19,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Fachliteratur

- Sprache: Englisch

T. Rowe Price, the Sage of Baltimore In 1937, Thomas Rowe Price, Jr. founded an investment company in Baltimore that would become one of the most successful in the world. Today, The T. Rowe Price Group manages over one trillion dollars and services clients around the world. It is among the largest investment firms focused on managing mutual funds and pension accounts. Uniquely trusted and respected, the firm is considered the "gold standard" by many investment advisors. In this book, Cornelius Bond tells the full story, for the first time, of how Price, a modest and ethical man, built the company bearing his name. From the private, unpublished personal and corporate records, you will get direct access to the creative process behind Price's highly successful approach to investing. * Personal insights based on Price's own writings and the personal experience of the author who worked with him for many years. * The Growth Stock philosophy as described in the words of the creator and master of this approach. * Two fund managers who worked closely with Mr. Price reunite to consider the investment environment of the next five to ten years as Price himself might have viewed it. This book will give you an insider's access to the true story of Thomas Rowe Price, Jr.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 448

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

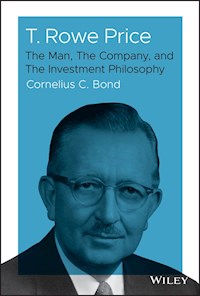

T. Rowe Price

The Man, The Company, and The Investment Philosophy

CORNELIUS C. BOND

Copyright © 2019 by Cornelius C. Bond. All rights reserved.

Published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey.Published simultaneously in Canada.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per‐copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750–8400, fax (978) 646–8600, or on the Web at www.copyright.com. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, (201) 748–6011, fax (201) 748–6008, or online at www.wiley.com/go/permissions.

Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and author have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. No warranty may be created or extended by sales representatives or written sales materials. The advice and strategies contained herein may not be suitable for your situation. You should consult with a professional where appropriate. Neither the publisher nor author shall be liable for any loss of profit or any other commercial damages, including but not limited to special, incidental, consequential, or other damages.

For general information on our other products and services or for technical support, please contact our Customer Care Department within the United States at (800) 762–2974, outside the United States at (317) 572–3993, or fax (317) 572–4002.

Wiley publishes in a variety of print and electronic formats and by print‐on‐demand. Some material included with standard print versions of this book may not be included in e‐books or in print‐on‐demand. If this book refers to media such as a CD or DVD that is not included in the version you purchased, you may download this material at http://booksupport.wiley.com. For more information about Wiley products, visit www.wiley.com.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is Available:

ISBN 9781119531265 (Hardback)ISBN 9781119531289 (ePDF)ISBN 9781119531319 (ePub)

Cover Design: WileyCover Image: Photograph by Bachrach

“They come and they go – with brief torrents of publicity and a moment or two of glory on the Lipper sheets. But few money managers, very few, stand the test of time. One of the handful that has is the Sage of Baltimore, 77‐year‐old T. Rowe Price, Jr.”

“Why T. Rowe Price Likes Gold,” Forbes, October 15, 1975

Table of Contents

Cover

Foreword

Acknowledgments

Part One: THE BEGINNING

Chapter One: THE HOUSE ON DOVER ROAD, 1898–1919

Chapter Two: LESSONS LEARNED, 1919–1925

Chapter Three: MACKUBIN, GOODRICH & CO., 1925–1927

Chapter Four: THE GREAT BULL MARKET AND THE CRASH, 1927–1929

Chapter Five: AFTER THE CRASH, 1930–1937

Part Two: HIS OWN BOSS

Chapter Six: BIRTH OF T. ROWE PRICE AND ASSOCIATES, 1937

Chapter Seven: “CHANGE: THE INVESTOR'S ONLY CERTAINTY”

Chapter Eight: THE FIRM'S ADOLESCENCE AND WORLD WAR II, 1938–1942

Chapter Nine: THE GROWTH STOCK PHILOSOPHY

Chapter Ten: POSTWAR ERA, 1945–1950

Part Three: THE SAGE OF BALTIMORE

Chapter Eleven: NEW OPPORTUNITIES: MUTUAL FUNDS, PENSION PLANS, AND THE LAUNCH OF THE GROWTH STOCK FUND, 1950–1960

Chapter Twelve: TRANSITIONS, 1960–1968

Chapter Thirteen: THE UNITED STATES ENTERS A NEW ERA, 1965–1971

Chapter Fourteen: DARK NEW ERA, 1971–1982

Chapter Fifteen: THE GRIN DISAPPEARS, 1972–1983

Part Four: MARKET ANALYSES

Chapter Sixteen: INVESTING FOR THE DECADE, 2017–2027

Chapter Seventeen: WEAK PERFORMANCE OF THE GROWTH STOCK FUND, 1970s

Epilogue: T. Rowe Price Today

Sources

Index

End User License Agreement

Guide

Cover

Table of Contents

Begin Reading

Pages

iii

iv

v

ix

x

xi

xii

xiii

xiv

1

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

121

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

158

159

160

161

163

164

165

166

167

168

169

170

171

172

173

175

176

177

178

179

180

181

182

183

184

185

186

187

188

189

190

191

192

193

195

197

198

199

200

201

202

203

204

205

207

208

209

210

211

212

213

214

215

216

217

218

219

220

221

222

223

224

225

226

227

228

229

230

231

232

233

234

235

236

237

238

239

240

241

242

243

244

245

246

247

248

249

250

251

252

253

254

255

256

257

258

259

Foreword

Thomas Rowe Price, Jr. developed the “Growth Stock Philosophy” of investing in the 1930s. His innovative ideas captured the imagination of a Barron's editor who asked him to write a series of articles, published by the magazine in the spring of 1939. Adhering to this philosophy, he successfully invested his clients' money at his new firm for sixteen years. By 1950, his success gave him the confidence to introduce his first mutual fund, the T. Rowe Price Growth Stock Fund, consisting of large well‐established growth companies. Ten years later, he started the New Horizons Fund to invest in emerging growth companies earlier in their life cycle. The Growth Stock Fund ultimately produced the best performance record through its first ten years of any U.S. equity mutual fund, with the objective of growth, income secondary. New Horizons had the best performance for its first five and ten years of any U.S. equity mutual fund. This is according to Investment Companies by Arthur Wiesenberger, the source for mutual fund performance data at that time.

The firm that bears his name has grown to become one of the largest companies in the business of actively managing money in the United States, with more than $1 trillion in assets under management as of March 31, 2018.

The T. Rowe Price Group today still operates under many of the basic tenets of the Growth Stock Philosophy, including a focus on the longer term, a strong emphasis on fundamental research, and the belief that knowing and respecting management are key factors in buying the shares of any company. In 2017, the firm continued its long record of outstanding performance with 81 percent of all mutual funds beating their respective Lipper averages on a total return basis over ten years, according to the firm's 2017 annual report.

An important contributor to this book is Robert (Bob) E. Hall, who worked with me at T. Rowe Price Associates for more than ten years, during which he was chairman of the Investment Committee of both the Growth Stock Fund and the New Era Fund. He later joined Brown Capital Management and co‐founded the Small Company Fund. According to Bob, this fund has been run since inception under the tenets of Mr. Price's Growth Stock Philosophy. In 2015, Morningstar awarded Bob and his team the title of Domestic Stock Fund Managers of the year. The Morningstar announcement mentioned that the fund's performance was in the top ten percent of all U.S. mutual funds for the previous three, five and ten, years – and since Morningstar was launched in 2011, as measured by Morningstar's five‐star rating.

It is apparent that this philosophy of managing money is as valid today as it was when Mr. Price introduced it eighty years ago. It will be discussed in detail in the following pages. Its deceptively simple concepts are based on common sense or “horse sense,” as his grandmother used to say. Mr. Price, however, was hardly an amateur investor and had more than a usual level of investment common sense. Little has been written about how this modest, ethical man managed to build one of the largest U.S. companies in the business of managing mutual funds. Yet his record of stock market performance over his long career places him among the top money managers of the twentieth century.

He also had an amazing ability to forecast the long‐term trends in society, politics, and the economy that impacted the stock market. His analysis of these trends allowed him to take positions at favorable prices well before other investors became aware that a change had occurred. He believed that a serious investor should consider these long‐term trends from time to time and adjust his investments accordingly. Mr. Price issued his last detailed forecast in 1965, in which he foresaw the coming runaway catastrophic inflation that did, in fact, occur in the 1970s. He started the New Era Fund to produce excellent results in this environment, wherein gold went up more than twenty times and mortgage rates exceeded eighteen percent. A suggested outlook for the next decade, based on the use of Mr. Price's long‐held ideas and concepts as well as the author's inputs of current data and major changes, is discussed in detail, and brought up to date, in Chapter 16.

A memorial in the November 21, 1983, issue of Forbes stated: “[Price] never achieved the influence of the late Benjamin Graham because, unlike Graham, Price was not an articulate man.” He hated to give speeches and was not good at delivering them. He was impatient with reporters who failed to quickly understand his ideas. His writings, however, were clear and well thought out.

One of my first assignments as a young analyst at what was then T. Rowe Price and Associates was to interview the management of Hewlett‐Packard in Palo Alto, California. I had used the company's reliable, well‐built electronic instruments as a Princeton undergraduate engineer, working in the university labs, and, later, working for Westinghouse Electric Corporation as an electrical engineer. Fortunately for me, my contact had been called out of town and the legendary David Packard took his place as a pinch hitter. Having built one of the great growth companies in the world, he explained to me how he did it, sitting in his functional, simply furnished open office.

Being an engineer himself, he used his original pencil‐drawn charts to demonstrate what he had learned when he looked back over the company's growth from its inception in 1939, twenty‐one years before. Each product started slowly, grew rapidly, and tapered off in maturity, ultimately declining in old age.

Mr. Packard learned from these charts that the key to building a successful company (which Mr. Price would call a “growth company”) was to introduce new products on a regular basis over time. This continual need for new products opened Packard's eyes to the extreme importance of productive research. He also realized that Hewlett‐Packard had to generate enough profits to pay for growth in facilities, inventories, and personnel to cover the costs of physical growth. After this analysis, he substantially increased spending for research. It emphasized to him where top management should be spending much of its time.

In fact, I later learned that Mr. Price had first called his new theory of investing “the life cycle method of investing.” He had also realized, from his experience at DuPont, that if new products weren't continually introduced, the whole company would follow its natural life cycle and quickly sink from growth into maturity.

Although the growth of a company in any one year can appear to be trivial, the magic of compound growth over the long term can produce astonishing investment returns. A little more than seven percent compound growth (seven cents on every dollar) doubles sales and earnings in ten years. A fifteen percent growth, typical of Hewlett‐Packard in the 1960s, doubles sales and earnings in just five years. This is the real secret of investing in growth stocks.

One of the world's most successful investors, Baron Nathan Rothschild, is said to have called compound interest “the eighth wonder of the world.”

In this book, I describe how Mr. Price recognized companies that produced superior growth over long periods of time, tell the story of how his company grew, and provide an insight into Thomas Rowe Price, Jr., the man.

Acknowledgments

First, I would like to thank the many individuals at T. Rowe Price, both active and retired, whom I interviewed for this book. They were uniformly professional and pleasant, a hallmark of the firm's personality when I joined it nearly sixty years ago. I also thank the others who gave me advice, helped with the editing, and answered critical questions during the course of writing this book.

I am indebted to Mr. Price's son, Thomas Rowe Price III, who reviewed some of the early family history in the book and explained a little about the farm where Charles “Charlie” W. Shaeffer and Mr. Price developed plans for the company's future.

I have mentioned Bob Hall in the foreword; he was my major contributor, friend, and support, particularly when problems arose that might have ended the project.

George A. Roche was also a major contributor and friend throughout, sharing commonsense advice as well as his insight into the thinking of Mr. Price, with whom he was close, particularly in Mr. Price's declining years.

Austin George, who graduated from Princeton a year before I did and joined the firm in 1959, also a year before me, was the fourth member of our small informal group who saw the project through from beginning to end and added thoughtful input, particularly on the early days of the firm and from his position as head of equity trading.

Joseph A. Crumbling, Chief of Staff, Office of the President and CEO, patiently stewarded the project through the alleys and byways of the company's administrative structure and is owed special thanks.

After his many years as a T. Rowe Price research analyst and portfolio manager, thanks to Preston Athey for his patient and thorough editing of the book after its initial completion, with his in‐depth knowledge of the firm and the people mentioned in the book.

A special thanks to Jim Kennedy, who got behind the book project at its inception and provided excellent advice along the way. Jim retired as CEO and president of T. Rowe Price halfway through the writing of the book. He was succeeded by Bill Stromberg, who was also a great help, particularly in the writing of the epilogue, which is about the Price firm of today.

Truman Seamans' amazing recall of his 70 years at the epicenter of Baltimore business was a great help in understanding the people and organizations that made it all work.

I also want to acknowledge Theresa Brown, who transcribed hours of my dictation and worked through the difficult task of interpreting my handwriting to produce a first draft.

Karen Malloy was the first statistician for the New Horizons Fund and came out of retirement to develop the statistics found in Chapter 17, which required many hours of compiling ancient financial data.

Kate Buford also edited the book, having written biographies herself. She managed to maintain her calm and good advice despite my less than deferential remarks when I found some of my “best” passages on the cutting room floor.

Steve Novak put his skills as a former analyst for Naval Intelligence and his passion for genealogy and biographical research to good use in performing a great deal of the research and fact checking, as well as developing the annotations for the book.

I am indebted to Richard (Rich) Wagreich, who, with his background at Goldman Sachs and the Federal Reserve, and his experience at T. Rowe Price, helped me with many of the economic statistics used in the book.

Also, my unofficial editor, Stephanie Deutsch, devoted many hours in instructing me in the fine art of the biography. She is an excellent biographer in her own right.

A special thanks to Ann O'Neill, a long‐time resident of Glyndon and expert in its history.

All that said, any errors in this book are mine alone.

Finally, but most importantly, I am grateful to my wife, Ann, who reorganized our lives for the last five years to allow me the time to devote to this book.

Part OneTHE BEGINNING

Chapter OneTHE HOUSE ON DOVER ROAD, 1898–1919

A soft orange glow from oil lamps could be seen through the first‐floor windows of the house at 4801 Dover Road in the small town of Glyndon, Maryland. The flickering light illuminated the branches of the trees dancing to the force of the cold northeast wind. At this early hour, the lamps provided the only light on the street. It had been raining the day before and puddles remained on the hard dirt surface of the street, bordered by wooden sidewalks.

A rooster prematurely announced the dawn as the soft whinny of a horse came from the stable behind the house. Suddenly the sound of a slap on a wet baby's bottom emanated from the interior of the home. It was March 16, 1898, and Thomas Rowe Price, Jr. let out his first cry as his father, Dr. Thomas Rowe Price – the only doctor in town – brought him into the world. He was swaddled in a warm blanket and placed in the arms of his mother, Ella Stewart Black Price, who settled back for a well‐earned rest.

The above account is as imagined by the author after visiting the original house in which Mr. Price was born and following discussions with several local residents, one of whom was delivered by Mr. Price's father and another of whom is an active member of the historical society.

Mr. Price's mother, Ella Price, born 1869. TRP archives; photo owned by Mrs. Margaret Moore, wife of Dr. Moore, Mr. Rowe Price's nephew.

Mr. Price's father, Dr. Thomas Price, born 1865. TRP archives; photo owned by Mrs. Margaret Moore.

Every summer Rowe's future paternal grandfather, Dr. Benjamin F. Price – also a physician – and grandmother, Mary A. Harshberger Price, enjoyed the beach at Ocean City, Maryland. That is where Thomas Price met Ella Black following his graduation from medical school. It was love at first sight for both of them. They were married in 1893 and moved into a new house on Dover Road, a wedding gift from Ella's new husband.

Dr. Price's original home, where he delivered all of his children; built 1893; photographed in the nineteenth century. TRP archives; photo owned by Mrs. Margaret Moore.

It was a large house for the time, with three floors and a square tower on the side, in keeping with the Victorian style of architecture. On the first floor were a large dining room, a living room, and a kitchen in the back overseen by the cook. A handsome staircase led up two flights of stairs to the bedrooms and a large sleeping porch for hot summer nights. Also on the first floor were Dr. Price's office and a small laboratory off the office where he concocted his medicines. Friends who came to call would enter through the front door and chat with him in his office. Patients would enter and leave through a back door if they needed a physical examination or treatment in his examining room. In those situations, one did not want to advertise serious illness, as the odds of recovery were much lower than today.

Medicine bottles used by Dr. Price. Author's photo.

In the spacious backyard, shaded by tall oak trees, were a carriage house, a barn, and a stable where Dr. Price had two horses, buggies, harnesses, and a cow for milk. In lieu of indoor plumbing, the family used a generously sized outhouse with different‐sized cutouts for different ages. The large front porch was close to the sidewalk and had a comfortable swing. On warm nights the Prices, as well as their neighbors, would sit on the porch and gossip with those who were strolling down the sidewalk. Often singing could be heard from the other houses nearby, with a piano as an accompaniment.

There was plenty of space for Rowe, his older sister, Mildred, and his younger sister, Gahring, who would arrive five years later, as well as his maternal grandfather, Samuel Black, and his grandmother, Margaret Catherine Grubb Black. These grandparents lived with Dr. Price and his family from the time Rowe was two until their deaths in 1910.

Samuel Black had a significant influence on the young, impressionable Rowe. He was a successful entrepreneur involved in real estate – the major investment opportunity for most people at the turn of the century – as well as home construction throughout Baltimore County. His assets in the 1870 census were listed as $70,000 ($1.7 million in 2018 dollars). Today, one is conservative in listing assets for the census taker and this was also likely true at that time. Moreover, Black continued to be an active real estate developer for many more years and didn't retire completely until he moved in with his son‐in‐law. In the 1930s, when Rowe was first describing his Growth Stock Philosophy, he would say, “to find a fertile field to invest in you didn't have to go to college, you only needed what my grandmother called horse sense.”

Mr. Samuel Black, Mr. Price's grandfather, born 1824. TRP archives; owned by Mrs. Moore.

Mrs. Margaret Black, Mr. Price's grandmother, born 1830. TRP archives; photo owned by Mrs. Moore.

Glyndon was a lovely rural town 20 miles northwest of Baltimore with a winter population of about 300. In the summer months, it more than doubled in size, as people fled Baltimore's heat, seeking relief in the relative coolness of the country. The town was perched 750 feet above sea level, considerably higher than nearby Worthington Valley. This elevation helped to cool the air, particularly in the evening, making for better sleeping on hot nights.

According to Glyndon: The Story of a Victorian Village, the town was founded and named in 1871 when the track of the Western Maryland Rail Road (which became the Western Maryland Railway in 1910) from Baltimore stopped there rather than proceeding on to Reisterstown, where the city fathers had refused to have the railroad enter its city limits. The railroad caused the town to grow. It was easy for visitors to come out from Baltimore on day trips and for the men of the community to commute into Baltimore for work. And grow it did, for the next forty years, into large grassy neighborhoods of stately homes with gables, wide verandas, and big sleeping porches.

To the small population of year‐round residents and the wealthy summer crowd were added two camps that were famous locally. They ultimately became well known nationwide and likely would have an important influence on the values of young Rowe. The largest and best known, Emory Grove, was named after John Emory, a Methodist Bishop born in Maryland in 1789. One of the founders of Methodist theology, he rode through the state on the circuit, preaching the Christian gospel. Education was also very important to Emory. He was one of the founders of Dickinson College and Wesleyan College, and Emory University in Georgia is named for him. The camp occupied 160 acres of rolling wooded land. Intended as a quiet retreat away from the “madding crowd,” it was far from quiet. With accessibility provided by its own railroad stop, the camp grew significantly in popularity. The beauty of the setting, and the frequent appearance of famous preachers such as Billy Sunday, drew thousands over summer weekends. In June 1895, it was reported that 10,000 people came to Emory Grove to hear another well‐known preacher of the time, Eugene B. Jones, speak. For those who required at least modest comfort, there were four hotels and more than 700 tents for the rest. The days were given to religious services and teaching, and many nights to the singing of hymns. It is no accident that Rowe and his sisters would grow up as Methodists. On other nights, the younger set took over with parties, games, and much laughter. Although winter evenings were quiet for the Price family, the Grove provided a lot of social activity in the summer. Rowe was acclaimed in his high school yearbook as being a good dancer, presumably based on the practice he got at the Grove.

Close to the Price house was the temperance summer camp run by the Prohibition Party. Mandating total abstinence from alcohol and its “evil” effects, the camp was set up on 18 acres and everyone lived in tents. There was a natural bowl formation on the property, making it an excellent amphitheater where thousands could listen from the grassy slopes. Many good orators spoke there, including members of the Prohibition Party, which ran candidates for U.S. president and was an active third party in the early 1900s. Other entertainment included concerts, poetry, and lectures on many subjects. As Prohibition declined in popularity later in the 1920s and was finally repealed in 1933, the camp adopted the entertainment and educational model of the more famous Chautauqua assembly in New York State. Rowe's father never allowed alcohol or wine in the house.

To paint a picture of life in Glyndon at the time, below are excerpts from Glyndon: The Story of a Victorian Village, in which one of the authors, Jean Wilcox, describes an average day in the summer around the turn of the century:

Days followed a carefree pattern. In the morning we were up early to have breakfast with Papa before he took the 8:05 train to the city and work. Then came the day's chores. The children filled the oil lamps; the mothers canned fruits and vegetables or possibly worked in their flowerbeds.

Everybody in the town retired to the second floor from 2 until 3:30 p.m. The shutters were closed and the streets were deserted and quiet. [Later] the young people played croquet on the front lawns or tennis, while the mothers strolled the boardwalks or met on each other's porches to talk or rock. The town's lively air was largely due to the fact that each street took on a social atmosphere in the afternoon

The Big Event of the afternoon was the walk to the Western Maryland Station to meet Papa who came home on the 5:50 train from Baltimore with other working husbands and fathers. Most of Glyndon turned out at the station every day.

After supper, we amused ourselves with parlor games or recitations.

Glyndon was an active center for sports of all kinds. An ardent Glyndon tennis player was Edmund C. Lynch, whose family summered in the town around the turn of the century. Later one of the founders of Merrill Lynch, he was thirteen years older than Rowe. Though there is no indication that they knew each other well, Eleanor Taylor, an elderly Glyndon resident who had been delivered by Dr. Price some ninety‐two years earlier, recalled that Rowe and Ed often crossed racquets on the grass courts during summer afternoons. Rowe greatly enjoyed the sport and would be an active player until his later years. Lynch, and his later success at Merrill Lynch, may have had some influence in steering Rowe into finance.

One of Samuel Black's grandsons, Rowe's first cousin, was S. Duncan Black, the founder of Black & Decker. Begun in 1910, the company would become one of the leading worldwide electric tool manufacturers for the home improvement market. Growing businesses was apparently in the genetic makeup of the Black family.

Dr. Price's career path differed from that of his father‐in‐law, whose singular interest was business. Rather than heading to medical school right after high school, Dr. Price taught school for several years, as had his own father, before deciding to go to the University of Maryland's medical school. He graduated in 1891, at the age of twenty‐six, and moved to Glyndon to establish his practice.

Helping his clients achieve financial health would be very important to Rowe and a fundamental reason he founded his company. Money was also important to him, but in moderation, so that he and his family could enjoy a comfortable life. He would never drive an expensive car or live in a very large house.

Dr. Price was a good, traditional country doctor, according to Eleanor Taylor. He treated his patients wherever they got sick, often traveling in the evening to distant farms in all kinds of weather. He was fond of telling the tale that after his last call on cold, dark nights, he would often snuggle down into the blankets in his buggy, wrap the reins around the whip handle in its socket, cluck to his horse to begin the trip back, go to sleep, and wake up when the horse stopped at the door to his Dover Road stable. Over the years, Dr. Price became highly recognized in his profession. He was appointed surgeon to the Western Maryland Rail Road that serviced Glyndon, and was also named the Health Officer for Baltimore County, an important honorary post and one that his father had been granted years before. He was a director and then treasurer of the Glyndon Permanent Building Association, an organization of volunteers that provided financing for homes in Glyndon before banks came to the area, and an elected board member of Emory Grove. According to Eleanor Taylor, he was a gentleman, quiet and highly professional. He reportedly had a competitive side that he passed along to his son. According to Mildred's son, Rowe, he had the biggest sled in town, which could outrun any other on its long runners. Dr. Price also did well financially. By 1918, he listed his holdings as 73 acres, three homes, a tenant house, a stable, sheds, two barns, three cars, and a truck.

Rowe's mother, Ella, was a strong‐willed woman and the youngest of seven children. Like her husband, she was well respected in the community and a founding member and the first vice president of the Woman's Club of Glyndon. Originally, this group reviewed books for discussion and was involved in various social activities locally, but as it grew in membership it became committed to more important civic issues. In 1902, the club was responsible for bringing electricity to Glyndon. Later, it created street signs and instituted garbage collection. One could speculate that Ella Price was likely a strong mover behind these activities, given her reputation for drive and getting things done. When a fire destroyed the meeting room of the Woman's Club in the Methodist Church of downtown Glyndon in 1932, Dr. Price would buy the old two‐room schoolhouse to provide a permanent home for the club. It took some courage and the urging of a very determined wife to make such an investment in the depths of the Great Depression.

Rowe was sent off to elementary school at Glyndon School (the same schoolhouse Dr. Price would later buy) at the age of five. As was true until he got to college, he was the youngest member of the class. It was fairly easy for him to walk the mile or so, or to ride the trolley, which ran down Butler Road (Dover Road had become Butler Road by then, which it remains today) in front of his house. His older sister, Mildred, accompanied him. Glyndon School was a red brick two‐room structure with a cedar shake roof and a large bell tower. The interior of the school was grim, with practical brown paint decorating the walls. The rope to the bell hung below the tower and it was fun to pull on the rope when you were asked, but woe to the child who pulled it out of turn. In general, the classes were well disciplined and quiet, at least in the upper grades. Rowe went to first and second grade in the room on the north side; the other, larger room was for the third through the sixth grades. There were two teachers, with the upper‐grade teacher also acting as principal. The alphabet and reading were taught in the first two grades; the multiplication tables weren't taught until the fifth grade. The teachers were strict and a firm rap on the knuckles could be expected if one forgot the product of two numbers. Writing was learned by long practice with handbooks and scratchy straight pens that were dipped into inkwells planted on the desk.

Mr. Price's first school, Glyndon Elementary School, built 1887. Glyndon Historical Society.

In 1909 Rowe graduated from elementary school and entered Franklin High School in Reisterstown. Under the supervision of his sister Mildred, they made their way to and from school by electric trolley. In his sophomore year, there was a school‐wide tennis tournament consisting of fourteen students; Rowe finished second. His years of practice on the grass courts of Glyndon had stood him in good stead. His high school nickname was Doc, suggesting that he intended to follow in his father's footsteps. In his first year there were more than sixty students in his class. By graduation, this had been whittled down to twenty‐three. In later years, Rowe would proclaim that he was “not much of a student,” but he certainly had the willingness to work and the ambition to do at least well enough to get through and graduate in a class with a 60 percent attrition rate.

Mr. Price's older sister, Mildred Price, born 1895. Photo owned by Mrs. Margaret Moore.

He was well liked at Franklin, a bit of a cutup, and the humor editor of the yearbook. The comments under his yearbook photograph read, “His legs are long, he is very tall and ever has a good word for all,” and “It is only his tender years that have saved him from being reprimanded for his pranks at school. His specialty is teasing the girls.” The editor (most of the editorial staff were girls) added, “A day spent at school without Rowe would be a day lost,” and “When he was on the program [Rowe was a member of the Franklin Literary Society] we all looked forward to being highly entertained.”

He was only sixteen when he graduated from Franklin, and his parents decided to send him to the Friends School of Baltimore as a postgraduate student, presumably, to ensure that he got into a good college. Founded by the Quakers in 1784, the school when Rowe attended it was located at 1712 Park Avenue, next to the Friends Meetinghouse (today it is located on Charles Street). Friends remains one of the oldest private high schools in the country. The classes were also small, typically with twelve students, which allowed for a strong interaction with the teachers. At the end of the year, in 1915, Rowe did not finish at the head of the class, according to “T. Rowe Price: A Legend in the Investment Business,” the Baltimore Sun, October 22, 1983, but did well enough to be one of three who were accepted at Swarthmore and the only one of them to graduate from the college.

Swarthmore was an easy choice. His sister Mildred was already enrolled there, it was relatively close to Glyndon, and it had small classes and an excellent academic reputation. It was founded in 1864 by the Quakers, although students of other religions were accepted. In 1906 it formed its own administration and was no longer directly managed by the Quakers. In 1915 many of the qualities of the Quaker church, such as austerity and simplicity, still remained. As a school, it would have seemed like Friends School: the student‐to‐teacher ratio was only eight to one and the overall Quaker philosophy was similar.

When Rowe first traveled to Swarthmore to enter college that fall, he probably took the train from Baltimore to Philadelphia, from which he would have continued on another train some eleven miles up the Main Line. Mildred would either have come with him or would have met him at the station on the edge of the campus.

The Pennsylvania climate could be harsh, so the school was a cold and bleak place in the winter. The original hot‐water radiators were no match for the wind and snow. Heavy sweaters and jackets were the norm, worn daily both inside and out. But on his initial arrival on that autumn day, it was an easy walk through beautiful stands of oak, sycamore, and elm to the lower campus. His arrival is as imagined by the author after a visit to the Swarthmore campus on a bright sunny day early in the fall semester:

Rowe and Mildred walked through the trees from the station to the Magill Walk, lined with oak trees, up the grassy slope to Parrish Hall, built on the top of the hill. They passed small groups of students picnicking and gossiping about their summer and the year about to begin. The bright dresses of the women were splashed with sunlight, adding color to the scene. Parrish Hall, where they signed in for the new school year, was a large building made of locally quarried gray stone. Other than white paint outlining the windows and doors, Parrish Hall, true to its Quaker heritage, was completely unadorned, with none of the Victorian curves and embellishments so popular elsewhere in the early twentieth century. A broad porch supported by white wooden columns extended across a portion of the facade. Students were gathered there, in lively conversation, filling out papers and class requests.

Rowe arrived at Swarthmore with the full intention of becoming a doctor. Not surprisingly, the major reason, according to Mildred's son, Rowe, was due to Dr. Price's strong, unrelenting sales pitches over many years. As the only son, Rowe bore the full brunt of his father's campaign for him to become a physician. It is not certain why he decided not to follow the family tradition. With customary modesty concerning personal matters, he would attribute his change of heart to poor marks. Whatever the reasons, he switched to chemistry in his junior year. Possibly he felt that such courses were an important part of a premed degree and essential subjects for a budding doctor, so credits here might have helped if he later changed his mind and decided to go to medical school. Or perhaps it was to help his relationship with his father. Chemistry was also then one of the major technologies of the future at the dawn of the twentieth century.

Mr. Rowe Price, Swarthmore College junior yearbook, 1918. Swarthmore College.

Despite the large offering of subject matter at Swarthmore, Rowe did not take a single course in either economics or business. When he left college, he was a chemist by training and believed that chemistry would be his career. Although he was referred to as “the electrician” in his Franklin High School yearbook, Rowe never fully developed an interest in the science of electricity at Swarthmore. But in the summer of 1916 he did electrical work at Emory Grove and was paid the large sum of $18.85.

Mr. Rowe Price, Swarthmore College senior yearbook, 1919. Swarthmore College.

A comparison of Rowe's graduation pictures from Franklin High and Swarthmore College shows a clear physical maturation in his college years. Active in athletics, he was the manager of both the football and swimming teams. It was in lacrosse, however, that he excelled. Not only was he on the varsity team in his senior year, for which he won his letter, but, based on reports in the school paper, he became a star player toward the end of the season. He was also active outside of sports. He was a photographer on the yearbook staff, played a major role in the school play, was president of the junior class, and joined the Delta Upsilon fraternity.

By his senior year he had come into his own and was considered to be one of the “big men on campus,” in a phrase of the time. In that era, it was not unusual for a number of students to drop out before completing four years of college. Rowe most likely felt a sense of accomplishment to graduate in 1919, because, as he told us “juniors” at the firm, he was the only student of the three that had been accepted from Friends that year to graduate.

In his later years, Rowe would not appear particularly religious. He did go to church and would later become a Presbyterian, but it would not be a major part of his life. Still, in an interesting way, the adult Rowe would seem to incorporate the values of the “Quaker Way,” and such qualities were certainly part of his family upbringing. He believed in hard work. He was never ostentatious. He believed in the value of women in the workplace. As advocated by Quakers, Rowe would practice all of his life the exercise of both mind and body, and he would be an independent thinker of the first order.

Perhaps most importantly, integrity – beginning with his own personal integrity – would be a guiding principle of the firm that he would form many years later, at a time when integrity would be in short supply in the financial world. As a Securities and Exchange Commission lawyer would comment later to Walter Kidd, one of the founders of T. Rowe Price, “T. Rowe Price and Associates was the gold standard” when it came to its conduct toward its clients.

Chapter TwoLESSONS LEARNED, 1919–1925

The following fictional account describes how Rowe might have been introduced to his first job, shortly after graduation from Swarthmore. It is based on photographs of the plant, an interview with Ralph Mehler of the nearby town of Sharpsville Historical Society in Pennsylvania, and the author's experience working at Westinghouse Electric at its oldest plant, then located on Turtle Creek in Pittsburgh. The basic facts are accurate, such as location of the plant, its size, and the principal characters. Only the words of the conversations are completely made up.

Rowe and his fraternity brother Lindsay Cornug stepped off the train into the summer heat of western Pennsylvania in 1919. They had arrived in Leechburg, a small town of four thousand souls planted on the banks of the polluted Kiskiminetas River. The town earned its living by building products made of the steel produced in large quantities in Pittsburgh, thirty‐five miles to the west. The men's immediate destination was the Fort Pitt Enamel and Stamping Company.

The air was thick and humid with an industrial haze and a faint smell of sulfur.

The two young men looked at each other. Rowe rubbed a tear from his eye. For a moment, he could not figure out why he was crying. Then he realized it was from the chemicals and other pollutants in the air. It was certainly very different from the clear blue skies and tree‐shaded campus at Swarthmore.

They found the company right on the river. It was early afternoon and the hot sun generated a metallic smell from the slowly moving dark waters. The company consisted of several buildings; the office was a simple wooden structure painted white. When they opened the door, they entered a large room with employees busily typing and operating large adding machines behind big desks and counters. Seeing the two new arrivals, a young man hurried over with an outstretched hand.

“Hi, I'm Charlie Bischoff. Remember me? The guy that hired you two!” Even in these industrial surroundings, he was the consummate salesman who had so impressed the two young men. He was well dressed, with a tie and high collar. He also sported a striped blazer and a ring bearing the Princeton seal, class of 1916

“Welcome to Fort Pitt,” he said. “Let me show you around.”

Rowe and Lindsay were assigned to desks in a small chemistry lab in the rear of the enameling building, behind hot molten tubs of zinc. This was where the enamel was heated preparatory to being coated on sheet steel in a continuous process. It was very warm and the noise was intense. They stowed their bags under their desks, rolled up their sleeves, and began to explore the new equipment. Rowe noted that the large blowers that brought in fresh air and removed the fumes from the laboratories at Swarthmore were absent here. Open windows had to suffice.

Rowe was hired as a chemist and would be exploring fresh surroundings far from Glyndon. He would also hope to be learning about how the subjects he had learned in class were actually applied in a real business. But within a month, the company's fortunes took an abrupt turn for the worse. The factory workforce went on strike. Financing from the bank ceased, putting the company near bankruptcy. With production shut down, Rowe and Lindsay's jobs disappeared. They were soon on the train heading east.

Rowe had just learned some important, if costly, lessons that would stand him in good stead when he ultimately began to invest in companies for himself, and later for clients. He experienced first‐hand how important strong finances are, particularly when business conditions suddenly change for the worse. He learned about the importance of good labor relations. He learned about the danger of working for a small company without a proprietary product in a competitive industry. Finally, he had been convinced to take the job based on a very good sales pitch delivered by a master salesman. He had not done the research to find out the facts for himself.

Mr. Price was employed here for his first job as a chemist after graduation from Swarthmore.

Rowe's next job was as an industrial chemist at the DuPont plant in Arlington, New Jersey, which produced plastic products. Even then, DuPont was a large company. With a thousand employees, the Arlington plant was much bigger than the close‐knit group of twenty‐eight at Fort Pitt. DuPont was known for its research and development of new innovative chemical products. It appeared to be an ideal place to work for a young chemist just getting started, perhaps a bit like going to work for IBM as a young computer scientist in the 1960s or for Google as a software engineer in the 2000s. The company also enjoyed a very healthy balance sheet. Its labor relations were excellent.

Located beside the marshy Passaic River, Arlington had a population of about two thousand. There was not much for a young man of twenty‐two to do after work in the 1920s. Rowe said later that it was at DuPont that he began to read financial publications such as the Wall Street Journal and Barron's. He found that he was more drawn to them than he was to the latest news concerning new chemical products and processes in thick technical chemical journals. Such financial news media exposed him to a whole new world. He became fascinated by how companies were built, the new products that could form large businesses, and how all of that was financed in the stock and bond markets.

These publications would also have alerted him to the fact that all was not well in the financial and business world. The stock market began to fall sharply in 1921, reflecting deteriorating business conditions – particularly in financially leveraged industries like automotive and real estate. Even the mighty DuPont found itself embarrassed financially in the downturn as its profits nosedived. Pierre S. du Pont, the company's president, had bought a personal stock position in General Motors in 1914. GM was being built at that time primarily from acquisitions engineered by the charismatic William C. Durant, into the largest automaker in the U.S. Pierre du Pont was invited on the General Motors board in 1915.

After World War I, John Jakob Raskob, DuPont's treasurer, convinced the DuPont board to invest $25 million of the company's capital into General Motors stock. This was based on the significant opportunity for profits that he saw from General Motors' leading position in the exploding automobile market. The investment would also help cement DuPont's position as a major supplier of plastic products and paint, not only to General Motors, but to the auto industry as a whole.

For several years, General Motors and its stock did prosper. DuPont became its dominant paint supplier and also developed a number of plastic products for the auto industry. By 1920, General Motors accounted for 50 percent of DuPont's earnings.

Unfortunately, things began to unravel during the short recession of 1920–21. Industrial production declined 30 percent, the stock market fell by almost half, and automobile sales as a whole dropped 60 percent. The General Motors Corporation plunged into a deep loss. Durant, although a visionary with the persuasive power to have put together a General Motors, could not run the resulting conglomerate. In 1920, in a radical move, Durant resigned as CEO of General Motors and Pierre du Pont became president. His brother, Irénée, succeeded him as the president of DuPont.

As a relatively inexperienced chemist who was among the last to arrive at DuPont, it was not surprising that Rowe was laid off in these trying conditions. He spent the summer of 1921 back home in Glyndon. It was a time to reflect on his short, traumatic business career. In two years, two very different companies had employed him. In both cases, he had been laid off. The first time was due to financial problems following labor issues; the second time was due to a sharp decline in business as a result of a recession.

More fundamentally, Rowe discovered that while his interest and enthusiasm for a career in chemistry had waned, growing businesses and the people who ran them fascinated him. He had also discovered the world of finance, particularly the stock market. It seemed to him that it might be possible here to make a reasonable living and, at the same time, to enjoy what he was doing. This was a heady discovery for a young man in his twenties who had been pursuing a profession simply out of the necessity to earn a living.

However, there were no stockbrokers in the immediate family, and at that time stockbrokers were commonly looked upon with some suspicion by businessmen and professionals. Real estate, his grandfather's major asset and business, was a tangible asset that one could touch and see. But even his grandfather might not have supported a move into the stock brokerage business. Real estate increased in price because of supply and demand, which was easy to understand. Investing in stocks seemed to many then – and does still today – to be more like gambling, with stock prices moving up and down for mysterious, emotional reasons. For most people, there was nothing tangible about a stock. Few had an understanding of the actual worth of the companies that these stocks represented.

Years after Mr. Price's death, Steve Jobs, the principal founder of Apple, which today is among the most valuable companies in the world, would tell the Stanford graduating class of 2005: “The only way to do great work is to love what you do. If you haven't found it yet, keep looking. Don't settle. As with all matters of the heart, you'll know when you find it.” Rowe believed, despite the probable misgivings of his family, that he had found it.