10,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

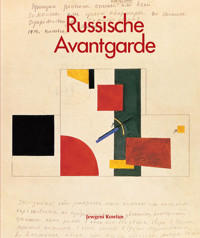

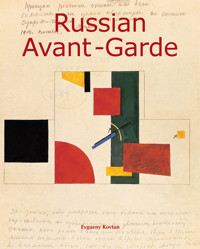

- Herausgeber: Parkstone International

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

The Russian Avant-garde was born at the turn of the 20th century in pre-revolutionary Russia. The intellectual and cultural turmoil had then reached a peak and provided fertile soil for the formation of the movement. For many artists influenced by European art, the movement represented a way of liberating themselves from the social and aesthetic constraints of the past. It was these Avant-garde artists who, through their immense creativity, gave birth to abstract art, thereby elevating Russian culture to a modern level. Such painters as Kandinsky, Malevich, Goncharova, Larionov, and Tatlin, to name but a few, had a definitive impact on 20th-century art.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 151

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

Text: Evgueny Kovtun

Translation: Nick Cowling and Marie-Noëllle Dumaz

Layout:

Baseline Co. Ltd

61A-63A Vo Van Tan Street

4th Floor

District 3, Ho Chi Minh City Vietnam

© Parkstone Press International, New York, USA

© Confidential Concepts, Worldwide, USA

Art © Nathan Altman/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

© Hans Arp Estate, Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, USA/ ADAGP, Paris

© Marc Chagall Estate, Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, USA/ ADAGP, Paris

Art © Alexander Deineka/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

Art © Robert Falk/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

© Natalia Goncharova Estate, Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, USA/ ADAGP, Paris

© Wassily Kandinsky Estate, Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, USA/ ADAGP, Paris

© Pyotr Konchalovsky Estate, Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, USA/ ADAGP, Paris

© Vladimir Kozlinsky Estate, Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, USA/ ADAGP, Paris

© Mikhail Larionov Estate, Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, USA/ ADAGP, Paris

Art © Vladimir Lebedev Estate/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

© Lasar Markowitsch Lissitzky Estate, Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, USA/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

© Ivan Puni Estate, Artists Rights Society, New York, USA/ ADAGP, Paris

Art © Alexander Rodchenko Estate/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

© Martiros Saryan, Estate, Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, USA/ ADAGP, Paris

© Nikolai Suetin Estate, Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, USA/ ADAGP, Paris

© Vladimir Tatlin Estate, Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, USA/ ADAGP, Paris

© Yuri Annenkov

© Sergei Bulakovski

© David Burliuk

© Maria Ender

© Vera Ermolaeva

© Evguenija Evenbach

© Alexandra Exter

© Pavel Filonov

© Elena Guro

© Valentin Kurdov

© Nikolai Lapshin

© Aristarkh Lentulov

© Ilya Mashkov

© Mikhail Matiushin

© Alexander Matveïev

© Kuzma Petrov-Vodkine

© Bossilka Radonitch

© Alexandra Schekatikhina-Potoskaya

© Alexander Shevchenko

© Lyubov Silitch

© Pyotr Sokolov

© Sergei Tschechonin

© Lev Yudin

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced or adapted without the permission of the copyright holder, throughout the world. Unless otherwise specified, copyright on the works reproduced lies with the respective photographers. Despite intensive research, it has not always been possible to establish copyright ownership. Where this is the case, we would appreciate notification.

ISBN: 978-1-78310-381-2

Evgueny Kovtun

Contents

I. Art in the First Years of the Revolution

‘Picasso, this is not the new art.’

The Spiritual Universe

The ROSTA Windows (Russian Telegraph Agency) of Petrograd

The Sevodnia Artel

The VKhUTEMAS [Higher Art and Technical Studios]

Wassily Kandinsky

The Struggle Against Gravity

The ‘Renaissance’ of Vitebsk

II. Schools and Movements

The Institute of Artistic Culture

The Additional Element

Elena Guro

The Signal for a Return to Nature

The End of the INKhUK

Malevich’s Second Peasant Cycle

The Rebellion Against God

The National ‘Tone’ of Colour

Filonov and the Masters of Analytical Art

The Kalevala

Artistic Groups in the 1920s

Sculpture, Porcelain and Textile Manufacture

The Avant-Garde Stopped in its Tracks

MAJOR ARTISTS

The Association of Artists of Revolutionary Russia(AKhRR),(renamed in 1928The Association of Artists of the Revolution- AKhRR),1922-1932, Moscow - Leningrad

Circle of Artists, 1925-1932, Leningrad

The Masters of Analytical Art(MAI), 1925-1932, Leningrad

The Makovets, 1921-1925, Moscow

The World of Art, 1898-1904, 1910-1924, St Petersburg - Moscow

Monolith, 1918-1922, Moscow

The New Society of Painters(NOZh), 1921-1914, Moscow

Oktiabr(including the group Molodoi Oktiabr), 1930-1932, Moscow — Leningrad

Painters of Moscow, 1924-1926, Moscow

The Four Arts Society of Artists, 1925-1932, Leningrad — Moscow

The Society of Moscow Artists(OMKh), 1927-1932, Moscow

The Union of Youth, 1910-1914, 1917-1919, St Petersburg — Petrograd

Nathan Altman (Vinnitsa, 1889 - Leningrad, 1970)

Yuri Annenkov (Petropavlovsk-Kamchatski, 1889 - Paris, 1974)

Sergei Bulakovski (Odessa, 1880 - Kratovo, 1937)

Leon Bakst (Grodno, 1866 - Paris, 1924)

David Burliuk (Hamlet of Semirotovchtchina (now region of Kharkov), 1882 - Long Island, New York, 1967)

Marc Chagall (Vitebsk, 1887 - Saint-Paul-de-Vence, 1985)

Alexander Shevchenko (Kharkov, 1883 - Moscow, 1948)

Yuri Schukin (Voronej, 1904 - Moscow, 1935)

Maria Ender (St Petersburg, 1897 - Leningrad, 1942)

Vera Ermolaeva (Petrovsk, 1893 - district of Karaganda, victim of Stalinist repression, 1938)

Evguenija Evenbach (Krementchug, 1889 - Leningrad, 1981)

Alexandra Exter (Belostok, 1882 - Fontenay-aux-Roses, 1949)

Robert Rafailovich Falk (Moscow, 1886 - Moscow, 1958)

Pavel Filonov (Moscow, 1883 - Leningrad, 1941)

Natalia Goncharova (Negayevo, 1881 - Paris, 1962)

Elena Guro (St Petersburg, 1877 - Uusikirkko, 1913)

Lev Yudin (Vitebsk, 1903 - Leningrad, died on the front near Leningrad, 1941)

Pyotr Kontchalovsky (Slaviansk, 1876 - Moscow, 1956)

Wassily Kandinsky (Moscow, 1866 - Neuilly-sur-Seine, 1944)

Valentin Kurdov (Mikhailovskoie, 1905 - Leningrad, 1989)

Mikhail Larionov (Tiraspol, 1881 - Fontenay-aux-Roses, 1964)

Vladimir Lebedev (St Petersburg, 1891 - Leningrad, 1967)

Aristarkh Lentulov (Vorona, 1882 - Moscow, 1943)

Lazar Lissitzky, known as El-Lissitzky (Potchinok, 1890 - Moscow, 1941)

Ilya Mashkov (Hamlet of Mikhailovskaya, now district of Ourioupinsk, region of Volgograd, 1881 - Moscow, 1944)

Kazimir Malevich (Kiev, 1878 - Leningrad, 1935)

Mikhail Matiushin (Nijni-Novgorod, 1861 - Leningrad, 1934)

Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin (Khvalynsk, 1878 - Leningrad, 1939)

Alexander Rodchenko (St Petersburg, 1891 - Moscow, 1956)

Mikhail Sokolov (Yarloslavl, 1885 - Moscow, 1947)

Nikolai Suetin (Miatlevskaya, 1897 - Leningrad, 1954)

Vladimir Tatlin (Moscow, 1885 - Moscow, 1953)

Bibliography

Index

Notes

Kazimir Malevich, Red Square, 1915.

Oil on canvas, 53 x 53 cm.

The State Russian Museum, St Petersburg.

I. Art in the First Years of the Revolution

‘Picasso, this is not the new art.’

At the beginning of the twentieth century Russian art found itself at the cutting edge of the world’s artistic process. The decades dedicated to the renewal of pictorial art in France were condensed into approximately fifteen years in Russia. The 1910s were marked by the growing influence of Cubism, which in turn modified the ‘profile’ of figurative art itself. But around 1913, the break up could already be felt, with new visual issues emerging and the scales tipping toward the Russian Avant-Garde. In March 1914, Pavel Filonov declared that ‘the centre of gravity of art’ has been transferred to Russia[1]. In 1912, Filonov criticised Picasso and Cubo-futurism, saying that it ‘leads to an impasse by its principles.’[2] This statement came at a time when this movement was triumphing in Russian exhibitions. The most sensitive Russian thinkers and painters saw in Cubism and in the creations of Picasso not so much the beginning of a new art but the outcome of the ancient line of which Ingres was the origin.

Nicholas Berdiaev: ‘Picasso, this is not the new art. It is the conclusion of a bygone art.’ [3] Mikhail Matiushin: ‘Thus, Picasso, decomposing reality through the new method of Futurist fragmentation, follows the old photographic process of drawing from nature, only indicating the scheme of the movement of planes.’[4] Mikhail Le Dantyu: ‘It is profoundly incorrect to consider Picasso as a beginning. He is perhaps more of a conclusion, one would be wrong to follow this path.’ [5] Nikolai Punin: ‘One cannot see in Picasso that it is the dawning of a new era.’ [6] The French Cubists have stopped at the threshold of non-figuration. Their theorists wrote in 1912: ‘Nevertheless, let’s confess that the reminiscence of natural forms cannot be absolutely disowned, at least not for the moment.’ [7] This Rubicon was then resolutely transgressed by Russian art in the work of Wassily Kandinsky and Mikhail Larionov, Pavel Filonov and Kazimir Malevich, Vladimir Tatlin and Mikhail Matiushin. The consequences of this approach have been visible for a long time in Russian art, particularly in the 1920s, although non-figurative painting only interested artists for a short period of time. Malevich presented, for the first time, forty-nine Suprematist paintings at the exhibition that opened 15 December 1915 at the gallery of Nadeshda Dobytshina on the Field of Mars (Petrograd). ‘The keys to Suprematism’, he wrote, ‘lead me to a discovery that I am not yet aware of. My new painting does not belong exclusively to the earth. Earth is abandoned like a house eaten from within by woodworm. And there is actually in man, in his conscience, an aspiration for space, a desire to detach himself from Earth.’ [8]

The Spiritual Universe

For most painters, despite the discoveries of Galileo, Copernicus and Giordano Bruno, the Universe remained geocentric (from an emotional and practical point of view, that is to say, in their creativity). The imagination and structures in their paintings remain pledged to a terrestrial attraction. Perspective and horizon, notions of top and bottom were for them undeniably obvious. Suprematism would disrupt all of this. In some way, Malevich was looking at Earth from space or, in another way, his ‘spiritual universe’ suggested to him this cosmic vision. Numerous Russian philosophers, poets and painters at the beginning of the century returned to the Gnostic idea of primitive Christianity, which saw a typological identity between the spiritual world of man and the Universe. ‘The human skull,’ wrote Malevich, ‘offers to the movement representations of the same infinity, it equals the Universe, because all that man sees in the Universe is there.’ [9] Man had begun to feel that he was not only the son of Earth but also an integral part of the Universe. The spiritual movement of man’s inner world generates subjective forms of space and time. The contact of these forms with reality transforms this reality in the work of an artist into art, therefore a material object whose essence is, in fact, spiritual. In this way the comprehension of the spiritual world as a microscopic universe brings about a new ‘cosmic’ understanding of the world. In the 20th century this new comprehension lead to the creation of radical changes in art. In the non-objective paintings of Malevich, whose rejection of terrestrial ‘criteria of orientation,’ notions of top and bottom, right and left, no longer exist, because all orientations are independent, like the Universe. This implies such a level of ‘autonomy’ in the organisation and structure of the work that the links between the orientations, dictated by gravity, are broken. An independent world appears, an enclosed world, possessing its own ‘field’ of attraction-gravitation, a ‘small planet’ with its own place in the harmony of the universe. The non-representative canvases of Malevich did not break with the natural principle. Moreover, the painter goes on to qualify it himself as a ‘new pictorial realism.’ [10] But its ‘natural character’ expresses itself at another level, both cosmic and planetary. The great merit of non-objective art was not only to give painters a new vision of the world but also to lay bare to them the first elements of the pictorial form, while going on to enrich the language of painting. Shklovsky expressed this well in talking about Malevich and his champions: ‘The Suprematists have done in art what a chemist does in medicine. They have cleared away the active part of the media[11].’

At the beginning of 1917 Russian art offered a true range of contradictory movements and artistic trends. There were the declining Itinerants, the World of Art, which had lost its guiding role, while the Jack of Diamonds group (also known as the Knave of Diamonds), was quickly beginning to establish itself in the wake of Cezannism, Suprematism, Constructivism and Analytical Art. To characterise the post-revolutionary Avant-Garde, we will only address the essential phenomena of art and the principle events in the world of painting, focusing less on the work of painters than on the processes taking place in art at that time and on the issues raised by the great masters, who represent art’s summit at the time.

Ivan Puni, Still Life with Letters.The Spectrum of the Refugees, 1919.

Oil on canvas, 124 x 127 cm.

Private collection.

Olga Rozanova, Non-Objective Composition (Suprematism), 1916.

Oil on canvas, 102 x 94 cm.

Museum of Visual Arts, Yekaterinburg.

Soon after the October Revolution, a group of young painters gathered at the Institute of Artistic Culture (IZO), the People’s Commissariat for Enlightenment (Narkompros), directed by Anatoly Lunatcharsky. For them the Revolution signified the total and complete renewal of all life’s establishments, a liberation from all that was antiquated, outdated and unjust. Art, they thought, must play an essential role in this process of purification. ‘The thunder of the October canons helped us become innovative,’ wrote Malevich during these days. ‘We have come to clean the personality from academic accessories, to cauterise in the brain the mildew of the past and to re-establish time, space, cadence, rhythm and movement, the foundations of today.’ [12]

The young painters wanted to democratise art, make it unfold in the squares and streets, making it an efficient force in the revolutionary transformation of life. ‘Let paintings (colours) glow like sparklers in the squares and the streets, from house to house, praising, ennobling the eyes (the taste) of the passer-by.’[13] wrote Vladimir Mayakovsky, Vassily Kamensky and David Burliuk. The first attempts to ‘take art out’ into the streets were made in Moscow. On 15 March 1918, three paintings by David Burliuk were hung from the windows of a building situated at the corner of Kuznetsky Most street and the Neglinnaya alleyway. Interpreted as a new act of mischief by the Futurists, one could already see the near future in this action. In 1918, Suprematism left the artists’ studios and for the first time was brought into the streets and squares of Petrograd, translated in an original way in the decorative paintings of Ivan Puni, Xenia Bogouslavskaia, Vladimir Lebedev, Vladimir Kozlinsky, Nathan Altman and Pavel Mansurov. The panel painted by Kolinsky, destined for the Liteyny Bridge, was characterised by simple and lapidary forms, an image rich in meaning, without unintentional or secondary lines. The artist knew how to construct an image with few but pronounced mixes of colours: the deep blue of the Neva River, the dark silhouettes of war ships, the red flags of the demonstration that march along the quay. The watercolours of Kolinsky are not only decorative and joyful, but also characterised by an authentic monumentality. With a minimum use of forms and colours, the work acquires a maximum emotional charge.

The sketches of Puni, Lebedev and Bogouslavskaia reflect strong Suprematist influences. In these initial experiences, however, the painters conceived the principles of Suprematism in a somewhat ‘simplistic’ way, seeing it from a decorative and colour point of view only as a new procedure in plane organisation. They did not grasp the intimate sense of this movement and its philosophical roots.

Mikhail Matiushin,Movements in Space, 1922.

Oil on canvas, 124 x 168 cm.

The State Russian Museum, St Petersburg.

The ROSTA Windows (Russian Telegraph Agency) of Petrograd

In 1920-1921, the influence of Suprematism would go on to transform the revolutionary poster, created by Kolinsky and Lebedev. The first ROSTA Windows (Russian Telegraph Agency) appeared in Moscow at the end of 1919. Mayakovsky would also take an active role in their creation. According to the act signed by Plato Kerjentsev and Vladimir Mayakovsky, Vladimir Kolinsky was designated as the head of the Painting section of the ROSTA in Petrograd. He involved his friend Vladimir Lebedev, along with Lev Brodaty, in the creation and design of posters. The difficulties the young painters encountered consisted mainly of not taking as their model posters pre-dating the Revolution, as these were considered to be of mediocre artistic level; their resemblance to caricatures from newspapers, magazines, or vignettes did not help. The young ROSTA painters had an entirely different notion of the poster. They saw it as an art of great influence, simple and constructive from the visual point of view, and also impressive by its monumental size.

In two years work, a thousand posters were created, of which today only a few dozen remain. Two painters — Kolinsky and Lebedev — played a determining role in the creation of the ROSTA Windows, for they made the vast majority of the posters in which they succeeded in creating an original style typical of Petrograd. The ROSTA Windows were reproduced in large numbers. On certain proofs, the following notes have been conserved: ‘Print 2000 copies’ or ‘Print maximum (1500 to 2000).’ Of course, the artists were unable to colour such a number of prints themselves. They provided the models from which assistants coloured the whole print run in. The linocuts were painted with pure, bright aniline colours. The addition of colour was made freely, in an improvised manner. One single poster, therefore, had several variants. The colour was put not only within the contours of the drawing but, like in the lubok (popular naive Russian imagery), was often overlapping. This technical particularity, unavoidable in mass production, gave the posters the charm of a handmade work, although a printing press was obviously used in the process. Although the posters of the ROSTA are characterised by the unity of visual principles, they nevertheless reflect the individual artistic talents of Kolinsky and Lebedev. The two young painters were trained at the same school; they had a passion for Cubism, which can be seen in many of their posters. But Kolinsky is softer, more lyrical than his colleague who is more caustic and brutal. Kolinsky is demonstrative and open in the expression of his feelings. Lebedev is more severe, more conventional, and more constructive. But he succeeds better than Kolinsky in ‘engraving’ his forms. The influence of Suprematism is often seen in these works. The posters of Lebedev are visual formulas in their own style, from which nothing can be taken away or added.

Kazimir Malevich,The Principles of Mural Painting: Vitebsk, 1919.

Watercolour, gouache and

Indian ink on paper, 34 x 24.8 cm.

Private collection.

Ivan Puni, Litejny (drawing of the handbill Litejny), 1918.

Indian ink and watercolour on paper,

38.3 x 34.4 cm. The State Russian Museum,

St Petersburg.

The Sevodnia Artel

One must also mention the Artel of artists that existed in Petrograd in 1918 and 1919 under the name of Sevodnia (Today). In 1918, poets and painters congregated frequently at the house of Vera Ermolaeva. One could see there, for instance, Maxim Gorky and Vladimir Mayakovsky[14]