6,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

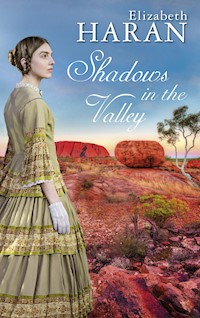

- Herausgeber: Bastei Entertainment

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

South Australia, 1866. Beautiful but destitute Abigail is forced to marry an old landowner who desperately needs heirs. But on their wedding night something terrible happens ...

Abbey flees Martindale Hall. She has no memory of the previous night, but no one believes her. With no one to trust, she seeks refuge in the neighbouring town of Clare. There, her luck seems to change. She meets Jack Hawker, who is looking for someone to tend to his mother on the remote farm Bungaree Station. Jack hires Abbey for the job. But Abbey's respite is short-lived. Days later, a visitor from Martindale Hall turns up on the farm, accusing Abbey of a horrible crime ... Will Jack believe her? Or is she doomed to a life of penance?

With an eye for detail, Elizabeth Haran is the author of numerous other romantic adventures including Island of Whispering Winds, Under a Flaming Sky, Dreams beneath a Red Sun, and River of Fortune, Staircase to the Moon, and Beyond the Red Horizon, all available as eBooks.

For fans of sagas set against a backdrop of beautiful landscapes, like Sarah Lark's, Island of a Thousand Springs or Kate Morton's, The Forgotten Garden.

About the author

Elizabeth Haran was born in Bulawayo, Rhodesia and migrated to Australia as a child. She lives with her family in Adelaide and has written fourteen novels set in Australia. Her heart-warming and carefully crafted books have been published in ten countries and are bestsellers in Germany.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 715

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

CONTENT

ABOUT THE BOOK

South Australia, 1866. Beautiful but destitute Abigail is forced to marry an old landowner who desperately needs heirs. But on their wedding night something terrible happens …

Abbey flees Martindale Hall. She has no memory of the previous night, but no one believes her. With no one to trust, she seeks refuge in the neighbouring town of Clare. There, her luck seems to change. She meets Jack Hawker, who is looking for someone to tend to his mother on the remote farm Bungaree Station. Jack hires Abbey for the job. But Abbey's respite is short-lived. Days later, a visitor from Martindale Hall turns up on the farm, accusing Abbey of the inexcusable … Will Jack believe her? Or is she doomed to a life of penance?

With an eye for detail, Elizabeth Haran is the author of numerous other romantic adventures including Island of Whispering Winds, Under a Flaming Sky, Flight of the Jabiru, and River of Fortune, Staircase to the Moon, and Beyond the Red Horizon, all available as eBooks.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Elizabeth Haran was born in Bulawayo, Rhodesia and migrated to Australia as a child. She lives with her family in Adelaide and has written fourteen novels set in Australia. Her heart-warming and carefully crafted books have been published in ten countries and are bestsellers in Germany.

Readers can connect with Elizabeth Haran on various social media platforms:

Twitter: @elizabethharanFacebook: aussieoutbackauthorWikipedia: wikipedia.org/wiki/Elizabeth_Haran

ELIZABETH HARAN

SHADOWS IN THE VALLEY

»be« by BASTEI ENTERTAINMENT

Digital original edition

»be« by Bastei Entertainment is an imprint of Bastei Lübbe AG

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, businesses, places, events, and incidents are either the products of the author’s imagination or used in a fictitious manner. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, or actual events is purely coincidental. This book is written in British English.

Copyright © 2007 Elizabeth Haran, © 2018 by Bastei Lübbe AG, Schanzenstraße 6-20, 51063 Cologne, Germany

Written by Elizabeth Haran

Edited by Amanda Wright

Project management: Lori Herber

Cover design: Manuela Städele-Monverde

Cover illustration © Richard Jenkins | © shutterstock: totajla | structuresxx | kwest

E-book production: Dörlemann Satz, Lemförde

ISBN 978-3-7325-4615-2

www.be-ebooks.com

Twitter: @be_ebooks_com

DEDICATION

I would like to dedicate this book to the memory of the late Edda Merz. I am truly honoured to know I was her favourite author.

CHAPTER 1

Burra – South AustraliaNovember – 1866

From Blyth Street, the three miles of parched earth that snaked through Burra township looked like any other dried up creek bed, cracking to pieces under severe drought. But upon closer inspection, smoke could be seen drifting from holes in the tops of the banks. The holes served as chimneys for hundreds of “dugouts,” carved into the sides of the creek bed. Nearly two thousand people lived in the dusty dwellings. Brought here to work in the Monster Mine, families had hoped to make their fortunes in Burra, one hundred miles from Adelaide in South Australia’s Gilbert Valley.

The sun was setting on a hot November day. For months the creek—now called Creek Street—had been nothing more than a basin for dust and scraggly weeds. Unfortunately, without the whisper of a breeze, the lingering stench of human waste and garbage was suffocating.

As evening approached, the women in the dugouts began preparing their simple dinners, but in the back of their minds, they held a sense of apprehension that had settled with the dust over Creek Street. Suddenly, an eerie, heart-rending cry of anguish broke the tense silence, and everyone became still for a moment. Then the wailing began.

Two tears slid down Abbey Scottsdale’s sun-kissed cheeks as she got up from the dirt floor of the two-roomed dugout she shared with her father. She stepped outside. Many others nearby had emerged from their dugouts. In the fading light her neighbours resembled a forest of trees in a narrow valleysentinels, silent and still.

They knew what the cries of anguish meant, because they weren’t unexpected. Little Ely Dugan had lost his battle with typhoid. A small and frail four-year-old, he’d had almost no hope of surviving, despite the hundreds of prayers said for him. His mother’s agonised cries wrenched at the hearts of those gathered outside the family dugout.

Abbey was eighteen, and not yet a wife or mother, but she felt for Evelyn Dugan, who had already lost a son the past year. In that time, almost thirty children had died of typhus, smallpox, and typhoid fever on Creek Street. And every time a child died on Creek Street, it reminded Abbey of what she had lost personally. She’d been born in Ireland in 1848. Little more than a year later, her brother Liam had arrived, and then her sister Eileen was born eighteen months later. When Abbey was five, Liam had died from smallpox. A year later, Eileen was dead after a severe bout of whooping cough. And, in 1860, her mother Mary, at only twenty-nine years of age, had died from diphtheria.

Disease was rampant in the unsanitary conditions of the creek. But with nowhere else to go, the miners were forced to live in mud dugouts shored up with timber beams. The cave-like dwellings were cool in the summer, but were damp, muddy, and bitterly cold in the winter when the inhabitants were often driven out by the rising creek water.

Brushing her tears from her cheeks, Abbey went back into her dugout. She tied up her long black hair and went to stir the pot of smoked bacon bone soup she’d made for the evening meal. She didn’t know why she’d been spared typhoid and other diseases, and she also didn’t know why someone as young and innocent as Ely had not.

Abbey was waiting for her father to come home from the Miner’s Arms Hotel. He always went to the pub on Thursday evenings, as it was payday, and he also went there most Saturday afternoons, drinking with his friends, men who had also left Ireland to find work. She resented him for not coming straight home from work on Saturdays, but on Thursdays, it gave her an hour alone with Neal Tavis. She couldn’t see Neal on Saturdays because he spent the day working on a local farm for extra money.

Neal was the young man Abbey had fallen in love with. He was eighteen-years old and worked alongside her father, 180 yards below ground in the copper mine. After work on Thursdays, Neal hurried home to wash before coming to see Abbey, so as to avoid her dad. Finlay Scottsdale could be volatile and unpredictable when drunk, and he had made his opinion about Neal very clear. He didn’t want his daughter to marry someone without prospects, and he considered a miner who lived in a dugout to be unsuitable. He wanted better for Abbey than what he himself had been able to give her. Neal hoped Finlay would change his mind if he could buy a piece of land and prove he was worthy. He saved every penny he could, but it was hard because he was a young man burdened with responsibilities, something Finlay was very aware of. Neal supported his mother, Meg, and two school-age sisters, twins Emily and Amy. They lived nearly a mile down Creek Street from the Scottsdales, on the opposite side.

An hour passed, and then a familiar whistle broke the sombre quiet that had befallen the camp as Finlay approached the dugout, inebriated and unaware of what had happened. Abbey listened intently to her father’s whistling, as it was often an indication of just how much he’d had to drink, and, consequently, the mood he would be in. After two or three pints, Finlay was optimistic about bettering their lives, but it was rare that he stopped at just two or three pints. After four or five pints, he could become melancholy or patriotic. When he’d had even more more to drink, he became pessimistic and morose. Abbey hated to see her father that way, but she’d come to realise there was no changing him. Instead, she tried to accept her father for who he was, but also looked forward to her future with Neal.

Finlay was in a good mood for a change, Abbey noted. He was whistling “Brian Boru’s March.” When he was really drunk, he whistled “The Lamentation of Deirdre.” It had been a favourite of her mother’s before she died. Abbey dreaded hearing it because it meant her father’s depression was soon to follow.

“Abigail, my angel,” Finlay said cheerfully, as he ducked his head to enter the dugout. “What fine feast have you prepared for us this night?”

Abbey barely glanced up from the floor, where she was sitting. “Little Ely just passed away, Father, could you please keep your voice down?” she said.

Finlay looked momentarily emotional. “That’s terrible news,” he muttered. “He was a fine little lad.”

“Yes, he was,” Abbey said sadly, remembering his impish grin and curly red hair. She’d always called him a little leprechaun. It upset her that her memories of her own brother and sister had faded, but she would never forget her mother’s endless tears over their loss.

Abbey sniffed, fighting her own unstable emotions. “Did you not hear Evelyn Dugan’s cries as you went by her dugout?”

“No, I didn’t,” Finlay said. He bent to sit down, stumbled, and fell heavily to the ground. Sitting up, he groaned, and then chuckled as he kicked ashes from the fire.

Abbey had seen him in this state numerous times, so she wasn’t alarmed. She clicked her tongue, a habit her mother had employed whenever she was cross with Finlay. For that, Finlay forgave her, as Abbey often admonished him like a wife, which he found strangely comforting.

“Abbey, we’ve something to celebrate,” Finlay said, smiling delightedly.

“What’s that, Father?” she asked flatly as she ladled soup into a bowl for him and tore off a piece of the bread she’d cooked. Some good news would make for a very welcome change.

“You and I have been invited to dine at Martindale Hall this Saturday evening,” Finlay replied excitedly.

Abbey looked across the fire at her father, a frown marring her pretty features. “Why have we been invited to the Hall?” She was perfectly aware of the mine owner’s contemptuous regard for his workers, so she was puzzled why he would invite her and her father to his home in Mintaro. It was described by those few who had seen it as palatial and ostentatious. She was even more puzzled about why her father would accept such an invitation, as Ebenezer Mason was a man with a reputation for looking down on the lower classes and exploiting them whenever he could.

Finlay didn’t answer immediately as he thought carefully about his next words. “I told you, we’ve been invited to dine,” he said. “And it’ll be on sumptuous fare, I’ll wager, maybe a roast leg of lamb with all the trimmings. That would be a real treat, hey, Abbey?” He licked his lips in anticipation. “I hope Ebenezer Mason has plenty of ale to go with it. I’m not one for fancy wines.”

“I’m confused, Father. I thought you had a low opinion of Mr. Mason,” Abbey said suspiciously. Her father had often grumbled about him because he was known for putting profit ahead of the miners’ safety.

“That I did, Abbey,” Finlay said thoughtfully.

“And now?” Abbey asked, confused.

“I’ve gotten to know the man in the last few weeks, Abbey, and I’m ashamed of how I’ve judged him.”

“I thought you had good reason to dislike him.”

“I thought I did,” Finlay said, sounding tired. He began spooning soup into his mouth noisily.

Abbey winced at the image of him doing that in the elegant dining room of Martindale Hall.

“We have to start thinking about your future, Abbey,” Finlay said abruptly.

“My future? What has that got to do with dining at the Hall?” She flushed when she realised what her father might be up to. He often hinted about prospective husbands, men he thought suitable, like the mayor’s son or the manager of the Royal Exchange Hotel. He’d even tried to set her up with the chief constable, a man in his late thirties. Abbey was terribly embarrassed, as she believed these men were either too old or above her in station. Surely, he wasn’t thinking that Mr. Mason’s son would be interested in her? But then she remembered hearing that his son didn’t live at the Hall. She’d heard rumours that he lived in a cottage somewhere on the vast estate, and that he rarely spoke to his father after a falling-out over his father’s brief marriage to a young woman. But no one really knew the truth behind the estrangement. Friends had pointed out his carriage on the rare occasion it passed through Burra, but he didn’t socialise in the town, so Abbey had never actually seen him.

“Mr. Mason has suggested he’d like to get to know you, Abbey,” Finlay said, noting that Abbey looked displeased with the prospect and a little bewildered. He’d always been frustrated with his daughter’s lack of ambition when it came to choosing a potential husband who could give her a good life, one she deserved.

Finlay was, of course, biased, but he believed any man would be lucky to marry such a beautiful young woman. Not that any man would do. On the contrary. Abbey was a little thin, as her mother had been, but her long, dark hair glistened like coal in the sun, and her eyes were surely as blue as the sea.

“I think Mr. Mason has his eye on you.” He knew it to be true, but wanted to break the idea gently to his naïve daughter.

“What?” Abbey said, now clearly appalled. “Mr. Mason is old. He’s as old as you, isn’t he, Father?” The thought of anything romantic with Ebenezer Mason repulsed her. She couldn’t believe her father would consider someone so old an appropriate suitor.

Old, to someone Abbey’s tender age, was over thirty. Ebenezer was fifty-three, only five years younger than her father, who also hadn’t married young. Finlay had been forty, and Mary had been seventeen when they were wed. In County Sligo, where Finlay’s family hailed from, it wasn’t unusual for men to marry women in their late teens, even though the men were sometimes well into their forties. But that habit was not as common in Australia.

“He’s not as old as me, Abbey,” Finlay said indignantly. “Not quite,” he added softly. He momentarily flinched as a mental picture came to mind, but quickly pushed any qualms he had away. He was determined to concentrate on his daughter’s future security. “You might think him mature, Abbey, but he’s a very wealthy man. That means you could one day be a very wealthy widow.”

“That is a terrible thing to say,” Abbey said crossly. “And I think you are certainly fooling yourself. Mr. Mason wouldn’t be interested in a girl from the dugouts.”

“That’s where you are wrong, Abbey. It is not common knowledge, but he was once a miner, too,” Finlay said.

Abbey’s eyes widened. Like everyone else, she had imagined that Ebenezer Mason had been born with a silver spoon in his mouth in an aristocratic house in England.

“That’s right. He was once penniless until he tried his hand at mining on the Victorian gold fields,” Finlay added, noting her surprise. “That’s how he made his fortune. He struck it rich in Peg Leg Gully in the early 1850s. Three hundred and twenty-four pounds of gold were eventually found there, a nice portion of it by Mr. Mason and his colleagues. Can you imagine that?” Finlay had told his friends in the pub this piece of information. They were astonished, but then the publican whispered that Mason had duped his two partners in the venture. Finlay had chosen to disregard it, certain it was only jealousy rearing its ugly head. “I respect a man who works hard for his money. If he was lucky enough to strike it rich, good for him, I say.”

“How do you know this is true?” Abbey asked. It all sounded a bit questionable as far as she was concerned.

“He told me himself. We’ve had quite a few frank discussions lately.” Finlay stared into the flames of the fire. He’d learned a lot about Mr. Mason over the past two weeks. It would be correct to say that he’d been suspicious at first about why the mine owner had wanted to have a drink with him, and had bluntly expressed his concerns, but Mr. Mason was candid about his motives, and Finlay respected that. It gave him a chance to be just as frank and to tell Mr. Mason that his daughter was a good girl, and unless his intentions were strictly honourable, there would be no association between them. After being assured this was the case, the two men set about getting to know each other, with Mr. Mason hoping they could come to some arrangement.

“Really?” Abbey said, now even more suspicious about Mr. Mason’s sudden affinity towards her father. As for Mason once being a miner, it was hard to imagine him getting his hands dirty, especially when she thought about his snowy white shirts and shiny patent leather shoes. But if her father believed he’d been a miner, then she supposed it had to be true.

“That’s right, Abbey, love,” Finlay said. “There’s a lot of responsibility and worry that comes with owning a mine. I’d never thought about it, but Mr. Mason has opened my eyes, and I now have a new appreciation for his position.”

“It must be a real worry counting all that money,” Abbey said sarcastically.

“Sometimes he’s counting his losses,” Finlay said in all seriousness. “Do you remember last year when four hundred men lost their jobs?”

Abbey certainly did. The morale in town, and especially in the dugouts, had been low.

“Mr. Mason had to cut costs because the mine was deepened, and it cost more to get the copper out, and then copper prices fell. He has to make difficult decisions every day.”

“You’ve often said that he doesn’t care about the workers, only the profits,” Abbey said.

“And I believed that, until recently. I won’t deny it. But I was wrong. He told me himself that he doesn’t sleep at night, worrying about his workers and their families, and he was very sincere. I might have been skeptical once, but I can’t deny he’s always rehired as many as he could when copper prices went up again.”

In their discussions, Finlay had expressed his own worry about losing his job. In recent weeks, copper prices had fallen to just eight pounds per ton, but Mr. Mason had reassured him that Finlay’s job was still secure.

“I’m delighted you have found a friend in Mr. Mason,” Abbey said, hoping to soften the blow of her next statement. “But I love Neal Tavis, and one day we will wed.”

Finlay was alarmed to hear this news, especially as he’d already voiced his objections. He had assumed that the infatuation between the two had ended. But Abbey thought it was high time he got used to the idea that she intended to wed for love, not financial security.

“I know you aren’t pleased with that idea, but you must forget any notions of me marrying an old man for his money,” Abbey said when she saw his expression.

Finlay erupted. “I’ll not see my daughter marry someone destined to be poor,” he growled. “I want more for you than a future in a dugout.”

“Neal plans to buy a farm one day, Father. So, we’ll have a home.”

Finlay shook his head as painful memories flooded his mind. “Can you not remember how hard life on a farm can be, Abbey? And Neal is burdened with supporting his mother and sisters. That’s no way to start your married life.”

Abbey was remembering something, too. After her mother had died, her father had suffered a complete breakdown. Losing his wife, on top of two children, had sent him spiraling into a deep depression. Most mornings he couldn’t drag himself from bed. If he did, he got drunk, so they were soon evicted from the farm they’d been tenanting. Her father’s sister had taken them in. Her father and Abbey had then lived with Aunt Brigit, her husband, and her family of five children on their farm in Galway. They had endured those miserable cramped conditions for three years, which was how long it had taken her father to recover. When Brigit had heard about an opportunity for miners in Australia, she had given her brother a much-needed push, and he and Abbey had set off to begin a new life in the colonies. That had been almost three years ago.

At first, her father had held high hopes of making his fortune in the mines and buying a nice cottage in town. He’d even considered opening a business, but things hadn’t progressed as quickly as he would have liked. For one thing, due to the huge influx of miners in the beginning, there was a shortage of cottages. Life as a miner also meant hard work in dangerous conditions, and the pay wasn’t as good as her father had expected. Frustrated that he couldn’t provide for his family, he fell once again into depression. He started drinking and gambling, which meant the money dwindled away even faster.

“I don’t want my daughter cleaning pigsties and chicken coops, held hostage by the rain in a country where droughts are common for years on end. Life on a farm is too damn hard unless you’ve got money to see you through the tough times. I want you married to a man who can look after you better than I looked after your mother.”

“You did the best you could. The potato famine and her sickness weren’t your fault,” Abbey said, trying to quell his anger.

“Maybe not, but if you have a choice between a hard life and an easy life, you’d be a fool to make the wrong choice. You’ve been blessed with a pretty face, Abbey, so make the best of it.”

Abbey was horrified that her father would suggest she use her looks to snare a rich husband, and Finlay could see it.

“Is it so wrong to not want my daughter to suffer?” he asked angrily.

“No, Father, but you must let me make my own choices.”

“You can’t be trusted to do that. Not when you fall for the first young man who glances in your direction, and one who’s destined to be penniless at that.”

Abbey’s quick temper flared. “Neal is a good man, and he makes me happy.”

“There are many kinds of happiness, Abbey. If Mr. Mason wants to marry you, then that’s what you’ll do. One day, when you’re wearing fine clothes and entertaining guests in a fancy drawing-room in Martindale Hall, you’ll thank me.”

“No, I won’t, and I’ll not crawl into a marital bed with an ogre like Ebenezer Mason. I don’t care how much money he has. How could my own father suggest such a thing?”

“It’s better to have servants, than to be one, Abbey. We’re going to dine at the Hall, and that’s that,” Finlay said angrily.

“I’d sooner be poor and scratching in the dirt every day beside the man I love, than to endure a lifetime of unhappiness just so I could have servants,” she retorted.

“What nonsense,” Finlay slurred, yawning. It had been a long day, and the beer he’d drunk at the pub was draining him of all energy. His eyelids started to flutter.

Abbey scrambled to her feet and fled outside, blinded by her tears. As she made her way down Creek Street, she could just hear her father shouting that she make sure her best dress was clean so she could wear it to the Hall on Saturday. She hurried toward Neal’s dugout. When she got there, she called to him from outside.

Neal’s father had died of a suspected heart attack two weeks after the family had arrived in Burra, leaving them stranded with no money. It had been devastating, especially as his mother, Meg, was often ill. Neal had been forced to start work in the mine before his fifteenth birthday. When she was well enough, Meg did washing at a laundry in Burra, which earned her a few shillings. Without Neal’s wages, though, the family would have been in ruins.

Neal came out of the dugout. His hair was sandy blonde and framed his face with a few slight curls. He had a gentle and quiet air about him. Abbey launched herself into his arms.

“What’s wrong, Abbey?” Neal asked.

Abbey held onto him for a few moments. She couldn’t bring herself to admit that her father wanted her to court the likes of Ebenezer Mason. It was too horrible and humiliating.

Neal felt her shudder, unaware that it was a shudder of revulsion. “Has something happened, Abbey?” he asked, pulling slightly away from her so he could see her tear- stained face in the moonlight.

Abbey found comfort in the depths of his warm brown eyes. She couldn’t break his heart and tell him her father would never accept a marriage between them. “Little Ely Dugan has just passed away,” Abbey said as tears welled in her blue eyes again, making them sparkle.

“Oh, no,” Neal said. “I’m so sorry, Abbey. I know how fond of him you were.”

Abbey nodded. “Let’s elope, Neal,” she blurted out. “Let’s run away and get married.”

Neal looked startled. He glanced over his shoulder. His mother was just inside the dugout with his sisters, so he took Abbey’s hand, and they walked along the creek bed. “You know I love you, and I want to marry you, Abbey, but I can’t run off and leave my mother and sisters. Where would they be without me?”

Neal was right, and Abbey appreciated his loyalty and sense of responsibility. There was so much she loved about him, aside from the fact that he was, in her opinion, exceedingly handsome. She knew that he wasn’t free to do as he wished.

“Then let’s get married and stay here until we can afford to move,” Abbey said. It wasn’t an ideal situation, but anything was better than having to marry Ebenezer Mason.

“Has something happened, Abbey? I’d like to believe you suddenly can’t wait for the joys of marriage, but I don’t think that’s true.” He smiled at her, and Abbey felt her heart melt. She touched his hair and returned his engageing smile, but she couldn’t tell him the truth. Instead she leant against him, resting her head on his shoulder.

“I just want to be your wife,” she whispered.

“And I want to be your husband,” Neal said, kissing her cheek softly. “We’ll get married soon, Abbey. I’m putting a little away each week so that we can afford a minister and a nice wedding breakfast.” To help save on expenses, his mother had given him his grandmother’s wedding band for Abbey.

Abbey brightened. “Are you, Neal?” she asked excitedly.

“Yes,” he said, enjoying her innocent joy. “Now stop worrying. By the middle of next year, we’ll be husband and wife. I promise.” He was looking forward to it as much as she was. He also knew in a few years his sisters would be working, and their income would help support the family and lighten his burden.

“Oh, Neal,” Abbey said, hugging him again. “I do love you.” He’d given her something wonderful to look forward to, and, additionally, the strength to face whatever she must in the meantime.

When Abbey got back to her and her father’s dugout, her heart was a little lighter. Her father was snoring loudly, and, as she looked at him, Abbey sighed. If he insisted, she’d have to dine with him at the Hall, but she was determined to be as horrid as she could, so that Ebenezer Mason would forget any ideas he might have about marrying her.

CHAPTER 2

The next morning Abbey didn’t awaken until after her father had gone to work. She’d had a restless night because of the heat and her father’s snoring, yet she still felt ashamed that she hadn’t made him breakfast. She could see he’d eaten a piece of the bread she’d cooked the previous evening, but that wasn’t enough to sustain him through a hard day at the mine. She felt even guiltier when she found the shilling he’d left her to buy food. It distressed her to think he was serious about her courting Ebenezer Mason, but she tried not to dwell on it. Instead, she’d think about her future life with Neal.

The morning progressed in the usual fashion, but as Abbey went about doing some washing and collecting firewood, she had the terrible feeling that something wasn’t right. As no more of the children in the near vicinity were ill, she put it down to the fact that she had argued with her father. She intended to apologise to her father because she hated any ill feeling between them. She knew that he only wanted the best for herif only he understood that Neal was the best.

I’ll go to the bakery and get Father a steak and kidney pie for dinner, she thought. They couldn’t really afford such a treat, but she wanted to make up for being disrespectful, and, hopefully, she could sway her father into letting her marry Neal. I’ll get a bottle of ale to go with it, she thought. Father will love that.

***

It was a sweltering day, with a north wind that carried dust across the parched countryside. Abbey was in town at the bakery when she heard the steam-whistle at the mine. There must have been an accident, a cave-in, perhaps.

Everyone started running towards the mine, including Abbey. She could hear the whistle blaring the entire way, and her heart pumped wildly. Suddenly the strange sense of foreboding she had suffered all day made sense. Sometimes up to four hundred men worked below ground at one time; a cave-in or similar accident could spell disaster.

By the time she got to the mine, Abbey was gasping for breath, and perspiration bathed her skin. What seemed like hundreds of people had gathered by the entrance: wives and children with husbands and fathers employed at the mine, miners from different shifts, and shopkeepers who depended on the money the mine brought to the town.

“What’s wrong? What’s happened?” Abbey gasped, trying to push through the throng. “Has there been a cave-in?”

“The Morphett Engine failed, and one of the mine shafts has filled with water,” someone told her. “The water will soon spread to the other shafts.” It was a man about the same age as her father, a mine employee, and his face was ashen. His work clothes were wet and streaked with mud, and one cheek was grazed. “I was just coming out of the shaft … so I was lucky,” he added breathlessly. He pushed through the crowd before she could question him further to find out if anyone else had escaped.

Abbey was faint with fright as she imagined her father and Neal underground, drowning. She felt the blood drain from her face, and her legs almost buckled beneath her. Her father had often spoken of the importance of the Morphett Engine. It was used to pump underground water from the mineshafts, keeping them clear for the workers. If it failed, the mine could quickly fill with water.

Abbey grabbed the sleeve of another worker. “How many men have come out? Has anyone seen my father, Finlay Scottsdale?” She frantically searched the faces around her, wanting to call out for her father but terrified he wouldn’t answer her.

“By some miracle, quite a few men got out—they were just coming up for a break when the Morphett Engine failed,” the miner told her. “You hold the faith, girlie.” He gripped her arms and stared into her face intently. “Everything will be fine.” He let her go and disappeared.

Abbey desperately wanted to believe he was right, but she said a silent prayer, anyway, that her father and Neal were amongst the miners who had been coming to the surface when the engine had stopped working. Tears streamed down her face, and dread settled in the pit of her stomach.

Abbey thought about the argument she’d had with her father. She regretted being terse with him, and she desperately wanted the chance to set things right.

“If you’re alive, I promise I’ll be a better daughter,” she whispered. And she meant it with all her heart.

Abbey wandered through the crowd, searching the dirty faces for her father or Neal. But she couldn’t find either of them.

Suddenly, she jumped when someone clutched her arm.

“Father!” she said and turned, her heart leaping with joy. But instead of her father, she was confronted with Neal’s mother’s worried face.

“Where’s my Neal?” Meg Tavis asked through her tears. She was a sickly woman and terribly pale.

“I don’t know,” Abbey uttered breathlessly as her eyes welled with more tears. “And I can’t find my father.”

The two women clung to each other in shared grief and worry, and waited.

Sodden miners were being pulled from a shaft, one by one. They were spluttering and gasping for air. Abbey couldn’t bear to think about how terrified her father would be. She thought about how he had never liked water, not even being on the ocean in a boat. He’d hated every minute of their journey to Australia.

More men were dragged from the shaft, and several of them had to be revived. Their loved ones took them in their arms, crying with relief. Abbey and Meg knew every second was crucial, so they were in agony. As each man was dragged out, the women squeezed each other’s hands, praying that they’d see Finlay or Neal.

The miners above ground were frantic to save the men in the shaft below. Several were working feverishly on the engine, desperately trying to bring it to life. The bystanders, who could only watch helplessly, were pushed back so the men had room to move and work. Abbey could hear people uttering prayers out loud. Most of the women and children were sobbing.

Suddenly a joyous noise broke the air. It was the Morphett Engine spluttering to life. For a moment there was silence, and then a roar of applause.

“They’ll be all right now, Mrs. Tavis,” Abbey said to Neal’s mother. She was smiling and crying at the same time, overjoyed, refusing to imagine any other outcome.

Meg’s pained expression softened a little. “I won’t believe it until I see my Neal’s face,” she whispered. “Please, God, spare him and Finlay.”

Abbey put her arms around Meg’s shoulders and squeezed, trying to comfort her. She felt the same. All she wanted was to see her father’s and Neal’s faces. She prayed harder than she ever had in her life.

Another few miners were brought to the surface. They were dripping wet and so dirty that it was difficult to identify them. Women surged forward, calling their loved ones’ names. Each time, it was agony for Meg and Abbey as they waited for Finlay and Neal. They were happy for the families of the men who were brought up, but with every minute that passed, it was harder to keep hoping.

Suddenly the Morphett Engine sputtered and died again.

“Oh, God no,” Abbey cried, her heart sinking. Men were shouting instructions and dashing about. In desperation and with no time to waste, several ran back into the shaft against the manager’s orders, diving down into the murky depths to search for lost miners. Meg and Abbey waited, hardly breathing, until the men came back again. Twice a man was brought to the surface and revived, coughing up dirty water, but neither man was Neal or Finlay.

As the minutes dragged on, the two women became weak with anxiety. Someone reported that there had been a partial cave-in caused by the flooding. This was the worst possible news.

“How many are down there now?” Abbey asked a miner nearby.

“We’re not sure,” he said. “Someone is doing a head count.”

A woman pushed forward to the mine’s entrance, calling for her husband. Two miners took hold of her as she sobbed with grief. Fifty-eight miners had been in the flooded shaft. As far as anyone knew, most had gotten out. Jock McManus, the crying woman’s husband; Finlay; and Neal still hadn’t been accounted for, along with possibly two or three others. Apparently, the miners had dug through to a large source of underground water at exactly the wrong time, and the Morphett Engine had failed.

Meg Tavis broke free of Abbey’s grasp and pushed forward, only to be stopped. “Where’s my son?” she cried, beating the chest of the man who had prevented her from getting too close to the shaft. “Where’s my Neal? Save him!” she screamed. “You have to save him.” For a few moments, she became wildly frantic, and then she collapsed, fainting.

Suddenly the Morphett Engine spluttered to life again.

“Thank you, God,” Abbey whispered, tears running down her cheeks. She imagined an air pocket in the shaft and Neal and her father in it, waiting to be saved. She absolutely believed it must be true. She went to Meg’s side and took her limp hand.

“They’ll be out in a minute, Mrs. Tavis,” she said. “You’ll see. Father and Neal will be safe.” Abbey was sure everything would be all right. It had to be. She’d lost her mother, brother, and sister. She couldn’t lose her father, too.

It seemed to take an eternity to drain the mineshaft. As soon as the water had receded enough, several men went in to look for the missing miners. Abbey left Meg’s side and went as close to the entrance as she could. She wanted to be there when her father came out. She wanted to be the first person he saw. Time dragged on mercilessly, but Abbey was certain her father would be all right. She intended to berate him for frightening her witless, and she also intended on insisting that he stop working in the mine.

Ten minutes passed, and there was no sign of the missing men or their would-be rescuers.

“Where are they?” Abbey asked a miner standing nearby. “What’s taking so long?”

“They have to be cautious,” the miner told her. “The shafts will be unstable.”

Abbey caught a hint of concern in his tone, and it worried her, but she saw no reason to give up hope. Her father and Neal were all right. She knew it in her heart. God wouldn’t be so cruel as to leave her alone in the world. He wouldn’t do that.

The waiting was absolutely unbearable, but finally men began to come out. They were soaked and looked exhausted. Abbey was joyous with relief, yet still she searched frantically for her father’s or Neal’s face.

“Where’s my father?” Abbey called to one of them. “Have you found Finlay Scottsdale or Neal Tavis?”

The miner came to stand before her. “We found them,” he said solemnly, placing his hand on her shoulder.

His words made Abbey’s heart leap with joy. “Where are they? They’re not hurt, are they?”

The miner said nothing. Abbey noticed his eyes were sorrowful, and the glimmer of hope inside her snuffed out. He stepped aside, and Abbey saw that his comrades were carrying three men, their bodies lifeless as they were placed side by side on the ground. First Jock McManus, then her father, and, finally, Neal.

Abbey could only stare at their lifeless bodies. Judy McManus threw herself over her husband, sobbing. All around her Abbey heard mumbles, accusations against Ebenezer Mason for not spending the money needed to maintain the Morphett Engine. The conversation she’d had with her father the night before kept playing in her mind. Just hours ago, he’d suggested she court the man who was now responsible for his death.

When the crowd around her dispersed, Abbey stumbled forward and looked down at her father’s face as he lay lifeless beside Neal and Jock. No. No. No. This wasn’t the way it was supposed to be. Abbey had imagined herself throwing her arms around her father and Neal, sobbing tears of joy. This can’t be happening, she thought. It’s not real.

In death, Neal looked like a young schoolboy between the two older men.

“Neal” Abbey whispered, tears streaming down her cheeks. Her heart ached with agony. Neal was gone. They would never have a family together. She cried for Neil and for the babies she’d never have with him. Abbey noted that the three men were a strange colour, but she still couldn’t grasp that they were dead. It didn’t seem possible.

“Father,” Abbey whimpered, bending to touch his face, which was icy cold despite the heat of the day. In the background she could hear Meg’s hysterical sobs.

“Don’t leave me all alone, Father,” she whispered. “I need you. Please, don’t leave me.”

***

In the hours that followed, Abbey was in a daze. She was vaguely aware of being escorted back to her dugout by one of the miners, and of him telling her that her father’s body would be taken to Herman’s Funeral Parlor, where Herman Schultz would prepare it for burial. A trickle of local women stopped by her dugout to offer sympathy, but Abbey barely acknowledged them. It wasn’t until one of her father’s friends encouraged her to drink half a flask of whisky that evening, that she was able to pull herself together and stop crying long enough to think about Neal’s mother and sisters.

Almost in a trance, Abbey headed for the dugout where Neal had lived. She was worried about Meg because of her fragile health. Abbey hadn’t been in a frame of mind to consider what she herself would do, or how she would support herself, but she couldn’t help worrying about how Meg and the girls would cope without Neal.

Abbey was startled to find the dugout deserted and all their belongings gone. She didn’t know what to think.

“Are you looking for Meg, Abbey?” Vera Nichols from the dugout next door asked.

“Yes, Mrs. Nichols,” Abbey said. “Do you know where she is?”

“I thought you would have heard that she’s been taken by dray to the hospital in Clare. A doctor was called to the mine.”

“No,” Abbey said in disbelief.

“I’m very sorry about your father, love,” Vera said sadly.

Abbey could only nod as tears ran down her cheeks, but Vera understood.

“I brought my Dennis home after they pulled him out of the mine, so I didn’t see Meg before she was taken away. I was told that she had taken her son’s death very badly, and apparently she’s very ill.”

Abbey felt racked with guilt. She sniffed and blew her nose. “What about Mr. Nichols?”

“He’ll be fine, but it’s a miracle. Beatrice Smythe told me Meg’s in a very bad way and might not live,” Vera added gently. She thought it was better to be honest with Abbey, rather than hide the truth of the situation. “Apparently, the doctor thinks her heart may be failing. Not surprising, is it?” she sighed raggedly.

“Where are Mrs. Tavis’s possessions and clothes, and the girls’?” Abbey asked. They hadn’t had much, but even Neal’s clothes were gone, although Abbey couldn’t bring herself to mention him for fear her tears would come again.

“Beatrice and I packed everything up and stored it in her home. It wouldn’t take long for the scavengers to move in if the dugout was empty for a few days, and then everything would be gone.”

“Oh,” Abbey said. She couldn’t stop thinking about Meg. In deserting her, Abbey felt she had let Neal down. “I should have made certain she was all right. I shouldn’t have left her.”

“Don’t blame yourself, Abbey. Meg knows you are in shock, and you have your own pain to deal with. She’s never been very strong, so it wouldn’t be surprising if her health couldn’t withstand something like this.”

“What about Amy and Emily? Who is looking after them?” Abbey asked, brushing away the fresh tears sliding down her cheeks. The twin girls were only eleven years old.

“They went with Meg,” Vera said. “If Meg does pass away, God forbid, I suppose they will be taken to an orphanage in Clare or sent to one in Adelaide. They have no family here in Australia, and none of us are in a position to take them in. It’s a terrible tragedy. Let us just pray they aren’t separated. That would be awful.”

Abbey couldn’t bear to think about how distraught and afraid Amy and Emily would be after losing their brother and now having their mother so ill. Pain washed over her again, and she collapsed in the dust at her feet.

Vera always tried her best to be stoic, as it was the only way she could cope with so much heartache around her, but witnessing Abbey’s sorrow was almost her undoing. She knew what she’d been through that day, and Abbey was too young to cope with so much loss.

Kneeling beside Abbey as she sobbed, Vera put a comforting arm around her shoulder. “There, there, dear. It’s been a terrible day for you, hasn’t it?” she said emotionally. “I know you loved Neal and to lose your father, as well” She pursed her thin lips. “That Ebenezer Mason has a lot to answer for. But you have to pull yourself together and go on, Abbey. There’s nothing else you can do.”

At the mention of the mine owner’s name, Abbey lifted her head and braced her shoulders, reminding herself that she had somewhere to direct her pain and anger. But first she had to see to it that her father received the burial he deserved.

***

After closing time at the Miner’s Arms, Paddy Walsh, one of Finlay’s closest friends, visited Creek Street.

“I’ve come on behalf of the regulars at the Miner’s Arms, Abbey. Please accept our deepest sympathy,” he said gravely. He was holding his cap. “Yer father was a fine man, a gentleman and a real good mate. It mightn’t help much, but I took up a collection.” He self-consciously removed a few pounds and some loose coins from his cap and handed it to her. “I know it’s not much, but we hope it helps with the funeral costs. If ye let us know when it is, we’ll be there, and afterwards there’ll be a wake at the pub, which yer welcome to attend.” He cleared his throat, as his voice was cracking with emotion.

Abbey was aware of the close relationship between her father and his friends, but she could also see that Paddy had drunk more than his fair share of beer before coming to see her.

“Thank you, Mr. Walsh,” she said in a shaky voice. She wasn’t comfortable taking money from her father’s friends, but she was in no position to refuse.

Abbey had been visited by one of the town’s two undertakers that afternoon, so she knew what a decent funeral for her father would cost. The few pounds collected by Paddy wouldn’t cover it. Pride prevented her from saying anything, however. She was more determined than ever to ask Ebenezer Mason to pay, because he was responsible.

“I never liked the idea of your father working at the mine,” Paddy said. “I always said it was too bloody dangerous to be underground. Your father knew it, too, but he was afraid to leave the mine in case he couldn’t get anything else.”

Paddy’s words made Abbey feel even guiltier. If her father had been afraid to leave the mine and look for work elsewhere, it must have been because he had her to consider. For the first time, it occurred to her that perhaps she’d been a real burden on him, and this only added to her despair.

“Have ye thought about what you’ll do now, Abbey?” Paddy asked gently.

“No, I haven’t,” she admitted. “I suppose I’ll have to look for work. My father would never let me when he was alive.” She almost broke down. “He said it was my place to look after him until I married.” Thinking of Neal, Abbey couldn’t hold back the tears.

“Keep your chin up, lass,” Paddy said awkwardly. “I know it must be hard. My landlady, Mrs. Slocomb, might be looking for a cleaner,” he said. “If ye can’t find anything better, go and see her.”

After Paddy had gone, Abbey curled up on her burlap bed on the dirt floor of the dugout, hoping to sleep, but she’d never felt more lonely or afraid in her life. At least after losing her mother, she had still had her father. Now she had no one. Not a soul in the world, or at least in Australia. She certainly didn’t have the means to return to her aunt and uncle in Ireland. Her heartache was overwhelming. And it was all Ebenezer Mason’s fault. She couldn’t understand why someone with so much money wouldn’t protect his workers by maintaining the equipment used in the mine. It was criminal as far as she was concerned. If she had her way, he’d be locked up in the Redruth Jail. But she knew that would never happen. He was too revered in the district of Burra, and she’d heard talk that he had every constable in town in his back pocket.

***

Abbey cried off and on until the sun came up, so she was exhausted the next morning, but a sense of purpose motivated her to get up. She was just about to leave for the mine, to confront Ebenezer Mason, when the undertaker, Herman Schultz, arrived.

“It’s going to be very hot, Miss Scottsdale, so we will have to conduct your father’s funeral today, rather than tomorrow, as planned,” he said apologetically.

“Today?!” Abbey gasped.

“Yes, this afternoon at the latest.”

“But I don’t have enough money for a coffin or headstone yet,” Abbey told him.

“We’ll do the best we can with what you’ve got,” Herman said sympathetically. “The casket will have to be a simple pine box, and you can make the grave marker yourself.”

“What about Neal Tavis?” Abbey asked in a shaky voice. “His mother’s been taken to hospital in Clare, so who will bury him?”

Herman looked pained. “Mr. Tavis will be given a pauper’s burial,” he admitted sadly. In such cases the Burra Shire Council paid Herman a token fee.

Abbey gasped. “That’s not right,” she said angrily. “The mine owner should be paying for a good burial for my father, Neal, and Jock. It’s the very least he could do.”

“I cannot approach anyone at the mine and ask for money, Miss Scottsdale,” Herman said. “It’s not my place.”

“Well, I can,” Abbey snapped. “And that’s just what I intend to do. I want my father to have the bestand Neal, too. I’ll get the money, you’ll see.”

Herman looked uncomfortable. “I must get paid, Miss Scottsdale. I’ve got a large family to feed.”

“You will,” Abbey promised determinedly.

Herman Schultz didn’t know Ebenezer Mason personally, but since opening his business in Burra five years ago, there had been twelve deaths at the mine, and the mine owner had never offered to pay for any of the funerals. As such, he thought Abbey had very little chance of getting any money. “I’m sorry, Miss Scottsdale, but I’ll require payment before the funeral,” he said, embarrassed.

“I understand,” Abbey said resentfully.

She went straight to the mine, but at the office was told that Mr. Mason wasn’t there. “Then, where is he?” she demanded of the office assistant, Mrs. Sneebickler. “I’m not leaving until I see him.”

Mrs. Sneebickler was a no-nonsense type of woman, well- suited to working in the masculine environment of a mining company. She ruled her office with an iron fist, and normally not even the toughest brute got anything past her. But when faced with a forlorn, grieving young girl who’d just lost her father, and who just wanted some answers and help, her steely resolve deserted her.

“Go home, Abbey, and come back tomorrow. Mr. Mason might be here, then,” she said firmly but compassionately. “There’s nothing I can do.”

Abbey stood her ground. “If Mr. Mason isn’t here, I want to see whoever’s in charge,” she said, fighting tears. “I won’t leave until I speak to someone who can help me.”

Seeing that the girl was on the verge of hysterics, Mrs. Sneebickler relented. She’d liked Finlay Scottsdale, who had always been respectful and courteous, even when she’d been short with him.

“The mine’s manager is here. He’s very busy, but I’ll see if he’ll come to the office.”

“Thank you,” Abbey said, fighting tears. Just being at the mine so soon after the accident was difficult for her.

Mrs. Sneebickler sent someone to fetch Frank Bond to the office.

***

Knowing that his boss wouldn’t stand for the mining operation to be stopped for very long, Frank Bond had been supervising work on the Morphett Engine, and it wasn’t going well. He was agitated at being disturbed and was ready to lose his temper by the time he got to the office.

It wasn’t until he was confronted by Abbey, whose eyes were full of tears, and was told that she wanted Ebenezer Mason to pay for his employees’ funerals, that he calmed down. Frank told her that he sympathised, but that he couldn’t authorise any type of compensation unless he spoke to Ebenezer Mason first.

“Then, where is he?” Abbey demanded.

“As far as I know he’s at his home in Mintaro, Miss Scottsdale,” Frank explained uncomfortably.

Mintaro was about fifteen miles away, which meant Abbey didn’t have enough time to get there and back before her father’s funeral. Besides, she didn’t own a horse and buggy and couldn’t afford to rent one.

“Doesn’t he know that three of his employees have been killed?” Abbey couldn’t believe he’d stay at home after such a tragedy.

“We sent word immediately after the accident,” Frank said, embarrassed. “But so far, we haven’t heard from him.” Frank was actually very angry with his boss for not coming to Burra immediately after receiving news of what had happened, but he was powerless to do anything about it. Ebenezer Mason had always been aloof and detached from his workers. Unless he had a specific reason, he hardly ever spoke to them. His priority was the profitability of the mine, the results of which he used to support his lavish lifestyle.

“That’s not good enough,” Abbey declared. “My father and Neal must be buried today because of the heat.” She was barely holding herself together.

“I’m very sorry, Miss Scottsdale.” Frank Bond was genuinely regretful. “But there’s nothing I can do.”

Abbey could see the guilt in his features, but it didn’t soften her heart. She was sure he was aware of his boss’s poor safety practices. A small part of her understood that he wouldn’t say anything for fear of losing his job, but if no one spoke out, more lives would be lost. Somebody had to take a stand.

“That Ebenezer Mason hasn’t come to the mine to speak to his workers’ families is appalling, cowardly behaviour and absolutely unforgivable, as far as I’m concerned,” Abbey stated.

Frank Bond couldn’t disagree. “As your father’s only kin, you can take what’s owed to him,” he said. “It’s not much because he was paid yesterday, but I’m sure every penny helps at a time like this.” His cheeks were flush with shame. He’d been put in this position too many times, and it only seemed to get harder and harder. He left Mrs. Sneebickler to pay Abbey.

“I’m very sorry about your father, Abbey,” she said. “Will you be all right on your own?”

“I’ll have to be,” Abbey said tersely. “Nothing will bring him back.”

Abbey took the few shillings, more than she was actually due, a kindness from Mrs. Sneebickler, and bought some flowers to put on her father’s and Neal’s graves.

CHAPTER 3

Before Finlay’s funeral service began, many miners came up the road to the cemetery to see their fellow miner off. They were a sombre group, but Abbey was moved to see them. And, then, at three o’clock and in blistering heat, Abbey walked to the cemetery beside a waggon that was carrying her father, four of her father’s friends accompanied her. Abbey had been forced to settle for one of the cheapest pine boxes. It broke her heart, but for his sake, she held her head high.

She’d told Vera that Neal was to be buried at four thirty, and she’d promised to be there with a few of Meg’s other neighbours. Abbey had been told that Jock McManus was also to be buried later that day, but in another cemetery in Aberdeen, the Scottish quarter of town. Burra was essentially made up of several small townships, collectively known as The Burra. They included the South Australian Mining Association’s company town of Kooringa; Redruth, where most of the Cornish people lived; Aberdeen, the Scottish quarter; Llwchwr, where the Welsh people congregated; and Hampton, which was mostly English. Scattered throughout The Burra were a few other nationalities, including quite a few Irish.

The Catholic priest in town spoke about Finlay’s life, which, when summarised, sounded short and tragic. When he spoke of him as a man, and how highly he was thought of amongst his fellow miners and friends, and what a good father he’d been to Abbey, she felt a sense of pride, as well as deep sadness and loss. When the mourners left the cemetery for a quick beer at the pub, promising to come back for Neal’s service, she had a quiet moment to say a heartfelt, tearful goodbye to her father before the undertaker’s assistant filled in the grave. She then placed some of the flowers on the grave before waiting under the shade of some eucalyptus trees for Herman to bring Neal’s body up to be buried.

The main Burra cemetery was on a hill that rose above the township. But from there Abbey had a clear view of the Monster Mine on a brown hill in the distance, and her resentment grew. She wished her father didn’t have to spend all of eternity overlooking the mine that had claimed his life. It didn’t seem right.

“When I can afford it, Father, I’ll have you moved somewhere much nicer,” she vowed tearfully. And she meant it.