6,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Inspiring Publishers / ASPG

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

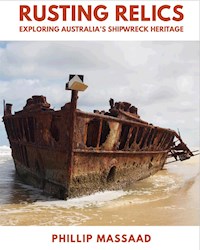

Rusting Relics is an exploration of over 80 shipwrecks and shipwreck sites along Australia's epic coastline, it covers a range of wrecks beginning with the tragedy of the Batavia in 1629 through to the dramatic grounding of he Pasha Bulker in 2007.

The lives of each ship and their passengers and crew are brought vividly to life, many met a dramatic end while others quietly slipped away into the pages of history. Each wreck is illustrated with contemporary photos and illustrations, many published for the first time and complemented by the author's own photographs showing the current condition of each wreck and site. In addition to a detailed bibliography for further reading, the location of each wreck described in this book are marked on a series of specially commissioned maps to inspire the reader to go and explore Australia's shipwreck heritage.

About Author: A student of history, Phillip has always been interested in the past and especially shipwrecks. Over the last decade and armed with several cameras, he has striven to photograph the disappearing maritime heritage of shipwrecks on Australian shores, these photographs have formed the genesis for this book.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

Copyright © 2019 (Phillip Massaad)

All rights reserved worldwide.

No part of this book can be stored, changed, sold, copied or transmitted in any form or by whatever means other than what is outlined in this book without the prior permission in writing of the person holding the copyright, except for the use of brief quotations and certain other non-commercial uses permitted by copyright law.

Publisher: Inspiring Publishers,P.O. Box 159, Calwell, ACT Australia 2905Email: [email protected]://www.inspiringpublishers.com

National Library of Australia The Prepublication Data Service

Author : Phillip Massaad

Title : Rusting Relics

Genre : Non-fiction

ISBN : 978-1-925908-77-0

Dedication

To those who survived, to those who tried and to those who never reached shore.

Acknowledgements

To my family and friends who have supported, encouraged and politely endured my eccentricities, I thank you.

A work of this scope would not have been possible without the assistance of a diverse array of individuals and institutions, in no particular order: Pieter Berkel, Simon Slee, Christian Lewis, Andii Hei, Dr Brad Duncan (Maritime Heritage NSW), Mike Scanlon (Newcastle Herald), Rona Hollingsworth (Maritime Museum of Tasmania), Gordy Ross, Freya Elmer (Auckland Museum of Transport and Technology), the staff at the Tasmanian Archives, Australian War Memorial, Sunshine Coast Regional Council, City of Newcastle Library, State Library of New South Wales, State Library of Victoria, Wollongong City Libraries and the Illawarra Historical Society, City of Sydney and Allan C. Green whose mastery of photography has left us with such a rich record of our maritime past.

A special thanks to Chuong Vu for the wonderful maps dotted throughout this book.

Introduction

Shipwrecks have always held a special allure in the imagination of people and for a young, highly impressionable child, the awe of touching the rusty bones of a wrecked ship was felt so deeply that those same emotions retain their intensity even now. This book is the result of my quest to visit shipwrecks and their sites across Australia over the past 15 years.

It is not a complete record of every shipwreck to be found on Australian shores and it is my hope to add more in future editions, particularly from the western and northern regions however with over 80 wrecks included within these pages there is a thorough cross section of ships that have met their end on the shores of Australia. The ships represent the diverse array of maritime craft that once plied the waters of the world, from speedy clippers to pioneering warships; from proud ocean liners to humble hopper barges. The stories are as diverse as the ships, from the dramatic theft of the steamer Ferret to the humble Kwinana whose lasting legacy was giving its name to a large industrial and commercial suburb. The wrecks covered in this book are detailed chronologically from the date they were wrecked and the chapters are organised clockwise by state starting with New South Wales and ending with Queensland.

It is my hope that this book will act as a lasting record of the fading legacy of these wrecks which are slowly but surely disappearing from sight through the forces of nature or in some cases, through human intervention. Wrecks do not last forever and once they are gone there will be no reminder for future generations to acknowledge the rich and often tragic maritime history that has been neglected for so long. May the following words and pictures be an epitaph which records the life, death and slow demise of the rusting relics of Australian shipwrecks.

Contents

Introduction

New South Wales

Dunbar:

Mimosa:

Austral:

Ly-ee-Moon:

Maitland:

Hereward:

Tekapo:

Itata:

Greycliffe:

Merimbula:

Malabar:

David Blake:

HMAS Parramatta:

Minmi:

Cities Service Boston:

Goolgwai:

Kate Tatham:

Newcastle Breakwater wrecks:

Cawarra:

Colonist:

Wendouree:

Regent Murray:

Lindus:

Adolphe:

Elamang:

Katoomba:

Mystery boiler:

Homebush Bay wrecks:

Unidentified Lighter:

Ayrfield:

Mortlake Bank:

Heroic:

HMAS Karangi:

Homebush Barges:

Sawmillers Reserve Barge:

Cobaki:

Trial Bay Trio:

Koondooloo:

Sydney Queen:

Lurgurena:

Sygna:

Pasha Bulker:

Smashed Dinghy:

Harbour Queen:

Adelaide:

Victoria

Loch Ard:

Speke:

Ozone:

HMVS Cerberus:

HMAS J7:

Stony Creek wreck:

Tasmania

Platypus dredger:

Lake St Clair barge:

Otago:

Westralian:

Togo:

Lake Illawarra:

South Australia

Ethel:

Willyama:

Ferret:

Hougomont:

Old Jeny:

Excelsior:

Garden Island Shipwreck Graveyard:

Seminole:

Sunbeam:

Flinders:

Killarney:

Lady Daly:

Moe:

Sarnia:

Juno:

Grace Darling:

Garthneill:

Glaucus:

Mangana:

Trafalgar:

Alert:

Western Australia

Batavia:

Omeo:

Kwinana:

Queensland

Dicky:

Maheno:

Cherry Venture:

Gayundah:

Bibliography

New South Wales

Dunbar: Death at Sydney’s doorstep

On the night of 20th August 1857 the young colony of Sydney experienced a shipwreck that traumatised the fledgling city. The loss of 120 lives was keenly felt and their deaths were all the more ironic in that it occurred barely metres away from the safety of Sydney harbour. While the wreck has been described as “Australia’s Titanic”, a more accurate comparison can be found in the drama that played out after the Thredbo landslide of 1997 where the nation was held in suspense as a solitary survivor, Stuart Diver, was rescued from the rubble. On that grim night in 1857, amidst the cold fury of a gale and a sea of death Sydneysiders were transfixed as a sole survivor was miraculously rescued.

The Dunbar was a sailing ship built in 1852 for the shipowner Duncan Dunbar and was described upon completion by the Illustrated London News as a ship ‘built for strength, stowage and durability, yet withal is a graceful model. She is extra coppered – throughout, and her iron knees and other fastenings are of enormous strength.’1 After a three year charter by the Royal Navy to take troops for the Crimean War, the Dunbar settled into an uneventful career sailing to Australia and back to England.

After a voyage of eight months, the Dunbar was at the doorstep of Sydney harbour but the stormy conditions made it difficult to locate the Macquarie Lighthouse and Dawes Light, the two harbour. In these dimly lit conditions, the Dunbar turned too early and smashed into the sheer cliffs of South Head. The oak and iron hull of the Dunbar was no match for the sandstone cliffs and relentless waves, within minutes the ship had disintegrated and the surviving passengers and crew thrown into the water. A twenty three year old Irish able seaman, James Johnson, was able to climb up onto a small ledge and hang on until daylight. In his own words he described the unfolding disaster:essential navigational aids to guide mariners through the Heads and into the safety of Sydney

“[The ship] was trying to stretch out to the eastward, her head lying along the land to the north. Then we struck and the screaming began, the passengers running about the deck screaming for mercy. The captain was on the poop deck. He was cool and collected. There was great confusion and uproar on the deck with the shrieks of the passengers. With the first bump the three topmasts fell and the first sea that came over us stove in the quarter boats, none of which were lowered. The mizzen mast went first, then the mainmast. The foremast stood a long time. It was not more than five minutes after she struck that she began to break up and then went with a great crash.”2

On the following morning as wreckage washed into the harbour, Sydneysiders began a search for survivors while the battered bones of the ship became a grim attraction with 10,000 people, close to 20% of Sydney’s population, flocking to the cliffs.3 One curious onlooker, whose identity has only been recorded as ‘Palmer’ looked over the ledge and noticed just out of reach of the waves, was a man, alive and signalling feebly for help. A derrick was set up and a young man from Iceland, Antonie Wollier, offered to go down the cliff and rescue him. The news of a survivor spread like wildfire and police had to constantly push back the crowds from the cliff edge. Antonie was able, on his second try, to reach James and haul him to safety. James had been stuck for thirty six hours and was the only survivor of the wreck of the Dunbar.

The population of Sydney turned its attention to mourning the dead which included Mrs Egan who together with her son and daughter were coming back to join their husband and father Mr Daniel Egan, a member of the New South Wales Parliament. Also lost was Adrian de Young James, the only son of H.Kerrison James, who was the secretary to the Anglican Bishop of Sydney. Adrian had been returning to Sydney with plans to join the church. At least two whole families were wiped out, Mr & Mrs Killner Waller and Mr & Mrs Myers were lost, along with each of their six children and servants.4 The wreck caused an outpouring of grief and branded itself on the consciousness of Sydneysiders that was unique in the history of Sydney. In the decades after the sinking, the story of the shipwreck was recounted in a play that in turn became one of Australia’s earliest movies, released in 1912 under the titles of “Wreck of the Dunbar” and “The Yeoman’s Wedding”, a contemporary advertisement described the film as ‘the whole of these events visualised in a manner that has never been attempted or achieved in the annals of Australian Motion Photography’; sadly no surviving prints of this movie have been found.5

In the 150 years since that tragic event, the wreck of the Dunbar has not been completely forgotten, the point of impact is known as Dunbar Head and the wreck itself was identified and protected under the Historic Shipwrecks Act of 1976. The most prominent memorial to the wreck is a large anchor displayed at The Gap, a small bay north of where the wreck actually happened. The anchor has not been positively identified as being from the Dunbar, it has been referred to as such since it was raised and put on public display. A memorial and the ships bell can be found at St John’s church in Darlinghurst. In addition, the Benedictine Monastery at Arcadia has two stained glass windows that were originally installed at St Mary’s Cathedral to commemorate Mrs Egan and her two children, these windows survived the blaze that destroyed the cathedral and were ultimately salvaged and re-used at the monastery.

Mimosa: Proximity alert

The Mimosa Rocks National Park owes its name to a ship which sank close to the distinctive pyramid shaped rock in 1863. The Mimosa was a paddle steamer that had been built in 1854 originally to operate along the Tasmanian east coast and becoming the first regular steam ship to run on this service.6 In 1860, it was sold to the Illawarra Steam Navigation which spent £11,000 on modifications and two years later, lengthened the ship by seven metres. On 18th September 1863, after departing Twofold Bay and 17 km north of Tathra; the ship ran into uncharted rocks. The captain tried to get the ship to shallow water but it sank so rapidly that two passengers, a Mr & Mrs Ivell, were trapped below deck and lost.

A survey of the surrounding area did not find any uncharted rocks and it is now suspected that the Captain did not want to admit he was off course or travelling too close to shore at the time. The masts could be seen above water and the wreck was the site of early salvage attempts before currents broke it apart and visible reminders of the wreck were lost forever. Divers who visit the wreck are treated to the sight of two boilers and the unique remains of a diagonal trunk engine while on shore a walk to the titular rock will reveal a vista of an empty ocean that was once dominated by coastal ships.

Austral: A tragic accident and an epic salvage

The new Orient liner Austral arrived in Sydney on 9th November 1882 at the completion of its third voyage; there was a sense of relief among the crew because the previous voyage had been marred by engine problems and an outbreak of smallpox. After unloading passengers and cargo the ship was moved to Neutral Bay to replenish its coal bunkers. It was common practise to load one side at a time and no one was concerned when the ship developed a list to starboard as the bunkers on that side were filled first. As coaling continued through the night of 10th November and into the early hours of the next morning, the list reached the level of the lowest portholes which had been left open and water surged in. In a matter of minutes the liner was sitting on the bottom of the harbour with its masts and funnels protruding above the surface.

James Vince, a fireman aboard the Austral described the hectic scene:

“About 4 o’clock this morning, I, along with all the other men below, was awakened by a great noise on deck. In a very short time afterwards nearly all hands appeared on deck to ascertain the cause of the disturbance. It was thought by many that an accident had occurred, and when we reached the deck the vessel began to sink, finally settling down on her starboard side.”7

The proximity of coaling barges, colliers and local vessels played a key part in rescuing almost all the crew however five were drowned in the sudden sinking.

Refloating the largest ocean liner serving the England-Australia route was a massive operation, it was the colonial equivalent of raising the Costa Concordia8 and the nearby shipyard at Cockatoo Island was tasked with the salvage. All openings underwater were closed and a wooden cofferdam built around the wreck, assembled in sections of 16 feet (4.87 metres) long and made watertight with 26,000 feet (7,924.8 metres) of canvas. Pumping began on 27th Feb 1883 and the ship was refloated on 12th March, between 300-400 men were needed to thoroughly clean the ship and remove 1,500 tons of coal still in the bunkers.9 After two weeks of work the Austral left Sydney under its own power for England. Unlike the other ships in this book, the Austral continued operating for another twenty years before being scrapped in Genoa in 1903. Today nothing remains of that dramatic night however a walk to the Lady Gowrie Lookout, one can still see the panorama of where it sank and with some imagination, recreate the sights and sounds of an army of men working to salvage the ship.

Ly-ee-Moon: Death under a lighthouse

The Ly-ee-Moon was a storied ship having originally been built in 1859 for the Opium trade between England and Hong Kong as a three masted paddle steamer. The name is an Anglicisation on Lei Yue Mun; a short channel between Junk Bay and Victoria Harbour, Hong Kong.10 Coal consumption was 75 tons a day with a top speed of 16 knots however during its days operating in Australia, the ship regularly ran between 12-14 knots.11 Its reputation as a speedy vessel led to its use as a blockade runner for the Confederacy in the American Civil War and at the cessation of that conflict, returned to service in Hong Kong waters.

It was long believed and recorded as such that the ship was used as a Japanese Imperial yacht however no record of this has been found to verify the claim, from the fragmentary evidence available the only conclusion that can be drawn is that after the end of the American Civil War the ship returned to service in the Far East.

In 1872 the ship was rammed and sunk while in Hong Kong harbour but was refloated and returned to service. Two years later the ship was rebuilt and the paddle wheels were replaced by a propeller, at about this time the ship was bought by the Australasian United Steam Navigation Company (ASNC) and used on their express run between Sydney and Melbourne.

In 1877 while undergoing maintenance at the company’s yard in Pyrmont a fire started on the main deck and the ship was completely burnt out so the opportunity was taken to rebuild the accommodation in the very latest fashion and the Ly-ee-Moon emerged in 1878 as a practically new ship, with a redesigned upper deck and only two masts. The combination of speed and luxurious fittings meant the Ly-ee-Moon was popular with travellers and for the remaining eight years of its life operated without incident.

At 12:30pm on 29th May 1886, the Ly-ee-Moon departed Melbourne bound for Sydney, onboard were forty one crew and fifty five passengers; among them was Mrs Flora MacKillop who was journeying north to visit her daughters, one of whom, Mary; would eventually become Australia’s first saint. By the evening of the next day, the Ly-ee-Moon was making good progress along the southern New South Wales coast despite worsening weather when at 9:30pm - for reasons that have never been fully determined - it steamed straight into rocks below Green Cape and its lighthouse; within two minutes the iron ship had broken in two.

The severed back half of the Ly-ee-Moon slid off the rocks and sank in deep water, taking with it everyone trapped in that part of the ship. The forward section was pushed closer to the cliff face and rolled onto its starboard side where some quick thinking crew members were able to use the mast as a temporary bridge to reach the relative safety of the rocks. In the ensuing six hours a rope was fastened to the ship and the remaining survivors crawled their way onto land. The youngest survivor, twelve year old Harry Adams, recounted his harrowing ordeal:

“I was on board the Ly-ee-Moon with my mother and little baby sister. I was in a different cabin to mother. When the vessel struck I got out of bed and saw a lot of gentlemen dressing. I asked somebody where my mother was. They said she was in the ladies’ cabin. I went there and, with my mother and sister, tried to get up on deck. The lower deck was bursting up then... There was such a lot of noise and steam blowing off and cracking. We went further forward and hung on to the pole in the saloon. The people were crying out ‘Oh God save us’ and they were praying. Thank God I did get saved. Mother kissed me and said ‘poor boy, oh Harry we are going.’ It was dark and I did not see mother after that. I clambered up to the porthole and opened it and tried to get out. I was helped by two gentlemen… We could hear the people on the after part of the ship calling out. It was a long time…I remember saying ‘Can I go ashore, captain?”12

Harry was eventually brought ashore holding onto a crewman as they dragged themselves across the rope. Daylight revealed the scale of the disaster with only fifteen survivors and scattered wreckage across the bay. As though to remind everyone of the tragedy, the ship’s bell continued to toll as the wreck was swayed back and forth by the waves before finally sinking on the following day.13

1886 was a black year for shipwrecks in New South Wales with the Ly-ee-Moon initiating a trio of wrecks. On 6th December 1886 another steamer, the near-new Corangamite, ran aground near St George Head, Jervis Bay on a voyage from Melbourne to Sydney and barely two days later, 8th December, while off the Solitary Islands near Coffs Harbour, the passenger steamer Keilawarra was sunk in a collision with the Helen Nicholl. The loss of forty people in that disaster resulted in new safety regulations that ensured coastal ships sailed with enough life preservers for all onboard. It would take the sinking of the Titanic for that logic to be applied on an international scale.

The wreck of the Ly-ee-Moon created a sensation in the newspapers of the day as it was the worst disaster in the colony since the loss of the Dunbar and utter shock at how a ship could crash headlong into a cliff beneath a fully illuminated lighthouse. No definitive reason was ever found and justice was never served. What is known is at 8:45pm the Ly-ee-Moon turned to port, towards land, to avoid an oncoming ship however this was contrary to the rules of the road and the Ly-ee-Moon should have turned to starboard, putting the oncoming ship between it and land before resuming its course. For the next forty five minutes the Ly-ee-Moon steamed straight towards the cliffs of Green Cape and its lighthouse. How this was not identified by the helmsman who made the initial turn to port, the officer of the watch Third Officer Fotheringhame or Captain Webber is tragically lost to history. The debate and controversy are dealt in more detail in two excellent books, ‘Who Lied? The Ly-ee-Moon Disaster and a Question of Truth’ by George Barrow and ‘Fatal Lights’ by Tom Mead.

The exposed location of the wreck means there is almost nothing left to see except an occasional rusted hull plate. The nearby cemetery, shabby with the passing of time and ravaged by bushfires is a sad monument to the loss of so many lives and a ship that led a dramatic and ultimately tragic life.