0,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Arcadia Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

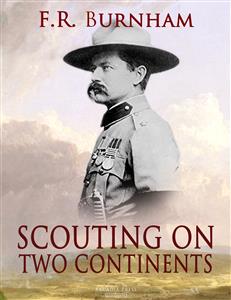

Frederick Russell Burnham: Explorer, discoverer, cowboy, and Scout.

Native American, he served as chief of scouts in the Boer War, an intimate friend of Lord Baden-Powell.

As an honorary Scout of the Boy Scouts of America (BSA), he has served as an inspiration to the youth of the Nation and is the embodiment of the qualities of the ideal Scout.The BSA made Burnham an Honorary Scout in 1927, and for his noteworthy and extraordinary service to the Scouting movement, Burnham was bestowed the highest commendation given by the BSA, the Silver Buffalo Award, in 1936. Throughout his life he remained active in Scouting at both the regional and the national level in the United States and he corresponded regularly with Baden-Powell on Scouting topics.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

F. R. Burnham

SCOUTING ON TWO CONTINENTS

Copyright © F. R. Burnham

Scouting On Two Continents

(1927)

Arcadia Press 2019

www.arcadiapress.eu

Storewww.arcadiaebookstore.eu

TABLE OF CONTENTS

SCOUTING ON TWO CONTINENTS

To my Wife

Blanche Blick Burnham

“Englandwasnevermadebyherstatesmen; Englandwasmadebyheradventurers.”

GENERAL GORDON.

THE ADVENTURERS

They sit at home and they dream and dally,

Raking the embers of long-dead years —

But ye go down to the haunted valley,

Light-hearted pioneers.

They have forgotten they ever were young,

They hear your songs as an unknown tongue,

But the flame of God through your spirit stirs,

Adventurers — O adventurers!

They tithe their herbs and they count their tally,

Choosing their words that a phrase may live —

But ye cast down in the hungry valley

All that a man can give.

They prophesy smoothly, with weary smile

Fulfilling their feeble appointed while,

But Death himself to your pride.defers,

Adventurers — O adventurers!

MAY BYRON

Extractfromaletterfrom LT. GEN. SIR ROBERT BADEN-POWELL, K. C. V. O., K. C. V., writtenfromAfricatohismother, in1896:

“12th June, 1896… Burnham is a most delightful companion… amusing, interesting, and most instructive. Having seen service against the Red Indians he brings quite a new experience to bear on the Scouting work here. And while he talks away there’s not a thing escapes his quick roving eye, whether it is on the horizon or at his feet.”

FOREWORD

SOME years ago, Sir Rider Haggard said to me, in regard to Major Burnham: “Burnham in real life is more interesting than any of my heroes of romance.” This appreciation by the author of “King Solomon’s Mines,” “Allan Quatermain,” and “She” was no idle compliment, but was earnestly expressed, and I know that the readers of this book will agree with the famous novelist that truth can be stranger than fiction.

Haggard also told me that he tried his best to induce his friend Burnham to give him material for writing a series of magazine articles, and that Lord Northcliffe had offered Major Burnham £2,000 to dictate broadly his exploits, but that Burnham, from excessive modesty, had firmly turned this offer down. Such characteristic refusals account mainly for the fact that Major Burnham remains relatively unknown to the American public while his fame is spread throughout England and the English Colonies, where no modesty on his part could possibly suppress the record of his exploits in South Africa, the scene of his many extraordinary adventures.

Of the many Americans who have contributed service to the winning of South Africa from barbarism, no one is held in. higher esteem than Frederick R. Burnham. His extraordinary accomplishments, unblemished character, and winning personality fully earned the high praise bestowed upon him by the people of South Africa and the patriotic pride of his fellow Americans in that country.

I recall a conversation with Cecil Rhodes when discussing the winning of Rhodesia, that great territory about the size of California, which lies south of the Zambeszi River and contiguous to the Transvaal on the north. Rhodes had been reading a letter which he passed over to me with the explanation that it was in reply to one that he had written to Burnham after the first Matabele War in 1894. Rhodes said that he had asked Burnham to suggest some way in which the British South Africa Company, the owner of the country afterward called Rhodesia, could recognize the invaluable service he had rendered as a Scout in that war. Burnham’s reply, and I well remember it, was to this effect: “While I appreciate the honour you pay me, in your generous estimate of the service you consider I have rendered, and your offer of recompense, I must frankly tell you that the part I played was not with the object of promoting the interest of your company but was in defence of the lives of the people who were at that time besieged by hordes of savages under Lobengula. For that reason I cannot consistently accept any reward, but I sincerely hope that I shall be able to retain the appreciation you have expressed by what I may be able to accomplish in the future.” Rhodes exclaimed, “What an extraordinary letter! It is a rare experience to have an offer of that kind turned down.” I said, “Yes, but you respect him the more for having done so.” Later, Rhodes persuaded Burnham to accept a concession of mineral land as a token of his appreciation.

One of the most enthusiastic admirers and devoted friends of Major Burnham was the late Lord Grey, at one time Administrator of Rhodesia and subsequently Governor General of Canada. Lord Roberts, Lord Milner, General Sir Baden-Powell, identified with South African history, were among his many admirers and friends. Lord Roberts had a special admiration and fondness for Major Burnham, and whenever I happened to visit London, would call to see me particularly to make inquiry regarding his health and welfare.

While I have said his fame has not reached the American public generally, Burnham was, nevertheless, well known to Theodore Roosevelt, Hopkinson Smith, Richard Harding Davis, Thomas Nelson Page, and other prominent Americans who greatly enjoyed his company. Hopkinson Smith, not a mean judge, once told me that he regarded Burnham as the best story-teller he had ever met. I recall spending several hours with Roosevelt and Burnham after a luncheon at the White House, to which we had been invited by President Roosevelt, and no higher tribute could be paid to the absorbing interest of Burnham’s narrative of South African adventures than the mute admiration of Roosevelt as he listened without interrupting.

In addition to the fund of thrilling experiences that some of his intimates could by skillful manoeuvring induce Burnham to recite, his comprehensive, clear, and original views, his picturesque exposition of great national and international problems were in themselves a source of edification and enjoyment to those privileged to discuss such matters with him.

No life of Major Burnham would be complete without a reference to his wife. She has been an ideal helpmate in his career, often sharing great hardships and dangers in his field of strenuous activity. An inspiring and sustaining influence in his life, she is held in the highest esteem by his host of admirers.

The writing of this book has long been delayed, and it is only after years of persistent endeavour on the part of a few friends, of whom I am proud to be one, that Burnham has been prevailed upon to write this autobiography.

JOHN HAYS HAMMOND.

WASHINGTON, D. C. June 5, 1925.

INTRODUCTION

IT WAS a dozen years ago, during a motor trip with Mr. and Mrs. John E. Marble of Pasadena through the park-like country around Paso Robles, that we were joined by a certain Major Burnham, gold miner, hunter, and explorer, as well as Chief of Scouts under Lord Roberts in the Boer War, whom Mr. Marble knew and the rest of us had long wished to meet.

We saw a rather short man dressed in gray, the colour of his thick wavy hair; with the fair skin and regular features of the typical Anglo-Saxon, resolute cleft chin, excellent teeth, firm but expressive lips, large, well-shaped head well poised on an erect, broad-chested frame, strong, compact-looking hands — emphatically a man’s man, able, active, alert.

His way of striding up and down while talking, his step as elastic and noiseless as that of prowling lion or competent burglar, seemed peculiarly characteristic of his abounding vigour of mind and body; yet this quiet, unassuming gentleman would never pass unnoticed in a crowd did one but glimpse his eyes, blue eyes of startling keenness and brilliancy, eyes that see everything without seeming to see, eyes that at times are as cold and fierce as the steel of a drawn sword, yet, when laughing with his wife, as tender and merry as a boy’s.

To the mere physical outline must be added the impression he makes on all of force and self-control, leading one to visualize his true nature; not merely that “infinite capacity for taking pains” which marks the genius or the scout, but that delicate soul balance of experience and judgment which is, perhaps, man’s highest achievement, and which shines forth to be recognized even by those who have no knowledge of the actual record of accomplishment. All this I saw then and continue to see in the Major’s personality, and the divine fires of my hero worship have never dimmed through the everyday of pleasant friendship that has followed.

As we drove along the lovely wooded country of San Luis Obispo County, the Major sharing the rear seat with Mrs. Marble and me, we were given sudden and vivid proof of the famous readiness and resource of our new companion. My husband was at the wheel, and we were starting down a steep and narrow hill road when the brakes began to slip. At that instant, around a curve, over a light bridge at the foot of the hill, we saw coming toward us a very old man driving a pair of skittish horses. High tragedy seemed inevitable — when out of the tonneau without touching the sides sprang the Major and had a boulder lodged under the wheel and the perilous car stopped in the very nick o’ time! Never have I witnessed such quick action.

That same day, after a picnic luncheon together, beneath a great sycamore in a broad dry arroyo, my husband had the temerity to ask our new acquaintance to tell us how he killed the M’Limo in South Africa. I caught my breath until, with a cordial smile, the Major had consented, and held us all spellbound by the charm and interest of his recital. Just as he was describing the awful suffering of the children from improper and insufficient food during the siege of Bulawayo and the tragic loss of his own little girl, he said quickly: “We’ll kill that snake when I finish the story.” We followed his glance, and there, only a few yards away, a big rattler was coiled. So absorbed were we all in the Major’s narrative that we were as if hypnotized, and no one stirred until the end, when the Major seized a stick and, with the litheness of a boy of twenty, made for the snake.

This, then, was the beginning of a friendship that led on to the moment when I said solemnly: “It is very, very wrong, Major, not to preserve the account of a life so full of value and interest as yours. If only for the sake of your lovely young granddaughter, Martha, the whole story should be told.” The Major replied, “Will you help?”

To say that I was deeply gratified ill describes my satisfaction. I knew well how the reticence of a brave man too often proves an insurmountable barrier against either admiring personal persuasion or the clamour of public curiosity; and a further obstacle in this case had always been the perpetual motion of the object pursued, since the Major is such an unusually active person, leading a tremendously busy life, flying here and there and back and forth on important missions; and when called in consultation on momentous matters thousands of miles from Los Angeles, starting off at a moment’s notice, so that the moss of memoirs could hardly be looked for on this rolling stone. But at last the moment had come! To be sure, my competence for my proud task was much like that of the Irishman when asked if he could play the fiddle at a dance: “Shure an’ I wull thot! Fer isn’t it mesilf is afther watchin’ many’s th’ toime?”

Thus a joyous adventure began for me, while the Major found himself driven along a hard road with a relentless whip ever on his flanks, having learned straightway that it was himself and not I who was writing his story.

He would sit at his desk with the air of a determined martyr while his merciless prodder kept urging, “Tell about this!” and “Tell about that!” and when he handed the pages over with a patient sigh, my reproachful voice would keep on prodding: “You have neglected to put in the best part!”

“Why do you leave out that?” “Where is the liaison between this adventure and the next?” “Fie! Fie! Major, you are too modest! Back must go every one of those I’s you are eternally dodging” — for, alas! I discovered that even a superlatively courageous man has his fallibility. The Major, the brave Major, is in abject terror of the small pronoun I. Yes, I have seen my hero fairly squirm, and his teeth almost chatter at sight of that diminutive black object, but I have remained adamant on that point, for well I know that if the Major were to be given his way with that little pronoun, this book would have been written so that the dear Dumb Reader would never get so much as the ghost of an inkling as to whom it is all about.

Of the Major’s comrade-at-arms through all his wars and wanderings, he wrote to me:

In boyhood it was my greatest good fortune to meet a girl who truly believed in me and that I would carry out the wild schemes and plans which I confided to her. Fantastic as those dreams were, nearly every one has come true. The vision of all she would be called upon to endure amid appalling circumstances was mercifully hidden from her young eyes, nor could she foresee how tragedy and sorrow would some day test her soul as by fire; yet, throughout all the hard experiences of our years together, no resentment of destiny ever showed in her manner or crossed her lips.

A gentle heart, a pleasant voice, a loyal nature, with a wide understanding of life as it is — she has indeed met every situation with supreme courage and continues to be a clear fountain of inspiration to me and to all who know her.

Heartily can I echo my young daughter’s dictum after a visit we had enjoyed from the Burnhams — “Yes, Mother, the Major is very wonderful, but Mrs. Burnham is stillmorewonderful.”

MARY NIXON EVERETT.

ARDEN ROAD,

PASADENA, CALIFORNIA.

June1, 1925.

CHAPTER I

THE MAKING OF A SCOUT

MY ADVENTUROUS ancestors, emigrating from England during the turbulent religious wars, carried a fierce love of freedom and great physical energy into the New World.

My father, Edwin Otway Burnham, was born in Kentucky, his Connecticut grandfather with his Virginia bride having already pioneered “across the Ridge.” The family of my mother, Rebecca Russell, did not reach America from England until after the Black Hawk War. They pioneered to the then extreme frontier beyond the Mississippi, where, at a hamlet called Le Clair, my mother studied the three R’s in the same little log schoolhouse with Colonel Cody — “Buffalo Bill.”

In 1862, the black tornado of the War of the Rebellion was sweeping the land, and the young and strong were being sucked into its path from all parts of the country. Out on the frontiers of Minnesota, the few settlers who remained kept their holdings, in constant peril from hostile Indians. Emboldened by the depleted condition of the settlements and stung by repeated deceptions and injuries suffered at the hands of the whites, ten thousand Sioux under Chief Red Cloud swooped down on the Minnesota pioneers at New Ulm, setting fire to the town and killing and scalping the inhabitants.

At this time, my parents had just moved from Tivoli, on the Indian Reservation where I was born, to our new homestead some twenty miles from Mankato. As our home lay in the path of the raiders, my father left at once for Mankato for powder and bullets to protect his family, in case of need. He found three thousand terrified settlers, scantily armed, huddled in the town in instant expectation of attack. He was, therefore, unable to procure any ammunition to carry away for his own use.

Left alone in the log cabin except for myself, an infant of two years, my mother was keeping a sharp lookout for any sign of hostiles. Not many nights earlier, she had seen the sky turn red and learned soon afterward of the burning of New Ulm, where three hundred men, women, and children had been tortured and slain. Early one evening, as she stood in the doorway brushing her hair, she suddenly spied with horror a band of Indians moving out of the timber along the creek, not far away. Realizing that she could never escape if hampered with her baby, she decided instantly to hide me in a stack of newly shocked corn. The corn was too green to burn, and if I should make no outcry, I might escape discovery. So she tucked me into the hollow depths of a shock and earnestly adjured me to keep perfectly still, not to move or make the slightest sound until she should return. As she was young and strong and exceptionally fleet of foot, she managed to reach some hazel bush on the edge of the clearing just as the Indians surrounded the cabin. She saw the hostiles hunting all about, and then some of them started on her trail, but she was hidden by the cottonwoods as she moved swiftly along the stream. Through the increasing darkness and her desperate speed, she succeeded in outdistancing her pursuers and reaching a barricaded cabin six miles away, but long before she reached safety she saw the flames of her own home rising to the sky.

At daybreak the next morning, she returned with armed neighbours to look for her baby. She found me, as she often loved to tell, blinking quietly up at her from the safe depths of the green shock where I had faithfully carried out my first orders of silent obedience.

The burning of New Ulm and other horrors perpetrated by the Indians were promptly avenged by the pioneers. Under Governor Sibley of Minnesota, punitive measures were taken, the details of which are celebrated in Minnesota history. On December 26, 1863, thirty-eight Sioux chieftains were tried and condemned to death by hanging at Mankato. I remember hearing my parents relate vividly how the braves met their fate singing the Sioux war song; undaunted, exultant, and defiant to the end. A pioneer of New Ulm, whose sick wife and children had been burned alive by the Indians, was given the precious privilege of cutting the ropes that let the thirty-eight warriors drop into Eternity.

Those were rough days and fierce resentments. To-day, recalling all the crimes of the Indians, which were black enough, one cannot but cast up in their behalf the long column of wrongs and grievances they suffered at the hands of the whites. Then hatred dies, and I can entertain the honest hope that they have all reached the Happy Hunting Ground of their dreams.

But the dark side of the lives of the pioneers, measured in terms of tragedy and hardship, violent feuds and religious intolerance, and Indian massacres, does not tell the whole story. The daily tasks, the hours of relaxation, the eternal love theme woven by joyous youth into the scheme of things • — these made up the sunshine of those days.

The years following the return of the soldiers from the Civil War brought to Minnesota strong and able hands to assist the settlers. New houses, barns, roads, fences, made their appearance. My father, having constructed a house of sawn lumber, decided to tear down our log cabin and build it over into a barn. A recent flurry of snow covered a shallow, icy pool lying between the cabin and the barn site. My mother suggested hitching up the team to move the logs, but for answer, Father, who was a very strong man, swung a log on his shoulder and started with it toward the site. Mother and I turned away toward the house. Glancing back, I saw Father slip on the snow-covered ice and, as he went down, the great log fell upon him. It crushed his lung so that he spat blood, yet a few days later he insisted that he was quite well enough to go into the timber with the team. He drove home in a howling blizzard, and a cold settled on the injured lung and persisted so long that he was finally persuaded to go to California for a cure.

Our little family of four started west in the winter of ’70, crossing the state line in January, 1871. It was a two weeks’ trip from the Mississippi River by the new railroad. Buffalo were still to be seen along the way. Extra provisions were carried by each train in case it should be snowbound indefinitely. Considering all the difficulties that had to be overcome and the meagre equipment for the task, that first railroad to California was and still is a monument to the builders. Constructive courage of the highest order was called for in every mile of its length.

How shall I write of California, the new world into which I dropped as from a cloud at an age when every scene and every event left its vivid imprint on my memory? The rugged qualities acquired in Minnesota found themselves expanding in a glorious atmosphere of ease. Yet soft and golden as life in California appeared to be, I soon found that it would require just as much energy to succeed there as in the sterner land of my birth. Moreover, every phase of my new experience seemed impelling me to take desperate chances. Years later, I found much of the same recklessness prevalent in South African life. I sometimes wonder if this pioneer spirit of high adventure — what scientists might call our peculiar racial urge — has been swept away for ever by the vast wave of alien immigration in recent years. I hope not!

As my father was searching for health, we journeyed from place to place and at every ranch found hospitable doors standing wide open. Each hacienda was a principality in itself. To my boyish fancy, the whole world was bounded by the mountains at the back of us and the broad blue sea in front. The thousands of horses and vast herds of cattle move again through my memory as I saw them in those days. All the incidents of the new life keenly interested me — the fiestas and fandangos, the hard riding, and the great rodeos where the annual crop of beef hides was gathered and shipped in strange old vessels or small coast steamers to some distant region inhabited by Yankees, peculiar beings, of whom Californians thought vaguely or not at all. We lived simply. We had little money and cared less about it. Nature was bountiful, the acres were broad, the boundaries very dim. There seemed to be plenty for all. For the greater part of the year, California was one long summer afternoon.

I was first under fire when about ten years old. My father undertook to act as arbitrator between some Mexicans and Americans who were having a fierce contest over the boundaries of one of the old Spanish land grants in Contra Costa County. We drove to a Mexican rancho in an old buckboard, and my father talked to the Mexicans for some time, in an endeavour to bring about a peaceful settlement of the difficulty. One of the Americans concerned — an old man who was very keen to find out the result of the conference — had, without intending any harm, trailed along behind us and taken up a strategic position on a hillside, where he sat waiting for my father to come back with his report. On our return from the rancho, several of the Mexicans, mounted and with loaded rifles, followed along behind us. We had travelled perhaps a mile or two when we came to the old man sitting on the hillside. The suspicious Mexicans at once concluded that my father was in collusion with the Americans instead of acting as a disinterested go-between, and they immediately opened fire, both on the old man and on our horse and buggy.

The sharp crack of the guns and the little spits of dust flying up several feet in the air where the bullets struck all around us made a very vivid impression on my boyish mind, and when I saw the old fellow throw up his arms and fall down the side of the hill, I was quite sure I had seen my first man slain in battle. At the splatter of bullets and the ricochet of one that hit the buggy tire, our horse bolted down the road at a tremendous pace. Fortunately, some distance from the scene of the shooting, we were stopped by a gate in the road. We then went back to pick up the corpse of the old man. We found him alive and unscathed. As he was unarmed he had simply adopted the ruse of throwing up his hands and falling over. The Mexicans, thinking they had killed him and not wishing to follow up the fighting any further, had retreated to their ranches. Although the little battle proved a bloodless one, it stirred my pulses in a most lively manner and indeed influenced my entire career. Assuredly no knight ever received his accolade with a more definite thrill.

The death of my father in 1873 compelled me to join somewhat in the new order of things and take up the strenuous life. My mother’s health had broken, and as my brother Howard was but three years old and I not yet thirteen, there was no visible support for the family. But when some kind uncles offered us all a home in the East if we would return, I determined to stay in California and make my own way. A friend in Los Angeles, a Mrs. Porter, lent my mother the money to pay her fare east. I set myself the task of repaying this, to me, vast sum of money — one hundred and twenty-five dollars. At the age of thirteen, I became a mounted messenger for the Western Union Telegraph Company. Their wire ended in the old pueblo of Los Angeles, and their messages were carried by means of swift horses to all the outlying towns and haciendas within a radius of thirty miles. I supplied my own mounts for this work, and they paid me twenty dollars a month for the regular run; but when I had to ride outside and at the dead of night, as I frequently did, to Lucky Baldwin’s Ranch or to Santa Monica, Anaheim, or San Pedro, I got extra pay. It was not long before I was able to wipe off the slate all but the lasting debt of gratitude which I still owe to the kind Mrs. Porter. While doing this work, I first discovered that I had more endurance than other boys. I found that I was able to change horses and stay in the saddle, not only all day, but far into the night, often tiring out four horses of my own in the course of the ride.

This experience did not last long, and served mainly, no doubt, to whet my appetite for adventure. My greatest pleasure was in wandering over the mountains in the country that is now bounded by the two lines of railroad running into Los Angeles.

At that time, the great wagon trains of bullion were coming in over the deserts from old Cerro Gordo. Along this route, I explored and hunted, often alone for weeks at a time. For sharpening the perceptions and enabling a man to concentrate his mind for hours on one thing without change, I believe a certain amount of solitude is necessary.

During this time, I came in contact with many of the old Indian fighters from Arizona and saw the famous General Crook. He chatted kindly with me and set me afire to reach the still little-known frontiers of Arizona and old Mexico. At this period, the career of the bandit Vasquez held a place in the attention of California similar to that once enjoyed by Captain Kidd on the Atlantic Coast or Jesse James in the West. On one of my hunting trips into the Tejunga when I was a boy of thirteen, I had staked my horse for the night in a little side canyon near my camp. About four o’clock in the morning, I left camp to watch a water hole for deer. Coming back after sunrise, I found that, while I was gone, someone had stolen my horse. Noticing the marks of small boot heels, I concluded that the thief was a Spaniard or Mexican; there was also evidence that the horse had been taken only a few minutes before my return to the camp.

The horse trail out of the canyon made a great bend. By climbing a steep ridge and running hard, I believed I could cut into the canyon again and reach the trail ahead of the horseman. So I climbed and ran desperately for two miles and reached the canyon probably not more than five minutes behind my horse and his new rider. Much chagrined, I slipped along the trail until I saw by the tracks that the horse was now being urged to faster speed than his usual running walk, so that I must abandon all hope of catching up with him. I then turned aside at a wood-chopper’s camp. The Mexicans there had seen my horse and told me it was Vasquez who rode it. This did not tend to lessen my indignation, and had the famous Vasquez been five minutes slower, he would have been popped off his mount as quickly as any common horse thief.

From this time on, I nursed my grievance and felt a lively personal interest in the exploits of the bandit, who was then using Los Angeles as his base of action.

Not long after this, my friend Arthur Bent and I were walking along Figueroa Street, intending to go swimming in the xanca near by. Incidentally, most of the townspeople drank water from this same reservoir, but that was of no concern to us. The day was hot; the dust deep. We saw a farm wagon jogging slowly along. On either side of it rode armed men so covered with dust that we could not recognize any one. Inside the wagon, on some straw, lay a man with bloody clothes. Another knelt, fanning the wounded man.

Arthur exclaimed, “I’ll bet they have caught Vasquez!” The officers would not tell us, whereat our suspicions increased. We forgot all about our swim in the xanca and trailed along in the dust after the wagon until we reached the old adobe jail on Spring Street. There we learned from the jailer, Mr. Clancy, that it was indeed the great Vasquez. We had the scoop on all the other boys and felt tremendously important over it. Clancy had a warm spot in his heart for boys and told us fully how the posse had cached in an old ox cart and had impressed the Mexican driver to take them up to the adobe house of Greek George, on the La Brea Ranch; where, as Vasquez jumped out of a window, the posse shot him full of holes before he could be captured. A jealous woman had betrayed his whereabouts to Sheriff Rowland.

Vasquez was taken into a large, comfortable room in the jail, and surgeons worked over him conscientiously for six weeks to get him into prime condition for hanging. This event came off in San Jose — the scene of his first killing. He would have needed a neck as long as a giraffe’s to be hanged in every hamlet where he had snuffed out a life. While he was in the Spring Street jail, Clancy let a few of us boys in to see the celebrity. On one of these visits I asked Vasquez about my black horse which he had stolen in Tejunga and told him of my effort to cut him off. He assured me that he would not have taken the horse if he had realized it belonged to me, and laughingly added, “I will give you a better horse. Ride mine now. Some day you will be a great robber like me — but never trust a woman.” To my immense satisfaction, Sheriff Rowland let me ride Vasquez’s pinto horse around Los Angeles — sweet balm for the wound I had suffered in losing my own.

I have still in mind a boy’s vivid picture of Montgomery Queen’s circus in Los Angeles — still to me the greatest circus ever on earth! On its departure, a lot of us started violent circus stunts of our own. At that time, there were still big sycamores along Aliso Street, where we held forth, walking the tight rope and training our livestock to startling feats.

An old fellow who came to look on at our performances confided to me that he had been a scout — an intelligence officer under Zachary Taylor in the Mexican War. He showed me with sand and corncobs how forts were built “according to Vauban.” Sober, he was a most taciturn man, but when plied with liquor he became very communicative and would recount amazing adventures I cultivated his friendship and naturally sought him in his expansive moods. He became a hero in my boyish mind, and I fed on his tales of fighting and scouting.

One day when he was very drunk, he got into a terrible fight on Alameda Street with another powerful man who finally threw him and started to beat out his brains with a cobblestone. I stood by so paralyzed with horror and fright that I never thought of doing anything to help. Suddenly Juan Abbott, a boy about my own age, rushed by me shouting, “Won’t you help a friend?” He dashed into the scrap and pulled off the man with the cobblestone. Twice this aggressor jumped up to attack again and twice Juan tripped him. Meanwhile my old soldier friend, covered with blood, made his escape. My humiliation was intense. Juan had saved my friend while I had played a miserable, cowardly part in the affair. That query of Juan’s, “Won’t you help a friend?” burned into my brain like a hot iron and I believe has caused me to act quickly many times in later life when help was needed.

There came a time when I realized that I must have some education, so, when an uncle living in the Middle West sent for me, I set forth, at the age of fourteen, and landed in a little town on the banks of a great river. Lest my statement about its good people should even now wound their feelings, it shall be called Montville. It was a flesh-and-blood replica, including the cuticle, of many little Puritan villages, but without the broader vision which New England communities acquired through having as citizens retired seafaring men or men of wide affairs from such places as Boston or New York. The town was just old enough to have lost its rugged pioneers and Indian fighters and had become a strange combination of materialism and intolerant religiosity. When the inhabitants were not trying to reform one another, they were wholly bent on making a lot of money. In this town I remained long enough to get one year of schooling.

In order to carry on any sort of normal boyish activities, it seemed necessary to lead, not merely a double life, but a quadruple one. Sunday was an awful day. No one dared swim in the river, fish, or go boating. Baseball or football on that day would have led to immediate arrest. The youth of the village were like steam in a boiler with a big fire underneath and no safety valve. They were at the point of explosion, and I was the ready firebrand. I offer my apologies to-day to the mothers of that village for completely shattering their nerves. What with the fleet of dugout canoes built by the Trappers’ League and our secret Indian Tribes formed for special raiding, those women never knew what might happen next. A strange new cult was introduced as a substitute for the Sun Dance of the Indians. We hardened ourselves by lacing each other with hickory or hazel switches until we were able to take any ordinary flogging without moving a muscle or shedding a tear. We made moccasins, dug caves in the sand pit, bought twenty-two pistols, got hold of several rifles, waged war on the paper-mill gang, and carried on other momentous affairs too numerous to recount now.

Through all this nonsense, matters were coming to a real crisis with me. Games began to pall. I felt an urge to do bigger things. I had my own living to make, and I realized that the dreams of great African adventures that I had secretly dreamed from childhood could not yet be made to come true. My numerous relatives all wanted to plan my life for me, while I had definite and different ideas of my own. The consensus of opinion was that I should have a strong-handed guardian who would see that every hour of my day should bring its appointed task and who would give constant attention to my spiritual instruction; that I must abandon all connection with the “Tribe” and adopt what would be, for my nature, the equivalent of a monastic life. I conscientiously tried this for a time, for I was under moral obligation, as well as financial, to repay to my uncle the cost of a year’s schooling and my transportation from California. I was then started out on a commercial line about as fitted to my taste and talents as composing music or making lace would have been.

I cut the knot of all my difficulties by taking to the great river in a canoe, one dark night. Then, abandoning the river, I headed for the plains — the Southwest and Freedom.

CHAPTER II

FIRST LESSONS IN SCOUTING

WITH my ruling passion for life in the open and for the wild and beautiful in nature, no charm could hold me long against the lure of New and Old Mexico and Arizona — fascinating regions then on the outskirts of civilization and with a picturesque life of their own, now past and done with.

It was on the frontier of Arizona that I met the man who first gave me definite instruction in scouting. His name was Holmes — a peculiar and erratic character who had served under John C. Fremont, Kit Carson, and other great scouts. He was an old man then, and physically impaired, but his mind was exceptionally keen. He was given to moments of violent temper and seasons of moroseness; largely the result, I believe, of certain terrible sufferings he had endured in the deserts of Altar, in Mexico.

Fearing his end was not far off, and having lost his entire family in the Indian wars, he was desirous of finding someone to whom he might impart the frontier knowledge he had gathered throughout his long life. He chose me, then a boy of eighteen, as his companion and pupil. For six months he took me into the mountains of Arizona, New Mexico, and Sonora, Mexico, and with infinite patience taught me the details of trailing and hunting that make up a scout’s work.

He impressed upon me that in the performance of even the simplest thing there is a right way and a wrong way. This truth he applied to such things as putting on or taking off a saddle, hobbling a horse, drawing a nail, braiding a rope, tying a knot, making a bed, protecting one’s self from snakes or from forest fires, from falling trees or from floods. He showed me how to ascend and descend precipices, how to double and cover a trail, how to time myself at night, how to travel in the direction intended, and how to find water in the deserts. All this instruction was given with endless detail. We spent hours around our camp fire at night while he related tales and incidents, all bearing on the scout’s life he had led from boyhood. Much of this information, unfortunately, I could not absorb, but many of the golden grains he so patiently offered me I hoarded carefully. Many times, in emergencies, his remembered words proved the deciding factor between my destruction and my survival, and I have gratefully given credit to his wisdom whenever I have been able to save lives entrusted to my leadership.

About all that is left in our memory of such old pioneers are some of the more dramatic incidents in their careers, but I feel that it would be of more real interest and importance to us to recall their methods of meeting their problems as they arose day after day and the deep romantic and philosophical ideals wherein they entrenched their hearts. Such characters are worthy to be remembered as long as the nation endures, not only for what they did, but for what they knew and thought.

In Prescott, Arizona, I met another old scout named Lee, who taught me many things. He had a prospect down in the Santa Maria country, and wishing to get some samples for assaying, he took me along with him. It was a rough desert land of wide mesas covered with boulders or lava and cleft by tortuous canyons hundreds of feet deep. At the bottom of these canyons were small streams making deep holes under the cliffs, never touched by the sun’s rays. The trout in these holes were almost as dark as the basalt walls that held them. Along the shoulders and benches, protected from the cold winds of the mesa, grew acres of mescal; and in among the rocks and boulders was much gramma, or bunch grass, with here and there clumps of cedar and many desert shrubs. To hunt the wily Apache in such a labyrinth was no easy task.

Lee was one of General Crook’s scouts, and his success in locating these bands of hostiles was due to his intimate knowledge of their mode of life, and especially of their method of preparing mescal. This is a species of aloe with a heart about the size of a very large turnip. It is the duty of the squaws to gather the mescal, trim off the thorny leaves, and pile bushels of the hearts into great mounds of boulders on which a fire is kept burning for about five days. The heat of the boulders gradually roasts the mescal, bringing out the sweetness and nourishment. These baked hearts are then patted out in cakes, dried on racks of small cedar poles or willow sticks, and made ready for carrying in fibre bags or rawhide lacings. They taste somewhat like baked turnip, but are sweeter even than sweet potato. They are very nourishing, but are full of fine fibres which the Apache chews and spits out, much as sugar cane or sorghum is eaten and disposed of by the negroes. It is also a custom of the Indians to gather each year one big pit full of mescal to be fermented into a strong drink, called tiswin, and to wind up the harvest season with one grand, glorious drunk.

Lee had made a careful study of the air currents that sweep through the deep canyons, and although the Indians found ways to conceal the tell-tale smoke clouds, they could not prevent the odour of burning mescal from hanging in the air and drifting for miles up and down the canyons. By tracing these odours, Lee could mark the most secret hiding places of the Indians. As they could not delay the harvest of the mescal or be content to live without it, they were inevitably spied out by him, then surrounded by government troops and captured. Sometimes the odour of the mescal could be detected as far as six miles from its source. The chewed fibre was another evidence to the scout of the whereabouts of the. Indians; but if the Apaches were suspicious of pursuit, they would not drop a single thread of mescal and would step from boulder to boulder, leaving so faint a mark on the rocks that only the most highly trained eye would ever notice the trace. With a little dried venison, beef, or horse meat and his roast mescal, the Apache seemed to be supplied with a balanced ration. On this slender fare, as frugal as that of the Bedouins of Arabia, they managed to lead their enemies a maddening chase and to inflict many defeats.

It is imperative that a scout should know the history, tradition, religion, social customs, and superstitions of whatever country or people he is called on to work in or among. This is almost as necessary as to know the physical character of the country, its climate and products. Certain people will do certain things almost without fail. Certain other things, perfectly feasible, they will not do. There is no danger of knowing too much of the mental habits of an enemy. One should neither underestimate the enemy nor credit him with superhuman powers. Fear and courage are latent in every human being, though roused into activity by very diverse means.

If, as a nation, we had the courage to write the pages of history as the events really occur, there might be some changes in value very startling to our cherished beliefs; but many errors are so firmly planted in the public mind that it is sacrilege to disturb them, and where they are harmless, it is probably better to let them rest. The idea that the Sioux Indians could fight the modern soldier without any training is an error of the same cloth as the recent pronouncement of the late William Jennings Bryan that “an army of a million men can leap to arms between the rising and the setting of the sun.” Armies are not made in that way. The old Sioux warriors who pitted themselves against such generals as Custer, Reno, Miles, and Crook all passed through much preparatory training. To begin with, they hardened the body systematically. They controlled the mind and set it on a definite object unswervingly. They well knew the uses of both love and hate in all their shades and degrees. Around the council fires, traditions and tales were poured into the ears of the Indian boy until the time arrived when he demanded to become a warrior. Each spring, a class of candidates would come before the medicine man for physical examination. If not strong enough, the youth would be sent back to the care of the squaws for another year. Those who passed the tests were put in close training, both mental and physical, until, on some clear, sunny day in June, the whole clan or tribe would gather on a slope of the prairie near a stream and pitch their tepees for the Sun Dance of the young braves.

When the exhausting test was ended, the youths were carefully tended by the squaws and nursed back to full strength in a few days. They were then passed over to the hands of older warriors for training with bow or gun, lance and horse, and in all the intricate lore of the plains. When they became proficient, they were divided into bands and sent to ambush each other’s horses and equipment, also to manoeuvre on a large scale under the orders and eyes of the great chiefs. If to the qualities and training possessed by these men had been added modern artillery and weapons, one would hesitate to guess how many of our troops would have been necessary to conquer them.

In the literature of the West, the hero, bad man, or sheriff is usually endowed by high Heaven with superhuman powers and has not found it necessary to go through long dreary months and years of training, like ordinary mortals; but I have never, in my experience, met either savage or white man whose natural traits without careful development would have made him distinguished. There are, however, great differences in ability, even among Indians. Those who become famous add to their natural inheritance long training in many things, especially in the hardening of the mind and body to stoical endurance. The great Indian chiefs were men of iron will as well as iron bodies.

I have often thought it would be well for the nervous European to cultivate a little of Oriental calm and self-control and with “Kismet” as his password, relax both mind and body at times and learn to sleep soundly even in the midst of danger. Lord Roberts had this rare power, and it was one of the things that enabled him to devote forty-one years to the service of India and at the age of sixty-eight to take active command of a great army in a new field. In the anxious hours when all Europe seemed combining to wage war on England, Lord Roberts could retire to his camp wagon in the midst of an action and sleep dreamlessly for six hours. To sleep at will is a fine art.

I have often been asked how it happens that I neither drink nor smoke. My answer is that both liquor and tobacco have their uses, but I am of a nature that has never required a stimulant or a sedative. As a scout, I needed all my five senses and every faculty of my mind at highest efficiency at all times. There is nothing that sharpens a man’s senses so acutely as to know that bitter and determined enemies are in pursuit of him night and day. In many lines of endeavour, errors may be repeated without fatal results, but in an Indian or savage war, or in a bitter feud, one little slip entails the “Absent” mark for ever against a man’s name. I recall one scout who forfeited his life by his neglect for one instant to keep in the shade of a small oak tree. He was safe from sight so long as he kept in its shadow, but he became so intent on using his field glasses that he allowed a shaft of sunlight to betray him to the enemy.

The senses and actions of every animal, bird, and insect, if studied, can be made to pay tribute to our store of human knowledge, and our own rather dull wits can be wonderfully informed. Solitude intensifies the perceptions. The herd with a thousand eyes trusts itself to a solitary sentinel with only two. Yet there comes a point where solitude, which entails total repression of the social instinct, turns upon its victim and destroys the alertness of brain it has built up; when, like a great wave, it uplifts only to engulf. I have met solitary sheep herders in the West whose eyes clung to the ground and who mumbled unintelligent words for hours at a time. Solitary confinement in prison brings insanity. Over-trained athletes become muscle-bound, and solitude in excess may make one thought-bound.

I am sometimes asked how it is possible for a scout to live for months in an enemy country, and how horses can travel the astounding distances they do. A volume could be written on the training of a scout — and many volumes have been written on the care of horses. In every country, food can be found if the scout knows how to get it and if his stomach will lend itself to such adjustments as are sometimes necessary. When changing from a cereal diet to one wholly of meat, there is usually a terrible craving for bread that may last for six weeks, and when living on cereals alone, there is likely to be a constant desire for meat or fats in some form. But man’s stomach, like his hand, can be trained to adapt itself to many strange uses.

In the Arizona days, one of our favourite ways of preparing food for long hard rides without fire in dangerous country was to dry venison and grind it to a powder, then mix it about half and half with flour and bake in a loaf that would fit our cantenas or leather saddle pockets. Ten pounds of this concentrated food would, at a pinch, last a man ten days and keep him in strength, albeit lean and hungry. In the North, the great stand-by of Indians and trappers is pemmican. This is dried meat, finely powdered and put up in animal fat. In the Boer War the iron ration given us was made of four ounces of pemmican and four ounces of chocolate and sugar. On this, a man could march thirty-six hours before he began to drop from hunger. All American frontiersmen are familiar with the Indian’s bag of parched corn and with pinole, a Mexican preparation of corn differing but slightly from the “johnnycake” of Colonial times.

In Africa, even in the tropics, one can live very well on a diet of three parts milk to one part fresh blood drawn from cattle. This ration, with a little biltong, enables the Masai to raid a thousand miles. Camel’s milk, goat curds, and dates give to the Bedouin of the desert his wonderful endurance. In the jungle of the Ashanti, the native survives on nothing more nourishing than bananas, yams, and fruit, but he is no match for the man of the desert or the meat-eaters of the high veldt.

A scout knows that a horse can thrive on most of the food that man eats, even cooked food. One of the reasons why I was sometimes able to outride the cowboys and frontiersmen of the West was that I gave infinite care to my mount. In Alaska and the Klondike our horses would eat bread, all kinds of dried fruit and vegetables, crackers, sugar, prunes, raisins, candy, syrup, even bacon, dried meat, and dried fish in very small quantities. They also ate raw eggs when obtainable, dried milk, and other things not ordinarily thought of as fodder. The twig ends cut from willow and cottonwood give roughage and some strength. In the deserts a man may save his mount by gathering the fig-like fruit from the tops of the Pitaya and Sajaura. The “Spanish bayonet” also has a good fruit. Horses will eat crushed mesquite beans, acorns soaked and ground, and other desert shrubs and seeds in season. There are bunches of gramma and other grasses clinging to the cliffs that can be gathered for the scout’s faithful friend in time of need.

Water is sometimes found in deep, almost impenetrable canyons. It can be carried to the horse in a hat, a Navajo blanket, a piece of good canvas, or a bit of rubber cloth. If none of these is at hand, it is well to remember that a saddle blanket will absorb a gallon or two of water, and by turning it over and over in a ball as one walks or climbs, not much will be lost, and the greater part of the water collected can be wrung out into a hat or a cavity in the rock. If there is no rock at hand and the ground is sandy, the procedure is to mix some stiff mud at the water hole, carry it up to the horse, dig a hole in the sand and line it carefully with the mud; then soak the blanket or even one’s clothes and wring the water into this improvised bucket. The horse will drink it gratefully. He can also easily be taught to drink from a canteen or bottle.

In timbered country at night, if bitter cold, a camp fire saves the horse as well as the man. Once, several of us were caught in a terrible blizzard in the Panhandle of Texas. We happened to have some green buffalo hides and we tied some of these over our horses. The skins froze as stiff as boards, but the thick hair saved the team, as other similar skins saved us, although many experienced plainsmen and their stock perished in this same storm. It is always well to save the strength of one’s horse for that one last mad gallop which may mean success after long days of struggle, or escape when all seems lost. Nick Cavarubbias of California was one of the best judges I have ever known of the strength and mental power of a horse. He was the man who first taught me to look a horse in the face as I would a human and leave the search for obscure blemishes to the veterinarian. Courage and endurance make up for light weight and other defects. Many years later, in the Boer War, this schooling in the selection of mounts enabled me to make a three-day raid into the enemy country with a force of Colonial troops and bring back a great herd of beef cattle sorely needed by the main army, as well as many remounts and some prisoners. It was our horses that enabled us to accomplish the impossible.

CHAPTER III

THE TONTO BASIN FEUD

MY ABRUPT escape from my youthful perplexities at Montville was followed by a period of glorious wandering into Missouri, Kansas, Texas, and Mexico. For part of that time, I was joined by a Montville boy, Homer Blick, whose sister had been my boyhood sweetheart. His people had migrated farther west, and, after a while, Homer and I rode together from the cow country to see his new home. The schoolgirl sister still remembered me, and when again I rode into the wilderness, there was much in my heart to disturb my plans for the future — but I rode alone and far.