Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

'A rollicking romp.' – Mail On Sunday 'Compelling, authoritative and as readable as the best airport thriller. It fizzes with crime, fame, power and illicit sex.' – Jeremy Vine 'A timely and important book. It's quite remarkable how one building has played host to such debauchery. If only the walls could talk…' – Iain Dale Designed as a city dwelling for the modern age, Dolphin Square opened in London's Pimlico in 1936. Boasting 1,250 hi-tech flats, a swimming pool, restaurant, gardens and shopping arcade, the complex quickly attracted a long list of the affluent and influential. But behind its veneer of respectability, the Square has become one of the country's most notorious addresses; a place where the private lives of those from the highest of high society and the lowest depths of the underworld have collided and played out over the best part of a century. This is the story of the Square and its people, an ever-evolving cast of larger-than- life characters who have borne witness to, and played pivotal roles in, some of the most scandalous episodes of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. From Oswald Mosley and the Carry On gang to allegations of systematic sexual abuse, it is a saga replete with mysterious deaths, exploitation, espionage, illicit love affairs and glamour, shining a light on the changing nature of British politics and society in the modern age.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 499

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

SIMON DANCZUK is the former MP for Rochdale and co-author of the bestselling Smile for the Camera: The Double Life of Cyril Smith (Biteback, 2014). He has also written extensively for the national press.

DANIEL SMITH is the author of the acclaimed The Peer and the Gangster (The History Press, 2020).

SD: For Milton and Maurice

DS: For Rosie, Charlotte and Ben

Alas! the devil’s sooner raised than laid.

So strong, so swift, the monster there’s no gagging:

Cut Scandal’s head off, still the tongue is wagging.

David Garrick’s ‘Prologue’ to Richard Brinsley Sheridan’s The School for Scandal

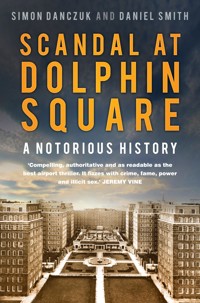

Cover photograph: Dolphin Square. (Chronicle/Alamy)

First published 2022

This paperback edition first published 2023

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Simon Danczuk and Daniel Smith, 2022, 2023

The right of Simon Danczuk and Daniel Smith to be identified as the Authors of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 75099 982 3

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CONTENTS

Introduction

1 Movers and Shakers

2 The Mirror Crack’d from Side to Side

3 The Gathering Storm

4 The Square at War

5 ‘M’ is for Mosley

6 Doves, Hawks, Heroes and a Government in Exile

7 Life Resumes

8 In the Shadows

9 Champagne and Princesses

10 ‘You have to play it cool, real cool, man’

11 Bringing Down the House: A Drama in Two Acts

12 All Change

13 Crimes and Misdemeanours

14 Carry On Up the Dolphin

15 Murder Comes to the Square

16 Political Blues

17 The End of the Party

18 David Ingle

19 Caned

20 False Accounts

21 Any Other Business

22 ‘Credible and true’

Afterword and Acknowledgements

Notes

Bibliography

Map of Dolphin Square. (FourPoint Mapping)

INTRODUCTION

Dolphin Square will, for many reasons, be London’s most distinguished address. It will carry the prestige associated with many residents notable in public life and society. Members of Parliament, people of title, Government Officials and Professional men are among those who have been attracted as Residents to Dolphin Square by reason of its unique location and exceptional appointments.

Dolphin Square promotional brochure (1935).1

When Dolphin Square officially opened in 1936, it was never intended to be just another block of flats. It was meant to offer a glimpse of the future – a city dwelling for the modern age. Twentieth-century living at its most hi-tech and aspirational. Nor was there any pretence of egalitarian classlessness. These were apartments for the affluent and the influential, the movers and shakers, the people who ran the country and made it tick. Sure, you didn’t have to be a member of the super-rich (although if you were, then ‘Welcome!’) but you needed a certain standing and a good income to secure a tenancy. (There have only ever been tenants at Dolphin Square – it has never been possible to buy a property outright.)

Located in Pimlico, on the north bank of the Thames and just up the road from Westminster, the Square soon filled with politicians, civil servants, military figures, lawyers and businessmen, the mix liberally seasoned with artists, writers, entertainers and other celebrities. There were a fair few working-class faces too, but they were there to serve – as caretakers, errand boys, cabbies, tradesmen, shopkeepers and the like, all cogs in the Dolphin Square machine that has ensured life runs smoothly for those who can afford to live there.

The complex has been likened to a citadel. Its tall blocks – forged from reinforced concrete and beautified with brick facades – are indeed imposing as they rise up from the development’s calming and beloved gardens. There is a sense of ‘the community within’ and the foreboding world beyond. Others have likened it to a village, a self-contained hamlet in the city, where the mundanity of everyday life sporadically gives way to gossip, drama and scandal. But Dolphin Square is perhaps more accurately described as a high-rise suburban oasis in the metropolis. A bolt hole for those whose social status relies upon the hurly-burly of ‘being in town’ but who, when the evening draws in, want some respite from it all. A place where they may put away the public face, hang up the suit, pour a drink and be themselves. For many residents, their apartments have been their main homes, while for others they’re but a pied-à-terre. For more than probably want to admit it, Dolphin Square has also been a place to hide away illicit lovers. But for nearly all, it has provided a sense of sanctuary.

Some residents have stayed for decades while others merely pass through. With an ever-evolving cast of thousands, much that has gone on here over the decades is unremarkable, in the way that most lives most of the time are unremarkable to the world at large. But there is always the whiff of gunpowder in the air at Dolphin Square. Sometimes it is just a faint, far-off aroma that you can hardly detect. Other times – bang! – there it goes, the combustible mix explodes, filling the nostrils with smoke and you can only wait for it to clear to see who is okay and who has been caught in the carnage.

Dolphin Square could never be described as a microcosm of the nation as a whole. It is too selective, too much of the Establishment for that. Rather, it is a stage set upon which countless dramas in the nation’s life and in the lives of some of its most prominent public figures have played out in miniature (and every now and then as exaggerated, surround-sound, 3D technicolour extravaganzas, too). It has hosted representatives of every imaginable political hue, from the far left to the far right and everything in between. There have been spies and their spymasters, revolutionaries, diplomats and democrats, even armies in exile. Famous love stories have played out, along with monstrous betrayals and sex scandals that felled governments. There have been tragedies, suicides and murder, tales of extraordinary bravery and derring-do, not to mention an enormous dollop of British eccentricity.

It is all to be found in this old place – famous and infamous at the same time – behind the front doors and along the corridors, down in its swimming pool and restaurant, through the shopping arcade and into the gardens. The walls whisper their secrets and sometimes tease with half-truths and lies. Stare into the famous ornamental pool with its elegantly sculpted dolphins, and you may just catch a reflection of our society over the best part of a century. The cultural and political landscape has shifted much over the years, but still Dolphin Square serves as a haven for that class of doers and influencers who mould our lives – a space where the private and the public collides with perhaps unique regularity and consequence. This book, then, unpicks some of the stories that have made Dolphin Square such a notable address – a modern ‘school for scandal’. Only time will reveal what other tales we are yet to discover …

1

MOVERS AND SHAKERS

What we now know as Pimlico (its name probably derived from that of the landlord of a popular hostelry over in Hoxton) was for many centuries a stretch of nondescript marshland that came to border an array of desirable neighbourhoods – Chelsea, Knightsbridge, Hyde Park and St James’s Park. The land was owned by the aristocratic Grosvenor family who, in the first half of the nineteenth century, partnered with an ambitious builder called Thomas Cubitt, a man of rare vision who would reshape several stretches of the city. It was he who first sculpted Pimlico into a residential neighbourhood catering for an overspill of the middling class gradually shifting west from the centre of London.

Cubitt located his Pimlico works on the site of what is now Dolphin Square, and it remained a hive of industry until his death in 1855. His son then reluctantly took over the family business and gradually the works were turned over to the army, who used it as a clothing depot. As the century rolled by, Cubitt’s original vision of a middle-class utopia gave way to something rather more down at heel. In 1902, Charles Booth noted in one of his famous surveys of the city that Pimlico still possessed ‘shabby gentility’ but showed signs of ‘decay’ and ‘grimy dilapidation’.1

Matters eventually came to a head in the 1930s. There were still a few pockets of middle-class domesticity but these tended to have faded, the residents of those neighbourhoods just about clinging on but generally not so well off to be able either to move to a more upmarket area or to ensure the good upkeep of their existing properties. Meanwhile, an increasing number of B&Bs and dosshouses had sprung up, while some streets were so ravaged by extreme poverty that they were little more than slums.

Yet there had been a vast upsurge in the number of people employed as civil servants in the city since the end of the nineteenth century, creating a demand for homes within easy reach of Westminster to suit the desires of this professional class. As things stood, there were simply not enough properties to meet the need. In addition, the army was preparing to relocate its clothing depot from its home in Cubitt’s old building works and were keen to stop paying the Grosvenor estate its not insignificant rent. Just as it had been a century earlier, the area was ripe for a shake-up. Cubitt’s attempt to turn Pimlico into a destination neighbourhood for London’s burgeoning middle class had only been a partial success. Now was a chance to finish the job.

The ‘new Cubitt’ for a while looked likely to be an American developer called Fred French. He purchased the freehold to the army depot site from Hugh Grosvenor, the Duke of Westminster, with an eye to creating a development modelled on successful projects he had overseen in the US. In particular, he wanted to replicate the success of his Tudor City development. Built in Manhattan in the 1920s, it was a complex that managed to meld the aspirations of the suburban middle classes to city skyscrapers. That was the dream for his Pimlico project, which was initially to be called Ormonde Court. But French soon ran up against a problem – the economic slump on both sides of the Atlantic was straining his company’s finances to near breaking point. Unable to secure the necessary finance, he began a desperate search for a building company to partner with.

Eventually, he alighted upon Costains, a family firm with a well-established reputation for speculative projects. They initially agreed to pool their talents but it was not long before French agreed to sell Costains his interest in the project. Costains then brought in architect Gordon Jeeves to revise the plans, while Oscar Faber was employed as consultant engineer. (Albert Costain, a director and brother of the company’s managing director, R.R. Costain, would serve as MP for Folkestone and Hythe between 1959 and 1983. That the company straddled the world of construction and politics no doubt helped inform the design of the Square, built in no small part with the political class firmly in mind.) Building began in September 1935 on the first of some 1,200 apartments on the 7.5-acre site. The intention was that Dolphin Square should house some 3,000 people by the time it was finished.

The first completed tranche of the development was officially opened by Lord Amulree on 25 November 1936. Amulree was a barrister and Labour politician who’d served as Secretary of State for Air in Ramsay MacDonald’s administration at the beginning of the 1930s. Also in attendance that day was Duff Cooper, the Secretary of State for War and MP for the nearby Westminster St George constituency. As a junior minister several years earlier, it had fallen to him to announce the closure of the army depot on which Dolphin Square now stood. Cooper had a love for a boozy dinner and possessed a liberal attitude to marital fidelity but, as far as we know, the opening went off without a hitch. It would not be long, though, before misbehaving politicians were starting to make their mark at the new apartments.

Although much of Dolphin Square was yet to be completed, it was already easy to see the appeal. The flats themselves benefitted from the latest soundproofing technology and came with such mod cons as fitted kitchens with fridges and self-controlled cookers, while telephones were also installed as standard. There were options to suit a variety of pockets too – you could get anything from a bedsit from £75 per year to a seven-room suite with provision for a maid from £455. But it was the abundance of extra amenities that really set the Square apart. As well as the gardens (which, rather than the buildings, were given a grade II listing in 2018), shops, restaurant and swimming pool (said to be based on the original Paris Lido), there was a library, beauty parlour, theatre booking office, laundry service, on-site childcare provision, a huge underground car park, valeting, shoe cleaning, errand boys and multiple postal collections and deliveries every day. If you so desired, it was quite possible to enjoy an elevated lifestyle without ever having to leave the Square again. It truly lived up to the aspiration expressed in a 1935 promotional booklet that residents might enjoy ‘at the same time most of the advantages of the separate house and the big communal dwelling place’.2 Reflecting the chauvinism of the day, one of the few concerns expressed in the advertising blurb was that ‘The Dolphin lady may be spoiled’. With so many of the concerns of domestic life addressed, there was a fear that ‘fortunate wives will not have enough to do. A little drudgery is good for wives, perhaps.’3

By the time Dolphin Square was completely finished in 1938, there were a total of thirteen Houses, each named after a significant figure from British naval history: Beatty, Collingwood, Drake, Duncan, Frobisher, Grenville, Hawkins, Hood, Howard, Keyes, Nelson, Raleigh and Rodney. These names tied in with the aquatic theme of the development but they also fitted into a wider narrative, one that spoke of British prestige, public service and personal glory. In short, these were the sorts of figures that the residents could look up to, and perhaps even hang a portrait of on the walls. Even if you weren’t a military sort, if you were more likely to wear a bowler hat than an admiral’s tricorn, there was the sense that within these buildings resided the sort of people who made this island nation great. As a verse published in Truth in December 1952 put it:

Since Admiral’s dare watery graves,

Where’er Britannia rules the waves,

It’s eminently fair

That theirs is the exclusive right

To have their names in letters bright

Displayed in Dolphin Square.4

So, who was there among Dolphin Square’s early intake? Which names stand out among the lords and ladies, the vice admirals, majors and colonels, the city financiers and captains of industry, the poets and playwrights, the silver screen heartthrobs and West End hoofers?

Arguably, the most significant contemporary political figure in the 1930s was Arthur Greenwood, Clement Attlee’s deputy leader of the Labour Party. Greenwood, a tall, rather awkward Yorkshireman and not renowned as a great orator, moved into Keyes House in 1939, just as he was about to enjoy his finest moment in the House of Commons. On 2 September, as Britain stood on the brink of war, Attlee was in hospital for a medical procedure so the responsibility to speak for the party fell to Greenwood. Hitler’s invasion of Poland had commenced the previous day – an event set to trigger Britain’s entry into the war to defend its ally. But to the disquiet of members on both sides of the House, there was little sign of the Conservative Government putting its military might into action. Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain gave a holding speech in which he dangled the possibility that a negotiated peace might still be achievable, even as German troops swarmed over Poland. Besides, any British action must wait until France was ready to assist. Greenwood got to his feet, encouraging shouts coming from all directions. Notably, Leo Amery, the arch Conservative anti-appeaser, urged him to ‘Speak for England, Arthur!’ A clearly nervous Greenwood began his address, and soon found his rhythm:

I am speaking under very difficult circumstances with no opportunity to think about what I should say; and I speak what is in my heart at this moment. I am gravely disturbed. An act of aggression took place 38 hours ago. The moment that act of aggression took place one of the most important treaties of modern times automatically came into operation. There may be reasons why instant action was not taken. I am not prepared to say – and I have tried to play a straight game – I am not prepared to say what I would have done had I been one of those sitting on those Benches. That delay might have been justifiable, but there are many of us on all sides of this House who view with the gravest concern the fact that hours went by and news came in of bombing operations, and news today of an intensification of it, and I wonder how long we are prepared to vacillate at a time when Britain and all that Britain stands for, and human civilisation, are in peril … if, as the right hon. Gentleman has told us, deeply though I regret it, we must wait upon our Allies, I should have preferred the Prime Minister to have been able to say to-night definitely, ‘It is either peace or war.’ Tomorrow we meet at 12. I hope the Prime Minister then – well, he must be in a position to make some further statement. And I must put this point to him. Every minute’s delay now means the loss of life, imperilling our national interests … imperilling the very foundations of our national honour, and I hope, therefore, that tomorrow morning, however hard it may be to the right hon. Gentleman – and no one would care to be in his shoes to-night – we shall know the mind of the British Government, and that there shall be no more devices for dragging out what has been dragged out too long. The moment we look like weakening, at that moment dictatorship knows we are beaten. We are not beaten. We shall not be beaten. We cannot be beaten …5

Greenwood had proved the old ‘Cometh the hour’ adage and Chamberlain was left in no doubt by his whips that the House would brook no further prevarication. Chamberlain declared war on Germany the following day. Rumour has it that Greenwood steeled his nerves with a few drinks in the Commons bar before his speech on the 2nd. One suspects he might have calmed his post-match nerves with a few more back inside Dolphin Square.

Nor would Greenwood have been short of fellow Labourites to consort with. For one, his son Tony was still living with his parents in the Square. The following year Tony married Jill Williams and subsequently they became something of a Labour power couple. She designed the iconic ‘Make do and mend’ pamphlets during the war and he would go on to hold several ministerial posts in the 1950s and ’60s, including Minister of Housing and Local Government, Minister of Overseas Development and Secretary of State for the Colonies. A left-winger, in 1961 he unsuccessfully challenged Hugh Gaitskell for the party leadership. The Greenwoods were also prominent figures in the anti-nuclear Aldermaston Marches and were founding members of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND) in 1958.

The MP Josiah Wedgwood, another party stalwart, had taken a flat in Howard House in 1937, by which time he was already into his seventh decade. A descendant of the legendary eighteenth-century potter and industrial giant who shared his name, Wedgwood had been a member of the Liberal Party when he first took a seat in Parliament in 1906 but joined the Labour ranks after the First World War, in which he had seen active service. By the time he arrived at Dolphin Square, he was firmly established among the anti-appeasers in the Commons and was a notable campaigner in the interests of those attempting to flee Hitler’s terror on the Continent. He was also a prime example of the sort of ‘old money’ who could have afforded to live in a much grander, more traditional London abode than Dolphin Square but who had instead bought into the Costains’ vision of modern living. Yet even Wedgwood could not avoid a little scandal once a resident of the Square. In January 1938, his wife Ethel was fined £1 for dangerous driving, the judge suggesting down Ethel’s ear trumpet that she ought to have a driving test. (When it came to motoring indiscretions, she was in good company. An additional wayward Dolphin Square car owner was Diana Asquith, wife of Michael Asquith and granddaughter-in-law of Herbert Asquith, Britain’s Liberal prime minister from 1908 until 1916. She was fined £2 for non-payment of road tax in 1939, an oversight she put down to a bout of illness.)

Whatever his wife’s suitability to driving, Wedgwood was able to weather that particular indiscretion and continued with his life of public service. When war arrived, he joined the Home Guard and, in 1942, Churchill elevated him to the Lords, ending his thirty-six-year Commons career. Perhaps tellingly, he died just a year later.

Dolphin Square boasted yet another Labour MP in this period, too. Arthur Henderson shared the same name as his more illustrious father, a bona fide star in the political firmament until his death in 1935. Arthur Snr had been an iron worker by profession and ended up serving three times as leader of the Labour Party over four decades. Moreover, he was the first member of his party to hold a Cabinet position when Herbert Asquith made him president of the Board of Trade in his wartime coalition in 1915. Lloyd George then appointed him minister without portfolio when he took over as prime minister the following year. Further high office was to come when Ramsay MacDonald made him Home Secretary in 1924 after Labour came to power for the first time in its history. With Labour back in power in 1929, he next held the post of Foreign Secretary until 1931. Then, in 1934, to complete a remarkable CV, he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize ‘for his untiring struggle and his courageous efforts as Chairman of the League of Nations Disarmament Conference 1931–34’.6

It was quite an act to follow and Arthur Jnr’s career never touched quite the same heights but was nonetheless notable in its own way. In Churchill’s wartime coalition, he served as Under Secretary of State for War and, after the conflict ended, he was appointed Under Secretary of State for India and Burma ahead of India’s independence. His final government post was as Secretary of State for Air from 1947–51, with responsibility for the RAF.

While it is true that there was a strong Labour flavour to Dolphin Square early on, it was always a bipartisan sort of place. In August 1937, for instance, Lord Burghley took an apartment in Nelson House. Born David Cecil but better known as David Burghley, he was descended from William Cecil, the original Lord Burghley and Elizabeth I’s most trusted advisor. But David Burghley was better known to the British public as the Conservative MP for Peterborough and, even more so, as one of the country’s finest Olympians. His greatest moment as an athlete came when he triumphed in the 400m hurdles at the 1928 Olympics, an achievement he followed up with a slew of Empire Games titles before adding a silver medal in the 4 × 400 relay at the 1932 Olympics (having been granted time off from his parliamentary duties in order to compete).

A pivotal figure in organising the 1948 London Olympics and a stalwart of the International Olympic Committee, he was immortalised in the 1981 film Chariots of Fire as Lord Andrew Lindsay. In real life, back in 1927, he had become the first person to run around the Great Court at Trinity College, Cambridge, in the roughly forty-three seconds it takes the college clock to complete its midnight chimes (a feat traditionally attempted after the college’s matriculation dinner). The run was reimagined for the film, however, with Harold Abrahams credited with the feat. Whether Burghley ever tried a similar sprint around Dolphin Square is not recorded, although he was often observed running round the grounds to keep his fitness up.

Other eminent Conservatives included Lord and Lady Apsley. Born Allen Bathurst, Lord Apsley was an Eton and Oxford-educated military man and, since the 1920s, the Conservative MP first for Southampton and then Bristol Central with links to the air industry. Having served with distinction in the First World War, he did so again in the Second World War, when he was a colonel with the Arab Legion in Malta. He died in 1942 after the aeroplane carrying him crashed on take-off from the island. Remarkably, his wife, Violet (commonly known as Viola) then contested and won the by-election for his vacant parliamentary seat, holding it until Labour unseated her in the post-war election.

Viola was always a force to be reckoned with – a nurse and ambulance driver in the First World War, in the 1920s she had gone undercover in the Australian outback with her husband on a government fact-finding mission (and then wrote a book about it), and in 1930 she obtained her flying licence before a hunting accident rendered her unable to walk. In the 1930s, she and her husband aligned themselves with the pro-appeasement lobby and some observers detected a distinct sympathy for European fascism. Lord Apsley was a guest of Hitler at the 1936 Nuremberg Rally, while Viola was given a tour of a labour camp for the unemployed that greatly impressed her at the time. Yet when war was declared, both husband and wife threw themselves into the national effort. While he was in Malta, she headed up the women’s division of the British Legion. As an MP, she made her mark as one of very few women in a man’s world and also became a noted campaigner for disability rights. Indeed, it was the subject of her maiden speech in the House, which she delivered from her wheelchair and for which she received resounding applause. Honoured with a CBE (Commander of the Order of the British Empire) in 1952 ‘for public and social services’, she died in 1966.7

Another of the Square’s Conservative contingent was Sir Anderson Montague-Barlow, a barrister by trade and already in his seventies by the time he came to Dolphin Square. A former Minister of Labour, he was still highly regarded enough that in 1938 Neville Chamberlain asked him to head up a royal commission looking at the distribution of the industrial population – a body whose findings would prove highly influential on the post-war ‘new town’ movement. Then there was the intriguing Clementine Freeman-Mitford, a society figure who would soon marry into the political Establishment. She was a cousin to the famous Mitford Sisters, who’d variously bewitched and scandalised Britain since the 1920s as Bright Young Things whose lustre was prone to tarnish. Another of Freeman-Mitford’s cousins was Clementine Hozier, better known as Winston Churchill’s wife. Freeman-Mitford was less often to be found among the headlines than her cousins but was nonetheless close to them and was introduced to Hitler by Unity Mitford. She did not, though, develop a passion for the Führer like Unity and a few months before the outbreak of war she married the Conservative MP Alfred Beit, who by then was living in a spectacular mansion property in Kensington Palace Gardens – to which Clementine presumably moved – and had inherited one of the most spectacular private art collections in the country.

Away from political and aristocratic circles, the Square proved an attractive home to figures from the entertainment world, too. For example, Keyes House, and later Beatty House, was the home of Mr and Mrs John Jackson and, by default, headquarters of the ‘world famous’ J.W. Jackson dancing troupe. It was to Dolphin Square that hopeful applicants wrote to arrange auditions for either the Jackson Girls, the Jackson Boys or offshoots such as the Lancashire Lads. In the 1930s, these represented prized jobs for young dancers intent on carving out a career. Successful applicants might find themselves in cabaret shows, pantomimes and even on screen – the company consistently supplied venues up and down the country and had a good dose of international work too.

The Jacksons’ adverts, often to be found in The Stage, tell a tale of changing times. Where they were relatively demure in the early days, seeking dancers with expertise in tap and ballet, by the time of the company’s final advert in 1963 (Mrs Jackson had died a couple of years earlier) they were competing in a world where dancing ability was often definitely secondary to glamour. ‘All Round Good Dancers Wanted,’ John Jackson hopefully implored. ‘Any Good Girls who are free for a few weeks only may also apply.’ Positioned just next to this was a more forthright appeal for ‘Exotic Dancers’, while an additional ad on the page unapologetically sought girls for a ‘Glamour Time Floor Show’. Tap dancing not essential, it did not need to add.8

A different production company was located in Howard House, where the flat of actor-director Arthur Hardy doubled as the base for HHH Productions. This was a theatrical management company that he had founded along with fellow director-producer Sinclair Hill, and Edward Hemmerde, a barrister and Liberal MP who also fancied himself as a playwright. If they ever needed a bit of writing muscle, they need not have looked further than Collingwood House, home to the husband and wife writers Margaret Lane and Bryan Edgar Wallace. She was a successful journalist with stints at the Daily Express and Daily Mail to her name, while he was a crime novelist and occasional screenwriter whose success never quite matched up to that of his father, Edgar Wallace (who boasted career sales of his thrillers approaching 50 million copies and also had a hand in drafting the screenplay for King Kong). In fact, Margaret was writing a biography of her father-in-law when the couple moved in to Dolphin Square and barely had time to finish it before she and Bryan divorced in 1939.

She subsequently remarried, putting herself into a chain of social connections that would have seemed entirely other-worldly to the vast majority of the population but somehow was not so out of place for the Dolphin Square set. Her second husband was Francis Hastings, an artist who became the 16th Earl of Huntingdon on the death of his father in 1939 and who would later serve in Clement Attlee’s government as Parliamentary Secretary to the Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries. He had previously been married to Cristina Casati, the daughter of an Italian marquis and his artists’ muse wife, herself an heiress. Cristina in turn married Wogan Philipps, an MP for the Communist Party of Great Britain, who eventually became the only Communist Party member in the House of Lords. Philipps, meanwhile, had previously been married to the author Rosamond Lehmann, a regular of the Bloomsbury Set who subsequently took up with the poet Cecil Day-Lewis. A case, certainly, of how the other half live.

As for actors, there was the film director Henry Cass and his actor wife, Nancy Hornsby, who had some success in this period in early made-for-TV movies. Then there was Diana Hamilton, West End star and playwright, who was married to fellow actor and playwright Sutton Vane. Another aspiring actor with digs in the Square was the young Anthony Quayle, long before he found Hollywood success in movies including Lawrence of Arabia, The Eagle Has Landed and Anne of the Thousand Days (for which he would be nominated for an Oscar in 1969). He moved to Dolphin Square with his wife, Hermionne Hannen, a fine actor herself, but the marriage was not to last. Quayle signed up for military service at the outbreak of the war and the couple divorced in 1941. In 1943 he joined the Special Operations Executive (SOE), an undercover arm of the military set up in 1940 and informally known as both ‘Churchill’s Secret Army’ and the ‘Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare’. As slowly became evident over the years, he was joining what would become a long list of Dolphinites who at one time or another worked on secret operations, in espionage and in counter-espionage.

Quayle was stationed in Albania, where he was involved in various sabotage operations. An official report he posted reveals his distress at witnessing Nazi reprisals against an entire village in the aftermath of a particular SOE-guided resistance operation. He also suffered from jaundice and malaria during his few months in the country. Traumatised by his experiences, he gave expression to them in a novel in 1945, Eight Hours from England, which recounted the adventures of one Major John Overton on operations behind enemy lines in Albania in 1943.

By then, he had met his second wife – another figure who transcended the worlds of entertainment and espionage. Dorothy Hyson was American-born but made her name as a performer in England. The daughter of actors, she took her West End bow when still a child and went on to make films with star names including Robert Morley and George Formby. But she also worked as a cryptographer at the code-breaking centre at Bletchley Park, where Quayle became a frequent visitor in the war. At the time, she was still married to a different actor, Robert Douglas, but they divorced in 1945 and she married Quayle in 1947. Quayle’s first wife, Hannen, had remarried in 1943 to still another actor, Clifford Evans, who as a conscientious objector served in the Non-Combatant Corps in the war and who in later years was perhaps best known for his work with the Hammer Studios. Quayle, meanwhile, would call upon his wartime experiences for his portrayal of a special operations agent in 1961’s The Guns of Navarone.

In those very first years, arguably the most glamorous face at Dolphin Square was that of Margaret Lockwood, who was barely in her twenties when she arrived. Her star was truly in the ascendant when she appeared opposite Michael Redgrave in the 1938 British-made thriller The Lady Vanishes – the film that made Hollywood sit up and take notice of its director, Alfred Hitchcock. More success was around the corner for Lockwood, too, not least with The Wicked Lady (1945), the first British film to take £1 million at the box office.

Her life at Dolphin Square, though, was packed with its own drama. She arrived with her husband, Rupert Leon – the son of a family who had made a small fortune in the steel business – whom she’d married in 1937. Childhood sweethearts, they had wed in secret but their hopes of calm domesticity were interrupted as early as December 1938, when it was reported that Lockwood had received threatening letters from a 17-year-old, demanding: ‘It is either your £150 or your life.’9 While that case was dealt with in the courts, there were other problems closer to home. Lockwood and Leon were already beginning to drift apart, her increasing fame and success apparently putting strain upon them. A child arrived in 1941 – a daughter they referred to as Toots, who would grow up and find fame herself as Julia Lockwood.

Within months of the birth, Margaret was obliged to be back on set, Toots was sent to the country to be looked after and Leon was posted abroad with the intelligence services (he is thought to have been the first man in the ranks of the Allies to learn of Hitler’s marriage to Eva Braun, and their subsequent joint suicide). When Margaret found herself back in London, she felt increasingly isolated. Then she met an aspiring actor called Keith Dobson, with whom she embarked on an ill-advised affair. She risked a ruinous scandal, turning up at premiers in his company and even moving him into her Dolphin Square apartment. But the affair eventually ran its course. Dobson’s career never really took off and the early passion subsided. It was predictably all too much for her marriage to withstand, and after Leon returned to Britain the pair divorced in 1949.

Incidentally, in 1939 – the year after making The Lady Vanishes – Lockwood reunited on screen with Michael Redgrave to co-star in Carol Reed’s The Stars Look Down. Redgrave, by now in high demand, also starred that year in Herbert Mason’s A Window in London, in which he played a crane driver who seemingly witnesses a brutal attack through an open window on his commute. Patricia Roc, who in due course would act opposite Lockwood in The Wicked Lady, played Redgrave’s wife, who happened to be a night-time switchboard operator in … Dolphin Square. The relevant scenes were accordingly filmed in the Square itself, which duly made its silver screen bow.

The Costain family had banked on the fact that Dolphin Square would exert a pull on the great and the good. The more that big-name politicians, matinee idols and the like arrived, the greater the appeal of the Square to others. For a while, it seemed set to be every bit the urban paradise that the advertising people suggested. But just as the cinema – and, dare one say it, the Houses of Parliament – is a place of performance and illusion, it was soon apparent that Dolphin Square should not be taken at face value either. A little scratch of the surface and its dark side soon came into view.

2

THE MIRROR CRACK’D FROMSIDE TO SIDE

Despite the Costains’ dreams of creating a utopian haven in the middle of London, crime inevitably quickly came to Dolphin Square, with its tenants cast as both victims and perpetrators. Of course, there would be break-ins and bag snatches, bicycle thefts and petty thieving, muggings, drunken fisticuffs and the like. Such events are inevitable in any city setting, but some of the residents’ own brushes with the law were more spectacular. Lady Apsley and Lady Asquith’s run-ins quickly paled in comparison.

Take, for instance, the curious story from August 1939 of Harry Wells of Beatty House, who was hauled up in court for allegedly defrauding a Miss Henrietta Bennett of Kensington out of a number of Chinese antiques and artworks. It was an elaborate ruse, involving possibly entirely fictional antiques dealers in Paris, but most intriguingly, the question was raised as to whether the artworks, which included painted silks and scrolls, were not in fact indecent and obscene. When probed on the witness stand, Miss Bennett was adamant that the various female forms were merely ‘medicine figures … used by Chinese doctors’.1 There was a definite sense that Bennett was attempting, not entirely successfully, to blind the defence counsel with (Chinese medicinal) science. In any event, Wells was found guilty of defrauding her and given a six-month sentence.

A year before, it had been the turn of Hardinge Giffard, the 2nd Earl of Halsbury and owner of a flat in Nelson House, to appear in the dock. He’d succeeded to his title in 1921 on the death of his father, the 1st Earl and a man who had three times served as Lord Chancellor. The 2nd Earl had followed him into the law but in the mid-1930s swapped his wig and robes for life as a city investor. He arrived at the Square just as his new career was coming off the rails, and in March 1938 he was found against in a complex legal action centred around his various company directorships. He was then declared bankrupt the following month but by then he had fled to Paris, never to face his creditors or return to Britain again. The pitiful denouement to the story was Halsbury’s death in an internment camp in German-occupied France in 1943.

Another of the more tragic Dolphin Square miscreants in this period was Bertha Verrall, whose clashes with the law suggest she was likely her own biggest victim. Verrall was the daughter of a successful businessman and now, in her early forties, was widowed and of independent means. Having enjoyed some success as a jockey, she was focussing her energies on training horses.

Her troubles first caught the attention of the press when it was reported in 1937 that she had been fined £5 for galloping a racehorse on Rotten Row in Hyde Park, almost taking out a perambulating pensioner in the process. In December, she was at it again, this time charged with being drunk in charge of a horse in the same location. When approached by an officer, she reportedly told him, ‘I want to see my fair policeman; I like him.’ The implication was clear: Verrall was a regular offender who relied on the understanding of friendly officers. But she was not in luck that day. In court she would reveal that the horse she’d been supervising was called April 4th, a half-sister to Derby winner April 5th. The arresting officer attested to the fact that she had been riding at ‘a similar speed to what one would expect in the Derby’. But Verrall was adamant that she had not been drunk and had merely taken an odd-smelling nerve tonic. The doctor who’d examined her contradicted her, asserting she’d been ‘maudlin drunk’. A further £5 fine was decreed by the judge. Verrall cut quite a figure in the dock on that occasion, dressed in a short leopard-skin coat over a green dress, accessorised with green scarf, black hat and veil.2

It was some short time after these events that she moved into Raleigh House in Dolphin Square, but the new locale did little to bring her the stability she seems to have lacked. In October 1938, she was fined another 30s (plus 15s costs), this time for ‘riding a horse dangerously at the junction of Knightsbridge and Albert Gate on August 26th’. That day, she told the arresting officer, ‘Do not make things worse. I came very closely across. Surely that is not furious riding.’3

From then on, her offending became more serious. In July 1939 she was sued for non-payment of fees owed to a woman charged with looking after several horses. Then two months later, she was accused of threatening to cut the throats of jockey Leonard Lund’s three children. Undoubtedly an empty threat and one she claimed to have no recollection of making, it seems likely she uttered it while either under the influence or in a red mist of anger – a professional disagreement apparently behind the atrocious exchange.

It was noted at one of the 1939 trials that she was experiencing ‘bad financial circumstances’ and it was not long before she had moved out of the Square. However, her legal troubles continued – she was back in the papers when she was fined £20 for allowing suffering to a horse, then, in 1942, a further £25 penalty for similar offences. We now lose track of her as she departs the scene, unable to pay despite pawning her jewels and furs and pleading that she was ‘most awful broke’ and had been having a ‘grim time’.4

If some of Verrall’s behaviour was deeply troubling, it turned out that there was another woman living in Dolphin Square at the same time whose historical charge sheet was significantly worse. At the end of March 1937, it was reported in the newspapers that Lady Edmée Owen, resident of the Square, was embroiled in a legal case with a woman whom she accused of trying to defraud her over the sale of some furniture. Essentially, the woman had arrived at a location where Lady Owen was storing some of her property with a list of items that she had paid for, but Lady Owen held that she had expanded the list to include several items to which she was not entitled. When Lady Owen appeared at Marylebone Police Court to give her evidence, few realised that she was already very familiar with the inside of a courtroom.

Lady Owen was born Edmée Nodot in France in 1896. Leaving school at 16, she came to England with a view to learning the language and soon set herself up as a teacher. She then met Theodore Owen, a tea and rubber magnate with a family from an earlier marriage, and the couple wed in London in 1915 when she was still just 18 and he was 60. The marriage was unhappy – she was repeatedly unfaithful to him – and they went their separate ways five years later. However, seemingly in the hope of avoiding scandal, they did not formally divorce so when Owen was knighted in 1926, Edmée was able to take the title Lady Owen. By then, she had moved back to France, where she was attempting to make it in the movies as Edmée Dormeuil. Marketed as an established British starlet about to be unleashed on a lucky French public, in truth her career had amounted to little more than a few minor stage appearances in London and Oxford and a role in a 1919 film that was likely financed by her husband and which sank without trace.

A few months after his knighthood, Owen died and his estranged wife inherited his fortune. Yet for all her wealth, Owen struggled to find happiness, embarking on a series of doomed love affairs. When one dalliance came to an end in 1929, she visited a weight-loss specialist by the name of Dr Gataud, and promptly started a passionate (at least on her part) affair with him. She lavished gifts and money upon him and even feigned a pregnancy in the hope of winning his devotion, but the married doctor seems never to have intended leaving his wife for her. Just a few months into the affair, he called a halt to it. But the drama was only just beginning.

Owen purchased a gun and drank a considerable volume of alcohol before going to the doctor’s house and shooting his wife, Léonie, a total of four times. The woman survived but Owen was arrested and charged with attempted murder. Her arrival at trial raised eyebrows as, sporting a peroxide-blonde hairdo, she posed for the cameras on her way into court as if she were the film star she longed to be. It was said that she even sent invitations to journalists encouraging them to attend the trial and pleaded with the press ‘not to mention my weight gain’.

The jury found her guilty of attempted murder and Owen was imprisoned for five years, although she was free in three. She lived in Paris for a while but then returned to London, ostensibly to find some peace. But the calm she desired proved elusive. She was successfully sued in 1934 by her late husband’s two children, who claimed she had failed to provide them with their rightful inheritance. (The son’s wife, Ruth Bryan Owen, had by then been elected to the US House of Representatives and a year earlier had become the first woman to be appointed a US ambassador when President Roosevelt named her ambassador to Denmark and Iceland.) In the same year as she lost that criminal action – and perhaps not unrelated – Owen courted more controversy when she published a racy account of her life under the provocative title Flaming Sex.

She also developed a gambling habit and in November 1936 was declared bankrupt. Within just a few months, she was to be found in severely reduced circumstances, but still able to rent at Dolphin Square and chasing £20-worth of goods she claimed she’d been cheated of. How long ago it must have seemed since she was the aspiring screen siren, starring in films bankrolled by her ageing husband and, later, the heiress showering holidays, gifts and cash on a string of paramours.

Owen’s story contained strands of tragedy, but not so many as in that of 31-year-old Lynda Woods, whose life came to a premature end in her flat in Drake House in 1938. On Wednesday, 19 October she was found lying on a bed of green silk cushions, clasping a toy dog, a suicide note addressed to her father lying on a nearby table. She was dead from gas poisoning. As evidence given to the coroner would reveal, Woods was in all major respects an ordinary young woman whose life was overcome by events beyond her control. Hers was a pitiful story that spoke of the everyday secrets and the intense human dramas that are normally restrained but which sometimes erupt to devastating effect in contained communities. For Dolphin Square, it was one of the earliest sagas to propel the address into the headlines and represented a significant early dent in the estate’s veneer of respectability and contentedness.

The story was picked up by the Daily Mirror, which splashed it across the front page. The very first paragraph set the scene, hinting at a salacious subplot: ‘Lynda Woods, beautiful and mysterious dance hostess, died yesterday in a gas-filled room of her £145-a year luxury flat overlooking the Thames, after she had confessed to a friend that she was being blackmailed.’5 Here was the promise of wealth and glamour, sexuality, confidentialities, indiscretions and crime.

It would in due course emerge that the woman was the daughter of a retired army major and had attended a convent school. She had then married a shipping agent (an age gap of half a century was suggested by someone purporting to be her uncle) but was widowed in 1932. Finding herself alone in the world and in need of an income, she started working at Romano’s, a famous eatery on the Strand that, until destroyed in the Blitz, was a society institution. Before he became King Edward VII, the Prince of Wales was among its notable clientele and it appeared in fictional form in W. Somerset Maugham’s 1915 classic Of Human Bondage and in the stories of P.G. Wodehouse. The entertainments there were the stuff of legend and, in particular, it became associated with the Gaiety Girls – the chorus girls who originated at the Gaiety Theatre up the road, and who were given preferential prices when they dined there after a show.

How the young widow Woods felt about working there is not clear, although the Daily Herald described her knowingly as ‘well known in West End restaurants and night clubs’.6 We do know that until a short while before her death, she cohabited with a man at Dolphin Square who was known as Mr Woods but who was not in fact her husband. The evidence suggests that this relationship broke down and Lynda then took up with a different man of whom she was very fond. But then things had turned nasty and a former beau (presumably the enigmatic ‘Mr Woods’) threatened to share intimate correspondence with her new boyfriend if she did not pay £100.

The story of an apparently respectable life undermined was grist to the mill for the journalists telling the story. Much of the coverage adopted a suggestive tone. It was even said in some reports that she had been a dance partner and potential business partner of one Brian Sullivan, whose name had been linked to the discovery of a headless torso in Gloucestershire earlier in the year after he himself committed suicide. In that particular case, the headless victim was never conclusively identified, Sullivan’s potential involvement in the death never proven, and Woods’ connection to Sullivan only rumoured at. Nonetheless, it was used as additional colour when recounting Lynda Woods’ wretched demise.

Her death was, in truth, a sad but not entirely uncommon story. The premature culmination of a life that had not gone according to plan. The result of a delicate individual succumbing to pressures that others, and perhaps even she in different circumstances, may have weathered with comparative ease. The intervention of a vengeful former lover in a new relationship is never longed for, but more often than not it is ultimately navigated past. But her death is a motif of sorts for Dolphin Square, an early calamitous example of how the tensions between an outwardly respectable life and the potential exposure of behind-closed-doors secrets can have devastating consequences.

It is possible that the strain between public and private accounts for the mysterious death of another of the Square’s earliest female tenants – one who had a significantly higher profile than Lynda Woods. Ellen Wilkinson, or ‘Red Ellen’ as she was popularly known – both for her politics and her hair colour – was a prominent Labour MP with a firebrand reputation and a flat in Hood House. She’d been born in Manchester in 1891 into a family that understood what it was to be poor and recognised education as a path to better things. With a voracious appetite for work, she won a place for herself at her home city university and came to politically align herself with the trade unions as well as the women’s suffrage movement. The Russian Revolution was initially an inspiration to her and for a while she was a member of the Communist Party of Great Britain, before winning a seat in Parliament with the Labour Party as MP for Middlesbrough East in 1924. A stalwart of the General Strike in 1926, she came to her greatest public prominence ten years later when (as MP for Jarrow by then) she joined the Jarrow March. She was adamant that she must show support to the 200 or so people who walked almost 300 miles from Jarrow in the north-east of England down to London to protest the intolerable poverty and labour conditions that had beset the town when its major employer, a shipyard, was closed. Wilkinson was at her most brilliant, telling a crowd in Hyde Park, ‘Jarrow as a town has been murdered … What has the Government done? I do not wonder that this cabinet does not want to see us.’7

She also ventured to Spain several times in the decade to witness at first hand the impact of the civil war there, then held several junior ministerial posts under Churchill during the war. Nor could anyone accuse Wilkinson of being out of touch with the ordinary people in those years. The flat she shared in Dolphin Square with her sister Anne was bombed out twice in the Blitz.

After Attlee succeeded Churchill as prime minister in 1945, he appointed Wilkinson his Minister of Education. But her life was to end in tragic circumstances just two years later when she was discovered unconscious in her apartment on 3 February 1947. Although still only in her mid-50s, she had suffered from asthma since childhood and her health had been in a poor state for some while, exacerbated by long-term overwork and a heavy smoking habit. She had collapsed when visiting the Czechoslovak capital, Prague, the previous year, and in January 1947 she’d attended an outdoor function in Bristol that brought on a bout of pneumonia.

After she was discovered in her flat, it was determined she’d taken an overdose of barbiturates. She’d been long-term medicating to counter not only her respiratory problems but insomnia too. Taken to St Mary’s Hospital in Paddington, she died three days later on 6 February. Her death was recorded as accidental, the cause ‘heart failure following emphysema, with acute bronchitis and bronchial pneumonia, accelerated by barbiturate poisoning’.8 There was no substantial evidence to suggest that she had hoped to hasten her own death. Nonetheless, it subsequently emerged that she’d been engaged in a long-term affair with the married wartime Home Secretary Herbert Morrison, and was only reluctantly reconciled to the fact that he was unlikely ever to abandon his wife for her. In addition, there were rumours that her job was under threat in a proposed Cabinet reshuffle. What effect these additional strains placed on her already stressed physiology has been a subject of enduring conjecture.

Ellen Wilkinson’s death, dreadful of itself, was also a further link in a growing chain of events at Dolphin Square that raised as many questions as they answered. There was a sense that things went on within this citadel by the Thames that were not all they appeared. It was a reputation quickly earned and one yet to be shifted to this day, fuelling a mini-industry in conspiracy theories. Sometimes, ultimately, it is all a matter of perspective. Who can be sure when an overdose is accidental and when it’s a suicide? And who gets to judge what is a work of art and what is merely a dirty picture? In such grey areas, it is inevitable that something wholly innocent can be cast in a bad light, just as some awful things may be hidden away.

3

THE GATHERING STORM

Although the first residents moved into Dolphin Square in 1936, it was only in March 1939 that the development was reported as fully let. It would be just six months before the country was locked into another world war, but the reality was that the threat of conflict had lingered over Dolphin Square almost from the moment that people started to live there. If Fred French and then the Costains had believed a depressed economy was the greatest challenge they faced at the outset, the possibility of a second global conflict – less than two decades since the last one – cast a much longer shadow over the new community.

In March 1939, 25-year-old Miss C. Lewis, described as resident of ‘a luxury flat’ in the Square, was interviewed by the weekly John Bull magazine. She was asked her opinions on National Service and her response gives a sense of that tension between wanting to carry on as normal and preparing for what might be to come:

I want to be a woman with a career. The time I have for studying art is all too little as it is. I cannot put my name down for National Service without giving a little time to it – and, really, I can’t afford to do that. If war did come there would be emergencies no Government could contemplate at the present moment … I think there should be another National Service register, which could be signed by people to whom nothing in the present handbook appeals, but who want to serve if war should come.1