where his stepbrother and stepmother lived. When he had mounted his horse again after his visit and was about to ride away, one of Elfrida’s treacherous servants seized his left hand, held it fast and stabbed the king with a knife. On his other side, a second man tried to drag him from his horse. The king spurred his horse in order to escape the attack, but fell from the saddle, got stuck with one foot in the stirrup and was thus dragged to the castle gate, where he was found dead.

Another tradition says that he fell from his horse and was stabbed in the stomach, so that his bowels fell out and he died on the spot.

Now things happened that can only be called most sacred. A blind woman, in whose house Edward’s dead body had lain, woke up at midnight and found her house brightly lit by a miracle and, another miracle, regained her eyesight. A year after his murder a pillar of fire appeared over his hidden tomb. After the residents had dug up his body, a spring of healing water arose there, which was said to be particularly useful for curing blind people. Edward was declared a martyr and canonized in 1008. His intercession is most often sought against glandular diseases. Whether it helps is not proven. However, according to the saint’s followers, it is at least not harmful.

These spooky stories later reinforced Richard’s basic peaceful attitude, which made him prefer negotiation rather than waging war. They could have, of course, had the opposite effect, as can be read in the descriptions of the lives of other people who use the fears of their childhood to torment others. After an uprising of the barons, his father, King John, had, no doubt grudgingly, to sign Magna Carta in 1215, which contains the famous and momentous article that

no free man is to be arrested, or imprisoned, or disseised, or outlawed, or exiled, or in any other way ruined, nor will we go against him or send against him, except by the lawful judgment of his peers or by the law of the land.

The enmity of the barons, i.e., the landowning nobility, went far. They were actually the vassals of the king, who granted them their fiefs, that is their piece of property, usually land, in return for service, which normally included military duties. The fief holder swore fidelity to the person from whom the fief was held and became his man. Despite that the barons turned against the king when he demanded, among other things, new taxes, which they regarded as too high.

They offered the English crown to the French king’s son Louis. Now this was a veritable case of high treason against their own country. But the barons, who still had fairly close ties with Normandy and France, saw things differently. Louis, later King Louis VIII of France, was married to the granddaughter of Henry II of England, Blanca of Castile, and thus could pretend to have a claim to the English throne. The barons’ offer suited him just fine. He landed in England in May 1216 and captured London, where he was proclaimed king though without being properly crowned.

The alliance between the rebels and the French succeeded in conquering large parts of England. King John attempted to defend his kingship with varying success, among which is the loss of the English crown jewels with much of his baggage train