Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Old Pond Books

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

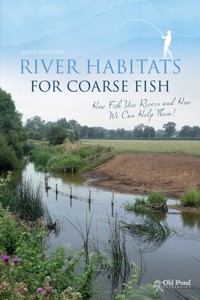

This illustrated guide describes the many ways that coarse fish species depend upon the diversity of habitats in river systems and considers how this dependence changes throughout the stages of their lives - from spawning and eggs, through to the juvenile and adult stages- and with changing seasons and river conditions. This knowledge is important if we are to understand the many population bottlenecks and the variety of coarse fish species that have resulted from historic changes to our rivers. It is also important if we are to manage rivers positively to protect and improve the vitality of coarse fisheries - a process that will also benefit the wider wildlife community with which coarse fish are interdependent.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 102

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

River Habitats for Coarse Fish

How Fish Use Rivers and How We Can Help Them

Mark Everard

Contents

River Habitats for Coarse Fish: An Introduction

A FAIR AMOUNT OF guidance has been produced over the years on habitat management for salmon and trout fisheries. Look no further than the Wild Trout Trust’s excellent Wild Trout Survival Guide as an exemplar. Yet coarse fish in rivers remain something of an ugly duckling. This is despite the fact that many more people fish and live near rivers that support predominantly coarse fish populations. Furthermore, coarse fish populations are every bit the indicators of rivers in good health that salmonid species are generally acknowledged to be.

Healthy and balanced coarse fish populations are also just as much threatened as their silver and spotted brethren. Whether we look at pollution, over-abstraction, habitat loss, invasive alien species, excessive predation or a host of other pressures, coarse fish stocks are vulnerable to all we throw at them in the name of (often unsympathetic) development.

All of these wider pressures can be significant, and require attention. But such is the impoverished, pressurised nature of contemporary landscapes that a paucity of necessary habitat can often constrain river ecosystems, including their fish populations. Habitat improvement can also go some way towards compensating for some of the broader problems that arise from low flows and some forms of pollution, and can offer refuges from increasing levels of predation in river systems. Furthermore, habitat is something that we can all do something about, whilst often the best we can accomplish in addressing the other major pressures on our river systems is to support campaigns by regulators and larger voluntary organisations.

This guide focuses primarily on the role of habitat in sustaining the life cycles of fish and supporting river health. From this initial overview, the guide then turns to practical measures that concerned anglers and angling organisations, fishery owners and rivers trusts, conservationists and conservation bodies, and the wider public can do to protect or improve river habitats for coarse fish.

This is because fish matter. You really don’t need to be a keen angler or a fish biologist to appreciate these often overlooked but iconic players in river ecosystems. This is because some fish species have direct conservation value, but is also because all fish species play important roles in the delicate balance of nature. This includes serving as prey for herons, kingfishers, otters and other, perhaps more charismatic (at least in the eyes of many of the general public), species within river ecosystems. Thriving fisheries also speak of healthy water, which is cheaper to treat on its way to our taps and safer to paddle and swim in, and of diverse ecotourism and other benefits to fishers and non-fishers like. So, when fish are absent, we all know instinctively that something is wrong.

This short pictorial guide is thus a long time overdue, and also constitutes a manifesto of the importance of river habitats for coarse fish and the wide benefits they convey to society. I hope it is picked up and used by as many people as possible. Members of the UK’s Angling Trust and the rivers trust movement, as well as wildlife trusts, fishing clubs and other fishery interests, constitute obvious reader groups, as do regulators and the owners of riverbanks. But I hope that many more people will realise that they are already more empowered than they had previously thought, and that by becoming a little more informed they will be emboldened to take into their own hands the rehabilitation of the precious yet vulnerable resource that is rivers and their coarse fish populations.

How Coarse Fish Use River Habitats

TO UNDERSTAND HOW coarse fish use habitats, it is necessary first to think about the driving forces of their behaviour. In simple terms, this boils down to three principal variables, which I define in my 2006 book The Complete Book of the Roach as ‘the three Fs’. These are feeding, flight and reproduction. (If you don’t understand the last one, ask a friend, but the word ‘fecundity’ serves well enough!) Throughout this guide, I will return to how these three principal variables influence the way fish use habitats throughout their lives.

Life cycles of British freshwater fishes

All species of British freshwater fish are egg-layers, though this is by no means true of all of the world’s fishes, as some families release free-swimming young. The time of year at which Britain’s freshwater fishes lay their eggs, their general spawning strategy, and the nursery and refuge needs of juveniles vary between species and families. The three Fs are a useful framework within which to consider how important the diversity of river habitats is in enabling the varied fish fauna of rivers to complete their life cycles and to thrive as part of healthy river ecosystems.

Spawning substrates can range from flushed gravels, generally in shallow water and entailing upstream migration, to submerged aquatic vegetation, which can include soft vegetation or tree roots, and hard submerged surfaces, such as rocks and tree boughs.

The large majority of British freshwater fishes exhibit no brood care once the eggs are laid, relying on a high fecundity strategy to enable a sufficient number of individuals to survive to reproductive age. Significant exceptions here are the males of both British freshwater species of stickleback – the three-spined stickleback (Gasterosteus aculeatus) and the nine- or ten-spined stickleback (Pungitius pungitius) – which build nests out of pieces of soft vegetation into which they attract mates to lay their eggs, the male fish then demonstrating brood care until the fry are free swimming and able to disperse to fend for themselves. Another example is the bullhead (Cottus gobio), a highly territorial species that may live their whole lives under the same rock. The male bullheads attract adjacent females to lay their eggs on the ceilings of their rock caves, drive the females off, then care for the eggs and fry until they are free swimming and able to disperse to claim their own home territories.

For all British coarse and game fishes, the first free-living life stage, once hatched from the egg, is known as the alevin. Alevins, also known as ‘free embryos’ as they are only partially metamorphosed, are characterised by still being connected to a yolk sac, which they consume over a matter of days. Once the yolk has been consumed, the juvenile fish become free swimming, at which point they are known as fry. Fry undergo a range of different developmental phases, including the separation and development of the fins and coloration. They grow progressively on a diet of small aquatic organisms, generally algae and microscopic invertebrates such as rotifers to begin with, before progressing through a sequence of larger invertebrates. The point at which the fry stage ends is largely arbitrary, and the fish continues to grow beyond the fry stage and throughout their adult lives. During the transition from alevin to adult, the fish may exploit a range of habitats within river and lake systems to support their evolving needs.

Life cycles of roach and barbel, as typical of many vegetation and gravel-spawning coarse fish species, showing seasonal cycles and indicative sizes (drawings not to scale)

A nursery habitat is vital for the safety, growth and diet of free-swimming juvenile fish. Refuge from strong currents adjacent to the spawning habitat, into which the tiny fish may otherwise drift, is essential, as the fry of most coarse species at this stage are smaller than a human eyelash. Due to their diminutive proportions, but also because the fins and body musculature are only partially developed, smaller fry are unable to swim actively against even the most modest of currents. Shallow, well-vegetated marginal habitats also warm quickly in the summer, supporting a diversity of suitable food and providing refuge from predators. Warming is particularly important for the growth and survival of juveniles. Following a cool summer, the young of species such as chub (Leuciscus cephalus) may not grow sufficiently in size and strength to withstand autumn and winter spates. Whole year classes, experienced by anglers generally as fish within specific size ranges, may consequently be missing from river populations.

Major exceptions to this generalised life cycle include the European eel (Anguilla anguilla), which undertakes a reverse migration to sea to spawn in an amazing life cycle that is assumed (but is yet to be proven) to include migration back to the Sargasso Sea, from where the developing larvae, or leptocephali, are known to drift back on ocean currents to repopulate European waters. Some estuarine fish species – including three species of mullet (Chelon labrosus, Liza ramada and Liza aurata), the European seabass (Dicentrarchus labrax), the flounder (Platichthys flesus) and the sand smelt (Atherina presbyter) – spawn in coastal waters, though estuaries are important nursery areas, whereas the European smelt (Osmerus eperlanus, distinct from the sand smelt) spawns in estuaries, which are important habitats for all of its life stages.

For more detail on the life cycles of Britain’s freshwater fishes, see my book Britain’s Freshwater Fishes.

Fish migration

Before considering in more detail how coarse fish use river habitats to complete their life cycles, it is first important to address a common misnomer: that salmonid species (members of the family Salmonidae) migrate but coarse fish species do not. In fact, virtually all coarse fish species migrate, and it is only rare exceptions, such as bullheads, stone loach (Barbatula barbatula) and spined loach (Cobitis taenia), that do not. Note that this does not just include longer-distance migrations, such as those often associated with the running of rivers to find a favourable spawning habitat.

In many stretches of river, coarse fish can migrate significant distances along the river channel. For example, on a number of occasions I have caught the same large roach (Rutilus rutilus), characterised by particular scars and other distinguishing features, from swims a mile apart on consecutive days. Radio-tracking experiments on dace (Leuciscus leuciscus) and pike (Esox lucius) reveal significant movement both on a daily cycle and between days. (For a more detailed overview of the dace life cycle and migration, see my book Dace: The Prince of the Stream; for aspects of the barbel (Barbus barbus) life cycle and seasonal migrations, see Barbel River). Consequently, a suitable habitat that is accessible along the river channel is extremely important.

Although salmonids are generally considered migratory fishes, coarse fish also migrate along and across river channels. Dace (top) in particular can undertake prodigious migrations, for which their body form, similar to that of a trout (bottom), is ideally suited

Fish migrate along stretches of river (yellow arrow), and into margins and adjacent streams, ditches and wetlands (amber arrows), according to season, life stage, time of day/night, weather and flow conditions

Fish also migrate laterally, both into the margins of rivers and into tributaries, ditches, drains and connected wetlands. These lateral connections are in fact hugely important for nursery and refuge purposes.

Significant lateral migrations can occur seasonally or according to the different life stages, as well as on a daily cycle or in response to changing weather, predation pressure or even pollution events. Consequently, where this marginal habitat is impoverished, the capacity of fish to respond to circumstances, and sometimes even to complete their life cycles, may be seriously compromised.

Spawning habitats

There is a wide diversity of life cycles amongst the various species of fish encountered in our rivers. Spawning behaviour is particularly diverse; for example, some fish species (mainly salmon and trout) spawn in the winter, others spawn at the very first hint of spring, and many more wait until the rising temperatures of late spring and early summer.

The diversity is also reflected in the broad range of habitats in and upon which the fish spawn. It is thus clearly essential that your stretch of river has a sufficiently diverse range of habitats to adequately meet the spawning habitat requirements of all desirable species.