Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The Lilliput Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

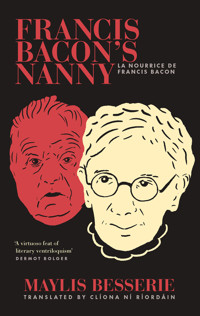

This novel by Maylis Besserie, the first of her Irish trilogy, shows us Samuel Beckett at the end of his life in 1989, living in Le Tiers-Temps retirement home. It is as if Beckett has come to live in one of his own stage productions, peopled with strange, unhinged individuals, waiting for the end of days. Yell, Sam, If You Still Can is filled with voices. From diary notes to clinical reports to daily menus, cool medical voices provide a counterpoint to Beckett himself, who reflects on his increasingly fragile existence. He remains playful, rueful, and aware of the dramatic irony that has brought him to live in the room next door to Winnie, surrounded by grotesques like Hamm or Lucky, abandoned by his wife Suzanne who died before him. Besserie delights in Beckett's bilingualism and plays back and forth between the francophone and anglophone properties of language, summoning James Joyce as Beckett reminisces about evenings the two spent together singing, talking and drinking. Largely written in the library of the Centre Culturel Irlandais, Besserie has kept the hum of Irish voices throughout this work. Yell, Sam, If You Still Can won the "Goncourt du premier roman", the prestigious French literary prize for first time novelists, just before the country went into lockdown. Besserie is now planning a further two novels that will explore the links between Ireland and France and is touted as the new star of the French literary world. Financial Times Book of the Year 2022

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 199

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

YELL, SAM, IF YOU STILL CAN

Only one Marguerite in the yard. This is for her.

YELL, SAM, IF YOU STILL CAN

LE TIERS TEMPS

MAYLIS BESSERIE

TRANSLATED BY CLÍONA NÍ RÍORDÁIN

THE LILLIPUT PRESS DUBLIN

First published in English in 2022 by

THE LILLIPUT PRESS

62–63 Sitric Road, Arbour Hill

Dublin 7, Ireland

www.lilliputpress.ie

First edition, Le Tiers Temps © Editions GALLIMARD, Paris, 2020

Copyright © 2022 Maylis Besserie

Translation © 2022 Clíona Ní Ríordáin

Paperback ISBN 9781843518341 eISBN9781843518464

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means without the prior permission of the publisher.

A CIP record for this title is available from The British Library.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

The Lilliput Press gratefully acknowledges the financial support of the Arts Council/An Chomhairle Ealaíon.

Set in 10.25pt on 16.5pt Le Monde Livre by iota (www.iota-books.ie) Printed in Kerry by Walsh Colour Print

ACT ONE

Le Tiers-Temps, Residence for Senior Citizens, Paris

25 July 1989

She is dead. I have to remind myself constantly – Suzanne is not in the bedroom. She is not with me. She is no longer present. She is … buried. Yet, this morning, when I was under my old blankets, it felt as if she were here, buried under the blankets with me, and not dead. Here, huddled up against her old Sam. As a matter of fact, it is only because she is here, leaning against my old bones, stretched lengthways against my carcass, that I know that I’m not underground myself.

I’m a little cold all the same. I’m all skin and bone. My mother was forever telling me that. When I was a child, I ran all the time, in the streets, in the fields. I ran to keep myself warm because I was skin and bone. I ran so that I didn’t have to listen to May telling me that I was all skin and bone. I ran. One day, I ran for such a long time that I really ran away. Ran off and escaped over sea. Ran far away from May.

Suzanne ran alongside me for a long time. Through the forest, on the dead wet leaves, over the roots buried deep beneath the trees. We ran with the wind at our backs, pushing us further and further into the night. We were afraid of our feet rustling in the leaves under our weight. So, we ran ever faster, we ran scared. Suzanne’s feet hurt but she ran all the same. The brambles pricked us. My feet beat against the ground, I could feel my heart racing, like Suzanne’s. Suzanne was clutching at my shoulders, at my overcoat, she was hanging on to me, wanting me to lift her feet that were weary from the weight of the earth. The earth was like a load she was carrying, like lead, so heavy it would split your soles.

I couldn’t feel my feet any more. I ran for me and for Suzanne. One foot for each of us. Lifting them out of fear. She had pulled me along for so long, she was exhausted, dead on her feet. Suzanne is dead. She is not in the bedroom. She has let go of my overcoat. Suzanne has left me.

I’m cold under the blankets. Today is Friday, I think. The only thing I can see from my bed is a plucked plane tree. In Dublin, I could hear the gulls’ cries. The city belongs to them and they hoot and squawk – at every door. They surround the towers in Sandycove and fly in flocks right into the centre of town. Squealing. Eating everything they find. They’re a sight to behold, like predators on the prowl. I can see myself in Ireland, picking up the pace. My swift shadow reflected in the Liffey, the gulls snapping at my heels. I thought the noise was my knees knocking together, but it was only the sound of my soles clacking on the grey stones. Later, when I used to come to see May (to see my mother), the gulls had grown fatter again. They knocked off the leftovers from the boats travelling on the Liffey. They guzzled the leftovers left in the bins – they stole from the poor; they ate the leftovers and even the poor themselves.

On Rue Dumoncel, I cannot hear the gulls. I cannot even hear Suzanne. I cannot hear anything any more. I can only hear what I have already heard.

I’m cold under the blankets. I need to think of a song.

Bid adieu, adieu, adieu,

Bid adieu to girlish days.

The voice of Joyce. It warms my heart. The voice of Joyce under my old blankets. He makes music even when he writes. His feet flit from one piano pedal to the other. Joyce plays and sings with a Cork accent. His father’s accent. He still has quite a good tenor voice. He sings for his friends – the Jolas, the Gilberts, the Léons; he sings for Nino. I’m under the table, under the weather, listening to him. The house shakes, a girl dances. Joyce’s daughter, Lucia. I close my eyes. When Joyce stops the show, he gets up on his three feet – his own feet and his walking stick. He bows and then, at once, asks for a drink. He is Irish.

I used to drink in Grogan’s, on South William Street. I would meet my friend Geoffrey there, Geoffrey Thompson. He was always flanked by a number of acolytes leaning on the counter. I would meet him and we would have a drink together. In winter, I can remember customers leaning on the counter, like sparrows on a wire. They used to put their caps and hats down next to their drinks to make themselves comfortable. I like Grogan’s. The wooden floors and panelling, the rays of blue and orange light when the sun shines through the stained-glass windows. I remember that all of the customers would be dressed the same – white shirts, buttoned waistcoats, black jackets and shoes. Geoffrey had a moustache. A thick moustache that dripped when he drank. In the pub, he used to have his happy evening air. Geoffrey is good company. In Ireland, men crack jokes without daring to look each other in the eye. They are funny and shy. They are funny but the humour doesn’t reach their eyes. They look into the distance when they tell a joke. They stare at the clean glasses on the shelves, or at the pint glasses, stained with traces of foam. In Dublin, everything is intimidating and everything is banned. I left, ran away.

MEDICAL FILE

File number: 835689

Mr Samuel Barclay Beckett

Age: 83

Height: 1.82m (6 feet)

Weight: 63 kg (9.9 stone)

Section 1

The patient is an 83-year-old writer, referred by his friend, Dr Sergent, for emphysema and multiple falls resulting in losses of consciousness.

There is a history of Parkinson’s disease on Mr Beckett’s maternal side.

On 27 July 1988, his wife found him unconscious on the kitchen floor. He was admitted to the hospital in Courbevoie, where tests showed no evidence of fractures and no internal bleeding. He was subsequently transferred to the Hôpital Pasteur in order to investigate the cause of his falls.

At present, he displays none of the three classic symptoms of Parkinson’s disease: resting tremor, bradykinesia (akinesia), extrapyramidal rigidity. However, the typical motor symptoms (muscular rigidity and postural instability) have led the neurological team at the hospital to suspect that he may be suffering from an atypical or associated form of the disease.

The patient also says that he finds it increasingly difficult to write (dysgraphia) and to hold his pen.

In light of his ‘fragile’ physical state, it was recommended that he should move into a medicalized retirement home.

He has been living in Le Tiers-Temps retirement home since 3 August 1988. His wife has since died. He was seriously malnourished on arrival. The high-calorie diet, parenteral nutrition and high-flow oxygen therapy have improved his state. He has been allowed out of the residence for solo walks in dry weather, when he feels able to do so.

NURSING NOTES ON MR BECKETT

Nadja, nurse:

Mr Beckett adheres strictly to his daily routine. He writes in the evening and gets up late. I usually go into his room at the end of my rounds, at about 9.45 or 10 am, so that I don’t disturb him.

He is not on a drip, and can wash and dress himself unaided.

He is a very quiet patient, and is polite to staff.

At his own request, he eats his meals in his room and does not participate in the activities organized for residents.

When he feels capable, he leaves the residence at the beginning of the afternoon to go for a fifteen-to twenty-minute walk, as recommended by his physiotherapist. People come to visit him at the end of the afternoon. He drinks a little alcohol and continues to smoke.

Treatment:

– High-calorie diet administered orally until his weight returns to within normal range.

– Oxygen therapy via face mask, at one to two litres per minute.

Le Tiers-Temps, Residence for Senior Citizens, Paris

26 July 1989

I’m in the garden. I’m not sure if it can really be called a garden, but I’m ‘in the garden’. That’s what they call it here. I’ll use its given name. In the garden, the lawn is made out of green, non-slip plastic. It’s a fake lawn and you walk on it as if it were real, and yet it’s not because you can’t lie down on it. And that’s how I come to be in the garden.

I’m not very steady on my feet this morning. The man who comes every morning to get me to exercise my legs said: ‘Mr Beckett, you’re not very steady on your feet this morning.’ I did my exercises all the same. I did them as best I could. I raised my leg and set it down again. I did it again and again, as often as he asked. I did the same with the other one. With the other one, it’s a bit harder. I lift it, or at least I try to: I grit my teeth, but my leg doesn’t co-operate. I lift it all the same and I set it down again. I fail and I try again. All the same, I manage to walk. Well, walk is a bit of an exaggeration. I push one leg, and move it, so it ends up a couple of centimetres in front of the other. My feet move at a snail’s pace and work at walking, but they’re not working that well.

There’s a strip of fake grass next to the wall. A strip of lawn. That’s where I walk, when I’m not very steady. Some days, Nadja, the nurse, walks on the strip of lawn with me. Her hair is shiny; she must put some sort of perfumed hair oil on it. I can smell the oil when she takes my arm, as if I were her elderly husband. I can feel her as she brushes against my old carcass to help it move. I can feel her. What does she think when she takes my motionless arm and I look at her from behind my thick owl glasses? I don’t know. She’s doing her job. She’s kind. If I bore her she gives nothing away. I can smell her hair from a distance. I don’t go up to her – I’m ashamed of what she might feel. I keep my arm by my side, hoping she’ll take it. It doesn’t happen every day.

The wall that surrounds the garden is high. At the E.N.S. on Rue d’Ulm, there were no walls, but the railings were high. I had to climb over the railings. I hopped over them to go drinking. I drank and hopped over the railings. I hopped over and back. On the way out and on the way home. It was a less elegant hop on the way back but it was a hop all the same. I drank with my old friend Tom. Never before 5 pm. Absolutely never. At the Cochon de Lait I drank Mandarin curaçaos, Fernet-Brancas and Real-Ports. I was drunk as a lord. Even lost my glasses, stumbled and tripped, gabbing – like a hermit breaking his vow of eternal silence. A drunken idiot, a cheerful drunk. My spirit lightened by my heavy load. Light, so light-hearted. Had I only listened to my father, I could have spent happy days at Guinness’s, that radiant, flourishing brewery. Happy and hoppy. Alas, the memories come flooding back now that I’m finished. Now that I no longer know how to write. That I no longer write. Almost not at all.

I used to drink with Joyce too. In gorgeous glasses. We’d drink at nightfall, when the beasts return to the byre, huge quantities of white Fendant de Sion. Joyce converted everyone to his tipple – which reminded him of the urine of an archduchess, he used to say. Joyce converted everyone. Joyce was a real archduchess.

If anyone thinks that I amn’t divine

He’ll get no free drinks when I’m making the wine.

But I have to drink water and wish it were plain

That I make when the wine becomes water again.

Good God, this garden stinks of piss. Rivers of codgers’ piss trickling onto the fake grass. Had it been real, the grass would have turned yellow. Luckily, it’s plastic. It keeps its colour. A little rinse and it’s gone. But nothing can be done about the stench. Nothing to be done in any case.

In the garden, I’m afraid of being taken. Afraid that someone will say: Mr Beckett, I’ll give you a hand. And they’ll take my arm as if I were an elderly aunt to be promenaded around the garden. To whom they would show the flowers. Or the clouds. I tremble at the thought of being touched. That someone might touch me. I always expect the worst. Once upon a time, though, I was touched often. Peggy, for instance, touched me a lot. She touched me with gusto. She would grab hold of me like a warrior grabs the saddle of his mount before pulling himself upright on top of it. She would harpoon me with her solid hands. She would hang on to my flesh, would pull it off my bones and brandish it like a trophy. She caught hold of me with such enthusiasm. I don’t know what it meant. If it was real love. But she sank her hook in me and I liked it. I mean I let her at it. And if I let her at it I must have liked it. Of course. Liked that she hung on to me, burning my bark. Liked that she skinned me like a rabbit whose pyjama pelt is peeled off after being stunned by a heavy stone. Yes, I liked it. I liked it for a long time.

In Foxrock, there was also that girl. Her name escapes me. The girl who liked to pinch me on the train. When I boarded at the station in Glenageary, she was often there on the train. Quite pretty. In an Irish way. She would sit down beside me, a fountain of hair dripping down her back. The fine girl would pinch me with her fearsome fat fingers. The big finger and the thumb would stick into the side of my ribs, digging in with her nails. I would whinny. And that really made her laugh. I don’t remember the beginning of the story. How did she get into the habit of pinching me? I don’t know. I must have said something. Something obscene. I’d do that sometimes with strangers – I mean with women I didn’t know. I’d say obscene things and sometimes I’d be caught and even pinched. She had a devilishly good time by my side. I had such pleasure between her thighs. I pinched her and she pinched me. Peggy pinched me too. And in the end, it hurt.

PATIENT CARE LOGBOOK

26 July 1989

Sylvie, nurse’s aide (9 am–6 pm):

Up at 9.45 am. Had a cup of tea and two slices of toast for breakfast.

Washed and dressed himself.

Physiotherapy from 10 am to 10.20 am.

Had lunch in his room at 11.50 am:

– Mushroom soup

– Filet of cod with lemon, carrot purée

– Stewed blackcurrants

Ate very little. Meals augmented by high-calorie cream desserts to replace the fruit juice the patient dislikes.

Walked as far as Place d’Alésia, was out of breath on his return.

His friend Madame Fournier came to visit. Two glasses of whiskey at around 5 pm.

Nadja, nurse (6 pm–12 pm):

In high spirits at the end of the afternoon. Making joke

Dined in his room at 6.45 pm:

– Potage Polignac

– Pasta salad with ham and mushrooms

– Cream cheese with herbs

– Fruits of the forest pudding

Still at his desk at midnight when my shift finished.

Le Tiers-Temps, Residence for Senior Citizens, Paris

29 July 1989

I am in my room. Décor: bed, bedside locker, commode, book-shelves, mini-fridge supplied by my faithful Edith, my faithful friend. Translator beyond compare.

In front of the window, a table to write at and a cream-coloured telephone. That’s about all. The décor would have pleased my mother. It’s as gay as her own bedroom – fancy as a Protestant fantasy. This room is not really my room. This is where I am being minded. It’s where I reside and where, henceforth, I receive my post. My bed is overhung by a three-bulb light fixture suspended from the ceiling by a chain. Every time there is any movement in the upstairs rooms, it shakes and threatens to give way. Were it to do so, that would be the end. I should be so lucky! It would come crashing down and finish me off. A quick end. A happy accident. Unlikely. Not every day is filled with adventure. A couple of lines in the paper: Lighting strikes! Never before was an Irishman (he was only a shadow of himself) hammered like that. For the moment, the light is still there, hanging over my soft brain.

When I turn on the light, at around 6 pm, my room turns wild. I mean the colour. It suits the wallpaper. It sets it free. The dirty yellow becomes almost mauve or muddy brown. When I am seated at my table at around 6 pm, I gaze at the moon if the sky is cloudless. Night falls on me, as if I were by the lake in Glendalough. My father ruffles my hedgehog hair, in silence. Night falls, in silence. We look at it fall and we wait. We wait a little longer, as the light fades. That’s it, says my father. That’s it; it’s almost at an end. The pink clouds are going to disappear behind the Wicklow mountains. It’s time to go home. To come down. The darkness has altered the paths. My father wraps his belt around my hand and guides me. We are two blind men in a forest. I allow myself to be pulled along by the belt. I lift my legs so I don’t stumble over the roots. The dark night links me to my father, in silence. My father is an owl in the night and the moon is all he needs.

When we return, May is raging. Frothing at the mouth. Fuming. She is always furious when she is worried. A few minutes before that, before nightfall at the edge of the lake in Glendalough, before the moon sets, May falls silent. A happy silence. The calm before the storm.

This evening the moon is reddish. My leg hurts; l lean over my table to look at the russet moon. The honey moon. I am in Joyce’s room.

‘Wait till the honeying of the lune, love!’

I am sitting across from him. A bandage covers his left eye, under his glasses. His thick round glasses. I look at him without knowing if he can see me. The elastic part of the bandage parts his hair above his temples. He stares into the distance. Perhaps at the moon. The honey moon. He is wearing an old-fashioned suit and a striped shirt with mother-of-pearl buttons. The moustache suits him. It was a good idea. It hides his lips, like the peak on a gendarme’s cap. A single line of hair connects his mouth to the base of his chin. He dictates all in one go. He crosses his legs, one under the other. I look at him and I do the same. He dictates. I don’t know if he can see me. His sight is failing and he lowers his eyes. Perhaps he can just about make out my shadow as he dictates.

We are sitting like two companions in front of the scant pages. I type. The words appear. I type quickly. There is a knock at the door. Entrez. Lucia, his much-loved daughter says hello to me. She gives a message to her father and smiles skittishly at me. She is beautiful despite her eyes. She has a squint; the alignment of her eyes is not parallel. I’m not sure if you can use the word parallel or not parallel when talking about the alignment of eyes. In any case, Lucia’s eyes are not parallel. She’s still beautiful though.

Lucia leaves Joyce’s room. I type Joyce’s book, his Work in Progress – it progresses slowly. Music of the language, of languages. I type his English that is full of Ireland. He spits out page after page, the Ireland of our mothers. The Ireland of May. It comes to life under my fingers. It’s very contagious. Transmitted by the tongue. I took a long time to be cured of it. Of Ireland, of Joyce, of May. Of Joyce, of my mother, of my tongue. Am I cured? I don’t know. There’s no denying that we are sentenced at birth – to be the sons of our fathers and mothers. To be born of them. Born of May. Far beneath Joyce. You could say that it started badly. I’m not saying that I did what it takes. No. I could certainly have done better. Taken some precautions. Or even draconian measures. Fighting evil with evil. I could have killed May, for example. Killing my mother would not have been that hard. I had a thousand opportunities to do so. All I needed was a small cushion. Hold it firmly. In silence. Just for a few minutes. May wouldn’t have suffered. Or not for long. I could have spared her such a long existence. If you think about it, it wouldn’t have been as bad as it sounds. Even for her. A happy escape.

May was a nurse. I could have taken advantage of a moment’s fatigue on the way back from a night shift in the wee small hours. I could have put an end to her suffering and to mine. No, to have done things properly I would have had to have killed her before my birth. Or in childbirth, giving birth to me, why not? That would have been ideal. A lucky birth – night and day. Of course, the best solution of all would have been if my grandmother hadn’t been born either. We would all have been nipped in the bud. That would have been the simplest solution. But chronologically, I admit, it’s a fucking mess.