Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Saqi Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

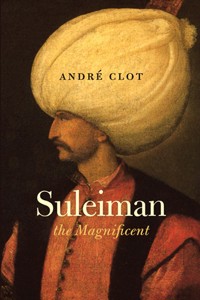

Suleiman the Magnificent, most glorious of the Ottoman sultans, kept Europe atremble for nearly half a century. In a few years he led his army as far as the gates of Vienna, made himself master of the Mediterranean and established his court in Baghdad. Faced with this redoubtable champion, who regarded it as his duty to extend the boundaries of Islam farther and farther, the Christian world struggled to unite against him. 'The Shadow of God on Earth', but also an expert politician and all-powerful despot, Suleiman ruled the state firmly with the help of his viziers. He extended the borders of the empire beyond what any of the Ottoman sultans had achieved, yet it is primarily as a lawgiver that he is remembered in Turkish history. His empire held dominion over three continents populated by more than thirty million inhabitants, among whom nearly all of the races and religions of mankind were represented. Prospering under a well-directed, authoritarian economy, Suleiman's reign marked the apogee of Ottoman power. City and country alike experienced unprecedented economic and demographic growth. Istanbul was the largest city in the world, enjoying a remarkable renaissance of arts and letters; a mighty capital, it was the seat of the Seraglio and dark intrigue.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 808

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Suleiman the Magnificent

André Clot

Suleiman

the Magnificent

Translated from the French by

Matthew J. Reisz

SAQI

In memory of my father and mother

eISBN 978-0-86356-803-9

First published as Soliman le magnifique by Librairie Arthème Fayard, 1989 © Librairie Arthème Fayard Translation © Matthew J. Reisz

First English edition published 2005 by Saqi Books This eBook edition published 2012

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A full CIP record for this book is available from the British Library. A full CIP record for this book is available from the Library of Congress.

Printed and bound by CPI Mackays, Chatham, ME5 8TD

SAQI

26 Westbourne Grove, London W2 5RH

www.saqibooks.com

Contents

Preface

A Note on Pronunciation

At the Dawn of the Golden Century

Part One: The Sultan of Sultans

1. The Padishah’s First Triumphs

2. The Magnificent Sultan in His Splendour

3. From the Danube to the Euphrates

4. The Struggle with Christian Europe

5. Francis I and Suleiman

6. The Tragic Period

7. The Twilight of the Empire

Part Two: The Empire of Empires

8. The Orient at the Time of Suleiman

9. The Greatest City of East and West

10. A Dirigiste and Authoritarian Economy

11. Town and Country

12. The Age of the Magnificent Sultan

Three Centuries of Decline and Fall

Notes

Appendices

1. The Pre-Ottoman Turks

2. Turkish Civilization before the Ottomans

3. The Janissaries

4. The Law of Fratricide

5. The Timar System

6. The Divan

7. The Dervish Orders

8. The Ottoman Fleet

9. The Army on Campaign

10. A Grand Vizier’s Career: Sokullu

11. Henry II and Suleiman

12. Suleiman’s Death

13. The Turkish Baths

14. The Mendes Family

15. The Capitulations

16. Islam and Painting

Genealogy of the Sultans of the House of Osman

Chronology, 1481–1598

Glossary

Bibliography

Index

Maps

I. The Ottoman Empire in 1566

II. Istanbul at the Time of Suleiman

III. Caravan Routes

Preface

The main object of this book is to bring back to life a man, an empire and an era relatively close to us in time and yet little known. Indeed, for many people, they seem at least as alien as the states and sovereigns of antiquity and the Middle Ages. I would have liked to provide a fuller understanding of the most powerful of Ottoman sultans, and especially of the men, institutions, economy and individual countries which made up his great empire, but for various reasons I decided to restrict myself to broad-brush descriptions. I hope, however, that educated readers will be encouraged to go deeper into the study of Turkish history and civilization. They certainly deserve such attention. (Turkish studies in France have produced a whole catalogue of remarkable works to which, as the Bibliography testifies, I have often turned for inspiration.)

I should like to express my gratitude to the people who have helped me carry out the work for this book. In first place comes Professor Louis Bazin, Director of the Institute of Turkish Studies at the University of Paris III, who encouraged me to take on the project, opened many doors and then was kind enough to read the finished product and provide many learned comments. Jean-Louis Bacqué-Grammont, head of research at the Centre National de Recherche Scientifique (CNRS) and an eminent specialist on Iranian and Ottoman history, provided me with many documents and books and also took the trouble to look over the text and suggest many amendments. Abidin and Güzin Dino gave advice which clarified a wide variety of issues and obtained some very useful texts and translations for me.

I must also express my thanks to Fernand Braudel, who gave me the opportunity to use documents at the Simancas Archives, and to Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie for valuable guidance about the problem of climate in the sixteenth century.

A Note on Pronunciation

For Turkish names, a simplified form of spelling has been adopted which will pose no problems for the English-speaking reader. The only exceptions are the following:

c pronounced j as in jam

ç pronounced ch as in church

ǧ not pronounced; lengthens the preceding vowel

ş pronounced sh as in shall

(Words that have an accepted English form, such as pasha, have retained this spelling.)

At the Dawn of the Golden Century

I who am the Sultan of Sultans, Sovereign of Sovereigns, Distributor of Crowns to Monarchs over the whole Surface of the Globe, God’s Shadow on Earth, Sultan and Padishah of the White Sea and the Black Sea, of Rumelia and Anatolia, of Karaman and the countries of Rum, Zulcadir, Diyarbekir, Kurdistan, Azerbaijan, Persia, Damascus, Aleppo, Cairo, Mecca, Medina, Jerusalem and all Arabia, Yemen and many other lands that my noble forebears and illustrious ancestors . . . conquered by the force of their arms and that my August Majesty has also conquered with my blazing sword and victorious sabre . . .

Letter from Suleiman to Francis I of France

1453: Mehmed II enters Constantinople. 1492: Columbus discovers America and the Catholic Kings capture Grenada from the Moors. 1519: Charles V is elected Emperor of Germany. 1520: Luther is condemned for heresy.

Whatever dates and events we choose to mark the start of modern times in the West, one crucial fact stands out: after an extended crisis which struck Europe in the 14th and 15th centuries and shook medieval civilization to its foundations, the feudal age was utterly dead. The age of states was born amid economic and social change unprecedented since the end of the Roman Empire. It represented almost a new civilization, a veritable renaissance or rebirth.

The crisis of the two previous centuries, the most serious the West had known for a millennium, affected most of the Old World. In the wake of disaster all over Europe brought by wars and peasant revolts, the Black Death arrived from the Black Sea port of Caffa and spread its own share of suffering, misery and insecurity. The Christian nations presented a sad spectacle: conflict between France and England, and between the King of France and Dukes of Burgundy; the Hussite wars and the collapse of imperial authority in Bohemia; chaos and guerrilla warfare in Central Europe and the Scandinavian countries; decadence and anarchy in Italy and Spain; an unprecedented schism within the Church. Yet this was not all. A new danger was soon to appear on the horizon in Central Europe – the Ottomans.

If the Old World had continued in its conflicts and errors, nothing could have prevented the people always described as ‘barbarians’ (although the term had long ceased to be appropriate) from overrunning the West. History is littered with the bodies of once rich and powerful states which have collapsed under the weight of their internal quarrels, offering an easy prey to conquerors or bold adventurers.

Yet this time, at the moment when all seemed lost, Europe recovered. The Battle of Castillon (1453) put an end to the Hundred Years’ War. The huge epidemics which had caused such damage in the previous century died down. Prosperity and security returned. The return to peace was accompanied by a recovery similar to that of the 12th and 13th centuries. Populations began to increase (numbers doubled in France between 1450 and 1560), deserted villages were repopulated and towns expanded. Agriculture increased its yields as new, mainly industrial forms of cultivation were introduced. More and more land was given over to wine-growing and animal husbandry.

Industrial processes improved existing products or created new ones in metalwork, glassware, light drapery, silk and linen. Iron, silver and copper mining, spurred on by the demands of industry, took off. Mines abandoned since Roman times were brought back into operation. (The Habsburg fortunes were based on the mines they operated or used as security for loans.) Printing and hence also paper making took off. With the return of peace, trade in products of every kind started to flow again on the traditional trade routes: within Europe, and from the Orient by way of Venice or Eastern Europe to Poland, Western Europe and the Baltic states. Yet now there was also increasing trade from the Atlantic ports to Central Europe and the North. Fairs held on set dates and large banking organizations eased the flow of capital. The monetary economy expanded, along with resort to credit facilities.

This renewal in every aspect of Western life, reflected in art and literature, spurred on the ambitions of the sailors who set off to explore the world. Europeans were soon to discover other civilizations, which in turn learned of the existence of countries such as France, Spain and Italy, located on the edges of the huge continent which separated the two great oceans. The Grand Siècle – the Great (16th) Century – was essentially a century of encounters.

Yet it was also a century of great heads of state, of kings and emperors who left an indelible mark on it. The sovereigns of the 14th and 15th centuries struggled first to ensure the survival of their states, and then to secure their own positions by weakening the great feudal lords. In France, England, Italy and Portugal, kings and princes at the end of the 15th century brought under control the dukes and barons who encroached on their power. The great landowning dynasties like the Bourbons in France would be around for a long time, yet their battle was hopeless: the ancient notion of sovereignty inherited from Roman law and revived by Philippe le Bel’s jurists was destined to prevail.

Things were very different in Central and Eastern Europe, where the nobility not only prevented the emergence of modern states but greatly contributed by their disorderliness to the success of the Turkish forces and the loss of national independence. Everywhere else, even in the papal states, sovereigns used similar means to maintain their powers within and outside their territories; few serious challenges were forthcoming.

States of every kind require an armed force capable of ensuring their neighbours will respect their wishes. Feudal armies were no longer suited to the great states which were coming into being. The techniques of war, which had developed rapidly since the invention of artillery, now required experts. A French decree of 1439 laid down that the army belonged to the king and that no others were permitted. In 1445 the king was granted 20 permanent cavalry regiments. Three years later, the infantry was organized into irregular companies of bowmen which were replaced by 7 legions of 6,000 men under Francis I. The French artillery was soon to become one of the best in Europe. Like the rulers of the Italian republics, the king also recruited mercenaries.

Spain established a form of regular military service with a new unit known as a coronelia, made up of 12 companies of pikemen, harquebusiers and cavalry. Together they formed the tercio, a formidable force. Armies became and remained permanent, although an increasing drain on resources.

Throughout the Middle Ages, kings lived by coining money, on their feudal and seigneurial rights, and on revenues from landed estates. The development of armies, international politics and royal ambitions made such means insufficient. Throughout Europe, sovereigns adopted the same solution: permanent and regular taxes levied on their subjects. The Estates General in France were called upon less and less to vote in taxes and, from the time of Charles VII, governments levied the taille and aides directly. Francis I reorganized his finances by creating a treasury to centralize all state revenue.

In England, by contrast, where the king failed to make the taillage permanent, Henry VII fell back on forced loans from the nobility. Henry VIII confiscated clerical property – the reform of the Church was a way of getting rich. In Spain the possessions of Jewish and Muslim ‘Infidels’ were confiscated. Before gold started to pour in from the New World, money also came from the sale of indulgences, thanks to a ‘crusading papal bull’, and the income of the great chivalric orders. Everywhere in Europe, money lenders – whom we would call bankers – advanced money to sovereigns.

Another general development in Europe as kings and princes reinforced their powers over their subjects was the creation of a new system of administration based on functionaries. Although they almost always came from a humble background, recruited among the clergy or lesser nobility, they propped up the ambitions of sovereigns and reinforced their prerogatives. In Spain, France and, with the Star Chamber, in England, the powers of the king’s councils increased while representative institutions were progressively enfeebled. With the exception of Venice, the Italian states were either true monarchies such as Naples or closer to monarchies than republics (Milan, Florence). Everywhere absolutism was triumphant, as an inexorable result of the need to concentrate power in a Europe dominated by international politics and economics – and where great ambitions were soon to come face to face.

Whether it is just a historical accident or a reflection of an age of strength and renewal, states almost all over Europe, the Orient and even India were ruled by powerful personalities for over a hundred years. Such men were warrior chiefs, diplomats, administrators, often artists yet always ambitious – and rarely weighed down by scruples. None ever reproached his rivals with their terrible crimes – massacre, disembowelment, kidnap, plunder, oaths betrayed as soon as made – since he knew he had committed just as many. None ever confused religion – to which they ostentatiously proclaimed their adherence – with morality. The 16th century was an age of iron.

1509: Henry VIII comes to the throne of England. 1515: Francis I becomes King of France. 1516: the accession of Charles V in Spain. Four years later, Suleiman puts on the sword of Osman. These four men dominated Europe and much of the inhabited earth for nearly half a century, united in their desire to increase their power by any means, and particularly by war. All four were warrior princes yet claimed to be fervent lovers of peace – when it served their interests.

The oldest, Henry VIII, was no cardboard cut-out king. ‘A potentate to his fingertips’, according to one biographer (who compared him to Rockefeller), Henry was interested only in power. He went as far as establishing his own religion – not even God would stand in his way. Of his six wives, two were handed over to the executioner, two more cast aside. Yet this cultivated Blue Beard, artist, Erasmus-like humanist and archetypal Renaissance prince made of England a rich and powerful country which at one point held the balance of power in Europe. Both Francis I and Charles V tried in turn to gain Henry’s favour, yet for a long time he skilfully and opportunistically managed to manoeuvre between them. How different from the early years of Henry VII’s reign, when a penniless country was surrounded by plotters! Half a century later, Elizabethan England sparkled with health and riches.

Facing the English ogre across a Channel which has often seemed wider than an ocean was the dazzling Francis I of France, ‘as handsome a prince as any in the world’, the knightly king, gallant and charming, with his own special touch of gaiety and joy. The beau seizième siècle is essentially his. The Renaissance was bursting forth in every field: artists, scholars, great writers who celebrated human dignity and at last gave man his rightfully pre-eminent place. Castles sprouted on the banks of the Loire and the king, open to every innovation, summoned painters and sculptors to his court and founded the Collège de France. Yet Francis was also a man of great political vision and bold ambitions. ‘He had’, according to Lavisse, ‘an exact sense of the kingdom’s interests; in the struggle with Charles V, he revealed his energy and skill on more than one occasion; he knew how to win allies; he dared appeal for help to the Turks when he needed to defend French independence or grandeur. In all these ways, he expressed his freedom of mind and clarity of vision . . . In a quarter century full of dangerous external developments, our country carried through crucial social, economic, intellectual and moral changes which helped set her course for the future.’

The third great figure in a Europe opening up to the outside world was Charles V of Spain – often known as Charles Quintus – Francis’s rival and adversary. Henry and Francis were both generous-spirited live wires and enthusiastic womanizers. Charles was sullen, slow and reticent, with a hanging jaw. Little inclined to study in his youth, he was addicted only to the most ignoble of vices: gluttony. Yet this unappealing exterior hid a lively imagination, an unyielding doggedness, a wise and scheming mind and a constitution equal to every trial. The somewhat melancholy young man was to become one of the keenest participants in the European struggle for power. Of boundless ambition, he wanted to become emperor, bought outright the votes of the seven electors – and triumphed. As a result, the 150 million gold francs he borrowed from the Fugger banking dynasty had an incalculable long-term impact on the continent, although the empire itself – ‘a construction too great for the strength of a single man’ – did not survive his death.

Yet would the century present such a lively and colourful scene – so full of intricate diplomacy, sword thrusts, stories of adventure and openings to new countries and new ideas – if it were not for great sovereigns like Ivan III (‘Ivan the Terrible’), who brought all the Russian lands under his sway, like the Sophy,1 Shah Ismail, or like Babur and Akbar in India? For the countries to the East of Europe, the 16th century also signified increasing contact with the outside world, the creation of unified states, new intellectual horizons. It was then that Russia was born of fire and the sword – although also with the help of Greeks and Italians called up by Ivan III. It was then that Shah Ismail, grandson of an Emperor Comnenus from Trabzon, a boy of dazzling beauty with something ‘grand and majestic’ in his eyes yet also of appalling cruelty, recreated Iran as a political unit all the way from Bactria to Fars. An exquisite civilization emerged from the fusion of Shiite Islam2 and the earlier artistic and intellectual traditions of Iran, together with influences from China and Italy. Its refinement and elegance achieved supreme expression under Shah Abbas. Later, when Babur seized Delhi in 1526, he was to graft it onto the trunk of existing Indian art to create the Moghul renaissance. It reached its apogee before the end of the century under his grandson Akbar.

An Iron Race

These kings and emperors, or at least the European ones, were successors to generations of sovereigns who had long fought to retain or, more often, extend their territories. The Middle Eastern rulers, comparative latecomers, who were destined like Suleiman to achieve unparalleled power and glory, made a sudden appearance on the scene when they crushed and conquered parts of the Eastern Roman Empire. We can hardly imagine today the shock of the Turks arriving at the gates of Europe, or the fear they continued to inspire into the 18th century and beyond, among a populace which saw them as barbarians with knives between their teeth.

For almost ten centuries, the Turks, ‘one of the iron races of the ancient world’,3 had waged war on the steppes of Upper Asia. Having set out from the Altay mountains and the Orkhon and Selenge basins, the first Turks history has been able to identify – the Tabghach (To-Pa in Chinese) – occupied Northern China in the 5th century and then blended into the native population. A hundred years later, other Turks conquered first Mongolia and then Turkestan. Masters of an immense empire extending from Korea to Iran, they used the Sogdian alphabet, a predecessor of the runic script.4 This empire disappeared when its founder, Bumin, died in 552. It then split in two: Bumin’s son Muhan ruled over the Eastern Frontier Region, to the East of the Tien Shan in Mongolia; to the West, on the steppes of Siberia and Transoxania, the emperor’s second-born son, Istami, became khan of the Western Frontier Region.

The inscriptions at Orkhon, carved around 730, preserve for us in powerful poetic language the memory of that great adventure: ‘O Turkish chiefs! O Oguz! O people, listen! As long as the sky has not fallen and the earth has not split open, who will be able to destroy the institutions of your country, O Turkish people? . . . I did not become the sovereign of a rich people but of a hungry, naked and wretched people. We agreed, my younger brother, the Prince Koltegin, and I, not to allow the glory and renown our father and uncle won for our people to perish. For love of the Turkish people, I have neither slept at night nor rested by day . . . and now my brother Koltegin is dead. My soul is filled with anguish, my eyes can no longer see, my mind no longer think. My soul is in torment . . . My ancestors subjugated and pacified many peoples in every corner of the world, making them bow their heads and bend their knees before them. From the mountains of Khinghan to the Gates of Iron, the power of the Blue Turks extended . . .’5 This empire, in its turn, collapsed in 740.

Meanwhile the first group of people, the Western Toukiues, were replaced for a century by the Uighurs. The Uighur Empire borrowed from outer Iran (the Iran of the oases of Turfan and Beshbalik) its artforms and Manichaean religion and became more and more civilized. Then it was overcome by the Kirghiz and disappeared, only to be reborn as a Buddhist state in Chinese Turkestan. To the West, the Turkish tribes converted to Islam. It is from this world, ceaselessly warring and ceaselessly changing, that the Ghaznavids, the Ghourids and the Seljuks6 would soon emerge.

The ‘iron race’ had set out long ago from the depths of Asia, and wandered from the Caspian to the Pacific, crossed deserts and valleys, founded empires, taken up and abandoned religions. Now, on the harsh steppes of Anatolia, they found a country with a climate much like that of Central Asia and put an end to their wanderings. The Seljuk Empire was formed, with its great chiefs (Alp Arslan, Melikshah) and great administrators (Nizam al-Mulk), and then shattered into rival principalities. It was then, at the start of the 13th century, that the Osmanli or Ottomans appeared.

According to legend, Suleimanshah, the chief of the tribe from which the line of Osman descends, fled before the Mongol invasion of Khorasan in Eastern Anatolia, but then, when the wave of invaders led by Genghis Khan ran out of steam, decided to return to Iran. He was drowned in the Euphrates on the way back. Two of his sons, Dundar and Ertugrul, considered this a bad omen and turned East, towards the part of Central Anatolia inhabited by the Seljuk Turks. They are said to have arrived unexpectedly at the scene of a battle between combatants they did not recognize. Ertugrul decided to intervene on the side which seemed to be losing. This was Alaeddin, sultan of Konya, who was engaged in a desperate struggle with the Mongols. When he won an unexpected victory, he offered Ertugrul a fiefdom in the region of Sogut (between Bursa and Eskişehir) as a reward. Thus the Ottoman era began.

This legend is rather too good to be true. Put together much later, in the 15th century, it was inspired by popular stories about the life of the Seljuk prince Suleiman Kutlumuş, his son Kiliç Arslan and the flight from the Mongols of Celaleddin Rumi, the founder of the Mevlevi order. The most reliable sources lead one to believe that the small group of men who gave their name to one of the most powerful empires in human history were descendants of gazi (Muslim fighters who formed numerous communities on the borders of Islam to ward off the Infidels, just as the akritai7 protected the Byzantine Empire). The struggle against the Christians was always critical for the Ottomans – the day it was abandoned marked the start of the empire’s decline.

These gazi – ‘instruments of the religion of Allah, the sword of God’ – were established in the Islamic parts of the Orient and, from the 9th century, in Khorasan and Transoxania. Turks were always dominant in the gazi, which attracted unemployed wanderers, heretics fleeing persecution and even Christians in search of loot. They sacked Sebaste (Sivas) and Iconium (Konya). Later, Turks who had remained outside the Seljuk Empire often joined gazi. The Mongol invasion, which made the Seljuks vassals of the Il-Khanid Empire (founded by Hulegu, grandson of Genghis Khan), increased the westward migration of the Turkish tribes. In search of territory, they too joined gazi and attacked the Byzantines.

It was then that an event with incalculable consequences occurred: the eastern defences of Byzantium collapsed. The Latin-speakers of the Fourth Crusade left Constantinople (which they had held since 1204) and the Emperor Michael Palaeologus returned. The empire’s centre of gravity moved West. The akritai, who were hostile to the Palaeologus dynasty, made no attempt to hold the frontiers.

The gazi leaped into the breach and each tried to carve out from the spoils of the Byzantine Empire a territory as large as its armed forces could control. Anatolia split into several principalities based on gazi. The chiefs who had led them to victory founded dynasties. Some collapsed almost at once, but many survived far longer. Their links with the Seljuks of Konya (who had nominally taken over from the great Seljuk dynasty of Iran) were very loose; they were not in any real sense vassal states. The beys of Aydin, Karaman and Menteş, with territory bordering the Aegean, gained immense wealth from piracy. The Osmanli bey, on the other hand, possessed none of their advantages: his territory was situated in the North-West of Anatolia on the borders of the Turco-Byzantine area, far from the sea and fruitful sources of pillage. But Osman and his successors lacked neither skill nor audacity in seizing every favourable opportunity.

Osman revealed his genius as a politician by immediately laying the foundations of a state, largely inspired by the example of the Seljuks, with their traditions, guilds and culture inherited from the older Muslim world and the Iranian-Sassanid Orient. He seized Nicaea in 1301, after defeating the army sent against him by the Emperor of Byzantium. As his fame increased, he attracted to himself not only brigands and deserters but intellectuals, artists and the cultivated elite of the towns. Theologians and jurists (the ulema) provided the basis for the administration and brought with them a spirit of tolerance characteristic of Muslim dealings with Jewish and Christian Infidels. Schools of theology modelled on the Seljuk medrese soon opened in Iznik (Nicaea) and Bursa (Brusa). By the end of the 14th century, while other principalities were still wasting their energies on costly rivalries, the Ottoman Turkish state was born. Soon it proved its superiority in the whole of Anatolia, and then on the other side of the Propontis, in Europe.

It was the Byzantines themselves who provided the opportunity, when John VI Cantacuzenus asked for the help of Osman’s son Orhan in his struggle against John V Palaeologus and even offered him his daughter Theodora in marriage.8 A few years later, in 1354, Orhan captured the fortress of Gallipoli, on the European shore, when an earthquake had caused it to collapse. Since he already controlled positions on the Asian side, he was now able to cut off Constantinople from its European possessions whenever he wished.

The Christian world was alarmed. There was talk of a new crusade – not to save Jerusalem, but to deliver the capital of Byzantium from the Turkish menace. Even a reunion of the Roman and Orthodox Churches was discussed . . . But it was too late. The Balkans and Europe itself were in total disorder. The Serbian, Byzantine and Bulgar Empires fought among themselves. The rivalry between Genoa and Venice in the Eastern Mediterraean was fiercer than ever. The Byzantine Empire, its forces quite spent, was open to capture.

Fate – known in the Orient as ‘the will of Allah’ – decided that a bold and cunning sultan, Murad I, should be ruler of the Ottomans at the crucial moment. Having succeeded Orhan in 1362, it was he who set in motion the occupation of the Balkans. In a matter of years he led his troops from Marmara to the shores of the Adriatic. With Bulgaria conquered and Hungary under threat, Europe was frightened. Every month the Turkish ‘hordes’ increased in size. Attracted by adventure and the chance of loot, many men, most of them Greeks, joined the sultan’s service. Local populations, long oppressed by Serbian and Bulgarian feudal lords and by religious orders, put up little resistance to the Turkish occupation. The Catholic Church was suppressed, to the delight of Orthodox Christians. Many soldiers who had fought in the ranks of the Serbian and Bulgarian armies joined the Ottoman side when offered grants of land and exemption from taxes. Nobles allowed to retain their fiefdoms agreed to serve in the Turkish cavalry.

After the capture of, first, Gallipoli and then Demotika and Edirne (Adrianople) in 1362, the Christian powers made a vain attempt to react. Urban V’s appeal for a new crusade fell on deaf ears, since neither France nor England, caught up in the Hundred Years’ War, responded. Only Count Amédée of Savoy set out and recaptured Gallipoli, but, alone against Murad, he was soon forced to beat a retreat and return to Italy. Murad won victory after victory and, on 15 June 1389, crushed the Serbian army of Prince Lazar at Kossovo (the Field of the Blackbirds). Murad himself was assassinated; Lazar, taken prisoner, was executed. The Turks occupied the Balkans; they were to control the area for five centuries.

Murad’s successor, Bayezid Yildirim (or ‘The Thunderbolt’), continued Murad’s conquests at an even more irresistible pace. In 1393 he annexed the area of Bulgaria around the Danube, then Thessaly and Wallachia. At last, the Christian nations made a supreme effort. Sigismund, King of Hungary, called for a crusade. For once (but it was to be the last time), the response was favourable from both the English and the French. At the head of the French army were John the Fearless, Admiral Jean de Vienne, Marshal Boucicault, the Count of La Marche and Philippe d’Artois. The Grand Master of the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem took part along with the Elector Palatine. Each side brought about 100,000 men to the field. The armies met on the lower Danube near Nicopolis, which the Christian armies had besieged. Against the advice of Sigismund, who wanted to wait for a Turkish offensive, the French nobility impatiently launched an attack. They managed to break through the first two Turkish lines but were too exhausted to exploit their advantage. The Turkish cavalry and janissaries (the best corps of the day) easily surrounded the French horsemen and, after several hours when the result seemed uncertain, the Serbian contingents of the Turkish army joined battle and tipped the balance.

Bayezid soon won over the few surviving independent emirates and decided to seal the fate of Constantinople. In the event, the town was saved, for a considerable period of time, not by the Christians, but by another Turkish conqueror. This was Timur Leng (‘Timur the Lame’) from the depths of Central Asia and known to us as Tamerlane.

It was at Ankara, in the heart of Anatolia, that the armies of Bayezid and Tamerlane met in 1402. Although the emirs defeated by the Ottomans had often joined Tamerlane, their troops had sometimes joined Bayezid. As with the Serbs at Nicopolis, it was they who decided the result of the battle. When they saw the combat hanging in the balance, they were finally swayed by loyalty to their princes and thus changed sides to fight with Tamerlane. Bayezid’s army was defeated and he was taken prisoner.

The Christian powers failed to seize the chance they had been offered by fate. With the Turkish Empire crippled by defeat and the sons of Bayezid at loggerheads, reconquest of the Balkans was possible. Nobody moved. In a few years, Mehmed I Çelebi (‘the Lord’), one of Bayezid’s sons, eliminated his brothers Isa, Suleiman and Musa. He brought back order and stability to the empire. First Mehmed I and then Murad II (who succeeded him in 1421) returned to a policy of expansion. Their main aim and purpose was crystal clear: the conquest of Constantinople.

Again the Christians wanted to halt the Turkish advance. Ladislas Jagiellon, King of Hungary, and John Hunyadi, voivode (or governor) of Transylvania, gave way to the pleas of the Pope and the Emperor of Byzantium and invaded the Ottoman Empire. In 1444 they laid siege to Varna. Murad II crushed the Christian armies in a surprise attack with 40,000 men while his enemies still believed him to be 100 leagues away. Ladislas and Giulio Caesarini, the Papal Legate, were left dead on the field of battle. Emperor John VIII of Byzantium, seeing that his turn would come too, tried to win over the sultan with valuable gifts – although this naturally proved unsuccessful. His successor, Constantine Dragases, in a supreme effort to gain the support of the Latin nations, announced a union of the two churches. This only enraged the hardline members of the Orthodox Church, who made their own the formula pronounced by one of the empire’s leading dignitaries: ‘Better the Turkish turban than the tiara of the Pope ruling in Constantinople.’

At all events, it was too late. Mehmed II, who had succeeded Murad II in 1451, took pains to isolate Byzantium by making peace with John Hunyadi, with Venice, Genoa and even the Knights of Rhodes. Constantine Dragases’s appeals to the Christians fell on deaf ears. Europe left Byzantium to its fate. Now only a shadow of its former glory, Constantinople was quite unable to avoid falling into the hands of the Ottomans.

The siege began on 6 April 1453; by 29 May, it was all over. The courage of the Greeks was of no avail in the face of the Turks’ modern weapons – war machines and above all huge cannons – the six-to-one Ottoman superiority and Mehmed’s determination. The last Byzantine Emperor perished sword in hand and the garrison was massacred. In the evening, Mehmed took part in the prayers in Saint-Sophia – now turned into a mosque. The gazi warrior was on the throne of the Caesars and from there he would set forth across Europe and Asia in the pursuit of further conquest.

The Greatest Army in the World

The year 1453, therefore, marks the end of the Roman Empire. No one can fail to be amazed by the almost constant successes of the Ottoman armies, which developed in less than two centuries from a small group of fighters who waged war around their gazi in Eastern Anatolia into a force whose power reached the shores of the Bosphorus and the palace of Justinian’s successors. How can we explain that extraordinary advance which continued until the day when a counter-thrust before Vienna checked forever the Ottoman invasion of Europe?

First of all, complete anarchy had engulfed the Byzantine Empire, the Balkans and Asia Minor. If the empire had still been ruled by Justinian, Basil II or Alexis Comnenus, Turkish history would have come to an end with the Seljuks. Strong Serbian or Bulgar Empires would also have held the invaders back. But neither North nor South of the Balkan peninsula were there any such empires. Byzantium, after a period of revival under the Comnenus dynasty, had been taken and occupied by the Fourth Crusade. Although Constantinople had been recovered from the Latins in 1261, it was now hardly more than a pile of ruins. When they came to power, the Palaeologus dynasty found themselves at the head of a reduced and exhausted empire. Religious and class conflicts as well as sordid intrigues had enfeebled it. Byzantium had essentially defeated itself.

Exactly the same internal disputes and unwillingness to join forces were to be seen in the Serbian and Bulgar Empires. From time to time they woke up and found another city taken – Kossovo, Nicopolis, Varna – largely because of the frivolous life-styles of the Christian ights. The empires crumbled into the domains of rival feudal lords, where oppressed populations were happy to be ruled by anyone who would lighten their burden even slightly. ‘The serfs welcomed the Islamic armies for the same reasons that they later welcomed the French revolutionary armies.’9 The Ottomans were skilful enough to rule with justice and moderation. Even when the people did not truly support Turkish domination, the Turks’ spirit of religious tolerance soon made them accepted.10 It was this which led to the pax Ottomanica described by Toynbee.

The Ottomans were the only people to bring powerful, well trained and equipped military forces against the brave but also dissolute local knights and their undisciplined hangers-on. All contemporary witnesses declare that, for at least two centuries, the Turkish army was the most powerful in the world. The administration developed out of the army and was for a long time essentially part of it. In time of war, almost everybody became part of the army which, until the end of the reign of Suleiman, was led by the sultan himself. Many of the leading dignitaries of the state were military commanders. ‘Governing and waging war were the two main aims – internal and external – of a single institution controlled by the same group of men.’11

The discipline of the sultan’s army terrified the West. At a time when European troops were equipped and armed in haphazard fashion and often obeyed or disobeyed according to momentary whims and deserted at the first opportunity, the Turkish soldiery possessed all the qualities which make armies invincible: courage, discipline and almost fanatical loyalty. Ambassador Ghiselin de Busbecq12 often wrote about this in his Letters:

‘One or twice a day on campaign, the Turkish soldiers drink a beverage made of water mixed, when available, with a few spoonfuls of flour, a little butter, spices and a piece of bread or ration of biscuit. Some of them take with them a little bag of powdered dried beef which they use in the same way as flour. Sometimes they also eat the meat of their dead horses . . . All this will convey to you how patiently and abstemiously the Turks confront difficult times and wait for better days. How different are our soldiers, who despise ordinary food and want delicacies (like thrush and pipit) and haute cuisine even on campaign! If we don’t give them food like that, they mutiny and bring suffering on themselves; if we do give them such food, they still bring suffering on themselves. Each man is his own worst enemy and has no more deadly adversary than his own intemperance, which kills him off even if the enemy doesn’t . . . I dread to think what the future holds for us when I compare the Turkish system to ours.’

Describing the camp of a campaigning army where he spent three months, Busbecq noticed the silence reigning there, the absence of quarrels and acts of violence, and how clean it all was. No one was drunk, because the soldiers had only water to drink; their food was a sort of gruel of turnips and cucumbers seasoned with garlic, salt and vinegar. A hearty appetite was their only sauce, he added humorously.

Paolo Giovio, an Italian chronicler of the age of Suleiman, summarized his opinion of the Turkish army as follows: ‘Their discipline is far more just and strict than that of the ancient Greeks and Romans. There are three reasons for their superiority over us in battle: they immediately obey their commanders; they never worry about the possibility of losing their lives; and they can survive without bread and wine on a little barley and water.’13 It only remains to add that, at a time when provisioning was unknown in Europe, the Ottoman army’s supply lines were very well organized.

The permanent army was made up of slaves of the Porte14 (kapikulu). Two forces formed part of it: the Porte sipahi (cavalry) and the janissaries, the most illustrious corps in the Turkish army. The janissaries were formed at the start of the Osmanli era and were about 5,000 in number in the 15th century, 12,000 under Suleiman. They are sometimes given a significance they did not really possess, at least on the battlefield, since at no time did they make up the whole Turkish army or anything like it. Their role was usually to join battle after the enemy had faced attack from the cavalry and irregulars and artillery bombardment. Their fresh forces would then often tip the balance.

Their political influence, on the other hand, was immense and their demands – particularly dangerous in that they were inspired by a powerful esprit de corps – more than once forced the sultan to change his plans. No sultan could take power without granting a large accession gift agreed after long negotiations and much argument. By siding with a particular claimant to the throne, the janissaries decided the fate of the empire on several occasions. They gave much help to Murad II in his triumph over his rivals and it was thanks to them that Selim I, Suleiman’s father, defeated his brother Ahmed in 1511.

They terrified the population of Istanbul. ‘Above all, don’t let any of your people get into quarrels with the janissaries,’ the Porte functionaries advised foreign ambassadors, ‘because we would be quite unable to do anything for you or for them.’ When bands of janissaries entered a district, the shopkeepers immediately shut up shop. It was usually impossible to stop them ransacking a city after it had surrendered, as happened in Rhodes in 1521 and at Buda in 1529 despite the promises and express orders of Suleiman. During the Persian campaign of 1514, when the army was advancing with great difficulty in the region of Araxe, Selim, for all his ruthlessness, was compelled to make an about-turn. The janissaries went so far as to pierce the sultan’s tent with their lances in order to force him to go back towards the capital. Thus, if they sometimes complained when long periods of peace deprived them of booty, they also sometimes forced the sultan to cut short a war.

Their devotion knew no limits, their loyalty was absolute. Only too ready to sacrifice their lives for the sultan, in battle they formed a completely solid line of defence around him. To give expression to the link which united him with his elite troops, Suleiman enlisted in one of their companies and was paid like an ordinary soldier. His successors did exactly the same.

Compelled to be celibate and subject to strict training and iron discipline, the janissaries showed matchless strength and skill in handling their weapons. When they trooped by in silence, they deeply impressed European visitors. ‘One would have thought them friars,’ remarked Busbecq, in his account of an audience with Suleiman at Amasya. They were so still and rigid, he continued, that from a distance one could not tell if they were men or statues. A Frenchman called du Fresne-Canaye compared them with monks. Bodyguards of the sultan and his greatest asset in battle, the janissaries were fanatical Muslims – although all of them, at least in the 16th century, were of Christian origin. They were, in fact, slaves of the sultan recruited by means of the devşirme system – that is, chosen from among the provincial children who did not possess the intellectual ability to become civil servants.

This devşirme or conscripting of Christian children dated far back into the Ottoman past. When the sultan decided to collect some children in this way, a commission, including an official and a janissary, was nominated for each province (sancak). It went to each village, summoned all the boys aged between 8 and 20 and then, under the authority of a judge (kadi) and the sipahi, picked out those whose intellectual and physical abilities made them good potential soldiers or administrators. They were always from peasant families and were never only sons. Once the boys had been gathered together in the large towns, they were sent to Istanbul in groups of 100. The most promising (the içoǧlanlari) were then directed to die palaces of Galata Saray or Ibrahim Pasha, in the capital, or to those of Manisa and Edirne. The others – the Turk oǧlanlari – went to work in the fields on Anatolian farms before being enrolled in the yeniçeri or janissaries (see Appendix 3).

Under Suleiman and his successors, therefore, the system of devşirme supplied both the elite troops – the janissaries and the sipahi of the Porte – and all the administrators up to and including the Grand Vizier. All were slaves of the sultan; at a time when birth meant everything in Europe, their advancement depended solely on merit. No earlier regime, not even the Abbasid caliphs or the Mamluks, had created such a successful and large-scale slave state. From the beginning of the Ottoman Empire, slaves were educated to become officers and administrators; but it was not until the time of Mehmed II that the sultans learnt the lessons of the rebellions which had shaken the empire in the early 15th century and concluded that only slaves with indissoluble ties to their rulers could safely be entrusted with executive power. Despite the protests of well-born Turks, the system continued to develop until, at the time of its apogee under Suleiman, all the Grand Viziers without exception were Islamicized Christian slaves.

Ten Sultans Born for Conquest

The Turkish army also owed its almost uninterrupted successes to the men who commanded it: the Ottoman sultans. ‘No European dynasty produced ten sovereigns of such remarkable talents in two and a half centuries.’15 All possessed the qualities which turn men into conquerors: a talent for command, organizational ability, and the diplomatic skills shown by Osman and Orhan, the founders of the empire. Murad I, one of the dominating figures of the 14th century, was a wise and cunning warrior chief; Mehmed I rebuilt the state after the disastrous defeat at Ankara; Murad II defeated the last Christian coalition at Varna; and Mehmed II, conqueror of Constantinople, was – with Suleiman – the most powerful figure in Turkish history.

Mehmed II aimed at nothing less than world power. Considered a butcher and the Antichrist by the Christians, he was acclaimed by the Turks as their greatest leader. Under his authority, the whole world would be united. He realized the age-old Islamic dream of avenging Moawiya16 – the first Omayyad caliph, who had been forced to lift his siege of Constantinople in 677 – and wanted to go further, to outdo Caesar and Alexander the Great. His death at the age of 52 probably saved Europe from conquest. At the time he controlled the whole Balkan peninsula and Trabzon in Asia, the last scrap of the Byzantine Empire to be wrenched from the Comnenus family. Apart from the principality of Zulcadir, the whole of Anatolia to the Euphrates was his, as were the southern Crimean ports. His two setbacks – at Belgrade and Rhodes – were avenged by Suleiman, his greatgrandson. Before that could happen, two other sultans, a skilled politician and a great warrior chief, had laid the foundations for Suleiman’s string of major victories.

Bayezid II, the son of the Conqueror, was as deeply religious as his father was sceptical and dissolute. He even destroyed or sold in the bazaar all the Italian works of art Mehmed had brought to the palace. He felt no great enthusiasm for war beyond what was politically necessary. His first struggle was with his brother Cem, who took refuge with the Knights of Rhodes after his defeat in Anatolia and became a sort of hostage of the Christian princes and the Pope. Fearing that the enemy powers could use Cem as a weapon against the Ottoman Empire, Bayezid embarked on no major offensives but put his energies into organizing the administration and developing the economy. Later sultans reaped the fruits of his efforts.

In 1495, Cem died in mysterious circumstances near Naples.17 This brought an end to the long truce which had confined Turkish military activities to routine operations in Moldavia and the area around the Danube. A war with Venice erupted at once, since the two powers were rivals in the Adriatic and the Republic dominated the coast.18 The Christians were amazed to see ships flying the sultan’s flag cutting through the Adriatic for the first time and were soon defeated in several sea battles. Mehmed II had started to build up a fleet, but Bayezid now had a far larger one,19 making the Ottomans more than a match for their adversaries.

The days when Venice could lay down the law unopposed in the Mediterranean were numbered. Lepanto surrendered to the sultan; Modon, Koron and Navarino were captured. By land, the Ottoman units of Bosnia devastated Venetian possessions as far as Vicenza. In Dalmatia and in the Aegean too, the Republic suffered major setbacks. At the end of 1502, Venice was compelled to sign a humiliating peace treaty, agreeing to give up some of the places occupied by the Ottomans and to pay tribute for Zante. It meant an end to the Venetians’ domination of the seas, although they retained their commercial privileges.

The Ottoman Empire was now a major power in the Mediterranean, the equal at sea of the nations who would for so many years be its enemies or allies: the Spanish, the French, the Venetians, and later the English and the Dutch. Its conquests in the Peloponnese could be used for further advances to the West and the North; soon privateers also joined the Turkish side, bringing ships and unparalleled experience at sea. It was during the reign of Bayezid that the Ottomans took their place on the European stage. In the Italian Wars, the Porte took the side of Milan and Naples against the French and Venetians. A few decades later, the French allied themselves with the sultan: what had once been a tiny kingdom on the steppes was now a major player in the European balance of power. It was the intelligent political manoeuvring of Bayezid II which had prepared the way.

Selim the Grim ruled only from 1512 to 1520 – but what a reign! Those few brief years saw so many decisive events – Egypt and Syria conquered, the Sophy defeated – which had so lasting an impact on the destiny of the empire that it is hard to assess Selim’s personal contribution. Only a few months after he had eliminated his enemies and his father and then defeated the last of his brothers, Selim prepared to attack Shah Ismail, the Safavid sovereign of Persia.

In a short space of time, Ismail had become the clear leader of a heretical sect formed of a strange mixture of Islamic, Kurdish, pre-Islamic and Turkish elements. Relying on the support of the Kizilbaş, fanatical Turkomans who were violently opposed to the sultan because he had encroached on their privileges (particularly with regard to taxes), Ismail had extended his territory from Eastern Anatolia as far as Baghdad and the Amu-Darya. He had stirred up revolts even in the Aegean region and had supported Ahmed, Selim’s brother, after the death of Bayezid.

There was thus every reason for Selim to try and eliminate such a dangerous enemy: a heretic of the worst kind, a trouble-maker in the Ottoman Empire and a potential ally of the European powers, which were always ready to seize any chance to destroy the enemy of Christianity. Even under Bayezid, Ismail had offered troops to the Senate of Venice to support an attack on the Ottomans. That offer had, as it happens, been refused, but they or another enemy power could certainly accept a similar offer in the future. Before taking to the field, Selim eliminated this danger by renewing a peace treaty with Venice. He also got the chief ulema (the şeyhulislam) to issue a judgement (fetva) condemning Shah Ismail and his supporters. The Kizilbaş chiefs of Anatolia were immediately arrested and executed. Then, at the head of his army, the sultan set out for Azerbaijan.

The war was no military parade. Selim’s troops mutinied several times and he came close to defeat. In the end, though, Shah Ismail joined battle at Chaldiran, in the region between Tabriz and Lake Van. On 23 August 1514, the Ottomans’ firearms gave them victory and Shah Ismail was crushed. His successors in the 16th and 17th centuries were never again willing to face the Ottomans in pitched battle.

Selim had won an immense victory. His prestige was re-established in Anatolia. But the Safavid danger had been averted rather than destroyed. Unable to root it out completely, the sultan proceeded instead, with his customary ruthlessness, against the Shiites20 of Anatolia; he took control of the few remaining areas he had not yet conquered (the principality of Zulcadir) and which gave him access to Syria, the route to the South. Finally, he subdued the Kurdish lords, who still upheld Safavid authority. In 1515, therefore, the Ottomans controlled all the principal trading and strategic routes towards Iran, the Caucasus and the Levant.

The next year, Selim decided to seal the fate of the Mamluk Empire. Learning that the sultan of Cairo, Kansuh al-Ghouri, had joined forces with the Safavids and that an army led by the Mamluk sultan had already left Cairo, Selim set out on 5 June 1516. Five weeks later, he met up with the troops led by the Grand Vizier Sinan Pasha. He ordered his men to make for Kansuh’s army, which had already marched North out of Aleppo. The battle took place on 24 August at Marj Dabik. The Mamluks were defeated and their sultan killed. Four days later, Selim entered Aleppo and, in the presence of Caliph al-Mutawakil,21 the last of the Abbasids, took for himself in the Great Mosque the title of ‘Protector of the Two Sacred Sanctuaries’ (Mecca and Medina) which had been claimed by the Mamluk sultans up to that time. On 9 October he reached Damascus and made Syria an Ottoman province – it was to remain so for four centuries. Now the road through the Nile valley was open to the Turkish conqueror.

When he had set out to fight the Ottomans, Kansuh had left Tuman Bey, one of the most respected Mamluk dignitaries, as his regent in Cairo. On the death of Kansuh, Tuman declared himself sultan and proceeded to improve Cairo’s defences. He also constructed an entrenched camp at Ridanya, which was protected with guns and ditches lined with spears. This cunning stratagem might well have proved successful if Mamluk deserters had not revealed it to Selim. He therefore changed his plans and started the battle with an exchange of artillery. The poor quality of the Mamluk cannons proved disastrous, and the ensuing mêlée soon turned to the Ottomans’ advantage. Tuman ordered his troops to retreat to Cairo, which he hoped to defend more easily with the whole population in arms behind the strong city walls.

The battle was fierce, the city conquered one house at a time. It lasted three days and nights as more and more corpses piled up in streets red with blood. On 30 January 1517, the Mamluks surrendered. Tuman managed to escape and led 4,000 horsemen in an attack on the Turkish forces South of Alexandria. Taken prisoner, he was brought back to Cairo and hanged at one of the city gates. Selim was master of Egypt. He appointed a governor and accepted the surrender of the Arab emirs, the Druze chiefs and the Christian lords of Lebanon. He reduced the customs duties and excessive rates of taxation which the Mamluks had imposed.

Now Selim, the successor of the Mamluks, was also master of the Eastern Mediterranean. He received the keys to the Holy Cities and the submission of the Sharif of Mecca. This event, which was to have profound consequences, opened a new era in Ottoman history. From now on, the sultan in Istanbul was not just the ruler of a frontier state but the sovereign chosen by God to protect the whole Islamic world. His prestige outshone by far that of all the other Muslim leaders, who were duty bound to submit to him just as he was now obliged to defend Islam against its enemies.22

Selim’s successors were able to reap the political benefits of this change; Suleiman was the first to call himself ‘Inheritor of the Great Caliphate’, ‘Possessor of the Exalted Imamate’ and ‘Protector of the Sanctuary of the Two Revered Holy Cities’. Ottoman jurists laid down the principle that the sultan had a right to the titles of Imam and Caliph because it was he who maintained the Faith and defended the Şeriat (Islamic law). Fresh obligations were thus incumbent upon the sultan of Constantinople – and the first was to extend the dominance of the House of Osman over the whole world of Islam.

The greatest of the gazi warriors, the sultan now had a responsibility constantly to advance the frontiers and laws of orthodox Sunni Islam. Religion acquired a more and more important place in the administration of the Ottoman state. In the following centuries, religion came to be controlled by a caste which, eager to retain its privileges, often acted as a barrier to the modernization of the empire. Because they always remained in contact with the earliest urban civilizations and the major currents of Islamic theology and law, and had exclusive dealings with the great Sunni religious centres, the Ottomans fought ceaselessly against every form of heresy. Yet by shutting out the Shiites in this way, they cut themselves off still further from their Asiatic origins and the civilizations of the steppes with which they had once been so closely linked.

Ottoman control of the countries of the Levant and the Nile naturally brought them pre-eminence and prestige in the Muslim world. But it also did much more. It put them in contact with the Red Sea and the Indian Ocean. It gave them greater access to the Mediterranean and North Africa and the economic and financial means which a great power needs to set out on a policy of conquest and expansion.

Selim and his successors now controlled transit centres which were among the richest in the known world. Portuguese penetration into the area, as we shall see,23 sometimes acted as a considerable nuisance in the trade between India, Malaysia and the islands of the Indian Ocean, on the one hand, and the major commercial centres of the Red Sea and Eastern Mediterranean, on the other. But such trade never came to a complete standstill. Money coming in from customs duties and various taxes levied on the passage of spices, cloth and precious goods continually made a large contribution to the resources of the Ottoman treasury. Thanks to taxes, tribute payable by local chiefs and the Ethiopian and Sudanese gold carried along the Nile, the sultans’ revenues doubled within a few years. Almost to the end of his reign, Suleiman financed without difficulty major military campaigns and countless monuments.

After his return from the Levant, Selim spent two further years in Istanbul. He reorganized the administration and devşirme system of recruitment with the same feverish activity and authoritativeness that he showed in all his activities. His major concern, however, was to modernize and build up his fleet. He built a new arsenal at Kasimpasha on the Golden Horn and enlarged those of Gallipoli and Kadirga. When Barbarossa offered to put his ships and corsairs at his disposal, he accepted without hesitation. That decision was destined to have a profound effect on the fortunes of the Ottoman Empire at sea.

When Selim died in 1520, almost all the countries to the South of the Danube – Wallachia, Moldavia and Rumelia – were already under Ottoman control. Albania and the Peloponnese had been annexed by the sultan, and the khan of Crimea was his vassal. In the Orient, the Mamluks had been crushed and Shah Ismail defeated – no further dangers remained. With the strongest army of its day and a flourishing economy, the Ottoman Empire was about to experience the reign of its most glorious sultan: Suleiman.