8,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Ship to Shore Books

- Kategorie: Fachliteratur

- Sprache: Englisch

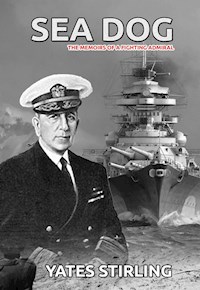

Sea Dog is the autobiography of Rear Admiral Yates Stirling, Jr. (1872‑1948), a long-serving naval officer noted for his controversial views on a variety of subjects, and his outspoken defense of them. His memoirs cover a broad swath of naval history from the late nineteenth century leading up to World War 2—the Philippine insurrection in which the United States was embroiled on the heels of the Spanish-American War; America's involvement in China between the World Wars; naval bureaucracy and politics; and mundane but fascinating matters such as target practice at sea. Sea Dog offers a unique perspective on key historical events and is a must read for students of naval military history.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

Sea Dog

Yates Stirling

Published by Ship to Shore, 2021.

Copyright

––––––––

Sea Dog: The Memoirs of a Fighting Admiral by Yates Stirling. First published in 1939.

––––––––

Revised edition published by Ship to Shore Books, 2021.

Table of Contents

Title Page

Copyright Page

1 – Laying the Keel

2 - The Launching

3 – Commissioned

4 – The War With Spain

5 - The Philippine Insurrection

6 – River Warfare

7 – Staff Duty

8 – Around the World

9 – At the War College

10 – Submarines

11 – The Bridge to France

12 – In the Fleet

13 – The Yangtze Patrol

14 – Washington

15 – Our Friends The Japanese

16 – The Massie Case

17 – My Last Command

18 – Troubled Waters

19 – America at the Crossroads

Further Reading: Dawn Like Thunder: The Barbary Wars and the Birth of the U.S. Navy

1 – Laying the Keel

When I was old enough to think in terms of the future, no other career than the Navy entered my mind. This was but natural, as my father was in the service. I was about twelve years old when such thoughts became active. I told all my companions that I would become a naval officer. I think this gave me increased prestige among them, for they thought of the Navy as something mysterious and exciting.

I was then red headed, though in after years my hair turned to a darker shade. Naturally, I was called “Reddie.” I had a reputation of being a fighter. I did have many fights though I was not quarrelsome nor a bully. My inclination was always to avoid a fight. I believe that my evident desire to keep out of physical combats brought me into fights with other boys, that, with more of a show of assertiveness, might have been avoided. I was slow to anger, and this was often interpreted for fear.

I can recall a host of fights with boys at school and with neighborhood boy gangs where I lived, in the northwest section of Baltimore. I was agile and strong and knew how to handle myself when once aroused. I remember very vividly one boy in our school who gave me considerable annoyance. I saw by his attitude that he was determined to pick a fight with me, and I did my best to shun him. He was by nature a bully; I had seen him fight and knew he was good with his fists. I found myself fearing him, and that feeling caused my pride to suffer. I would go out of my way in order to avoid him. He was the leader of a type of boys who hang around a bully. I was finding it harder and harder to keep out of his way and realized that sooner or later I must fight him. My heart always skipped a beat whenever I saw him.

One day I was returning from school alone. When I was only a few blocks from my neighborhood, I saw this boy and a half-dozen others coming from the other direction, and I knew that I could not avoid him. The bully suddenly confronted me and began to criticize me. I remember he called me a gentleman. He seemed to think that was something to be ashamed of. The usual fighting epithets were passed between us. I confess I was both confused and scared. Then he challenged me to fight him. I must have seen that a fight could no longer be postponed. My red-head temper suddenly flared forth; I told him to put up his fists and sailed into him, getting in the first blow on a vital spot in his face. He was the most surprised boy I have ever seen. I beat down his guard and struck him so many hard blows that he gave ground at once. I followed him and, as the boys say, beat him up unmercifully. Fear seemed to lend me strength for he was bigger than I. When I realized that I had mastered the bully, I became a most elated youngster. Now I was enjoying the fight. Then he turned and ran, saving his face by yelling: “Cheese it, the cops.” I looked around and there was not a cop in sight. I did not follow him, nor did his gang. I was surprised when the bully’s companions gathered round me and said that I was now their leader.

Beating the bully lifted a heavy weight from my mind. My morale received a decided boost. However, my victory, instead of stimulating a desire to fight, had the opposite effect. I found myself hating physical combat as much as ever.

Being the son of a naval officer, I was made captain of a military company organized in our neighborhood. I wore my father’s old sword, and its possession enhanced my importance in the eyes of my companions. Our company, armed with wooden guns, engaged in frequent combats with other companies, many bruises being exchanged, and many wooden guns broken. I once had my sword seized and carried off by a rival company, which was a great mortification. We managed to retrieve it after a fight in which we drove off our opponents.

My father settled his family in Baltimore where his father had always lived. I was then about four years old. I think I was about seven when I first saw a warship. Several of them were in the harbor for some historical anniversary, and the captain of one of the ships invited my mother to bring the children to luncheon. I was much impressed. The ships were spotlessly clean, and the sailors took charge of me and showed me over the ship. Some had sailed with my father. A salute of twenty-one guns was fired, and I remember the women were all frightened at the noise. The guns used in the salute were the big broadside guns of the old frigates, that made a great noise and quantities of smoke. An officer walked from gun to gun counting and ordering “Fire,” until the number was reached. A very vivid recollection is hearing an altercation between the admiral and the captain in which their voices were raised to what I considered an angry pitch. The admiral told the captain: “Carry out my orders, Sir, and don’t question them.” The captain answered: “Aye, Aye, Sir.” Then he saw me looking on with wide, frightened eyes and, turning to the admiral, said: “This boy is Lieutenant Commander Yates Stirling’s son.”

The admiral patted me on the head and in a changed voice said kindly: “Are you going in the Navy, too?” I answered, smiling and much relieved, for I had never heard grown men quarreling before: “I hope to, Sir.”

My home life was always happy. My mother was an incredibly beautiful woman and was always much admired. Although most exacting, she gave her children great affection and every care. She was most ambitious for us all and constantly stimulated our young minds to read good books by reading aloud to us. She was especially ambitious for me, at first, and for some years, the only son among three daughters; and she spent much of her slender allowance on private teachers to cause me to skip grades at school. I am afraid I did not always fully co-operate. I was not a good student.

Years back, when my father was ordered to sea, he was quite sure of being away from home for three years. Warships at that time were just emerging from the days of sail. Steam frigates and corvettes made up most of the navy list. On long passages, sail invariably was used, and many months were occupied in crossing the vast expanses of oceans. Steam was raised only rarely. Ships steamed when entering and leaving port and to avoid too long a stay in those tropical areas called the “doldrums.”

I was about twelve when my father left us to join the frigate Lackawanna in the Pacific Ocean. I remember bidding him a tearful goodbye at the railroad station. I recall two of these sad departures and two glad homecomings after three years’ absence. While he was on sea duty in far-distant seas, our only knowledge of my father’s welfare came in bulky letters that arrived in bunches, sometimes at long intervals, and in which the whole family shared, including my father’s father and his numerous brothers and sisters, all older, for he was the youngest son and greatest favorite. These letters stirred within me a strong desire for a naval life. My mother always read them to us aloud. They were full of most exciting details of his life on a warship: gales, tropical coral reefs, savage people, hunting, and yellow fever. Father’s Chinese steward died of yellow fever when the ship was leaving Callao, Peru, for Australia, and we did not know for nearly six months whether father had caught the plague or not.

His return from one of these long cruises in a far-distant ocean was a great occasion; not only because of our great affection for him, but also because of the wonderful collection of treasures he brought back. One by one they came out of boxes and numerous sea chests reeking with pleasant Oriental odors. He always had appropriate gifts for the family and for numerous others. I shall never forget when a box arrived, brought by two sailors in a cart. In it was father’s dog Tom and a monkey that had been taught to ride on the dog’s back. My mother was always given jewelry and my sisters silks and fans. I remember there was a cabinet in our parlor filled with all sorts of barbaric things collected from the islands of the Pacific. There was also an Indian head from Peru out of which all the bone of the skull had been taken through the neck, and the head shrunk by drying to the size of a large monkey’s head, with long hair, but with the likeness of a man preserved.

On one of his long cruises my father bade goodbye to my mother, his daughters, and two sons. My young brother was then about three. He died of diphtheria a few months later, and another son was born shortly before that sad event. When my father returned, the new son was about the same age as the son he had left behind. I sometimes think it was hard for him to realize that he had lost one son and gained another.

I met many naval officers from time to time. It seemed they were always dropping in during my father’s absences at sea to tell my mother that they had seen him and that he was well, or to bring some small package he had sent from some place in the antipodes. When father returned from sea, he was usually stationed in Washington, either at the Navy Department or the Navy Yard. He would commute from Baltimore, and sometimes he would take me with him to spend the day. In that way I absorbed a lot of the Navy and knew all his most intimate friends.

I recall how delighted I was when my father was given command of the receiving ship Dale at the Washington Navy Yard. It was a housed-in old sailing ship where enlisted men were quartered after enlisting and until they could be sent to seagoing ships. We rented our house in Baltimore and moved to Washington. We all lived on board the Dale, which was fitted up most comfortably for our family, although the cabins seemed ridiculously small after a house. I was then going on fifteen and rather venturesome. The sailors rigged up a sailboat for me, and I spent much of my time when not at school on the river. At the Navy Yard, I was thrown in with many naval boys, sons of officers, and I learned that all hoped to go to Annapolis, about which they seemed to know more than I did. I went to school at “Baldy” Young’s on H Street and insisted on taking the studies prescribed for those who were contemplating entering the Military Academy or the Naval Academy.

My father took me to the White House to see President Grover Cleveland and asked him for an appointment to the Naval Academy for me. The President gazed down at me benignly from his superior height and said to my father: “Why, Commander, your son looks too young to go to Annapolis this year. Maybe next, it will be possible. Shall I have his name put down for an appointment then?” Although fifteen, I was still dressed in short trousers, which was a mistake on our part.

The next year, through a Congressman friend of the family’s and a frequent skating companion of mine on the Potomac River, I managed to obtain an appointment. This Congressman could not find in his district a boy willing to go to the Academy; so, the appointment could be filled by the Secretary of the Navy. The Congressman wrote a personal letter to the Secretary asking him to appoint me, and it was done. I reported for examination at Annapolis in early September 1888.

I shall never forget how superior I felt when, after the lists were posted of those who had failed in different subjects, I saw my name did not appear. I soon entered the Naval Academy as a plebe.

Today, my memories of Naval Academy life during four years of mental grind are considerably blurred. I lacked fundamental grounding in the various basic subjects, but, even worse, I had not formed the habit of close application and was much keener for games and pranks than for my studies. At times, however, things seemed easy enough, showing that after all my brain was sound but that it needed much disciplining.

Probably, the more lasting memories of my cadet life were concerned with pleasant things, such as athletics, summer practice cruises, and “June Week,” when Annapolis is in fiesta and large numbers of young girls arrive to gladden the cadets after their year of hard study. “June Week” ends with a ball, or “hop” as we called it, given by the new first class to the graduating class. During this week, the Board of Visitors, comprised of well-known and important people, witness the drills and all student activities and report in detail upon ways and means for needed improvements and changes. The diplomas are given on the last day of this week, usually by the Secretary of the Navy, but sometimes by the President of the United States himself. This occasion is always to be remembered.

Hazing, during my time, was up for interdiction by the authorities, but except for an occasional court martial of hazers, followed by the dismissal of those convicted, that mild form of student torture of the underdog plebe went on just the same. I came in for my share when a plebe; and after I had become an upper classman, with the vivid memory of what I had been through, I had no hesitancy in passing the same treatment along to the new plebes. I really believe that both the hazed and the hazer enjoyed the experience, and the plebe, in most cases, was better for it. In my time the forms of hazing used could do no harm and often took away an overabundance of conceit from a too-fresh cadet.

The Naval Academy, forty-eight-odd years ago, although possibly owning almost as much ground as today, much of it unimproved, had only one-tenth of the student body of today. Our battalion was composed of about two hundred and fifty cadets. There was one large barracks, housing most of the cadets; the overflow being taken care of in what was called “Old Quarters,” these having been built about the time of the Civil War. The Gymnasium, Armory, and the buildings for engineering, ordnance, physics, navigation, and seamanship activities were brick and of simple architecture. There were many beautiful shade trees and cool walks, and the houses for the officers had wide porches and were almost concealed behind thick ivy vines. While the course in studies gave both theoretical and practical instruction in the newer arts and sciences, much time was devoted to seamanship and the art of handling full-rigged ships under sail. The study of navigation was most complete. The textbooks used, compared to those of today, were most elementary. Electricity was a child in swaddling clothes. Little then was known of the vast possibilities of either electricity or steam engineering. The steam turbine and super-heated steam were still to come. Radio, of course, had not been invented.

For the use of the cadets there were two training ships moored at the wharf on the Severn River. They were the Constellation and the steam corvette Wyoming, both warships of historic memories. The cadets spent every Wednesday and Saturday on board one or the other of these ships at seamanship drills. During the summer months we made a cruise in the Constellation. At the start of our first trip, while skylarking, I sprained my ankle and was sent ashore to the hospital. I thus missed the exciting experience of being shipwrecked. The ship stranded on a shoal just inside the Capes of the Chesapeake. Later in the summer we embarked again.

On these practice cruises the officer that stands out most prominently in my memory is Lieutenant “Karflip” Fullam. He was our tactical officer at the Academy and an instructor in ordnance and gunnery. He wrote the textbook we used. His handling of the battalion in most intricate evolutions won everyone’s admiration. He was most energetic, quick in his movements, and sharp and decisive in his speech. As a deck officer he was a perfect example of a clever ship handler. After we had held our breath in admiration to see Fullam tack the Constellation under full sail through the narrow channel leading into Newport Harbor, he became our class hero, and we dedicated our yearbook to him. Lieutenant W. H. Fullam in after years became a prominent admiral and was superintendent of the Naval Academy about twelve years later, when my brother Archie was a midshipman there.

It is somewhat of a disappointment not to be able to say that I was brilliant in my studies. However, I was moderately athletic and could have been more so if I had not at that time an aversion for any sort of physical competition. I was good at football, baseball, tennis, swimming, diving, track, and wrestling. I attribute my feeling about competition to bad handling of my case by the athletic instructor. He persuaded me to run a hundred yards against the stopwatch. I ran the distance in ten and four-fifths seconds. The world record was at that time ten flat. Then, without giving me training in how to start, he insisted I run against the best cadet runner for that distance. When the report of the starting gun penetrated my thick head, my opponent was, it seemed to me, so far on his way that I felt that I could never close the gap. My feet seemed anchored to the ground. It took all the heart out of me. I thought I was not good enough, and I refused to go into the track meets. I did run the baseball bases and established a record one year.

I was keen about football, but although fast, I was too light in weight. I was captain of the second team and played both end and halfback. I substituted occasionally on the varsity. I wrestled in the gymnasium exhibitions several times.

Naval Academy days were none too pleasant. I resented restraint and strict discipline. Almost every year I accumulated nearly the allowed limit in demerits. I was very careless, and my sins were those of omission. One night a classmate and I had taken French leave, and the watchmen were wise that the cadets were scaling the wall and were on the lookout. When I reached the top of the wall on my return and was poised to jump down the fifteen or twenty feet, there was a watchman waiting for me. I could not stop, so I landed on him. He did not recognize me, and before he could recover, I was out of sight. The next day one of the watchmen carried his arm in a sling. I strolled up innocently, and he told me that it was a collarbone fracture. Years later he informed me he had known it was I all the time, but he had been in my father’s ship at one time and would not report me.

There was a girl in Baltimore whom I had known for years. I imagined for some time that I was in love with her, but I did not consider she felt the same toward me. She was not a beauty and was probably a little flirt; at least she was always surrounded by men, which I have found is convincing evidence of that. On my third class leave, spent in the vicinity of that city, we were constantly together, and I returned, after a month, to the Academy head over heels in love with her. I could not keep my mind on the difficult studies. When I opened my books, my mind strayed off to all the good times I had had, and the girl’s face was always before my eyes. I was in a near panic because I was making bad recitations and had been posted in one subject as unsatisfactory. I feared I would “bilge.” I wrote to me father and told him I wanted to resign as I knew I could not keep up and would be “bilged” in February. He came down from Baltimore to see me. If he suspected what was wrong with me, he said nothing to me about it. I do not recall now what we talked about, but somehow, he gave me the determination to stick it out. Hard study soon made things clearer to me, and I never was on the weekly list of unsatisfactory again.

My mother was skeptical about me. She was forever saying: “I’ll give you just six more months to ‘bilge.’” Whether she thought that remark would rouse my fighting spirit and cause me to study harder, or whether she was preparing her own mind for that disappointing event, I do not know.

At the end of my third year at the Academy, as a first-classmate, we embarked again on board the Constellation. I know that this training in a sailing ship gave me experience in many ways that was useful to me later. The cruise was too short and hurried: only three months; but it seemed to stir in me a latent instinct for the sea. Both my father and my grandfather on my mother’s side had been captains of sailing ships. The first class for this cruise were divided into two details: white and blue. Cadets in the white detail wore sailor clothes and did sailor work. The blue-detail cadets wore their cadet uniforms and performed the duties of officers. My regular detail was mainmastman while in white, but as I was active and experienced, the officer of the deck suddenly ordered me aloft to help with the sending down of the main royal yard.

After weighing anchor in Annapolis, we had started down the Chesapeake with all sail set. There was a squall approaching, and the order had been given to shorten sail and send down topgallant and royal yards. Of course, I was not a beginner in going aloft, but this time the conditions were far worse than I had ever experienced in our sail drills in quiet weather at the dock.

The order to shorten sail was an emergency, for the squall had appeared suddenly and had taken us unawares. Before I had arrived in the maintop the wind and rain were upon us. The royal yard was about one hundred and twenty feet from the deck, reached after climbing two almost vertical shrouds and two swaying Jacob’s ladders. As I went over the maintop platform, I glanced above me and realized I had over a hundred more feet to climb. I began squeezing out tar on every handhold to prevent being blown out into space by the great force of the wind and the pressure of the solid sheets of rain. On the ladders my body swung in and out in teeth-rattling lunges. I was drenched and nearly blinded by the stinging rain in my face.

I felt a sense of security, which was more imaginary than real, when I at last reached the royal yard and swung myself out on the frail spar. Clutching the flapping sail, I planted my feet insecurely on the swaying footrope. When I looked down, shivers went up and down my spine, for then the precariousness of my position was only too evident. One miss in a handhold or a foothold and then? A cadet had followed me, and I could see he too was holding on like grim death on the other yardarm. We used sign language between ourselves and to the deck below.

Exerting every ounce of strength we could muster and while the gale was at its height, we managed to furl the sail and get the yard ready for lowering. Then, holding on at the top of the Jacob’s ladder, we saw the yard cockbill and swing out in space like a writhing serpent. As it was lowered, I followed it with my eyes, guiding it by the mast rope and prepared my nerves for the descent, which would be quite as dangerous as the ascent; but at least gravity would be in our favor.

When I reached the deck, I felt, I imagine, like an aviator after his first solo flight. I would have willingly turned around and gone through the experience again. Before the cruise was over, I know we all took going aloft in any weather in our stride. The physical condition and the confidence acquired that enable you to hang, without batting an eye, by one hand in space with a yawning drop below you are things the modern sailor never attains. That sense of exaltation was well worth the price paid.

The blue detail spoken of above throws a cadet on his own. Each had to maneuver the ship under sail. No one knew when he would be called to the ship’s bridge, handed the speaking trumpet by the commissioned officer of the deck, and told to perform a maneuver. One day I was leaning against the mainmast when I heard my name called by a bull-throated boatswain’s mate, for me to report to the officer of the deck. I was in white detail and I wondered: What have I done now? When I reached the bridge, the officer of the deck handed me the trumpet and said: “Mr. Stirling, you have been taken aback. The crew are at dinner; bring her back on the wind.”

On previous occasions I had succeeded in tacking, wearing, box-hauling, and bringing ship to anchor, and felt I had performed the evolutions to the satisfaction of the officer instructors who always appeared on deck with notebook and pencil in hand to sit in judgment. But even so, my heart sank at this assignment. I gazed aloft. The sails were all aback. Then I looked over the side and saw the ship was about dead in the water. I asked the helmsman: “How’s your helm?”

“Down,” he replied. The officer of the deck had luffed and put the sails aback.

Looking back today I cannot imagine why I was panicky, but then I was, and for a minute that seemed hours my mind drew a blank. I was absolutely overcome, and if I had followed my inclination I would have run down from the bridge. I saw the eyes of my people below eyeing me questioningly. Then I calmed and reason once more came to my mind. It was the maneuver of “Chapeling ship without touching a brace” that was wanted, described in our seamanship manual. A simple maneuver of using the helm and the movement of the ship through the water to bring her back again on the same tack and without changing the bracing of a yard. When once again the ship was back on her course, I walked down from the bridge much happier than when I had arrived there. I do not think that anyone knew what I had gone through.

After the cruise, when we returned to Annapolis and began our studies again, I began to realize that if I were going to graduate high enough to obtain the coveted commission, I must get much higher marks in my studies and stand far higher in the class than I had managed to do so far. In those days only ten cadets could be assured of commissions, and the additional ones depended upon vacancies made during the year in the list of officers of the Navy. The subjects of study now seemed more to my liking. They were all important to the naval profession. If I were going to be poor in these, of what use would I be as an officer? This thought gave me the incentive I needed to snap out of my mental apathy. After having stood in the forties in my class for three years, I came out at the end of the first-class year standing ten for the year. I found myself just in the nick of time.

A student at the Naval Academy never will feel as self-important again in his whole naval career as when he reaches the exalted position of being a first-classman, more especially if he is also a cadet officer. A cadet officer within the walls of the Academy, and even in “crab town,” as picturesque and historical old Annapolis is irreverently called by the naval students, is a somebody; and he is most conscious of it. The thin gold circles around his sleeve and the star above them give him the greatest assurance and inflate his ego enormously. The cadet officer of forty-six years ago gazed proudly almost every minute of the day at these stripes on his sleeves. Each year he had seen those stripes on the arms of upperclassmen, men whom he had looked up to as being almost gods. Now here he was with these stripes on his own arm.

I had shown certain ability on the practice cruise and was down for two stripes, or cadet lieutenant. But before I could receive them, they had vanished. A boyish indiscretion in keeping a boat away too long on a picnic reduced the award to a first-class petty officer. I became the first sergeant of the first company. The captain of the company was Homer Ferguson, my roommate, and now the head of the Newport News Shipbuilding Company. I remember even now, forty-six years later, my great chagrin at the loss of the stripes. Cadet Jack Myers, who became a well-known general in the Marine Corps, was the cause of my loss. He returned with one of the prettiest girls over an hour late, and I had waited for them. I could not shove off without him. Speaking of the blow this loss was to me, I visited that Naval Academy to see my son Yates, a midshipman, just after the stripes were awarded. I was then a rear admiral. He had written his mother that he had no chance of getting stripes. My wife and several of the girls went with me to see a football game at the Academy. Yates met us at the station, and there were two stripes on his overcoat sleeve. He told us with a smile and a twinkle: “I just borrowed this overcoat.” Knowing he had won these stripes quite compensated me for my disappointment thirty-four years before.

Having the rank of cadet officer gives the privilege of wearing a sword instead of carrying a gun at all military drills. But what is more important still is the knowledge of the impression the stripes make on the galaxy of girls who flock to the Academy from the neighboring cities to attend the social functions given during the year. For that year, a cadet officer also has the freedom of the Naval Academy gate. This gives him an added prestige and a sense of responsibility. He leads his unit in drill and in many ways has more opportunity of becoming proficient as an officer of the Navy.

After enjoying his prominence for a year, and, at graduation, upon donning the uniform of a cadet at sea, the same as that of an officer, he imagines the life of restraint within high walls has gone forever. How sadly he is mistaken! He soon enough finds that he is after all a very minor person indeed. On board ship he will discover that even his freedom has been in a measure curtailed, and that being a first-classman and a striper at the Academy really has a higher relative value and importance than a cadet at sea. He has begun now at the lowest rung of the naval ladder. It is a long, difficult, and often heartbreaking climb, through six grades, to the top, that of rear admiral. That far-distant horizon does not now concern his young mind. His immediate horizons are the four walls of his tiny cabin or the steerage he will share with others. Also, there will be his gun division made up of young men of his age who will salute him and obey his orders, although possibly having more knowledge from a practical standpoint than he will have at first. Then there will be his division officer, who will be his guide, philosopher, and friend, and, his Nemesis if he is too neglectful of the things given out to him to do. Anyway, he is on his way up the ladder, and success or failure belongs to him and no one else. The Naval Academy has given him his start, but he will learn that it is but the starter’s gun and that in winning the race he must rely only on himself and on his use of the qualities that nature gave him. That tiresome waiting to come on every rung of the ladder may try his patience and tend to dim romance. But if he has it within him to rise in his chosen profession, eventually he will succeed in cutting quantities of red tape and free his mind from too much naval conservatism and take up a torch for progress and improvement. But now such thoughts are not his immediate concern. Life lies ahead. He does not fear the future.

Admiral Yates Stirling, Jr.

2 - The Launching

In my day, a cadet upon graduation was not commissioned an ensign. First it was necessary for him to serve two years at sea on probation to show that he was suitable on the practical side. At the end of this two-year cruise as a “past midshipman,” as they were called, a final examination of the class at the Naval Academy was taken to decide the final standing in the competition for commissions. Today, midshipmen after graduating are given their commissions as ensigns when they receive their diplomas.

Soon after graduation from the Academy in 1892, I started for Honolulu, Hawaiian Islands, or the Sandwich Islands as our geographies then called them, to join the cruiser San Francisco. Together with four classmates, I sailed to San Francisco in a British liner, stopping at Honolulu on its run to Australia.

Being ordered to the Hawaiian Islands seemed to me a most romantic adventure. The Islands were not so well known as they are today. I had learned about them from my father, who had been there many times. The Navy for years had been identified with Hawaii, and many of our admirals and captains had been friends of the reigning sovereigns. The picture in my mind of Hawaii was vague but included the beauties of the tropics and sand beaches where the pleasure-loving natives spent most of their lives swimming, fishing, and surf riding. I suppose we were all a little disappointed to find we had arrived in a place little different from home as far as civilization went. There were many Hawaiians in evidence on the streets of Honolulu, also other races, particularly Chinese and Japanese; but there was nothing really different from home except the setting: the tropical trees and flowers in the greatest profusion, the white coral sand beaches, the rolling surf incessantly pounding on the barrier reefs around the Islands, the land sloping back from the narrow fringe on the sea where civilization maintained its existence to the high mountains in the interior.

Hawaiian life even then had merged into Western civilization or Oriental. There were no truly Hawaiian villages. One saw the natives fishing and gathering edible seaweed. Fishing was by means of the spear, with which they were most expert. The natives, especially the women, wore western clothes; the women wore the mother hubbard or Holaku. This garb was not picturesque but, from the standpoint of the missionary, was more appropriate for a Christian people. The scanty attire of the native Hawaiian was tabu. These civilized clothes did not benefit the health of the race. Being naturally strong, they were unaware of the danger to health when wet clothes were allowed to dry on them. Colds and lung troubles developed. Coconut oil, with which it had been the custom to smear their bodies, no longer was used, and omitting this precaution caused many deaths from pneumonia and tuberculosis.

Honolulu was a pleasant change of scene after four years of restraint at Annapolis. Life on board ship was not arduous. There were few drills, and in the afternoon all except those on watch went ashore. The San Francisco had been in Honolulu for many months, and the officers had met many friends. I soon found myself invited to riding and swimming parties and picnics where I met many women of dark skin with British and American fathers and Hawaiian mothers. The women had mostly been educated in England. They were all expert horsewomen and perfect swimmers. I found them most wholesome companions, although I had the feeling that I must be careful not to fall in love. It seemed strange to see a dignified white official surrounded by children with skins as dark as a mulatto.

There was an undercurrent of politics everywhere one turned. The most important subject in all minds then was what nation eventually would succeed in annexing Hawaii. The late King Kalakaua had been partial to America, and we had gone to considerable lengths to retain his favor. The present Queen, Liliuokalani, was believed to favor Great Britain. The Royal Princess was being educated in England. The Japanese, with the subtlety of the Orient, were waiting for a favorable opportunity. They too coveted Hawaii.

All three nations were watching each other to be sure no one would obtain advantage over another and become too powerful in Court circles. Hawaii was known to be an important strategical location with great commercial prospects. The United States would not have permitted any other nation to seize the Islands, yet at that time, the Administration in Washington, under President Cleveland, did not feel itself strong enough to take them for this country. Our method, therefore, was one of watchful waiting and maintaining friendly relations with the Hawaiian Queen and her government.

Our Admiral, George Brown, was a favorite with the Queen. She gave a great ball in his honor. The Admiral and all his officers attended in special full-dress uniform. We marched past the dusky Queen on her throne, making a colorful sight. By taking part in such ceremonies and through the cultivation of friendly relations, the Navy performed its mite in helping diplomatic objectives to be realized.

In the small harbor of Honolulu there were usually at least three warships. An American, a British, and a Japanese were always there to watch their nations’ interests. They reminded one of carrion crows, as they awaited the demise of the tottering monarchy. The Japanese made no secret of their desire to obtain sovereignty over the Islands. Their naval strategists, as well as others, fully realized the future value of this location for commercial usage and as a base for their expanding war fleet in the Pacific. Their easy victory on the sea over the Chinese navy a few years later was then being planned, and their conceit made them certain they could intimidate our country and obtain Hawaii. Japan was building up her navy very rapidly at that time, with the object, as it turned out, of fighting China. Her naval ambitions in the Pacific are thus seen to be of long standing. Even as early as this, war between the United States and Japan was being prophesied by certain writers, among them General Homer Lea.

Great Britain also believed she had a claim to the Islands and would have gladly received them within her empire. Both Japan and Great Britain must have foreseen that someday America would awaken to the necessity of owning the Islands lying so close to its California shores, but hoped that somehow they might beat us to it.

The fear of the American residents of Hawaii that the Islands might be seized by a nation other than the United States was an important reason for the revolution of 1893. Consul General Sewell did hoist the American flag; but Cleveland disavowed it, and the flag was hauled down.

The secret correspondence between Japan and the United States over this incident would make interesting reading. As yet it has not been published to the world. My belief is that Japan’s demand that the United States must not annex the Islands caused Cleveland to postpone annexation until a more propitious date. After Dewey had won the battle of Manila Bay in 1898, that date seemed to have arrived, and we annexed the Islands. Japan made a most decided protest, but that time it had no effect: the nation was at war, and the Islands were needed in our overseas plans of campaign.

I was sorry to leave Hawaii. I have returned several times but never found it as pleasant. Particularly because of the slow change of atmosphere toward that of the Orient. It has thus lost most of its charm for me.

The San Francisco was relieved by the Boston in the fall of 1892 and sailed for Mare Island Navy Yard for repairs. Then we joined the squadron commanded by Admiral Bancroft Gherardi, consisting of the Baltimore, San Francisco, Charleston, and the gunboat Bennington. We were bound for the great Naval Review in connection with the World’s Fair at Chicago. On our way around South America and through the Straits of Magellan we made stops for the purpose of cementing more firmly the good relations between the United States and other countries.

In the Bay of Mazatlán, I witnessed the first target practice of our warships that I had ever seen. It was not particularly inspiring for me. I sat all day in an uncovered whaleboat under a blistering sun, using a graduated T-square to record the angular distance of the fall of shots from a small pyramid target.

After Mazatlán we anchored at Acapulco, a small land-locked bay, intensely hot and celebrated for its man-eating sharks. The evening of our arrival I was visiting the steerage of the Charleston when Father Rainnie, the Catholic chaplain, burst into the steerage and challenged any of us to go in swimming with him. I took his challenge seriously and said that I was willing.

We donned our bathing trunks. The chaplain dove first off the gangway, and I followed him. When I struck the water, all the ghastly stories I had ever heard of sharks came into my mind. I swam swiftly back to the gangway, getting there just as Rainnie reached it. He said, breathlessly: “I don’t think we should put too much confidence in the Lord’s being able to protect us from our own stupidity.”

We both had had enough and scrambled out of the water. The officer of the deck pointed out several big black fins where we had been swimming a moment ago.

At Panama we saw the abandoned canal with valuable machinery left to rust and become useless. Before the ditch could be built, the savage, death-dealing mosquitoes had to be exterminated. De Lesseps had failed because medical science in his time was not far enough advanced.

In all ports at which the squadron stopped: Callao, Valparaiso, and Montevideo, the Admiral and his officers were lavishly entertained by the officials there. These periodic visits, where considerable American gold was spent, were supposed to benefit friendly relations. The year before, Chile and the United States very nearly drifted into a war over the killing of a United States man-of-war sailor by a Chilean mob. Our visit to Valparaiso seemed to smooth out some of the hard feeling against the Yankees. The people of South America seemed to me not at all like our people. They were more like Europeans. As nations they mistrusted our intentions and were jealous of our wealth and power. They resented our interference in their affairs. The South Americans of the governing class, being Latins, are intensely proud but suffer from an inferiority complex. This may be because the race from which they sprang, once conquerors, is now low in the scale of importance in world politics.

The Naval Review was assembled at Hampton Roads, where we arrived in due time. Such a review of course is a show, and a very impressive and beautiful one. All nations parade their best ships. The number sent by the nations depends upon the availability of anchorage space. A review is excellent advertisement for the shipbuilding art. Those nations who depend upon others to build their warships can compare the relative merits of foreign construction and choose where their ships will be built.

Warships at a review, of course, must be open to the public, and naval men of all nations will examine them most minutely. The review offered valuable opportunity to compare types and the individual ship efficiency of all nations. At New York, where the final review was held, there were warships from all the great naval powers as well as from the smaller nations. The great powers represented were Great Britain, Russia, Germany, Italy, Spain, Japan, and France. It was a liberal education for naval men to inspect the different ships and observe how things are done in the navies of other countries.

I was much impressed by the smartness and cleanliness of the British warships. No others seemed as well kept, except for our own. The peculiarities of the French construction and arrangement came in for considerable attention. The appearance of their ships seemed almost grotesque. The Italian ships seemed to be modeled after the British. The discipline of the German tars caused much comment. It seemed so unnecessarily strict.

Ashore, those who spoke a common language seemed to band together and stay together. We saw most of the British for that reason, although fights were often in order. Seeing these different nationalities on shore, ticketed by their characteristic uniforms and their attitude toward discipline, gave one a sudden insight into the reason why there was war. Each nation, as represented by its sailors, seemed to have a chip on its shoulder; each considered himself the better man. These uniformed men typified their nation, each feeling superior to all the others, else insanely jealous of the greater importance of others.

There was some evidence of cordial relations among the sailors because of diplomatic guidance from home. For instance, the cordiality between the British and the Italians, the French and the Russians.

Shortly after the review was over, I was sent to the cruiser Charleston, and soon thereafter we sailed to return to the Pacific coast. We got only as far as Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, where we remained because of a revolution that centered about that great seaport.

The revolution came about through political jealousies between the powerful leaders of the country. The President, General Peixoto, an army leader, had seized power. Admirals Mello and Da Gama were backing the opposition, claiming that their candidate had been elected.

Rio is the capital and the principal port, so pressure was being used there upon President Peixoto to force him to give up the presidency to the elected candidate. But the elected candidate did not have enough guns and soldiers. When we arrived, the two admirals were controlling the great bay and had closed the port to commerce. The Brazilian naval ships in Rio were the battleship Aquidaban, the cruisers Republica, Trajano, and Tamandarey, and many small launches.

At the narrow entrance to the port were two forts, and another was within the harbor but commanded the entrance with its guns. The outer forts were loyal to the government, the inner fort was with the navy. The navy held all the islands in the bay. The army held all the mainland of the bay. Almost every day we witnessed a bombardment between the forts or between warships and the outer forts. Occasionally the Aquidaban would run the forts at the entrance and be absent several days. The firing was fast and furious during these forays and gave us much excitement to witness.

When we arrived, there was a British gunboat and two Portuguese cruisers in the harbor. Our Captain, H. F. Picking, due to his rank, became senior of the foreign navies in port, and by international custom was regarded as the leader in concerted actions. One of the first things to be considered by the foreigners was the question of whether the city could be bombed by the rebel navy. The answer hinged upon whether the city was fortified. Captain Picking sent Ensign H. E. Smith and me to find this out.

We went ashore on this rather difficult duty in civilian clothes, of course, because we could not be identified as American naval officers. If we could discover that there were large guns mounted on the city’s hills, then the city was fortified, and therefore the navy could bombard it under the rules of war. Smith, being the senior, elected to explore the higher places on the hills back of the city, while I started in lower down. Smith was arrested and jailed, and our consul had to go in person to rescue him.

I pretended to be a tourist on board of one of the American schooners in the harbor and made friends with several Brazilian army men, who were most obliging. They openly showed me some large-sized artillery in concealed emplacements, the largest being six-inch Whitworths, firing shells weighing a hundred pounds. They kept me for lunch, and we drank many toasts in some very fair brandy. They were so openly cordial and trusting that my conscience pricked me when, from memory, I sketched for Captain Picking the positions of the guns I had seen. The foreign captains then removed the ban on bombardment, notifying both sides that they considered the city was fortified and therefore not a defenseless city as the government had been claiming. The Brazilian Navy, however, never used its authority to bombard. I was glad of this, for the city was so beautiful and belonged to the navy as well as to its defenders.

To make things more uncomfortable, yellow fever now broke out, or rather became epidemic, and our liberty ashore was stopped. We had only one case, a yeoman who had been detailed for the consul to help him with his correspondence and who slept ashore often. The yellow-fever mosquito at that time had not been discovered. It was then the general belief that the disease was caught by contact with a patient or by inhaling the miasma from the swampy land at night. There was a general exodus from Rio to the mountains to escape the plague. I was often ashore on missions for the captain but never could stay after dark. The yellow-fever mosquito, it later was found, is a nocturnal hunter.

Our boats landed at the marine arsenal, which was in the hands of government troops. Just alongside, with a strip of water between, was the Ilha de Cobras, the Brazilian Naval Academy, which had joined the rebel navy. One day I was at this landing with a steam launch from our ship. I was about ready to shove off and return to the ship when my curiosity delayed me. On the sea wall alongside of which the boat lay there were many soldiers behind sandbags. They were firing at and being fired upon from Cobras Island. A well-dressed man came up to where I was standing, foolishly exposing myself to stray bullets, and said in perfect English: “I am a Brazilian naval officer, an ordnance expert, and have just returned from England. I landed outside the bay from a British merchant ship. I am afraid of being recognized, and if arrested I will be shot. Can you take me out to Admiral Saldanha da Gama at Enchades Island?” I was deeply moved. He seemed such a pleasant individual with charming manners. I gave no thought, apparently, of the consequences to myself. Youth is ever romantic and trusting. I said:

“I cannot offer you asylum, but if you should get into my boat, I could not put you out.” He made a dive for the boat.

Enchades Island is a small island in the middle of the city. I had been there many times carrying messages between our Captain and Admiral da Gama. I knew the water was deep enough for the launch close to the sea wall there. When we approached the island, I told the coxswain to steer close. Our refugee produced a big wad of Brazilian money and wanted me to take it for the crew of the boat. Naturally, I could not accept it.

By that time, the launch was skirting the sea wall of the island of Enchades. “A word to the wise is sufficient,” I said; “good luck.” He showed his gratitude in his eyes. Then he turned and jumped. Upon steadying himself on the sea wall he waved his hand to us and then stood gazing at the boat for some time before turning away.

The following morning the guns of the new warship, Tamandarey, began to shell the marine arsenal and the Nictheroy battery. The enormity of my crime had been dawning upon me. I had given aid to a rebel. The rebel I had aided was now firing at the government my country recognized. I worried for a while afterward over this most unneutral service I had given, because, if it became known to our captain, he would have no other recourse than to order me before a court-martial. However, I have never regretted my action and have often wondered what became of my Brazilian. I did receive word from him once through one of our medical officers who had seen him on board the Tamandarey after an explosion on that vessel when we had sent medical aid.

The war was causing much inconvenience to foreign shipping. There were many merchant ships of all nationalities that had been lying idly at anchor there for months. The war was dragging on with no visible results accomplished by the navy rebels. Foreign nations, principally ours, were becoming restive. This stalemate in the revolution again exemplified the age-old maxim that a navy cannot capture a city nor control it unless accompanied by troops. The navy had no troops. A navy can bombard and terrorize the inhabitants and close the port to shipping, but without troops it cannot secure a foothold on shore.

I have often told that I was under more dangerous gunfire in Rio Harbor during that revolution than during the whole of the Spanish War. One incident I remember most vividly. My launch from the Charleston had landed Spears, a war correspondent, alongside the Aquidaban to interview Admiral Mello, and we were waiting for him. The army had mounted two high-power six-inch guns at Nictheroy, and, while we were stopped close to the side of the battleship, these guns began to fire at her. The battery fired every few minutes. I could see the people on board the Aquidaban take cover behind armor at every flash from the battery, but there was no armor for us to get behind. The shooting was not bad but the Aquidaban seemed miraculously to escape being hit. Many shells struck in the water near us, even throwing water over the boat and wetting us to our skins. I was too proud or foolhardy to move out of range, and we took the grilling for nearly an hour. Fortunately, the shells did not explode. When Spears finally called us alongside, he told me that he and Admiral Mello were all the time in the Admiral’s cabin, entirely unprotected, and that he had wanted to go when the battery began to shoot, but that the Admiral would not let him as he was most anxious for Spears to hear his side of the controversy. I said: “You didn’t have anything on us. We even got splashed.” The Aquidaban got underway as soon as we left and steamed out of range of the battery.

Another time this same battery began firing at a large steam launch of the rebels, and the launch in desperation, for the shots were falling close to her, headed directly toward the Charleston. Most of the time the rebel launch was between the battery and the Charleston, and all shots going over the launch endangered our ship. When the launch reached the Charleston, it dodged behind us. Then, when the launch was hidden behind the massive hull of our ship, the battery fired two shots. They both fell short but perfectly in line, and they splashed water on the boats secured to our lower boom. I have never seen our captain so angry. He even considered opening fire on the battery. Afterward he sent a letter to the government ashore saying if such a thing occurred again, he would open fire on the battery. Those controlling the Nictheroy guns may have been using indirect fire, in which the target is not seen through the gun sight. If not, it was deliberate, for the army had been complaining that the foreign warships were in the way of their fire upon rebel ships.

As the months went by, the United States Government had sent one after another warship to augment our squadron in Rio. Finally, we had the San Francisco, Charleston, Newark, Detroit, and the armored cruiser New York. This concentration, of course, was for the purpose of giving us sufficient force in case it became necessary to use our warships to put down the rebellion.

We now had a rear admiral in command of our squadron, Admiral A. E. K. Benham. Admiral Mello had left the scene, but the battleship Aquidaban remained in the bay. It was a very formidable ship, even stronger than our New York in a fight at such close action.

There had been many rumors. Admiral da Gama was in command of the rebel ships. He had been educated in England and was considered a royalist, anxious to bring back the monarchy to Brazil. I had seen the old royal flag of Dom Pedro hanging on the wall of his office.

One night our ships received the startling signal to be cleared for action at daylight. No one knew why. We knew that the rebel, da Gama, commanding in Mello’s absence, had been in consultation with Admiral Benham for hours that day. There was a rumor even that the Brazilian Admiral had offered to surrender to Admiral Benham. There was a report that the foreign backers of the revolution had refused more money, and without money, the navy’s cause was hopeless.

I am convinced that Benham persuaded da Gama that his cause was lost and that da Gama agreed to give in without a fight. Benham at all events decided that the shipping must move, and the port be opened to world commerce.