9,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

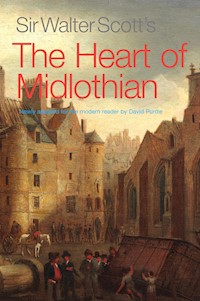

- Herausgeber: Luath Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

If a sister asks a sister's life on her bended knees, they will pardon her; and they will win a thousand hearts by it. Edinburgh, 1736: Captain John Porteous is charged with murder and locked up in Edinburgh's Tolbooth prison, also known as the Heart of Midlothian. When news comes that he has been pardoned, a baying mob breaks into the jail, liberating its inmates and bringing Porteous to their own form of justice. But one prisoner, Effie Deans, chooses not to take the opportunity to flee. Wrongly convicted of murder, Effie has been sentenced to death. Jeanie, her older sister, sets about walking to London to beg for her pardon from the queen. A gripping tale of religious piety and filial devotion, this new edition of The Heart of Midlothian has been expertly reworked for modern readers by David Purdie.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 496

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

PROFESSOR DAVID PURDIE was born privately and educated publicly at Ayr Academy and Glasgow University. Now a disused medical academic, he devotes what time is left to writing, lecturing and broadcasting.

He is a parliamentary speechwriter and editor for several truthful MPs, and for a limited number of sporting and show-business personalities. David is Editor-in-Chief ofThe Burns Encyclopaediawhich deals with the life and work of the poet Robert Burns and is Chairman of the Sir Walter Scott Club of Edinburgh. He has a long-running humorous columnThe Majorin the magazineGolf Internationaland is preparing a translation of the works, on religion, of the philosopher David Hume.

He is in considerable demand as an after-dinner speaker, described in this role by theDaily Telegraphas ‘probably our best of the moment.’ He lives in Edinburgh.

Sir Walter Scott’s

The Heart of Midlothian

Newly adapted for the modern reader by

David W. Purdie

LuathPress Limited

EDINBURGH

www.luath.co.uk

First published 2014

ISBN: 978-1-908373-80-9 PBK

ISBN: 978-1-908373-81-6 HBK

ISBN: 978-1-909912-46-5 EBK

eBook 2014

The author’s right to be identified as author of this book under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 has been asserted.

© David W. Purdie

Table of Contents

chapter one

chapter two

chapter three

chapter four

chapter five

chapter six

chapter seven

chapter eight

chapter nine

chapter ten

chapter eleven

chapter twelve

chapter thirteen

chapter fourteen

chapter fifteen

chapter sixteen

chapter seventeen

chapter eighteen

chapter nineteen

chapter twenty

chapter twenty-one

chapter twenty-two

chapter twenty-three

chapter twenty-four

chapter twenty-five

chapter twenty-six

chapter twenty-seven

chapter twenty-eight

chapter twenty-nine

chapter thirty

chapter thirty-one

chapter thirty-two

chapter thirty-three

chapter thirty-four

chapter thirty-five

chapter thirty-six

chapter thirty-seven

chapter thirty-eight

chapter thirty-nine

chapter forty

chapter forty-one

chapter forty-two

chapter one

Who has e’er been at Paris must needs know the Grève,

The fatal retreat of th’ unfortunate brave,

Where honour and justice most oddly contribute,

To ease heroes’ pains by an halter and gibbet.1

Matthew Prior,The Thief & Cordelie: A Ballad

In former times, England had her Tyburn, to which the victims of justice were conducted in solemn procession along what is now Oxford Street. In Edinburgh, the Grassmarket, a large open street or rather an oblong square, surrounded by high houses was used for this purpose. It was not ill-chosen for such a scene, being fit to accommodate the great number of spectators usually assembled. Few of the houses which surround it were, even in early times, inhabited by persons of fashion or those likely to be offended or even affected by such exhibitions. The place itself is not without some features of grandeur, being overhung by the southern side of the huge rock of the Castle and by the battlements and turreted walls of that ancient fortress.

It was thus the custom to use the Grassmarket esplanade for public executions, the fatal day being announced to the public by the appearance of a huge black gallows tree towards the eastern end. This apparition was of great height, with a scaffold surrounding it and a double ladder placed against it for the ascent of both criminal and executioner. As this was always arranged before dawn, it seemed as if the gallows had grown out of the earth in the course of one night, like the production of some foul demon. I well remember the fright with which schoolboys, when I was one of their number, used to regard these ominous signs. On the night after the execution the gallows disappeared again, conveyed in darkness back to the vaults under Parliament House. This mode of execution has now been exchanged for one similar to that in front of Newgate Prison, though with what beneficial effect is uncertain. The mental sufferings of the convict are shortened; he no longer stalks through a considerable part of the city between attendant clergymen, dressed in his grave-clothes and looking like a walking corpse.

On the 7th day of September 1736, preparations for execution were descried in the Grassmarket. At an early hour the area began to be occupied by several groups who gazed on the scaffold and gibbet with an unusually stern show of satisfaction. Such is seldom shown by a populace whose good nature usually forgets the crime of the condemned and dwells only on his misery. However, the very act for which this condemned man had been convicted had awakened the highest resentment of the multitude. The tale is well known; yet it is necessary to recall the circumstances to better understand what follows.

The contraband trade, though it strikes at the root of government by encroaching upon its revenues and injuring the fair trader, is not usually looked upon by either the commonality or their betters as particularly heinous. On the contrary, in those countries where it prevails, the boldest and most intelligent of the peasantry are engaged in such illicit transactions, often with the approval of the farmers and gentry. Smuggling was almost universal in Scotland in the reigns of George I and II because the people, unused to taxes and regarding them as an invasion of their ancient liberties, had no hesitation in evading them.

-----------

1 La Place de Grève (‘gravel square’) was the site of public executions under theancien régime. Now La Place de l’Hôtel de Ville, it is the square in front of City Hall.

chapter two

[Fife]Ane beggaris Mantle, fringit wi’ Gowd1

King James VI & I

The county of Fife is bound by two firths to the south and north, and by the North Sea to the east. Having a number of small seaports, it was long famed for its successful smuggling trade and harboured many seafaring men who had been buccaneers in their youth. Among these, one Andrew Wilson, originally a baker in the village of Pathhead, was particularly obnoxious to the Revenue Officers. He possessed great personal strength, courage and cunning and was perfectly acquainted with the coast. On several occasions he succeeded in eluding the pursuit of the King’s Officers, but became such an object of their attention that he was finally ruined by repeated seizures. The man became desperate. He considered that he himself had been plundered and took it into his head that he had a right to make a reprisal.

Having learned that the Collector of the Customs at Kirkcaldy was to be in Pittenweem carrying a considerable sum of money, Wilson resolved to reimburse himself for his losses. Accompanied by a certain Robertson and two other young men in the smuggling trade, he broke into the house where the Collector lodged. Wilson and his two accomplices entered the Collector’s apartment while Robertson kept watch at the door with a drawn cutlass. The Collector, believing his life in danger, escaped through his bedroom window while the thieves stole about two hundred pounds of public money. The robbery was particularly audacious, as several persons were passing in the street at the time. Robertson, however, assured them that the noise they had heard was just a dispute betwixt the Collector and the people of the house. The worthy citizens of Pittenweem felt themselves in no way obliged to interfere on behalf of the obnoxious Revenue Officer and, like the Levite in the parable: The Good Samaritan: Luke 10.29–37 passed by on the opposite side. The alarm was at length raised and the military were called in. The robbers were pursued and captured, the booty was recovered and Wilson and Robertson were tried and condemned to death by hanging.

Many citizens thought that justice might have been satisfied with less than the forfeiture of two lives. The Government’s opinion, on the other hand, was that the audacity of the raid required that a severe example be made. When it became apparent that the sentence of death would be executed, a friend outside succeeded in smuggling files and other implements into the prison with which a bar was sawed out of a window by Wilson and Robertson. The latter, a young and slim man, proposed that he exit first, enlarging the gap from the outside if necessary to allow his larger friend to follow. Wilson, however, insisted on going first, but found it impossible to get through the bars and jammed fast. Discovery followed and precautions were taken by the jailors to prevent any repetition. Robertson uttered not a word of reproach. Wilson, much moved by the fact that his obstinacy had prevented Robertson’s escape, was now bent on saving his friend’s life without further concern for his own.

Adjacent to the Tolbooth, or city jail of Edinburgh, is one of three churches into which the cathedral of St Giles is divided. It is called, from its vicinity, the Tolbooth Kirk. It was the custom that criminals under sentence of death were brought, with a sufficient guard, to this church for public worship on the Sabbath before their execution. It was supposed that their hearts would be moved by uniting their thoughts and voices for the last time with their fellow mortals, as all addressed their Creator. The congregation, it was also believed, could not but be impressed and affected to find their devotions mingling with those trembling on the verge of eternity. This practice, however edifying, was later discontinued – a consequence of the incident we are about to divulge.

The clergyman had concluded his sermon, part of which was directed at Wilson and Robertson, who were in the pew set apart for condemned persons, each secured betwixt two soldiers of the City Guard. The minister had reminded them that the next congregation they would join would be that of the Just or of the Unjust, and that their Psalms must be exchanged in two days for eternal Hallelujahs or Lamentations. They were also told to take comfort in their misery. While all who kneeled beside them lay under the same sentence of certain death, they alone had the advantage of knowing the precise moment at which it should be executed.

‘Therefore,’ urged the minister, his voice trembling with emotion, ‘redeem, my unhappy brethren, the time which is yet left; remember that through the Grace of Him to whom space and time are as nothing, Salvation may yet be assured, even in the brief delay which the Law affords you.’

Robertson was observed to weep at these words, but Wilson seemed as one who had not grasped their meaning and whose thoughts were elsewhere. The benediction was pronounced and the congregation was dismissed, many lingering to indulge their curiosity with a final look at the two criminals, now rising with their guards to depart. A murmur of compassion was heard among the spectators when all at once Wilson, a very strong man, seized two of the soldiers, one with each fist, calling to his companion,

‘Run Geordie,run!’

Wilson threw himself on a third guard and fastened his teeth on the collar of his coat. Robertson stood for a second as if thunderstruck, but at the cry of ‘Run, run!’ being echoed from many around, he shook off the remaining soldier, threw himself over the pews, scattered the dispersing congregation – none of whom felt inclined to stop a man taking his last chance for life – gained the door of the church and was lost to pursuit.

The generous bravery of Wilson heightened the feelings of compassion among the public, who also rejoiced in Robertson’s escape. This general feeling started a rumour that Wilson would be rescued from the place of execution, either by the mob, by his old associates, or by another act of strength and courage on his own part. The Magistrates, alarmed, thought it their duty to guard against any such disturbance and ordered out the greater part of the City Guard.

Its commander was Captain John Porteous.

-----------

1 ‘Jamie the Saxt’ here refers to Fife’s impoverished interior, contrasting it with its coastal seaports and golf links, the former being a rich source of ‘gowd’ to the treasury of His Majesty.

chapter three

And thou, great god of Aquavitae!

Wha sways the empire of this city

(When fou we’re sometimes capernoity),

Be thou prepared

To save us frae that black banditti,

The City Guard!

Robert Fergusson,The Daft Days

Captain John Porteous, a name memorable in the folklore of Edinburgh, as well as in the records of criminal jurisprudence, was the son of an Edinburgh tailor. His father wished him to follow this trade, but the youth had a wild propensity to dissipation which led him to The Scotch Dutch, an infantry corps long in the service of the States of Holland. Here he learned military discipline. Returning to his native city in the course of an idle and wandering life, his services were obtained by the magistrates of Edinburgh in the disturbed year of 1715 for disciplining their City Guard, in which he received a Captain’s commission.1It was only by his military skill and his alert and resolute character as an officer of the police that he merited the position, for he was a man of profligate habits and a brutal husband. However, his harsh and fierce activity rendered him formidable to rioters and disturbers of the public peace.

The corps in which he held his command was a body of about one hundred and twenty soldiers divided into three Companies and regularly armed, clothed and embodied. They had the charge of preserving public order and were chiefly military veterans who had the benefit of working at their trades when off-duty. Acting as an armed police force, they repressed riots and street robberies. They also attended all public occasions where popular disturbance might be expected.

The Lord Provost of Edinburgh was,ex-officio, commander and Colonel of the corps, which might be increased to three hundred men when the times required it. No drum but theirs was allowed to sound on the High Street between the Luckenbooths and the Netherbow. The escapades of the celebrated poet Robert Fergusson sometimes led him into unpleasantrencontreswith these conservators of public order. Indeed, he mentions them so often in his works that he may be termed their poet laureate.2He thus admonishes his readers, based doubtless on his own experience:

Gude folk, as ye come frae the fair,

Bide yont frae this black squad:

There’s nae sic savages elsewhere

Allowed to wear cockad.

The soldiers of the City Guard were for the greater part Highlanders. Neither by birth nor education were they trained to endure the insults of the rabble, the truant schoolboys, or the idlers with whom they came into contact. The tempers of the old fellows were soured by the indignities which the mob heaped on them on many occasions and frequently might have required the soothing strains of the poet:

O soldiers! For your ain dear sakes,

For Scotland’s love, the Land o’ Cakes,

Gie not her bairns sic deadly paiks,[blows]

Nor be sae rude,

Wi’ firelock or Lochaber axe,

As spill their bluid!

On all occasions when a civic holiday encouraged riot and disorder, a skirmish with these veterans was a favourite recreation of the rabble of Edinburgh. Though the City Guard is now extinct there may still be seen, here and there, the spectre of an old grey-headed and bearded Highlander. His war-worn features appear below an old fashioned cocked-hat, bound with white tape instead of silver lace. His coat, waistcoat and breeches are of a muddy red and, though bent with age, he bears in a withered hand an ancient weapon. This is a Lochaber axe; a long pole with an axe at the extremity and a hook at the back of the hatchet.3

Such a phantom of former days still creeps round the statue of Charles II in Parliament Square, and one or two others are supposed to glide around the door of their Guardhouse in the Luckenbooths, when their ancient refuge in the High Street was demolished. Their last march to do duty at Hallowfair4was most moving. On this joyous occasion, their fifes and drums had been wont to play the lively tuneJockey to the Fair, but on his final occasion the veterans moved slowly to the dirge of:the last time I cam’ ower the muir.5

This old Town Guard of Edinburgh with their grim and valiant corporal, John Dhu – the fiercest-looking fellow I ever saw – were in my boyhood the alternate to the terror and derision of the petulant brood of the High School. Kay’s caricatures6have preserved the features of some of these warriors. In the preceding generation, when there was perpetual alarm over Jacobite activities and plots, pains were taken by the magistrates of Edinburgh to keep the City Guard in an effective state, but latterly their most dangerous service was to skirmish with the rabble on the King’s birthday.7

To Captain John Porteous, the honour of his Corps was a matter of high interest and personal importance. He was incensed with Wilson over the affront to his soldiers in liberating his companion. He was no less indignant at rumours of a rescue of Wilson from the gallows, and uttered threats which would later be recalled to his disadvantage. Porteous, despite his readiness to come to blows with the rabble, was entrusted by the Magistrates with the command of the soldiers at Wilson’s execution. He was ordered to guard the gallows and scaffold with all the disposable force that could be spared for that duty – about eighty men.

The Magistrates took a farther precaution which deeply affected Porteous’s pride; they requested the assistance of part of a regular infantry Regiment. The soldiers were not to attend the execution itself, but were to be drawn up on the High Street, the principal street of the City, as a display of force to intimidate the multitude. Captain Porteous deeply resented the introduction of these Welsh Fusiliers into the city, and their parading on a street where no beating drums but his own might be allowed. As he could not vent his ill-humour on the Magistrates, it increased his indignation at Wilson and all who supported him. This combination of jealousy and rage wrought a change in the man’s countenance and bearing, visible to all who saw him on the day when Wilson was to hang.

Porteous was about the middle size, strong and well made, with a military air. His complexion was brown, his face somewhat fretted with the scars of the smallpox, his eyes more languid than keen or fierce. On the present occasion, however, it seemed as if he were agitated by some evil demon. His step was irregular, his voice hollow, his countenance pale and his eyes staring. His speech was confused, indeed his whole appearance so disordered that many remarked he seemed to befey, the state of those driven to their impending fate by an irresistible impulse.

One part of his conduct was particularly diabolical. When Wilson was delivered to him by the keeper of the Tolbooth to be conducted to the Grassmarket, Porteous, not satisfied with the usual precautions to prevent escape, ordered him to be manacled. This was justifiable, given his character and bodily strength, as well as from the fear of a rescue attempt. But the handcuffs being too small for the wrists of a man as big-boned as Wilson, were forced closed to the exquisite torture of the criminal. Wilson remonstrated against such barbarous usage, declaring that the pain distracted his thoughts from the meditation proper to his unhappy condition.

‘Your pain,’ replied Porteous, ‘will soon be at an end.’

‘And your cruelty is great,’ retorted Wilson, ‘You know not how soonyoumay be asking for mercy. God forgive you!’

These words, long afterwards remembered and quoted, were all that passed between Porteous and his prisoner. However, as they became generally known, they greatly increased the popular compassion for Wilson and the indignation against Porteous.

When the grim procession was completed, Wilson and his escort arrived at the scaffold in the Grassmarket. There appeared no sign of any attempt to rescue him. The multitude looked on with deeper interest than at ordinary executions; on the countenances of many was the stern, indignant expression with which the Cameronians had witnessed the execution of their brethren on that very spot.8But there was no attempt at violence. Wilson himself seemed disposed to hasten over the space that divided time from eternity. The devotions, proper and usual on such occasions, were no sooner finished than he submitted to his fate. The sentence of the Law was executed.

When he had hung on the gibbet long enough to be totally deprived of life, a tumult arose among the multitude. Stones were thrown at Porteous and his guards. The mob continued to press forward with howls and threats. A young fellow in a sailor’s cap sprang onto the scaffold and cut the rope by which Wilson’s body was suspended. Others approached either to carry it off for burial, or perhaps to attempt resuscitation.

This appearance of insurrection against his authority sent Captain Porteous into a rage. He forgot that since the sentence had now been executed, it was his duty not to engage in hostilities with the mob, but to withdraw his men. Instead, he sprang from the scaffold and snatched a musket from one of his soldiers. Commanding his men to open fire, he set them an example by firing his weapon and shooting a man dead on the spot. Several soldiers obeyed his command; six or seven persons were killed and a great many more wounded.

The Captain then proceeded to withdraw his men towards their Guardhouse in the High Street, but the mob were not so much intimidated as incensed by what he had done. They pursued the soldiers with curses and volleys of stones. As they pressed on towards them, the rearmost soldiers turned and opened fire, again with fatal results. It is not known for certain whether Porteous ordered this second fusillade, but the odium of that whole fatal day attached to him and to him alone. Arriving at the Guardhouse, he dismissed his men and went to make his report to the Magistrates.

Apparently by this time Captain Porteous had begun to doubt the propriety of his own conduct, and the reception he met with from the Magistrates made him still more anxious to gloss it over. He denied that he had given orders to fire; he denied he himself had fired; he even produced thefusee9which he carried as an Officer, for examination. It was found to be still loaded. Of three cartridges which he was seen putting into his pouch that morning, two were still there; a white handkerchief was thrust into the muzzle of the weapon and emerged unsoiled or blackened. To the defences based on these circumstances, however, it was pointed out that Porteous had not used hisownweapon, but had been seen to take one from a soldier.

Among the many killed and wounded by the firing were several individuals of higher rank, observing the scene from upper windows. The common humanity of the soldiers had made them fire over the heads of the crowd, this proving fatal to several of those persons. The voice of public indignation was loud, and before tempers had time to cool, the trial of Captain Porteous for murder took place before the High Court of Justiciary.

After a long hearing, the jury had the difficult duty of balancing the evidence of witnesses. Many respectable persons testified to the prisoner commanding his soldiers to fire, and himself firing hisfusée. Others swore that they saw the smoke and the flash and a man drop. On the other hand, testimony came from others who, though well-stationed, neither heard Porteous give orders to fire, nor saw him fire himself. On the contrary, they averred that the first shot had been fired by a soldier close by him. A great part of his defence was also founded on the turbulence of the crowd, which again witnesses represented differently. Some described a formidable riot, others the trifling disturbance usual on such occasions when the executioner and the men commissioned to protect him were routinely exposed to indignities.

Having considered their verdict, the jury found that that John Porteous fired a gun into the people assembled at the execution, and also that he gave orders to his soldiers to fire, resulting in many persons being killed or wounded. They also found that the Captain and his guards had been assaulted and wounded by stones thrown at them by the multitude.

The Lords of Justiciary passed sentence of death against Captain John Porteous. He was ordered to be hanged on a gibbet at the common place of execution on Wednesday, 8 September 1736. Furthermore, according to Scottish Law in cases of willful murder, all his movable property was forfeited to the King.10

-----------

1 The first major Jacobite rising and the inconclusive, ie drawn, Battle of Sheriffmuir, where the rebels, led by the Earl of Mar, faced a Government army under John Campbell, 2nd Duke of Argyll, of whomvide infra. The battle was wittily summarised by Anon: ‘Some say thatwewan, and some say thattheywan, while some say thatnanewan at a’, man; butweran, andtheyran andwe… ach we a’ ran awa’ man!’.

2 Robert Fergusson (1750–1774): Scottish poet and inspiration to Burns.

3 This hook was to enable the bearer of the Lochaber axe to scale a gateway by grappling the top of the door and swinging himself up by the staff of his weapon. Scott.

4 A market held on Hallowmas, or All Saints Day (1 November) at Edinburgh where it was the occasion of a large cattle-market.

5 A song by Allan Ramsay (1686–1758).

6 See John Kay,A Series of Original Portraits, With Biographical Sketches and Illustrative Anecdotes(Edinburgh: A & C Black, 1877).

7 Of King George III: June 4th.

8 The Cameronian sect of Presbyterians were the strictest among the Scottish Covenanters. Founded by Richard Cameron (1648–1680), they fiercely opposed any alliance of Church and State. Cameron was killed in action at the skirmish of Aird’s Moss. The closest present day sect are the Free Presbyterians who, impressively, regard the Free Church of Scotland (the ‘Wee Frees’) as dangerous libertines.

9 A flintlock rifle.

10 The five signatures affixed to the death warrant of Captain Porteous were headed by Andrew Fletcher of Milton, the Lord Justice Clerk. It was dated 20 July 1736.

chapter four

‘The Hour’s come, but not the Man.’1

On the day when Porteous was to suffer execution, the Grassmarket, extensive as it is, was crowded almost to suffocation. Spectators filled the windows of all the lofty tenements around it, and lined the steep, curving street called The Bow, by which the procession was to descend from the High Street. The antique appearance of the houses of The Grassmarket, some formerly the property of the Knights Templars and the Knights of St John, and which still exhibit on their fronts and gables the Cross of these Orders, gave additional effect to the scene. The Grassmarket itself resembled a huge dark sea of human heads, in the centre of which arose the fatal tree; tall, black, ominous – and from which dangled the deadly halter.

Amid so numerous an assembly there was scarcely a word spoken, save in whispers. The thirst for vengeance was allayed by its certainty and the populace suppressed all exultation, preparing instead to observe the scene of retaliation in silent, stern triumph. It was as if the very depth of the popular hatred of Porteous scorned to display itself. Indeed, a stranger might have supposed that so vast a multitude were assembled for some purpose arousing deepest sorrow and which had stilled the noise normally arising from such a concourse. If, however, he had gazed upon their faces, he would have been instantly undeceived. The compressed lip and the stern and flashing eye of almost everyone conveyed the expression of men now in full sight of triumphal revenge.

The usual hour for producing the condemned had been past for many minutes, yet the spectators observed no symptom of his appearance.

‘Would theydaredeny public justice?’ men began anxiously to ask each other. The first answer was bold and positive:

‘No.Theydarenot!’ But when the point was further canvassed, other opinions were entertained and various causes of doubt emerged. Porteous had been the favourite Officer of the Magistracy of the city; he had been described by his Counsel as the person upon whom the Magistrates relied in emergencies of unusual difficulty; and it had been argued that his conduct at Wilson’s execution was due simply to an excess of zeal in the execution of his lawful duty.

The mob of Edinburgh, when thoroughly excited, had always been one of the fiercest in Europe and of late had risen repeatedly against the authorities, sometimes with temporary success. They were conscious that they were no favourites with their rulers, and that for Captain Porteous’ violence to attract capital punishment would render it dangerous for Officers to effectively repress tumults. There is also the natural desire among governments for the maintenance of authority; and hence what had appeared to be an unprovoked massacre might be viewed otherwise in London by the Cabinet at St James’s. There it might be supposed that Porteous was exercising a trust delegated to him by the lawful civil authority. He had been assaulted by the populace, and several of his men hurt; and that in repelling force by force, his conduct could be fairly imputed to self-defence in the execution of his duty.

These powerful considerations induced the spectators to suspect the possibility of a reprieve; and to the causes which might influence their rulers in Porteous’ favour, the lower element of the rabble added another. It was said that Porteous repressed the slightest excesses of the poor with severity, while overlooking the license and pranks of the young nobles and gentry. This suspicion impressed the populace and was reinforced when word went round that certain citizens of higher rank had petitioned the Crown for mercy to Porteous.

While these arguments were being canvassed around, the expectant silence of the people changed into that deep, agitated murmur sent up by the ocean before the tempest begins to howl. The crowded populace, their motions corresponding to the unsettled state of their minds, fluctuated to and fro. That which the Magistrates had hesitated to communicate to them was at length announced. It spread like lightning among the spectators.

A reprieve from the Secretary of State’s office under the hand of his Grace the Duke of Newcastle had arrived, intimating the pleasure of Queen Caroline, Regent of the kingdom in the absence of King George II in Germany, that:

The execution of the death sentence pronounced against John Porteous, late Captain of the City Guard of Edinburgh and prisoner in the Tolbooth of that city, be respited for six weeks from the time appointed.

The assembled spectators uttered a roar of indignation and frustrated revenge, foretelling an immediate explosion of popular resentment. Such had actually been expected by the Magistrates, who had taken measures to repress it. But the shout was not repeated, nor did a riot ensue. The populace seemed ashamed of having expressed their disappointment in a vain clamour and the sound changed, not into silence, but into stifled mutterings. These each group maintained among themselves, and they blended into one deep and hoarse murmur floating above the assembly.Yet still, though all expectation of the execution was gone, the mob remained assembled and stationary, gazing on the preparations for death which had now been made in vain.

‘This man, Wilson,’ they said to each other, ‘this brave man was executed for stealing a purse of gold, while he who shed the blood of twenty of his fellow citizens, is deemed a fitting object for the exercise of the Royal prerogative of Mercy. Is this to be borne? Would our fathers have borne it? Are not we too, Burghers of Edinburgh – andScotsmen?’

The Officers of Justice began now to remove the scaffold, hoping that doing so would accelerate the dispersal of the crowd. The measure had the desired effect. The fatal tree was unfixed from the large stone pedestal or socket in which it was secured, and lowered slowly down upon the wain2for removal to its hiding place. Thereupon the populace, after giving vent to their feelings with a second shout of rage, began slowly to disperse.

In like manner, the windows were gradually deserted and groups of burgesses formed up as if waiting to return home when the streets should be cleared. In this case, all ranks regarded the cause as common to all. As noted, it was by no means amongst the lowest class, those most likely to riot at Wilson’s execution, that the fatal fire of Porteous’ soldiers had taken effect. Thus the Burghers, ever tenacious of their rights as the citizens of Edinburgh, were equally exasperated at the respite of Captain Porteous.

It was noticed at the time, and afterwards particularly remembered, that while the crowd was dispersing, several individuals were seen passing from one group of people to another, whispering to those protesting most violently against the reprieve. These were men from the country, generally supposed to be old friends and confederates of Wilson – and of course highly excited against Porteous.

If it was the intention of these men to stir the multitude to any immediate act of mutiny, it seemed for the time to be fruitless. The rabble, as well as the more respectable part of the assembly, dispersed and went home. It was only by observing the moody discontent or catching the conversation they held with each other that the mind of the citizenry could be gauged. One group was slowly ascending the steep incline of the West Bow to return to their homes in the Lawnmarket.

‘An unco thing is this, Mrs. Howden,’ said Peter Plumdamas to his neighbour, a rouping-wife, or saleswoman, offering his arm to assist her in the ascent, ‘to see the grit folk at Lunnon set their face against Law and Gospel and let loose sic areprobateas Porteous upon a peaceable town!’

‘And think o’ the weary walk they hae gien us,’ answered Mrs Howden, ‘and sic a comfortable window as I had gotten, too, just within a penny-cast of the scaffold. I could hae heard every word the minister said. I paid twalpennies for my stand, and a’ for naething!’3

‘I judge,’ said Plumdamas, ‘that this reprieve wadna stand gude in the auld Scots Law when Scotland was a Kingdom.’

‘I dinna ken about the law,’ answered Mrs Howden; ‘but I ken this; when we had a King, and a Chancellor, and a Parliament o’ our ain, we could aye peeble them wi’ stanes when they werena gude bairns; but naebody can reach the length o’ Lunnon.’

‘Weary on Lunnon, and a’ that ever came out o’t!’ said Miss Grizel Damahoy, an old seamstress. ‘They hae taen away our Parliament and oppressed our trade. Our gentlefolk will hardly allow that a Scots needle can sew ruffles on a sark, or lace on an owerlay.’4

‘And now,’ responded Plumdamas, ‘sic a host of idle English excisemen torment us, that an honest man canna fetch sae muckle as an anker5o’ brandy frae Leith to the Lawnmarket, but he’s like to be robbit o’ the very gudes he’s bought and paid for. I winna justify Andrew Wilson for taking what wasna his; but if he took nae mair than his ain, there’s an awfu’ difference between that and the fact this man stands for.’

‘If ye speak about the Law,’ said Mrs Howden, ‘here comes Mr Saddletree, that can settle it as weel as ony Judge.’

The party she mentioned was a grave elderly person with a superb periwig, dressed in a decent suit of sad-coloured clothes. He came up as she spoke and courteously gave his arm to Miss Grizel Damahoy. Mr Bartoline Saddletree kept a highly esteemed shop for harness, saddles &c. at the sign of the Golden Nag, at the head of Bess Wynd.6His genius, however, as he himself and most of his neighbours agreed, lay towards matters of the Law. He was in frequent attendance at the pleadings and arguments of lawyers and judges in Parliament Square, where he was more often to be found than at his own business. However, his active wife both pleased the customers and scolded the journeymen. This good lady let her husband go his own way, improving his stock of legal knowledge, while she controlled the domestic and commercial departments.

Bartoline Saddletree had a considerable gift of words, which he mistook for eloquence and conferred liberally upon society. There was a saying that he had a Golden Nag at his door and a Grey Mare, his wife, in his shop. This was lucky for him, since his fortune increased with little trouble on his part and little interruption of his beloved legal studies.

Saddletree laid down, with great precision, the law upon Porteous’s case. His conclusion was that if Porteous had fired five minutes sooner, that is,beforeWilson was cut down, he would have beenversans in licito; that is, engaged with discretion in a lawful act and only guilty of excessive zeal, which might have mitigated the punishment.

‘Discretion!’ echoed Mrs Howden, on whom the finesse of this distinction was wasted, ‘whan had Jock Porteous either discretionorgude manners?’

‘Mrs Howden, Miss Damahoy,’ implored the orator, ‘mind the distinction. Now, with the body of the criminal cut down, and the execution ended, Porteous was no longerofficial; the act which he had come to protect and guard being ended, he was no better thancuivis ex populo.’7

‘Quivis, Mr Saddletree, craving your pardon, with the accent on thefirstsyllable,’ said Reuben Butler, an assistant schoolmaster of a parish near Edinburgh, who came up behind them just as the false Latin was uttered.

‘What means this interruption, Mr Butler? But I am glad to see ye, notwithstanding. I speak as did Counsellor Crossmyloof, and he said “cuivis”.’8

‘If Crossmyloof used the dative instead of the nominative case, I would have crossed his palm with a leather strap, Mr Saddletree. That was a grammatical solecism.’

‘I speak Latin like a lawyer, Mr Butler, and not like a schoolmaster. All I mean to say is that Porteous merits execution because he did not fire when he was in office, but waited till the body was cut down. He himself thusexonered9the public trust imposed on him.’

‘But, Mr Saddletree,’ said Plumdamas, ‘do ye really think John Porteous’s case wad hae been better if he had begun firingbeforeony stanes were flung?’

‘Indeed I do, Plumdamas,’ replied Bartoline, confidently, ‘he being then in point of trust and power, the execution being butinchoat, or underway, but not finally ended. But after Wilson was cut down he should hae gotten awa’ fast wi’ his Guards up the West Bow.’

‘I’ll tell ye what it is, neighbours,’ said Mrs Howden, ‘I’ll ne’er believe Scotland is still Scotland if we Scots accept the affront they hae gien us this day. My daughter’s wean, little Eppie, played truant frae the school and had just cruppen10to the gallows’ foot to see the hanging, as is natural for a wean. She might hae been shot wi’ the rest o’ them!’

‘Weel,’ said Mrs Howden, ‘the sum o’ the matter is this; were I a man, I wad hae revenge on Jock Porteous, whatever the upshot.’

‘I would claw down the Tolbooth door wi’ mynailsto be at him!’ said Miss Grizel.

‘Ye may be right, ladies,’ said Butler, ‘but I would not advise you to speak so loud.’

‘Speak?’ exclaimed both ladies, ‘there will be naething else spoken about frae the Weighhouse to the Watergate till this affair is either mended – or ended!’

The females now departed home. Plumdamas joined the other two gentlemen in drinking theirmeridian, their noonday bumper dram of brandy at their usual place of refreshment in the Lawnmarket. Mr Plumdamas then departed for his shop, while Reuben Butler walked down the Lawnmarket with Mr Saddletree, each talking whenever he could thrust a word in; the one on the Laws of Scotland, the other on those of Latin syntax; and neither listening to a word uttered by the other.

-----------

1 Walter Scott,The Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border(1802–1803). Notes toThe Water-Kelpieby the Rev. Dr John Jamieson, author ofAn Etymological Dictionary of the Scottish Language(1808).

2 A heavy, four-wheeled, horse-drawn agricultural wagon.

3 Twelve pennies: a shilling of which, until 1971, there were twenty in the Pound (ie 5p).

4 From Anglo-Saxonserc, a shirt or chemise. In Burns’sTam o’ Shanter, the ‘cutty’ (short) sark of the dancing witch Nannie discloses an impressive amount of flesh to the eponymous hero. An ‘owerlay’ was a cravat or neck-cloth.

5 A keg containing the equivalent of 8.5 imperial gallons.

6 An alley leading from Edinburgh’s Lawnmarket, at the site of the Tolbooth, to near the head of the Cowgate. It was removed in 1809 to make way for the new libraries of the Faculty of Advocates and the Writers to the Signet, Scott.

7 Literally ‘anyone among the people’.

8Cuivisis in fact correct. Butler’s, ie Scott’s, Latin grammar is at fault. Tut.

9 Deserted; annulled.

10 Crept.

chapter five

Elswhair he colde right weel lay down the law,

But in his house was meek as is a daw.

Attributed by Scott to ‘Sir Davie Lindsay’

Jock Driver the carrier has been here, speiring about his new graith,’1said Mrs Saddletree to her husband as he and Reuben Butler crossed his threshold. ‘And the laird of Girdingburst has had his running footman here, and then ca’d himsell, a civil young gentleman, to see when the broidered saddle cloth for his sorrel horse2will be ready, for he wants it for the Kelso races.’

‘Indeed?’

‘And his lordship, the Earl of Blazonbury, is clean daft that the harness for his six Flanders mares, wi’ the crests, coronets, housings, and mountings are no sent hame according to your promise given.’

‘Weel, weel, gudewife,’ said Saddletree, ‘if he gangs daft, we’ll hae him cognosced.3It’s a’ very weel.’

‘It’s weel that ye think sae, Mr Saddletree,’ she answered, nettled at his indifference to her reports; ‘mony a man wad hae been black-affronted if sae mony customers had ca’d and naebody to meet them but women-folk; for a’ the lads were aff as soon as your back was turned to see Porteous hanged.’

‘Mrs Saddletree,’ said Bartoline, with an air of consequence, ‘dinna deave me wi’ your nonsense; I was under the necessity of being elsewhere.Non omnia possumus… possimis? I ken our Law-Latin offends Mr Butler’s ears, but it means that naebody can do twa things at once, not even the Lord President himsell.’

‘Very right, Mr Saddletree,’ answered his wife with a sarcastic smile, ‘and it wad better become ye, since ye say ye hae skill o’ the Law, to see if ye can do onything for Effie Deans. The puir, puir thing is lying up in the Tolbooth yonder, cauld, hungry, and comfortless. She’sourservant lass, Mr Butler, an innocent lass to my thinking and usefu’ in the shop. She was aye civil, and a bonnier lass wasna in Auld Reekie. And when folk were hasty and unreasonable, she could serve them better than me, who’s a bit short in the temper. I miss Effie daily.’

‘I think,’ said Butler, after some hesitation, ‘I have seen this girl in the shop; a modest, fair-haired lass?’

‘Ay, ay, that’s puir Effie,’ said her mistress. ‘How she was abandoned, or whether she was innocent o’ the sinful deed, God in Heaven knows.’

Butler had suddenly become agitated and fidgeted up and down the shop. ‘Was not this girl,’ he said, ‘the daughter of David Deans that had the fields at St Leonard’s? And has she not a sister?’

‘She has; Jeanie Deans, ten years aulder than hersell. She was here a wee while ago, asking about her sister. And what could I say, except that she should come back and speak to Mr Saddletree? Not that I thought Mr Saddletree could do her muckle good or ill, but it wad serve to keep the puir thing’s heart up.’

‘Ye’re mistaken though, gudewife,’ said Saddletree. ‘I could hae gien her great satisfaction; I could hae proved to her that her sister was indicted upon the Statute of 1690, Chapter One:for the mair ready prevention of Child-murder; for concealing Pregnancy and giving no account of the Child borne.’

‘I trust to God,’ said Butler, ‘that she can clear herself.’

‘And sae do I, Mr Butler,’ replied Mrs Saddletree. ‘I am sure I wad hae helped her as if she were my ain daughter; but I had been ill a’ the summer, and scarce out of my room for twalve weeks. And as for Mr Saddletree, he might be in a lying-in hospital, and ne’er find out what the women cam there for. Sae I saw naething o’ her, or I wad hae had the truth out o’ her. But we think her sister maun be able to say something in Court to clear her.’

‘The haill Parliament House,’ said Saddletree, ‘was speaking o’ naething else, till this Porteous business put it out o’ mind. It’s a presumptive infanticide and there’s been nane like it since the case of Luckie Smith the howdie4that was hanged in the year 1679.’

‘Whatever’s thematterwi’ you, Mr Butler?’ said Mrs Saddletree, ‘ye’re gone as white as a sheet!’

‘I… walked here from Dumfries yesterday,’ said Butler, forcing himself to speak, ‘and this is a warm day…’

‘Sit down and rest,’ she said, ‘Ye’ll kill yoursell, man, at that rate. And are we to wish you joy o’ getting the Dumfries scule, Mr Butler, after teaching at it a’ the summer?’

‘No, Mrs Saddletree, I am not to have it.’

‘And so ye’re back to Liberton scule as the assistant, to wait for dead man’s shoon? Frail as Mr Whackbairn is, he may live as lang as you.’

‘Very likely,’ replied Butler, with a sigh. ‘I do not know if I should wish it otherwise.’

‘Nae doubt it’s vexing,’ continued the good lady, ‘to be in a dependent station; you that deserves muckle better. I wonder how yebearthese crosses.’

‘Quos diligit castigat,’5answered Butler; ‘even the pagan Seneca could see an advantage in affliction.’

He stopped and sighed.

‘I ken what ye mean,’ said Mrs Saddletree, looking toward her husband; ‘there’s whiles we lose patience in spite of baith book and Bible. But ye’ll stay and take some kale wi’ us?’

Mr Saddletree laid aside Balfour’sPractiques6to join in his wife’s hospitable suggestion. But the teacher declined all entreaties and took his leave.

‘I wonder,’ said Mrs Saddletree, looking after him as he walked up the street; ‘what makes Mr Butler sae distressed about Effie’s misfortune? There was nae acquaintance atween them that ever I heard of; but they were neighbours when her father David Deans was on the Laird o’ Dumbiedikes’ land. Mr Butler wad ken Davie or some o’ her folk… Get up, Mr Saddletree! Ye have sat yoursell on the very brecham7that wants stitching – and here’s Willie, the new prentice. Ye little Deil that ye are! What takes you raking through the gutters to see folk hangit? Gang in and tell Peggy to gie ye broth, for ye’ll be as gleg as a gled.8Ye mind he’s fatherless, Mr Saddletree?’

‘True, gudewife,’ said Saddletree, ‘we are inloco parentisand I hae thoughts of applying to the Court for a commission as factorloco tutoris,9seeing there is nae tutor nominate and the tutor-at-law declines to act.’

‘He was in rags when his mother died,’ said Mrs Saddletree, ‘and that blue polonie that Effie made for him out of my auld mantle was the first decent thing the bairn ever had on. Poor Effie! Can ye tell me now really, wi’ a’ your law, will her life be in danger when they canna prove that there ever was a bairn at all?’

‘Whoa,’ said Saddletree, delighted at finding his wife interested in a legal topic. ‘Whoa, there are two sorts ofmurdrumormurdragium, or what is popularly called murder. I mean there are many sorts; for there’s yourmurthrum per vigilias et insidias,10and yourmurthrumunder trust. However, the case of Effie, or Euphemia, Deans is one of those cases of murderpresumptive, that is, a murder of the law’s inferring, being derived from certainindiciaor grounds of suspicion.’

‘So,’ said the good woman, ‘unless poor Effie has revealed her pregnancy to others, she’ll be hanged, whether the bairn was stillborn, or alive at this moment?’

‘Assuredly,’ said Saddletree, ‘it being a statute to prevent the crime of bringing forth children in secret. The crime is rather a favourite of the Law,thisspecies of murder being one of its ain creation.’

‘Then, if the Lawmakesmurders,’ retorted Mrs Saddletree, ‘the law should be hanged for them; or if they wad hang alawyerinstead, the country wad find nae fault!’

-----------

1 Enquiring about his new harness.

2 Chestnut.

3 Examined to determine if a person is insane or mentally incompetent.

4 Midwife.

5 Butler quotes from the Latin Old Testament; Hebrews 12.6:quem enim diligit Dominus castigat, ‘the Lord punishes those He loves’. The notion also appears in Lucius Seneca’sAd Lucilium Epistulae Morales, Moral Letters to Lucilius; 66.11-13

6 A Dictionary of Scots Law published in 1774 and ascribed to Sir James Balfour of Pittendreich, President of the Court of Session 1567 – 1568.

7 The collar of a draught horse.

8 As sharp-eyed as aMilvus milvus– the Red Kite.

9 A person responsible for a minor’s education.

10 Latin. ‘By keeping watch and ambush’ ie premeditated murder.

chapter six

But up then raise all Edinburgh,

they all rose up by thousands three.

Johnnie Armstrang’s Goodnight.

Reuben Butler, on his departure from the sign of the Golden Nag, went in quest of a lawyer friend to make inquiries concerning Effie Deans. Everyone, however, was for the moment stark-staring mad on the subject of Porteous and engaged in attacking or defending the Government’s reprieve. Butler wandered about until dusk, resolving to visit Deans in the Tolbooth when his doing so might be least observed. He passed through the narrow, partly-covered passage leading to the north-west end of the Parliament Square. He now stood before the Gothic entrance of the ancient prison, which reared up in the middle of Edinburgh’s High Street, forming the termination to a huge pile of buildings called the Luckenbooths.1

These, for some inconceivable reason, our ancestors had jammed into the middle of the principal street of the City, leaving only a narrow street on the north side for passage. To the south, the side into which the prison opens, was a narrow crooked lane winding betwixt the high, sombre walls of the Tolbooth on the one side and the buttresses of the old St Giles Cathedral upon the other. To give some gaiety to this sombre passage, known as the Krames, were a number of little booths, or shops. Here were hosiers, glovers, hatters, milliners, indeed all who dealt in haberdashery.

Butler found the outer turnkey, a tall, thin old man with long silver hair in the act of locking the outer door of the jail. He asked admittance to Effie Deans, confined upon accusation of child-murder. The turnkey, civilly touching his hat out of respect to Butler’s black coat and clerical appearance, replied that it was impossible at present.

‘You shut up earlier than usual on account of Captain Porteous’s affair?’ asked Butler.

The turnkey gave two grave nods and, withdrawing a ponderous key of about two feet in length,2he proceeded to shut a strong plate of steel which folded down above the keyhole, and was secured by a steel spring and catch. Butler stood still instinctively while the door was made fast. Then, looking at his watch, walked briskly up the street, muttering to himself:

Porta adversa, ingens, solidoque adamante columnae;

Vis ut nulla virum, non ipsi exscindere ferro

Coelicolae valeant.3

Having wasted half an hour more in a fruitless attempt to find his legal friend, he left the city for his residence in the small village of Liberton, two miles south of Edinburgh. The metropolis was at this time surrounded by a high wall with battlements and flanking projections at intervals. Access was through gates called in Scotsports, which were shut at night. A small fee to the Waiters, or keepers, would procure egress and ingress at any time through a wicket in the large gate. As the hour of shutting the gates was close, he made for the nearest, the West Port, which leads out of the Grassmarket. He reached it in time to pass through the city walls and entered the suburb of Portsburgh, chiefly inhabited by the lower order of citizens and mechanics. Here he was unexpectedly interrupted.

He had not gone far from the gate before he heard the sound of a drum and, to his great surprise, met an advancing crowd occupying the whole front of the street, with a considerable mass behind. They were moving with speed towards the gate he had just passed through, having in front of them a drum beating to arms. While he considered how to escape, they came full on and stopped him.

‘Are you a clergyman?’ he was asked. Butler replied that he was in holy orders, but was not a placed minister.

‘It’s Mr Butler from Liberton,’ said a voice from behind, ‘he’ll do the duty as weel as ony man.’

‘You must turn back with us, sir,’ said the first speaker, in a civil but peremptory tone.

‘For what purpose, gentlemen?’ said Butler. ‘I live some distance from town.’

‘You shall be sent safely home; no man shall touch a hair of your head; but you must, and shall, come with us.’

‘But to whatpurpose?’ said Butler.

‘You shall know that in good time. I warn you, look neither to the right nor the left and take no notice of any man’s face.’

He was compelled to turn round and march in front of the rioters, two men supporting and partly holding him. During this parley the insurgents had made themselves masters of the West Port by rushing upon the Waiters and taking the keys. They bolted and barred the folding doors and closed the wicket. Seemingly prepared for every emergency, they then called for torches. By the light of these, they secured the wicket with long nails brought for that purpose.

While this was going on, Butler watched the individuals who led this singular mob. The torch-light showed those who seemed most active to be dressed in sailors’ jackets, trousers, and sea-caps; others were in large, loose-bodied greatcoats and slouch hats. There were also several in women’s dress but whose deep voices, masculine deportment and mode of walking gave another interpretation. They moved by a well-concerted plan of arrangement and had signals and nicknames by which they distinguished each other. Butler heard the name ‘Wildfire’, to which one Amazon seemed to reply.

The rioters left a small party to observe the West Port and told the Waiters, if they valued their lives, to remain in their lodge and make no attempt to repossess the gate. They then moved rapidly along the Cowgate, the mob of the city everywhere rising at the sound of their drum and joining them.

Arriving at the Cowgate Port, they secured it with as little opposition as the former gate, made it fast, and left a small party to guard it. The mob, at first only about one hundred strong, now amounted to several thousand and was constantly increasing. They divided to ascend the various narrow lanes which lead up from the Cowgate to the High Street, beating to arms as they went and calling on all true Scotsmen to join them. They now filled the principal street of the city.

The Netherbow Port might be called the Temple Bar of Edinburgh. Placed across the High Street at its eastern termination, this gate divided Edinburgh from the suburb of the Canongate, just as Temple Bar separates London from Westminster. It was of the utmost importance to the rioters to possess the Netherbow because quartered outside in the Canongate was a regiment of infantry. Commanded by Colonel Moyle, it might have occupied the city by advancing through this gate and thus defeat their purpose. The Netherbow Port was secured with as little trouble as the other gates, a strong party being left to watch it.

The next object of the insurgents was to disarm the City Guard and procure arms for themselves; for scarce any weapons but staves and bludgeons had been yet seen among them. The Guardhouse was then a long, low, ugly building like a long black snail crawling up the middle of the High Street. The insurrection was so unexpected that there were no more than the ordinary Sergeant’s Guard of the city corps on duty and even these were without powder and ball. There was a sentinel on guard, the one town-guard soldier to do his duty on that eventful evening. He levelled his musket and ordered the foremost of the rioters to stand off. The young Amazon, whom Butler had observed to be particularly active, sprang upon the soldier, seized his musket, wrenched it from him and threw him down on the causeway. One or two soldiers who turned out to support their sentinel were also seized and disarmed. The mob then occupied the Guardhouse, disarming and then dismissing the rest of the men on duty. It was later noted that although these very city-soldiers had effected the slaughter which the riot was designed to revenge, no harm was offered to them. It was as if the vengeance of the people disdained any head other than that which they regarded as the source of their injuries.

On taking the Guardhouse, the first act of the multitude was to destroy the drums, by which an Alarm might have been conveyed to the garrison in the Castle. For the same reason they now silenced their own drum, beaten by a son of the drummer of Portsburgh, whom they had forced into service. Their next business was to distribute to the boldest of the rioters the guards’ guns, bayonets, partisans, halberds, and Lochaber axes. Until this point the rioters had kept silence on the ultimate object of their rising. All knew it, but none expressed it. Now, however, they raised a tremendous shout of, ‘Porteous.Porteous! To the Tolbooth!’