Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Biteback Publishing

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

Brexit is unravelling. Amid the turmoil of plots, government defeats, resignations and riots, the United Kingdom's choice to leave the European Union and make its own way in the world has left the country more fractured than ever. At the heart of the chaos is Alan, a special adviser to a government minister; Mitra, a Labour MP; Jenny, a TV news producer; and Davey, a UKIP activist. Each will struggle to keep control of their own lives as they navigate a political environment that becomes more aggressive and unpredictable by the day. This sweeping novel takes its characters from the streets of Westminster to decaying towns, from the dingiest of pool halls to the heart of No. 10, and finally brings them all together for a debate in front of a live audience during the 2019 election. That night, there is more at stake than just politics; at least one of them is in real danger. Will they all survive – and if they do, will they be able to start draining some of the poison from the political world they now inhabit?

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 554

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

i

ii

For Angela

iii

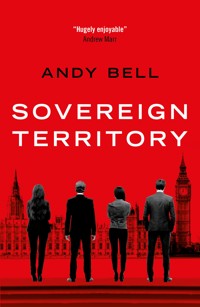

“The history of Brexit is being written and will continue to be written for decades. But what did it feel like being there, actually living through it, in the queasy, dangerous intensity of Westminster? Andy Bell had a ringside seat, and he tells the story in novel form with subtlety, sensitivity and a wonderful eye for the detail of Westminster Village life. Hugely enjoyable.”

Andrew Marr

“I always knew that Andy Bell was a top political operator and a master of TV news… I had no idea he had a brilliant novel in him too. He has taken the political drama he reported on and turned it into a gripping read.”

Dan Walker, presenter, 5 News

“Andy Bell has wrangled all the twists and turns of the Brexit referendum into a brilliantly observed thriller – as befits a political journalist who has been on the inside track for all the crucial political drama of this generation.”

Kirsty Wark, presenter, Newsnightiv

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE

NOVEMBER 2019

They had been live for nineteen minutes. In the old gym, now grandly rebranded as a sports hall, the broadcast was underway. On the temporary stage, raised just a foot or so off the polished floor, three men and two women stood behind lecterns. They gazed out at the noisy, restless room and tried to appear confident. Some succeeded better than others.

They were faced by an audience of about 150, who were banked up in a dozen rows of temporary seating. The overall impression was of bodies jammed in too closely. Many were agitated, others sat still but tense. None were calm.

Afterwards, veterans of live-debate programmes working that evening would say that from the start they had sensed something different. There had seemed to be too many people contemptuous of the hapless producers trying to impose some control. Too many of the audience had appeared ready to insult and mock those around them. An intangible sense of threat had hung in the room. Perhaps the atmosphere inside had been stoked up by the presence of the demonstration outside. That uninvited crowd, or mob, had set the tone for all those coming into the building.

The young producer of the programme had felt it but had pushed viiithe worry down. The ministerial special adviser watching from the side of the room had felt it but had trusted that the necessary security had been put in place. A young man in the audience had felt it too, but he had grown so used to a heightened level of aggression that he hardly felt it strange. The candidate behind her lectern had been aware of it too but had had no choice but to remain on the stage.

Later, no one would be able to tell the investigation that they had spotted the precise nature of the danger. A general sense of foreboding had not been enough to prompt anyone to intervene. Everyone knew that emotions had become more intense, but that was politics now, wasn’t it? You just had to accept that people argued in that way and that meant danger always crackled in the air of any debate. So the programme had begun as planned, nineteen minutes ago, broadcast live to a country enduring this winter election. It was as if everyone there had decided this process, set in motion so long before, simply had to play to a conclusion. So they had all watched and waited, sensing the approach of some undefined threat, but unwilling to stop it. The spell had only been broken when the police had erupted into the room.

JUNE 2016

The man on the screen summoned the attention of his unseen audience. ‘The people of Britain have voted and…’ he allowed himself the hint of a dramatic pause. ‘We’re out!’

The words fell into the room where Alan Jarvis sat. He imagined the announcement proclaimed across the country from millions of televisions and radios, springing up on phones and computers; history delivered in a sound bite. ix

‘Oh, bollocks.’ It was Alan’s boss who spoke. For the last two hours the apprehension in the room had been building, like a slowly rising tide. Now they knew. Britain was leaving the EU.

‘What an absolute fucking disaster. What happens now?’ Alan’s boss had just made it into the Cabinet. A Cameron loyalist and supporter of EU membership, he had campaigned hard for Remain, not just because he believed in the cause but because he thought he could expect promotion in a post-referendum reshuffle. His beliefs and his self-interest had coincided happily. Now he was staring at double disappointment.

They sat in the sitting room of his small Bayswater flat. There was the minister and his two aides, Alan and Kieron Gould. The minister’s wife had gone to bed not long after midnight, reassured by early results. Soon enough, she would hear the truth.

‘Cameron will quit, I suppose?’ Alan didn’t hesitate.

‘He’ll be gone by breakfast. Statement in front of No. 10.’

The minister groaned. In a couple of articles he had been singled out as a rising star. In the new universe, would he even have a place?

‘So who will it be? Boris? May? Not Gove?’

‘I guess Boris has to be the favourite…’ Alan watched the faces coming and going on the screen. A few looked delighted. Most looked stunned.

‘God help us. What do you think, Kieron?’

‘It’s amazing to think the same man announced the result on TV when we joined, isn’t it?’ Kieron was looking at the presenter on the screen. Alan heard the light Welsh accent and thought, not for the first time, how his colleague so often seemed to have no sensitivity. ‘Almost like history unravelling?’

‘Kieron…’ The minister was plainly irritated too. x

‘My money’s on Theresa. Everyone’s had a shock. Time for a steady hand. Boris is too risky.’

‘He’s just won them the referendum.’ Alan could sense the exasperation in his own voice. Even at this moment, he couldn’t stop himself trying to get the better of his colleague and rival. ‘He’s a hero to half the parliamentary party. If Boris makes it to the last two, he’ll walk it with the membership. They’re all over sixty and all Leavers.’

‘Well, I’m going to have to work out who to back. I suppose there’s no chance George will have a go?’ The minister was watching the screen. A prominent Leave-supporting MP had appeared. He was being careful not to look triumphant, but Alan knew the man. He knew that underneath that studied, statesman-like decorum, the MP would be relishing not just the result but the chaos that might flow from it; the chaos that might present a man like him with opportunities.

This time Alan and Kieron were in agreement. Both shook their heads.

‘I know,’ said the minister. ‘This is as much Osborne’s defeat as Cameron’s.’ He put his head in his hands. ‘Do you know what that idiot pollster of his said to me when I asked him if we should be worried? “The thing about David”, he said to me, “is he’s a lucky general.” A lucky general. Well, his luck just ran out spectacularly, and mine with it.’

Alan sat silent. There was a muffled shout from the television. On the screen a small crowd was cheering and waving in some half-empty town hall. Another small crowd watched them, sullen. Another result for Leave.

‘Come on,’ the minister said. ‘Help me draft a statement. A xiholding statement. Something to get us through the next few bloody awful hours.’

Davey couldn’t remember being so happy. He was still reeling from seeing Nigel, his face unhealthily shiny in the artificial light but his smile a mile wide, announcing that this would forever be known as our Independence Day!

They were all jammed in this strange cafe or club or whatever it was at the bottom of Millbank Tower. Yes, the same Millbank Tower where Tony Blair and his army of traitors had first set up ‘New’ Labour to throw the country open to as many immigrants as possible from the bloated EU. The irony had been remarked on several times, so many times that it was no longer interesting. But no one cared about that now, with the result confirmed and Britain – his beautiful Britain – escaping the European chains.

‘Davey boy! You little beauty, come here!’ Max grabbed him in a full-body, beery hug. ‘I knew we’d do it; I just knew it!’ Max’s sweaty face topped a white shirt and what looked like a regimental tie under a dark blazer, although it wasn’t. Overall, most of the other twenty- or thirty-something males in the room were wearing something similar. It wasn’t exactly a uniform, but it came pretty close.

‘I know, I know, it’s brilliant.’ In fact, Davey had never really expected them to win. Of course, he had had his hopes, but most nights – or early mornings – he had fallen into bed believing that the forces ranged against them were simply too strong: the big-party machines, the BBC, the beautiful people, business. The history was all against them. In every British referendum, the people had voted to stick with the status quo. Would they really take such a brave leap this time? He had kept quiet about his fears. It wasn’t good to sound xiidefeatist, even if he suspected a number of his fellow UKIP activists had felt the same. Despite that though, they had carried on, done their duty and in the end the people had astonished them.

Max had been one of those campaigning with him over the past few weeks. He suspected Max had never had any hidden doubts. In fact, it seemed that the more the facts stacked up against the cause, the more tightly Max was ready to hold to it.

‘A bunch of us are going with Nigel to the green opposite Parliament after this. We’ll make sure the best pictures for the morning bulletins are us celebrating – not any Tories.’ Max was shouting above the din of cheering, singing, laughing. A Conservative MP wormed his way through the tight-pressed crowd. He was a backbencher and a well-known Leaver, but Davey still found it odd to see him here.

‘Tosser,’ shouted Max in Davey’s ear. ‘He may have been on the right side in the end, but he’s still one of those bastards who wanted us to do all the dirty work. Still, if it’s a sign that’s the way the wind’s blowing…’

‘Boys, boys, boys!’ It was Kwam with a bottle of champagne but no glasses.

‘Drink up, we deserve it.’ Davey hugged his friend, a full-bodied embrace in the elation of the moment. They had found their way to UKIP around the same time, one from Slough, the other from the West Midlands. With a Ghanaian father and English mother, Kwam had grown up an outsider. ‘You think you’re an outsider?’ Davey had told him when they had first met. ‘That makes you a natural for UKIP, mate.’

‘Now we get our country back,’ said Kwam. ‘We can make our own laws, run our own borders, govern ourselves again.’ xiii

Max took a swig. ‘And get to make Britain the kind of country we want it to be.’ He handed Kwam the bottle, his eyes fixed on him. ‘The kind of Britain we used to have.’

There was a roar from the sweaty crowd. Another result had appeared on the screens suspended above them. ‘Birmingham!’ shouted Davey. It came out as more of a teenage squeal than he would have liked, but he didn’t care. ‘This is so sweet.’ Around him, the din was almost unbearable.

A few balloons appeared to hang from the ceiling, trailing their brightly coloured strings. In fact, they were locked there by their helium, as if they too were trying to escape this room where everyone no longer wanted to be. Around the gallery space that had been hired for what was supposed to have been a victory party, a few people stood listlessly. Some were crying. The TV monitors were relentlessly pumping out the results.

In one corner of the room on a slightly raised dais was the paraphernalia of a TV live position: two cameras, a table, some barstools, a lighting rig. A young woman sat on one of the stools, notebook in hand and headset on. Two cameramen stood in position with the air of men who had not had much to do for a while.

A young man crossed the emptying room. ‘He’s not coming, Jenny,’ he said. ‘His SpAd just texted me.’

‘Any reason?’

The young man shrugged. ‘The guy was apologetic. But I guess he just didn’t want to come on here. Not now.’

Jenny sighed. This was supposed to have been one of the focal points of the special broadcast: interviews with the leading lights of the victorious Remain team, discussions with the other side, live xivanalysis. For an hour now, the studio back at base hadn’t even bothered to cross to them. Now one of her last hopes, a guest booked days ago, had pulled out.

A middle-aged man made his way towards the makeshift studio. Grey at the temples, good looks, the wrong side of forty, he was the classic embodiment of the middle-ranking TV presenter, with the temperament to match.

‘So, what’s happening?’ He was barely civil.

Jenny took a deep breath. ‘He’s not coming, Malcolm. He’s pulled out.’

Malcolm swore savagely. ‘Well, tell him he can’t. Tell him he made a commitment. Just get him over here.’

‘I don’t think that’s going to work. Nobody wants to be at a victory party where there’s no victory. We’re just in the wrong place.’

‘You’re telling me we’re in the wrong place. I knew we should have been with the other lot. With Farage. Or Boris. Where’s Boris right now?’

‘He’s just in his house,’ said Jenny patiently. ‘And you didn’t want to go there and stand in the street, remember?’ Jenny certainly remembered. She remembered the meetings where the ‘talent’ had fought and wrestled – almost literally – to be deployed where they wanted to go. Malcolm had fought harder than anyone else to be here.

‘So what are we going to do now?’

Jenny knew she would have to manage the situation. At the very least, she didn’t want Malcolm slagging her off after this was over. ‘I’ve talked to the studio back at base, and they’re trying to divert one of the Leave side here. You can interview them here, in the very heart of the doom-stricken Remain campaign.’ xv

Malcolm grunted. ‘Will they let them in here?’

‘I don’t think they’ve got the heart to resist.’

Malcolm nodded. ‘OK. OK. But let’s make it happen, Jenny. Let’s rescue something from this disaster.’ He stalked off to an empty sofa and flipped open his laptop.

The young man was looking at Jenny. ‘Have you suggested they divert someone here?’

‘I did. But they’ve made it pretty clear they’re not interested in doing that. I just needed something to calm Malcolm down a bit.’

The young man nodded. ‘Still, it’s quite a story isn’t it?’

Jenny looked at him. With all the cancellations and the changing programme demands, she had barely thought about the actual result.

‘Quite a story?’ she said. ‘It’s the biggest story that’s happened to this country since… I don’t know. Since the war.’

‘The Iraq War?’

‘No,’ she said, exasperated, ‘THE war. World War Two. This is going to throw everything up in the air. I suppose Cameron will resign. And that will just be the start of it.’

The young man nodded and smiled. ‘Cool. It’s so much more interesting than if it had gone the other way.’

‘Yes, that’s one way of looking at it.’ Jenny had thought it would be close. She had been round the country enough with the news team to know there were large pockets of voters who were eager to seize what they saw as the first meaningful vote in their lives. ‘I haven’t voted in an election for twenty years, but I’m voting this time for sure.’ She’d lost count of the number of times she had heard that, and it had been obvious which way those saying it were going to xvivote. Well, they’d done it now. Interesting? It was certainly going to be that.

Mitra Vakil was on the phone to her election agent, but her eyes were fixed on the TV screen. She was in the sitting room of the two-up, two-down terraced house she had bought in this part of Coventry when she first fought the seat for Labour six years ago. It was just a couple of miles from the house where she had grown up, but despite that, or maybe because of it, the place had never really felt like home. Still, it was somewhere she could feel secure when the outside world felt too much like a bad joke at her expense. Like tonight.

‘Do you think there’ll be an election? I mean, Cameron will quit, won’t he? What happens now, Barry?’

In her ear she heard Barry’s reassuring West Midlands voice. He spoke slowly, and some people assumed that meant he wasn’t too sharp. That was their mistake.

‘In the order of your questions, Mitra: no, yes and I haven’t got a bloody clue. Most importantly, we don’t have to start gearing up for an election quite yet. The Tories will have to find someone to replace Cameron. Boris, I imagine.’

‘Well, that’s a relief. Not the Boris bit, but the election.’ Mitra saw the face of a Labour MP who had taken a frontline role in the Leave Campaign. ‘Oh, yes, well done. You feeling pleased with yourself now, you silly cow?’

‘I assume that’s not aimed at me.’

‘No, Miss Self-Righteous on Sky right now. But where’s Corbyn? He hasn’t shown his face yet. He’s got a lot to answer for.’ The Labour leader had come to Mitra’s constituency during the campaign. xviiHe had supposedly come to rally the Labour troops to push for a Remain vote. He had spoken in a hall that stood on the site of some courthouse that had been demolished many years before. Corbyn had started his speech enthusiastically because some workers had been jailed in the old courts in the nineteenth century for trying to organise a union. Without notes, he had exhibited passion and charisma and he had warmed them all up nicely. Mitra had sat back waiting for him to move into the part about Europe and the impassioned call to get the Labour vote out for Remain.

It never came. Instead, he had unfolded a sheet of A4 that he didn’t seem to have seen before and begun a painful rehearsal of words clearly written for him by someone else. The excitement had gone out of the room. Afterwards, she had found about half of those who had promised to knock on doors had drifted away.

‘I’ve already had a text from Jim,’ said Mitra. ‘There’s going to be a vote of no confidence in him. Everyone’s disgusted with him.’

‘Are you going to join it?’

‘Yes. He’s just flunked the biggest test of his leadership. Leaving the EU will be disastrous for our people, but he doesn’t seem bothered. We all know that he basically thinks it’s a capitalist construct, but we hoped someone might have convinced him there were real jobs at stake.’

‘Well, you have to decide if it’s right to go for no confidence. He’s still got a lot of support in the party. Outside Westminster, I mean.’

Mitra looked at a framed photograph on her bookshelf. It was of a smiling teenager holding a leaflet saying, ‘Vote Labour.’

‘Yes, my son among them. But the young ones are all against Brexit. Surely this will dent their faith in him?’

‘You have to do what you think best, Mitra. I am just here to give xviiiyou a little guidance about the constituency. And by the way on that, we haven’t got the numbers yet, but I think Coventry Moorside voted out.’

‘That wouldn’t surprise me.’ Mitra had toured her constituency in the campaign and had been shocked at what she found. It wasn’t just Labour voters happy to give Cameron a bloody nose. It was Labour voters who wanted their country back, who were convinced their wages were being held down by immigrants, that their children were being kept out of council flats by immigrants, that they couldn’t see a doctor because there were too many immigrants. There was a lot of what she could only describe as old-fashioned racism, and it wasn’t just about the Poles and the Romanians. For the first time in a long time, she had felt uncomfortable on the streets of her own constituency.

‘OK. I’m going to get some sleep now and head to Westminster first thing. I think this thing is going to get rolling with Corbyn and I need to be there.’

‘All right,’ said Barry. ‘You do that. I would like to give you some wise advice, but with the way things are right now, anything I say will probably be proved wrong by lunchtime.’

APRIL 2018

I

Alan Jarvis made his way down Whitehall. He threaded through the knots of tourists, who moved slowly down the pavement, looking this way and that, taking in the sights of this most historic part of London. The grandeur of the Treasury and the Foreign Office; the almost-deranged, gothic extravagance of Parliament; the statues of the great and the good, starting – of course – with Churchill in the square.

Across the road he could also see them clustered around the gates of Downing Street, some listening to a guide speaking Mandarin and holding up a multicoloured parasol. In among them were a couple of TV crews. It was Cabinet day, and they would have been sent down to doorstep any ministers who hadn’t been ferried up to No. 10 by official car. Unwary ministers might make the mistake of engaging with them in the fifty or so yards they had to walk before they could duck into their ministries or the parliamentary estate. Even then, they tended to say virtually nothing, but Alan always marvelled at how much the journalists could milk from a short and arid exchange for that night’s bulletin. He always made a point on Cabinet days of going down the other side of the street and avoiding the gaggle at the gates. There were times when he needed to 3engage with journalists, but outside Downing Street with cameras present was not one of them.

He crossed the road up by the Women’s War Memorial and went through the blue door of the Whitehall entrance of the Cabinet Office. Once in there, he enjoyed the feeling of being inside the estate, connected to No. 10, the old Admiralty building and the various locations that made up the Prime Minister’s domain.

The Cabinet Office had always been a bit of an anomaly. The Department of Health and the Ministry of Defence across the road housed ministers and civil servants with specific responsibilities everyone could grasp. To Alan, even with his experience, the Cabinet Office had always seemed to be detached from the conventional government machine, sometimes playing a decisive role, sometimes falling through the cracks. Now, though, the building at least had another purpose. In the summer of 2016, Theresa May had chosen it to house her new ministry, the Department for Exiting the European Union. And it was his new home.

Much had changed but much remained the same in the two years since the vote, for Alan Jarvis as with the country as a whole. Alan was still a SpAd to a minister but a new one. Britain was still in the EU but poised to dive into a future that was, depending on your point of view, terrifying, uncertain or inspiring.

He made his way up the stairs past the whitewashed walls with the black-and-white prints of London. The external appearance at least conveyed the impression this was a working part of the government machinery. In the first months after the announcement of the special new department, it had been horrendous. New offices being created with cheap partitions, wiring running down corridors 4as computers and routers and phonelines were put in. Stunned civil servants, many of them drafted against their will, tried to establish just what they were supposed to be doing. The growing realisation of the scale of the challenge had been matched by the inadequate resources being installed. At least the offices now worked – even if the staff hardly stayed long enough to make use of them.

Alan pushed through a slightly open door. Inside were three desks, one of which, his in fact, partly obscured what should have been a charming Georgian-style window looking onto a small garden between the back of the Cabinet Office and the side of No. 10. To the left of his desk was the one belonging to Jo Marks, the minister’s private secretary, and directly opposite him was that of Steve Cole, the minister’s other special adviser, who was responsible for the more technical side of the brief. Every day, Alan thanked God for Steve. Brexit had turned out to be a festering, toxic onion. You peeled off one layer of problems you thought you’d fixed, only to find another set below that, and another below that, and another. These were the accumulated complexities of rules and regulations no one had even thought of until they had to be unravelled. Mercifully, if the minister needed an answer to this kind of problem, it was Steve’s job, not his, to come up with it. Yes, thank God for Steve.

‘Morning, Jo.’

‘Morning.’ Jo Marks didn’t do a lot of small talk. She had worked with the minister before his transfer to DEXEU and they were clearly close. The minister had asked for her to be transferred in as the new department was created. At least once a day, she would disappear into his adjoining office and the door would be closed, and she was nearly always there at the end of the day when Alan and Steve went home. Alan wasn’t sure if there was anything going on, 5but he wouldn’t have been surprised to find out there was. He had hardly ever seen the minister’s wife, who buried herself in Dorset and seldom came to town. As long as it didn’t become a problem for him, Alan was happy not to think about it.

‘Is he in?’ Alan pointed to the closed door of the minister’s office.

Jo didn’t look up. ‘Yes, he’s just on a call.’

‘Oh, who with?’

‘Just a private thing.’ Jo still didn’t look up. The clear message was that Alan didn’t need to know. ‘He’ll be done in a minute.’

Alan settled obediently at his desk and opened up his computer. The minister with whom Alan had watched the referendum result two long years ago had been swept away. He had first been shuffled sideways by the triumphant Theresa May and then lost his seat in the 2017 election. His Remain credentials had not been enough to save him from the vengeful backlash in his part of the London suburbs. He was doing something with a transport lobby group now. Alan hadn’t spoken to him for a long time.

The new minister was a long-standing Leave supporter of solid credentials. He had been on the campaign trail but in a modest way. He had not courted the wilder fringes of the Leave landscape. He had not been on a platform with Nigel Farage or George Galloway. In short, he had stuck to the correct lines to ensure that, however the vote turned out, he would not have burnt any bridges. He had to bide his time a little when May took over, but in the bloodbath after the failed snap election, his moment had come. When the PM needed ministers who wouldn’t spook the markets but who had convincing Brexit backgrounds, he got the call.

Alan had been grateful to get the call too. After his first minister had disappeared, he had wondered whether that would also be 6the end of his career. Special advisers have even less job security than their bosses. Alan had spent several days hanging around Westminster, fearing that his parliamentary pass was about to be withdrawn and his access to that absurd but marvellous labyrinth would disappear. He had brushed up contacts and sent congratulatory messages to those getting new jobs or hanging on to old ones, all the time trying to strike the right note between polite enquiry and desperation.

Then, when he had almost given up hope – that is, after about three days – he had received a call from someone in the new team in No. 10. They had worked together long ago on the electoral reform referendum. There was a bit of history there and each knew that in different circumstances their present situations could have been reversed. Things were going to get even more difficult in DEXEU and the minister there would need some extra firepower. Could Alan help out? Alan had stayed professional on the phone and had solemnly said what a privilege and a responsibility it was to be at the centre of unfolding events. Of course, he would be very happy to accept the role. Passers-by in St James’s Park that afternoon would have seen an intense young man holding a mobile and punching the air.

The door to the minister’s office swung open. Alan looked up. His minister was there in shirt sleeves, looking like a man ready to get down to some hard work in the nation’s interest.

‘Hi, Alan. Can we talk? The select committee in two days. Need to be on top of that.’

‘Of course.’ Alan started to get up.

The minister held up a hand. ‘Just give me a minute with Jo. Some diary stuff to sort out.’ 7

Alan sat back down the half a foot or so he had risen from his chair. Without a word Jo pushed back her chair and strode past the minister into his office. The door shut behind them.

Alan swivelled round so that he could look onto the little garden. His view also took in some bins at the side of No. 10. When journalists were brought in for a big event like a press conference inside, they had to enter through the side door, like tradesmen or embarrassing visitors to be hidden away. Even the grandest of them had to go by those bins.

His phone buzzed. It was a text from Ashish. ‘Looking forward to seeing you later. X’. Alan allowed himself the slightest smile. He was looking forward to seeing Ashish too. He must remind him to stop texting the work phone though.

Davey sat in his car and tried to keep his anger down. These days, this often seemed to be an almost physical sensation, as if he could feel something rising from the pit of his stomach that he could not control. It hadn’t always been like this. He had lost his temper in the past, sure, but that had been instant. Now, he was much better at controlling himself, and of course that was an improvement. All the same, he could now spend minutes, maybe longer, where his anger almost felt like a tumour inside him. Even if he now had more control, it didn’t make him feel any better.

Right now, he was angry with Kim and Angus. They had been supposed to meet him here in Ealing to view a flat at 2 o’clock. At 1:43, Kim had phoned the office to apologise, but they would not be able to make the appointment. No, they didn’t want to reschedule. Thank you. Goodbye.

Davey had been hoping they were closing in on a sale. The 8two-bedroom flat with kitchen, sitting room, bathroom, ten minutes’ walk from not one but two Tube stops was going begging for 455. Kim and Angus seemed to have the money. They drove a nice enough car, an Audi, and their clothes looked decent quality. Kim especially had a nice voice that whispered family money. This would have been the second time they had come to see the place. He had heard Kim tell Angus after the first visit that it was the best they’d seen. And now that was it; just a cancellation. And they hadn’t even called him directly. Instead they had phoned the office, no doubt not brave enough to confront his disappointment. Typical; posh, privileged cowards.

Davey sat in his Mini, a car badged and striped with the livery of his employers. He had been excited when he realised he would get a car with the job. Now he hated the garish mobile advert in which he had to drive around. He saw people watching as he drove by, their faces closed but no doubt thinking, ‘There goes another fucking estate agent.’ Sometimes, he didn’t have to imagine. Sometimes, people just gave him the finger as he drove past.

He should go back to the office. They would know that his appointment had been cancelled, and there were strict rules on how he should use such unexpected free time. He should be back at his desk as soon as possible, following up leads and calls, not resting until he had initiated more chains of interest that just might culminate in a sale. It was how he was supposed to spend his ‘lunch break’ too.

Davey knew that was what he was supposed to do, but he just couldn’t. It wasn’t just the frustration of the work; it was the other people in the office. Most of them were all right most of the time, but he never felt he could completely relax. This stemmed from 9his first week, when he had mentioned that he had voted Leave. It had been soon after the referendum, and he thought that everyone would at least recognise that the country had chosen. Surely, he didn’t have to feel like the odd one out any more? There had been a majority for Leave for God’s sake.

There had been about half a dozen of them there at the end of the day, and he had felt the temperature drop. After a moment, Hannah, an attractive blonde whose strong personality set the tone for a lot of what happened in the office, said, ‘Well, thanks, mate. I had a plan to move to Spain next year. Not going to happen now, is it?’

Davey had tried to put over all the arguments in which he was so experienced, that of course she would still be able to move to Spain, it was in everyone’s interest to come up with sensible arrangements, but he had felt his words dry up. As he was speaking, people started picking up their bags and moving towards the door. It just wasn’t an argument anyone wanted to have any more. Even Hannah had just looked through him and said goodnight. It wasn’t exactly hostility he had felt from them all; it was more a wariness. He had not conformed, and they had not known how to handle him. Afterwards, he had gone for a drink with Will, who had started around the same time as him. ‘I wouldn’t worry about it,’ Will had said after their second pint. ‘It’s just not what they’re used to around here. At least you didn’t say something really weird, like you were a member of UKIP or something.’

So, Davey kept his guard up. He could rub along well enough, but he never felt he could truly engage with the others in the office, and they sensed he was holding something back. As a result, he found himself excluded in small ways. He would see the knot of 10people he felt sure were heading to the pub when he wasn’t invited. There would be someone’s jolly reference to what had happened at the weekend, silenced by a meaningful exchange of looks. It all still rankled, but he was getting used to it. He didn’t need them anyway.

He’d be seeing Max tonight, which normally cheered him up. Although these days it wasn’t quite the same. It seemed that ever since the referendum, everything had been a disappointment. Obviously, it was always going to be difficult to match that moment, but even so, there hadn’t been much to cheer since Nigel had gone. The election had been a disaster, and worst of all, Brexit looked like it was going to end up as a complete sell-out. Well, what did you expect if the people running it were all Remainers? They had never wanted it to happen and they still didn’t. To them, leaving the EU was a damage-limitation exercise, not the glorious liberation it should be. Betrayal. It was the only word. And traitors. That’s what they were. Davey sat in his car and breathed deeply.

In the studio, the lights dimmed around the five seated figures. The signature music drummed to its end. In the gallery, the red ‘On Air’ light went out. The director leaned in to a microphone that arched towards him like a giant metal insect’s antenna. ‘We’re out,’ he said and sat back.

Jenny stood up from her seat next to him. ‘Thanks, Jim,’ she said. ‘Immaculate, as always.’

‘Flattery. It doesn’t work you know,’ the director said without looking at her. ‘But please carry on.’

Jenny touched him lightly on the shoulder and gave him her brightest smile in the glass that separated them from the studio. He 11smiled back at her reflection. She liked Jim well enough and it was always good to keep on the right side of people like him; directors could get producers like her out of a whole lot of trouble, but only if they wanted to.

She walked round to the green room, where the guests were already getting ready to leave. She barely had time to thank two of them: a Liberal Democrat MP and the boss of a small engineering firm who doubled as a spokesman for an employers’ organisation.

‘I tried to stop him,’ Mel the make-up lady said, ‘but he was gone before I could. Without me taking it off he’ll look a bit suntanned out there.’ She made a face.

‘Maybe he likes it,’ said Jenny. ‘He’ll probably start popping in even if he’s not on the show.’ Never underestimate the power of make-up in TV, thought Jenny. There had been a female boss of a charity who had developed a habit of turning up at the Westminster studio, claiming she had been booked to appear. While they tried to get to the bottom of the mystery booking she would say, as if it were the most natural thing in the world, ‘I might as well get a little make-up while you’re working it out.’ By the time it was established that no one had booked her, she would rise radiant from the makeup chair and sweep out, even complaining about the mix-up. She was now banned.

The show’s presenter, Gary Bond, was talking to the two remaining guests. Geoff Miller was a rising Labour star; in Corbyn’s shadow Cabinet but skilfully cultivating an independent side. The other was Maggie Richards, Conservative.

‘I don’t really know what Theresa is playing at, if I’m honest,’ she was saying, her words forcefully filling the room in a Yorkshire 12accent. ‘I voted for her and I’ve stuck by her through all this, but I don’t see how she gets this through Parliament.’ She swung round as Jenny approached. ‘This is off the record, right?’

Gary nodded. ‘Of course.’ Jenny nodded too and sent a pointed look at Mel who obediently left the room.

‘I mean, how does she win a vote in the Commons? Only with help from your lot,’ she pointed at Miller, ‘and I just don’t think there will be enough.’

‘When it really comes to it, how many Tory MPs will vote against her plan?’ Gary had asked this question during the live broadcast that had just finished. Richards had essentially dodged it. As so often, the answer given once the camera was turned off was much more interesting.

‘Twenty-five,’ Richards shot back without hesitation. ‘It might even be more. Are there really going to be that many Labour MPs who will vote with the government?’

‘We will all stay true to the leader,’ said Miller. How like him, thought Jenny; explicitly loyal, while implicitly you could read almost anything into his answer.

‘Oh, piss off,’ said Richards. ‘I should have known better than to expect a straight answer from you.’ She was smiling as she spoke. These days, the real bitterness was reserved for people in your own party.

‘She has managed to steer things this far,’ said Gary. ‘You have to admit, she has a knack for somehow keeping the show on the road.’

‘Well, she’s going to need more than a knack to get through the next bit.’ She sighed in a way that for a moment appeared to deflate her. Then she straightened up. ‘Right. I’m off. Thank you for the show; time for lunch now. You coming, Geoff?’ 13

‘What, to lunch with you?’ Geoff Miller smiled teasingly.

‘No, just back to the House, you wazzock. Why would I want to have lunch with you? Toodle-oo, everyone.’

Jenny and Gary listened as the two MPs disappeared. ‘I don’t know if I should be seen with you,’ they heard Miller saying. ‘It’ll do your reputation a lot of good, sweetie,’ came the reply, and then they heard no more.

Jenny turned to Gary. ‘Good programme,’ she said. ‘I think there’s a line in there from Richards. About the need for the EU to move on the backstop.’

‘Playing Russian roulette with the peace process – yes, definitely need to push that to the desk.’ He moved towards her. They were alone in the green room. The door was slightly open. ‘I’m glad you’re happy.’ He was close to her now. In a jammed Tube train, the distance between them might have been acceptable. Here, in this place, it was evident what was happening. Jenny looked at the door. She could hear no one. No one who might help her. Or disturb them. She grasped Gary’s hand.

‘Not now,’ she said. ‘Later.’

The sound of dozens of conversations floated in the space below the glass ceiling, the voices heard as if underwater. The liquid quality of the gentle, murmuring sound put Mitra in mind of a Victorian train station or even a cathedral – not that she had spent much time in cathedrals. Instead, this was the great meeting place of Parliament known as Portcullis House, where MPs, their staff, journalists and even the occasional Cabinet minister might search out coffee, gossip and intrigue. It was not a place for conspiracy; it was too open for that. But it was certainly somewhere you might pick up the 14quiet undercurrents of Westminster and then be able to share them over an agreeable flat white.

That was what Mitra Vakil was doing with another Labour MP from the West Midlands. Linda Baramian and Mitra had both been elected for the first time in 2010. Their personal triumphs that night had been blunted by Labour’s loss of power after thirteen years, but they had all been braced for it. In fact, the result had been less bad than most had feared, and there had been that strange weekend when it seemed Gordon Brown might even remain Prime Minister in some kind of coalition. Instead, another coalition had taken shape and Mitra and Linda knuckled down to opposition and promoting themselves in that strange talent pool unique to Parliament.

They had both been loyal followers of Ed Miliband and had keenly felt his defeat; there had been a tearful embrace in Mitra’s office when they watched him resign the morning after the 2015 election. Neither of them had expected what followed. The candidates each of them had backed for the leadership were swept away by the Corbyn tidal wave. It would not be the last time they would see conventional political wisdom turned on its head. Now, they sat and rehearsed an argument that had become familiar to them both over the past few weeks.

‘I just don’t see it, Linda.’ Mitra stirred her coffee and fixed her friend with a direct, open look. ‘At my surgery on Friday, this guy came along. He was complaining about some planning permission, or something like that. Not sure what I was supposed to do about it anyway. And when he gets frustrated that I can’t fix it there and then, he just starts up with, “I should have known better. You lot 15won’t even make Brexit happen. We gave you an instruction and you won’t do it.”’

‘I know plenty who say the opposite. They think now they were lied to.’

Mitra shook her head. ‘For every one of those there are two of my guy. Certainly in my constituency.’

‘Come on, Mitra, you know the damage leaving is going to do. Especially in constituencies like ours. I think there’s a real path opening up to a second referendum.’

‘A people’s vote,’ said Mitra, with maybe just a shade more sarcasm than she intended.

‘Yes, a people’s vote,’ said Linda, ‘because the people certainly didn’t know what they were voting for last time.’

There was a slight disturbance in the atmosphere of Portcullis House. A group was moving across the room. There were only five of them, three men and two women, but they moved with purpose in a way that sent out the message that they should not be intercepted, that they had somewhere to be and business to transact that was more important than anything anyone watching could imagine. In the middle of the group, the centre of an informal but protective ring, was Jeremy Corbyn.

Mitra and Linda watched the bearded figure crossing the room, a slight smile on his lips. ‘Well, he’s not going to budge,’ said Linda. ‘Not unless he has to.’

‘But maybe he’s right,’ said Mitra. ‘I’ve got a 58 per cent Leave vote in my constituency. They’re not going to thank their Labour MP for ignoring their voice first time round. At least while we hold fire, the Tories are tearing themselves to bits.’ 16

‘And the country? The future? What about that?’ Linda, for the first time, sounded genuinely exasperated. There was an awkward silence between the two friends. Then Mitra’s phone vibrated with a text.

‘Simran’s here. I have to go pick him up.’

‘Send him my love.’

‘You going to come and say hello?’

‘No. I need to get going. I’ve got committee prep I need to do before we sit.’ They stood and hugged. ‘The struggle continues,’ said Linda.

‘See you soon, comrade.’

Simran was waiting on the other side of the security check in the entrance to Portcullis House. The sight of her son sent a little thrill through Mitra, as it always did. She liked to think he embodied the best features of his parents: his father’s build and blue eyes, her strong features and thick black hair. She remained almost irrationally proud of him. These days, though, there was also that edge of tension. She caught his eye and waved. He raised his hand. Barely. Through the glass doors behind him, Mitra could see the Thames and the South Bank, hunched under a grey sky.

‘Hello, darling,’ she gushed as she hugged him.

‘Hello, Mum. Was that Jeremy I just saw going through?’

Mitra did her best to sound relaxed. ‘Yes, that was him.’

Simran nodded. ‘Cool. Eddie got to meet him last week. He was up in Hoxton; just a low-key thing. Eddie spoke to him about his thesis on Britain’s complicity in the slave trade.’

‘I thought Britain was the first to ban the slave trade?’ said Mitra. ‘And then we used to intercept slave ships?’ 17

Simran smiled the little grin that had started to annoy his mother so much. ‘So naïve, Mum,’ he said, drawing out the second word. ‘Of course the history books in your day said that. But there’s a lot of new research showing there was so much hypocrisy, and, and… collusion. Eddie’s got some really good stuff. Jeremy asked him to send him a copy when he’s finished. He sounded really interested, apparently.’

‘I’ll bet he did.’

‘Can you introduce me to Jeremy? I mean, I know you’re not a fan.’

Mitra sighed. ‘I am a loyal foot soldier—’

‘Since he won twice.’

‘—but I do have my differences. Come on. Quid pro quo, come and help me with some correspondence, and if you’re lucky, I will get you an audience with the dear leader.’

II

They had been in the minister’s office for an hour and Alan could feel his eyelids drooping. He kept trying various tricks to keep himself alert. He discreetly pinched the flesh behind his knee; he made himself sit up so that the muscles in the small of his back hurt. He even tried to concentrate very hard on what his colleague Steve was saying. That was the least effective trick of all.

‘So unless we can find something to replace EU law 51861, British firms will have to find another way to gain access to data from EU citizens. This is the kind of data that companies need all the time, and they have gotten completely used to having total legal access to it. Without that information about customers and potential customers, UK businesses will be at a real disadvantage.’ Steve paused for the first time in what Alan thought must have been a hundred years. It was probably about four minutes.

Behind his desk, the minister held a pen. At the start of the meeting, he had made notes. Alan was pretty sure, though, that for the past twenty minutes, the pen had not touched paper. Still, the whole pen-holding routine conveyed a good impression of someone absorbing and sifting complex information; certainly a better impression than Alan had been giving.

There was a pause that someone needed to fill. Alan did not want 19to do it, but he dreaded Steve ploughing on. Mercifully, just as Alan was opening his mouth, the minister spoke.

‘So why can’t we just do that, then? Just tell Brussels that we will honour all the commitments we currently do and then legislate, putting in whatever we have to in order to keep them happy?’

‘There have been some preliminary discussions along those lines—’

‘Preliminary discussions? It’s more than two years since that bloody vote.’

‘Yes, but there has been a lot for everyone to keep across. And the EU has very definite ways of doing things.’

The minister rolled his eyes. ‘So where have these discussions got us to?’

‘They are not as advanced as we would like. The view in the commission is fairly strict.’

‘This sounds bad. So what have they said?’

‘That we can’t have it.’

‘Can’t have what?’

Steve shrugged and grinned a sheepish apology. ‘Access. Or rather, the same access as now.’

‘Why not?’

Steve spread his hands. ‘The data-sharing rules are for member states. Britain cannot have the same access when it is no longer a member state.’ He shrugged. ‘It is pretty straightforward really, when you think about it.’

‘But don’t they want us to carry on doing business with them? All the services we provide? It’s so inflexible. And short-sighted.’ The minister swung his gaze round on to Alan. ‘You’re very quiet.’ Alan couldn’t tell whether his boss was exasperated with him or 20with the EU. Sometimes, he thought they were almost friends. Then there would be a look or a comment that would remind him this would never be that kind of relationship.

‘It’s like everything. Like… Galileo, that’s probably the best example,’ said Alan. ‘It’s clearly in our interest and the EU’s interest to keep us inside the Galileo satellite project. We have done a lot of the work, we have so much more to contribute, and they will benefit from all of that. But instead they just say, “Galileo is not open to non-EU members.” And that’s it. Their club rules trump any kind of pragmatic deal.’

‘So, back to the original question: how do we replicate the data-sharing rules we have now?’

‘That’s easy,’ said Alan. ‘Stay in the EU.’

‘Ha bloody ha. Is that what I’m supposed to tell the committee?’ Alan realised he had made a mistake. He tried to recover.

‘It’s not unreasonable to inject a little realism into this. The country has voted to leave, and that’s what we’re doing, fair enough. What people shouldn’t do is say that we will get to keep all the things that we like; people should be prepared to say that to get what we want – basically the end of free movement – we are going to have to lose some other things.’

The minister looked at Alan. ‘You voted Remain, I’m guessing?’

Alan shifted uncomfortably. ‘Yes.’

‘Well, don’t worry; I think just about everyone else who works in this building did the same. Except me. I still think leaving is going to be the right thing in the end. We just have to get through this bit, and I’ll confess, I didn’t expect it to be quite such a shitshow. I was never one of those starry-eyed zealots who said we’d get everything we wanted because the Germans would cut a deal to sell us loads 21of BMWs. But I do think in the end business, money, will make the difference. In the meantime, at the very least, we have to look like we know what we’re doing.’ He picked up a file. It was marked ‘international contract law’ and it looked about an inch thick. ‘OK, onto the next – take it away, Steve.’

Max was making his way back from the bar with the drinks. Davey waited at the corner table. The first pint had gone down fast, but it had not helped to take the edge off his mood. Something was still grinding away in his head, here in the noisy pub surrounded by the white noise of apparently carefree young people who had finished work for the day.

‘Get that down you,’ said Max, putting the lager in front of Davey.

‘Thanks.’ The two friends took long drinks. Davey felt the alcohol moving through him. He knew from experience it would either lift his mood or darken it. It was still too early to tell which it would be this evening.

‘Why don’t you chuck it in if you hate the job so much?’ Max had listened to Davey’s almost unbroken complaint from the moment they had first sat down.

‘I’d love to, but what would I do?’

‘Come on, London’s full of jobs. No one’s got an excuse to be on benefits here.’

‘What, with all those Poles and Latvians and all the other fuckers coming in?’

‘Is that the kind of job you want? Shovelling shit on a building site?’

‘Obviously not.’ Davey shrugged. ‘I don’t know what I want. And anyway, it might not be any better wherever I went. It’s the people that piss me off.’ 22

‘Yeah, well that might not be any different. Down here anyway. You could go back home?’

Davey took another drink. ‘To Coventry? No thanks. There’s no work there. Anyway, I want to be in London, where the action is.’

‘Well, what do you want me to say, Davey? You don’t like your job, but you don’t want to move and you don’t know what you want to do. And you don’t like the people you share a city with.’

‘It’s all right for you; you’ve got a nice little number.’ Max now worked for one of UKIP’s MEPs. As far as Davey could see, there wasn’t much work involved, but there was a fair amount of expenses-paid travel to Brussels and Strasbourg. Max’s effort mainly went into promoting his MEP and organising events in the UK.

‘You’ve got the money and you’re still doing something worthwhile. Keeping it going. While all these fuckers are trying to derail it.’

Max smiled. ‘Yep, can’t argue with that, Davey boy. Sorry. We almost got you in there.’ After the referendum, Davey had virtually been promised a job with another MEP, but at the last moment she had defected to sit as an independent, saying she could no longer work with the party. She had offered to still take him on, but Davey had said no. He had told her he was still UKIP even if she wasn’t, so his conscience wouldn’t allow him to work for her. She had politely accepted that and wished him luck. Davey had hoped word might have got round the party and his principled stand might have led to another offer. It hadn’t.

‘Anyway, you know it can’t last. Soon, we won’t even have any more MEPS, or their assistants.’ Max smirked. ‘I used to love it when Nigel said, “My dream is to make myself redundant.” Of course, I’m still happy it’s happening, but I guess I never thought it would have such a direct impact on me.’ 23

‘If it happens,’ Davey said angrily. ‘If it happens. The way things are going, they could delay the whole thing. We might be stuck in this for years yet. Your job could be safe for a while.’

They fell silent and looked around the pub. From their corner seat, they had a good view of the Thursday-night clientele. Mainly twenty- or thirty-somethings, well turned out, animated, enjoying life or at least determined to convince themselves that they were. In this pub between Whitehall and the Strand they had come from the offices of government departments, solicitors, the odd start-up. They worked as managers, accountants, lawyers, analysts of various stripes, media and PR execs. They were the workers who kept London turning like a turbine, the people who had jumped on a locomotive that had been running since before they were born, which appeared to offer wealth and possibilities that could not be found anywhere else in the country. They had imagined the turbine turning faster and faster, growing bigger, generating more and more with limitless potential. They had gazed on this wonder of the modern world and, with the hopefulness of youth, embraced it. They had all voted Remain.

Max surveyed them. In many ways, he was not very different. He had grown up in an outer-London suburb. All his life, he had been aware that his town was orbiting the great city just over the horizon. He too had found it exciting, initially, the trips up to clubs and gigs and the thrill of the illicit, which his hometown could not provide.