18,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: ibidem

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

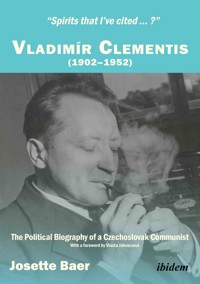

Baer’s biography of the former Czechoslovak Foreign Minister Vladimír Clementis (1902–1952) is the first historical study on the Communist politician who was executed with Rudolf Slánský and other top Communist Party members after the show trial of 1952. Born in Tisovec, Central Slovakia, Clementis studied law at Charles University in Prague in the 1920s and had his own law firm in Bratislava in the 1930s. After the Munich Agreement of 1938, he went into exile to France and Great Britain, where he worked at the Czechoslovak broadcast at the BBC for the exile government of Edvard Beneš. After the Second World War, Clementis’ political career at the Czechoslovak Foreign Ministry blossomed: In 1945, he became Assistant Secretary of State under Foreign Minister Jan Masaryk. After Masaryk’s mysterious death in 1948, Clementis was appointed Foreign Minister. This biography offers an unprecedented insight into the mind of a Slovak leftist intellectual of the interwar generation who died at the command of the comrade he had admired since his youth: Generalissimus Stalin.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 583

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Ähnliche

ibidem Press, Stuttgart

Table of Contents

Abbreviations

Acknowledgements

The Drama of Vladimír Clementis The Tragic Life of a Communist

X. Introduction

X. 1 Vladimír Clementis – victim of Stalinism or gravedigger of democracy?

X. 2 Analytical framework and conceptual matrix

Analytical framework

Conceptual matrix

X. 3 Method, key issues, research interest

X. 3. 1 Method: contextual biography

X. 3. 2 Key issues

X. 3. 2. 1 Czechoslovakism and the Czechoslovak Nation

X. 3. 2. 2 Antisemitism

X. 3. 3 Research questions

I. Childhood, Education and Pre-War Political Activities (1902–1939)

I. 1 Childhood in Tisovec

I. 2. DAV and the Davists

I. 2. 1 The Themes of DAV – Applying Marxism-Leninism to Slovakia

I. 2. 1. 1 The Question of the Czechoslovak Nation (1924)

I. 2. 1. 2 Agrarian Thought as New ‘Ideology’ (1924)

I. 2. 1. 3 The Electoral Defeat of the Communists (1929)

I. 2. 1. 4 The Trips to the Soviet Union (1929, 1930)

I. 2. 1. 5 The Anti-Soviet Press Campaign (1935)

I. 3 Black Whitsuntide in Košuty (1931)

I. 4 Member of Parliament (1935–1938)

I. 4. 1 On National Security (1936)

I. 4. 2 Lex Sidor – on Slovak Antisemitism (1937)

I. 4. 3 A Farewell to President Masaryk (1937)

I. 4. 4 On Slovak Autonomy (1938)

I. 4. 5 Munich 1938 – The End of the Republic

II. In Exile (1939–1945)

II. 1 From France to Great Britain (1939–1940)

II. 2 In Great Britain

II. 2. 1 Lída’s Living Conditions

II. 2. 2 A Political Decision

II. 3 The BBC Broadcasts (1941–1945)

II. 3. 1 Slovakia’s Declaration of War on America (1941)

II. 3. 2 At the Grave of Vančura (1942)

II. 3. 3 Hitler, Hlinka – One Line! (1942)

II. 3. 4 The Expulsion of the Czechs from the Slovak State (1943)

II. 3. 5 The Slovak Workers in Germany (1943–1944)

II. 3. 6 To the Slovak Women (1944)

II. 3. 7 The Attempt on Hitler’s Life (1944)

II. 3. 8 The Slovak National Uprising (1944)

II. 3. 9 About the Future (1945)

II. 3. 10 Banská Bystrica – Liberated! (1945)

III. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs (1945–1950)

III. 1 Assistant Secretary of State (1945–1948)

III. 1. 1 The Communist Coup d’Etat (25 February 1948)

III. 1. 2 The Yugoslav-Soviet Split (29 June 1948)

III. 1. 3 Czechoslovakia’s International Relations (1945)

III. 1. 4 On Money (1946)

III. 1. 5 Czechoslovakia’s New Foreign Policy (1947)

III. 1. 6 On Germany and the Marshall Plan (1947)

III. 1. 7 The Slovak-Hungarian Transfer of Population (1945–1949)

III. 2 Minister of Foreign Affairs (1948–1950)

III. 2. 1 The Mysterious Death of Jan Masaryk (1948)

III. 2. 2 Operation Balak (1948)

III. 2. 3 The UN Summit in New York (1949)

III. 3 The End (1950–1952)

III. 3. 1 Arrest and Interrogation (1951–1952)

III. 3. 2 Show Trial and Execution (1952)

III. 3. 3 Rehabilitation (1963–1968)

Conclusion – and a few questions

Oral History Interview with Mr Antonín Liehm (*1924)

Appendix

Clementis in Data

Chronology

Bibliography

Copyright

This study is dedicated to my former teachers Carsten Goehrke, Herrmann Lübbe and Georg Kohler.

I am immensely grateful to my Slovak and Czech friends and colleagues who taught me, from different political viewpoints, about Czechoslovakia’s Communist regime and how the rule of the proletariat affected their daily life. They are still teaching me.

Abbreviations

Archives and libraries

ABS USTRČRArchiv Bezpečnostných Sílů – Ústav pro Studium totalitních režimůČeské Republiky – Archives of the State Security Services at the Institute for the Study of Totalitarian Regimes of the Czech Republic, Prague.

AMZV ČRArchiv Ministerstva Zahraničnich Věcí České Republiky – Archive of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Czech Republic, Prague.

HÚ SAV Historický Ústav Slovenskej Akadamie Vied – Institute of History at the Slovak Academy of Sciences

SNA Slovenský Národný Archív, Bratislava – The Slovak National Archives, Bratislava, Slovak Republic.

SNK Slovenská Národná Knižnica, Martin – The Slovak National Library, Martin, Slovak Republic.

OF VCOsobní Fond Vladimír Clementis – Personal Fond Vladimír Clementis

USD AV ČR Ustav pro Soudobé Dějiny Akademie Věd České Republiky – Institute for Contemporary History at the Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic

Political parties, associations and organizations

COMECON Council for Mutual Economic Assistance; see RVHP

CP Communist Party

CPI Communist Party of Israel

ČSSD Česká Strana Sociálně Demokratická – Czech Social Democratic Party

ČT Česká Televize – Czech National TV

DS Demokratická Strana – Slovak Democratic Party

HG Hlinkova garda – Hlinka Guards

HSĽS Hlinkova Slovenská Ľudová Strana – Hlinka’s Slovak People’s Party

IDF Israel Defence Forces

IMRO Inner Macedonian Revolutionary Organization

KPSS Kommunističeskaia Partiia Sovetskogo Soiuza – Communist Party of the Soviet Union

KSČ Kommunistická Strana Československa – Czechoslovak Communist Party

KSS Kommunistická Strana Slovenska – Slovak Communist Party

MP Member of Parliament

MZV Ministerstvo Zahraničních Věcí – Czechoslovak Ministry of Foreign Affairs

NAM Non-Aligned Movement

NATO North Atlantic Treaty Organisation

NF Národní Fronta – National Front

NKVD Narodnii Kommissariat Vnutrënnikh Del – The People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs

OSS Office of Strategic Services, USA

RVHP Rada vzájomnej hospodárskej pomoci – Council for Mutual Economic Assistance

SPS Slovenský Poslanecký Klub – Slovak Parliamentarians Club

SĽS Slovenská Ľudová Strana – Slovak People’s Party

SNP Slovenské Národnie Povstanie – the Slovak National Uprising against Nazi Germany on 29 August 1944

SNR Slovenská Národná Ráda – Slovak National Council

SNS Slovenská Národná Strana – Slovak National Party

SSSR Soiuz Sovietskich Socialističeskych Respublik – Union of the Soviet Socialist Republics

StB Státní Bezpečnost – Czechoslovak State Security Service

STV Slovenská Televízia – Slovak National TV

UNRRA United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration

ÚV KSČ Ústředný výbor Kommunistická Strana Československa – Central Committee of the Czechoslovak Communist Party

ÚV KSS Ústředný výbor Kommunistická Strana Slovenska – Central Committee of the Slovak Communist Party

WJC World Jewish Congress

Acknowledgements

Writing the first political biography of Vladimír Clementis in English was a journey to the past, to my student years at the University of Zurich. In the early 1990s, I attended a seminar on East European History, focussing on the show trials in the Soviet satellite states. Carsten Goehrke was our professor, an excellent teacher.

We students wondered why stout Communists in Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Romania, Bulgaria and Poland, who had fought in the Spanish Civil War and survived Nazi concentration camps, would admit to crimes that, given their dedication to Marxism-Leninism, they could not possibly have committed. In the course of the seminar we realized that we too would have confessed, that everybody would confess if subject to that particular kind of physical and psychological torture.

Systematic deprivation of sleep, beatings, cold prison cells, the loss of one’s high position, the sorrows about one’s family, endless interrogations and, above all, the appeal to Party discipline. These methods destroyed the resilience and resistance of the fiercest believers in Marxism-Leninism, all of them in top Party and government positions at the time of arrest.

We students further learnt that the blueprints of the show trials in the satellite states had been drawn up in Moscow in the 1930s. The show trials of Grigorii I. Sinoviev (1883–1936), Lev B. Kamenev (1883–1936) and Nikolai I. Bukharin (1888–1938) enjoyed a brutal renaissance in Central and Eastern Europe, starting with the trial of László Rajk in Budapest in the autumn of 1949. In view of the emerging Cold War, the Soviet Union needed a disciplined bloc to be prepared for the fight against Western Capitalist Imperialism. The mastermind, whose shadow loomed over Prague in 1952, was Generalissimus Stalin. The Czechoslovak show trial focussed on the Czech Rudolf Slánský, the former General Secretary of the Czechoslovak Communist Party.

I was curious about the Slovak Communists, in particular, Vladimír Clementis, Foreign Minister and member of the Central Committee. In this volume, I tried to convey to the reader how the political history of Central Europe affected the life of a Slovak Communist, intellectual and politician. I tried to probe into Clementis’ thought and activities with a dispassionate and rational approach. The history of Czechoslovakia in the crucial years from 1945 to 1948 can teach us a lot about Realpolitik, political strategy in domestic and foreign affairs, psychology and lastly, the range of choices a Communist politician and diplomat had at his disposal.

Almost thirty years after the fall of Communism in Europe in 1989, there are still blank spots in the history of Slovak Communism. The Czechoslovak show trial of 1952 has been largely researched, but the Western reader is much more familiar with the fates of the Czech Communists. I hope that this biography will be helpful, especially for the younger generation that did not witness the Cold War, in understanding the Slovak part of Czechoslovak Communism with its distinct goals and plans, emblematically embodied in the fate of Clementis. Cicero was perfectly right in saying that history is magistra vitae, the grand teacher of mankind. Where else could we learn about politics than from history?

As a scholar specializing in Central European intellectual history, I want to understand how people thought in their particular historical context and why they acted the way they did. What motivated Clementis to join the Czechoslovak Communist Party as a law student at the prestigious Charles University in Prague, the capital of the only democracy in Central Europe in the interwar period? Why did he return to the Party after having broadcasted for the Beneš exile government in London during WWII? These are but two of the questions that have puzzled me over the last three years while writing this book.

My thanks: The Stiftung zur Förderung der wissenschaftlichen Forschung at the University of Zurich UZH granted me a generous stipend, which allowed me to do research in the archives. I am greatly indebted to my colleagues and friends for their interest in my research and willingness to discuss specific issues with me. In alphabetical order: Jozef Banáš, Juraj Benko, Valerián Bystrický (†), Zdenka Garnotová, Frank Grüner, Ivan Kamenec, Kristina Larischová, Hermann Lübbe, Adis Merdzanovic, Slavomír Michálek, Daniel E. Miller, Marie Neudorflová, Jan Pešek, Francis Raska, Dušan Šegeš, Nikola Todorović, Valentina Welser, and my friend XY, whose wish for anonymity I respect.

I thank the following persons for their professional, friendly, swift and uncomplicated assistance: Ľudmila Šimková and the ladies at the Slovak National Library (SNK) in Martin; Erika Javošová at the Slovak National Archives (SNA) in Bratislava; Markéta Kuncová and Michal Majak at the Archives of the Czech Foreign Ministry (AMZV) in Prague; Jitka Bílková, Veronika Chroma, Tereza Douchová, Zuzana Svobodová and Petr Zeman at the Archives of the State Security Forces at the Czech Institute for the Study of Totalitarian Regimes (ABS ÚSTRČR) in Prague and Lisa Brun at the Institute of Philosophy at UZH.

The ladies at the housing office of the Slovak Academy of Sciences have made my annual research stays since 2008 such a joyful and uncomplicated matter: Maria Vallová, Božena and Ľubica Konečná, thank you. Valerie Lange at ibidem publishers is an exceptionally patient, effective and supportive editor. Since the autumn of 2013, ibidem has a cooperation agreement with Columbia University Press. I thank Peter Thomas Hill for proofreading my manuscript and teaching me how to express myself in an elegant and scholarly English.

This study could not have been written without Vlasta Jaksicsová’s expertise. Vlasta was my supervisor for three years. She taught me how to look at Slovak history from the perspective of leftist intellectuals and artists. Born at the turn of the 20th century, they had a particular mindset: they had clear ideas, a holistic approach to the organization of social life. Although I focus on Clementis’ political thought, Vlasta’s advice was invaluable; thanks to her, I was able to understand Clementis’ mindset within the context of the leftist intellectuals in the first half of the 20th century.

Needless to say, any errors and shortcomings in this volume are my own.

Josette Baer

Zurich, Bratislava and Prague, March 2017

The Drama of Vladimír ClementisThe Tragic Life of a Communist

“We are all more like vast subterranean caverns, uncharted even by ourselves, than we are like holes dug straight into the ground. The urge to insist that the complex is just a disguise for the simple was one of the plagues of the twentieth century.”1

Timothy Snyder, 2010

“An emigrant without a home, yet everywhere at home, a cynical cosmopolitan with a secret longing, a perennial Jew by the waters of Babylon …2

When, at the beginning of WWII, Laco Novomeský wrote these sad words about Clementis’ brutal fate, he had no idea (or did he just have an inkling?) what tragic and bizarre end the lives of two communist intellectuals would meet after the war. Intellectuals who blindly believed (indeed, belief has to be blind) in a better world that would also be more just, by dint of critical thinking, sacrificed more than their personal freedom.

The sacrifice of Vladimír Clementis was a final one, the ultimate sacrifice. With regard to his biography and tragic end, known and documented by historiography, his sacrifice was for nothing, bereft of sense.

Clementis’ life that was so tightly connected with the trajectories of the development of Slovak society and the politics of the first half of the 20th century was neither exceptional nor original; it was the common life of a Slovak and Czechoslovak intellectual,trying to catch up with the life of Western intellectuals.

***

Was it ‘only’ duty born of fanatical conviction, which an engaging and disciplined communist ‘had’ to exercise in the times of European and national crisis? Did he have to fight not only Fascism after Hitler’s attack on the Soviet Union (!), but also follow ‘the party’s instructions’ (which he, from time to time, allowed himself to criticize) that demanded the active participation in the revolutionary change of the world?

Or was it just the task of a communist intellectual, cast in the eschatological and visionary belief in the historical inevitability of the global victory of the dictatorship of the proletariat? That one single ‘rational event in history’, according to Marx, that ‘pragmatic and successful’ event that Lenin’s communist party of Soviet Russia had been the first to realize, followed by Stalin in the Soviet Union?

Or was it the duty of a myopic politician, who, after his experience of the war and a brief ‘aberration’, acted, first, as secretary of state under Jan Masaryk and, after the communist coup d’état of February 1948, as Foreign Minister, supporting the establishment of communism inCzechoslovakia? Was he, after the victorious revolution, one of the Jacobin victims of the ‘war Diadochi’ and the powerful, intent on ‘settling old bills’?

Was he a perpetrator or a victim – or, according to Hannah Arendt, both? Was Clementis an intellectual or rather an ambitious man, eager to distinguish himself in politics at all costs?

Even if we have the impression that a part of the answer is already encoded in the questions, we shall find no satisfactory explanation, only a general one. All the more so, as we are, in Clementis’ case, confronted with a blend of biography and history. Nevertheless, I am trying to find answers, risking overgeneralization. Naturally, I am also aware that if a historian wants to understand and carefully and consistently interpret a distinct historical event, he or she has to ignore the framework of a single perspective and accept the validity of several. That is, to explain the phenomenon within the historical context and scrutinize the key factors. Yet, a historical essay, which this text aspires to be, has the advantage that it neither can nor has to stick to the scientific principles mentioned.

It seems to me that Vladimír Clementis (1902–1952), ‘a modern man of today’ who breathed in ‘the air of the new times’ with a vengeance, who, after WWI, got involved with the limits and stagnations of Slovak society, was no typical intellectual. There is no doubt that he fervently contributed to Slovak culture as an organizer and spokesman of the Davists, publishing uncountable texts and articles about literature and history in DAV, the journal of the Slovak leftist avantgarde. But he lacked the independent artistic-creative character trait that was so typical of the Slovak (and Czech) intellectuals of those times, most of them writers or poets. First and foremost, Clementis loved and promoted the arts, but he did not excel in any artistic activities. Yet, he did acknowledge his shortcomings (with a certain regret), not only in his Unfinished History. Because of his dominant personality, his psychological and professional skills, Clementis was much more of a ‘homo politicus’ than an artist.

***

To understand the origins of Clementis’ opinions and ideas, concepts and thoughts that usually originate in one’s youth, we ought to go back in history, not only to the historical events in Russia on the eve of WWI that became a kind of ‘certificate of baptism’ of the European leftist intellectuals. This was the generation born in 1900 to 1905: Jean-Paul Sartre, Arthur Koestler, George Orwell, Raymond Aron, Vítězslav Nezval, Jaroslav Seifert, Karel Teige, Ladislav Novomeský and others.

In intellectual terms, this young generation was clearly the most influential group in the 20th century. By inheriting and interpreting modernism, it tore itself away from religion and tried with great personal enthusiasm to think about the world and society as a complex of secular problems. The leftist avant-garde adopted Nietzsche’s ‘God is dead’, and the spiritual vacuum as its consequence replaced the Kantian ethical imperative one had hitherto had to obey in all decisions of a moral nature. Yet, the so-called socialist ethics that this generation tried to extract from Marx’s analysis of capitalism was both a relic and a replacement of religious authority,which Lenin, Marx’s successor, very quickly understood, presenting himself as a genius of Marxist dialectics.3

As a secular religion, Marxism could explain everything: not only was it political narrative, economic analysis and social critique, it was also a fundamental ‘theory of the universe’. And Lenin, the Bolshevik, the political strategist and master tactician, demonstrated his ‘genius’ with blending the secular religion of the progressive West with the backward East’s radicalism. To be a revolutionary Marxist meant that it was absolutely necessary to decide about the fate of others in the name of their own future. Clementis’ generation was fascinated (enchanted) by the revolution. The intellectuals thought of it as a distinct secret, a particular meaning, which they could hold on to, and so they kept justifying all sacrifices, mainly the sacrifices of others. In the spirit of Lenin’s ethically doubtful apologetics of “petty lies, frauds, betrayals or false pretences”, these sacrifices were morally legitimate in view of the honest goals of the Socialist future.4

That generation felt the attraction of Leninism already in the first years after the revolution; Leninism reached the peak of its attraction when Hitler assumed power, and the currents of history dragged and forced that generation willy-nilly to face the tragic issues of their times. If one did not make a personal choice of one’s party comrades, one’s co-travellers through time, one was not able to choose at all. And many of them, in particular Clementis, had chosen their comrades already in their early youth, although some who survived the human consequences of the theory changed their beliefs at a later point in time (André Gide or Arthur Koestler, but also the younger Albert Camus).

Clementis, however, did not question his beliefs. To tell the truth, he could not, because he fatally missed out on the three opportunities offered to him by life’s circumstances. First, at the end of the 1930s, he closed his eyes, ignoring the consequences of Stalin’s regime of terror – he neither wanted to nor could believe the news, since he was afraid (like so many of his comrades) of losing faith. Most probably, he dismissed his doubts (he talked about them with Ehrenburg) with the pseudo-powerful argumentation of the revolutionary: “The situation is difficult, we have to take serious decisions, we cannot renounce on violence, this is a revolution, after all” and “if you work in the forest, wood chips will fly”. The second opportunity presented itself at the beginning of WWII: certainly, Clementis openly criticized Hitler’s pact with Stalin and the latter’s aggressive foreign policy against unarmed Finland, but he did not draw the obvious conclusions – clearly, he could not bear the sad life of a refugee and the feeling of being excluded from the party that was like a family to him.

There is no doubt that one crucial principle had its validity also for Clementis:to be a communist in the 20th century meant to believe that there was no other purposeful way of life. He missed also thethird opportunity, which was no longer about waking up and seeing the reality, but the last chance to save his life. A few short days before the beginning of his fall, while he was attending a session of the UNO in the USA, he refused to believe a trustworthy source warning him that the comrades at home were preparing a trap for him. Much like in a classic Slovak fairy tale, fate did not bestow a fourth opportunity on him.

He failed as a politician, since he obviously could not adapt himself to Marx’s winged words, inspired by Machiavelli that “in politics, it is possible to connive even with the devil to reach a certain goal, but you should make sure that it is you who deceives the devil, not the other way round”.5 He failed also as an intellectual, because he forgot that in life, unlike politics, one’s personal truth has no influence on an unstable society. “To insist on more courageous and less transient principles … to give preference to doubt, to the relativism of tolerance, to scepticism … but with well-meaning resignation and the understanding that one cannot steer the political reality like a politician usually can …”6

***

The party the 23-year-old doctor of law joined in 1925 certainly stressed its adherence to Czechoslovakia with its name, Czechoslovak communist party,7 but it was the Communist International that directed it according to the spirit of Lenin’s words about “the necessity of the revolutionary struggle for socialism”. The goal of the International was to impose on their European political allies the principles and methods of the Russian Bolsheviks, the victorious comrades of the 1917 revolution. The European comrades should be reliable and trustworthy, defending “the interests of the first state of workers and peasants”.

In the spirit of their traditional conspirational attitude, the Soviet comrades prepared an overthrow in the Czechoslovak communist party; in 1929, they established a new leadership under Klement Gottwald, a man who lacked in education as much as in decent behaviour. Gottwald was hardly capable of pronouncing properly a word with four syllables (in phonetic Czech: demogratsie; in phonetical English: dimograsi). The new leadership adopted ‘democratic centralism’ as the strict Bolshevik principle of party work and thought like a cult, which alone knows what is right; its task was to convince the members of its principles or then, destroy them, because, from the viewpoint of the Russian Bolsheviks, this was the only way to achieve absolute political power. Twenty years later, Gottwald and his followers (Jan Šverma, Rudolf Slánský, Václav Kopecký, and others) would assume absolute power.

The conservative group of the old communist writers protested against the new leadership with the open letter of ‘seven’ writers, but together with ‘other communist artists of the younger generation’ the two Slovaks Clementis and Novomeský, already famous because of their activities for DAV, condemned the protest as a ‘grave mistake’. I think that this event, which was unique in the history of the communist movement, rendered problematic not only the ideological development of Czechoslovak communism, but also its historical assessment. Yet, in those years – and under the particular conditions pertaining in Czechoslovakia – the odd union of the Slovak Davists with the Czech non-conformist avant-garde (Teige, Nezval) and the Stalinist party leadership had its distinct logic. Apart from their age, these factions shared not only an unconditional admiration for the Soviet Union, a country “where tomorrow means already yesterday”; they also shared the view that political radicalism had to decide about the reality of society.

The European intellectual elite, hence also the Slovakand Czech avant-garde, was in awe of the young Soviet artists’ commitment to the revolution (Isaak Bábeľ, Vladimír Maiakovskii, Boris Pasternak, Sergei Eizenštein, Viacheslav Maierchold, Vladimír Tatlin and others); but they were not aware that the freedom of art was already gravely restricted. In the European artistic and intellectual circles of the mid-1930s, particularly in the French (Breton and the surrealists) tightly connected with Czech culture, the illusion still prevailed that the interaction of artistic freedom and political power was a distinct possibility. The rift between the party and the revolutionary intellectuals became visible only at the end of the 1930s as a consequence of the Moscow show trials and Stalin’s international diplomacy; this rift made the position of the European communist intellectuals in their anti-Fascist struggle more difficult, because it unsettled their unconditional belief in their ‘second home country’.

***

Leaving aside for a moment the perspective of the Czechoslovak state and the rather grave and fundamental ‘problems’ of the leftist avant-garde artists compelled to express the tone and direction of the modern national (Czech-dominated) culture, we find that the starting point of the Slovak communist intellectual (artist and functionary alike) was a particular one in the years of the First Republic. To the Slovak intellectual, the existential theme of political, societal and cultural activities, add to this also his personal positions, was the Slovak question, an issue that would soon turn into the fatal accusation of ‘Slovak bourgeois nationalism’. In these ‘accelerating’ times Slovakia, in search of her modern national and political face, was condemned to ‘all-national’ cooperation, especially in the cultural sphere, which did not reflect the actual political representation of Slovaks and Czechs. The moral and political goal of the union of both nations was a fundamental matter. The whole of Czechoslovak society and the entire spectrum of political parties were aware of it, the conservative right as much as the liberal centre and the left. Against the deepening differences in thinking about that cooperation, there was one principal opinion that united all national and political factions: any solution of the economic, political and cultural problems was existentially connected with the solution of the Slovak national question. And the Davists led by Clementis who had just left the first brief aberrations of sectarian proletkult thinking behind them, began to think against the canon of communist internationalism; they very well understood the challenging issue of Slovak equality within the common state.

In spite of the fact that Slovak historiography has sufficiently analysed the Davists’ significance for Slovak society, I would, nevertheless, like to draw the reader’s attention to the group’s quite successful attempts at integration into Slovak public life, especially in the areas of politics, society and culture. After the first sectarian episodes, the Davists (certainly with the political consent of the party leadership) destroyed the senseless party principle that demanded of its adherents to focus exclusively on their own thought; they opened the journal DAV also to other ideas, thoughts that sometimes went against the official party line. Clearly, the Davists were not afraid of open and sharp polemics. They understood very well that the journal was a platform, where they could present their opinions, influence not only their followers, but also convince their ideological adversaries of their arguments, and first and foremost, win the young generation of educated Slovaks.

They thus largely contributed to the entire spectre of Slovak cultural journals, among them the eminent revue Kultúra, the voice of the association of Holy Adalbert (spolok Svätého Vojtěcha). Against all odds, these passionate members of the leftist avant-garde were very successful in becoming a part of the consciousness of Slovak society. They were very active: they chaired student associations and played a significant role in organizing and conducting manifestations of an all-national character, for example the Convention of Slovak Youth in 1932 or the first Congress of Slovak Writers in 1936 (Clementis, Tido Jozef Gašpar and Milo Urban wrote the draft of the writers’ resolution). Their almost fanatical ethos gained them not only the sympathy of their generation and younger followers (for example, the ‘R–10’ group, the surrealists), who (as became very quickly evident) followed in their wake; they could also arouse the admiration of their intellectual adversaries. Although the Christian nationalists Gašpar and Urban refused to become what Clementis referred to as ‘a modern man of today’, both stated approvingly that nobody in the Slovak cultural sphere had such clear ideas about the rightfulness of their programmeas the leftist intellectual minority: “Whoever was searching for justice, disgusted with the hypocrites, egotists and moneychangers … could not help but admire and support them”, even if “one, owingto inner personal barriers, could not join them in their path”.8 The radical leftists had no hope of convincing the wider conservative Slovak society that only the socialist revolution and the dictatorship of the party could be a remedy of all problems. But they achieved a firm authority and an influence that could not be neglected, especially in the sphere of art and the organisation of cultural events. Particularly in the latter, they enjoyed the highest autonomy, because they were able to leave their own political dogma behind.

In the inter-war years, it seemed that the KSČ politically accepted the cultural activities of the Davists, who co-operated with the representatives of the right and the Catholic and nationalist cultural circles tightly or loosely connected to the Hlinka party. Yet, this radically changed after the war. Naturally, the events during the war contributed to that change, especially the different positions about the anti-Fascist resistance, which divided the home camp and the exile, including the communists in exile. After the war, the KSČ turned from an oppositional party into a state-building party; in view of its ambitions to centralize and embark on a struggle for power, the issue of Slovak autonomy became a burden, since the Slovak communists who had fought for it in the national uprising of 1944 refused to give it up. On the way towards a successful installation of its monopoly of power, the Prague party centre thus did not hesitate to sacrifice the Slovak communists.

***

The history of mankind is full of senseless human sacrifices and victims; why should the recent 20th century, a century with two world wars, violence and genocide, be different? The Stalinist show trials of the 1950s were a phenomenon hitherto unknown in European history and modern Slovak history alike. Because of the theatrical Asiatic perfidity that demonstrated the burial of law and human courage, psychiatrists are more capable of analysing the show trials as a morbid legacy of communism than historians. Fifty years of lawlessness, political trials and organised violence in the communist part of Europe, leniently referred to as the era of ‘personality cult’ were, however, only a kind of a ‘déjà vu’ of what had happened in the Soviet Union in the 1930s, when Stalinism established itself as a system of power.

The 1930s was a point of reference, the neuralgic point and magic circle alike, around which the majority of the leftist intellectuals of those times moved, incapable of tearing down that fatal web. And the majority of them, starting with the French communists (and the non-communists) and ending with our home grown epigones, did not even come to their senses when our own party members, especially Clementis, stood in the dock. Had they learned nothing? Had they not read Gide’s Return from the USSR and Afterthoughts on my Return from the USSR (1937)? After all, newspapers and journals of the entire political spectrum commented about Gide’s Return (1936). What did they think of the words of František X. Šalda, a respected humanist and intellectual authority? Šalda had written that “the trial turned the stomach of the more decent Europe”, while“in the Czech lands (and also in Slovakia – VJ) one remained silent, because it is opportune to keep quiet about Russian matters and because we are a country of oppressed dwarfs; nobody wants to get his fingers burnt”.9 No Slovak leftist intellectual joined in to support Teige’s revolt against Stalin.

Yet, the thought that Clementis stopped the publication of DAV in 1937 so that he would not have to react to the Stalinist purges, is a very likely explanation. The question, however, is: how would he have reacted – would he have toed the party line or stood up against the party, demonstrating that he was a learned man, a man of culture? Again, we can find an answer only from a general perspective.

For those who believed in the country that was realizing the utopia, the Soviet events had no influence on what they saw with their own eyes or how they immediately experienced the reality of a life under Bolshevism. Those who went there with burning belief, Clementis among them, usually returned in the same state of mind; only André Gide was a famous and remarkable exception. Clementis, the future Slovak ‘advocate of the poor’, lover of the arts and social life, missed in Moscow, just so, the coffee houses: “To a Central European, it is a somewhat strange feeling ploughing through the city all day and not being able to leave one’s tracks to jump to the next coffee house for a break.”10 True, this dedicated disciple of communism did not look for an assessment of the current reality, but for the future successes of communism as the only criterion of judgement.

Moreover, in terms of the show trials of 1936, there was no historical precedent, no example from history that would have prompted understanding of the significance of these events and the deeper sense of Stalin’s enterprise.To any contemporary person living in a European liberal democracy (with the exception of the French intellectuals who conceived of them as terror regime of Robespierrian proportions), it was simply inconceivable that people would confess to terrible crimes if the accusations did not bear some truth.11 At the end of the 1930s, the communist intellectual (and the decent non-communist intellectual alike) had a higher purpose to keep quiet – the logics of anti-Fascism: any open criticism of Stalinism would have weakened the only faction that fought against Fascism. That was the reason why it was so hard for Clementis to criticise Stalin.

With the historic and political events of 1938 inundating Europe, the Moscow show trials ceased to be the focus of international attention. During the following years of the terrible war, when Europeans fought for the survival of their civilisation, the ‘dust’ of benign forgetting began to cover their historical memory. In 1945, immediately after the end of the war, there was neither purpose nor political will to remember, to go back to the Moscow trials of the 1930s. Yet, only three (!) years after the war, the ‘spirit’ of the trials came alive in Czechoslovakia, in the historic reality after the Communist coup d’état of 25 February 1948.

***

One cannot understand this shameful ‘episode’ of recent history by simply tearing it away from its historical trajectory and studying it in isolation. It can only be understood in the context of the war and immediate post-war Europe, as the British historian Keith Lowe so superbly showed in his myth-destroying volume Savage Continent, a shocking portrait of chaos,lawlessness and terror. The famous Czech writer Ivan Klíma: “War destroys everything, not only human lives, not only houses, churches and factories, but also something delicate that can live only in times of peace: we may call it law, culture or just the ability to uphold the respect for human life.”12

Yet, as fervently as the post-war wave of violence countered the previous wave of violence, there was nothing left to counter after the February coup d’état. Or, was there, just about? As well as victors, every revolution also has its losers and, even if the latter are in the majority, they have to be punished with violence, silenced with fear. Therefore, the unsuccessful got even with the successful; the uneducated and half-educated with the educated and the cowards with the courageous. And finally, every revolution offers the masses material and spiritual opportunities to act: it demands the humiliation of all who have put themselves above it. It claims that the revolutionaries act in the service of some higher historical justice, in the name of progress, for the good of all “and the people, that undefined but artificallyprojected entity”.13

***

In modern times, too many educated people served a fanatical idea opposed to everything mankind had so far achieved; these persons betrayed everything that bound them to their knowledge and profession. The mass failure of the intellectuals (especially those, who did not directly participate in the execution of totalitarian power, but spoke out in favour of it or tolerated it) is a simple historical fact many researchers have been occupied with for decades. There is no doubt that one requires significant moral strength to resist the pressure of a totalitarian regime. The failure of many intellectuals in the countries controlled by the communists cannot be excused, but one can at least explain it. However, the thought of intellectuals who, over mass graves, lost themselves in revolutionary ideologies while enjoying the liberty of their democratic countries, completely defies understanding. This mindset is absurdity in perfection. Lenin might have thought exactly of this kind of intellectual when he spoke of “useful idiots”.

When Jean-Paul Sartre visited Czechoslovakia in 1963 with his partner Simone de Beauvoir, he declared in a discussion with Czech and Slovak intellectuals who considered him an icon of philosophy and literature that “to him, the perfect humanist was the hero, who, in spite of all the terrible experiences, remained a socialist”.14 Sartre stressed that he spoke of those who had survived the Stalinist prisons and were still communists. Soon after, the writer was awarded the Nobel Prize (which he refused); a further statement of his is worthy of remembering: “The only really great novel that can be written in this century is a novel about the socialist experience.”15 And the great writer justified his big illusion in front of a public that was surviving that ‘experience’ first-hand and regarded contemporary socialism as a pointless error of history: “Socialism, whether it has a future or not, is moulding the mind of our entire epoch, it might be hell, but hell too can be a subject for literature – disappointed hopes, the deaths of comrades – is this not the most modern perfection of tragedy?” By no means few of the shocked listeners might have thought exactly the same as the writer Ivan Klíma: “Hell is a great subject, as long as one doesn’t have to live in it.”16

***

The 20th century was the era of the intellectuals with all the concomitant betrayals, resignations and compromises. The story of the European leftist intellectual, the first and also the last educated man in modern history organized in a group, came, after a brief revival at the end of the 1960s, to an end. He was simply no longer needed nor taken seriously, because, after the experience with communism in practice, the world no longer believed in any kind of paradise on earth; that is why the search for a solution by universally valid ideologies ceased to exist. The last generation of the radical communists of the 1960s disbanded. Even if some individuals turned for a brief time to Maoism or Fidel Castro, the major part of the Western European leftist intellectuals either joined the right or shut themselves away in postmodern discourses (individual or group rights, the horrors of globlization etc.) And, until the very end in 1989, the East European intellectual (especially the Czech and Slovak) looked with disgust at the twenty-year regime of socialism in practice that was realizing the communist ideals. In terms of political culture, Marxism became a marginal phenomenon; in the 1970s, it retired to the universities and academies, where it slowly withered away.

Bratislava, January 2017

Vlasta Jaksicsová

1Thinking the Twentieth Century. Tony Judt with Timothy Snyder (New York: Penguin, 2013), xiii. The Czech edition: Intelektuál ve dvacátém století. Rozhovor Timothyho Snydera s Tonym Judtom (Praha: Prostor 2013), 17.

2 Ladislav Novomeský, “Aký si (How you are)”, from the collection Svätý za dedinou (Patron Saints for the Country) (1939) (Bratislava:Literárne informačné centrum, 2005). Novomeský dedicated the poemto his friend Clementis; the collection was a hommage to the past of the 1930s.

3 Jaksicsová, “Intelektuál ve …”, 97.

4 Jaksicsová, “Intelektuál ve …”, 106.

5 Karel Kosík, “Iluse a realismus”, Listy, no. 1, 7 November 1968, quoted after Milan Jungmann, Literárky můj osud. Kritické návraty ke kultuře padesátých a šedesátých let s akuálními reflexemi (Praha: Atlantis, 1999), 300.

6 “Úvodník”, Listy, no. 15, 17 April 1969, 312-313.

7 The KSČ emerged in 1921 in the traditional way by splitting from the Social Democrats. Both parties enjoyed legal recognition and participated in the Czechoslovak parliamentary life of the First Republic. In the tradition of the European Socialists, Bohumír Šmeral, the chairman of the Czech communists, believed that Socialism would win by parliamentary means.

8 Milo Urban, Kade-tade po Halinde. Neveselé spomienky na veselé roky (Bratislava: Slovenský spisovateľ, 1992), 261. Milo Urban would become a principal representative of the clerical-fascist Slovak state in 1939. His mentioning of ‘moneychangers’ was not only an antisemitic remark, but also a critique of the representatives of big business, to whom money was everything and culture a negligible area.

9 František Xaver Šalda, “Gidovo zklamání ze Sovětskeho Ruska”, Zápisník IX (1936-1937): 109-120.

10 Vladimír Clementis, “V centre päťročnice”, in Vzduch našich čias. Články, state, prejavy, polemiky 1922-1934, vol. I (Bratislava: Vydavateľstvo politickej literatúry, 1967), 179.

11 Jaksicsová, “Intelektuál ve …”, 189, 199, 201.

12 Ivan Klíma, Moje šílené století I (Praha: Academia 2009), 345.

13 Klíma, 130.

14 Klíma, 448.

15 “Sartre a de Beauvoir v Bratislave”, Kritika & Kontext VII, no 1 (2002): 17.

16 Klíma, 448, 449.

X. Introduction

X. 1 Vladimír Clementis – victim of Stalinism or gravedigger of democracy?1

“I entered the Minister’s office with Vavro Hajdu. Clementis had not heard us knock and was standing by the window, cautiously raising the curtain and looking out into the street. He was nervous and worried. He told us that an additional group of men from the Security Services had been added to his bodyguard that morning. […] I saw Clementis several times since he continued to live in the Ministry apartment, while his new flat was being decorated by the Ministry of the Interior. I had become particularly sensitive to the police methods in use so I concluded that security agents were installing microphones in his apartment to increase surveillance. When I saw him for the last time we merely hinted at it; he had the same suspicions as I.”2

Artur London (1915–1986), born into a Jewish Communist worker’s family from Ostrava in Moravia, remembered how the 1952 show trial of the former General Secretary of the KSČ Rudolf Slánský (1901–1952) and fellow accused was being prepared in 1950. London had been the Deputy Minister of foreign affairs, Vladimír Clementis his boss. Of the fourteen high-ranking Party members accused, only London, Vavro Hajdu and Evžen (Eugen) Löbl (1907–1987) survived – they received life sentences. London was released from prison on 2 February 1956 and officially rehabilitated by Prime Minister Viliam Široký (1902–1971) on 14 April 1956.

Clementis, Slánský and nine other Party members3 were sentenced to death for their betrayal of Communist Czechoslovakia, charged with Titoism, Zionism, conspiracy, sabotage and espionage on the payroll of Western Capitalist Imperialism. The eleven sentenced were hanged on 3 December 1952, one after the other, starting at three o’clock in the morning. Clementis died at five o’clock. Who was Vladimír Clementis? I think that there are three ways to address this question.

First, from a democratic viewpoint that opposes totalitarian rule, in particular the Nazi regime and the Marxist-Leninist regimes in Central Europe in the 20th century, one could describe Clementis as a champagne communist: he had a doctorate in law from the prestigious Charles University in Prague, loved good food, the arts, literature and enjoyed wearing expensive suits, sporting elegant pipes. He had joined the Party as a privileged student of law in Prague in 1925, despising the liberal atmosphere of the First Republic. He had had only contempt for the democratic values of the state Tomáš G. Masaryk (1850–1937)4 had established on 28 October 1918 after four tireless years of lobbying in France, Great Britain and the USA.

Clementis represented the KSČ’s interests in the Czechoslovak parliament, enjoying the democratic liberties bestowed on the members of parliament (MPs) by the very political system he wanted to abolish. After the Munich Agreement of 1938, he and his wife Lída left Bratislava for Prague. The Germans forced Slovak President Jozef Tiso (1887–1947) to declare Slovakia’s sovereignty in March 1939, and occupied the Czech lands, establishing the Reichsprotektorat Böhmen und Mähren. Clementis fled to Paris and thence to London, where he worked for the exile government of President Edvard Beneš (1884–1948).5 Resistance fighters of many nationalities, the majority of them Slovaks, lost their lives in the Slovak National Uprising (Slovenské Národní Povstanie, SNP) of 1944,6 fighting the Germans and the troops of the clerical-fascist Tiso regime, while the Czechs were suffering under brutal Nazi rule in the protectorate.7

Clementis, however, had a cushy job in safe London, broadcasting with the BBC for the exile government. Appointed assistant secretary of state (deputy foreign minister) in 1945 and foreign minister after the mysterious death of Jan Masaryk (1886–1948) on 10 March 1948, he faithfully served the KSČ, led by Klement Gottwald (1896–1953). In the mindset of a vengeful democrat, Clementis eventually got what he deserved, much like the sorcerer’s apprentice in Goethe’s famous poem: Spirits that I’ve cited / My commands ignore.8 His fate was poetic justice par excellence and bitter proof of how the Communists thanked their members: the Party he had been so eager to serve not only stripped him of his political power and ruined his reputation in the show trial, but sentenced him to death, and the fact that he was utterly innocent was but the perfect icing on the cake – Schadenfreude.

A second interpretation is basedon a principal understanding of the idealistic appeal and political attraction Marxism-Leninism9 had had for intellectuals in the first half of the 20th century. Like so many intellectuals all over the world, Clementis sincerely believed that Socialism would change the world and humanity for the better, bestowing justice on the oppressed workers. His criticism of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact of 1939 resulted in his expulsion from the Party while in exile. During the war, Communists from a proper proletarian background, that is, the working class, such as Alexander Dubček (1921–1992), who would be elected general secretary of the KSČ in January 1968,10 and non-Communists alike were fighting the Germans in the Eastern Slovak Tatra mountains, while Clementis was contributing to the war effort with his radio broadcasts from London, instilling hope and strengthening morale at home.

In 1945, the KSČ rehabilitated him, restoring his membership because of his talent for strategic thinking, brilliant rhetoric and unremitting loyalty to Marxism-Leninism. He was the only Slovak fluent in the languages of the Allies: he spoke French, English, German, Hungarian and Russian. The comrades in the Slovak National Council (SNR) suggested appointing him assistant secretary of state, because he had worked with the Beneš government in exile and had always spoken out for an equal standing of the Slovaks with the Czechs in the post-war Republic.

By 25 February 1948, the KSČ was in control of the country, referred to as the “victorious February” (vítězní únor).11 Clementis’ political career blossomed. In 1952, he was one of those accused of high treason in the Stalinist show trial of Slánský et al. and executed. But four years later, the political tides turned again: in his secret speech to the 20th Congress of the Soviet Communist Party on 25 February 1956, General Secretary Nikita S. Chruščev (1894–1971) revealed Stalin’s crimes, which prompted the thaw, the short-term liberalization in domestic affairs of the bloc states and Soviet relations with the principal class enemy USA. In Marxist-Leninist terms, the Stalin cult and the crimes and purges committed under the reign of the velikii vožd (the Great Leader Stalin) had been a subjective aberration, a mistaken interpretation of the legacy of Marx and Lenin. In its perennial wisdom, the KSČ understood the objective signs of the times, the need for social, political and economic reforms. Because of General Secretary Antonín Novotný’s (1904–1975) ideological intransingence, Czechoslovakia did not de-stalinize until the early 1960s. Novotný ruled the country with an iron fist. The KSČ embarked on a reform course only in January 1968, when even the loyal StB had had enough of Novotný, who was driving a wedge between the Slovaks and the Czechs, endangering the unity of the state and the people. The CC voted Novotný out and appointed Dubček head of state and party.

Had the show trial of 1952 not happened and Clementis not been executed, he might have been elected Deputy General Secretary to Slánský after Gottwald’s death in 1953 and steered the country onto a reform course. He might have, and this is, of course, speculation, established a Czecho-Slovak federation with the support of reform-minded Slovak and Czech comrades. With Clementis as a powerful Slovak voice in the CC KSČ, the much-needed economic and political reforms might have begun already in 1953, after Stalin and Gottwald’s deaths. The Prague Spring thus might not have happened with the vehemence it did under Dubček – and spared the country the invasion of Warsaw Pact troops on 21 August 1968 and the Soviet occupation that would end in 1990.

A third viewpoint is a combination of the first and second. I am an ardent defender of modern liberal democracy and Capitalist market economy, but I also understand why Marxism-Leninism was so attractive a choice in the first half of the 20th century, not only to intellectuals and academically trained professionals, but also to the agricultural workers in Slovakia. I shall attempt to present a fair and balanced interpretation of Clementis’ political thought, rendered vibrant in his articles, speeches for the BBC in exile and the unfinished memoirs his wife Lída (*1910–??) published in 1964, after the accused of the show trial were rehabilitated in 1963.12 The source material I found in the archives in Bratislava, Martin and Prague is available to the English reader for the first time.

I want to find out who Clementis was as a person and understand his reasoning, ideas and political motivation on the background of the historical context. My aim is to present a comprehensive portrait of a politician, diplomat and thinker, who was of crucial importance for his country’s politics before, during and after WWII. Clementis has been undeservedly forgotten by European history; the intention of this volume is thus to bring him back to the European historical memory – and with him, an insight into Slovak politics in the 20th century.

Communism in Czechoslovakia collapsed in November 1989 with the VelvetRevolution; the Cold War ceased to exist in 1991 with the dissolution of the Warsaw Pact. On 1 January 1993, Slovakia became a sovereign state, in spite of the fact that the dissolution, also referred to as Velvet Divorce, was a violation of the Czechoslovak Federal Constitution.13 The Velvet Divorceended the Czechoslovak Federation (ČSFR), and the Czech and Slovak Republics became sovereign states.14 The Slovak Republic joined NATO and the EU in 2004. Twenty-five years after the collapse of Communism in Europe, it is high time for a critical biography of Clementis, who was a loyal Party member, a talented lawyer and gifted intellectual. Whether one agrees with his unremitting belief in Marxism-Leninism or not, there is no doubt that Clementis was a crucially important politician for the Slovaks.

Why is this study the first biography of Clementis in English? I think there are two reasons: first, he was a Communist, dedicated to the ideals of Marxism-Leninism, the West’s principal theoretical adversary during the Cold War. The Marxist-Leninist system in Europe, save for Belarus that is being governed by what one could call a neo-Soviet regime, is de facto and de jure a thing of the past. Second, international academe is still largely ignoring Slovak history and historiography, mainly because regrettably few excellent Slovak historical studies are available in a world language such as English, French or German. Therefore, a biography that scrutinizes the political circumstances and conditions Clementis faced and acted upon should also be understood as a contribution to the history of Central European political thought in the first half of the 20th century.

The scientific literature about Clementis in Slovak is modest, in Czech non-existent. The principal study in English15 about the show trial of 1952 focuses on the former General Secretary Slánský, mentioning Clementis briefly in connection with the charges brought against Gustáv Husák (1913–1991) and Laco Novomeský (1904–1976), the most prominent Party members accused of ‘Slovak bourgeois nationalism’.16

There are only four Slovak studies analysing Clementis’ political thought and activities: Holotíková and Plevza17 published their superb biography in the liberal atmosphere of the Prague Spring in 1968. Drug’s study is an informative compilation of Clementis’ journalism.18 Čierny scrutinizes Clementis’ diplomatic efforts and political positions at the Czechoslovak Foreign Ministry after 1945.19 To honour the acting Assistant Secretary of State (Deputy Foreign Minister), the Czechoslovak publisher Obroda issued a collection of Clementis’ London broadcasts in 1947.20In 1967, Holotíková published a collection of his articles, speeches and interpellations in parliament, covering the years 1922 to 1938 in two volumes.21 An anthology summarizes the contributions to the scientific conference about Clementis that took place in May 2002, organized jointly by the Foreign Ministry of the Slovak Republic and the Slovak Institute for International Studies in May 2002.22 In 2012, a conference remembered Clementis as a patriot and European;23 a compilation of his memoirs and letters was published in 1998.24 A brief summary of Clementis’ life appeared in 2002.25

X. 2 Analytical framework and conceptual matrix

The biography of a politician who had held executive functions in Party and state should include various aspects: negotiations and decision-making in his functions as MP, assistant secretary of state, foreign minister and member of the CC of the KSČ; relations to domestic politicians, parties and interest groups; foreign policy strategy; analysis of the international situation; personal allegiances, political friends and adversaries; relations to Czech and Slovak exile communities abroad; relations to the country’s ethnic and political minorities; strategies on economic, education and social policy, to name but the most common ones. This biography cannot cover all these aspects.

I shall focus on two principal aspects of Clementis’ thought and activities: first, an analysis of his ideas about domestic politics, in particularSlovakia’s status in the common state. Second, an analysis of his ideas about Czechoslovakia’s foreign policy in the post-war years, in particular, Communist Czechoslovakia’s position and role as a member of the Soviet bloc in Europe and thus the country’s relations with the West.

This biography consists of three chapters: chapter I introduces the reader to Clementis’ childhood, upbringing, and early political activities, especially his journalism for DAV. In chapter II, I present his political activities in exile in France and Great Britain during WWII. Chapter III is dedicated to his last years, when his political career reached its peak. In chapter III, I present his arrest, interrogation, the show trial and, lastly, his rehabilitation in the early 1960s. In the conclusion, I shall try to answer my research questions, see below.

Analytical framework

My analysis of Clementis’political ideas and decisions unfolds in selected areas of Czechoslovak domestic politics in the years of the First Republic (1918–1938) and Czechoslovakia’s foreign policy from 1945 until his fall from grace in 1950. To assume that political thought or political ideas per se prompt immediate political decision-making would be overly idealistic. From 1948 on, several factors determined Czechoslovakia’s domestic and international affairs; these factors were crucially different from the country’s affairs in the three brief years of the guided democracy of the National Front (Národná fronta) from 1945 to 1948. The establishment of the Stalinist system on 25 February 1948 came along with the re-building and centralization of governmental and state institutions according to the Soviet model.

Conceptual matrix

The aim of the following questions is to guide the reader through the analysis; they represent a conceptual matrix that is divided into two parts, the first one focussing on Clementis’ political thought and, the second one, on his political goals. The conceptual matrix serves as a guideline for the reader to orientate himself.

Political thought, key concepts: national identity, political identity, Czechoslovakism, Realism, Socialism, Constitutionalism. What political arguments did Clementis use to legitimate his political goals? Which thinkers or philosophers inspired him? If he referred to Western thinkers, how did he apply their ideas to the social and economic conditions in Slovakia? Did he develop his own ideas about politics? How did he conceive of the Slovak autonomy movement led by Andrej Hlinka and the Slovak People’s Party? Why was Liberalism not a political option for Slovakia? How did he reconcile his belief in Socialism with working for the centre-right exile government, the class enemy? Why, in 1945, did he join the KSČ that had expelled him for failure to toe the party line in 1939?

Political goals, key concepts: rule of law state, minority rights, foreign policy, Slovakia’s status within Czechoslovakia, relations with the Soviet Union, Great Britain, France and the USA. What political goals, long-term and short-term, did Clementis pursue? What was the constitutional status of Slovakia that he projected as an MP in the First Republic and after WWII?

X. 3 Method, key issues, research interest

X. 3. 1 Method: contextual biography

This study has an interdisciplinary focus: it presents an analysis of political ideas on the background of established historical facts. My aim is to contribute to the research on the history of Central European thought. The combination of political theory analysis with contextual biography26 is particularly suitable for Clementis’ biography since it is based on a specific approach to biographical and historical writing. The contextual biography method offers us a deeper insight into the historical context, presupposing that a person’s activities, thoughts and personal impressions cannot be separated from the historical circumstances he or she was subject to. The British historian Sir Ian Kershaw, an FBA (Fellow of the British Academy), on the method and its relevance:

“Any attempt to incorporate such themes [technology, demography, prosperity, democratization, ecology, political violence, add. JB] in a history of twentieth-century Europe would not by-pass the role of key individualswho helped to shape the epoch. […] They are neither their prime cause nor their inevitable consequence.New biographical approaches, which recognize this are desirable, even necessary. Their value will be, however, in using biography as a prism on wider issues of historical understanding and not in a narrow focus on private life and personality.”27

The method of contextual biography and the analysis of political thought as a dimension of biographical writing present an interdisciplinary approach that affords a unique insight into Slovakia and Czechoslovakia’s political environment: Clementis’ descriptions and personal views render vibrant the historical context in which he thought and acted. His ideas and thoughts open up a prism on the intellectual atmosphere in the first half of the 20th century in Czechoslovakia. Clementis adhered to the Leninist principle that a Communist is allowed to think on his own, that the Party, within the confines of the theory and practice of the revolutionary road to Socialism, is tolerant of its members’ differing views and opinions.