4,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The Lilliput Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

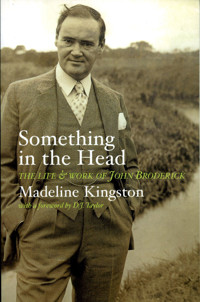

This is the first full biography of Athlone-born writer John Broderick (1924-89), whose powerful Balzacian novels of life in the Irish midlands depict sexuality and Catholicism in a series of pungent tableaux and portraits drawn from vivid but entrapped lives. Son of a prosperous baker, the solitude of his childhood (compounded by boarding-school), an enveloping mother, homosexuality and alcoholism fuelled his fictions, from The Pilgrimage (1961) to An Apology for Roses (1973) and The Trial of Father Dillingham (1982). Self-exiled to Bath in England with his housekeeper during the 1970s, he became an astringent commentator on the rapidly shifting mores of the Irish scene. A neglected but powerful writer, his work complements that of his rival Edna O'Brien and holds up a mirror to an Ireland of the mid-twentieth century like no other novelist of his day. His writings, now celebrated in annual John Broderick Weekends instituted by the Athlone Rotary Club in 1999, are of increasing relevance and interest, and introduce a new generation of readers to this skilled scourge of Irish society, for whom life was 'something in the head, and almost never in the body'. Two of his early novels, The Pilgrimage and The Waking of Willie Ryan, are being reissued by The Lilliput Press in tandem with this book.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

Something

in the Head

The life & work of John Broderick

Madeline Kingston

THE LILLIPUT PRESS

DUBLIN

Acknowledgments

I am indebted to many people for their help in my research for this book, and particularly to those in Athlone and elsewhere who knew John Broderick personally and willingly shared their memories with me. The original John Broderick Committee, chaired by George Eaton, brought the man and his work back into the public consciousness in 1999 and encouraged my initial interest. George Eaton supplied some invaluable material from his personal archives. Gearoid O’Brien, who will recognize much of his own work in the early pages of this biography, has been endlessly helpful, encouraging and inspiring throughout the last four years, and has devoted many hours to finding press references and to putting me in contact with people who had stories to tell. Gearoid has also been responsible for supplying the majority of the photographs in the book and conveying them to the publishers by arcane technological means.

Of those to whom I have spoken in Ireland, I particularly valued the help and the time of Mrs Pat Drummond (née Coughlan), Father Cathal Stanley, Archdeacon Patrick Lawrence, Mr Bert Heaton, Mrs Betty Claffey (née Hogan) and Mrs Maureen Doherty (née Hunt). Patrick Hunt sent several long and fascinating letters from his home in Toronto.

In London, Andrew Hewson opened up the files of the John Johnson Agency, shared his personal recollections of Broderick and continued to encourage me with his interest throughout the project. I had the good fortune to meet three of Broderick’s long-suffering editors: Agnes Rook, Ken Thomson and Ken Hollings, all of whom for all the suffering remember him as a friend; and to speak at length to Elena Salvoni, whose very best stories were all off the record.

Foreword

In May 1999 the Athlone Rotary Club staged a celebration to mark the tenth anniversary of John Broderick’s death. It was a convivial affair, spread over a weekend and involving a requiem mass, the naming of a street in Broderick’s memory, and a great deal to eat and drink. Pride of place in the assemblage of notables bidden to attend was occupied by ‘The Minister’, Mrs O’Rourke TD, and ‘Bishop John’ of the diocese of Clonfert, to whom, I noted with interest, elderly men still raised their hats when they passed on the pavement.

The highlight of this commemoration was dinner at a restaurant overlooking the lake. Speeches were called for, and given. When they were over a gentleman rose unheralded from one of the side-tables and declared that he, too, wished to say a few words. The few words went on for some time, rather to the annoyance of the senior Rotarian at my side, but then there was a revelation. ‘Not many of you will know’, the speaker announced, with the air of one who imparts an absolutely sensational fact, ‘that many years ago it was I who taught Bishop John to serve.’ At this there was a kind of miniature explosion from the back of the room and a male voice shouted, ‘Well, he went a bloody sight further in the Church than you did!’ It struck me that what I had witnessed, here in Athlone, with the midlands twilight slowly descending around us, was a scene from one of Broderick’s novels.

It would be presumptuous of me to claim that I knew John Broderick. I met him only once, at the very end of his life, and most of the assumptions I made about him on the strength of having read his novels I now find to be quite mistaken. If nothing else, Madeline Kingston’s excellent study is a corrective to the idea that you can ever wholly understand a writer through his or her books. Back in 1987, scrabbling for a toe-hold on the rock-face of London literary journalism, I was reviewing novels for the newly establishedIndependent. These were more spacious days for newspaper arts journalism, and the deputy literary editor, Robert Winder, had time to root around the new books and consider which of them might suit the tastes of his swarm of critics. And so there arrived on my desk, sometime in the early autumn, in its ghastly sapphire and grey jacket, a copy of Broderick’sThe Flood.

I had read nothing of Broderick’s work before – not quite the shocking dereliction it sounds, as his English reputation never approached that of contemporaries such as Edna O’Brien and John McGahern – butThe Floodseemed to me unlike any modern Irish novel I had ever come across: an individual blend of grim comedy, all done in glorious Athlone dialect, and secret grief built on a precise understanding of how the small-town midlands society of Broderick’s childhood worked.

Not long after the review appeared, there came an appreciative letter from an address in Bath. This was followed by a correspondence and finally an invitation to lunch in London, which took place on a stifling day in early summer at Simpson’s in the Strand. Damson-faced, solicitous beneath the winnowing fans, shuffling a little on a stick, Broderick looked like a man who was about to keel over with a stroke, which is exactly what he did a month or so later back in Bath. Phone calls made in the wake of this news were fielded by his legendary housekeeper Miss Scanlon. I never saw him again, and within a year he was dead. By chance a postcard from that era resurfaced the other day, in which Broderick showed an interest in William Trevor’s novel,The Silence in the Garden. Sixteen years later it seems a signal from another world: a landscape full of excitement over new books and their writers, and famous Irish novelists taking one to lunch at Simpson’s.

AsSomething in the Headmakes plain in spades, Broderick was an intensely solitary man: the gaze that he turned on the Ireland of his day almost entirely backward-looking, the opinions that he pronounced, whether on Church or State, deeply conservative. ‘How nice that John’s written a good Catholic book,’ the sisters of the Athlone convent were supposed to have remarked on hearing that Broderick’s first novel was calledThe Pilgrimage. Despite a prohibition notice from the Censorship Board, it turned out that this was the literal truth. The roles into which he was cast by his upbringing were, you feel, deeply uncongenial to him (the local businessmen who watched his attempts to behave in a manner befitting the notional proprietor of the town’s largest bakery laughed at what they called ‘all that eejiting about’) and fuelled the alcoholism that dominated his middle years. Going in search of him, in fact, one finds only a smokescreen of evasions and refusals to be drawn. Of his supposed homosexuality, or emotional career generally – and he was once quoted to the effect that ‘I did everything I wanted in every conceivable way’ – his biographer can only note ‘no evidence of any sustained relationship at any time of his life’. Most of his deepest feelings, as Madeline Kingston discreetly shows, were put into his work, and it is the sense of this warm, sharp and somehow self-enclosed sensibility – an intelligence staring out from behind a high wall, reluctant in the last resort to join the world that teems beyond it – that gives a novel such asThe Waking of Willie Ryanits distinction.

At the same time, it takes a visit to Athlone to establish what lies at the heart of Broderick’s work. Mid-twentieth-century Irish provincial life has no better elegist. The grim Angevin Castle, the great midland plain rolling out into the distance, the mutinous Shannon flowing on to the sea: all these are to Broderick what central Dublin was to Joyce. Put up by the Rotary Club at an Athlone hotel, I had a queer feeling on my first visit to the place that I had been there before. It turned out to have been the model for Mrs O’Flaherty Flynn’s establishment, the Duke of Clarence, inThe Flood.

A decade and a half after his death, with reissues of his books, this biography and the Athlone commemoration now a biennial event, his reputation has survived far better than many of his obituarists might have predicted. ‘I thought it was over, like a fool. It never is in Ireland,’ a character inThe Rose Treephilosophizes. No, it never is.

D.J. TAYLOR

It is not that I am really cold-hearted:

it is simply that life for me is something in the head,

and almost never in the body.

This is a great fault.

I.I bake buns

On a visit to Garbally College in the late 1960s John Broderick talked to some young teachers about their work and responsibilities. One of them was moved to ask in turn, ‘And what do you do?’ ‘Ah,’ said John, ‘What do I do? I bake buns.’

He did, up to a point, bake buns, and was the fourth generation of his family to do so. His great-grandfather Michael was a baker in Athlone from about 1840, and the eldest son, another Michael, took over a bakery in Connaught Street in 1891. It was a period when independent bakeries flourished in towns like Athlone and competition was fierce. Michael’s brothers, Francis and Edward, were employed by Newton’s, one of the larger rival firms, and all three were involved in legal proceedings. Michael’s bake-house was burnt down after a public protest about his continuing the practice of night-work for his employees when other bakeries had abandoned it. He was awarded £75 damages by the court. A few months later his brother Francis was sentenced to a month’s hard labour in Tullamore Gaol following a brawl in which a baker from another firm was wounded. Rather than serve the sentence, he fled to America, but became ill in the course of his journey and died a few days after his arrival, in the care of the Sisters of the Congregation of St Joseph. The third brother, Edward, took an action against three others in the bakery trade for insults and death-threats; the three were bound over to keep the peace.

In 1904 Michael went bankrupt. In a wonderfully Irish solution to the problem, he then went off to seek his fortune in America, while his wife Bridget, formerly Bridget Galvin of Clonown, took over what remained of the business and turned it into a profitable concern. Gearoid O’Brien, also a native of Connaught Street and later librarian in Athlone Public Library, refers to Bridget as ‘one of the great women of Connaught Street’, a group of women who took the places of their lost, failed or strayed husbands and created success out of the initial necessity to support themselves and their families. Her grandson’s last two novels, set in a barely disguised Athlone of the 1930s, are filled with women of character, the sort of women who keep the world turning because they know there is no alternative.

Bridget’s son John married Mary Kathleen (Mary Kate) Golden from Boyle in 1922, and took over the running of the bakery from his mother. He built it into a major business, supplying towns all over the midlands and west from the base in Connaught Street. John and Mary Kate lived at 5 Connaught Street and their son John Junior was born there in 1924. A previous child, Bernard, had died in infancy, and the safe arrival of John must have given his parents a particular joy. But that joy came to an untimely end three years later in 1927, when John Senior died suddenly, leaving Mary Kate a widow after only five years of marriage, aged twenty-nine and with a three-year-old son. They were to live together until her death in 1974.

John Broderick later recalled his childhood as having been a happy one, but also solitary. His world was Connaught Street, a street of independent small businesses, of which Broderick’s Bakery was the most prosperous. Connaught Street is, self-evidently, on the Connaught side of the river Shannon which, at that point, marks the boundary of the ancient provinces of Connaught and Leinster. Young John’s first educational experience, with the Sisters of Mercy at St Peter’s Infants’ School, was positive: the nuns were immensely kind, he never forgot Sister Margaret Mary in particular, and ‘while they didn’t teach us much except our prayers, and how to count our beads, we had a great time’. It was a gentle start to schooling for a very sheltered only child.

At the age of seven he moved on to the National School, the Dean Kelly Memorial, and found it very different – ‘that was the first blow I got in my life’ – when he found himself for the first time mixing with boys of all sorts, some of whom ‘were determined to make you as tough as they thought they were’. He would have been in any case set apart from his contemporaries by his home situation, and the division was further exacerbated by the fact that his family had money. A school friend of the time tells of John being sought out by other boys because only he had a real leather football, and then being left to stand on the sidelines while they played. There are echoes of that sad little story throughout John Broderick’s life, and they do not relate only to material possessions.

He began his secondary education at the Marist Brothers’ School, which as he said later took him across the bridge and into a part of Athlone that he knew only slightly, but he had spent less than a year there when the second blow of his life came – a double blow. In 1936 his mother remarried, and at the same time John was sent away to school.

Mrs Broderick married Paddy Flynn, the manager of her bakery. She was a beautiful 38-year-old woman of some social pretension, not at all in the mould of her mother-in-law, Bridget Galvin. Flynn was a handsome rogue and womanizer, devoted to the business then and thereafter but not likely to slip easily into the role of husband and stepfather. John, who from the age of three had spent almost all his time with his mother, and who had little memory of his father, was now at the age of twelve confronted with her remarriage and with separation from her. It was not unusual at that time for children like him to be sent to boarding-school, but he had already started his secondary schooling, and might have expected to continue it, with the Marist Brothers.

In the event he went first to Summerhill College in Sligo, the diocesan school of Elphin. He had little to say about it in later years except that he found the regime harsh, and he claimed to have been expelled for raiding the kitchen. In January 1938 he was enrolled at St Joseph’s College in Garbally, just outside Ballinasloe, and remained there until the end of his formal schooling.

St Joseph’s proved to be a happier place. It was the diocesan college of Tuam, housed in a former residence of Lord Clancarty, a classic Anglo-Irish ‘Big House’, which was spared from burning in the Troubles on condition that it become available as an educational establishment. It was rather less than twenty miles from Athlone, and numbered among its 150 pupils boys of John Broderick’s own age from his home town. Although St Joseph’s was less austere than Summerhill, John again attracted some bullying from classmates, in part for his refusal or inability to conform. His mother was in the habit of despatching lavish hampers to him at school in the family car or in one of the bakery vans, which must also have set him apart from others less fortunate. But when necessary some of the Athlone boys would stand up for him, and his memories of Garbally were not unhappy. The great majority of the teaching staff at the time were priests and several were later mentioned by John Broderick with affection and respect. In particular, Father John Campbell, an English teacher, encouraged his interest in literature and writing, and introduced him to the work of Tolstoy.

Two volumes survive from this time among a collection of books left to the Athlone Public Library in Broderick’s will, a copy of Palgrave’sGolden Treasury, which he used in session 1939–40 and which is covered in the universal schoolboy scribblings of lists of poems to be learned, sonnet rhyme-schemes, an example of a Spenserian stanza and his own name signed several times over with varying flourishes; and a copy of Hilaire Belloc’sCharacters of the Reformation, awarded to John Broderick as first prize for Christian Doctrine.