Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Crossway

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Serie: Theologians on the Christian Life

- Sprache: Englisch

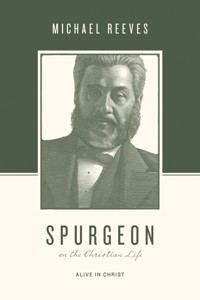

Charles Spurgeon, widely hailed as the "Prince of Preachers," is well known for his powerful preaching, gifted mind, and compelling personality. Over the course of nearly four decades at London's famous New Park Street Chapel and Metropolitan Tabernacle, Spurgeon preached and penned words that continue to resonate with God's people today. Organized around the main beliefs that undergirded his ministry—the centrality of Christ, the importance of the new birth, the indwelling of the Spirit, and the necessity of the Bible—this introduction to Spurgeon's life and thought will challenge readers to live their lives for the glory of God. Part of the Theologians on the Christian Life series.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 328

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

THEOLOGIANS ON THE CHRISTIAN LIFE

EDITED BY STEPHEN J. NICHOLS AND JUSTIN TAYLOR

Augustine on the Christian Life:

Transformed by the Power of God,

Gerald Bray

Bavinck on the Christian Life:

Following Jesus in Faithful Service,

John Bolt

Bonhoeffer on the Christian Life:

From the Cross, for the World,

Stephen J. Nichols

Calvin on the Christian Life:

Glorifying and Enjoying God Forever,

Michael Horton

Edwards on the Christian Life:

Alive to the Beauty of God,

Dane C. Ortlund

Luther on the Christian Life:

Cross and Freedom,

Carl R. Trueman

Newton on the Christian Life:

To Live Is Christ,

Tony Reinke

Owen on the Christian Life:

Living for the Glory of God in Christ,

Matthew Barrett and Michael A. G. Haykin

Packer on the Christian Life:

Knowing God in Christ, Walking by the Spirit,

Sam Storms

Schaeffer on the Christian Life:

Countercultural Spirituality,

William Edgar

Spurgeon on the Christian Life:

Alive in Christ,

Michael Reeves

Warfield on the Christian Life:

Living in Light of the Gospel,

Fred G. Zaspel

Wesley on the Christian Life:

The Heart Renewed in Love,

Fred Sanders

Spurgeon on the Christian Life: Alive in Christ

Copyright © 2018 by Michael Reeves

Published by Crossway1300 Crescent StreetWheaton, Illinois 60187

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher, except as provided for by USA copyright law. Crossway® is a registered trademark in the United States of America.

Cover design: Josh Dennis

Cover image: Richard Solomon Artists, Mark Summers

First printing 2018

Printed in the United States of America

Unless otherwise indicated, the author’s Scripture quotations are from the ESV® Bible (The Holy Bible, English Standard Version®), copyright © 2001 by Crossway, a publishing ministry of Good News Publishers. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

Scripture quotations marked KJV are from the King James Version of the Bible.

Emphases in Scripture quotations have been added by the author.

Trade paperback ISBN: 978-1-4335-4387-6 ePub ISBN: 978-1-4335-4390-6 PDF ISBN: 978-1-4335-4388-3 Mobipocket ISBN: 978-1-4335-4389-0

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Reeves, Michael (Michael Richard Ewert), author.

Title: Spurgeon on the Christian life: alive in Christ / Michael Reeves.

Description: Wheaton: Crossway, 2018. | Series: Theologians on the Christian life | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017026030 (print) | LCCN 2017032366 (ebook) | ISBN 9781433543883 (pdf) | ISBN 9781433543890 (mobi) | ISBN 9781433543906 (epub) | ISBN 9781433543876 (tp)

Subjects: LCSH: Spurgeon, C. H. (Charles Haddon), 1834–1892.

Classification: LCC BX6495.S7 (ebook) | LCC BX6495.S7 R44 2017 (print) | DDC 286/.1092 [B] —dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017026030

Crossway is a publishing ministry of Good News Publishers.

For John and Joan,

with deepest love and gratitude

for the best gift I have on earth

CONTENTS

Cover PageTHEOLOGIANS ON THE CHRISTIAN LIFETitle PageCopyrightDedicationSeries PrefaceAbbreviationsIntroductionPART 1CHARLES SPURGEON1A Man Full of LifePART 2CHRIST THE CENTER2Christ and the Bible3Puritanism, Calvinism, and Christ4Christ and PreachingPART 3THE NEW BIRTH5New Birth and Baptism6Human Sin and God’s Grace7The Cross and New BirthPART 4THE NEW LIFE8The Holy Spirit and Sanctification9Prayer10The Pilgrim Army11Suffering and Depression12Final GloryGeneral IndexScripture IndexBack CoverSERIES PREFACE

Some might call us spoiled. We live in an era of significant and substantial resources for Christians on living the Christian life. We have ready access to books, DVD series, online material, seminars—all in the interest of encouraging us in our daily walk with Christ. The laity, the people in the pew, have access to more information than scholars dreamed of having in previous centuries.

Yet, for all our abundance of resources, we also lack something. We tend to lack the perspectives from the past, perspectives from a different time and place than our own. To put the matter differently, we have so many riches in our current horizon that we tend not to look to the horizons of the past.

That is unfortunate, especially when it comes to learning about and practicing discipleship. It’s like owning a mansion and choosing to live in only one room. This series invites you to explore the other rooms.

As we go exploring, we will visit places and times different from our own. We will see different models, approaches, and emphases. This series does not intend for these models to be copied uncritically, and it certainly does not intend to put these figures from the past high upon a pedestal like some race of super-Christians. This series intends, however, to help us in the present listen to the past. We believe there is wisdom in the past twenty centuries of the church, wisdom for living the Christian life.

Stephen J. Nichols and Justin Taylor

ABBREVIATIONS

ARM

C. H. Spurgeon, An All-Round Ministry: Addresses to Ministers and Students (London: Passmore & Alabaster, 1900)

Autobiog., 1

C. H. Spurgeon’s Autobiography, Compiled from His Diary, Letters, and Records, by His Wife and His Private Secretary, 1834–1854, vol. 1 (Chicago: Curts & Jennings, 1898)

Autobiog., 2

C. H. Spurgeon’s Autobiography, Compiled from His Diary, Letters, and Records, by His Wife and His Private Secretary, 1854–1860, vol. 2 (New York: Fleming H. Revell, 1899)

Autobiog., 3

C. H. Spurgeon’s Autobiography, Compiled from His Diary, Letters, and Records, by His Wife and His Private Secretary, 1856–1878, vol. 3 (Chicago: Curts & Jennings, 1899)

Autobiog., 4

C. H. Spurgeon’s Autobiography, Compiled from His Diary, Letters, and Records, by His Wife and His Private Secretary, 1878–1892, vol. 4 (New York: Fleming H. Revell, 1900)

Lectures, 1

C. H. Spurgeon, Lectures to My Students, vol. 1, A Selection from Addresses Delivered to the Students of the Pastors’ College, Metropolitan Tabernacle (London: Passmore & Alabaster, 1875)

Lectures, 2

C. H. Spurgeon, Lectures to My Students, vol. 2, Addresses Delivered to the Students of the Pastors’ College, Metropolitan Tabernacle (New York: Robert Carter and Brothers, 1889)

Lectures, 3

C. H. Spurgeon, Lectures to My Students, vol. 3, The Art of Illustration; Addresses Delivered to the Students of the Pastors’ College, Metropolitan Tabernacle (London: Passmore & Alabaster, 1905)

Lectures, 4

C. H. Spurgeon, Lectures to My Students, vol. 4, Commenting and Commentaries; Lectures Addressed to the Students of the Pastors’ College, Metropolitan Tabernacle (New York: Sheldon & Co., 1876)

MTP

C. H. Spurgeon, The Metropolitan Tabernacle Pulpit Sermons, 63 vols. (London: Passmore & Alabaster, 1855–1917)

NPSP

C. H. Spurgeon, The New Park Street Pulpit Sermons, 6 vols. (London: Passmore & Alabaster, 1855–1860)

S&T [year]

C. H. Spurgeon, The Sword and Trowel (London: Passmore & Alabaster, 1865–1891)

INTRODUCTION

Crowds lined the streets, hoping to catch a glimpse of the olivewood casket as it made its way through the streets of south London. On top was a large pulpit Bible opened at Isaiah 45:22: “Look unto Me, and be ye saved, all the ends of the earth.” It was Thursday, February 11, 1892, and the body of Charles Haddon Spurgeon was being taken for burial. Eighteen years before, Spurgeon had imagined the scene from his pulpit:

In a little while, there will be a concourse of persons in the streets. Methinks I hear someone enquiring, “What are all these people waiting for?” “Do you not know? He is to be buried to-day.” “And who is that?” “It is Spurgeon.” “What! the man that preached at the Tabernacle?” “Yes; he is to be buried to-day.” That will happen very soon; and when you see my coffin carried to the silent grave, I should like every one of you, whether converted or not, to be constrained to say, “He did earnestly urge us, in plain and simple language, not to put off the consideration of eternal things. He did entreat us to look to Christ.”1

“Look unto Me, and be ye saved, all the ends of the earth”: back in January 1850, those had been the words that had first shown Spurgeon the way of salvation.

I had been waiting to do fifty things, but when I heard that word, “Look!” what a charming word it seemed to me! Oh! I looked until I could almost have looked my eyes away. There and then the cloud was gone, the darkness had rolled away, and that moment I saw the sun; and I could have risen that instant, and sung with the most enthusiastic of them, of the precious blood of Christ, and the simple faith which looks alone to Him.2

For forty-two years, then, from his conversion to his death, looking to Christ crucified for life remained the touchstone of Spurgeon’s own life and ministry. Having found new life in Christ himself, he dedicated his days to entreating all others: “look to Christ.”

A Christ-Centered Theology

This is a book about Spurgeon’s theology of the Christian life, and those were the concerns that lay at the heart of it. Spurgeon was unreservedly Christ-centered and Christ-shaped in his theology; and he was equally insistent on the vital necessity of the new birth. The Christian life is a new life in Christ, given by the Spirit and won by the blood of Jesus shed on the cross. Spurgeon’s was, therefore, a cross-centered and cross-shaped theology, for the cross was “the hour” of Christ’s glorification (John 12:23–24), the place where Christ was and is exalted, the only message able to overturn the hearts of men and women otherwise enslaved to sin. Along with Isaiah 45:22, one of Spurgeon’s favorite Bible verses was John 12:32: “And I, when I am lifted up from the earth, will draw all people to myself.”

Sometimes Spurgeon spoke of the glory of God as his “chief” or “great” aim, but that did not in any way temper his Christ-focus or his insistence on the importance of the new birth. “The glory of God being our chief object we aim at it by seeking the edification of saints and the salvation of sinners,” he explained.3 “Our great object of glorifying God is . . . to be mainly achieved by the winning of souls.”4 In other words, as he saw it, the glory of God is displayed and seen most clearly in God’s self-giving through Christ. God glorifies himself in graciously giving sinners his own abundant life in Christ through the Spirit.

What I have attempted here is to let Spurgeon’s theology of the Christian life shape the very structure—as well as the content—of this book. This is not a comprehensive analysis of Spurgeon’s overall theology, nor is it a biography, though it should help readers get to know both the man and the broad brushstrokes of his theology. We will start with a look at the man himself, to see how he lived out and embodied his own theology. Nothing so grand as an attempt at a mini-biography—this is more a personal introduction. For in the man himself, so fizzing with life, we see not just a unique personality but an example and personification of the life to be found and enjoyed in Christ. Spurgeon concretely lived out his belief that the Christian life is not a dull, ethereal existence on some higher, invisible plane. It is being more full, more human—brighter, more involved and more lively. So he would encourage his students:

Labour to be alive in all your duties. . . . Brethren, we must have life more abundantly, each one of us, and it must flow out into all the duties of our office: warm spiritual life must be manifest in the prayer, in the singing, in the preaching, and even in the shake of the hand and the good word after service. . . .

Be full of life at all times, and let that life be seen in your ordinary conversation.5

Then, after a look at the man himself, we will consider the relentless Christ-centeredness of his theology and preaching. After that, we will move to his emphasis upon (and understanding of) the new birth before at last turning to how he saw the Christian life. And at the very center of it all will be a chapter dedicated to his theology of the cross, that blood-soaked throne of Christ and the means of giving us life.

There is something else I have wanted this book to do: to let Spurgeon speak and minister to readers directly. In my own experience, I generally find reading Spurgeon himself like breathing in great lungfuls of mountain air: he is bracing, refreshing, and rousing. I want, therefore, to try to make myself scarce and let Spurgeon leap at readers himself.

And I have a hope for this book: that through it Spurgeon’s sermons and writings might be more widely read. Spurgeon is, understandably and quite rightly, a Baptist hero. Yet, a hundred and twenty-five years after his death, his real influence still remains largely confined to Baptist circles. Elsewhere he tends to be treated as little more than a fund of delicious but disconnected proverbs. This, it seems to me, should not be. While I share most of Spurgeon’s theology and many of his interests, and was raised just a short walk from Spurgeon’s childhood home, I am an Anglican. Spurgeon said of men like me, “I cannot tell . . . how it is these Church of England men are so attached to me. I have said some very severe things about their Church, and yet I have many devoted friends among them.”6 Yes, many of us non-Baptists are his friends. But not many enough. And just as Luther should not be cooped up only among Lutherans, nor Owen among Congregationalists, so Spurgeon should be enjoyed by all. He offers a robustly biblical and thoroughly rounded theology of the Christian life that deserves to be read by all—and all the more for the sheer zing with which he says it.

Spurgeon the Theologian?

And yet, was Spurgeon really a theologian? No doubt at all he was a great and influential preacher. In person he preached up to thirteen times per week, gathered the largest church of his day, and could make himself heard in a crowd of twenty-three thousand people (without amplification). In print he published some eighteen million words, selling over fifty-six million copies of his sermons in nearly forty languages in his own lifetime. But none of that is quite the same as to say that he was a theologian. Indeed, some antagonists insisted quite categorically that he was not. According to the Dean of Ripon, who crossed swords with Spurgeon over the question of baptism, Spurgeon “is to be pitied, because his entire want of acquaintance with theological literature leaves him utterly unfit for the determination of such a question, which is a question, not of mere doctrine, but of what may be called historical theology.”7

With such things having been said about Spurgeon, many were quietly surprised in 1964 when the eminent Lutheran theologian Helmut Thielicke wrote his Encounter with Spurgeon, a work in which he commended Spurgeon in the very warmest terms. Really, they wondered, was a self-educated Victorian preacher worthy of the attention of the rector of Hamburg University? It was the beginning of a change that Spurgeon seems to have foreseen: “For my part,” he had written, “I am quite willing to be eaten of dogs for the next fifty years; but the more distant future shall vindicate me.”8

As much as anything, what has thrown people here is the sheer lucidity of his style. He wrote and spoke with such limpid prose, it could all too easily be mistaken for shallow simplicity. But, Spurgeon knew, to think that difficulty of style is a true indicator of depth of substance is only the mistake of the intellectually proud.

Brethren, we should cultivate a clear style. When a man does not make me understand what he means, it is because he does not himself know what he means. . . . If you look down into a well, if it be empty, it will appear to be very deep; but if there be water in it, you will see its brightness. I believe that many “deep” preachers are simply so because they are like dry wells with nothing whatever in them, except decaying leaves, a few stones, and perhaps a dead cat or two. If there be living water in your preaching, it may be very deep, but the light of the truth will give clearness to it.9

Indeed, he believed, such clarity of expression is part of the Christlike humility to which all theologians and ministers of the Word are called.

Some would impress us by their depth of thought, when it is merely a love of big words. To hide plain things in dark sentences, is sport rather than service for God. If you love men better, you will love phrases less. How used your mother to talk to you when you were a child? There! do not tell me. Don’t print it. It would never do for the public ear. The things that she used to say to you were childish, and earlier still, babyish. Why did she thus speak, for she was a very sensible woman? Because she loved you. There is a sort of tutoyage, as the French call it, in which love delights.10

Almost as damning for his reputation as a theologian was his refusal to dabble in speculation or spend time on peripheral matters. “Speculation,” he declared, “is an index of the spiritual poverty of the man who surrenders himself to it.”11 Now certainly he was a man of broad interests, but he lived with such a sense of urgency and such a conviction of the sufficiency of Christ that the need to preach Christ crucified tended to trump worrying over obscure Scriptures or off-center doctrines.

There is, certainly, enough in the gospel for any one man, enough to fill any one life, to absorb all our thought, emotion, desire, and energy, yea, infinitely more than the most experienced Christian and the most intelligent teacher will ever be able to bring forth. If our Master kept to his one topic, we may wisely do the same, and if any say that we are narrow, let us delight in that blessed narrowness which brings men into the narrow way. If any denounce us as cramped in our ideas, and shut up to one set of truths, let us rejoice to be shut up with Christ, and count it the truest enlargement of our minds.12

He is so glorious, that only the infinite God has full knowledge of Him, therefore there will be no limit to our study, or narrowness in our line of thought, if we make our Lord the great object of all our thoughts and researches.13

Yet, for all that, Spurgeon was, quite self-consciously, a theologian. Avid in his biblical, theological, and linguistic study, he believed that every preacher should be a theologian, because it is only robust and meaty theology that has the nutritional value to feed and grow robust Christians and robust churches.14

Some preachers seem to be afraid lest their sermons should be too rich in doctrine, and so injure the spiritual digestions of their hearers. The fear is superfluous. . . . This is not a theological age, and therefore it rails at sound doctrinal teaching, on the principle that ignorance despises wisdom. The glorious giants of the Puritan age fed on something better than the whipped creams and pastries which are now so much in vogue.15

Thus, while he was no theological innovator, he sought to avoid superficiality in theology with just the same enthusiasm as he avoided obscurity in communication.

The notion that we have only to cry, “Believe in the Lord Jesus Christ, and thou shalt be saved,” and repeat for ever the same simplicities, will be fatal to a continuous ministry over one people if we attempt to carry it out. The evangelical party in the Church of England was once supreme; but it lost very much power through the weakness of its thought, and its evident belief that pious platitudes could hold the ear of England.16

That combination of concerns, for theological depth with plainness of speech, made Spurgeon a preeminent pastorally minded theologian. He wanted to be both faithful to God and understood by people. That, surely, is a healthy and Christlike perspective for any theologian. And that is why he is such a rewarding and refreshing thinker.

1Autobiog., 4:375.

2Autobiog., 1:106.

3Lectures, 2:264.

4Lectures, 2:265.

5ARM, 188–91. Hereafter, all emphasis in quotations is original unless otherwise indicated.

6 William Williams, Personal Reminiscences of Charles Haddon Spurgeon (London: Passmore & Alabaster, 1895), 70–71.

7 H. L. Wayland, Charles H. Spurgeon: His Faith and Works (Philadelphia: American Baptist Publication Society, 1982), 212.

8ARM, 360.

9ARM, 42.

10ARM, 353.

11ARM, 140.

12S&T: 1877, 177.

13ARM, 53.

14ARM, 35. Spurgeon’s study of the Greek and Hebrew Scriptures is apparent throughout his sermons (for Greek, see NPSP, 3:257, 454; 5:287; MTP, 8:399; 11:184; 20:209, 237, 441, 500; 24:219; 25:115, 309, 350; 30:58, 514; 32:1, 145–75; 33:184; 36:95, 206, 407; 41:182; 53:324; 56:11, 405; 58:26; for Hebrew, see NPSP, 1:224; 2:93; MTP, 20:199, 260–61; 21:709; 23:31, 74, 266, 303, 511, 689; 28:400; 32:160, 350, 705; 34:10, 78, 107, 234; 38:407, 470; 56:366). He also referred to a number of Latin works in his sermons, lectures, and commentaries, making it clear, for instance, that he liked to read Augustine in Latin (MTP, 25:134; 28:415; 35:190; 37:87). “The acquisition of another language affords a fine drilling for the practice of extempore speech,” he wrote.

Brought into connection with the roots of words, and the rules of speech, and being compelled to note the differentia of the two languages, a man grows by degrees to be much at home with parts of speech, moods, tenses, and inflections; like a workman he becomes familiar with his tools, and handles them as every day companions. I know of no better exercise than to translate with as much rapidity as possible a portion of Virgil or Tacitus, and then with deliberation to amend one’s mistakes. (Lectures, 1:160)

15S&T: 1883, 125–26.

16S&T: 1881, 39.

PART 1

CHARLES SPURGEON

CHAPTER 1

A MAN FULL OF LIFE

In person Mr. Spurgeon was of medium height and stout build. He had a massive head and large features of the heavy English type. In repose his face, while strong, might have been called phlegmatic if not dull in expression. But when he spoke it glowed with animation of thought, quick flashes of humour, benignity, and earnestness and every phase of the emotion that stirred within him. He had many elements of power as a preacher. His voice was of marvellous sonority and sweetness. His language with all its simplicity, was marked by faultless correctness and inexhaustible wealth of diction. He was as far as possible from being a rough or course speaker although he had at ready command a vast vocabulary of homely Saxon words. No one from merely reading his sermons, can form any idea of their effect when delivered. . . . In listening to Mr Spurgeon, one recognised that the chief element of his commanding force in the pulpit was his profound and burning conviction. The message he gave had for him supreme importance. All his soul went with its utterance. The fire of his zeal was consuming, intense, resistless.1

Before we wade into Spurgeon’s theology of the Christian life, we must get to know the man himself a little. To do that, I want to get behind the public figure to see something of the man’s own personality and character. For there is a unanimous and oft-repeated theme found in the witness of those who had personal dealings with him: Spurgeon was a man who went at all of life full-on. He was not simply a large presence in the pulpit. In life, he laughed and cried much; he read avidly and felt deeply; he was a zealously industrious worker and a sociable lover of play and beauty. He was, in other words, a man who embodied the truth that to be in Christ means to be made ever more roundly human, more fully alive. In fact, we need to be clear that his liveliness of character, while expressed in ways particular to him, was not a mere matter of unique or inherited personality: it was a natural but wholly self-conscious expression of his theology. As he put it,

We ought each one to be like that reformer who is described as “Vividus vultus, vividi occuli, vividæ manus, denique omnia vivida,” which I would rather freely render—“a countenance beaming with life, eyes and hands full of life, in fine, a vivid preacher, altogether alive.”2

We ought to be all alive, and always alive. A pillar of light and fire should be the preacher’s fit emblem.3

Mr. Great-Heart

It takes no great insight to see that Spurgeon was a big-hearted man of deep affections. His printed sermons and lectures still throb with passion. At times the emotional freight of his sermon would even overcome him, especially when it was about the crucifixion of Christ. Once, when trying to recount how Christ was then “bruised, trodden, crushed, destroyed . . . sorrowful, even unto death” he had to break off, saying, “I must pause, I cannot describe it. I can weep over it, and you can too.”4 It was no mere pulpiteer’s tactic, though: his private and personal letters to family and friends reveal exactly the same intensity of emotion, and about just the same sorts of issues he would address in public.

Perhaps the best insight into Spurgeon’s character comes through the introduction he once gave to his equally large-framed friend, John Bost. Calling Bost “a man after our own heart,” he gave what amounts to a remarkably revealing self-description:

John Bost is great as well as large. . . . Here is a man after our own heart, with a lot of human nature in him, a large-hearted, tempest-tossed mortal, who has done business on the great waters, and would long ago have been wrecked had it not been for his simple reliance upon God. His is a soul like that of Martin Luther, full of emotion and of mental changes; borne aloft to heaven at one time and anon sinking in the deeps. Worn down with labour, he needs rest, but will not take it, perhaps cannot. . . . [I have] found him full of zeal and devotion, and brimming over with godly experience, and at the same time abounding in mirth, racy remark, and mother wit.5

This description is revealing in its honest acknowledgment of Bost’s (and his own) depression and struggle. For him, to be “large-hearted,” with “a lot of human nature” in this fallen world does not mean being a triumphalist, cheerily blustering past all difficulty. Spurgeon could never have done that, as we shall see in chapter 11. Experiencing life in Christ, the Man of Sorrows, must entail suffering. Yet life in Christ must also involve real cheer, “abounding in mirth, racy remark, and mother wit.”

There were dangers for one so tenderhearted. Spurgeon publicly admitted that his temperamental sensitivity inclined him to be fearful.6 Combine this with his marked generosity in dealing with people, and he could—and did—sometimes fail in his discernment of character, becoming victim to those who would abuse his financial openhandedness. Yet tenderheartedness should not be confused with weakness: along with expressing his love for Christ and people, Spurgeon could demonstrate a real hatred for wickedness and injustice. Again and again, he spoke of how he would boil with anger at pastoral abuse, church politicking, and false teaching (especially any form of Roman Catholicism). And while he surely struggled, it would be wildly misguided to think of Spurgeon as a fragile pushover. It would be far better to say that tenderness saved him: it kept his robustness of character from steamrolling those weaker than himself, and channeled it for their benefit. His blend of vigor and tenderness made him fascinatingly feisty in showing compassion, as witnessed by this humor-filled letter of complaint to his publisher:

Dear Mr. Passmore,

When that good little lad came here on Monday with the sermon, late at night, it was needful. But please blow somebody up for sending the poor little creature here, late to-night, in all this snow, with a parcel much heavier than he ought to carry. He could not get home till eleven, I fear; and I feel like a cruel brute in being the innocent cause of having a poor lad out at such an hour on such a night. There was no need at all for it. Do kick somebody for me, so that it may not happen again.

Yours ever heartily,

C. H. SPURGEON.7

There, both in his care for a socially insignificant minor and in the playfulness of his rebuke, is revealed the man’s genial and benevolent large-heartedness. It was an aspect of Christlikeness he wanted to see in all believers, and one he believed essential for pastors: “Great hearts are the main qualifications for great preachers.”8 It was something he would speak about at length with his students, and it is worth hearing him at some length (for both his substance and his style!):

It is not every preacher we would care to talk with; but there are some whom one would give a fortune to converse with for an hour. I love a minister whose face invites me to make him my friend—a man upon whose doorstep you read, “Salve,” “Welcome;” and feel that there is no need of that Pompeian warning, “Cave Canem,” “Beware of the dog.” Give me the man around whom the children come, like flies around a honey-pot: they are first-class judges of a good man. . . . A man who is to do much with men must love them, and feel at home with them. An individual who has no geniality about him had better be an undertaker, and bury the dead, for he will never succeed in influencing the living. I have met somewhere with the observation that to be a popular preacher one must have bowels.9 I fear that the observation was meant as a mild criticism upon the bulk to which certain brethren have attained: but there is truth in it. A man must have a great heart if he would have a great congregation. His heart should be as capacious as those noble harbors along our coast, which contain sea-room for a fleet. When a man has a large, loving heart, men go to him as ships to a haven, and feel at peace when they have anchored under the lee of his friendship. Such a man is hearty in private as well as in public; his blood is not cold and fishy, but he is warm as your own fireside. No pride and selfishness chill you when you approach him; he has his doors all open to receive you, and you are at home with him at once. Such men I would persuade you to be, every one of you.10

A Life of Joy

Spurgeon was an unmistakably and deliberately earnest man. With a deep concern for the glory of Christ and the fate of the lost, he believed that Christians should be able to say with our master, “Zeal for your house will consume me” (John 2:17; cf. Ps. 69:9). Yet earnestness and zeal, for Spurgeon, were never to be confused with gloominess and melancholy. It is telling and entirely appropriate that a whole chapter of his “autobiography” (really a biography compiled from his diary, letters, and records) is titled “Pure Fun.” For, we are told, “it was felt that the record of his happy life would not be complete unless at least one chapter was filled with specimens of that pure fun which was as characteristic of him as was his ‘precious faith.’”11 It is another reason why he was and has remained so magnetic: Charles Spurgeon was fun.

Entirely upsetting the stereotype that the Victorian era was a long, charmless span of dusty prissiness, Spurgeon’s writings ripple with mirth. And evidently even they do not do justice to what he was like in person.12 The editor of his Lectures to My Students would thus be driven to insert attempts at explaining his various impressions and “voices,” as he impersonated pompous theologians and fools.13 Usually, though, one can still sense the humor that cannot quite be caught on a page:

I would say with regard to your throats—take care of them. Take care always to clear them well when you are about to speak, but do not be constantly clearing them while you are preaching. A very esteemed brother of my acquaintance always talks in this way—“My dear friends—hem—hem—this is a most—hem—important subject which I have now—hem—hem—to bring before you, and—hem—hem—I have to call upon you to give me—hem—hem—your most serious—hem—attention.”14

“What a bubbling fountain of humour Mr. Spurgeon had!” wrote his friend William Williams. “I have laughed more, I verily believe, when in his company than during all the rest of my life besides.”15 Few, it seems, expected to laugh so much in the presence of the zealous pastor; but Spurgeon knew this and seemed to take an impish delight in springing comedy on those around him. Grandiosity, religiosity, and humbug could all expect to be pricked on his wit. Sometimes rather more was broken. Spurgeon enjoyed telling the story of how, as a young pastor in Park Street, he had complained to his deacons about how stuffy and stifling it could get in the building, suggesting that they remove the upper panes of glass from some of the windows to let in more air. Nothing was done about it; but then one day it was found that someone had smashed those window panes out. Spurgeon offered a reward of five pounds for the discovery of the offender, who would then be given the money in thanks. This money the pastor then pocketed, being himself the culprit.16

But perhaps it is Spurgeon’s cigar smoking that best reveals his sunny playfulness as well as his vivacious willingness to enjoy created things. Personally, Spurgeon found great pleasure in cigars; he argued that the Bible gave him liberty to smoke them, and he believed they helped his throat as a preacher. He was sensitively aware, however, that many Christians felt otherwise, and he was keen not to offend or let them stumble over the issue. When his statement that he smoked “to the glory of God” was printed in the newspapers as if it had been a flippant crack, he was sorry that prominence had been given to what seemed to him a small matter, and quickly wrote to explain:

The expression “smoking to the glory of God” standing alone has an ill sound, and I do not justify it; but in the sense in which I employed it I still stand to it. No Christian should do anything in which he cannot glorify God; and this may be done, according to Scripture, in eating and drinking and the common actions of life. When I have found intense pain relieved, a weary brain soothed, and calm, refreshing sleep obtained by a cigar, I have felt grateful to God, and have blessed His name; this is what I meant, and by no means did I use sacred words triflingly.17

That said, in the right context he would happily use his cigar to replace religiosity with cheerful enjoyment of Christian liberty. William Williams records a day out he took with his students:

It was a beautiful early morning, and on arriving all were in high spirits—pipes and cigars alight, and looking forward to a day of unrestrained enjoyment. He was ready waiting at the gate, jumped up to the box-seat reserved for him, and, looking round with astonishment, exclaimed: “What, gentlemen! are you not ashamed to be smoking so early?” Here was a damper! Dismay was on every face. Pipes and cigars one by one failed and dropped out of sight. When all had disappeared, out came his cigar-case; he lit up and smoked away serenely. Astonishment was now on every face. One of the party nearest to him said, “I thought you said you objected to smoking, Mr. Spurgeon?” “Oh no,” he replied; “I did not say I objected. I asked if they were not ashamed, and it appears they were, for they have put them all out.” And he puffed away quite serenely.18

Humor flowed from Spurgeon naturally and freely, but he was acutely conscious of both the power and the danger of it. He held that in the pulpit it is “less a crime to cause a momentary laughter than a half-hour’s profound slumber,”19 yet his sermons were very far from being a stream of humor. This could sometimes be a challenge for him, as he once confessed to a listener who objected to some pulpit witticism of his: “If you had known how many others I kept back, you would not have found fault with that one, but you would have commended me for the restraint I had exercised.”20 “Were I not watchful, I should become too hilarious.”21 Yet, he explained, “God’s servants have no right to become mere entertainers of the public pouring out a number of stale jokes and idle tales without a practical point. . . . To make religious teaching interesting is one thing, but to make silly mirth, without aim or purpose is quite another.”22

For all that, it would be wholly inadequate and superficial simply to think of Spurgeon as chucklesome. Humor, he believed, is normally the fruit of something deeper. Sometimes it can come from no more than high spirits—and this, he admitted, was a temperamental challenge for him.

We must—some of us especially must—conquer our tendency to levity. A great distinction exists between holy cheerfulness, which is a virtue, and that general levity, which is a vice. There is a levity which has not enough heart to laugh, but trifles with everything; it is flippant, hollow, unreal.23

At other times humor can be the defense mechanism of the sad, a light thrown out into the darkness. Sometimes it is the cruel weapon of the proud or insecure, brandished as a sneer or a sarcastic put-down.24 Sometimes it is the bright weapon of righteousness, lancing both gloom and sin.