15,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

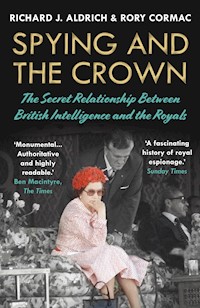

A Daily Mail Book of the Year and a The Times and Sunday Times Best Book of 2021 'Monumental.. Authoritative and highly readable.' Ben Macintyre, The Times 'A fascinating history of royal espionage.' Sunday Times 'Excellent... Compelling' Guardian For the first time, Spying and the Crown uncovers the remarkable relationship between the Royal Family and the intelligence community, from the reign of Queen Victoria to the death of Princess Diana. In an enthralling narrative, Richard J. Aldrich and Rory Cormac show how the British secret services grew out of persistent attempts to assassinate Victoria and then operated on a private and informal basis, drawing on close personal relationships between senior spies, the aristocracy, and the monarchy. This reached its zenith after the murder of the Romanovs and the Russian revolution when, fearing a similar revolt in Britain, King George V considered using private networks to provide intelligence on the loyalty of the armed forces - and of the broader population. In 1936, the dramatic abdication of Edward VIII formed a turning point in this relationship. What originally started as family feuding over a romantic liaison with the American divorcee Wallis Simpson, escalated into a national security crisis. Fearing the couple's Nazi sympathies as well as domestic instability, British spies turned their attention to the King. During the Second World War, his successor, King George VI gradually restored trust between the secret world and House of Windsor. Thereafter, Queen Elizabeth II regularly enacted her constitutional right to advise and warn, raising her eyebrow knowingly at prime ministers and spymasters alike. Based on original research and new evidence, Spying and the Crown presents the British monarchy in an entirely new light and reveals how far their majesties still call the shots in a hidden world. Previously published as The Secret Royals.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

SPYING AND THE CROWN

Richard J. Aldrich is a Professor of International Security at the University of Warwick. A regular commentator on war and espionage, he has written for The Times, Guardian and Daily Telegraph. He is a prize-winning author of several books, including The Hidden Hand and GCHQ.

Rory Cormac is a Professor of International Relations at the University of Nottingham, specializing in secret intelligence and covert action. He is the author of Disrupt and Deny and How To Stage A Coup, and co-author, with Richard J. Aldrich, of The Black Door.

‘This monumental book is really a history of the British secret services, focusing on the fascinating moments when this intersects with royal history... Authoritative and highly readable… As every page of this book attests, the royals have always been involved in secretly directing the affairs not just of this country but of many others.’ Ben Macintyre, The Times, ‘Book of the Week’

‘Bizarre and disturbing episodes are revealed in this excellent history of the royal family’s relationship with espionage... Through unbelievably thorough research – all of it fully referenced for grateful future scholars – they have compiled something comprehensive and compelling.’ Guardian

‘A fascinating history of royal espionage… The book, which stretches back to Elizabeth I and her spymaster Sir Francis Walsingham, has something of interest on pretty much every page.’ Rowland White, Sunday Times

‘Their mastery of a subject that is extensive both chronologically and in its geographical scope is assured and impressive… An intriguing alternative narrative of British royal history.’ Matthew Dennison, Sunday Telegraph

‘Aldrich and Cormac have written an important book. Packed with new material and fresh insights, it offers an original way of looking at royal history. It’s also a very good read.’ Jane Ridley, Literary Review

‘[A] thorough and informed survey of how matters of high state have really worked – and work.’ Alan Judd, Spectator

Also by Richard J. Aldrich & Rory Cormac

The Black Door: Spies, Secret Intelligence and British Prime Ministers

Spying on the World: The Declassified Documents of the Joint Intelligence Committee, 1936–2013 (with Michael S. Goodman)

Also by Richard J. Aldrich

GCHQ: The Fully Updated Centenary Edition

The Hidden Hand: Britain, America and Cold War Secret Intelligence

Intelligence and the War Against Japan: Britain, America and the Politics of Secret Service

Also by Rory Cormac

How To Stage A Coup: And Ten Other Lessons from the World of Secret Statecraft

Disrupt and Deny: Spies, Special Forces and the Secret

Pursuit of British Foreign Policy

Confronting the Colonies: British Intelligence and Counterinsurgency

First published in Great Britain in 2021 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Th is paperback edition fi rst published in Great Britain in 2022 by Atlantic Books.

Previously published as Th e Secret Royals: Spying and the Crown, from Victoria to Diana

Copyright © Richard J. Aldrich and Rory Cormac, 2021

The moral right of Richard J. Aldrich and Rory Cormac to be identified as the authors of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Paperback ISBN: 978-1-78649-914-1

E-book ISBN: 978-1-78649- 913-4

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic Books

An Imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

To Libby and Joanne – who are just the best!

CONTENTS

List of Illustrations

Introduction: 007

1. Elizabeth I and Modern Espionage

2. Popish Plots and Public Paranoia

Part I: The Rise and Fall of Royal Intelligence

3. Queen Victoria: Assassins and Revolutionaries

4. Queen Victoria’s Secrets: War and the Rise of Germany

5. Queen Victoria’s Great Game: Empire and Intrigue

6. Queen Victoria’s Security: Fenians and Anarchists

7. Edward VII and the Modernization of Intelligence

Part II: Royal Relations and Intrigues

8. King George V and the Great War

9. King George V and the Bolsheviks

10. Abdication: Spying on Edward VIII and Wallis Simpson

Part III: Royals and Spies at War

11. Outbreak of the Second World War

12. War in the Americas

13. The End of the Second World War

14. Raiding Missions: Fighting for the Secret Files

Part IV: Royal Secrets

15. Princess Elizabeth: Codename 2519

16. Queen Elizabeth II: Coronation and Cold War

17. Nuclear Secrets

Part V: Royal Diplomacy

18. Queen Elizabeth’s Empire: Intrigue and the Middle East

19. Discreet Diplomacy: The Royals in Africa

20. Discreet Diplomacy: The Global Queen

Part VI: Protecting the Realm and the Royals

21. Terrorists and Lunatics, 1969–1977

22. Terrorists and Lunatics, 1979–1984

23. Going Public

24. Bugs and Bugging

25. The Diana Conspiracy

Conclusion: The Secret Royals

Ruling the Past: A Note on Methods

Acknowledgements

Endnotes

Bibliography

Index

ILLUSTRATIONS

First section

Elizabeth I’s ‘Rainbow Portrait’ (Wikimedia Commons)

Queen Victoria with her eldest daughter Vicky (Private collection)

George V and Tsar Nicholas II with their heirs (Private collection)

Rasputin (Universal History Archive/Getty Images)

Fridtjof Nansen (Frum Museum)

The police arrest the would-be assassin George McMahon (Ernest Brooks/Getty Images)

Edward, Wallis with Charles and Fern Bedaux (US National Archives and Records Administration)

The Windsors loose in Florida, 1941 (US National Archives and Records Administration)

Gray Phillips followed Edward with care in the 1940s (Private collection)

‘Mouse’ Fielden (Private collection)

The royal family inspect the 6th Airborne Division (© IWM H 38612)

George VI inspects a special forces raiding jeep (© IWM H 19947)

George VI inspects a landing craft (Military Images/Alamy Stock Photo)

Second section

George VI in Monty’s caravan (© IWM TR 2393)

George VI and Princess Margaret (Private collection)

The Treetops Hotel in Kenya (Private collection)

Queen Elizabeth II and Marshall Tito (AFP via Getty Images)

John F. Kennedy, Mountbatten and Lyman Lemnizter (JFK Library)

Queen Elizabeth II with President Kwame Nkrumah in Ghana (Kara University Library)

Queen Elizabeth II and Anthony Blunt (PA Images/Alamy Stock Photo)

Ian Fleming with Sean Connery (PictureLux/The Hollywood Archive/Alamy Stock Photo)

Prince Charles at Cambridge University (© Hulton-Deutsch Collection/Corbis via Getty Images)

Prince Charles enjoys pistol practice in West Berlin (INGA SA)

Aftermath of the attempted kidnap of Princess Anne (PA/Alamy Stock Photo)

Queen Elizabeth II with Harold Wilson (Ford Library)

Queen Elizabeth II with the Shah of Iran (PA/Alamy Stock Photo)

Prince Charles eyes Idi Amin (Keystone/Getty Images)

Diana, Princess of Wales (Tim Ockenden/Alamy Stock Photo)

Queen Elizabeth II unveils a plaque to mark the centenary of GCHQ (Niklas Halle’n/AFP via Getty Images)

INTRODUCTION: 007

On Her Majesty’s Secret Service.

Ian Fleming1

ON A BALMY summer evening in late July 2012 the world’s most famous intelligence officer arrived at Buckingham Palace in an iconic black cab. Dressed in his trademark tuxedo, he skipped up the central red staircase and, flanked by the royal corgis, entered a gilded room. At a desk in the corner sat Queen Elizabeth II. She kept him waiting; he glanced at the clock and coughed politely.

‘Good evening, Mr Bond,’ she said, turning to face him. ‘Good evening, your majesty,’ he quietly responded.

James Bond followed her as she made her way down the stairs and headed towards a helicopter waiting on the lawn outside. Moments later, Agent 007 and the queen jumped from the helicopter in a dramatic parachute drop down towards the Olympic stadium in east London. The crowd gasped as they vanished from sight, before Elizabeth reappeared, wearing the same pink dress, in the royal box. The sequence formed the highlight of the Olympic Games opening ceremony.

Organized by the Oscar-winning director Danny Boyle and partly filmed in Buckingham Palace, this masterpiece of deception involved the real queen, stunt doubles and cameo roles for three royal corgis, Monty, Holly and Willow. In over fifty years of Bond feature films, the paths of 007 and the royal family have frequently crossed. Prince Charles visited the Bond set at Pinewood Studios to the west of London in 2019. Photographs showed him inspecting the set and chatting to James Bond himself. More discreetly, producers borrowed some of the most striking interior designs featured in the iconic film Goldfinger from Princess Margaret’s palace. The early 007 films were known for their conspicuous consumption, high fashion, exotic air travel and the latest designs. Margaret’s abode fitted right in.

Few realize that these momentary connections are far from fantasy and instead capture a fleeting glance of Britain’s most secret partnership – the British monarchy and their secret services.

Surprisingly, the queen, like her predecessors, is no stranger to the real secret service. Even before her coronation, the young Princess Elizabeth had met two Albanian agents near a hidden MI6 training camp on Malta. Sporting Thompson submachine guns and training on secret transmitters, they were preparing to overthrow the communist government in Tirana. Shortly after ascending the throne in 1952, the queen was discussing a troublesome Middle Eastern leader with officials. She quipped about assassinating him.

The queen knows more state secrets than any living person – and, unlike her prime ministers, she keeps them. The queen is a human library of intelligence history. She knew about the British nuclear weapons programme at a remarkably early stage. And she knew more about the Soviet mole, Anthony Blunt, still in her employment as Surveyor of the Queen’s Pictures, than even the prime minister did. Later, she invited the CIA’s head of operations to Buckingham Palace to ask him how ‘my boys’ were treating him. The senior CIA officer was surprised that Elizabeth knew about his real job at all.

The queen has spent time in the SAS ‘Killing House’ in Hereford where special forces hone their deadly skills. She stood unflinching for the most part as operators trained with live ammunition for hostage rescue operations. Throughout her long reign, Elizabeth has met many heads of Britain’s intelligence agencies. When Stella Rimington, the first publicly named leader of MI5, attended lunch at Buckingham Palace, the royal household helped her to escape via an inconspicuous exit in order to avoid the assembled reporters desperate to know what a monarch might say to a spy chief.

The royal family and the secret services have much in common. They are two of Britain’s most important institutions. They are small and secretive, seen by many as ‘the establishment’. They feature prominently in the popular imagination. They are heavily mythologized and often misunderstood.

THE SECRET ROYALS uncovers the remarkable relationship between the royal family and the intelligence community since the reign of Queen Victoria. It argues that modern intelligence grew out of persistent attempts to assassinate Victoria and then operated on a private and informal basis, drawing on close personal relationships between senior spies, the aristocracy and the monarchy. Moreover, it is a remarkable place where women rulers, rather more than men, are often playing the role of a royal ‘M’, standing at the centre of what has hitherto been assumed to be a masculine world.

Britain’s spies are ‘crown servants’ and, since the accession of Victoria in 1837, they have served mostly women at the top. Early in her career, Margaret Thatcher reflected on the symbolic importance of the young Queen Elizabeth, noting that it would ‘help to remove the last shreds of prejudice against women aspiring to the highest places’. Victoria does not seem to have shared her views, famously observing that ‘Feminists ought to get a good whipping.’

The mid-Victorian era was a period of political upheaval: royal intelligence channels clashed with amateur equivalents used by nation states; royals with multiple nationalities faced increasing suspicion from politicians; and monarchs used private sources to bypass their own Cabinets and protect their dynastic interests. Victoria was often at odds with her own government, for example over issues of surveillance, and used private royal intelligence sources to support – but also outmanoeuvre – government policy. She acted as intelligence gatherer, analyst and, in modern jargon, ‘consumer’. Her son, King Edward VII, had restricted access to intelligence when prince, largely because of fears of blackmail and poor security practices. Despite this, he tried to continue in a similar mould to Victoria when king, drawing on private family networks across the Continent.

In 1909, the first chief of MI6, Mansfield Cumming, proclaimed himself a servant of the king, not the prime minister. His successors’ royal connections often allowed them to move more easily in the royal court than in the corridors of Whitehall. This reached its apotheosis before the Russian Revolution when MI6 intervened to try to save the Russian tsar, the king’s cousin, from disaster. Afterwards, fearing a similar revolt in Britain, private networks provided King George V with intelligence on the loyalty of his own subjects.

In 1936, the dramatic abdication of Edward VIII formed a dangerous turning point. What originally started as family feuding over a romantic liaison with the American divorcee Wallis Simpson, escalated into a national security crisis. Fearing the couple’s Nazi sympathies as well as domestic instability, British spies turned their attention towards Edward, creating profound dilemmas for intelligence officers who had previously been his drinking partners.

They worried about when and how to intervene. As fears grew, MI5 spied on the king himself, hiding in the bushes of Green Park near Buckingham Palace to access a telephone junction box and eavesdrop on his personal telephone calls. Even after the abdication, he remained a high priority target as spies reported back on his political views and on the less than salubrious company he kept, assessing him and his wife as ‘fifth columnists’. Reading these surveillance reports on his activities, the Foreign Office complained of his ‘fascist sympathies’. Sent away into a kind of Caribbean exile as governor of the Bahamas, the duke of Windsor was, bizarrely, both the recipient of secret service reports and under close surveillance by the same agencies.

During the Second World War, his brother and successor, King George VI, gradually restored trust between the secret world and the House of Windsor. Although initially tarnished as an enthusiastic appeaser, George eventually acquired inside knowledge of the electronic ‘Wizard War’ that would gradually turn the tide against the Axis. The king knew all the secrets in the land, from radar research to incredibly sensitive decrypted Enigma material produced at Bletchley Park, and from secret black radio stations to the legendary D-Day deception masterminded by MI5.

He became involved in several Special Operations Executive escapades, enjoyed a personal tour of their gadgets and gizmos, and decorated numerous secret agents. The king maintained a keen interest until his death, after which the last copy of an eye-wateringly secret report on deception operations was found locked in his private despatch box by the queen.

In the 1950s, the young Queen Elizabeth II continued her father’s fastidious interest in secret statecraft, from nuclear bunkers to weekly intelligence assessments. She was more than what the eminent constitutional historian Peter Hennessy called a ‘gilded sponge’, and, exercising her constitutional right to encourage, warn and be consulted, would raise an eyebrow knowingly at prime ministers and spymasters alike. On occasions, the Foreign Office would deploy her on subtle diplomacy. On other occasions, she made suggestions of her own, often about the fate of fellow monarchs.

This close relationship lasted through four decades of the Cold War. Then, in the early 1990s, Queen Elizabeth’s private secretary, Sir Robert Fellowes, lunched at MI6’s crumbling headquarters, Century House. This dilapidated tower block situated in a singularly unfashionable borough south of the river seemed to symbolize an uncertain future for the agency at the end of the Cold War. With the icy conflict clearly over, Elizabeth wanted to know if MI6 still had a purpose in this new world. What should he tell her? Gerry Warner, its second in command, replied: ‘Please tell her it is the last penumbra of her empire.’2

THE SECRET ROYALS argues that the relationship between spies and royals has evolved into something rather unusual. It has moved from the informal and personal to something more formal with a real role for senior royals. In the last century, Stewart Menzies, chief of MI6, himself a stepson of the king’s equerry, traded off rumours that he was an illegitimate son of another king. Now, the head of MI6 nominates its most brilliant officers for private awards from Prince Charles, who has long been fascinated by secret operations. In a dark world where life often hangs by a thread, these awards are the equivalent of a secret Victoria Cross – for acts of gallantry or ingenuity that we will never hear about. Intelligence agencies receive visits from Prince Charles in this role, signified by the flying of the royal ensign. Demonstrating the close relationship, Queen Elizabeth appointed a recent head of MI5, Andrew Parker, as lord chamberlain in 2021, a senior member of her royal household.

Monarchy has directly shaped intelligence. Attempts to assassinate Queen Victoria stimulated the creation and growth of Special Branch. Ever since, intelligence has maintained an important function of keeping the monarch alive. In return, intelligence has shaped monarchy. Discreet protection and early warning allowed kings and queens to remain accessible and visible in dangerous eras of war and terrorism.

Monarchy drove intelligence in other ways too. Access to intelligence enabled kings and queens to intervene in foreign and security policy. Royal marriages created important dynastic intelligence networks across the Continent providing sensitive information back to the palace. The high-level attendance at royal marriages and funerals made them a forerunner of the modern G-20 summit, with opportunities for diplomacy and espionage. It could even be argued that states’ frustration at private royal channels and the dynastic interests they pursued helped spur the creation of more official national intelligence services across Europe.

In return, intelligence shaped monarchy. Tensions over secret information sat at the heart of debates about the role of the constitutional monarch in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Moreover, the competition between royal intelligence and that of the nation state formed part of a broader clash between dynastic and state interests during a period of revolutionary upheaval. In this sense, the relationship between intelligence and monarchy played a part in shaping the nationalism of the nineteenth century.

Much of this took place against a backdrop of war and insecurity. European wars of the nineteenth century allowed Queen Victoria to flex her royal networks, but those further away in places like Russia and the imperial frontiers led to her demanding greater intelligence coverage. The end of the First World War decimated the royal intelligence system but, by this time, state intelligence was becoming more institutionalized. Across Europe, royals were not only decimated but also disrespected; in the 1919 election, when Lloyd George campaigned on the slogan ‘Hang the Kaiser’ he was openly urging the lynching of the king’s cousin. Even then, King George V maintained his own military intelligence network and found himself surrounded by those working for secret organizations. The Second World War salvaged and formalized the relationship between king and intelligence.

Secret intelligence moved seamlessly from dynastic and family politics to national security politics. Yet the monarch still maintains an important role. How kings and queens access and use intelligence directly affects their ability to exercise their constitutional rights – and ultimately their power. Famously, the Victorian essayist Walter Bagehot suggested that the crown’s ‘mystery is its life. We must not let in daylight upon magic.’ Nowhere is this mystery more pronounced than in the relationship between the monarchy and the intelligence services. It is now possible to let a little daylight into the most secret rooms of the British state.

1

ELIZABETH I AND MODERN ESPIONAGE

‘Do not tell secrets to those whose faith and silence you have not already tested.’

Queen Elizabeth I, 16001

AROUND 1600, THREE years before her death, a stunning painting of Queen Elizabeth I was commissioned. Known as the Rainbow Portrait, it still hangs in Hatfield House, the historic home of her advisers, the Cecils, on the northern edge of London. Her face is ageless and perfect. At the height of her powers, glorying in her defeat of the Spanish Armada a decade earlier, this image is rich with complex symbols and hidden meanings. Eyes and ears are embroidered all over Elizabeth’s orange dress, warning that she sees and hears everything. The dominant theme is surveillance; it is all about spies and royals.2

The painting is more than a visible celebration of the triumph of Elizabeth’s intelligence networks over many rebellions, plots and conspiracies. Her left arm sports the most cunning of all creatures, a vast jewelled snake. It symbolizes that intelligence is only powerful in the hands of those who understand its complexities, who know how to use it wisely, and who then have the courage to take timely action. In her right hand, she holds a rainbow, a symbol of peace: the ultimate prize of her statecraft. Elizabeth is perhaps saying that without her impressive spy network, without her skill in using intelligence and her capability in covert action, there could be no peace.3

In England, spies and royal statecraft were episodic and opportunistic partners.4 Elizabeth was the first monarch who can claim to have presided over an organized intelligence community, perhaps reaching its apogee during the penultimate decade of the sixteenth century when she battled the Spanish Armada. Here, familiar tradecraft suddenly becomes apparent, including human espionage, codebreaking and interrogation, but also more complex ‘dark arts’ of covert action, double agents and even strategic deception. At first glance, all this seems strikingly modern. Indeed, the historian Stephen Budiansky argues that Elizabeth and her spymasters constitute ‘the birth of modern espionage’.5

Yet in other ways, Elizabeth’s spymasters are peculiar and distant. They relied on private endeavour and personal connections more than formal machinery. Some of her most loyal subjects went into debt, even bankruptcy, subsidizing this strange assemblage of subterranean activities only partly funded by the crown. Intelligence was sometimes run alongside family members from their own private houses – a rather vernacular form of espionage.6

Elizabeth’s inner circle, including William Cecil, Francis Walsingham and the earl of Leicester, were all heavily involved in intelligence work. Espionage fascinated the queen, raising the question of how much she personally knew about these remarkable, and often competing, clandestine structures operating in her name. Was she an active intelligence manager, or else to what extent was she manoeuvred by competing courtiers who were spinning intelligence for their own ends? The Elizabethan spy network was impressive in its geographical and political range, but the hand of Elizabeth herself is often hard to trace.7

The Elizabethan age has been much celebrated and so has its supposedly modern spy system. But over the years we have been fed an anachronism: the idea of a proto-modern collective and constitutional secret service, working largely for national security with Elizabeth commanding her forces against the invading Spanish Armada – a curiously Churchillian vision. One can almost imagine her puffing a cigar and orating ‘we shall fight them on the beaches’.8

Some see the ballooning intelligence bureaucracy as a successful attempt to isolate Elizabeth from policymaking; as a shift to a more constitutional form of government. Others have even suggested that the privy council, by controlling the flow of intelligence, became the practical head of the regime. In one historian’s view, the way her ministers dominated intelligence circulation diminished Elizabeth’s power, pointing the way to something close to a ‘monarchical republic’.9

This is misleading. Elizabeth was in personal control, engaged in the everyday detail of spy craft, even setting out how particular agents should be rewarded – or how specific suspects might be tortured. She did, however, seek plausible deniability when it suited her.

Elizabeth had to engage directly because there was more than one spy system. In fact, there were at least three rival intelligence systems. Cecil, Leicester and Walsingham, while working together to a degree, ran their own private networks with distinctive styles and their own clientele. This reflected not only rivalry for privilege and patronage, but also deep ideological divides over how to secure the monarchy from subversion.10

Far from being a proto-modern intelligence community, these networks competed at home and abroad, spying on each other and even attempting to undermine each other’s work.11 What is curious is how well this byzantine system, with Elizabeth at its head, worked, despite the fact that intelligence was often a way of gaining favour or smearing court rivals. Elizabeth needed all these spies, but she also found them vexing. Walsingham, the most famous spymaster of the era, was intense, puritanical, obsessive, even paranoid. Perhaps the first to encapsulate the idea of worst-case analysis, he urged: ‘There is lesse daynger in fearinge to muche then to little.’12 Elizabeth, as the old saying goes, needed to watch the watchers.

QUEEN ELIZABETH DID not inherit an intelligence community. Instead, it developed slowly during her first decade on the throne. Succeeding her half-sister in 1558, she enjoyed a decade of relative grace that ended with the arrival of Mary, Queen of Scots, in England. The following year, northern earls unsuccessfully tried to overthrow Elizabeth in favour of her rival, Mary. So began the Elizabethan era of secret intelligence.

The Northern Rebellion was superficially about tensions between Catholics and Protestants at court. Although Elizabeth tried to present a tolerant front, she marginalized important Catholic figures. They, along with several other nobles in the north, revolted in the summer of 1569. By November, several hundred knights assembled in County Durham; open rebellion had broken out. Even Pope Pius V weighed in, declaring Elizabeth a heretic and encouraging defiance.13

On 13 December, Elizabeth’s forces arrived to meet them, and, within a week, the rebel leaders were on the run to Scotland. The rather short-lived revolt signalled the beginning of a long period of spy wars and, with the rebellion over, Elizabeth ramped up her intelligence capabilities. The Northern Rebellion shocked her, for it was not merely a conspiracy of northern barons but, in her mind at least, constituted a popular religious rising.

Elizabeth personally intervened in the reprisals. She asked for more executions of ‘the meaner sort of rebels’ as a deterrent, or, as she put it, for ‘the terror of the others’.14 Her agents executed no fewer than 750 of them. More importantly, Elizabeth, along with her closest advisers, had come to see the threat that Catholicism posed to her rule, and how it combined active external subversion with internal disloyalty. The Northern Rebellion not only transformed how Elizabeth understood her enemies, but also drew her towards new forms of intelligence operations, in particular the use of elaborate covert operations, even provocation and entrapment; much of it focused on her captive Catholic rival, Mary, Queen of Scots.15

IN 1571, THE somewhat fanciful Ridolfi Plot again underlined that Elizabeth was no mere bystander when it came to intelligence operations. Roberto Ridolfi was a gregarious Florentine banker based in London, who had links to the Cecils and even to the queen herself. Seemingly respectable, he travelled Europe on business without suspicion, moving effortlessly between Amsterdam, Rome and Madrid.

During his travels, Ridolfi quietly built up support for an invasion of eastern England which, he hoped, would stimulate a Catholic revolt. This would be followed by Thomas Howard, the duke of Norfolk, marrying Mary, who would then replace Elizabeth as queen.16

No less than her nemesis Elizabeth, Mary also delighted in the pantomime and paraphernalia of spy craft. An English prisoner for almost twenty years, she presided over an elaborate system of couriers, codes and encryption. She was a particularly zealous practitioner of the arcane art of invisible inks, encouraging contacts, ‘under the pretext of sending me some books’, to ‘write in the blanks between the lines’.17 Unfortunately for Mary, most of her correspondence, whether disguised by cyphers or invisible ink, was available to Elizabeth’s spymasters throughout her captivity.

For Walsingham and Cecil, the Ridolfi Plot offered a wonderful chance to act against Norfolk, among the wealthiest men in the country. In April, they detained one of Mary’s servants at Dover. An inspection of his luggage unearthed forbidden texts and enciphered letters. Later, deep in a dungeon inside the Tower of London, he was placed on the rack and blurted out enough to bring in one of Mary’s closest advisers, the bishop of Ross, and the duke of Norfolk.18 The rack was such a fearsome limb-dislocating device that often the mere sight of it caused brave men to buckle. Two of Norfolk’s clerks were rounded up, each caught carrying gold to Mary’s Scottish supporters. Offered a brief opportunity to inspect the rack that awaited him, the first, Robert Higford, quickly told all he knew.

The second clerk, William Barker, refused to confess and was duly tortured. He then revealed that secret documents were hidden in the roof tiles of one of Norfolk’s houses. In this ingenious hiding place, Walsingham found a complete collection of papers connected with Ridolfi’s mission, and nineteen remarkable letters to Norfolk from Mary and the bishop of Ross.19

All was not as it seemed, and even this stash of secret letters did not tell the full story. Ridolfi was effectively one of Elizabeth’s own personal agents who had gone rogue. Like so many figures in the relatively benign first decade of her reign, he had felt safe enough to play all sides. Walsingham had worried about Ridolfi as early as 1569 and had even brought him in for interrogation. Although Ridolfi’s house was turned upside down, Walsingham found nothing incriminating and duly released him. Elizabeth chose her words carefully when he was arrested.20

Because of his excellent mobility and contacts, the queen had in fact used him to secretly explore the chances of compromise with the Continent. As late as October 1570, she seems to have sent him on discreet diplomatic missions to Flanders. More remarkably, in March 1571, Ridolfi held a secret rendezvous with Elizabeth at Greenwich Palace, where he again offered his services. She gave him ‘a very favourable passport’ as her blessing, before despatching him on a secret mission to Rome. This was nothing less than Elizabeth’s backdoor attempt at détente with the papacy. However, Elizabeth had misjudged him and, in urging Walsingham to let him loose, she had simply allowed the slippery Ridolfi to switch sides again.21

Farcical and fantastic though it was, there can be no doubt that the discovery of the Ridolfi Plot had important consequences. Indeed, it rearranged power politics within Elizabeth’s regime: Cecil replaced the executed Norfolk to become the principal person in the Council; meanwhile, Walsingham briefly headed off to Paris, the world centre of espionage, where he refined his skills further.22

Walsingham’s fabled spy system came on quite late, being established only in the mid-1570s, almost two decades after Elizabeth’s accession. He built his network gradually, for his early lack of power and patronage slowed the development of his innovative approach to intelligence. Before rising to be senior principal secretary in 1576, he had lacked the necessary resources and was often little more than a courier between Cecil and his more old-fashioned elite spies of patronage. Walsingham was a relative late-comer, albeit rather more effective and ruthless.23

He became more hawkish than Cecil, advocating wider surveillance together with an aggressive, expansive and technical intelligence-based approach to countering subversion.24

He was more professional, employing people of any class so long as they had the special skills that were now required. He presided over a more scientific kind of spying. Codebreakers, such as Thomas Phelippes, became increasingly important. The supply of intelligence depended on a delicate dance between the talented cryptographers and moles deep in the embassies of France and Spain.

Elizabeth knew all about this. For example, she learnt in 1572 that there were spies in the French embassy who would ‘remain quiet in place’ providing access to secret documents.25 She understood that these deep cover spies had become one of the primary methods of obtaining information during the middle part of her reign.26

ACROSS THE NORTH Sea, the Dutch Revolt against Spanish rule further stretched Elizabethan intelligence. When Dutch Protestants rose up in the mid-1560s, some asked Elizabeth for support. She expressed sympathy for the rebels and knew that Spanish victory would have challenged her Protestant supremacy and enabled King Philip II of Spain to invade southeast England from Dutch deepwater ports. At the same time, she wished neither to provoke the powerful king nor to financially support an expensive insurgency.27

Her initial response was covert action. Elizabeth used a kind of performative secrecy to demonstrate the long reach of her secret services. In 1570, this was achieved through the abduction on the Continent of Dr John Story, underlining that, even abroad, traitors could not escape her wrath.

As a Catholic member of parliament, Story had strongly criticized Elizabeth and supported the Northern Rebellion. Elizabeth already knew that he was one of the foremost opponents of her ban on Catholic books and papist propaganda. Her spies then realized that he had been working for subversive underground Catholic movements. Tipped off about this discovery, and knowing he was in imminent peril, he escaped to the Spanish Netherlands, confident that King Philip would grant him asylum alongside some of the leaders of the Northern Rebellion.

He was wrong. Queen Elizabeth approved a successful operation to abduct him and bring him back to England for trial. On 1 June 1571, he was executed at Tyburn gallows by being hanged, drawn and quartered. Not only was this an early example of ‘rendition to justice’, but it also showcased Elizabeth’s secret strength to her foreign counterparts.28

Meanwhile, and despite some initial success, Spain’s heavy-handed response to the insurrection only inflamed local violence further. Elizabeth’s advisers emphasized the importance of plausible deniability when supporting the rebels. As early as 1562, her ambassador to France argued ‘the more expedicion and the more secrecie that is used in this, the better it will prove for all respectes. The Queen’s majestie and you of her councel muste be ignorant of this matter.’29

Elizabeth approved a range of covert measures or, as Cecil put it, ‘covert meanes’ to aid the rebels. She turned a blind eye to the recruitment of English soldiers fighting alongside the local Protestants. She secretly sent William of Orange, leading the revolt, a few hundred soldiers alongside a subsidy of around 300,000 florins. The message was clear – if deniable. Zealous Protestants knew they were fighting with Elizabeth ‘as it were but winking at their doings’.30

In 1578, the queen covertly and grudgingly sent a further one million florins – and a mercenary army. Although she loathed spending the money, she knew that covert action was less expensive and less provocative than open warfare. In 1581, with the situation continuing to deteriorate, she tried to work through the French, sending the duke of Anjou, her one-time suitor, secret financial assistance in his attempts to counter the Spanish. At numerous points, perhaps to maintain secrecy, Elizabeth fought to make sure that the Dutch cause was not taken up in the English parliament.31 She had grown so used to covert operations that Walsingham accused her of finding it difficult ‘to enter into the action otherwise than underhand’.32

All the while, Elizabeth attempted to present herself as neutral to Spain. She duplicitously tried to assure King Philip that she stood aloof from the rebels who had ‘solicited [her] to take possession of Holland and Zealand’ and that ‘he never had such a friend as she had been’.33

ON THE DOMESTIC front, Walsingham enjoyed success in tackling subversion by launching elaborately offensive counter-intelligence operations. The Catholic plots of this era were certainly real, but they were often dreadfully naïve, allowing Walsingham to manipulate their efforts from the outset. In the past, the authorities would have swooped on any plotters immediately, but Walsingham’s new approach to espionage involved playing a longer game to win bigger prizes. In the short term it allowed him to justify a more zealous anti-Catholic approach and in the long term it generated enough evidence to secure his ultimate ambition: Mary’s execution.34

He enjoyed numerous intelligence successes using a combination of undercover agents inside foreign embassies, torture and intercepting communications, to protect Elizabeth and incriminate Mary. Despite this, the queen’s relations with him were never good. By equal turns she found him both indispensable and obnoxious. He was at the height of his powers between 1581 and 1586, rooted in Elizabeth’s regime as a technical bureaucrat. Yet Elizabeth hesitated to give her favour with the same enthusiasm as she had to Cecil or to Leicester. Elizabeth nick-named Leicester her ‘eyes’ because she valued his watchfulness. She never tried to hide her opprobrium or hostility towards Walsingham. In March 1586, she even threw a slipper in his face when she discovered he had been downplaying the threat of the Spanish navy allegedly assembling at Lisbon in order to avoid resources being spared from the campaign in the Low Countries. Elizabeth knew that to allow Walsingham alone to control intelligence was to surrender too much power.35

JUST LIKE RIDOLFI, William Parry was another Elizabethan agent gone rogue. Over a period of three years he morphed from being a loyal spy for England into a spy willing to assassinate the queen herself.

Studying law but mired in debt, Parry joined Cecil’s band of noble spies watching Catholics in Europe, but mostly with the hope of fleeing his creditors. Moving backwards and forwards between London and Rome, he passed intelligence over to Cecil, but was secretly drawn towards Catholicism. In 1580, when briefly in London, he assaulted one of his creditors and was sentenced to death. Elizabeth stepped in to pardon him, suggesting that he was still a valuable agent.

Two years later, on another sojourn to the Continent, Parry seems to have become a double agent, going over to the Catholic side and seeking approval in France and Italy for an assassination scheme. Returning to England in 1584, he sought to become an elaborate triple agent. He disclosed some of his dealings to the queen, claiming to have acted only to provide cover to Protestant espionage. Astonishingly, Elizabeth not only pardoned him, but also rewarded him with a seat in parliament and a sizeable income.

It was not enough. Still plagued by debts, Parry attempted to manufacture one more plot to be ‘discovered’ in the hope of yet greater rewards. He approached another conspirator, Sir Edmund Nevylle. The two plotters came up with diverse and creative ways to despatch Elizabeth, from riding up to her coach and shooting her at point blank range to killing her during a private audience. They settled upon stabbing her in a private garden in Whitehall Palace.

By February 1585, they were ready. Unfortunately for Parry, Nevylle started to have doubts and informed against his fellow conspirator. Regardless of whether or not Parry had actually intended to kill Elizabeth or whether he had intended to expose Nevylle and bolster his own standing, he quickly found himself in the Tower of London facing execution for high treason. He wrote a full confession to the queen and sent letters to Cecil and Leicester.36 Perhaps in the hope of pardon, he pleaded guilty at his trial, but subsequently declared his innocence, insisting that his confession was a tissue of falsehoods.

The outcome of all this twisting was predictable. Parry was executed on 2 March in Westminster Palace Yard. On the scaffold he again declared his innocence and appealed to the queen for more lenient treatment of her Catholic subjects.

Also implicated was Thomas Morgan, an adviser to Mary. Walsingham swiftly arrested him, getting closer to the elusive prize of Mary herself. While Walsingham moved in on Mary, Cecil focused his attention on her allies. He placed ever greater numbers of spies within the French and Spanish embassies in order to better investigate the correspondence between Mary and these ambassadors.

THE BABINGTON PLOT of 1586, which led to the execution of Mary, formed one of the darker episodes in Elizabethan intelligence. The intricate scheme to counter it was so highly secret that Walsingham made ‘none of my fellows here privy thereunto’, except for Leicester.37

Anthony Babington was a recusant English gentleman who, like those before him, wanted to replace Elizabeth with Mary. Walsingham uncovered the plot and this time offensively used it to entrap, and finally remove, Mary. He created, and secretly controlled, a channel of communication to and from the unsuspecting Mary. She thought her incriminating letters were secure but Walsingham’s agents, who had infiltrated her circle and helped establish the channel, ensured that they were decoded and made their way back to him.38

The deciphered messages implicating Mary piled up. Walsingham turned his evidence over to Cecil, a more impeccably respectable adviser and better placed to present the case against Mary to the queen. On 8 October 1586, faced with overwhelming evidence, Elizabeth gave her agreement to ‘authorize them to use their discretion respecting the manner of first communicating with the queen of Scots; also in respect to any private interview with her if she should require it’. Mary was arrested and awaited trial for treason.39

Again, Elizabeth was in charge. Although she condemned Leicester and Walsingham as ‘a pair of knaves’, and distanced herself from the execution, her concern was more with the public spectacle than the private reality. She had explored the possibility of Mary’s assassination, or perhaps being met with some unfortunate accident, several times. Walsingham understood the queen’s views. In a letter to one of his contacts, he expressed Elizabeth’s disappointment that ‘you have not in all this time… found out some way to shorten the life of that queen’.40

MARY’S EXECUTION PRECEDED a wider round of international conflict. Elizabeth retaliated against King Philip by escalating support for the Dutch Revolt against Spain, as well as funding privateers to raid Spanish ships across the Atlantic. Spain had to respond and, by 1587, Walsingham’s spies reported that the Armada was ready to sail.

As over a hundred Spanish ships prepared to depart, Elizabeth’s attention turned to deception. For this she needed another kind of network. Cecil ran an alternative spy system based around English Catholics exiled on the Continent. Its main focus was Edward Stafford’s embassy in Paris which competed with Walsingham’s spy network, searching for Catholic intelligence that would benefit their patrons in policy debates back home.41

Stafford’s mission in Paris infuriated Walsingham. He thought it was all too close to Catholicism and he was deeply suspicious that Stafford was selling secrets to Elizabeth’s enemies. Meanwhile, Elizabeth and Cecil used Stafford, seemingly the voice of détente, as a channel of deception.

In early 1587, he supplied the Spanish with secrets about a forthcoming expedition by Francis Drake. The detail was remarkable, including the number of ships, who was commanding each vessel, their weaponry and most importantly their destinations. Few at court knew such things.

Stafford’s leak, for which he was bribed the paltry sum of 5,200 crowns, constituted treason.42 But Elizabeth and Cecil had deliberately mixed in false information alongside the accurate intelligence, suggesting the fleet’s destination was either Lisbon or Cape St Vincent. The Spanish bought the deception and had no idea that Drake was actually headed for Cadiz to ‘singe the King of Spain’s beard’.43 This was an intelligence triumph, even if the subsequent defeat of the Armada the following year owed more to fortuitous weather and circumstance.

ELIZABETH PERSONALLY STEERED intelligence. By the mid-1580s, the key meeting seems to have taken place at about 10 o’clock each day. Here, Walsingham briefed the queen in her private chamber, usually verbally, giving her the latest intelligence but also bringing documents for her to sign. He would then return often two or three times during the day, suggesting that Elizabeth was a hands-on and rather demanding intelligence consumer. Walsingham was in increasingly poor health and, as he noted, these meetings ‘maketh me wery of my lief’.44

She knew who her star spies were. Indeed, they were sometimes encouraged to write accounts of their missions for her to read. Typically, Edward Burnham, one of Walsingham’s agents, wrote the story of his operations in France. A racy read, it made both Burnham and Walsingham look good. The queen often granted them a personal pension, normally about £100 a year, in recognition of their special service.

One of the most important spies was Thomas Phelippes, whose codebreaking efforts were central to unravelling the Babington Plot. The queen promised him a position as clerk of the Duchy of Lancaster but to his dismay it never materialized. Walsingham’s secretaries, who were also important to the espionage effort, were rewarded differently, usually with parliamentary seats.45

Elizabeth took a personal – and particularly ghoulish – interest in executions. She pressured Cecil to ensure that the deaths of Babington and his co-conspirators were especially nasty. They had, after all, committed ‘horrible treason’ and she wanted their public deaths to deter others by creating ‘more terror’. Somewhat baffled, Cecil responded that the normal practice of hanging, drawing and quartering was surely ‘as terrible as any other device could be’. But Elizabeth urged that their bodies be torn into little pieces afterwards. She also had them executed on specially constructed gallows at St-Giles-in-the-Fields, the place where the plot had first been concocted. She was determined to make her point.46

Elizabeth also seems to have taken a keen interest in interrogation techniques and corresponded personally with her chief torturers. The most fearsome was Richard Topcliffe, a zealous and persistent hunter of fugitive priests. A forensic reader of Catholic books, he might be regarded as a pioneer of ‘open source’ intelligence practice.47 Rather like Walsingham, he was a free-booting, self-financed operator with his team of ‘instruments’, and, while he worked with both Cecil and Walsingham, he always considered himself the queen’s personal servant and friend.

‘You know who I am?’ Topcliffe rhetorically asked his victims, revelling in his reputation. ‘I am Topcliffe! No doubt you have often heard people talk about me?’ A perverse sadist, he sometimes boasted to his prisoners of being physically intimate with the queen, almost certainly a bizarre fantasy, before following them to the gallows to observe ‘God’s butchery’. Undoubtedly, he knew the queen well and, as late as 1592, was writing to her about special techniques to be used on particular individuals. After he was imprisoned for extorting money from some of his wealthy victims, the queen had him quickly released.48

ELIZABETH’S INTELLIGENCE SYSTEM looked impressive, but it was deeply precarious. She oversaw a mess of competing networks, private interests and questionable loyalties. Most importantly, intelligence was desperately underfunded.

The queen was notoriously parsimonious, and spying was costly. She left poor Walsingham to bridge the gap personally. To help cover his costs, the queen granted him various sinecures, including the Duchy of Lancaster. The biggest earner was granted prior to the Babington Plot, a royal patent covering the customs of all the important western and northern ports from August 1585, bringing in an annual sum of £11,263. Walsingham kept more than half of this money. Elizabeth grudgingly recognized his professionalism, for while Cecil and Leicester spent their cash on impressive residences, Walsingham dutifully ploughed most of his income back into ever more elaborate systems of espionage.

Elizabeth did provide some money directly for espionage, but it was not remotely enough. She saw intelligence as a short-term panacea rather than the construction of a long-term system, still less a proto-modern intelligence community as some have suggested. In 1585, she allowed only £500, rising to £2,100 in 1586, as a response to the Babington Plot. The panic before the Spanish Armada represented a high-water mark at £2,800. But it was sharply cut soon afterwards.49

On his death in April 1590, Walsingham had large debts. Despite state subventions, his zealous spying activities had outrun his own resources. Moreover, because he had no male heirs, his personal system collapsed. By contrast, Cecil passed his old-style network of gentlemanly spies down to his son. With this change, Cecil’s political pragmatism and softer approach had eventually triumphed over Walsingham’s intense Protestantism.

Given the rapid collapse of Walsingham’s intelligence system, it was perhaps just as well that Elizabeth’s last decade was the quietest. The absence of top spies frustrated the queen, though, and she even turned to Thomas Phelippes, Walsingham’s star codebreaker who had since ended up in debtors’ prison. Both she and Cecil unfairly complained about the fact that, from his cell, he now seemed to take longer over his work.50 Towards the end of her reign, one lawyer lamented that the ghost of Sir Francis Walsingham ‘groaned to see England barren of serviceable intelligence’.51

2

POPISH PLOTS AND PUBLIC PARANOIA

‘every man who does not agree with me is a traitor and a scoundrel’

George III1

EVEN BEFORE QUEEN Elizabeth died, an ‘intelligence group’ planned her succession. It consisted of half a dozen influential figures, including Robert Cecil, who corresponded secretly and identified each other only by a number. Childless, Elizabeth was succeeded in 1603 by James, the son of Mary, Queen of Scots. The new king, known as James I in England, kept the younger Cecil on as his first minister.2 Robert Cecil had succeeded his father as Queen Elizabeth I’s lord privy seal and remained in power during the first nine years of King James I’s reign until his death. If there was any continuity with sixteenth-century espionage it was with the Cecils’ network of gentlemanly spies.3

Over the following two and a half centuries, monarchs directly shaped the ebb and flow of secret intelligence. Some, like Elizabeth, enthused about spy craft; others showed little interest at all. James fell into the latter camp. He and his immediate successors surrounded themselves with pampered favourites and flamboyant chancers rather than intelligence professionals.4 To be fair, he had less need for secret intelligence after rapidly signing a peace treaty with Spain. In an instant, many of the Catholic plots which plagued Elizabeth became impotent without Spanish support. Whether interested in intelligence or not, James and many of his successors preferred propaganda to a more professional use of espionage. Some would ‘blow’ hard-earned codebreaking successes to achieve a quick public victory; others would stoke conspiracy over facts.

THE GUNPOWDER PLOT of 1605 was an important exception: a Catholic plot that was far from impotent. Despite the king’s disinterest in intelligence, Cecil maintained an active network of agents in the form of ‘false priests’ and continued to gather intelligence through embassies, but the days of Walsingham’s ferocious surveillance were long past. King James received no hint of the plot. Although the plotters have been represented as anti-Protestant, they were perhaps even more anti-Scottish.5

Fortunately for the king, the plotters’ ambition proved their downfall. They had hoped to accompany the assassination of James with an insurrection and widened their network accordingly to wealthy families in the Midlands, especially in Northamptonshire, whom they hoped would rise up in the wake of the attack. Uprisings are always difficult to conceal and, sure enough, some of these families worried for the safety of their relatives in parliament who might be literally sitting on top of the explosion. Relatives alerted relatives – and one such warning reached Cecil on 1 November. He took it to the king.

Unimpressed that the plot was so advanced, James took personal control of events. He was clearly capable of action. Five years earlier, he had responded with unprecedented ferocity against a conspiracy to overthrow him. Two aristocratic brothers had lured him to a country house at Perth under the pretence of having found a treasure trove. After dinner, when James went upstairs to bed, one of the brothers pulled out a knife, held James hostage and called for the other to join him. The king stuck his head out of the turret window and shouted, ‘Murder! Treason!’ His courtiers rushed up to find the first brother dead. The second pulled his own knife but was quickly killed. James had been personally duped and clearly lacked any intelligence of the plot. Afterwards, he confiscated their property and insisted that their dead bodies be hanged, drawn and quartered.6

Now, James did not want to make the same mistake again. Adopting a watch and wait strategy, he waited until 4 November to conduct the first search in the hope of catching the conspirators late in the preparations. All he found was a pile of firewood inside one of the cellars underneath parliament.

Still suspicious, James ordered a second search. It famously uncovered thirty-six barrels of gunpowder under the firewood and netted Guy Fawkes. Brave to the last, Fawkes told James to his face that he planned to blow him ‘back to Scotland’ and resisted giving up the names of his fellow conspirators despite being tortured in the Tower.

Nevertheless, Fawkes’s network was rolled up; its leaders hunted, tortured and killed. Addressing parliament afterwards, James claimed personal credit for thwarting the plot and, although he had gone to some lengths to ‘big’ this up, it was not without foundation.7

The Gunpowder Plot was culturally important. By the 1620s, the population had been fed a constant diet of conspiracies for decades, contributing to an abiding climate of paranoia. If it was not Protestant stories about ‘popish plots’ then it was Catholic rumours of evil counsellors. These conspiracy theories reached their apogee in the early Stuart period with the mysterious demise of James.

The king had chosen George Villiers as his key adviser. Goodlooking and swashbuckling, but a poor manager of political affairs, he was certainly no Walsingham.8 When James grew ill and died in 1625, suspicion fell on the man who had administered his final treatment: Villiers. Courtiers whispered that he had poisoned the king to hasten the promotion of his friend and James’s heir, King Charles I.9

Villiers’ speedy rise, combined with the early death of some of his aristocratic rivals, increased suspicion further.10 In a world where forensic science barely existed, the administration of poison was a popular tool of assassination. The conspiracy theory caught the tide of current fashion and gained credibility by complementing the popular narrative about Villiers and Prince Charles. The pair had grown close during James’s reign, with Villiers even joining him in disguise on a secret mission to win the hand of the Spanish princess, thus sealing the king’s policy of détente. They bonded closer when the mission failed, uniting them in a distaste for all things Spanish. The young pair excluded the ageing monarch, who increasingly lost interest in matters of state and became resentful and suspicious towards them.11 Villiers was an opportunist and, conscious of his rapidly deteriorating relationship with James, joined Charles in pushing for war with Spain.12

Whatever the truth, the rumours would not go away. Factions across the political spectrum hated Villiers and seized upon the story. Print had become cheaper and, in the era of the political pamphlet, scandal sheets circulated far and wide. The conspiracy undermined the parliament of 1626 and almost certainly led to the assassination of Villiers two years later at the age of just thirty-five.13

The propaganda, whether true or not, had catastrophic consequences. At the beginning of the first English Civil War, parliamentarians skilfully exploited the belief that Charles I was an accessory to his father’s death. It helped to discredit the king and would surface again during his trial. Indeed, it became almost a founding myth of Cromwell’s republic, debated furiously by each faction down the decades.14

Elizabeth’s complex competing spy empire was long gone, but this sea of rumour and propaganda was to some extent the backwash of her personal approach. She had stoked public paranoia about spies and plots to a remarkable degree and turned public executions into spectacles in the hope of creating more terror. It is not surprising that espionage, conspiracy and rumour, mixing myth and reality freely, featured so prominently in early Stuart England. This murky climate shaped how the king approached intelligence at the onset of civil war.

THE CIVIL WARS between royalists and parliamentarians – what is now often called the War of the Three Kingdoms – resulted in the defeat and execution of Charles I and the eventual restoration of his son, Charles II, interspersed by the temporary republican rule of Oliver Cromwell. The scale of death and destruction was remarkable, certainly well beyond that of the First World War, casting a long shadow that lasted more than a hundred years, shaping politics well into the middle of the eighteenth century.15

Like his father, Charles I did not embrace secret intelligence. In fact, his closest adviser openly expressed disdain for espionage, rejecting the use of spies and adamantly refusing to intercept the correspondence of Charles’s opponents. Such underhand activity was too ungentlemanly. The king did maintain a secret service budget, but, as was often the way, he spent most of it on propaganda.16 In a world where perceptions often mattered more than truth, Charles desperately lacked a Cecil, still less a Walsingham, to control and direct secret activities.17 Even when underground networks of royalist exiles mobilized on the Continent, weaknesses in the king’s organization and his reliance on inexperienced favourites fatally undermined their espionage capability.18

Parliamentary leaders also lacked a sophisticated intelligence system. Like Charles, they never recreated the complex edifice erected under Elizabeth. They did, entirely fortuitously however, recover one of its key elements: cryptography.

John Wallis, a Cambridge-educated mathematician, was accidentally drawn into the world of cryptography during a dinner party. A guest who happened to be a senior parliamentarian whipped out an intercepted letter written in cypher as a curious talking point. He asked, half in jest, whether Wallis could make anything of it. To his surprise, Wallis responded, ‘Perhaps I might.’ After dinner, he successfully deciphered the code.19

What it contained was sheer dynamite. Confirming the parliamentarians’ worst fears and suspicions about Charles, the letter showed that he had been trying to raise an army of Catholic soldiers from Ireland to invade England, as well as negotiating help from French and Spanish mercenaries – all of them also Catholic. They published the letter widely, presumably blowing the ability to read the cypher in the process and again showing the seventeenth-century preference for propaganda over cryptography. Queen Elizabeth, who understood the value of codebreaking, would never have done this.

As the grip of the English parliamentarians tightened, royalists resorted to disguises and elaborate plots. Many of these failed but notably one did succeed: the fourteen-year-old duke of York, and future King James II, disguised himself as a girl and caught a boat to Europe. The king attempted secret escape plans of his own, but by contrast these failed.20

On 30 January 1649, Charles I was beheaded in London. Endless paranoia about plots, some far-fetched, finally seemed to be confirmed by deciphered letters in Charles’s own hand. Britain was now ruled by a commonwealth, although committed royalists remained loyal to his exiled son, the future Charles II.