20,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Fachliteratur

- Sprache: Englisch

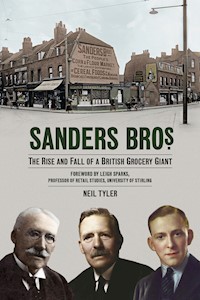

Established in 1887, Sanders Bros. was the UK's largest chain of corn, flour, seed and general produce merchants in the 1920s, trading from 154 branches in 1925 in London and the surrounding area and with a stock market value higher than Marks & Spencer. With more retail stores than Sainsbury or Tesco, Sanders Bros. was also a significant manufacturer and distributor of biscuits and grocery and a major importer of spices and rice. Taken over by a colourful group of investors, it was quickly broken up and its records destroyed in the 1950s. The story of this major business is reconstructed using published and personal sources, including family memories, photos and advertisements. This is the unique and previously untold story of a national food retail chain in the pre-supermarket era, and the lessons taught by its rise and fall.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

This book is dedicated to the memory of my mother, Sally Jean Tyler.

CONTENTS

Title

Dedication

Foreword by Professor Leigh Sparks

Acknowledgements

Introduction

1 Bethnal Green Beginnings: 1887–1899

2 Sanders’ Heyday: 1900–1925

3 Managing to Thrive: 1925

4 Boom Times and Biscuits: 1926–1929

5 Gilbertson & Page Ltd

6 Expanding and Contracting: 1930s

7 Wartime Woes: 1939–1945

8 Austerity Bites: 1946–1949

9 The Battle for Control: 1950

10 Shutting up Shop: 1951–1957

11 Looking Back on Sanders Bros

Afterword

Sources

Select Bibliography

Appendix One: Company Directors

Appendix Two: Sanders Bros Store Locations

About the Author

Plates

Copyright

FOREWORD

FOOD retailing is a fascinating subject, made all the more personal by our everyday connection with it through local shops, markets, supermarkets, and even the Internet. Food retailing and food use provide endless social insights into consumers and communities.

But in our modern world we sometimes forget that the retailing and the food we consume is ever-changing. And we forget the social and economic realities of times past, and of businesses past.

Sanders Bros casts an intriguing light on this changing world. The story that Neil Tyler has painstakingly reconstructed of this forgotten retailer is both a personal and a commercial one, shining a light into unremembered yet important spaces.

Sanders Bros was a large and successful retailer, born in the late nineteenth century but still in the inter-war period a significant presence, especially in London and South-East England. Both a producer and a retailer, Sanders’ is a story of changing times and changing lives, not least in its wartime decline and post-war dissolution.

The story is both family and business history, as well as a caution about changing behaviours, places, businesses, opportunities and values. Using novel approaches and newly available sources, this is a tour de force on the changing fortunes not only of one large retailer, but also of many people, places and products.

Leigh Sparks

Professor of Retail Studies, University of Stirling

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

THIS history owes a very great deal to many people but particularly to the enthusiasm and invaluable input of Professor Leigh Sparks of the University of Stirling, during and since his supervision of my MBA dissertation in 2009.

Many people have also contributed significantly to the piecing together and retelling of the Sanders Bros’ story, especially Gillian Caren, Gaye Thornton-Kemsley, Alison Tuke and Fiona Caren (descendants of one of the founders of Sanders Bros, Joseph Sanders) for information they provided on the Sanders family, the business and a significant number of photographs. Thanks also to Gerald Chaston and family, regarding the Chaston family and Chaston’s Flour Mill in Great Shelford, Cambridgeshire; Jenny Dixon, Ian Smith and other descendants of Ernest Fairbrother and, in particular, Andy Dixon and Susan Walker, for their creative input; Ken Amphlett, for his extensive help and memories of No. 74 High Street Barnet, the Sanders Bros store of which his father, Douglas, was manager from around 1939–51; Hazel Kerr Abel, for her great contribution to the detailed story of her grandfather, Charles Orrow; Suzy Travers and her father-in-law, Bob, for information relating to Arthur and James Travers; Mary Robinson, for information in relation to J. Gunn & Co. and her ancestors, Henry and Herbert Thomas Squire; Margaret Dexter (née Bolt), for her memories of the Sanders Bros store at Headington, Oxfordshire; Jean Mendham, for help with the story of her Mendham ancestors; Richard Ware and the other directors of Gilbertson & Page Ltd. I am grateful for the knowledge of Bridget Williams and Professor Andrew Godley, for their insight on food retailing in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries and particular insight into Sainsbury’s; attendees of the Conference on Historical Analysis and Research in Marketing (‘CHARM’) in May 2009 and 2013; Nicola Randall and colleagues of the Sainsbury’s archives at the Museum at Docklands; the staff of the Guildhall Library in London, for the invaluable support over the course of several years; Deloitte LLP for their support, in particular Richard Lloyd-Owen and Richard Hyman; the record offices and local studies libraries in Essex, Kent, Surrey, Sussex, Cambridgeshire, Berkshire, Hertfordshire, Hampshire, Bristol, Swindon, Westminster, Tower Hamlets and Newham, the London Metropolitan Archive, the British Newspaper Archive, historicaldirectories.org, the University of Leicester and the National Archives at Kew; also Matilda Richards, Juanita Hall and The History Press, for all of their help and support.

Although I have many to thank for their enormous contribution, all errors and omissions are entirely mine.

I also owe a significant debt of thanks to a great teacher and friend – my mother, Sally Jean Tyler. She was the first person to tell me about Sanders Bros and its managing director, her grandfather, and Gilbertson & Page Ltd and its managing director, her father. She sparked my interest in the subject and I hope that it does some justice to how she would have told the story.

INTRODUCTION

PIECING TOGETHER SANDERS BROS

At one level, there is nothing remarkable about this story; sadly, many British retailers have been lost – either failed or broken up. However, few market-leading retail chains with extensive store networks are lost entirely to history, and their lessons with them. Such, however, is the case of Sanders Bros.

When I started researching this large food group five years ago, I realised that the business I was looking to understand had no surviving archive, and had been entirely forgotten by the business and academic worlds alike; yet it was one of the largest food retailers and manufacturers of its day. Badged as ‘The People’s Corn and Flour Markets’, Sanders Bros had 263 food stores in 1937 (more branches even than Sainsbury’s and many more than the much younger grocery business, Tesco), employed over 2,000 people and later, in 1950, had the rare distinction of resisting a takeover attempt by tycoon financier Sir Charles Clore.

In 1887, two brothers from Bethnal Green, London, started a corn merchants business, working from No. 254 Globe Road, Mile End. Thomas and Joseph Sanders, aged 25 and 15 respectively at the time, had started to build up a business that would later be incorporated as Sanders Bros (Stores) Ltd and, in 1925, floated on the London Stock Exchange, at a value some 30 per cent in excess of Marks & Spencer Ltd, on its listing one year later.

For over half a century, the business was a significant part of the face of London high streets, and developed a major network of branch stores in the Home Counties and beyond. As with so many companies, but particularly Sanders Bros given its lack of customer registrations, the geographical spread of its stores and the nationalisation of its flour mills, the Second World War had a large, detrimental impact.

By the early 1950s, the business had all but failed. Sanders Bros was subject to two takeover attempts, the second of which resulted in the break-up of the company’s assets, and the demise of the country’s once-largest retailer and distributor of cereal products.

The Sanders Bros story recounts the development of a ‘multiple’ corn merchant (what we would now call a ‘chain’ of specialist grocery stores) from the end of the nineteenth century to the early 1950s, exactly the point in time when the supermarket concept was being introduced to Britain by innovators, copying models that had existed in the United States for quite some time.

At the outset of my investigative journey in 2008, I was determined to discover more about the business of which my great-grandfather had been chairman and managing director for over twenty years of his life; but I had one important disadvantage – no business archive had survived. In spite of this, I started the task of identifying as many pieces of information about the business, no matter how small, from as many sources as I could find.

Over time, details emerged through some traditional sources, and I was helped in this by two factors: that Sanders Bros had been a retailer with multiple shop, warehouse, factory and mill locations, and that from 1925, its shares were quoted on the London Stock Exchange. The group’s listing meant that although its reports, accounts and shareholder letters were not available in their own archive, many of them had been sent to the Stock Exchange for filing, including the chairman’s annual commentaries on the progress of the business. Similarly, the fact that there were multiple store locations across England meant that I could identify, using a combination of trade directories, electoral registers and the census returns for 1891, 1901 and 1911, the people who worked in the business and their stories. I was also able to make contact with the descendants of the founding Sanders family, who shared some very important memories, stories and photos. In this way, the available information started to take on a new dimension; not only did I have the facts and figures recorded in the accounts and the ‘gloss’ presented by the directors, but also a view of how the business worked, what they sold, the wider approach that it took, and even the identities of individual store managers. In short, I had a richer understanding of how Sanders Bros ‘ticked’.

Given the reach of the store network across Southern England by the 1930s, a large number of archives still hold individual pieces of information – an architect’s drawing here, a building application there – and in a surprisingly large number of cases, a photo of a store; even a catalogue of the biscuits that Sanders Bros manufactured and sold in large quantities.

The online British Newspaper Archive in particular has provided many articles and advertisements from local press, which shed light on the business’ everyday activities. Sources like these, detailing court cases, employee muggings, road crashes and complaints, have to be treated with caution in order not to take away an overly negative picture of the business – every business has its setbacks, and it is largely the less positive events in a company’s life that are reported by the press.

This research has been helped enormously by the recent strong growth in primary sources available on the Internet and online indexes of reference material held in British archives, which have allowed documents to be identified and links to be forged that otherwise would not have been feasible. The timing of my research coincided with some remarkable leaps in what is now achievable in that area. Even eBay provided some surprising help with additional nuggets of information – including three series of trade cards issued by Sanders Bros in the 1920s, and even one of the store’s paper bags!

With all these disparate pieces of an incomplete jigsaw puzzle, I attempted to fit them together as best I could. As with any jigsaw, some pieces locked together crisply, and others remained to one side, or did not even seem to be part of the picture at all. Every time I found a new piece of information, it added to – and often changed – the overall picture, either subtly or significantly. I knew from the beginning that not all the pieces could be found – some were lost forever, and the final piece would never be slotted neatly into place to reveal a complete picture. I have been amazed at what has been achievable with time, effort, patience and by considering numerous sources. However, the Sanders Bros picture will always remain incomplete; where possible, I have considered analogies of what we know about other contemporary food retailers – names that will be easily recognised, like Sainsbury’s and Tesco, and others less so, such as David Greig and Gunn & Co. I have also attempted to avoid unnecessary leaps of faith and to remain objective, given my family link to the business, but, in the end, the reader will have to decide whether I have done that well.

This book takes a chronological approach to recounting the story of Sanders Bros – from the early days in Bethnal Green, London, to its huge expansion in the 1920s, through the tough trading conditions of the Depression and 1930s and the devastating effects on the business of the Second World War and its aftermath of austerity. Going into the 1950s, the story of the takeover of Sanders Bros is uncovered, as well as the reasons for its weakness and what ultimately happened to the business, its assets and employees.

With radical changes seen during the seventy years of its existence, including economic, technological and some fundamental changes in the structure of grocery retailing, can we learn as much from the story of Sanders Bros as from the history and progress of today’s UK supermarket giants? Our view of British food-retail development in the decades immediately before the advent of the supermarket era tends to focus on those businesses that have flourished and survived to the present day. My hope is that the Sanders Bros story affords a very different perspective.

1

BETHNAL GREEN BEGINNINGS 1887–1899

IN the 1880s, Green Street, Bethnal Green, was a busy East End market place that teemed with a large variety of traders, such as cheesemongers, tripe sellers, corn dealers, oilmen, hatters, hosiers and bootsellers. A number of manufacturers had also set up, producing an eclectic mix of products ranging from caps to clocks, saws, cabinets and ginger beer. The Sanders family lived at No. 129 Green Street at an establishment called ‘Old Friends’ – one of over ten beer retailers on the street.

By the time of the census in April 1881, John Sanders, a former builder, was working at Old Friends as a beer retailer and was assisted at the bar by his 19-year-old son Thomas. Thomas’ younger brother Joseph (9) is known to have studied at the nearby Globe Road School and his other siblings, William (12), Hannah (8), Charlotte (5) and Alfred (4) also attended school at the time. Older twin brothers George and John (21), a bricklayer and a painter respectively, had followed in their father’s footsteps by entering the building and decorating trade. John’s wife Hannah cared for their 2-year-old daughter Clara. The eleven members of the Sanders family all lived in rooms above the bar. (Although now a hotel and standing at No. 129 Roman Road, following the renaming of Green Street, Old Friends retains its name over 130 years after it housed the Sanders family.)

It was Thomas and Joseph, with the help of a number of their family members, who started up the Sanders Bros business six years later, in 1887. This would grow to be one of the UK’s largest food retailers and wholesalers of the time, with approximately 300 branch stores across London and the South of England.

FOUNDATION

In 1887, Thomas Sanders took the step of buying a corn dealer’s business in Globe Road, Bethnal Green. The business of a ‘corn dealer’ or ‘corn merchant’ had become a flourishing trade in London in the late nineteenth century. The use of horses in London was significant at the time, working by the docks, and in public and private transportation until electric trams were introduced. As well as selling corn and flour products of all varieties, rice, pulses and dried fruit, corn merchants traded the feed for this large horse population including hay, forage, and seed for birds and poultry, such as chickens and pigeons, which were kept in significant numbers in London districts. Similarly, rabbits and dogs were kept domestically, and Sanders Bros, in keeping with the trade of many corn merchants, supplied feed for those animals as well. In her book The Romance of Bethnal Green, Cathy Ross describes:

Men, women and children lived with animals and birds, which they enthusiastically bought, sold, bred, compared, kept, raced, betted on and ate. By the 1920s Bethnal Green was the rabbit-breeding and song-bird-dealing capital of London.

Similarly, Limehouse resident Ben Thomas recalls in Ben’s Limehouse:

Back yards mostly had a fowl house and six or seven fowls, some more if the yard or back garden was big, most small yards only had rabbits.

Then some back yards had an aviary, where the men, or their sons went in for pigeon racing, what fine prizes a lot of them won, cups and certificates. A lot of money, time and skill was spent making aviaries, fowl and pigeon sheds. Some breeds of fowl that were kept were, Leghorns, Wyandotes, Orpingtons, Rhode Island Reds, not forgetting Bantams. Pigeons were of the racing type and the aviaries held a mixture of linnets, canaries, chaffinches etc.

The business that Thomas Sanders had decided to take over had previously been run by a William Nash, trading under his own name at No. 254 Globe Road, Bethnal Green, immediately prior to Thomas Sanders setting up business there. Before turning his hand to the world of a corn chandler, William Nash, who had been born in Lambeth in 1827, had worked as a ‘corn meter’ (an official who measured weights of corn at markets). In the early 1860s, William Nash had worked as a deputy corn meter, like his younger brother Robert, living in Lambeth prior to his marriage in 1868. William Nash’s father, Jacob, like Thomas Sanders’ father John, had worked as a licensed victualler in later life. By 1879, Nash had amassed sufficient capital to run the small store at No. 254 Globe Road.

The details of the administration of his personal estate show that William had died at the place of his work, 254 Globe Road, Bethnal Green, on 23 March 1886, aged 59. The then 25-year-old Thomas Sanders appears to have purchased the business from Nash’s widow, Sarah Gale Nash, who had been left £167 (about £15,000 in today’s terms) by her husband.

Commercial confidence and an entrepreneurial spirit seem to have led Thomas Sanders to take on the concern and develop the business from its Globe Road premises – he had learnt the ways of retail through his time in his father’s beer retail business. Probably of significance to the step Thomas took was that his mother’s family, the Stichburys of Bethnal Green, appear to have run a number of grocery, greengrocery and tea stores in the neighbourhood. Thomas’ grandfather, Daniel Stichbury, for example, is shown in the 1871 census as having a greengrocery business at nearby No. 141 Globe Road, and his uncle, Henry King, operated two greengrocery stores on Green Street (now Roman Road), Bethnal Green, employing Thomas’ older brother John Daniel in the 1880s.

Location of the first store, at No. 254 Globe Road, Bethnal Green (marked by the triangle), taken on by Thomas Sanders in 1887. The circle on Green Street (now Roman Road) marks the location of Old Friends, the beer retailer at No. 129 Green Street, where Thomas assisted his father in 1881.

Although Joseph and Charlotte Sanders seem to have joined their older brother Thomas in the early growth of the Sanders Bros business, other siblings were yet to do so. Their brother William Sanders, for example, who would later become a partner in the business, appears to have set up as a builder, and in the 1891 census is recorded as such, age 22, and is marked as an employer.

John Sanders had run Old Friends from around 1879–85. By 1886, one George Sainsbury (no relation to John James Sainsbury, the founder of J. Sainsbury provision merchants) had taken over the business; probably due to John’s ill-health as he retired that year and was to die in late 1889. The timing of his father’s retirement seems to have coincided with Thomas taking on the Globe Road corn merchant’s business; as Thomas was not a beneficiary but a witness to his father’s will, this indicates that he may well have received some capital when his father withdrew from Old Friends.

EARLY DEVELOPMENTS

In the early years, the business traded under the name of ‘Thomas Sanders, Corn Merchants’ at Nos 254 and 256 Globe Road, Bethnal Green. Electoral registers for Bethnal Green North East from 1890–92 show Thomas Sanders as having a right to vote because of his ‘house & shop’ and that he was living at the time at No. 254.

In the national census of 1891, Thomas, Joseph and their sister Charlotte, then 29, 19 and 15 years old respectively, are recorded living at No. 254 Globe Road. In the first few years, it seems clear that teenage Joseph was not yet considered a partner in the venture, as Thomas is shown as being a ‘corn dealer’ and is marked as an employer, whereas both Joseph and sister Charlotte are described as a ‘corn dealer’s assistant’ and ‘employed’.

The use and residents of the premises at Globe Road seem to have varied quite a bit: No. 256, for example, was taken on by Thomas in 1889, but in the census two years later, the building was occupied by two families – those of George Goff, a tea cooper and John Whaymand, a bricklayer.

The year of 1891 saw the opening of Thomas’ second branch store, at No. 87 James Street, Bethnal Green, not far from the first store on Globe Road. The sign over the shop proudly bore Thomas’ name, the founder of an expanding business.

The years 1892 and 1893 could be presumed to be ones of stress for Thomas. His business was expanding and trade increasing, but a significant problem of bad debts was taking a grip. Late in 1893, things came to a dramatic head as Thomas became severely cash constrained and was not able to meet the debts to his own suppliers: a receiving order was issued for his bankruptcy in September, and the first meeting of his creditors took place on 4 October.

Entry for Thomas Sanders in the Corn Merchants section of the 1891 London Trade Directory (excluding London suburbs). (Courtesy of www.historicaldirectories.org and the University of Leicester)

Just five years after he took over the corn merchants, Thomas was to be declared bankrupt and his application for discharge was suspended for three years, meaning that he would only be discharged on 19 June 1897. The London Gazette records the terrible state of Thomas’ business and the grounds given in the order for refusing to grant him an absolute order of discharge:

Bankrupt’s assets are not of a value equal to 10s. in the pound on the amount of his unsecured liabilities; that he had omitted to keep such books of account as are usual and proper in the business carried on by him, and as sufficiently disclose his business transactions and financial position within the three years immediately preceding his bankruptcy, had continued to trade after knowing himself to be insolvent; and had been guilty of misconduct in relation to his property and affairs, namely: in collecting and applying to his personal use about £40 book debts, after committing an act of bankruptcy and at a time when he was hopelessly insolvent and several creditors held Judgements against him.

The first and final dividend paid to Thomas’ creditors was in fact just 2s per pound (i.e. just 10 per cent), paid on 1 June 1894 at the office of the trustee, Oscar Berry & Carr, of Monument Square, in the City.

The bankruptcy would have had a profound personal impact on the Sanders family, especially Thomas, now aged 32.

It may be easy to imagine that Thomas’ bankruptcy would have led to the financial ruin of the family, but electoral registers and trade directories reveal two significant changes that were to take place to the form of the business. Firstly, from 1895, ownership of No. 254 Globe Road had passed from Thomas Sanders to William and Joseph Sanders, his brothers (now 28 and 23 years old respectively); and secondly, the London Post Office directory of 1895 refers to ‘Sanders Brothers’ rather than ‘Thomas Sanders’ at Nos 254 and 256 Globe Road, Nos 85 and 87 James Street and a new branch at No. 10 Bonner Street, Bethnal Green.

What appears to have happened is that William and Joseph Sanders, who were not in partnership with Thomas at the time of his bankruptcy in 1893, took over the running of the business that their older brother was prevented from leading. It would seem that the properties at Globe Road and James Street were not owned, and thus were not Thomas’ assets to be sold to clear his debts. Accordingly, William and Joseph were able to pick up the rental charges and continue business from these stores. Although Joseph is known to have been employed by Thomas in the early years, his financial difficulties may have been the only reason that William Sanders was to become involved in the business, and the reason why ‘Sanders Bros’ as a trading name was to arise.

Thomas’ significant bad debts appear to have arisen from the fact that in the first five years of the business there may have been more corn dealing and wholesaling, on credit, rather than there being a very high proportion of cash sales to the public through branch stores.

Entry for Sanders Bros in the Corn Merchants section of the 1899 London Trade Directory (excluding London suburbs). (Courtesy of www.historicaldirectories.org and the University of Leicester)

The years subsequent to 1894 seem to have heralded a marked change in strategic approach, which was to focus significantly on opening shops and selling goods for cash to the public through a wider network of retail stores. By the time of publication of the 1899 Kelly’s Trades’ Directory for Central London alone (excluding suburbs), the list of trading locations for Sanders Bros extended to eleven separate stores. A comparison of the 1899 list with its 1895 equivalent shows that two of the new store locations, No. 231 Mile End Road and No. 45 Ben Jonson Road, had been taken over from the ‘London Corn & Forage Co.’, which continued to trade from its main store at No. 268 Kentish Town Road.

It is understood that Sanders Bros took over the rental of the two London Corn & Forge Co. stores rather than acquiring the freehold. Taking over the location of an existing corn chandler’s store is something Sanders Bros repeated when they took over No. 71 Shepherdess Walk from George Yeomans at some point between 1895 and 1897, and again over the course of 1901/2, when they took on the trading location of No. 171 Caledonian Road. The Caledonian Road store had been acquired from Simes Ltd, a corn merchants that, by 1900, had three stores across London, and which had been established by John Evelyn Simes. In October 1901, Simes Ltd’s assets had been possessed by a receiver for its debenture holders, at which point it seems that Sanders Bros took on the lease of No. 171 Caledonian Road. The Simes Ltd manager at this branch, Thomas Henry Emblem, who had been living above the store since 1899, was to work for Sanders Bros, first as a warehouseman and later as a store manager.

By the turn of the century, the competitive environment for London corn merchants was becoming intense, and a number of key players were emerging and developing their store network significantly.

LONDON CORN MERCHANT COMPETITORS

By 1889, some 300 corn merchant businesses had grown up at various places across London, many of them with just one trading location. At this stage, the only corn merchants with three or more trading locations listed are the London Corn & Forage Co., George Hislop, Sawkins & Clegg, Thomas Swain and Alfred Charles Taylor. Each of these had three branches, but, by 1895, Sanders Bros had grown to three stores, whilst the other businesses either had not increased their branch portfolio, or had apparently gone out of business entirely.

Sanders Bros stands out as the largest corn merchants in London in 1900, with eleven trading locations in Central London alone, and a further eleven in the London suburbs, Middlesex and Essex. In the subsequent ten years, three other major corn merchant businesses were significantly developing their London store network: Hood & Moore (The New) Ltd, with eight trading locations by 1909; Benjamin Smith & Sons, with nine locations; and A.C. Taylor Ltd (formerly Alfred Charles Taylor), with eight trading locations.

By 1910, Hood & Moore Ltd, a substantial retail and wholesale corn merchants business, had folded, making losses and unable to pay the dividend on its preference shares. By 1915, both A.C. Taylor and Benjamin Smith & Sons were continuing to trade, but from depleted trading locations. Surprisingly little is known or can be identified about these three competitors, but it is clear that whether due to the relative success of branch stores opened, financing, operating model, or other factors, Sanders Bros was the runaway winner as regards growth in the corn merchants industry in London by 1915, with over forty trading locations listed. Competitors survived but did not develop their store network; both Benjamin Smith & Sons and A.C. Taylor Ltd were to continue until at least the 1920s.

AN EARLY INSIGHT INTO SANDERS BROS SUPPLY OF GOODS

By 1900, Sanders Bros had started to sell not only the goods most traditionally associated with corn merchants but it had diversified to sell goods that might be described as ‘grocery’. The British Food Journal of April of that year recorded that:

At the North London Police Court, on March 27, before Mr Fordham, Saunders Bros [sic], of Globe Road, Mile End, were summoned by the Islington Vestry for selling as pure malt vinegar an article which was not of the nature, substance, and quality demanded. Inspector Fortune stated that he purchased the sample in question at a shop in Blackstock Road, Finsbury Park. The Public Analyst certified that the ‘vinegar’ contained 5.10 per cent. of acetic acid, 0.46 per cent. of solid matters, and 94.44 per cent. of water. The ash amounted to 0.02 per cent., and contained a trace of phosphoric acid. The defence was that the assistant made a mistake by serving what was known as table vinegar for malt vinegar. Mr Fordham inflicted a fine of £3, and £2 2s. costs.

The article shows that the business was of course dependent on the store managers to provide the public with appropriate goods, but, it seems, given the size of the fine compared to others in the same journal, that Mr Fordham was not inclined to be lenient on Sanders Bros. Later cases have also been found involving their retail supply of biscuits, egg self-raising flour and golden syrup in other branch stores, which also led to them receiving quite substantial fines.

In August 1904, an interesting article was also published as far afield as Devon during the volatile period of wheat prices in the first decade of the 1900s:

The London corn merchants are not taking fright at the wheat gamble in the United States, and most of them are more optimistic as to the future supplies than the American speculators would like them to be.

‘Suppose wheat goes up to 40s, that would not make bread more than 6d a quartern, and we are paying that, or nearly as much, in some districts now.’

The speaker was a member of the firm of Sanders Bros, of Limehouse, who also pointed out that the worst estimates of a week or two back as to the yield had been considerably modified recently.

‘My opinion is,’ he continued, speaking to a representative of a London contemporary, ‘that the American operators, having at last got the public to come into the gamble, will begin to unload on them, and then down will come the prices.

‘The shortage has scarcely made itself felt seriously, if there is any considerable deficiency. India has a very large supply, including a great deal left over from last year. Some parts of Russia have also a good crop, better than was expected; and France, which was supposed to show a considerable shortage, has turned out much better than was expected, which lessens her call on the supplies from elsewhere.

‘And the home crop, although the area of wheat cultivation is rather less, shows a very fine quality. Australia has given a good crop also, and the River Plate supply, which comes in very late, is a heavy item this year. Moreover, a good deal of the scare is due to the fact that we look almost exclusively at the American market – America is getting such a very large population that eventually she will require the whole of her own crop, and will interfere less in the European market in the future than she has done in the past.

‘A recent report from Manitoba shows that the shortage at one time anticipated had not occurred, the yield being of very fair average.

‘In the London wheat market all the big houses are holding back, in the hope of a reaction. The large baking firms have bought enough flour to keep going for some considerable time, and it is only the small, hand-to-mouth bakers, who are forced to buy, that do so.’

The article is insightful in that it shows a Sanders Bros business with its finger on the pulse of the global supply situation for wheat, and implies they are buying discriminately from a number of these foreign markets, making use of the scale of the Port of London.

LARGER PREMISES

‘After the first few years, a policy of opening Branch shops was adopted, and in 1900 twenty-two branches were open. At this date, it became necessary to secure larger and more suitable headquarters and accordingly premises were purchased at Stepney.’ This statement featured in the Sanders Bros prospectus when the company’s shares were listed on the London Stock Exchange in 1925.

The growth in store numbers up to 1900 amounts to more than one per year; whilst it appears most likely that this would have been financed through cash flows of the thriving business, rather than an input of additional capital into the business, this cannot be known for certain.

At some point, no later than 1903, the Sanders brothers appear to have taken the decision to move their warehouse and head office to Nos 111–3 Narrow Street, Limehouse, taking up the premises that had previously been used by Messrs Lefroy and Craddell’s wholesale beer business. For a short period at the turn of the century, Sanders Bros had premises at No. 111 New Corn Exchange, which was cited as the main business location, and may have included warehousing, administrative offices and stands in the large New Corn Exchange building, although by 1915 it had been vacated.

Location of Sanders Bros premises on Narrow Street in Limehouse (c.1902–23). The main offices were at Nos 111–3 Narrow Street, although at various stages included No. 98 Narrow Street (Molines Wharf) and No. 115, extending from Ropemakers Fields to the north and running to the edge of the Thames at Duke Shore Steps.

The Narrow Street site (which eventually extended from Nos 109–15 Narrow Street) was by Duke Shore Wharf on the north side of the Thames, by Limehouse Basin, and was therefore advantageous to Sanders Bros for its proximity to the London Docks. That it provided significantly greater space compared to No. 254 Globe Road, to support the increasing network of stores, seems evident.

Sanders Bros’ Narrow Street premises are part of the evocative recollections of Ben Thomas in Ben’s Limehouse:

Sanders Brothers were corn chandlers and seed merchants. They had a chain of shops nearly all over London, they sold dried fruit, haricot beans, dried peas, brown sugar and oats of different kinds. Their firm stretched from Ropemaker’s Fields to the water side, where barges were loaded and unloaded with their merchandise. Besides having their own horses and carts, they also had their own steam wagons, so they employed a lot of men, besides the women to mend and make their sacks.

… Narrow Street, like its name was very narrow, and at places, only one horse and cart could get by. So at Duke Shore, where Sanders the big corn chandlers had their big warehouses, they used to load up their vans with the result that all the other traffic was held up until loaded. The river used to come more inland, where the old Borough Yard was, and opposite bales of hay were stored, so sometimes you walked under the bowsprits of the sailing barges as the hay was being unloaded.

It is likely that the hay referred to in Ben Thomas’ account was Sanders Bros stock for sale in their stores as horse feed.

SNAPSHOT AT THE TURN OF THE TWENTIETH CENTURY