Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: BuilderMaker

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

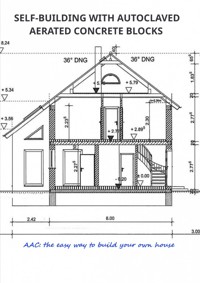

Large format, print editons of this book, with full colour photos ilustrating the text descriptions, can be purchased at www.mybestseller.co.uk/M.Keating This is the story of our house build in Germany. This book is intended as a birds-eye view of the work, not a guide to absolutely everything involved with the process. I wrote it is to inform you, the prospective self-builder, on the work involved, in order to help you decide whether this is something you feel you could do yourself. It will not be physically possible to do absolutely everything by yourself, you will still occasionally need a helper or two and the building process may vary slightly in other countries due to availability of specific materials, but the basic procedures in the book remain valid. When we signed the contract for our building materials we were given a German book on self-building with AAC. I didn't speak German and could not find an appropriate English language book, so I decided to photo-document our entire construction process and write a book on it. Many of these photos are included in this book to aid to full comprehsion of the house build (there are no photos in the e-book).

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 91

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

SELF-BUILDING WITH AAC

The Background to this book

Misconceptions about AAC

Choosing what type of house to build

Prefab kit-house

Log house

AAC Block House

What exactly is an Autoclaved Aerated Concrete (AAC)?

Kalksandstein

Load bearing, PP2 and PP4 explained

Baugrundstück (Building Plot)

Architect

Plans

Recycling

Windows

Frost protection barrier

Surveyor

Builders toilet

Electricity supply

Water supply

Concrete Pad (Bodenplatte)

Waste pipes and utilities

Pumping concrete

Plastic damp-proof barrier

Steel

Binding rebar steel

Electrical earth

The second layer of rebar

Shuttering

Buying concrete

Laying the first blocks

Wall construction methods

Damp proof course

Band saw

Door lintels

Window Openings

Roller Shutters (Rolladen)

Ceilings & floors

Ringanker

Stairs for construction (Bautreppe)

Scaffolding winch

AAC ‘U’ blocks

Upper-level walls

Interior wall shuttering

Cold bridges

Steel support struts (extra support for roof)

Roof work

Roof Beams

Chimney access window and roof step

Roof cross-bracing

Under-roof trim, ‘cladding’

Roofing felt

Roofing battens (Lattens)

Fascia and soffit

Guttering

Roof Tiles

Windows and doors

Chimney

Chimney service doors

Chimney construction

Capping the chimney

Bitumen damp-proofing

Planning electrical wiring

Fusebox, electrical wiring, sockets and switches

Priming and plastering (internal walls)

Bathroom and utility room

Plumbing and heating

Under-floor heating

Screed (Estrich)

Bathroom ventilation

Stairs

Exterior windowsills

Insulation for concrete baseplate and exterior walls

Exterior plastering

Plasterboard ceiling construction

Plastering ceiling gaps

Switch and socket trim

Installing a wood burner

Flooring

Carpet

Wall tiles

Balcony railings

Further Information

The History of Autoclaved Aerated Concrete (2014), W. van Boggelen

Factory installation manual for plan-element AAC

Electrical and wiring differences between the U.K. and Germany

RCD Residual-current device

The Background to this book

This book outlines the basic steps and methodology on self-building with Autoclaved Aerated Concrete (AAC) blocks. It is based on the construction of our own house in Germany. This is the story of our build.

Upon moving to Germany, we sold our house in Britain and used the funds to build a new house. When we signed the contract for the building materials, we were given a book on self-building with AAC. My German was terrible and I was unable to read it. I was also unable to find an English language guide to the AAC building process, so I decided to write one myself as I built my house. The sequence of the book mirrors the sequence of the build. Hopefully, this book will serve to de-mystify the building process and further encourage self-building with AAC, a brilliantly simple and effective construction material.

This guide outlines the building process, methodology, and pitfalls to avoid. Since it is based on our build in Germany, it may differ from the building process in other countries, not least due to availability of materials. Nevertheless, the basic building process remains the same, although modifications may be necessary. The book is intended as a birds-eye view of the work. It is not a guide to absolutely everything involved with building; rather, it‘s purpose is to inform prospective builders about the work involved, to help decide whether this is something you could do by yourself, or not. If you do decide to self-build, the use of occasional paid labour, or friends, will occasionally be necessary due to such pure practicalities as weight, dimensions and the best practice of concreting a complete section before any gaps start to set. One example of this would be no access to a concrete pump and thus having to use buckets to fill shuttering on top of a wall.

Misconceptions about AAC

In the process of researching this book, I discovered widespread misconceptions in the British and Irish building trade. Many workers believe that AAC cannot be used in rainy countries because it soaks up water too easily. This is not true.

I believe these misconceptions arises from the fact that most British and Irish workers are unfamiliar with AAC, since it not sold in builders markets or DIY stores. It is possible to buy lightweight, aerated concrete blocks –but these are NOT AAC. These lightweight blocks easily soak up water and, unlike AAC, become much weaker when wet. I suspect people may have confused these blocks with AAC. I also suspect that there are vested interests in the construction industry, who are satisfied with the status-quo and have no desire to change anything. Perhaps green building practices have a lower profit margin?

AAC is a green, lightweight, fire-proof, energy-saving building material that has been in use for over seventy years. It is manufactured from natural materials: water, sand, lime, cement and a small amount of aluminium powder. When the ingredients are mixed, gas is produced from the reaction between the lime, aluminium and water. The gas produced is hydrogen. This gas expands and creates many tiny bubbles, causing a doubling is size of the material, in the same way that carbon dioxide causes bread dough to rise.

The still soft, expanded mixture is moulded, sliced, and then heated under high pressure steam (autoclaved) for 12 hours. The temperature required for autoclaving is far less than that required to fire traditional bricks. The autoclaving process creates a solid material which is AAC. The hydrogen gas dissipates during the process (hydrogen is the smallest element and escapes easily), leaving precisely formed AAC blocks, or plan elements.

The pores in the AAC are sealed, they do not interconnect. The upper and lower surfaces of the blocks are completely smooth. Water does not soak into the blocks easily and construction can continue in rain. Pores in AAC are well closed, only surfaces will be wet during rain and water will not penetrate deeply. During factory testing, samples had to be submerged for 3 days before they absorbed 70% water (reference, Aircrete.com).

Provided mortar is applied correctly, it is perfectly possible to build with AAC in inclement weather. AAC blocks are supplied to the customer on pallets, sealed in heat shrink plastic, and can be left in the rain indefinitely.

Self-building: a comparison between the U.K. and Germany

We built our house in the former DDR (East Germany), where it is relatively easy to acquire a building plot. The German housing industry runs the gamut from family run, to SME, to large corporations. Conversely, the UK is dominated by mega-companies which purchase large tracts of land and build as many houses as they can, at minimum cost and maximum profit, with seemingly little concern for aesthetics or modern, green construction methods and materials. They commonly land-bank property, preventing anyone from building on it and creating an artificial shortage of land zoned for residential housing.

In theory it should be possible to purchase a building plot when one becomes available. In practice however, building land is in very short supply in Britain and when previously unavailable land is re-zoned to allow construction of domestic dwellings, it is usually done in relatively large amounts which are quickly snapped up by major developers; small builders do not stand a chance. The large builders, in-effect, shut out people wishing to buy a single plot and build their own house. Individual plots which do end-up on the market, command a premium.

Britain is blighted with bleak and un-remarkable housing developments. If one wishes to modify one’s house, one must fight tooth and nail against local planners, concerned with maintaining the (often bland) look and character of an estate. It would make far more sense to encourage housing diversity. One would be hard pressed to find two identical houses adjacent to each other in suburban Germany. I strongly believe that diverse housing styles add to, rather than detract from, the aesthetics of a neighbourhood.

In Britain, we lived on a street of identical 1950s, ex-council houses. The houses were equally dreary, Tyrolean sprayed (imitation pebble dash), some with imitation stone facades. A planning officer denied a neighbour permission to build a dormer because a small corner would be visible from the street. He said he was concerned that the character of the estate would be damaged. Any change in its dreary character would have been an improvement.

German planning laws are generally less restrictive. It is not as difficult to find a building plot (Baugrundstuck). Houses are frequently built by small companies and individuals and, although large construction companies do exist, they do not have a stranglehold on the market. As in the UK, the large German building companies do build estates of similar looking houses, however, there are many locations where every house on the street is different. That is not to say that there is no repetition of house styles.

Many small companies only have a selection of four or five different house styles to choose from. However, the choice of finish is unlimited. Consequently, you might see a house with a sharply peaked roof and Georgian windows, clad in weathered brick (AAC building are frequently clad in brick) and a few houses away, the same style house with plain windows, plastered and painted a cheerful yellow. They look like entirely different houses.

Choosing what type of house to build

Prefab kit-house

We initially thought it might be better to buy a kit-house (Fertighaus). Not because they are any cheaper than traditional brick or block houses (they’re not), but because we assumed that it could be built in a few days so we could move in quickly and save money on rent. We visited a demonstration house and, after speaking to a salesperson, discovered that they have to first plan the house with you, then build it at their factory, which takes between six months and a year, then drive it all on the back of a couple of lorries to your building plot, and then put it together for you. This last part is what takes 3 days. The quick, pre-fab house build you see on TV does not reflect reality.

Whilst the show house looked nice, the exterior walls were pre-formed concrete slabs, bolted together, insulated externally with Styrofoam, and finished in epoxy render. The interior walls were plasterboard, with minimal insulation against sound or temperature. We quickly decided that we did not like the way it was built, and we did not want to wait a year for it.

Log house

Log-house kits are delivered as a stack of pre-cut and slotted logs and, with help, the basic structure can be built in about a week. They are easy to build and fit together like Jenga. Our neighbours built one. They said that the house creaks as the wood settles and spiders love all the nooks and crannies. The spiders were the deciding factor for my wife so a log house was off the agenda. In 2020, the price of wood doubled.