Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Books on Demand

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

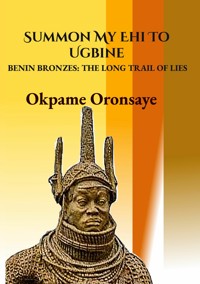

The Benin Empire flourished as an independent kingdom in present-day southern Nigeria. On February 19, 1897, a combined British Navy and Niger Coast Protectorate Force, code-named "Benin Punitive Expedition", captured Benin City, the kingdom's capital city. According to the British official statement, the "Benin Punitive Expedition" was a reprisal for the alleged killing of seven unarmed British officials on a diplomatic mission to Benin City by some Benin Chiefs on January 4, 1897, at Ugbine village, near Benin City. Today the Empire no longer exists in geographical maps, but her greatness, influence, and splendour can be still be seen in her artefacts, artworks, and mnemonics that were looted after Benin City was destroyed on February 21, 1897. Presently, over 90 percent of these Benin treasures are on display in private and public American and European museums and galleries, and in the possession of the looters' descendants. The events that led to the Invasion, looting, and destruction of Benin City, were well documented by the officials of the British Navy and Niger Coast Protectorate Authority, who played major roles in this darkest and saddest chapter of Benin history. However, for over 100 years the narratives have been retold and rewritten by American and European mainstream media, and experts and scholars of African art history and history: but sadly, prejudiced and massively distorted. Summon My Ehi To Ugbine, is based on the candid, impartial and true accounts of the events that led to the invasion of Benin City and the looting and destruction of the city, as was written by the leading actors of the episode.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 132

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

PREFACE

PREFACE TO THIRD EDITION

The third edition of Summon My Ehi to Ugbine is primarily due to the acquisition of some information about the events that led to the January 4 1987 incident at Ugbine from the Edo viewpoint, which are coming gradually into light. Iro Eweka in his book, Dawn to Dusk, shed some light on the clandestine roles played in the final phase of the events by some high-ranking Edo Ekhaemwen who wanted to ‘put the Benin king-Emperor (Omo N’Oba Ovonramwen) in trouble’. He also pointed out the driving force behind the British intentions, which was; “They (the British) had not come to make friends. They came to bully and to rob, to cheat and to steal”. Sadly. this truism is what the majority of eminent scholars(American, European and even many African) of African art history and history have refrained from mention in their discourses about the January 4 1987 incident at Ugbine. An incident that they continue claim to be “Benin Massacre”.

According to James Russell Lowell, ‘Once to every man and nation comes the moment to decide In the strife of Truth with Falsehood, for the good or evil side.’ And this moment has arrived for these scholars of African art history and history, including mainstream publications and media to decide whether they are on the side of Truth or Falsehood in their versions of the British intentions, the events that led to the “Benin Massacre”, and the destruction and looting of Benin City.

Okpame Osawamienghemwen Oronsaye January 2020 Wächtersbach, Germany

PREFACE TO SECOND EDITION

After obtaining some fresh information a slight modification has been made on a section of the book Summon My Ehi To Ugbine. Nonetheless, the main text and message remains unchanged. It is, however, worthwhile to mention that even before the publication of Summon My Ehi To Ugbine in 2016, there has been an increasing awareness in America and Europe of the wanton destruction and looting of Benin City in 1897. Indeed much earlier on there have been incessant calls for the return of the Edo people stolen treasures back to the rightful owners. These calls however gathered momentum following the action of one individual, Mr. Mark Walker. In 2014 Mr. Walker, a grandson of one of the soldiers who took part in the gruesome destruction and looting of Benin City, returned two bronzes to the Benin king-emperor, Omo N'Oba Erediauwa (r. 1979-2016). Mr. Walker is reported to have been motivated to return the two bronzes because they were described in his grandfather diary as "loot". Mr. Walker is also reported to have said, " That gave me the idea that perhaps they should go to the place where they will be appreciated for ever."

However, the narratives of the events that lead to the destruction and looting of Benin City as presented by 19th- and 20th century American and European scholars of African art history and history, publications, and mainstream media remains largely unchanged. The fable they created out of the British government official report that several unarmed British official and traders who were on a peaceful trade and mission to the Benin king-emperor were massacred by Benin chiefs continued to be re-echoed. Apparently, this fabrication seems to have become a template on which the narratives of the incident are written. Hence it is not surprising that 130 years after the incident contemporary scholars of African art history and history, publications and mainstream media still present such writings as:

“...British traders were furious that Oba (King) Ovonramwen, ruler of the still independent territory, had defied the empire and was demanding customs duties from them. Outrage back home in the UK was fuelled when a group of officers dispatched to see the Oba on the orders of the governor of Britain west African Niger Coast Protectorate were ambushed and killed.” - Museums In Talks To Return Benin Bronzes To Africa. - The Guardian, 12 August 2017.

“In 1897 a British Trading expedition arrived in Nigeria to explore the potential for conducting business with the region for various items such as Palm oil. An initial party of some 9 British officers arrived in Benin City in an attempt to open negotiation with the Oba and his Council of Chiefs. This meeting was a disaster and resulted in the death of the 9 British Naval officers.”

- Benin Bronzes. www.richardlander.org.uk

“A London punitive expedition sent to avenge the murder of British envoys conquered Benin City.” - Die Magie der Kriegerkönige: Geo Epoche Nr. 66. Afrika 1415- 1960.

Hopefully, in the near future, the actual narratives of the events that lead to the invasion, destruction, and looting of Benin City as mentioned in the book, Summon My Ehi To Ugbine, will be acknowledged by American and European scholars of African art history and history, publications, and mainstream media.

Okpame Osawamienghemwen Oronsaye August 2017 Wächtersbach, Germany

CONTENT

PREFACE

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

HIS STORY: UGBINE, JANUARY 4, 1897

THE EUROPEANS: FRIENDS & FOES

PETITIONS: MARAUDERS & MERCHANTS

UGBINE: JANUARY 4, 1897

BENIN CITY: THE SACK THAT WAS

COLONIAL OVERLORDS: THE VICTOR’S SONG

A FESTERING SORE: STILL I RISE

CREDITS

This book is dedicated to Ologbose Irabor, Ekhaemwen Obakhavbaye, Uso, Obayuwana Obaradesagbon and Oviawe, Okakuo Ebeikhinmwin, Omuada Asoro and all unsung Edo warriors who died fighting the British imperialists between January 1897 and May 1899. You are not dead. You are honoured Ancestral Spirits

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The Edo people of the Midwestern area of Nigeria believe every living thing individual has an ehi (mystical or spirit twin). The ehi ensures that the uhimwen or self-predestination of an entity lifespan on earth is carried out precisely as the entity had avowed on the day it, he or she was created by Orisa N’Oghodua, the supreme creator God. The ehi is thus perceived by the Edo not only as the guide and guard but also a witness to an entity's sojourn on earth.

Ugbine is a small town located a few kilometres west of Benin City on the Benin/Ekewan (Ekiohuan) Road. It was founded in the early 19th century as a farm settlement by Okhaemwen Ogbeide-Oyo, the then Inneh N' Ibiwe (a high-ranking functionary in the Ibiwe palace guild), hence the name Ugbine (ugbo inneh or Inneh's farm settlement).

Ugbine was thrust into the limelight of European history by an incident that took place there on January 4, 1897, which scholars and experts of African history and art history, mainstream media publications and writers, choose to refer to as the ‘Benin Massacre’. The Benin Massacre, in their opinion, was the unprovoked killing of seven unarmed British envoys and traders, who were allegedly on a peaceful mission to Benin City by a group Benin chiefs, whom they claimed were fetish and bloodthirsty savages.

Summon My Ehi To Ugbine, is neither a history reference book nor a critique of any publication of the Ugbine incident. Neither is it a personal nor an Edo view of the events that led to the alleged January 4, 1897 ‘Benin Massacre’ at Ugbine, the subsequent plundering and razing of Benin City and the reign of terror the British unleashed on the Edo people from 1897 to 1899. Summon My Ehi To Ugbine is not an expose of these events. The story has been documented and long told by those who consciously or unconsciously initiated, orchestrated and executed the tragic and painful chapter of Benin history. However for over a century subsequent storytellers: professional historians and art historians, including internationally renowned publications have retold this story, unfortunately sadly shamelessly prejudiced and massively distorted. Summon My Ehi To Ugbine is a let-the-truth be heard story. And nothing more.

My sincere gratitude to all, whose material and moral support brought this work to fruition especially, my mother Princess (Dr) Aiyevbekpen Katherine Oronsaye, my brothers and sister, Professor Jude Oronsaye, Mr. Patrick Oronsaye, Mr. Leonard Oronsaye, Ms. Consolata Oronsaye, and Mr. Damian Oronsaye, my cousins Prince Bruce Ailobafe Eweka and Prince Osahon Ogbonmwan Eweka, and my friends Dr. Sam Osarenkhoe and Mrs. Charlotte Osarenkhoe.

My heartfelt thanks to Mr Richard Ayanru who took, time to proofread the final manuscript.

My sincere thanks to Edo commentators, writers, and musicians, whose views of the Ugbine incident was food for thought. My deepest gratitude to the honest non-Edo critics, writers, and historians, who cherish and hold truth sacred, whose unbiased and objective reports helped in the search for the true account of the events that led to the Ugbine incident, and the plundering and razing of Benin City.

Okpame Osawamienghemwen Oronsaye

January 2016 Wächtersbach, Germany

‘If you tell a lie big enough and keep repeating it people will eventually come to believe it.’

- Joseph Goebbel, Nazi Propaganda Minister. (1933-1945)

HIS STORY: UGBINE, JANUARY 4, 1897

1897 Jan. 16: Capt. H.L. Gallwey, Vice Consul to Foreign Office. Reporting disaster to and failure of the Benin Expedition. CSO 3/4/1 Vol. 7. p. 1.

1897 Jan. 21: Capt. H.L. Gallwey to Foreign Office. Reporting the disaster to pacific Expedition to Benin. CSO 3/4/1 Vol. 7, p. 18.

On January 10, 1897, an urgent telegram was dispatched from the British Colony of Lagos to the British Foreign Office in London. According to the message, on January 4, 1897, the acting Commissioner and Consul-General of the Niger Coast Protectorate, Mr James Robert Phillips, and several British officials and traders on a diplomatic mission to Benin City, the capital of Benin Kingdom, were ambushed by a group of Benin chiefs. The message went on further to state that the British men, including their African porters, were taken to the city and sacrificed to the gods of the Benin king. In response to this incident, which became universally known as the ‘Benin Massacre’, the British government declared war on the kingdom of Benin. On 19 February 1897, a combined British Navy and Niger Coast Protectorate Force code-named ‘Benin Punitive Expedition’ captured Benin City. The city was plundered, and two days later the palace and royal quarters were burnt down.

Essentially for more than a century, writers, historians, especially those acclaimed as ‘eminent scholars and experts’ of African art history and history, and mainstream publications have upheld the British government official position that Mr Phillips was on a peaceful and unarmed official mission to the king of Benin, which was, ‘Phillips as acting Consul-General had to pay a necessary visit to the Benin King in order to avoid resorting to the use of force and complete every peaceful means towards resolving the economic and political impasse in the Benin River region’.

While some of these historians, publications, and writers argued Phillips mission was a diplomatic undertaking, which was made up solely of British envoys, others contended that the mission was a trade venture, which was made up solely of British traders. Some writers and publications even went on further to claim that the mission was a humanitarian venture. In the book Great Benin: Its Customs Art and Horrors, it is claimed, ‘Phillips was determined on a peaceful mission’ and the International Herald Tribune in its January 13, 1897, issue stated, ‘The (Phillips) expedition was quite unarmed and was endeavouring to enter by peaceful means the king’s city (Benin)’. In some books and publications such as Treasures of Ancient Nigeria, Black Africa: Masks, Sculpture and Jewellery, and Encyclopaedia Britannica (1911 edition) the assertions are that Phillips was on a routine visit to the king of Benin. And some other publications such as, Royal Art of Benin: The Perls Collections and The Story of Nigeria, the contention is that Phillips was on a mission to discuss trade agreement with the Benin king, and while in the book, Benin: Kings and Rituals the contention is, ‘… it (Phillips party) was a peaceful mission, which wanted to persuade King Ovonramwen to keep to the terms of trade agreement that was concluded in 1892’. While in its January 16.1897 publication, The New York Times claimed that the Phillips party was a ‘British Commercial Expedition’.

The Time Magazine in an article, ‘City of Blood’, in its December 16, 1935, issue, portrayed these views colourfully. And according to the publication, ‘Britain was eager to trade with forbidden Benin in the interior and acting Consul General Phillips had sent a message to grinning black King Overami (Ovonramwen) of Benin, asking permission to visit his capital to arrange a treaty’.

Some publications, however, contend that Phillips was on a mission to demand an end to the customs duties collected from British traders by the Benin king. And as stated by The New York Times in its January 22, 1897 issue, ‘the Phillips mission was to persuade the Benin king, who had threatened death to any white men who attempted to visit him, to remove obstacles he was putting the way of trade’.

However, in an article, Benin: The Sack That Never Was, the writer claimed, ‘A large part of the purpose of the Expedition (Phillips) was to suppress the practice of human sacrifice’. And this was the same view adopted by the Time Magazine, in the article ‘The Bronzes of Benin’ in its August 6 1965 issue, which was, ‘Objecting to the sale of slaves and human sacrifice, a consul general set out in 1897 with eight men to halt the annual ritual of slaughter’. This alleged humanitarian mission was further amplified in the book, The Village of Ghosts where it is claimed, ‘Phillips was appalled by the human sacrifice in Benin City and was determined to visit Benin City and persuade the Benin king to abolish it’. Even, according to a Nigerian researcher, U.O.A. Esse, ‘The conquest of Benin in 1897 completed the British occupation of south-western Nigeria. The incident that sparked the expedition (Benin Punitive Expedition) was the massacre of a British consul and his party, which was on its way to investigate reports of ritual human sacrifice in the city of Benin’. Then one other publication claimed, ‘In 1896 a small armed force from the Oil River Protectorate led by the governor entered Bini (Benin) territory to talk to their ruler about ending slavery and human sacrifice...’ Incidentally Captain Boisragon, Commandant of the Niger Coast Protectorate Force and one of the survivors of the alleged ‘Benin Massacre’, in his book, The Benin Massacre, wrote: ‘The object to the expedition was to try and persuade the king to let the white men come up to his city whenever they wanted to’.