Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Luath Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

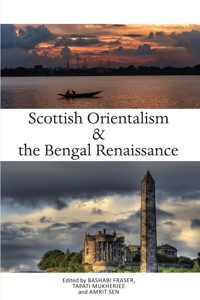

The historical relationship between Scotland and India is a relatively unexplored part of colonial history. This project seeks to re-examine the interchange of ideas initiated in the 18th century by the Scottish Enlightenment, and the ways in which these ideas were reformed and shaped to fit the changing social fabric of Scotland and India in the 19th and 20th centuries. In this volume, the significance and influence both nations had on the other is examined and brought to light for the first time. With contributions from key individuals and institutions in both Scotland and India, the range of ideas that were interchanged between the two nations will be explored in the contexts of culture studies, history, the social sciences and literature.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 343

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Rabindranath Tagore

First published in India 2017 by The Director, Granthan Vibhaga, Visva-Bharati

Revised edition first published in the UK 2018 by Luath Press

ISBN: 978-1-912147-11-3

The authors’ right to be identified as the authors of this book under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 has been asserted.

The paper used in this book is recyclable. It is made from low chlorine pulps produced in a low energy, low emission manner from renewable forests.

Printed and bound by Bell & Bain Ltd, Glasgow

Typeset in 11 point Sabon by Lapiz

Photographs (except where indicated) courtesy of the Rabindra-Bhavana Archives

© the contributors

Contents

Acknowledgements

From the West to the East

Scottish Orientalists and the Bengal Renaissance: An Introduction

BASHABI FRASER

A Sojourner’s Calcutta: Through the Colonial Lens

BASHABI FRASER

East Meets West: A Vibrant Encounter Between Indian Orthodoxy And Scottish Enlightenment

TAPATI MUKHERJEE

The Scotland-India Interaction: Scottish Impact on: A So-called Native Stalwart in India–Dwarakanath Tagore

TAPATI MUKHERJEE

The Trio who turned the Clock of Education in Bengal

Serampore Missionaries and David Hare: On the Penury of Education in Nineteenth-Century Bengal

SAPTARSHI MALLICK

Understanding the Renaissance in Nineteenth Century Bengal

KATHRYN SIMPSON

The Caledonian Legacy: Of the Scottish Church College in Kolkata

KABERI CHATTERJEE

The Poet and the East-West Encounter

A Complex Interface: Rabindranath and Burns

AMRIT SEN

An Assessment of Sir Daniel Hamilton’s Political Philosophy: The Panacea of Scottish Capitalism and Utilitarianism

THOMAS CROSBY

A Scotsman in Sriniketan

NEIL FRASER

Arthur Geddes and Sriniketan: Explaining Underdevelopment

DIKSHIT SINHA

Scientific Innovation in India

The East’s Writing Back to the West: Acharya Prafulla Chandra Ray and Postcoloniality

BISWANATH BANERJEE

The Scientist as Hero:The Fashioning of the Self in Patrick Geddes’s The Life and Work of Sir Jagadish. C. Bose (1920)

AMRIT SEN

List of Contributors

Acknowledgements

THIS BOOK IS THE outcome of a collaborative project between the Scottish Centre of Tagore Studies (ScoTs) at Edinburgh Napier University and Rabindra Bhavana at Visva-Bharati in the UK and India respectively, co-funded by the British Council and the University Grants Commission (UGC) of India as a UK India Educational Research Initiatives (UKIERI) project. We are grateful to the UKIERI for their generous research grant and support.

As a Knowledge Exchange programme, this project was an interchange of ideas and personnel with staff and research students travelling from the UK to India and vice versa to engage in intensive research in diverse areas of the research topic and participate in an intellectual interchange with colleagues and students of the partner institution. Without their participation and contribution, the research could not have been conducted, completed and brought together in this book. We are thus grateful to our research students, Kathryn Simpson and Thomas Crosby for travelling from Edinburgh Napier University to Visva-Bharati and consulting the Rabindra-Bhavana archives and library, investigating various materials in different Indian archives and libraries and consulting leading intellectuals for their respective chapters. We have benefitted from the work of our Indian research students, Biswanath Banerjee and Saptarshi Mallick, who have made research trips to the UK to do dedicated research in UK libraries and archives for writing their contributory chapters for this book.

At seminars held as part of this UKIERI project at Visva-Bharati and Edinburgh, several scholars have interacted with the researchers on the research theme and contributed to the scholarly debate that has informed this book. We are thus thankful to Rosinka Chaudhuri (Institute of Social Science, Kolkata), Mary Ellis Gibson and Nigel Leask (Glasgow University), Roger Jeffery, Crispin Bates (University of Edinburgh), Friederike Voigt (National Museum of Scotland), Aya Ikegami (the Open University) and Murdo Macdonald (Dundee University) for their incisive comments and reflections which have enriched the project. We value the contribution of Dikshit Sinha (Sriniketan, Visva-Bharati) in a significant chapter to this volume.

Tom Kane (Edinburgh Napier University) was involved in advancing the research at the Rabindra Bhavana archives and at institutions in and around Santiniketan and in Kolkata to assess the educational links between Scotland and India, which have enriched this research project. Christine Kupfer (Edinburgh Napier University), conducted workshops in Scotland to assess the current relevance and efficacy of Rabindranath Tagore’s ideas on education in school classrooms in Scotland, which have proved useful for researchers contributing to this book. We value the work of Kaberi Chatterjee who has travelled to Scotland to follow the trail of Alexander Duff and pour over relevant records in libraries and archives in the UK for her specific subject.

The Special Advisor for this book is Neil Fraser (University of Edinburgh) whose dedicated research in both countries and intellectual advice have proved invaluable for this book. He too, like Dikshit Sinha, has brought his social scientist’s evaluation of Rabindranath’s pragmatic projects in a chapter for the book.

This book would not have been possible without the generous help and co-operation of the staff at the Nehru Museum Library and Archives (Delhi) , the Sahitya Akademi Library (Delhi), the National Library of India (Kolkata), the Victoria Memorial Library and Archives (Kolkata), Goethal’s Library and Archives (Kolkata), Asiatic Society Library and Archives (Kolkata), Bishop’s College Library and Archives (Kolkata) and Scottish Church College Library and Archives (Kolkata) in India. In the UK, our project members are deeply grateful to the knowledge, advice and support of staff members of the National Library of Scotland, University of Edinburgh Library, Stathclyde University Archives, Dundee University Archives, St Andrews University Library and Archives, the Devon Record Office (for Elmhirst’s papers from the Dartington Trust) and the India Office Library at the British Library.

This project has benefitted from the rich collections at the Rabindra Bhavana Library and Archives at Visva-Bharati and the Tagore Collection at the Scottish Centre of Tagore Studies at Edinburgh Napier University. We owe the Tagore Collection largely to the generous donation of William Radice and Indra Nath Choudhuri.

We would like to express our deep gratitude to Utpal Mitra who made many of the resources at the Rabindra Bhavana Archives available to us, to Madhumita Roy for her dedication and help with formatting the chapters and to Priyabrata Roy for his technological help in expertly typesetting the manuscript. He has done a brilliant job. A special thanks to Saptarshi Mallick who has not only been an excellent researcher, but has always been there to assist the team members in multiple ways, including locating relevant documents and providing expert technical help. He has been our invaluable trouble-shooter.

Since this was a Knowledge Exchange project, it involved the travel and stay of researchers from one country to the other. As such, it required meticulous planning and administrative support to ensure accommodation, subsistence overseas and internal travel arrangements for which we are sincerely grateful to the staff of Ratan Kuthi and Purba Palli Guest House at Santiniketan and Debjani and Kamal Sharma in Kolkata for making our research members welcome and comfortable in their guest flat. We would like to specially thank Marguerite Le Riche, the Administrator of our Research Centre, the Scottish Centre for Tagore Studies (SCOTS, under CLAW) for her continuous help with making travel and accommodation arrangements for our research partners in the UK and the smooth administration of the entire UKIERI project. Our research work in Delhi was made possible by Indra Nath and Usha Chaudhuri, who not only provided warm hospitality in their home, but made all the arrangements to facilitate our library work and meetings with key intellectuals who could advise on our project. It is not possible to name all those who have helped us directly and indirectly during the research period. This book would not have seen completion without the co-operation and support of our colleagues at Edinburgh Napier University and at Visva-Bharati who let us have the space and time to devote to the research for this book. Thanks also to our friends in Visva-Bharati who have gone out of their way to help all the researchers on this project.

We would like to thank Prof Swapan Kumar Datta, Vice Chancellor, Visva-Bharati and the Registrar, Prof Amit Hazra and the Director of the School of Arts and Creative Industries, Edinburgh Napier University, Pauline Miller Judd for their administrative support for the project and the book.

We appreciate the British Council’s permission to use a part of our funding towards publication costs of this book.

We are grateful to Gavin MacDougall, the Director of Luath Press (Edinburgh) and to Visva-Bharati Press for agreeing to publish Scottish Orientalism and the Bengal Renaissance: the Continuum of Ideas in the UK and India, respectively, bringing the ideas, thought and work of two great men on education and the environment to a global audience.

Tapati Mukherjee

Bashabi Fraser

Amrit Sen

Santiniketan

From the West to the East

Raja Rammohan Roy

Scottish Orientalists and the Bengal Renaissance: An Introduction

Bashabi Fraser

THIS BOOK CONSIDERS the work of Scottish Orientalists who are significant in Indian history, having contributed to India’s socio-cultural developments. The intention is to understand their special significance within the context of British Orientalism. This study is not about the emergence and history of the Bengal Renaissance per se, but about the impetus prominent Scottish Orientalists lent to the tide that changed Bengal/India and propelled her on this unstoppable crest into the modern era. The Indo-Scottish interface generated a continuum of ideas as evident in the work of Bengal Renaissance figures who worked closely with Scottish Orientalists, effecting the transformation of the socio-cultural fabric of Bengal through the implementation of their epoch changing ideas in a period of creative transition.

In order to gauge the special approach of Scottish Orientalists in and to India, it is necessary to go back to the significance of the ideas generated during the Scottish Enlightenment in the 18th century which were reinterpreted and reshaped by Scottish Orientalists, the legatees of the Scottish Enlightenment, who contributed to the socio-cultural, religious and literary debates that affected the social reality and ideology of the times in Scotland and India from around the mid-19th century to the 1930s. Jane Rendall has said ‘the extent to which the Scottish Enlightenment offered a conceptual framework for the understanding of complex and alien Asian societies has been underestimated’ (Rendall ‘Scottish Orientalism from Robertson’ 69). This introductory chapter thus addresses and assesses this hitherto largely unexplored field and considers the socio-historic significance of the debates that were generated in the discourse that inspired and informed the Bengal/Indian Renaissance Movement. The prevailing debates emanating from Scottish Orientalists in India will be considered, inasmuch as they affected and informed the wave of change influenced by certain Scots whose interventions affected religious thinking, education and Bengali society, which would affect India as the nationalist consciousness gained momentum.

For the purposes of this study, we will first look at the major ideas that were established during the period of the Scottish Enlightenment on which later modernity is based (The Scottish Enlightenment: The Scots’ Invention of the Modern World). The Act of Union in 1707 gave Scotland the opportunity to work within, and benefit from, the British colonial enterprise. They did pay higher taxes but gained from a better governance. The Scottish Reformation (1638) introduced an egalitarian democratic spirit to Scottish culture with the setting up of Scottish Presbyterianism, followed at the end of that century by instituting schools in every parish. The Scottish idea of history then became important as it was fundamentally based on the idea of progress.

The Scottish Enlightenment presented man as the product of history and a creature of his environment. It shared with the broad spirit of the European Enlightenment the thirst for knowledge and the willingness to challenge dogmas. Scottish Universities, at this time, played a key role in framing and generating transformative ideas. Scots invented the social sciences and the establishment of different branches of learning into disciplines; Edinburgh and Glasgow were the vanguard of bringing new disciplines into universities.

Moving away from the Hobbesian moral law and view of life being ‘nasty, brutish and short’ for the majority (and that power corrupts and absolute power corrupts absolutely), Scottish intellectuals were influenced by the Scottish philosopher, Francis Hutcheson (1694–1746). Hutcheson believed that people are born with an innate moral sense of what is right and wrong, that man is not inherently selfish and his search for personal and public happiness is justified from this sense of moral judgement (Herman 73). Hutcheson was the first to teach in English rather than Latin at Glasgow University. As a moral philosopher, he has had a lasting impact on Scottish thinking as he advocated the universal right of freedom, attacking all slavery and was Europe’s first liberal thinker. An example of this liberal thinking is evident in India many years later in the formation and thinking of the Indian National Congress. Two Scots, Allan Octavian Hume (1829–1912) and Sir William Wedderburn (1838–1918) were founders of the Indian National Congress as a body that pressed for greater Indian representation and a stronger voice in India’s governance. Wedderburn and another Scot, the wealthy businessman, George Yule (1829–1892), were Presidents of the Indian National Congress.

Lord Kaimes (Harry Home), the Patron of David Hume and William Robertson, used a four stage analysis of human society and its progression: 1. Hunting, 2. Pastoral, 3. Agricultural, 4. Commerce/Industry. He proposed that changes in the means of production bring in historical change, so, for example, institutions like law have to alter as society alters. All of this led several leading Scotsmen to refrain from racial interpretations of history (not accepting slavery in Scotland).

David Hume, arguing against Hutcheson, radically said that reason is, and ought to be, the slave of the passions. The most basic human passion was self-gratification. Society’s problem was to channel passions in a constructive direction, meaning that liberty had to be counterbalanced by authority. In answer to Hume, Adam Smith referred to the inborn moral sense of human beings, speaking of a ‘fellow feeling’ which enabled one to place oneself in another’s position. In The Wealth of Nations (1776) Smith explored the nature of human progress, the notion of specialization and division of labour, whose importance grows with each stage in society. He also applied this notion to intellectual labour. However, he was critical of the British government’s defence of producers and pointed out the costs of capitalism. The sociologist, Adam Ferguson, recognized the danger of subservience to profit, while Smith believed that the benefits of capitalism were worth the price.

The polymath, Dugald Stewart, who replaced Adam Ferguson in the Chair of Moral Philosophy at Edinburgh University in 1785, was the intellectual bridge between the Scottish Enlightenment and the Victorian era as he ‘put the disparate works of the Scottish school together as a system, a system of classical liberalism’ (Powell 9). He promulgated a liberal optimism, and was the teacher of Lord Minto, ‘providing the ‘conceptual tools they could use as a framework for their analysis of Asian cultures’, creating some ‘distinctive Scottish paradigms of empire’ (Ibid.). In conclusion, the great insight of the Scottish Enlightenment was to insist that human beings need to free themselves from myths and see the world as it truly is.

Encyclopaedia Britannica, which was first published in Edinburgh from 1768 to 1771 in three volumes, was a product of the Scottish Enlightenment, the age of ‘new ideas’ (Powell 8) – as a compendium of knowledge which remains highly regarded, even today.

The Scottish Orientalist project, if one may call it so, goes back to a seminal Orientalist figure in the historian William Robertson (1721–1793), Principal of the University of Edinburgh, who wrote of a sophisticated civilization in India while resident in the Scottish metropole in Edinburgh. His 1791 volume, An Historical Disquisition Concerning the Knowledge which the Ancients had of India, traces the commercial links that facilitated a cultural exchange between the West and India. In this West meets East study, Orientalists who were writing in India like Quintin Craufurd (1743–1819) and his Sketches Chiefly Relating to the History, Religion, Learning and Manners, of the Hindoos (1792), become significant, who endorse a similar perspective, very much in the spirit of the scholar-administrators like Sir Thomas Munro (1761– 1827), Sir John Malcolm (1769–1833) and Hon Mountstuart Elphinstone (1779–1859) and the Muir brothers of Kilmarnock, John Muir (1810–1882) and Sir William Muir (1819–1905). The Muir brothers’ study of the original sources of Vedic and Arabic civilizations (Powell 10), are seminal works of Scottish Orientalists.

However, one notes a narrative shift in the change in perception of India in Western discourse, effected by another Scot, James Mill (1773–1836), through his significant six volume text, The History of British India (1817). Mill was deeply influenced by Dugald Stewart (1753–1828) who was his teacher at the University of Edinburgh. This History became a source of ‘knowledge’ for British personnel who came out to serve and rule India, as it was their recommended text. Mill’s History told them of the inherent ‘evil’ and ‘corrupt’ nature of the Hindu and his ‘depravity’, fuelled by his superstition and ‘primitive’ religion. The initial use of ‘Hindu’ in British discourse was a synonym for everything ‘Indian’, which, only in later times, was used for the religious majority of the sub-continent. The misreading of Indian civilization by Mill justified the sense of the colonisers’ ‘superiority’, which led to a disinterest amongst East India Company servants, and later employees, of the Raj in Indian culture, literature and the historical continuity of an old civilization that had been validated by earlier ‘Orientalists’ like Robertson. This project will study how the reading of history and interpretations of culture and literature have been instrumental in forming the minds of generations responsible for governing India, establishing business houses, managing plantations and trade in Indian produce in a global market.

Mill had never set foot in India and had no linguistic acquaintance with Indian languages, claiming his ‘expertise’ in India’s history from the distance of the metropole, in an act that marginalises India’s history through a written discourse based on second-hand knowledge, which takes on the aura of ‘authenticity’ associated with the written word. Mill’s treatise was further consolidated by another Scot, Thomas Babington Macaulay (1800–1859, who lived in India between 1834 and 1838) whose ‘Minute on Indian Education’ of 1835, passed the judgement that ‘a single shelf of a good European library was worth the whole native literature of India and Arabia’ (Sharp 109); sweeping statement made by a Member of the Governor-General’s Council, who, like Mill, did not possess any first-hand knowledge of Indian Languages or of Arabic. These texts were instrumental in constructing perceived notions as ‘facts’ about India, and the reality on the ground became secondary in an assessment of far-flung colonies, which could thus be written about, assessed and branded as ‘inferior’ without association with the people or the land that was being described–negating the human association so necessary for a fuller understanding of the people and their context. By these means, another ‘myth’ was constructed, the myth of Indian barbarism and decadence against Western rationality and superiority, negating and dismantling the view that was prevalent and practised during the Scottish Enlightenment. As Subrata Dasgupta has said, ‘the Scottish Enlightenment embodied not only rationalism but also a solid dose of Scottish practicality’ (Dasgupta, Awakening 146), which would be exemplified by the work on the ground carried out in the educational sphere by significant Scottish thinkers and pragmatists as will be discussed below.

Robertson did not visit India, but he preceded the Victorian, evangelist views, when there was still a certain respect for the wonder that was India and the sophistication of her civilization.

And as we have seen, Mill wrote about Indian history and made sweeping, definitive statements about India and Indians (and of Indian art, which will be discussed below) without ever visiting India. Macaulay dismissed all Arabic and Sanskrit literature without having any knowledge of any of the Indian languages and its continuous literary history that was over 3,000 years old. Later, Ruskin’s dismissal of the beauty, meaning and deep philosophy of Indian art and architecture would be based on secondary sources and information without any direct contact with examples of Indian art or debates with Indian art critiques (Mitter 244).

However, Mill’s representation of India continued to be challenged in subsequent publications, (e.g., in thoughtful analyses by John Crawfurd (1783–1868) in his History of the Indian Archipelago (1820) and, in A View of the Present State and Future Prospects of the Free Trade and Colonisation of India (1828).) There was also the French account by Anquetil-Duperron (1731–1805) who came to India in 1754, and whose work was rediscovered by Raymond Schwab in 1950. His La Renaissance Orientale was later translated into English in 1984 by Patterson-Black and Reinking entitled, The Oriental Renaissance: Europe’s Rediscovery of India and the East 1680–1880 (1984). This Orientalist perspective of India is considered a seminal text by Edward Said in his Orientalism (1978).

What we are looking at here, however, is pre-Saidian Orientalism (with a capital O) as opposed to Saidian/post-Saidian orientalism (with a lower case), in relation to India where Scots played a pivotal role in the civil, military, maritime and medical services at the beginning of the 19th century, in private businesses, in partnerships in agency houses in the Presidencies, particularly in Calcutta (Powell 6). The Saidian thesis that all orientalist endeavours were for the advancement and empowerment of the colonial state, as discussed by Michael Dodson in his Orientalism, Empire, and National Culture: India 1770–1880 (2007) establishing a discourse which was aimed at representing, speaking for, dominating and ruling the Orient, is not pertinent to this particular study. The pre-Saidian Orientalism was, in many cases, a self-fulfilling scholarly venture to gather knowledge and indulge in a cultural exchange with native scholars, which Bayly called ‘constructive orientalism’ in his Empire and Information: Intelligence Gathering and Social Communication in India 1780–1870 (1996), a term Dodson also uses with reference to the educational scene. This form of Orientalism has been called ‘neo-orientalism’.

The idea of a ‘Scottish School’ of Indian governance has been mooted by Martha McLaren in her British India and British Scotland, 1780–1830: Career Building, Empire Building and a Scottish School of Thought on Indian Governance (2001) and Michael Fry in his The Scottish Empire (2001). There is a general consensus about a Scottish ‘distinctiveness’ ‘in such spheres as governance, militarism and trade’ (Powell, 7) as has been noted by Philip Constable in ‘Scottish Missionaries’ (Constable 278-313). Michael Fry also speaks of a ‘discrete Scottish attitude to empire linked in general to the intellectual climate’ practised by Governor-Generals like Munro, Malcolm and Elphinstone (Powell 7). However, the idea of tracing a distinctive Scottish School or paradigm has been challenged by scholars like Jane Rendall in her article ‘Scottish Orientalism from Robertson to James Mill’, where she speaks of the intellectual influences of Scots in ‘a second “generation” of philologists and historians, who worked in the spirit of Robertson’s liberal humanism rather than under James Mill’s racist construct of India and her people (Rendall). The Muir brothers’ (Ibid.) generation of Scots did have some links with Rendall’s scholars like: Alexander Hamilton (1762–1864), James Mackintosh (1765–1832), John Crawfurd (1783–1868) and Mountstuart Elphinstone (all Haileybury pupils through their contacts in India). However, as Powell points out, a putative ‘third generation’ of Scottish scholar-administrators in the Muir brothers can be identified ‘at a considerable chronological remove from the original idea’ (Powell 9).

Warren Hastings (1732–1818), who came to Bengal in 1772 as Governor, was appointed Bengal’s first Governor-General from 1774 until 1785. Hastings was a key figure of this constructive orientalist group who believed that the British official serving in India should ‘think and act like an Asian’, having a good knowledge of the country’s literature, culture, its laws and history (Kopf 18). The Orientalists familiarized themselves with various facets of the Indian knowledge domain. Calcutta, as the capital of the Bengal Presidency, became a beehive of scholarly activity under Hasting’s Governorship. These Indophiles included the Sanskritists William Jones (1746–1794, founder of the Asiatic Society in 1784), Henry Colebrook (1765–1836 who wrote Sanskrit Grammar and translated Indian law texts), Nathaniel Halhed (1751–1830) who wrote the first Bengali grammar), Charles Wilkins (1749–1836 who translated the Bhagvat Gita into English), James Princep (1799–1840 who deciphered the Bramhi script of ancient India) and Robert Chambers (1737–1803, third President of the Asiatic Society, who was interested in law and literature) (Dasgupta, The Bengal Renaissance 24, 31).

These eighteenth century men actually preached and practised such a professional cosmopolitanism, a scholarly ideal perhaps best exemplified by the Asiatic Society (Curley 370).

According to David Kopf, these scholar administrators were ‘classicists’, cosmopolitan and rationalists rather than ‘progressives’, nationalist and romantics; they were very much products of the European Enlightenment (British Orientalism 22).

They were all Englishmen, apart from Sir William Jones, who was Welsh. Their Scottish counterparts, who were legatees of the Scottish Enlightenment and are identified by many scholars as Scottish Orientalists, may be described in Kopf’s terms as progressives, nationalist and romantics. They fell into a different category of men who would influence the ‘Awakening’ of the Bengali mind (Ibid. 19; Dasgupta, Awakening 2) in no uncertain terms as they moved away from a focus on classical Sanskrit scholarship to vernacular Bengali and to education in English. It is in the area of educational and cultural reform and in their association with Indian reformers, that Scottish Orientalists influenced and facilitated the Bengal Renaissance, which would later affect all of India. Though they did not study William Robertson’s history of India at University, his book was available and read and his views on India were well known: ‘to him (Robertson), the cave temple–one of the earliest forms of architecture–indicated a developed state of society, as equally the sculptures in them reflected considerable achievement for the period (Mitter 177).

These Scottish Orientalists were not influenced by James Mill’s The History of India. According to Mill, India’s crudeness and barbarism could be detected in her art. In his estimation, not only was Indian art ‘primitive, unattractive, rude in taste and genius’, but ‘unnatural, offensive and not infrequently disgusting… The Hindus copy with great exactness, even from nature. By consequence they draw portraits, both of individuals and groups, with a minute likeness; but peculiarly devoid of grace and expression…They are entirely without a knowledge of perspective, and by consequence of all those finer and nobler parts of the art of painting, which have perspective for their requisite basis’ (Ibid. 176, 177). This strong indictment of Indian artistic expression, the culmination of her civilization according to Mill, is not evident in the consciousness of Scottish Orientalists.

George Davie in his work, The Democratic Intellect: Scotland and Her Universities in the Nineteenth Century (1961), speaks of the generalist education in secondary schools in Scotland, which offered a Universalist body of knowledge–very school worth mentioning at this higher education today. The Scottish secondary schooling system had philosophy at its core, rather than the classics, which, Davie notes, marked the English system. In Scotland, a general education that covered poetry, philosophy, science and mathematics, did not see these subjects as competitors, but together they accounted for an intellect that was philosophical, scientific and humanist, hence ‘democratic’. Murdo Macdonald in his ‘Introduction’ to the 2013 edition of Davie’s book, links the intellectual traditions of the Scottish Enlightenment to those of today. Patrick Geddes (1854–1932), a generalist who will be discussed later, welcomed this scientific approach to teaching, affirming that any aspect of knowledge, culture or society benefits from illumination of all other aspects, (Macdonald 77). Davie’s idea of the Democratic Intellect has been challenged as too simplistic by some scholars, while hailed and accepted by others like Macdonald and the Indian historian, Barun Dey.

We have already discussed one Scot who was responsible for the introduction of English education and Western science first in Bengal, which soon spread across India, namely Thomas Babington Macaulay. This clever but audacious proposal to create a band of brown sahibs (there is no mention of brown memsahibs here) in India, ‘Indian in blood and colour, but English in taste, in opinions, in morals, and in intellect’ (Sharp 116) so that the British could create a brand of loyalists amongst the natives and continue to rule by proxy, reaped tremendous benefits for British rule for over a century. However, this step also generated ideas of modernity, of democracy – humanist ideas emanating from the British and Scottish Enlightenment, ideas of freedom, the dignity of man and the right to question and challenge as thinking, debating individuals and societies – questioning and answering the British in their own words, in a language they understood, English.

This brings us to the discussion of two Scots, David Hare and Alexander Duff, who were central figures in Calcutta, influential in the education sector and who contributed to the developments that would become the cornerstone of higher education in modern India. We have the story from Peary Chand Mitra (1814–1883) that on one occasion when Raja Rammohan Roy (founder of the Bramha Samaj in 1828 and the leading spirit of the Bengal Renaissance) was with his friends in his Calcutta home, he mooted the idea of forming an ‘Atmiya Sabha’ to discuss and address the ‘moral condition’ in Hindu society.

One person who was present at this gathering was David Hare (1814–1883), a Scottish watchmaker and philosopher from Edinburgh. Hare was an atheist, outside the Presbyterian/Anglican fold of missionary activity in India. It was Hare who came up with the proposal of educating ‘native’ youths in Western/English literature and science to enlighten them effectively and free their minds of ‘pernicious cants’ (Mitra, XII). Dasgupta calls the Scottish Orientalists ‘tinkers as well as thinkers’ (Awakening 146). Thus Hindu College, the forerunner of Presidency College (now Presidency University), was conceived by David Hare and supported warmly by Raja Rammohan Roy. It was established on 20 January 1817 and it celebrated 200 years of its anniversary in January 2017. Its fundamental objective was ‘the tuition of the sons of respectable Hindoos in the English and Indian language (sic) and in the literature and science of Europe and Asia’ (Ibid. 147). However, the religio-caste-class imperative meant that Raja Rammohan Roy, who was shunned by a section of prominent Orthodox Hindus as a Bramho, had to distance himself from the actual foundation of the College. David Hare’s proposal of educating ‘native’ youths in Western/English literature and science was practised at Hindu College, which in 1828 had 400 students receiving English education. By 1835 there were 24 schools offering English education. Hare School remains a testimony to his role in Education (Ibid. 150). He was also the founder of the School Book Society and an initial force behind the idea of promoting the education of women in Bengal.

Of Raja Rammohan Roy, one can say that he did not just belong to a great epoch of change that would help India to become a modern nation, but was the creator of an epoch, responsible for its epochal revolution through his untiring advocacy for religious, social and educational reforms. He was the initiator of the Bengal/Indian Renaissance and we owe the study of English, of education in English in India to Raja Rammohan Roy’s initiative. He has been considered ‘The Father of Modern India’ (Bruce Carlisle Robertson, 1999). The Director of the East India Company had set aside one lakh rupees for education, which the Orientalists wanted for Maulvis, Pundits, Sanskrit and Arabic scholars to use. It was Rammohan Roy who changed the course of our socio-cultural history with his famous letter to Lord Amherst, dated 11 December 1823, in which he wrote:

We now find that the government is establishing a Sanskrit school under Hindu pundits to impart knowledge as is already current in India. This seminary can only be expected to load the minds of the physical distinctions of little or no practical use to the society... The Sanskrit system of education would be best calculated to keep this country in darkness... But as the improvement of the British native population is the object of the government it will consequently promote a more liberal and enlightened system of instruction, embracing mathematics, natural philosophy, chemistry and anatomy with other useful sciences which may be accomplished with the sum proposed by employing a few gentlemen of talent and learning educated in Europe, and providing a college furnished with the necessary books, instruments and other apparatus (Sharp 99, 100, 101).

Rammohan Roy did not receive an answer to his letter. Sanskrit College, which was established in 1823, remains an institution which is a great part of India’s heritage and is of contemporary relevance. However, the ripples Rammohan Roy caused had phenomenal effects. Twelve years later, on 7 March 1835, Lord William Bentinck passed a Resolution on Education which was based on Macaulay’s ‘Minute’ written earlier on 2 February 1835. Rammohan Roy’s letter was part of what was called the ‘Anglicist-Orientalist controversy’ where ‘Orientalist’ refers to the proponents of Sanskritist classical learning and education in India.

Raja Rammohan Roy’s close associate and friend was Prince Dwarakanath Tagore (1794–1846, Rabindranath Tagore’s grandfather), the appellation of Prince signifying his philanthropy and generosity. Dwarakanath studied at Sherbourne’s School in Calcutta. In fact, he was so grateful to Sherbourne, that he gave them a life stipend after his teacher retired. Dwarakanath was, also, taught by several Scottish teachers – William Adams, J.G. Gordon, James Calder–and later on, he gained proficiency in law under the guidance of the Scottish Barrister, Robert Culler Fergusson. Dwarakanath financed several educational institutions in his lifetime. While Raja Rammohan Roy is known as the Father of the modern Indian nation, one can say that he and Dwarakanath, who spearheaded the Bengal Renaissance, were architects of modern India with the impetus they lent to religious, social and educational reform and in Dwarakanath’s case, to economic entrepreneurship.

One school worth mentioning at this juncture was the Dhurromtollah Academy run by David Drummond (1785–1843) – a Scot and a theological dissenter. He objected strongly to Phrenology and his students imbibed his way of freethinking and analysis. Both Hare and Drummond carried the legacy of the Scottish Enlightenment in their sceptical rationalist approach (Drummond was the author of Objections to Phrenology, 1829), which is evident in their work in education in India. Henry Derozio, the brilliant firebrand poet and Indian nationalist who taught at Hindu College between 1828 and 1831 (dismissed in 1831) had studied at Drummond’s school. The band of Derozio’s followers at Hindu College, called ‘Young Bengal’, vociferously dismissed traditional Hindu ways and Bengali culture and literature as they espoused western ways. What is significant for us today is the Academic Association which was set up by the Derozians for their discussions and debates, mainly on poetry and philosophy, all of which were conducted in English. Derozio signified the spirit of a new age in his brief academic life and career; where the freedom of thought and expression, the nationalist spirit of India and the gateway to the West and the world, through the medium of English, steered a section of society in Calcutta on a tide that would spread and embrace the whole country.

The role that education played in the evolution of modern India was further exemplified in an estimation of the contribution the first Scottish Free Church Mission missionary, Rev Alexander Duff (1806–1878). Duff spent three periods in India: 1830–1834, 1840–1851 and 1855–1863. He was a friend and associate of Raja Rammohan Roy’s before the latter sailed for England. Rammohan Roy was a close associate of both David Hare and Alexander Duff. At the General Assembly institution (later Scottish Church College), where Duff was superintendent, science and English were taught with a view to introducing a progressive value system to Indian students, very much in the same vein as Hare had suggested. In spite of Duff’s missionary zeal and proselytizing mission, he engaged the students in secular debates at Hindu College where he taught, encouraging freedom of thought and expression. Duff worked with William Carey at the Serampore Press and published books on Bengali Grammar and the Bible in Bengali. We see a marked shift in Duff from the earlier school of British Orientalists, as Duff valued vernacular language and education alongside English education, while the classicists of Hasting’s time went back to what they considered the classical ‘golden age of India’ exemplified in its Sanskrit literature. The Scottish intervention in modern education in India helped to shape much of the intellectual horizon of the Bengal Renaissance.

The West had travelled to India, and a reverse track was in turn initiated during the early years of the Bengal Renaissance by Raja Rammohan Roy and Dwarakanath Tagore who both travelled to England where they died and were cremated. At the heart of a Bengal Renaissance reform movement for social and educational reform, stands the Tagore family, emanating from Prince Dwarakanath Tagore, continuing in his son, Maharshi Debendranath Tagore (1817–1905), who was the leader of the Bramho Samaj, a monotheistic movement, which gave fresh impetus (1842–43 onwards) to validating the Upanishadic tenets of Hindu philosophy and had a deep interest in Unitarianism. The dissenting voices reflected amongst Bramho activists, and the role of the Tattwabodhini Sabha and the journal, the Tattwabodhini Patrika, embody the centrality of ideas in a society that was confronting the challenges of transformation on the socio-religious front. One can say that Debendranath’s son, the Nobel Laureate, Rabindranath Tagore (1861–1941), is the grand figure who, with his grandfather, Dwarakanath, bookended the Bengal Renaissance. Rabindranath was a pivotal figure who contributed substantially to bringing India to its modern status, willing to see the modern validation of ancient and medieval Indian thought, while welcoming the meeting of minds from the West and East in a mutually beneficial syncreticism.

As has been said before, this study is not about the Bengal Renaissance, but about the impact of Scottish Orientalists on this transitional epoch. We have highlighted the influential role some Scots have played in English education in India. We will end with a reference to the opinions of some Scottish critics on Indian art and architecture, which are suggestive of an appreciation of an Indian heritage and its aesthetic expression, which is very different from the Western ‘standard’ of what is beautiful, moral and acceptable as postulated by John Ruskin. Ruskin wrote in the league of scholars who took their cue from James Mill’s History of India. While Ruskin’s dismissal of the beauty, meaning and deep philosophy of Indian art and architecture was based on secondary sources and information without any direct contact with examples of Indian art or debates with Indian art critiques, some significant Scottish Orientalists’ descriptions and critiques of Indian art and edifices were written on first-hand experience. Thus, Alexander Cunningham (1814–1893) says of the Khajuraho temple, ‘the general effect of this great luxury of embellishment is extremely pleasing although the eye is often distracted by the multiplicity of detail’ (Keay 128). James Fergusson (1808–1886, son of an Ayrshire doctor), was ‘the historian of India’s architecture’ (Ibid. 118) and author of History of Indian and Eastern Architecture (1876); he gathered photographs of 3000 Indian buildings, praising them ‘for an exuberance of fancy, a lavishness of labour and an elaboration of detail’ (Ibid. 147). He notes ‘the glory of Hindu architecture’ (Ibid. 156) in Bhubaneswar temples and speaks of the temple at Halebid as ‘a masterpiece of design in its class’. He comments that ‘the artistic combination of horizontal with vertical lines, and the play of outline and of light and shade, far surpass anything in Gothic art’ (Ibid.). He goes on to say, ‘all that is wild in human faith and warm in human feeling is found portrayed on these walls’ (Ibid.). However, there is an echo of Ruskin when he concludes that ‘but of pure intellect there is little’ (Ibid.). However, he is appreciative of the Qutab Minar (Ibid. 160) and of the Taj Mahal; he says, ‘what made the Taj unique was its sculptural quality’ (Ibid. 165). These art historians go back to medieval India in their appreciation of her aesthetic splendour and achievements. What is significant here is that they were writing and commenting on India’s ‘human faith’ and ‘warm human feeling’ during the period of the Bengal/Indian Renaissance, affecting public opinion on India in the West.

Scotland remained a destination for many Indian scientists, engineers and teachers. Scottish researchers, like Sir Ronald Ross (1857–1932) who was born in India and won the Nobel Prize in 1902, and the botanist, William Roxburgh (1751–1815), the first Superintendent of the Botanical Gardens in Calcutta (1793–1813), who conducted their research in India, made significant contributions to the Indian scientific field. The philanthropist, Sir Daniel Hamilton from Arran, settled in India and was involved in establishing cooperatives, introducing microcredit and working for the rural regeneration of communities in the Sundarbans.

The East-West dialogue that was generated as a result of this encounter in India, would be continued by several Renaissance figures who travelled from India to the West in the earlier 20th century, like Acharya Prafulla Chandra Ray who studied at Edinburgh and Sir Jagadish Chandra Bose and Rabindranath Tagore were friends and close associates of the Scottish polymath, Sir Patrick Geddes. To Geddes, we owe the preservation and conservation plans of around 50 towns and cities in India, markedly Varanasi. In India, the clock that had been deftly wound and set ticking by Scottish Orientalists like David Hare, would continue to witness fresh developments and the expansion of education in India that is in tune with global trends today.