9,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

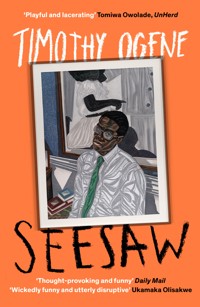

- Herausgeber: Swift Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

'A very funny, intelligent, deliberately and engagingly resistant, and moving piece of writing' Amit Chaudhuri A 'recovering writer' – his first novel having been littered with typos and selling only fifty copies – Frank Jasper is plucked from obscurity in Port Jumbo in Nigeria by Mrs Kirkpatrick, a white woman and wife of an American professor, to attend the prestigious William Blake Program for Emerging Writers in Boston. Once there, however, it becomes painfully clear that he and the other Fellows are expected to meet certain obligations as representatives of their 'cultures.' His colleagues, veterans of residencies in Europe and America, know how to play up to the stereotypes expected of them, but Frank isn't interested in being the African Writer at William Blake – any anyway, there is another Fellow, Barongo Akello Kabumba, who happily fills that role. Eventually expelled from the fellowship for 'non-performance' and 'non-participation,' Frank Jasper sets off on trip to visit his father's college friend in Nebraska – where he learns not only surprising truths about his father, but also how to parlay his experiences into a lucrative new career once he returns to Nigeria: as a commentator on American life... Seesaw is an energetic comedy of cultural dislocation – and in its humour, intelligence and piety-pricking, it is a refreshing and hugely enjoyable act of literary rebellion.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 324

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

Contents

Chapter 1Chapter 2Chapter 3Chapter 4Chapter 5Chapter 6Chapter 7Chapter 8Chapter 9Chapter 10Chapter 11Chapter 12Chapter 13Chapter 14Chapter 15Chapter 16Chapter 17Chapter 18Chapter 19For C. Ogene, SES and JPH

1

Located on the twenty-first floor of the New Tower in the historic centre of Port Jumbo, the Coastal Humanities Club has been around since the late 1950s when it started out as the West Africa branch of London’s Art and Reform Club. The old building, designed by a prominent English architect, disappeared a decade ago, replaced now by the New Tower, a modern high-rise that houses various thriving ventures: hotels, oil services companies, IT companies and a host of e-commerce firms with names as vague as the services they deliver.

I spent the night in a boutique hotel on the third floor, where I busied myself at the cocktail bar, ‘preparing my notes’ for the lecture I was scheduled to give the next day.

There was no need to put me up at the hotel. I lived in the same city. Two bus rides away. But the Club was swimming in money, and I’d long since lost the moral urge to refuse the generosity of those who appreciate my work.

The more I drank the more the title of my lecture changed, from ‘Thoreau as Post-Colonial Example’ to ‘Worlding Walden: The Thoreauvian Stance as Discursive Contribution to Anti-Colonial Thought’.

I’d not read Thoreau in years and I knew little about post-colonial theory. But I’d since perfected a ‘mode’ of speaking that ‘positioned’ me to effectively ‘reproduce’ the ‘forms of knowledge’ that are relevant to the ‘discourses’ of the ‘Global South’. I had a list of catchphrases that I’d harvested from articles in prominent journals and magazines, with the intention of dropping them as ‘signposts’ to ‘foreground’ my legitimacy while ‘unpacking’ the contents of my lecture.

One of the catchphrases, ‘post-colonial psycho-manic modernity’, came from a talk delivered at the same Humanities Club many years ago, by a Pakistani historian, who, as I saw when I looked him up, was now the head of the prestigious Provoost Institute in New York, founded in the early 1960s by a Belgian-American oil baron and art collector who wanted a space for ‘enlightened ideas’ that would ‘illuminate’ a world devastated by the world wars.

The Coastal Humanities Club, which counted the Provoost Institute as one of its ‘global partners’, was itself a society of civilised men, more or less the African descendant of the European Enlightenment, a belated stop in the World Republic of Letters, situated nonetheless in the centre of a city so chaotic Voltaire would have had a hard time thinking.

As I lugged myself down the hallway on the twenty-first floor on the day of the lecture, hungover, feeling the softness of its thick rug, I felt like I was reliving my childhood in the nineties, walking down the same hallway in the company of my father, dragged to cocktail parties and dinners at the Club, enduring talks on the fate of democracy in Africa, by speakers from far-flung places: Cairo, London, Cape Town, Delhi, Istanbul. And in the sixties, when my grandfather served as the Club’s first black president, the talks and lectures centred around the Cold War, and the Club chanted its non-alignment, ostensibly detached from capitalism and communism, but the cases of wine from ‘friends’ in Europe were perfectly OK, and members had no qualms importing their bespoke suits from London.

Unknown to them, or so they claimed, the Paris-based group that sponsored their debates and soirées was a front for the CIA, and some of their guests and lecturers were spies from both sides of the Cold War. It was my father who told me this, how his own father had written letters and articles to try to salvage the Club’s reputation.

One time, walking down the Club’s hallway with my father, he stopped and lifted me up to see a group photograph on the wall. He pointed out a man he described as ‘a famous English novelist’ who ‘came through our city in the seventies’, taught creative writing at the university, and gave talks at the Club. The novelist had turned out to be an agent working on a joint US–UK mission. I was twelve or so at the time when he shared this with me. That photograph, with the rest, including portraits of my father and grandfather, is still up there.

‘Someday yours will be on that wall,’ Belema, my agent slash manager, said to me when he delivered the news that I’d be giving the Club’s New Voices Lecture.

He’d done the legwork as usual, and had prepped me in advance, warning me to shelve my grudge against the Club. Whether I liked it or not, he said, I was now – and always had been – a part of ‘the establishment’. And he intended to ‘milk the hell out of it’ for our ‘mutual benefit’, especially now that I had acquired an ‘American dimension’.

The first thing he did when I returned from the US was to offer me a two-book deal to write about my experience. He had sold ten acres of prime family land outside the city to pay me a small advance. He bought ad spaces in national newspapers to announce the deal, and he made donations to institutes and think tanks across the country in preparation for my future book tour. ‘I’m thinking ahead,’ he said. ‘When I knock on their doors next year they’ll open.’ The plan ‘is to make you big here’, and then ‘sell rights’ to major publishers in the US and the UK. ‘Big money,’ he said, and I admired him for his strategic thinking. I admired him the way I never did before my journey to the US. And it was this admiration that fuelled the speed at which I began work on my two-volume memoir of life as experienced in the United States of America:

Running Loose in a China Shop, or Surviving America One Misadventure at a Time

and

Seductions of the ‘New Rome’ or the Journeys of a Barbarian in the Imperial Centre.

My lecture at the Club was ‘drawn’ from the two works in progress, a fact that was as far-fetched as some of the ‘encounters’ in the memoir.

As I later gathered from my agent, the lecture itself, which I delivered with so much confidence that I almost believed every word, was funded by the Marshal Foundation for the Humanities, an American organisation with headquarters in Washington DC, a revelation that made me chuckle in delight as I squeezed lemons onto my plate of shrimp and eyed the line of expensive wines and champagnes in the corner of the lecture hall.

After finishing the shrimp, and with a glass of wine in hand, I stood by the wide glass wall, looking at the city as it lay below, sloping towards the Atlantic Ocean, curling and relaxing as the mid-evening sun warmed it.

I was in this contemplative mood when a hand rested on my shoulder. ‘Beautiful, isn’t it?’ It was Dr Mohammed M. Bukoram, once described as ‘the best post-colonial social theorist of the black Atlantic’. He said something about the city as a ‘multi-layered temporal space where times converge, where one form of epistemology is superimposed on the other’.

I had a faint understanding of what he was talking about, or thought I did, how the Middle Ages could still be glimpsed in broad daylight, in the lives of children shitting outside their makeshift shacks, as the twenty-first century cruised by in the latest SUVs, or looked on from the twenty-first floor of the New Tower.

I replied in the language of critical thought that I had picked up in the US. ‘I know,’ I said, ‘it’s a classic post-colonial picture of co-existing temporalities… the past understood in discursive proximity to the present… quite impressive, and symbolic of diversity as both socio-economic and spatial.’

I caught a glimpse of suspicion in his eyes. I excused myself and fled.

I signalled to my agent that it was time to go. He moved me around the room saying his big thank yous to the big men and in a few minutes we were out of the door.

In the elevator going down, he pulled out a bottle of champagne from his leather bag and handed it to me. He had done what I’d asked him to do.

I hid the bottle under my suit and undid my silk bow tie as we exited the building.

We walked towards the car park, where his beat-up Peugeot 504, passed down by his grandmother, waited as our escape vehicle.

The twenty-minute drive to my place lasted three hours.

Sitting in traffic, the windows rolled down, we knocked back the champagne and started out on a bottle of vodka he had in his car.

Halfway through the vodka I had the urge to reproduce some of my ideas for future talks to the passengers in a blue-and-white Volkswagen bus pressed very close to our car.

The noise around us, coming from the cars and lorries and hawkers and shops, meant that I’d have to scream to be heard. The image of my drunk self shouting into the open air repulsed me. I tried instead to steady my gaze, and studied the faces on the bus as headlights pierced the growing darkness around us. I could almost feel the heat they were enduring, crammed into that bus without air conditioning, trapped in traffic, sweating together, waiting as they’d been conditioned to do.

On the other side, my agent was making kissy faces to a woman in a white Range Rover. She ignored him, her windows rolled up.

A hawker carrying ripe bananas and apples appeared between our car and the bus, singing the praise of his goods. A mere child, fourteen at most.

He leaned in and asked if I wanted bananas or apples. I could smell the bananas and the apples mixed with the dense odour of fumes and general rubbish from everywhere.

I said to the little boy, ‘Apples are not grown in this country, you know.’

I felt an inexplicable urge to say something different to him, to invest in him the way I could, to shift his mind away from our immediate surroundings, to help him imagine another world. I was experiencing a combination of compassion and loathing, a sense of powerlessness so strong it made me nauseous. I waved him off and reached for the vodka.

By the time the traffic eased I’d passed out.

I woke up the next morning in my room, on my beloved narrow bed, squeezed between my agent and a large woman who looked twice my age. We were all naked. Her enormous legs on top of me, my right leg on my agent’s. I sighted the trace of coke on a corner of my desk, next to the takeaway bag from the Silk Road, the new Chinese restaurant a few blocks away.

I wrestled myself out of bed, tiptoed to the window and cracked it open to let in fresh air. The sun was blinding. The chorus of small generators came from all directions, as always, so normal it would be odd not to hear them.

I turned around and saw that Belema had flipped to spoon the woman. I vaguely recalled him making a phone call at midnight, saying something about ‘a better package this time’.

The image of the three of us crowded into my narrow bed, tumbling like disposable gladiators in an ancient arena, amused me. It also brought back memories of my first threesome in the United States, an experience that was worth more than the seminars and workshops offered as part of my fellowship at William Blake College in Boston.

Thinking back to the US, and looking at my agent spooning the ‘better package’ on my bed, I thought of the single phone call that had transformed my life, that made it possible for me to contemplate threesomes as a practice, an act of private resistance in a society dominated by heteronorms and outdated sexual protocols.

I re-crossed the room towards the kitchen, to make myself a pot of coffee.

I paused briefly at the wide G-string and pink bra by the door, next to my laptop.

I looked at the stranger’s possessions as if they held a special clue to some puzzle.

I picked up my laptop and entered the kitchen.

The coffee made, I sat down at the new plastic table I bought the week I returned from the US, the same week I installed my high-speed wi-fi and bought a small Yamaha generator. It was all thanks to the miracle of the dollar. I had not had many coming back, but the exchange rate meant that I could afford some of the basic necessities of a modern society. I also installed iron bars on the main entrance downstairs, to keep petty thieves and kidnappers away, and I invested in a new French press and a fancy electric pot.

I poured myself a cup of coffee and began to go through my emails. Nothing important.

I went to Twitter. Three DMs, including one from the North Rainbow Alliance (NRA), a group my agent had partnered me with to run Zoom workshops on anti-racism ‘for those who could not be bothered’.

I was still in the US when he sold me to the Montana-based group as an ‘understanding expert on all matters black and ethnic’. He had played up my background as a ‘son of the black Atlantic, whose maternal ancestors were descendants of slaves who came back to West Africa’. If Americans were going to devour themselves, he said to me afterwards, someone might as well hide under the table for the crumbs.

My first Zoom workshop for the NRA was delivered from a motel in Nebraska. Following my agent’s instruction, I had gone to a local store and ordered an American flag and used it as a backdrop. My audience that day was a father and his two sons, third and fourth generation farmers who’d lived in the same town all their lives, full members of the NRA. Their issue: a tweet from the farm’s handle that went viral, a nasty remark about migrant labour.

The boys were in their thirties, their faces concealed in the sort of facial hair Marx would have admired.

Following their example, and to make them feel more comfortable, I reached for the large beer can standing behind my laptop. And we had a delightful time noting all the things we had in common: the love and defence of liberty, and how the world’s problems would be halved if more people drank. There would be zero terrorists, I said, if Muslims had a beer a day. I cited study after study in ‘journals’ and referenced historical events that never happened. I sensed they knew I was bullshitting them; maybe they didn’t, but no one complained. The NRA wired payment to my agent’s PayPal, and signed up more members for my workshop.

The following week I zoomed with a woman in Florida who was fired from her job for pointing a gun at a black couple who had just moved in to the RV next to hers. She wept throughout the workshop, speaking her ‘truth’ of the matter, and I ‘co-wept’ with her, assuring her that the ‘universe’ would always absolve those whose actions came from ‘a place of good intention’.

My agent had looked her up in advance. I knew she’d visited India and had lived for many years in Albuquerque, where she ran a Native gift shop before moving to Florida.

For her I memorised lines from the Bhagavad Gita, and threw in made-up African proverbs to reassure her that ‘authentic’ Africans like myself would agree that she was innocent. She left me a five-star review and sent me a personal tip ‘for just being human’.

The NRA was a generous client, so the DM from them reduced my hangover by a half. Their social media handler and I had become e-friends of sorts, DMing jokes about the prevailing cancel and call-out culture and how it stifled meaningful conversation. I couldn’t care less about these subjects and she, in her early twenties, ‘born and raised in Montana’, did not particularly sound like she understood the history and complexity of the problems. But she advanced with enough confidence to sound convincing. I went along and grew to admire her steadfastness.

‘Could you do a short piece on the situation in Nigeria?’ she asked. ‘See #StopKillingUsLikeRats and let me know.’ She included links to videos and Twitter handles and I followed the links.

While I’d been at the Coastal Humanities Club, quoting Thoreau to that learned society, enjoying their shrimp and fleeing with their champagne, my city was ablaze with protesters marching against a special branch of the National Police Force, a branch that was notorious for extra-judicial killings, kidnappings and unexplained arrests.

The pictures I saw online made my stomach turn.

She wanted to know if I could compare what was happening with the Black Lives Matter movement in the US; maybe the police brutality in the US wasn’t just a racial thing?

I’d written a piece along those lines a month or so after my return from the US, a short piece that made general statements comparing racial violence in the US with ethnic and political oppression in Africa, urging my readers to ‘de-emphasise race and amplify the human condition as expressed the world over’. The idea was hers and the piece was sold to The New Frontier, a politically ambiguous online newspaper.

This time around I couldn’t bring myself to contrive a response to her DM. I was shaken by the images of young people in my city making world headlines as they stood up for themselves, pushing back against a society that was designed to dehumanise them.

I closed my laptop, left my coffee and returned to my room.

My agent and the woman whose identity I still didn’t know were still asleep, their bodies entangled as though they shared a spine.

I lit a cigarette, went back to the window, and listened to my city as it came floating by in its familiar noise. I closed my eyes and for some reason, perhaps the bite of conscience, I began to think of my ‘trial’ at William Blake College, the day I was officially expelled from the programme for emerging writers.

2

I saw the dean’s office again, and pictured the oak tree outside his window. I could hear his voice and how hard he was trying to stay calm as he tiptoed around the subject. ‘We expect two things from our fellows,’ he had said that day, trying not to raise his voice, ‘to produce work in the genre for which they were accepted, and to attend seminars they are leading or participating in. Your colleagues have all produced work and have actively engaged our students, but you, Frank, have hardly been a part of this programme at all.’

I felt again the intensity of his pain, how he paused to collect himself, relaxing the deep line that had appeared on his brow, adding a layer of sadness to a face already battered by the excruciating demands of academia.

When he continued, he expressed his ‘surprise’ (meaning disappointment), that I ‘came all the way here from Nigeria and could not so much as produce a short story in four months’.

At this point I tried to say something but his frustration got the best of him, turning the rather civilised dean into a little savage.

Raising his voice to counter mine, he continued: ‘I recall sending you an email to see what we could do. I mean, how we could help you adjust and deal with whatever you were going through. Your response was, and I quote, “I am on to something.” That was in April, Frank, three months after you arrived. It’s May now and… I don’t know, Frank, my hands are tied here.’

He raised both hands in surrender, brought them down and pushed aside a stack of files, making room for his expansive palms to rest on the ancient mahogany desk he must have inherited from Horace Broughton, the first dean of humanities, whose daguerreotype by Albert Southworth was among those displayed in a case in the lobby.

A giant portrait of William Blake himself, not the English poet, was hanging behind the dean, regarding me that day with a touch of disgust and disappointment. And I swear I heard the seventeenth-century merchant, whose other ventures in the area of human cargo are well documented, mumbling under his breath, ‘I did not start this college to offer free rides to ne’er-do-wells from Africa.’

The other committee members were silent for the most part. But I knew they’d all reached a decision: to send me packing for ‘non-performance’ and ‘non-participation’.

Dr Kathryn B. Reinhardt, director of ethnic studies, was especially cold for reasons I understood only too well. She wondered if I had any idea how my ‘behaviour’ impacted what people thought of Africans. I said I wasn’t in America to represent anyone but myself. ‘Besides,’ I added, ‘you have Barongo Akello Kabumba. He does a good job of representing his dear Africa.’

Sharon ‘Perky’ Hollister was present in her capacity as the academic coordinator responsible for the William Blake Program for Emerging Writers. She managed to speak, offering me a second chance that we both knew was useless.

‘Well, Frank,’ she said, ‘you’ve got some time to share work, and we could arrange one or two projects with students over the next few week.’

‘What if I don’t produce any work or know that I may not be able to deliver?’

It was a thoughtless question. Childish, maybe. But I was already considered a disappointment and I wanted to leave with a bang. I had made a point of showing up late for the ‘meeting’, swaggering in after two pints at The Snug on Coolidge Street.

At one point during the ‘trial’ I wanted to interrupt the dean and make him see the bright side of things. Well, I thought of saying, you now know things like this are possible, which gives you something to plan ahead with, you know, a contingency plan for unproductive Blake Fellows. Another part of me wanted to make it clear that I intended to write but found myself in a new world where fiction no longer existed, where everything was so drummed up that my senses began to turn against themselves.

I had applied on the strength of the slim novel I wrote and published at twenty-four, The Day They Came for Dan, a coming-of-age story set in a fictional version of Port Jumbo, my hometown on the southern coast of Nigeria.

The novel was poorly edited and proofread, lacking in punctuation and peppered with embarrassing typos (‘she’ repeatedly spelled as ‘shay’) – none of which was a deliberate experiment in style. It sold only fifty copies and was already out of print, or ‘rare’, as Belema, who published it, would say.

And it all began when a copy, possibly flung out of a window by a dissatisfied reader, fell into the hands of one Mrs Kirkpatrick, who was visiting her daughter in Port Jumbo.

She’d gone with her daughter to see the weekly street market at Pipeline Bypass, near the intersection which ran east to a cluster of abandoned Slot Oil & Gas equipment stores, and was enthralled by the way books were displayed on mats, how the booksellers called you to come see the titles. I can still hear the ring of her voice when she phoned to share with me her encounter with my book, speaking as though we’d known each other for years.

I was flattered by that call from a white stranger and fan in Nigeria but also irritated by her intrusion. Her opening remark was startling. ‘Hello, is this Frank Jasper, the writer?’

I said yes with a start, more in response to her accent than the question. I should have said no, or at least corrected her: ‘This is Frank Jasper, the recovering writer. You should have called five years ago, when I thought I was a writer, or was suffering from an illness that made me see myself as a writer.’

It was a midweek afternoon. I was still in bed. Her call was a wake-up alarm I didn’t need.

‘Your book stood out from everything on display,’ she said after her anecdote about street booksellers in Port Jumbo. ‘I bought it and was glad I did. By the way, is that a Yinka Shonibare on the cover?’

‘Yes,’ I answered, calibrating my brain to match the pace and tone of the conversation. I waited to find out where her call was leading.

‘I knew it,’ she gushed. ‘I guessed it from that colourful Dutch wax.’

What you don’t know, I wanted to say, is that my publisher pinched that image off the internet, without consulting the artist or his representatives. The whole book was a complete joke. And just as I was about to inch towards thanking her and hanging up, she fired on. ‘It’s such a good book, Frank – may I call you Frank? Such a good book. I can almost touch your characters, and boy, how did you get away with handling such a delicate subject, I mean, an openly gay character in a novel set in 1990s Nigeria?’

Well, I thought of replying, there were only fifty copies printed and sold, ninety per cent of which went to my publisher’s close friends. That took care of the risks involved in ‘handling such a delicate subject’.

I held on to my thoughts and thanked her for reading my work, and for her kind remarks.

I wondered how she read the whole thing without cringing at the errors and the poor print quality. These Americans are something, I thought. They fall for anything and anyone, or pretend to. They flatter you until you begin to see sparks of genius where none exist.

Her enthusiasm that day made me want to reread the surviving copy of my novel that was languishing under the bed, a move that I knew would make me revisit my early twenties, the crisis of culture that marked it, the ridiculous outpouring of Byron, Pushkin, Huysmans, Proust… onto the pages of a tiny novel set in modern Nigeria. The big ideas about the world that I shoved down the throats of my few readers.

I believed then, and still do, that rereading The Day They Came for Dan would have plunged me into unthinkable despair, the kind I experienced when I read a copy of the first (and last) print run and spotted the typos. For ten days I barely ate anything. On the eleventh day, I exploded into a rage that I thought I was incapable of. I tore up the book and threw the tatters out of the window. Two months later, regaining a measure of confidence in myself and my work, I ventured to mentally revisit the cursed book; I wrote a review and sent it to The Ganges Review of Books under a false name.

In the review, I compared my novel to everything Amit Chaudhuri had written, tracing my influences, pointing out the themes, noting my references to obscure writers and artists, concluding with a taut bombast: ‘Readers of Proust will find in Jasper’s work the same keen eye for the subtle shades of the human condition.’

The Ganges Review of Books, managed by some chap with an astonishingly long name, responded enthusiastically: ‘Dear J.C. Barnes… most delighted to run this review…’ And they did, and I visited the website every day while lying in bed and peering into my phone and enjoying the way my alter ego had captured the very essence of The Day They Came for Dan.

Two weeks or so later, The Ganges Review of Books disappeared from the internet. ‘Cannot find host’ read the page when I tried to load the website. I refreshed it and was redirected to a website selling Viagra.

That was the final blow. It was clear that my book would not go far, that my hope of gaining attention in the West by way of India was a dead end. Then Mrs Kirkpatrick showed up. ‘It would be great to meet you, Frank,’ she continued. ‘My daughter Iris and I would really like to host you sometime. How about this weekend? It would be nice to meet you in person.’

It was happening too fast. I felt my head pounding, my heartbeat racing. I didn’t know how or what to answer. I forced myself to say something. ‘Give me a second to check my calendar.’ There wasn’t any calendar to check. What I wanted was a moment to take a deep breath and relax. I had no appointments to cancel. No place to go. I liked not having things scheduled. The thought of agreeing to meet someone at a fixed time was a major source of distress to me. But there was something about her, something in her happy voice, that already made me feel an answer in the negative would ruin her day, perhaps ruin her entire visit to Africa.

I picked up a book and held it close to the phone, ‘flipping’ through my ‘schedule’. Finding no conflicting appointment, I agreed to meet, a decision that was rewarded by a ‘thank you’ so loud I had to hold the phone away from my ear.

When the call ended, I sat on the edge of my narrow bed for a few minutes, trying to feel something. Belema, my publisher, had sent me a text: ‘Hey Frank, long time, no hear. Got a call from one Mrs Kirkpatrick, Betty Kirkpatrick, I think she’s American, she liked your work and asked for your info. I gave her your number. Expect a call from her. Hope you’re OK?’

I didn’t bother replying. My shoulders ached and I felt nauseous. I knew precisely why this was happening; too much activity, too much external interference. I wasn’t used to this kind of attention.

I went to the bathroom and sat on the toilet seat and stared blankly at the open door, trying to silence Betty’s voice, which kept ringing in my ear.

3

A week later I found myself in a posh part of Port Jumbo, a far cry from the shithole where I lived, where the houses were crammed up against one another, sharing space with open sewers and vast piles of garbage. The streets were tidy in this other side of the city. You could pick up your doughnut if it fell to the ground and be greeted by carefully watered flowers and tender bushes on your way up. The air was fresh, as if filtered by God himself.

I was looking for 10 King Edward Close, named after Karibo ‘Edward’ Amakiri, a leader of the Kalabari people in the colonial era.

The house wasn’t hard to find. A milk-white building rising above an imposing fence with barbed wire spiralling from end to end.

I knocked twice on the gate and someone opened the peephole, stared for what seemed a lifetime, then unlocked the gate for me. His bloodshot eyes, projecting from an impassive face, sized me up and down, and then he screamed as though I was a whole mile away: ‘Ahh yuuu the raitah?’

‘I am,’ I answered as quickly as possible.

He let me in and spat out something he was chewing. It made a nasty sound as it hit the cobblestone. I flinched. He frowned and pointed me to the door.

A mere two steps away from him a blue door opened ahead of me, revealing an older woman with a kind look on her face, a turquoise bead necklace with a periwinkle-shaped pendant around her neck, and a pair of round glasses behind which a set of eyes glinted their welcome. She’d seen me at the gate and knew I was the writer. The writer. Frank Jasper, the writer! The whole thing was beginning to sound sweet and enticing. It had, at least, landed me in that posh place, and who knew what else would happen?

Inside, the white walls were covered with locally sourced art – hanging sculptures made from scrap metal, paintings of waterside shanties with the ocean in view, a black mask that was as generically African as it was hideous. A black grand piano stood to one side, near a staircase that curled up into a circular gallery. A blown-glass chandelier with rainbow-coloured petals drooped. I could see my shadow on the hardwood floor, as sunlight poured in through one of two broad windows.

Looking out, I saw a garden at the back, flowers in bloom, and four chairs tucked under a picnic table. I saw my book on the couch, a green page marker sticking out, and I felt a knot in my stomach.

‘It’s so nice to finally meet you,’ Betty said, shaking my hand reverentially with a slight bow. ‘Please make yourself comfortable.’

I had imagined what she would look like, this generous reader whose unexpected attention was gradually reviving a sense of what I was, or thought I was: a writer. I had imagined her with short hair, greying, and a few matronly lines under the eyes. But in front of me that day, against my presumptions, was a towering figure with flowing brown hair, slender, with visible signs of hundreds of hours spent at the gym or running the streets of wherever she lived in America, so much younger that at first I thought she was the daughter and not the woman who would become my gateway to William Blake.

She started saying something about her daughter’s house, introducing herself properly, asking if I needed anything, tea or coffee. I was too distracted to pay attention, and I nervously answered ‘both’ to her offer of tea or coffee. ‘Sorry, tea is fine,’ I corrected myself.

As she went to make me tea, I tried to replay her introduction, most of which I hadn’t caught. She was born and raised in Charlestown in Massachusetts, to an Irish family whose ancestors fled some nightmarish event in the old country. Her father was a schoolteacher, or was it a college professor? Her mother was a civil servant who worked for some government agency in Boston. And a few things were said about how rough the neighbourhood was when she was growing up there, how my book had a similar ring and atmosphere, with its range of bleak characters whose lives were constantly marked by violence, the clear line of socio-economic divide between households in close proximity. And then she went off to college to study anthropology, did the Peace Corps in Tanzania (or was it Namibia?), and had since felt a strong connection to Africa; her daughter no doubt took after her. She herself wanted to be a writer, and had in fact started a novel many years ago – a young adult novel inspired by her experience teaching kids in Namibia (it might have been Tanzania) but, you know, life happened, and the novel-in-progress was shelved.

When she brought tea, she also brought a thick photo album she’d put together and often carried with her on trips to Nigeria (clearly for the benefit of her local acquaintances).

The album contained photos of Charlestown past and present, and other places in the Boston area. The Bunker Hill Monument was the first to catch my attention, the way it stood against the cloudless sky, intimidating.

She carried on talking as I flipped through the pages, struggling to conceal my growing disinterest. She provided the commentary, complete with back stories for each photograph.

There was a badly shot picture of a church, which she promptly told me was the well-known Old South Church. Next page, a picture of Blake Hall, the main auditorium at William Blake College. It was here that she brought up the fellowship at William Blake.

‘Actually,’ she said, ‘my husband is a professor at William Blake.’

‘Oh,’ I said, without looking up from the page.

‘You know,’ she went on, raising her face in a way that suggested that I take a break from the album, ‘you know, there’s this great opportunity for young writers at William Blake.’

‘Oh,’ I said again. I looked up and attempted eye contact but found myself gazing at the window to her right.

I could see how close we were on the couch, and I tried to imagine what else was crossing her mind, whether anything was expected of me in exchange for this opportunity. She was, after all, from a country that popularised the saying, ‘There’s no such thing as a free lunch’.

‘It’s an extraordinary programme,’ she carried on. ‘They started it a few years ago, and they’ve had writers from India, Scotland, Germany, New Zealand. There was a writer from South Africa, I don’t remember her name, I think she was South African, I mean, she wasn’t African African.’ She unleashed a confident smile to underscore her own observation.

I reached for my tea.

The cup was lukewarm.

I took a casual sip and returned it to its place.

‘Interesting,’ I said.

‘And the programme is fully funded.’

‘Wow.’

‘I know.’

‘Generous,’ I added.

‘You know, I bet they’d be interested in your work. I know they’d be happy to have a writer from Africa. You should look it up and tell me what you think. I’m more than happy to put in a word for you.’

I didn’t know if she expected me to leap and dance at the opportunity, and I couldn’t tell if my not leaping and dancing disappointed her. What I felt was a weight rising and sinking in my stomach. My palms began to sweat, and the photo album on my lap began to feel like a pot of hot coal.

‘Just think about it,’ she said, and I replied, a little too loudly, ‘I’ll think about it,’ to which she replied, ‘Great,’ an octave above my response.

I was about to say something else but she was already onto a new subject. ‘So, Frank, tell me about yourself. Do you have family here?’

A dreaded question. How and where to begin? Tell her that I worked two days a week at the post office and two nights a week as a bookkeeper for a seedy brothel somewhere in town? My impulse was to awkwardly recite my Wikipedia entry: ‘Frank Jasper is a Nigerian poet and novelist, the author of The Day They Came for Dan (Cocoyam Editions, 2008). He holds a first degree in English and History from the University of Port Jumbo, and a Master’s in Interdisciplinary Studies from the same university.’