19,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

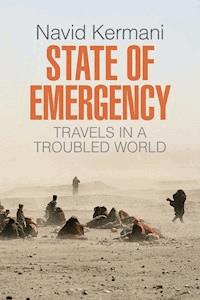

This book ventures into the world beyond Lampedusa: the crisis belt that stretches from Kashmir across Pakistan and Afghanistan to the Arab world and beyond, to the borders and coasts of Europe. Celebrated author Navid Kermani reports from a region which is our immediate neighbour, despite all too often being depicted as remote and distant from our daily concerns. Kermani has visited the places where no CNN transmitter truck is parked and yet smouldering fires threaten world peace. In his widely praised, wonderfully agile and careful prose, he reports on NATO's war in Afghanistan and the underside of globalization in India, on the civil war in Syria and the struggle of Shiites and Kurds against the 'Islamic State' in Iraq. He was the only Western reporter present at the suppression of the mass protests in Tehran, travelled with Sufis through Pakistan, talked with Grand Ayatollah Sistani in Najaf, and observed the disastrous Mediterranean refugee route in Lampedusa. Kermani's gripping reports allow us to understand a world in turmoil, to share the suspense and the suffering of the people in it. As if by magic, he brings individual lives and situations to life so vividly that complex and seemingly distant problems of world politics suddenly appear crystal clear. Our world too lies beyond Lampedusa.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 403

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Copyright

EDITORIAL NOTE

CAIRO, DECEMBER 2006

PARADISE IN A STATE OF EMERGENCY: KASHMIR, OCTOBER 2007

HOUSEBOAT 1

IN THE CITY

HOUSEBOAT 2

POLITICIANS 1–4

NIGHT

HOUSEBOAT 3

THE SHRINE

HOUSEBOAT 4

IN THE COUNTRYSIDE

HOUSEBOAT 5

THE MOTHER

HOUSEBOAT 6

AHAD BABA

IN KASHMIR, FAR AWAY FROM KASHMIR

LANDLESS: BETWEEN AGRA AND DELHI, SEPTEMBER 2007

LUMPENPROLETARIAT IN FORMATION

WHY COMPLAIN?

THEY WANT LAND

EXPULSION AS INDUSTRIAL DEVELOPMENT POLICY

THE SKY AND THE GROUND

RAM PAYDIRI DOESN’T UNDERSTAND

THE LABORATORY: GUJARAT, OCTOBER 2007

AN IDOL

ON THE RUBBISH TIP

INTO THE CENTRE

SOCIAL PRAXIS

INDIA’S FUTURE

WHERE EVEN THE ATHEISTS PRAY

THE PIT

A VISIT TO THE SUFIS: PAKISTAN, FEBRUARY 2012

RHYTHM OF GOD

WAR AGAINST THEMSELVES

THE LOVERS’ TOMB

O PAPA, PROTECT ME

IN THE MANSION DISTRICT

THE POOR PEOPLE’S PEACE

QUIET, CLEANLINESS AND ORDER

THE FEAST

THE COSMIC ORDER

BLEAK NORMALITY: AFGHANISTAN I, DECEMBER 2006

PEOPLE DON’T CHANGE MUCH

REALLY CRAZY

TWO BRITISH COMMANDERS

HUMANITARIAN MISSION

IN KABUL

WHERE IS THE PROGRESS?

MASTER TAMIM

THE NEW MOTORWAY

AMERICAN HEADQUARTERS

VISIT TO THE PASSPORT OFFICE

COLA IN THE DARK

THE LIMITS OF REPORTING: AFGHANISTAN II, SEPTEMBER 2011

CEMETERY 1

WALLS IN FRONT OF WALLS

NORTHWARD

MAZAR-E SHARIF

THE BEST PLACE IN TOWN

IN THE COUNTRYSIDE

IN THE PANJSHIR VALLEY

IN THE SOUTH

PEACE CONFERENCE

TRIBAL LEADERS 1

KANDAHAR

TRIBAL LEADERS 2

THE LIMITS OF REPORTING

CEMETERY 2

THE UPRISING: TEHRAN, JUNE 2009

CHANCE COMPANIONS

ARRIVAL

WEDNESDAY

THURSDAY

FRIDAY

BACK TO SATURDAY

SUNDAY

EARLY MONDAY

WHEN YOU SEE THE BLACK FLAGS: IRAQ, SEPTEMBER 2014

I NAJAF: IN THE HEART OF THE SHIA

UBIQUITY OF DEATH

A DANGEROUS TOPIC

A DIFFERENT SHIA

WITH SWORDLIKE INDEX FINGER

GRAND AYATOLLAH SISTANI’S MESSAGE

II BAGHDAD: THE FUTURE IS PAST

A THIRTY YEARS’ WAR AND MORE

A HOOKAH WITH GOETHE AND HöLDERLIN

FOG OF MELANCHOLY

RIGHT OUT OF ALI BABA

THE LAST CHRISTIAN

A WARRIOR

III KURDISTAN: THE WAR FOR OUR WORLD TOO

LITERALLY OVERNIGHT

WHAT FOR?

TO THE FRONT

THE GENERAL

THE ENTRANCE TO HELL: SYRIA, SEPTEMBER 2012

THE CENTRE AND THE MARGINS

ARTISTS OF THE REVOLUTION

TWO VIEWS

OUTSOURCING TERROR

THE FEAST OF ST ELIAN

AT THE TOMB OF IBN ARABI

THINKING WITHOUT GRADATIONS

THE INTENSIVE CARE UNIT

THOSE WHO CAN READ, LET THEM READ

WE TOO LOVE LIFE: PALESTINE, APRIL 2005

IN SEARCH OF PALESTINE

WITHOUT HOPE

THE WALL AGAINST EMPATHY

MY CAPITULATION

THEY ARE HUMAN BEINGS

LIFE AS WHAT IT IS: LAMPEDUSA, SEPTEMBER 2008

SUNDAY OUTING

GHOSTS

MIDNIGHT

THE PREVIOUS MAYOR

THE CAMP

THE NEW MAYOR

NIGHT AGAIN

WITH OR WITHOUT APPROVAL

CAIRO, OCTOBER 2012

End User License Agreement

Guide

Cover

Table of Contents

Begin Reading

Pages

iii

iv

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

158

159

160

161

162

163

164

165

166

167

168

169

170

171

172

173

174

175

176

177

178

179

180

181

182

183

184

185

187

188

189

190

191

192

193

194

195

196

197

198

199

200

201

202

203

204

205

206

207

208

209

210

211

212

213

214

215

216

217

218

219

220

221

222

223

224

225

226

227

228

229

230

231

232

233

235

236

237

238

239

240

241

242

243

244

245

246

247

248

249

250

251

252

253

254

255

256

257

258

259

261

262

263

264

265

266

267

268

269

270

271

272

273

274

275

277

278

279

280

281

282

283

284

285

286

287

288

289

290

291

292

293

294

295

296

297

298

299

STATE OF EMERGENCY

TRAVELS IN A TROUBLED WORLD

NAVID KERMANI

TRANSLATED BY TONY CRAWFORD

polity

First published in German as Ausnahmezustand: Reisen in eine beunruhigte Welt © Verlag C. H. Beck oHG, Munich, 2016

This English edition © Polity Press, 2018

11 maps © Peter Palm, Berlin/Germany

The translation of this work was supported by a grant from the Goethe-Institut.

Polity Press65 Bridge StreetCambridge CB2 1UR, UK

Polity Press101 Station LandingSuite 300Medford, MA 02155, USA

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purpose of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

ISBN-13: 978-1-5095-1474-8

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Names: Kermani, Navid, 1967- author.

Title: State of emergency : travels in a troubled world / Navid Kermani.

Other titles: Ausnahmezustand. English

Description: Cambridge, UK : Polity Press, 2018. | Translation of: Ausnahmezustand : Reisen in eine beunruhigte Welt. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017036533 (print) | LCCN 2017039888 (ebook) | ISBN 9781509514748 (Epub) | ISBN 9781509514700 | ISBN 9781509514700 (hardback) | ISBN 9781509514717(pbk.)

Subjects: LCSH: Kermani, Navid, 1967---Travel. | Middle East--Description and travel.

Classification: LCC DS49.7 (ebook) | LCC DS49.7 .K44513 2018 (print) | DDC 915.604--dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017036533

The publisher has used its best endeavours to ensure that the URLs for external websites referred to in this book are correct and active at the time of going to press. However, the publisher has no responsibility for the websites and can make no guarantee that a site will remain live or that the content is or will remain appropriate.

Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition.

For further information on Polity, visit our website: politybooks.com

EDITORIAL NOTE

The reports in this book originally appeared, in much shorter versions, as newspaper and magazine articles in the Neue Zürcher Zeitung (Afghanistan I), the Süddeutsche Zeitung (Pakistan), die tageszeitung (Palestine), Der Spiegel (Iraq) and Die Zeit (all other chapters). I thank the editors and the archives of those publications, especially Die Zeit, and my editor Jan Ross, for their encouragement, support and advice. I would also like to thank the Goethe Institutes in Ramallah, Jerusalem, Karachi and Cairo, the Goethe Centre in Lahore and the Konrad Adenauer Foundation in Cairo, which invited me to give readings and lectures. All the other trips were taken on assignment for the publications named.

The travelogues written between 2006 and 2009 have become part of the novel Dein Name (published by Hanser, Munich, 2011).

I thank my editor Ulrich Nolte at C. H. Beck for his excellent collaboration over many years, most recently on this book.

CAIRO, DECEMBER 2006

The tea house where I was the youngest of the regulars, twenty years ago, has expanded but lost none of its charm. To be exact, a few more plastic chairs have been set out in the narrow alley between two sooty colonial buildings, nothing more; but, in this place, just moving some furniture is a cultural revolution. Because any natural sense of taste seems to have died out in Cairo three, four decades ago, progress mostly takes the definition Adorno gave it: preventing progress. Around one, two o’clock, the tiredest whores in Cairo are sure to turn up for a last cola or a first client, while Umm Kulthum sings, as every night, of ‘those days’. The enchantment of the tea house, like that of every hostelry worthy of the name anywhere in the world, consists in the fact that nothing matches and therefore everything, as chance would have it, goes together: the furnishings and the decor, which must have been shabby already when the place opened; the cordial staff who nonetheless overcharge; the most artistic Arab orchestras from the most excruciating loudspeakers; the men regressing to little boys over card and board games; the women likewise acting as if they were still young; and, most of all, the laughter, the loud, chortling, jangling, squeaking, hoarse, malicious, self-effacing, gloating, roguish, jolly, forgiving laughter that is heard more often in Cairo than in any other city, and nowhere in Cairo more often than in the tea house in the evening, and, fortunately, still heard today, I must record, for I am always afraid until I return that the demon responsible for it all may have vanished. An entry in a travel guide could be the end of it, or a notice in the newspapers by one of the new zealots nostalgic for something that never existed – prostitution is among Cairo’s traditions, but not puritanism. There is no way that a symphony like the tea house could be composed today. And of course it never was composed; it was simply there, already a relic on its opening day. All the guests gather and pose for a group portrait, together with the staff and the neighbourhood’s shopkeepers, for a daughter eager to take a picture with her birthday present. Then the head waiter takes a picture of father and daughter that by itself is worth the twenty-year journey.

PARADISE IN A STATE OF EMERGENCY

KASHMIR , OCTOBER 2007

HOUSEBOAT 1

The Paris Photo Service, whose assortment features Kodak film, rows by. Although the sun is shining, the mountains look as if God had dipped them in milk and hung them up to dry. Next comes a shikara, as the gondolas are called in Kashmir, bringing groceries to the houseboat that was recommended to me by my local friends. And in fact it is clean and comfortable, in the British colonial style, like all of Srinagar’s eight hundred floating guesthouses, with heavy, dark furniture, oriental rugs, massive armchairs, although it is oriented towards Indian rather than Western tourists because it is close to the city, where Dal Lake is no wider than a river. As a result, the promised experience of silence, space and snow-covered mountains mirrored in the water turns out to be rather less than majestic. I have a view of cars and rickshaws, multi-storey office buildings of bare concrete, and a hill with a television antenna on top. The Indians seem to find the hundred yards that separate us from the noise of the traffic more than enough. But I, against my best intentions, was slightly disappointed, especially since the evenings on the veranda of the houseboat are so cold that I crawl back indoors and under my blanket to write.

Nevertheless, I am gradually discovering more and more advantages of the situation I have landed in. The boat belongs to a family with deep local roots whose thirty-two members can always find exactly what I happen to need and can supply the full spectrum of opinions, demands and desires that Srinagar has to offer, in addition to a driver, a change of travel reservations, a SIM for my mobile phone. My Indian SIM doesn’t work here for security reasons. To get a new prepaid SIM, you have to have a fixed abode and the approval of the army. Now the boat owner’s niece will have to do without her phone for a few days. She doesn’t seem to use it much anyway – there are no contacts stored on her SIM except the service numbers that came with it: Astro Tel, Dial a Cab, Dua (prayers), Flori Tel, Food Tel, Horoscope, Info Tel, Movie Tel, Music Online, Odd Jobs, Ringtones, Shop OnLine, Travel Tel, Weather. For a city at war, where hardly a street lamp is lit in the evening, the offerings are stupendous. After almost twenty years in a state of emergency, Kashmir has long since grown accustomed to it.

The division of the Indian subcontinent has torn open many wounds: a million people dead, 7 million driven from their homes. Kashmir is one of these wounds that never seems to heal: heavenly Kashmir of all places, whose glaciers, lakes and meadows enchanted more than just poets and voyagers, unfortunately. Foreign rulers had been conquering the valley since the fourteenth century, exploiting it, and often buying and selling it. After the withdrawal of the British in 1947, the larger part of the province fell to India, in spite of its predominantly Muslim population; the west fell to Pakistan; a strip in the northeast was later claimed by China. India promised the United Nations to hold a referendum in which the Kashmiris would decide their own fate. That has not yet come to pass; instead, three wars with Pakistan have. Delhi did accord the province a high degree of autonomy, but in 1989, after a series of patently fraudulent regional elections, an armed rebellion broke out which has since cost hundreds of thousands of people their lives – among a population of 5 million. The Indian army is said to have stationed some 600,000 soldiers in the province, most of them in the Kashmir Valley, which is barely twice the size of Luxembourg. There is no remotely comparable concentration of troops anywhere in the whole world. There are soldiers everywhere, in every city, in every village, on the main roads and the side roads, the high streets, the lanes and even the tracks between the fields, then in the fields themselves, and of course on the lakeshore across from me, one every fifty yards. To the Indians, it is a war against terror. To the local people, it is an occupation.

IN THE CITY

Dead zones interrupt all phone calls near a military facility – if you’re driving, that happens every three minutes. Otherwise, except for the soldiers everywhere, you would never notice during the daytime that Srinagar is at war. But is this war? The army itself, which is not inclined to downplay the danger, sets the number of rebels remaining at about one thousand. The journalists I meet in Srinagar, Indians included, estimate there are a few dozen fighters – at most two, three hundred – plus an indeterminate number of men who work at their jobs in the daytime and at sabotage in the evening. About once a week on average, the newspapers report a skirmish or an attack, often foiled at the last minute. The news agencies issue reports from about eight dead upwards. They write the number of extremists killed, always extremists, whether it is Reuters, AP or CNN. If you read the local press, it is remarkable how many extremists carry address books with them neatly listing the names of their accomplices and ringleaders. A few days later, the same newspapers report a wave of arrests, saying the authorities have struck an important blow against terrorism.

The people, all the people I talk to without exception, are fed up with war. ‘Fed up’ is the expression I hear the most often by far. All right, to be honest I hear salamualeikummore frequently, or aleikum salam whenever I surprise someone with the Islamic greeting. ‘Peace be with you’: that has a very peculiar sound in Kashmir. As time goes on it sounds like a supplication, and this is more than just my imagination; it is an inkling that each new person I talk to will tell me once more they have had quite enough of war, they are fed up: with the nocturnal searches, the ID checks; fed up most of all with the arbitrary actions of these foreign soldiers – foreign-looking, too, darker skin, foreign language, foreign religion, foreign food, foreign customs, and looking as if they’re guarding even the chicken coops with their loaded machine guns. Even at the university, the heart of the movement for independence a few years ago, I meet no one who would still be willing to fight: fed up. Everyone supports the demand for self-determination, I am assured by a professor of English who looks about as old as the Indian state, a professor emerita, that is – but what happens the day after? she asks her students. We need to know that beforehand: none of you has told me anything about that. Will other powers intervene? Neighbouring countries, China, the United States? Will this be another Afghanistan? What about people of other religions? What about women? She can’t see a secular Kashmir. One look at the potential leaders of a free Kashmir is enough for her: Islamists. The students are silent. Some of them have founded a magazine, which mainly limits itself to the problems on campus. The whole resistance has shrunk to this, says one of the editors, to these few stapled pages out of the photocopier. Graduating is more important. See that you don’t get involved in politics, their parents warn them, many of whom fought themselves for azadi, as the magic word was in Kashmir in 1989: for freedom.

In 2002, regional elections were held that are said to have been relatively honest. The coalition in Srinagar is at pains to curb the human rights violations of the Indian army and demands that the soldiers return to barracks. The army has already withdrawn from the old city centre with its narrow lanes. I am so surprised to find no uniforms there that I find myself watching for them. And then I do spy the occasional soldier: machine guns slung on their backs, they stroll casually, shop, haggle over prices. The Indian tourists on the other hand don’t seem to feel safe yet in the old centre, which is so picturesque with its stone and wood houses that one expects to see around every corner a troop of Japanese, a German in a sari or an American in shorts. Since the war, however, tea houses and squares where one lingers aimlessly are no longer a part of Kashmiri culture, but the mosques on the other hand are so well frequented as I have seen only in war zones.

HOUSEBOAT 2

Yes, the Indians are back, recognizable by their clothes, their cameras, their dark skin. On my houseboat too an Indian family has checked in, an engineer from Calcutta with his wife, sister and two children. The engineer and I discover we are the same age, almost to the day. Hey, we have to drink to that, he says, and regrets that the houseboats no longer serve alcohol. His views are just as moderate as those of our host – in other words, irreconcilable. To the engineer, Kashmir is a part of India, ‘an integral part, of course,’ he emphasizes. No, in the schoolbooks there is nothing about the founders of the Indian state promising to hold a referendum. So the soldiers know nothing about it? No, they don’t know; you would have to go to university or otherwise concern yourself with history to find the Kashmiris’ cause anything but absurd. India, he says, pumps enormous amounts of money into Kashmir. He pays twice as much for tomatoes in Calcutta as in Srinagar. Kashmiris want peace, every people wants peace – but the terrorism … if it weren’t for the terrorism. The Indian family is going to spend the day in Gulmarg, a skiing town at 9,000 feet. See you this evening. Yes, see you this evening.

The boat owner, an educated man of about fifty, clean-shaven morning and evening, nods to indicate a white building on the bank, a former hotel that the Indian army has commandeered as a barracks. A few days ago two young people were shot there, officially two suicide bombers trying to get in. The boat owner says the young people were brought to Srinagar by the army and executed here. None of the houseboat residents or the local police witnessed anything to do with an alleged attack. In the photos in the newspapers that the boat owner shows me, the faces are disfigured, so they offer no clue as to whether they are Kashmiris or, as the army claims, foreigners. In any case, the boat owner is convinced they were not suicide bombers, but prisoners. The government of Kashmir, he says, is putting pressure on the army to give up the hotel and reduce its presence in the city. The army is presenting its kind of evidence that terrorism is still a threat to the state.

Between the guests and the hosts I am almost a kind of mediator, trying to elicit understanding sometimes for one position, sometimes for the other. They themselves have nothing more to say to each other – although no unfriendly tones are heard – except when the meals will be ready and where the remote control for the television set is: masters on the one side, not as Indians over Kashmiris, but as guests over the staff, free enough of prejudice to spend their holidays among the rebels; servants on the other side, glad that someone at least is staying on their houseboats again.

POLITICIANS 1–4

Kashmiri politicians who have not gone underground live in their own neighbourhood, separated from the population by roadblocks. If you want to visit the mansions in which the Indian state accommodates them, you first have to pass through several checkpoints. The best-known politicians at least seem to be assigned a whole company of soldiers who bivouac on their park-like grounds, using the garden pavilion as barracks, the tool shed as a field kitchen, the gatekeeper’s lodge for the officers’ quarters. As stylish as the mansions look from the outside, their interiors have all the charm of furnished flats. Of course, to the ordinary people, politicians belong to a caste of their own whose loyalty is richly rewarded by the Indian state. In the mansions themselves, the impression is different. Here the politicians look rather lost amid the furniture that doesn’t belong to them, with soldiers outside their windows, their own city a territory in which they hardly ever set foot – they usually traverse it in a heavily armed convoy.

One politician especially, Yussof Tarigami, chairman of the Communist Party of Kashmir, which tolerates the governing coalition, is convincing in his uneasiness, sitting on the sofa as if he was his own guest, a melancholy man in his fifties with black hair, somewhat too long, parted on the side, who could pass for a police detective in an Italian film. I have no choice, he says. Two years ago he barely escaped an assassination attempt, not his first.

The politicians have little good to say about the state that guards their lives. In the mansions I heard the same accounts of arbitrary arrests, continual humiliation, alienation from India. Violence is on the wane, Tarigami feels, but not because the Kashmiris have reconciled themselves to the occupation: out of exhaustion rather. He himself considered armed resistance wrong from the beginning and decided to carry on the struggle through the institutions. His living in this mansion, yes, a captive, is of course the consequence of having stayed within the system. He too demands self-determination, but points out that the state consists not only of the Kashmir Valley, with its largely Muslim population, but also of Jammu, where the majority is Hindu, and Ladakh, with its many Buddhists. What would happen to them if Kashmir fell to Pakistan? Tarigami asks me, as the English professor asked her students the day before. Independence sounds good, yet a secular, multicultural state is perfectly unrealistic in view of the three giants it would have as neighbours, India, Pakistan, China, none of which would give up its share of Kashmir. There is no perfect solution, Tarigami sighs, and goes on to sketch a plan for a Kashmir that is largely autonomous, though not formally independent, with open borders to the Pakistani part and regional self-government in the three provinces Jammu, Kashmir and Ladakh. That is exactly what the Indian prime minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee and the Pakistani president Pervez Musharraf proposed back in 2003. Vajpayee’s successor, Manmohan Singh, expressed something similar in 2005: not to eliminate the borders, but to make them irrelevant.

‘All we can do is exert pressure, by peaceful means, so that India and Pakistan finally do what they have basically long since agreed on, Tarigami explains. We have to get public opinion in India and Pakistan on our side. We have to show that peace is possible!’

One of the paradoxes of Srinagar is that it is easier to meet with the leaders of the resistance than with political officeholders or with representatives of the military. You simply ring the bell, and sometimes it is the leader himself who opens the door of his house, which is modest, but at least belongs to him. What is still more perplexing, however, is that the resistance leaders are demanding the same thing in principle as the government politicians: autonomy, open borders, withdrawal of the army – the solution sketched out by Hojatoleslam Abbas Ansari is no different.

As a leader of the Shiite minority, the cleric Ansari is one of the spokesmen of the Hurriyat Conference, the umbrella organization of the various resistance groups. The English professor included politicians like him in her warning against Islamists yesterday; Ansari himself assures me he rejects theocracy. Sitting cross-legged, his heels pulled up close under him, an impish smile under his white turban, he moves his hands incessantly as if something suspenseful were about to begin, a match or a game, a coup or a revolution. Perhaps because our conversation is in Persian, he describes the disputes within the resistance with surprising candour. Everyone knows, he says, that the armed struggle is over. The opposition must negotiate in order to stand, perhaps not in the next elections, but in the elections after that. The extremists are not so extreme; they are only insulted that no one has invited them to the table. Make them ministers and you’ll have them on your side.

‘The people say their leaders have sold them out,’ I observe, and I emphasize, ‘all their leaders.’

‘The people are right,’ Ansari answers.

‘That means you have sold them out too.’

‘Yes.’

‘They say the leaders of the resistance have received money from both sides.’

‘True. We leaders of Kashmir have failed, one and all.’

‘You too?’ I ask.

The cleric looks up at the ceiling, as if he would leave it to God to answer that.

If it is a slim majority in Palestine and Israel who know what peace would imply, in this conflict everyone involved knows it: the people, the politicians, the soldiers, the world community – yet for years nothing has happened; there are no more talks, no peace conferences and, since the new Indian-American cooperation, no more international pressure on Delhi and Islamabad. That was different in the 1990s, when the American president Bill Clinton called Kashmir the most dangerous conflict in the world because India and Pakistan both have the atomic bomb. Today India is too strong internationally to have to accept a compromise, and the Pakistani government is too weak domestically to be able to accept one. So peace is limited, for the time being, to a bus that runs once a week between the Indian and Pakistani parts of Kashmir.

Finally I meet a leader who still clings to armed struggle and the goal of an Islamic state. Coincidentally, or perhaps not, Syed Geelani is by far the most charismatic politician Kashmir has to offer, an elegant, older man with a snow-white beard, his cheeks and his upper lip shaven except for a thin moustache. His rectangular cloth cap makes his face look still narrower. Weary eyes, soft voice, good English, clear articulation. Two days before, he was prevented by force from leading Friday prayers – not by the army, but by Kashmiris, the adherents of a rival resistance group which has backed away from the demand for a referendum. Perhaps because he still feels the humiliation, he embraces me, a reporter still asking for his opinion, a few seconds longer than is customary, and silently. When he thinks he sees me shiver, he brings me, although he could just as easily call a servant, a heavy wool blanket from the next room, and one for himself too. Then we sit, bundled up, face to face.

I fully understand Syed Geelani’s position, the wish for self-determination for which he argues persuasively, with unchanging composure and firmness. He describes in detail the atrocities of the Indian army, especially the rapes, a twelve-year-old before her mother’s eyes, then the mother before the eyes of the twelve-year-old, and so on. The problem is that, unfortunately, he is not exaggerating; at most, he is neglecting to mention that the number of assaults seems to be declining. He dismisses as Indian propaganda the accounts which hold the rebels likewise responsible for abuses and murders. From what I know of Pakistan, I think his advocacy of the annexation of Kashmir by Pakistan is, with all due respect, not such a good idea, although I do not phrase it so directly. Geelani radiates such a dignity that one hesitates, as his junior, to contradict him openly. The Pakistanis themselves have dropped the demand for a referendum, I object at last. As if the Pakistanis had had anything to say in the matter, Geelani counters. Not the Pakistanis, but Pervez Musharraf dropped the demand for a referendum: Kashmir, he says, has been betrayed yet again.

A traitor? To the question whether she considers herself an Indian, Mehbooba Mufti answers without hesitation: ‘Yes, of course I am Indian. I am Kashmiri and Indian.’ Whenever a Western television team has found its way to Kashmir in recent years, it has been happy to portray Mehbooba Mufti as a figure of hope: a middle-aged woman, divorced, who, as chairman of the People’s Democratic Party, calls on her people to put down their weapons and, at the same time, raises her voice against the crimes of the Indian army, a diplomatic, Muslim Joan of Arc, religious and feminist. She persuaded many Kashmiris to vote in the last elections and led her party from a standing start into the coalition government. When I visit her in her mansion, she is much more a politician than I had assumed from the reporting: her answers seem prepared in advance, not because they sound implausible, but because I’m unable to ask her any questions she hasn’t already answered many times. That she is considering leaving the coalition because the state government is not putting enough pressure on the army and on the national government in Delhi is at least worth a mention in the local press, as I will later discover. It is striking, says Mehbooba Mufti, alluding to the ‘faked encounters’, that a terrorist attack always occurs exactly when calls to withdraw the soldiers get louder.

She takes me along the next day on a tour through the villages of her constituency in her Ambassador – the Indian saloon car we know from Agatha Christie films – and with an escort of fourteen military vehicles. Although she said yesterday that the Kashmiri police were easily able to ensure domestic security, today she admits that the Indian soldiers guarding her are necessary. The route, and especially the spontaneous detours and pauses she commands, are a nightmare for her bodyguards, whose faces show their frustration and tension. Is it a show she’s putting on for the foreign reporter? She wins elections by financing a well here and a cemetery fence there, listening to the complaints about an arrested son, listening to the mistreated father, writing down names, promising to look into it. It occurs to me that, if all the members of the Establishment did their campaigning on the rural tracks, the country would at least have more wells and fewer torturers. The people along the roads and tracks welcome the official car.

‘What has the whole uprising got us?’ Mehbooba Mufti asks, showing signs of agitation: ‘That we would be happy today to have the autonomy back that we had before the uprising.’

Kashmir teaches not only how far democracies can go. Perhaps more frighteningly, it also teaches what they can get away with once they declare a state of emergency. One soldier for every ten inhabitants and extreme harshness – that’s enough to break the backbone of even the most rebellious population. When I get out halfway back to Srinagar to return with my own driver, Mehbooba Mufti points me the way to a nearby shrine, the tomb of a mystic.

‘Shall I pray there for you?’ I ask.

‘No, pray for Kashmir.’

NIGHT

Because the city seems so normal by the light of day, it takes a few days before I understand why no one wants to meet with me in the evening. If you have a car, you can drive through the empty, unlighted streets to the house of an acquaintance or to one of the more elegant restaurants, which are open until nine or, at the latest, nine-thirty. Later than that, you could probably find a bar, if you are rich enough to afford the expensive drinks. But there are no taxis to be had after eight and not even a rickshaw after nine. Even my own driver, Faroq, who cherishes me like his own personal state visit, can’t be persuaded to go out that late, not for double the fare. The only way I could move him would be to ask it as a favour, but then he wouldn’t take money at all. Once, Faroq drops me off in the city at seven because I have arranged to visit someone. They’ll bring me back to the houseboat, I reassure him. To deter my hosts from driving me home themselves, I tell them my driver is waiting outside. You always find a rickshaw or something, I say to myself. As I walk through the city for the next two hours, it feels as sinister as a minefield. There’s not even a soldier to be seen, even at the checkpoints. At this hour only ghosts are abroad in the city, says the ferryman, who has waited nervously at the dock to take me across to the houseboat. Besides my jacket and sweater, I warm myself with the sweet jasmine tea that the boat owner brings in a thermos bottle, as every night, before bedtime.

HOUSEBOAT 3

Another Indian family arrived yesterday evening, of about the same composition as the engineer’s family from Calcutta, to judge by the noise that kept me awake late: a man; some women; tired, crying children, or perhaps only one child. The man, who has just come on deck, spoke to me before in Hindi and was perplexed that I was not one of the staff. I can’t tell whether he doesn’t speak English or prefers not to talk to me. The engineer’s wife, on the other hand, gives me a greeting. In general, middle-class Indian women do not seem to be in the habit of answering the greetings of male neighbours on the first day. Perhaps out of pity, she nodded to me for the first time when I sat alone at dinner before the tomato chicken – being alone seems to be something only holy men can be expected to bear – she even smiled, and this morning so did her older daughter, who is taller than I am and plump, and looks seventeen, which doesn’t make life easier for a thirteen-year-old. When they come back to the boat, she turns on the television set before going to her room – usually quiz shows. Yesterday evening, as I sat freezing in my idyll on the Dal canal, I followed with one eye a TV series about a youth striving after a beautiful girl – in vain so far, but the next instalment is on today.

THE SHRINE

An excursion to Sokkur in western Kashmir, where Ahad Baba, one of Kashmir’s highly revered mad holy men, whom I wanted to visit, has just left for Srinagar. He had an inspiration to go, they explain to me with a shrug, as if Ahad Baba might be inspired tomorrow to fly to New York. Faroq, my driver, offers to take me to the shrine of the medieval mystic Baba Shakur-ud-Din, so that the two hours we have driven will not be for nothing. If the Islamists have not prevailed, it is not only because of the superiority and brutality of the Indian army. It is also because most Kashmiris are dedicated to their traditional faith with its mystical influences. In contrast to Afghanistan, Iran and parts of Pakistan, Sufism in Kashmir has held its ground against the new ideology.

The shrine is on an isolated mountain, an outlier of the Himalayas jutting into Wular Lake, the highest lake in southern Asia. On the mountaintop, everything that makes up Kashmir’s culture and attraction comes together in a powerful experience of nature and religion – the giant expanse of water below the shrine like a blue-green oil painting; the fecund meadows and forests in the valley, the glaciers round about; emanating from the shrine the song of an enchantingly mournful choir.

Following other visitors, I first enter a little mosque to one side of the actual sanctuary. When I come back out after prayers, the choir has stopped singing. I enter the shrine and am amazed to find no group inside it that I could have heard singing just now. Just one young man is reciting something from a divan or a prayer book in a soft singsong voice. The unornamented hall also contains mostly young people, the boys with stylish haircuts, the girls in colourful saris, their scarves pulled up over their heads, each one praying singly, including children, a few old men and women in various positions, some standing, some sitting, some crouching, two in ritual prayer. Other voices are lifted and mix in with the singsong in all corners of the room. And suddenly the choir is there again.

HOUSEBOAT 4

The cordial warmth of all the Kashmiris I come in contact with, which is staggering even by Eastern standards, contrasts with the forbidding or at least sceptical looks I encounter in the street. Do the people take me for an Indian? Gazes do not grow more inviting in the mosque, perhaps because renegades are dreaded most of all. Kashmiris, the boat owner said this morning as he brought the jasmine tea, Kashmiris recognize each other wherever they meet, whether Hindus or Muslims, and when they meet far from home they weep in each other’s arms.

Intimidated by the threats, arson and several hundred murders committed by Islamic extremists who gradually hijacked the originally national resistance, almost all the pandits, as the Kashmiri Hindus call themselves, have left the Kashmir Valley, about 600,000 people. The engineer from Calcutta thinks the pandits were driven to flee not by isolated fanatic groups but by the masses. The boat owner, on the other hand, asserts that the Indian army expressly permitted some terrorists to terrify the pandits so that people would think the Muslims were barbarians. The engineer would not deny what the boat owner says next: ‘In the 1980s we not only lost hundreds of thousands of lives, not only ruined our economy and brought up a generation that knows nothing but war: we also lost our reputation, our dignity. The world thinks we are Taliban.’

‘No, it’s not as bad as all that,’ I say, but I don’t mention the reason: that the world doesn’t think of Kashmir at all, or vaguely remembers at most the decapitation of a Western tourist.

‘Then we rank just below the Taliban,’ the boat owner says.

When the attacks were going on, he often slept at his Hindu friends’ houses to protect them, and he wasn’t the only one. Now he urges them on the telephone to come back. The pandits were generally better educated, says the boat owner; the Kashmiris need them, especially in the schools, where there is now a shortage of teachers. The engineer finds that the Kashmiris’ urging is limited and points out that no Muslim leader has yet apologized publicly for the expulsion.

‘That’s true,’ the boat owner replies to the objection when I raise it with him, ‘but with 600,000 Indian soldiers who have broken every bone in our bodies it is perhaps too much to ask for us publicly to apologize and demonstrate for the pandits’ return.’

The engineer, each time I mention the army’s brutality, does not dispute it outright but refers to the expulsion of the pandits. At the same time, he affirms that there is really no hatred between Hindus and Muslims, between Indians and Kashmiris, and asks how it is in the Middle East. I answer that an Israeli cannot simply take a stroll through Hebron, nor a Palestinian through an Israeli settlement. And in Germany? Naturally the engineer knows the reports of foreigners being beaten up, including Indians. In Germany too there are places, I say, that a person with dark skin would do well to avoid. That is unimaginable in Kashmir, says the engineer in amazement. In Kashmir, any Indian can go wherever he wants without having the least difficulty or fearing for his safety. He himself has never experienced a friendlier reception anywhere.

The boat owner lends me the nineteenth-century account of an English traveller who describes the exploitation of the Muslims by the pandits and calls on the British colonial government to intervene: ‘Everywhere the people are in the most abject condition.’ It can’t have been just a few militant groups who interpreted the Asian tradition of ‘we are all brothers’ as if it referred to Cain and Abel.

IN THE COUNTRYSIDE

In the air of the Martand Surya Temple there is peace, real peace: Sikhs playing cricket by the temple wall, old Muslims stretching out on the lawn, a few older pandits who offer me a chair. Neither the Indian government nor the state government in Kashmir does anything to bring back the expatriates, or even to compensate them, they complain, and, as per Asian custom, they will not hear a word against their Muslim neighbours. Of the two killed here in the village, one was a Muslim himself, say the pandits: the guardian of the temple, whom the outside militants took for a Hindu. I see two women playing with their hands in the big basin, the younger one a heavenly beauty of the kind told of in fairy tales: in love at first glance; her or death. I ask the two whether they live here – Yes – and how life is for them now – Good. Their answer sounds honest, and so I am glad that there are younger pandits in Kashmir too, until it transpires that the women are Muslims. The heavenly beauty pulls up her scarf over her head for the photo, as if she knew every trick from every fairy tale under the sun.

Out of five hundred Hindu families who once lived here, thirteen remain, and, of them, almost none but the old people are left. All around the temple are burnt-out houses, abandoned houses; on a riverbank are vendors’ stands catering for visitors. The colours of the sweets, the colours of the autumn woods, the colours of the fields and meadows, the colours of the saris – you don’t need to think about what colours you can see. You have to look long to figure out what colour the women avoid: only grey. Apart from that they wear every primary and every mixed colour in every combination imaginable, and occasionally black or white besides, and for all the variety the outfits are always harmonious, as if automatically.

I drive on eastwards, through villages with narrow lanes and stone houses that look more like Switzerland than southern Asia. The extreme poverty, ubiquitous in the rest of India, seems to be non-existent in Kashmir. The families own land. Because of its autonomy, Kashmir is the only state in India that was able to carry out a land reform after independence. Add to that the money India and Pakistan have pumped into Kashmir during the war to shore up or to buy off the leaders of the resistance. The new mansions are occupied by the old warlords.

In Mehbooba Mufti’s electoral district, through which I rode the day before yesterday in her official car, I meet the people who would never wave to it: a talk with the manager of a bank’s branch office, who inveighs against the Indians guarding his bank and longs for the Islamic caliphate; beside him his veilless employee, rolling her eyes. The struggle is not over by any means; it’s just not armed now – but it won’t be won at ballot boxes provided by the Indians, either. But in the end the bank manager would be content with the same thing as the English professor, the communist Tarigami, the resistance groups and almost every political party, not just in Kashmir, but in Pakistan and India too: autonomy and open borders. That is something I have observed on many journeys: conflicts that seem hopelessly complicated, like that between Israel and Palestine or that in Afghanistan, are the exception. Most conflicts, such as those in Aceh, in Chechnya and here in Kashmir, would be solvable; a willingness to compromise has long since been attained – only someone has to take the trouble to put pressure on the actors, as actually happened in Aceh after the tsunami, when peace negotiations were not only begun, but brought to a conclusion within months.

Samir and Riaz, both educated, in their mid-thirties and fathers, one a computer programmer, the other a white-collar worker, show me their town in which no house is without a burst of bullet holes in its façade. The epicentre of the uprising was in this area. We sit down on the grass on the edge of a football pitch. Samir used to play for Kashmir in the under-nineteen team. All the things the army did – searches, rapes, always the same stories; everyone here has a sister, a father, a son who fell into their hands. Samir shows me his scars. But it’s true, the Indians are trying to regain trust now, even the army itself. The government has started a few development programmes, opened social welfare facilities, invested a little money in the schools. ‘But when a person has lost three sons to the army’s bullets, he will not trust the Indians again,’ Samir says.