Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The Lilliput Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

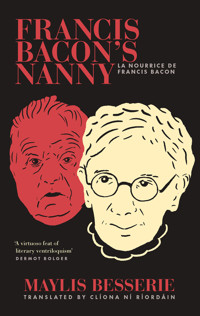

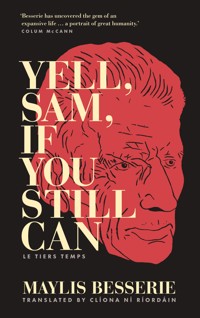

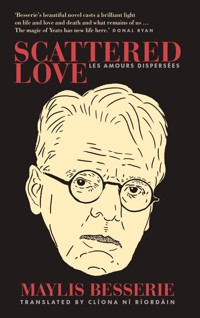

'She entered the house like a shadow … She was like a divine elixir: one drop for each of my thoughts. … I could feel the breath of the warrior, the Queen of Ireland, and it intoxicated me with the wind of hope, like noble wine.' She is Maud Gonne, the muse of writer William Butler Yeats. Yeats here returns as a ghost, having been buried in southern France in January 1939 at Roquebrune-Cap-Martin. Ten years later his remains are repatriated to Ireland. He emerges from his grave to recount his thwarted love for Maud, a story blending with the movement for Irish independence in which they each played an integral part. Yeats' ghost has suddenly appeared as diplomatic documents have come to light, casting doubt on the contents of the coffin brought back to Sligo for a state funeral. Where did the poet's body go? Does he still hover 'somewhere among the clouds above'? What remains of our loves and our deaths, if not their poetry? Maylis Besserie's exciting new work follows on from Yell, Sam, If You Still Can (Le tiers temps). In her second novel, she turns her attention from Samuel Beckett to another Irish writer, W.B. Yeats. The connection between Ireland and France is forged once again in the smithy of art, culture and the days at the end of life. A Guardian Most Anticipated Book of 2023 An Irish Times Most Anticipated Book of 2023 An Irish Independent Most Anticipated Book of 2023

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 233

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

SCATTERED LOVE

‘I bury my head in books as the ostrich does in the sand.’

–William Butler Yeats

SCATTEREDLOVE

LES AMOURS DISPERSÉES

MAYLIS BESSERIE

TRANSLATED BY CLÍONA NÍ RÍORDÁIN

THE LILLIPUT PRESS DUBLIN

To her, somewhere among the clouds above.

First published in English in 2023 by

THE LILLIPUT PRESS

62–63 Sitric Road, Arbour Hill

Dublin 7, Ireland

www.lilliputpress.ie

First edition, Les amours disperses © Editions GALLIMARD, Paris, 2023

Copyright © 2023 Maylis Besserie

Translation © 2023 Clíona Ní Ríordáin

Paperback ISBN 9781843518624

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means without the prior permission of the publisher.

A CIP record for this title is available from The British Library.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

The Lilliput Press gratefully acknowledges the financial support of the Arts Council/An Chomhairle Ealaíon.

Set in 10.25pt on 16.5pt Le Monde Livre by iota (www.iota-books.ie) Printed in Poland by Drukarnia Skleniarz

1

The coffin is so small it might be a child’s coffin. As if the old woman had lived her life in the round, as if she had come back to the beginning. Madeleine wonders if her neighbour finds the coffin too narrow, wonders if the sateen pillow was plumped up by the people in the funeral home before they laid her head on it and if she is lying comfortably there under the lid. Four men in matching suits lift the casket and hoist it easily onto their shoulders. Over the years her neighbour had become lighter and lighter, and when she died, well into her nineties, she was as lithe as a liana. She lived life to the full and died peacefully in her sleep. ‘The kind of death you wish for,’ Madeleine says to herself as she walks with the neighbour’s family behind the coffin, accompanying her to her final home. She slipped away without any pain or suffering in the early morning, which was when she usually woke up: it was a kind of false start; her eyes opened and they closed again just as quickly – and that was it. Madeleine would like to go in the same way, bowing out of the world without a whimper, but something tells her that it won’t happen like that. She imagines the pain in her left arm, the neck-breaking fall on the hard edges of the stairs, a weight like an elephant’s foot pressing down on her chest and her phone out of reach. She could put up with such an end as long as it was swift and she didn’t linger. She has already prepared for such an eventuality, already filled out the papers that never leave her wallet.

If my mental functions become permanently impaired with no likelihood of improvement, if the impairment is so severe that I do not understand what is happening to me and my physical condition means that medical treatment would be needed to keep me alive: I do not wish to be kept alive by such means. I wish medical treatment to be limited to keeping me comfortable and free from pain, and I refuse all other medical treatment.

For the funeral, she’s not sure yet. The family vault is choc-a-bloc, so if she wants to join her loved ones she will have to make herself very small – fit into an urn after being consumed by the flames. She dreads the ordeal, thinks about it sometimes and then puts it off, saying to herself, ‘There’s time enough yet.’

Her elderly neighbour had decided on the question of the last resting place without dallying – no frills, a standard ceremony, a funeral mass in Saint Joseph’s church and burial in the old cemetery of Saint-Pancrace. She departed this life in the middle of summer, her wooden coffin shining in the sunlight. She has gone to lie under the cool stone, feet towards the water, facing the mirror-like sea that saw her live out her life and grow old. An accomplished death. The old lady had been ready for several years, waiting to move on with patience, curiosity and the delectation of the believer who is waiting for paradise. Madeleine hopes that the result, whatever it is, lives up to the expectations of her beloved neighbour, who reminded Madeleine of her own grandmother. There was something in her accent, in the way she broke up the syllables as if she were biting them, adding unexpected ‘e’s and decorating them with the remains of her patois.

They reach the family vault, which welcomes them with open arms, its wide stone mouth already gaping. The old lady’s spot is on the third row, above her parents, atop the coffin of her mother, who agrees to carry her on her womb again, as if the century that had taken her away had been a mere parenthesis closed by eternity. The old woman lies next to her dead husband in the marble wedding bed, waiting for their children to come and join them one day, to complete the wooden pyramid, the strange tree formed by the stacked boxes, with the bodies of those who are no longer alive. When Madeleine comes closer to throw down her rose, she notices that the deep cavity is incredibly well organized. She had forgotten how crowded the underground city of graves is – a self-contained world, which will hold every one of them in the end.

They all march wordlessly in single file, each throwing down a rose that bounces and is lost in earth as dark as their formal wear. Madeleine adjusts the silk scarf that flows over her dress with its mother-of-pearl buttons. Her neighbour hated jeans, and, remembering she had once said that dressing properly for a funeral was the final mark of respect due to the dead, Madeleine had left hers aside. Madeleine had honoured her wishes. Thy will was done. Amen, dear friend.

During the wake Madeleine allowed herself to be served seconds; she drowned her shyness in the wine from the buffet and the cheese tarts; she endured the others’ sadness, their red-rimmed eyes. She stayed for a long time, taking the opportunity to escape her usual solitary evenings. She returned home quite tipsy. It seems to her now that a trumpet is blowing a hail of crochets in her sleep, a deluge of notes that chime with each intake of breath and nip at her heart, carrying her off into the last moments of the night. The trumpet tune makes her mind wander, soar into the heights. Then slowly it fades away. Becomes a whisper. Yields to a completely different sound.

[Radio]

Good morning, everyone, welcome. It’s seven o’clock on Tuesday, 21 July 2015, and these are today’s headlines …

Madeleine is so familiar with the voice – the way it emphasizes the first syllables and speeds up at the end of sentences, the way it laughs and clears its throat – she is so familiar with it that she does not wake up. She allows the warm, comforting voice of the merman to caress her; he is her bodiless lover who comes to sing under her window every day. The noise he makes soothes her back into a dozy state. Another old woman – not her neighbour but Jeanne, her own grandmother – valiantly uses her arms to pull herself out of her coffin, puts one leg and then the other over the side and hops out. She has come back from the dead, and she raises her arms in a victorious fashion; her grandmother looks at her and cheerfully announces that she has been reincarnated. ‘Really?’ ‘You can see for yourself.’ She is younger than when she died, Madeleine says to herself, barely eighty years old, and her grandmother does seem completely rejuvenated, even playful; she gambols around like a mountain goat, dressed in an old-style peasant dress and a brightly coloured hooded cape, under which her white legs jiggle. She hops around on tiptoe in her boots, with a basket in her hand, like a silver-haired Little Red Riding Hood, her wrinkled cheeks flushed pink as she walks. The path she is walking along winds down a verdant mountain covered in greenery. Her grandmother picks four-leaf clovers for good luck, to keep misfortune at bay.

Madeleine knows what she is about. Neither she nor her grandmother has been spared. Their loved ones fell like flies, in the prime of their lives, as if they were not meant for this world. Madeleine’s mother didn’t escape the curse; she passed away shortly after Madeleine’s birth and joined the crowd of uncles, aunts and young people in the family vault. Was it because they were short of four-leaf clovers or rabbit’s feet? All Madeleine knows is that they died, one after the other, before she had time to get to know them. Only her grandmother, the invincible Jeanne, lived on, taking on all the roles, stepping into the shoes of all those who had disappeared, watching over Madeleine until she left the nest. And even beyond. The curse hung over both of them, like a raven with its talons outstretched, ready to land on them at any time. Although they have been spared for the moment – her grandmother lived until she was nearly a hundred, and she herself is unharmed thus far – the curse has nevertheless managed to cast a shadow over their lives, covering them with a veil that sways in the breeze but always returns to its place. The question, ‘Granny, would you like a four-leaf clover?’, to provide her with an extra dose of good luck, is easily understood. In the dream, Madeleine gives her granny bunches of clover with long stems wrapped around her arthritic fingers, leaving the leaves sticking out above them like rings. Madeleine thanks her, tries to kiss her grandmother and grabs her arm. It is motionless and so thin that the bones protrude under her skin. Her grandmother doesn’t react or even look at her anymore; her bright eyes are staring blankly, mirroring the green of the surrounding countryside. When Madeleine’s lips reach her granny’s hollow cheek, the deathly cold of her cheekbone transfixes her, and all of a sudden she wakes up.

[Radio]

We end this edition with an astonishing story of a mystery at Roquebrune.

Sixty-seven years ago, the body of the Nobel Prizewinning poet William Butler Yeats was brought home to be buried in Sligo, Ireland. Well, it appears that his body never left France. At least if documents discovered by Daniel Paris, a diplomat’s son, are to be believed. In 1939, Yeats’s body was buried in the old cemetery at Roquebrune-Cap-Martin while waiting to be transported back to his native country. However, with the outbreak of the Second World War the journey was out of the question. Finally, in 1948, Ireland asked for the poet’s body to be returned. The problem was that the body had been thrown into a mass grave, making it impossible to identify his remains among the bones of all the other people interred in the grave. The documents found today bear witness to a major diplomatic incident. Who is buried in Drumcliff Cemetery, in the grave visited each year by poetry fans from all over the world? Has Yeats remained at Roquebrune in Saint-Pancrace’s seaside cemetery? For the moment, it would appear that no investigation has been launched …

Imagine that. A mystery in the old cemetery where Madeleine was yesterday. Her neighbour is still on her mind. Was it a shaggy-dog story or a supernatural event? Why did the radio voice mention the name of her town? Such a rare event. Did a light emerge from the usually cloudless Provençal sky or, perhaps, from the damp seashore? As she stirs her hot black coffee, Madeleine imagines herself in the fog that precedes the arrival of the ghost; she can already hear the hissing of the rattlesnake in the night, the cawing of the crow and the squealing of the rat. From her vantage point, she can see the darkness dissipate to reveal the glistening face of a hardy ghost, dripping with mud, daubed with the ashes of hell. ‘Ah ha!’ She can imagine everything about the Irish poet she has never heard of. Were his final wishes flouted? Is he coming back to earth, after decades in purgatory, to exact his revenge and wreak havoc in the little town on the French Riviera? ‘Hmm.’ Unless the so-called ghost simply wants to tread the rocky ground again with his fleet feet? After all, what do we know about ghostly pleasures, about what goes on behind the sheets? The steam is whisked away by her spoon, and her coffee now looks like the swirling black dress of a widow. Madeleine downs it in one go. This graveyard story intrigues her; she starts browsing on her phone for articles, digging deep in the obscure parts of the web for traces of this celebrated secret, wondering what spider could have tied the poet up with its thread for so long. Her fingers probe the screen frantically, as if they were digging directly into the soil of Roquebrune – six feet under, to be precise. The headlines from the wire services gush out and bounce back as if from the depths of the device, all asking the same question about the death of the great poet, about the identity of the person whose remains lie in his coffin. Not a word for the others, the nameless dead, the unknown bones in the grave. Hapless afterthoughts. Unclaimed handfuls of stardust. Madeleine’s good humour is gone, driven away suddenly by a gust of anger that contorts her mouth and furrows her brow. She is incensed by what she’s reading: the mass grave was opened, and they went through the motions of choosing the remains; they helped themselves. To what purpose? To fill the coffin of a poet and send him back to Ireland? Madeleine sees men in suits giving orders in front of the open maw of the grave. She scrunches up her eyes to block out the macabre visions that have suddenly appeared at her table – a gaping hole, torn flesh, tattered clothes, scattered bones. Like many inhabitants of Roquebrune, Madeleine also has a deceased relative in the grave, a stillborn ancestor, a skeleton in the cupboard – whom she often thinks of without really knowing why; the story slipped between the slats, into the pits of family memory. What happened to that body, to those remains and to the remains of the others scattered in the common grave? Are those ordinary souls of no interest to anyone? Have their bodies been desecrated to serve as understudies in the poet’s coffin? Madeleine feels that her rage is opening a deep wound that has been passed on to her like a birthmark. The ragged stitches of the wound give way, one by one, as her body swells with disgust and rage. Yes, she wants to know the answer. Her whole being wants to know what happened. What happened to her relative’s dead body, and to all the other dead bodies in the pit? She refuses to accept that they have been buried and forgotten once again. She will not be alone in defending their rights. She will bring together all the living descendants of these post-mortem victims if necessary. All those who are collateral damage.

William

The prophecy is still there, hanging in the clouds, the prophecy of the enchantress who guided my verses. Who drew up my chart. Blavatsky’s prophecy hovers above me, six feet above my cloud, her voice whirling. Her voice is like a stream that lifts the stones. The invisible masters lend their words to the enchantress. They speak through her, our ancestors, our forefathers. They all tell the same story. The story of Maud Gonne, the woman who guided my dreams, who bound me tight in her nets, who still holds me captive on my cloud. It’s not over yet. I drink the words of the woman who sees. They take me back to my beloved, my love has not disappeared, it still vibrates in the voice of the oracle. Maud has not gone.

‘Drink your coffee, William, and don’t forget to leave some grounds at the bottom. Once you finish it, I’ll turn the cup upside down, tip it onto the saucer as if it were a lid and let the universe reveal itself. Sometimes it sticks to the saucer, they say it’s the “prophet’s coffee cup” and there’s no need to separate them. You know all your wishes will come true. Are you ready? Look, the black slime has dissipated. Everything is there before you. All you have to do is read it.

‘You are going to be like an eagle with its hands twisted, standing with its beak. On this eagle, there is a “V”. On the front of its beak. Do you see it, William? If you see it, it means you are a seer, only seers and painters see. It’s the “V” of victory. You will emerge from this trial and come out triumphant, like him, like the eagle. Look at the bird, you can see its chest. Someone is hiding under its chest. See that figure sticking its head under the bird’s neck? That is you. You are sheltered by the bird, a noble bird, an eagle.

‘Next to you, a knot is being untied. Can you see the white knot? Something in your life has suddenly become undone. It is still unravelling. Look closely at the cup, there is an unravelled ribbon. It is wrinkled. There is one last knot. A tiny one. It must be untied, William. Without question.

‘Follow the powder, against the knot, I see a tooth. A tooth that was pulled. That was hurting you. The tooth was pulled out, the pain is gone. A very old pain. The burden of your ancestors, tied up in your jaw. It was a prisoner in your mouth. Sing the song of your ancestors, William. It must come out.

‘Look, it’s a bird, a golden bird – the coffee grounds are lighter, can you see? It’s a bird with a long tail. Like a blackbird or a crane. This is good news. A good omen. The omen is near. It is at hand. It is there, under your house.

‘Look closely at that spot in the cup and see the long woman with curls that curl around her face. The woman is standing. You can see her completely clearly, that’s rare – you can see she is determined, ready to listen to the secrets of the stones. The stones know. They crack open to let in the man who whispers; he is invisible. He is you, William. You are the shade of that woman in the stone. A shade that visits her, that surrounds her like a fog. You are all around her. Invisible but palpable. Look at the coffee grounds in the cup, you are hidden behind those stones. Stuck in the rock. Without her, without that woman, you can’t get out. Without the standing woman, nothing is possible. You are bound together like the souls of the dead. Look at the white path that goes from you to her on the cup. It is a cycle: she breathes your dreams into you, and you spread them under her feet. You must listen to her. Allow your dreams to flow on her back, become the boat that carries souls down the river, float and let the waves carry you to the top of the cup.

‘At the top, a big fish is waiting for you, William. Waiting for her too. A beautiful fish, a big one. It looks like a salmon. Can you see it? Can you see its eye? The fish is money. For you, it’s a treasure. A treasure waiting at the bottom of the cup. Hidden in the crashing waves. In the ebb and flow.

‘And what you see there, the triangle is a winged triangle on the tail of the fish. A winged triangle, which will show you how the wind is blowing. It will guide you on your journey. It will lead you to your destiny. To this fish. Look, it’s huge. It has spots. I don’t know what it is. A huge fish. Maybe a pike? William, this treasure is for you.

‘Now, look at the bottom of the cup. You must learn to read it, William. Follow the line, along the wall. Don’t let go. Let your eyes glide over the porcelain. It leads you to the seahorse that is hidden under the powder. A toothed seahorse. You’ll land on its back. A stroke of luck, a charm. And next to the seahorse, a white surface, do you see it? A white surface with small rocks sticking out – one, two, three, you have to jump on them to get across. This means that the path is opening. Take small steps and it will open up. Every week you will get new information, and every week you will learn something different. The road is opening up little by little. Bit by bit. Take little leaps, little leaps, and you will reach the cove, you will settle down like the bird sitting in its nest. Look how well the bird perches on the cup. You’ll be like him, William.

‘Remember, you are the man protected by the rock. But before you can reach the fish, before you can be like the bird, there are the rocks. And in the background? I can see a lion. A lion at the bottom of your cup, William. A lion with a man’s head. A head that turns around to look at the past.

2

SOUTHERN ENTRANCE TO SAINT-PANCRACE CEMETERY

ROQUEBRUNE-CAP-MARTIN

2708–2846 PROMENADE DE LA 1ère DIVISION FRANÇAISE LIBRE

OPENING TIME: 8.30 AM

CLOSING TIME: 5 PM

TEL. CARETAKER: 06.53.85.48.76

At this hour of the day, the cemetery is open; the camera is on; the chain is coiled around the foot of the gate like a snake. The sky diffuses the soft colours of the setting sun; the evening breeze is strong, blowing the sixty-year-old’s hardy frame towards the entrance. He left his cobbler’s shop early to arrive ahead of the others and parked in front of the cemetery. Now he is opening the boot, unloading the table and chairs and taking out the documents for the meeting. He has organized everything – told the caretaker about their initiative, explained why half a dozen men and women would be arriving at the old cemetery to wander among their silent ancestors, where the crosses and the graves will stare back at them. The good-humoured caretaker with the twinkly eyes had no objections. He saw no problem in allowing the group into the place of rest over which he keeps watch, as long as they showed respect for their dusty neighbours, the residents of the floor below.

Everything goes according to plan. It all starts where it all began – in the cemetery. Set on a hillside high above the old town, it slopes down unimpeded to meet the sea that lies in front of it. The cobbler follows the winding vertical path that heads straight for the shore. He glides down the endless grey stone steps, holding tightly to the black handrail that splits the cemetery in two, creating a border between the terraces, where the oldest graves in the city lie, and the rest of the tombs. He contemplates the spectacle of the strange, ongoing marriage of beauty and death – the grace of the trees that line the water, their tops colliding with the flinty stones. He walks through the alleys, his grey hair buffeted by the wind, until his legs tire, forcing him to stop for a moment. The grave made of concrete at his feet is strange – it makes him think of an iceberg, an island half-sunken into the ground. At its centre is a cube-shaped stele, like the head of a body whose legs are imprisoned in the ground. Poking out of the darkness, the tomb displays brightly coloured inscriptions, which it flings at the sky of Provence:

HERE LIES CHARLES ÉDOUARD JEANNERET

KNOWN AS LE CORBUSIER

BORN 6 OCTOBER 1887

DIED 27 AUGUST 1965

IN ROQUEBRUNE-CAP-MARTIN

Small stones have been placed on the grave by visitors, admirers of the architect who was swept away by the waves to die in the arms of the Mediterranean Sea. He had lovingly designed the grave himself, ahead of the day when he and his wife would be no more, when their dwelling place would become narrower and darker, when space would no longer matter. His heart gave out, ruptured as he dove into the sea, in that heady jump that precedes a swim. His body sank to the bottom before rising again above the sea, on the mountain that carries the graves on its back like a camel carries its humps. The cobbler is not entirely convinced by the aesthetics of the monument. It stands out from the others, especially the walls that house the funeral recesses – those vertical tombs, superimposed on each other through lack of space, their engraved plaques lined up vertically like so many solicitors’ offices. He resumes his walk; feels, through his rubber soles, the gravel that covers the dry earth; mulls over the names he deciphers along the way: painters, decorated Resistance fighters, poets and Russian duchesses – all the great and the good covered by the soil of Saint-Pancrace.

In the distance he can see the shadows of others arriving, people who like himself have responded to Madeleine’s invitation on social media; they join him, sitting around the table on the folding chairs he has just set up. As he arrives, one of them, the youngest – a beanpole of a man with a waxy complexion and tattoos showing under his T-shirt – congratulates him on the little spot he has found at the back of the cemetery, under the tall pine trees. Their small talk – ‘You can’t say the neighbours are noisy’ – does not reflect the emotion they feel today. The cemetery, where the first grave was dug nearly two centuries ago, has been marked by too many wars; saturated with memories and silence, it crushes them with its loftiness, with the splendour of its stones, with nature and the sea that surrounds it. They all know what brings them together today: weighed down by painful family history, they all fear that one of their relatives – a grandfather, an aunt or a cousin – may have been sent to Ireland to be buried instead of the poet. They are all determined to retrieve their dead.

Each has started the investigation by themselves, asking those around them, questioning their immediate families, sharing what they found with the group. Today, on the advice of a lawyer, the group is going to set up an association. Their aim is to build a case, by gathering evidence, so as to start proceedings and obtain the analysis of the remains transported to Ireland. They will demand the truth.

Madeleine has filleted the documents published by the press, the letters from embassies, the reports that miraculously appeared out of the safe. She has written to Daniel Paris, the man who discovered them. He has kindly agreed to meet her in Paris next week.

On this day, 18 September 2015, in the old cemetery of Saint-Pancrace, the association of ‘The Scattered’ gains legal status. And as this is happening, a bird, probably a peregrine falcon, flaps its speckled wings in the particle-laden air. The bird flies over the wall and lands on the stele erected in memory of the poet’s brief sojourn in the cemetery. Its talons cover a winged unicorn, caught in mid-air, under which is written, ‘William Butler Yeats 1865–1939’.