18,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Fachliteratur

- Sprache: Englisch

A fascinating set of Black perspectives on what it takes to succeed today In this updated and revised edition of Take a Lesson: Today'sBlack Achievers on How They Made It and What They Learned Along the Way, award-winning journalist and author Caroline Clarke once again compels a dynamic list of Black business heroes and role models to openly share their own goals, hits, and misses, exploring what they overcame and what they're still working to overcome, not just for themselves, but for their peers and would be peers, who the equity odds are still against. In this book, you'll find: * Updated interviews with Black corporate titans containing critically important lessons about business success * Deeply personal accounts of the journeys of Black superachievers from a diverse set of backgrounds and industries who are still rising in their industries * Insights into the ways the world has changed--and the ways it hasn't--since the release of the first edition in 2001 Perfect for Black students and early-career professionals looking for proven ways to navigate the unique challenges they'll face, Take a Lesson is also a great resource for allies seeking to gain perspective on a critically important set of experiences.While these stories are specifically of Black success, their ability to inform, inspire, and reaffirm the value of ambition and perseverance, no matter the odds or era, transcends race.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 334

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Introduction

1 Peggy Alford

2 Keisha Lance Bottoms

3 Samuel Bright

4 Laphonza Butler

5 Veronica Chambers

6 Kenneth I. Chenault

7 Arnold Donald

8 Thasunda Brown Duckett

9 Charles Harbison

10 Carole Hopson

11 Charles “Chaz” Howard

12 Tom Jones

13 Debra Lee

14 Malcolm Lee

15 Alprentice McCutchen

16 Janai Nelson

17 Richard Parsons

18 Kahina Van Dyke

19 Jason White

Acknowledgments

Index

End User License Agreement

Guide

Cover Page

Table of Contents

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Introduction

Begin Reading

Acknowledgments

Index

End User License Agreement

Pages

iii

iv

v

xi

xii

xiii

xiv

xv

xvi

xvii

xviii

1

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

15

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

29

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

53

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

65

67

68

69

70

71

73

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

87

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

107

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

157

159

160

161

162

163

164

165

166

167

168

169

171

172

173

174

175

176

177

178

179

180

181

183

184

185

186

187

188

189

190

191

192

193

194

195

197

198

199

200

201

202

203

205

207

208

209

210

211

212

213

214

215

216

217

219

221

222

223

224

225

226

227

228

229

230

231

232

233

234

235

236

237

238

239

240

241

242

243

244

245

246

247

248

249

250

251

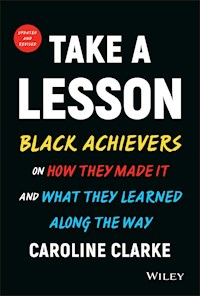

TAKE A LESSON

BLACK ACHIEVERS ON HOW THEY MADE IT AND WHAT THEY LEARNED ALONG THE WAY

CAROLINE CLARKE

Copyright © 2022 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved.

Published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey.

Published simultaneously in Canada.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per‐copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750‐8400, fax (978) 646‐8600, or on the Web at www.copyright.com. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, (201) 748‐6011, fax (201) 748‐6008, or online at http://www.wiley.com/go/permissions.

Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and authors have used their best efforts in preparing this work, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this work and specifically disclaim all warranties, including without limitation any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. No warranty may be created or extended by sales representatives, written sales materials or promotional statements for this work. The fact that an organization, website, or product is referred to in this work as a citation and/or potential source of further information does not mean that the publisher and authors endorse the information or services the organization, website, or product may provide or recommendations it may make. This work is sold with the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering professional services. The advice and strategies contained herein may not be suitable for your situation. You should consult with a specialist where appropriate. Further, readers should be aware that websites listed in this work may have changed or disappeared between when this work was written and when it is read. Neither the publisher nor authors shall be liable for any loss of profit or any other commercial damages, including but not limited to special, incidental, consequential, or other damages.

For general information on our other products and services or for technical support, please contact our Customer Care Department within the United States at (800) 762‐2974, outside the United States at (317) 572‐3993 or fax (317) 572‐4002.

Wiley publishes in a variety of print and electronic formats and by print‐on‐demand. Some material included with standard print versions of this book may not be included in e‐books or in print‐on‐demand. If this book refers to media such as a CD or DVD that is not included in the version you purchased, you may download this material at http://booksupport.wiley.com. For more information about Wiley products, visit www.wiley.com.

Library of Congress Cataloging‐in‐Publication Data is Available:

9781119841074 (hardback)

9781119841098 (ePDF)

9781119841081 (ePub)

Cover Design: Wiley

Author Photo: © Veronica Graves, Courtesy of the Author

Dedicated to you, dear striver, student, dreamer, leader, builder, seeker, explorer, reader. And to your success!

Introduction

For while the tale of how we suffer, and how we are delighted, and how we may triumph is never new, it must always be heard. There isn't any other tale to tell, it's the only light we've got in all this darkness.

—James Baldwin

At the tail end of 2020—the year that wasn't what anyone in the world thought it would be—I did something I wasn't sure I'd ever do: I left my role as chief brand officer at Black Enterprise (BE), the Black‐owned media company where I'd worked for 28 years, to accept a senior executive role in corporate America.

I hadn't sought the new position; it sought me. Having always been a big heed‐the‐Universe type, while it wasn't easy to leave the company and colleagues I'd known and loved, it felt right.

BE had turned 50 in 2020, a milestone that I felt proud to reach with it. Women of Power, the brand I cofounded and ran, celebrated its 15th year at a conference 1,300‐strong in Las Vegas in the earliest days of March. Little did we know it would be the last live gathering any of us would attend for a very long time.

We honored the inimitable sextuple threat (actor‐director‐dancer‐choreographer‐executive producer‐author) Debbie Allen at that event along with pioneering biopharma CEO Myrtle Potter, retired BET CEO Debra Lee, and Nationwide's Chief Administrative Officer Gale King, who, soon after, announced her retirement from the company where she'd spent her entire career.

These women—and the countless people, women and men, I had interviewed during my years at BE—broke molds, shattered ceilings, and obliterated expectations, transforming the places they worked and changing lives with the examples they set. My life was one of those. By sharing their stories with me—on and sometimes off the record—they enabled and empowered me to not only leave BE, but to unexpectedly pivot again months later, when I left my new corporate job to write this book.

It was an unconventional choice, for sure. And a risky one. But the opportunity was unique; I was passionate about the need for this book; and again, the timing—odd as it was in many ways—felt right.

I had reached out to the publisher, John Wiley & Sons, to inquire about my first book, Take a Lesson: Today's Black Achievers on How They Made It & What They Learned Along the Way. It was out of print and a Black publisher was interested in acquiring the rights and rebooting it.

I produced that book, a rare oral history project featuring a cadre of super‐success stories, while heading Black Enterprise's book division. This was back when BE was primarily a magazine, not a full‐blown media company. It was in a time before streaming or smart phones or Twitter, in a land where the idea of there being a Black US president or Black woman vice president or even a Black woman Fortune 500 CEO seemed like a distant dream, at best.

The Black Lives Matter movement was not yet born, and many of the hard‐earned civil rights gains of the mid‐twentieth century were falling away. Yet Black people were still moving, in larger numbers and at a quickening pace, into positions of power and influence in all corners of American life. Black women, in particular, were making critical strides, and I felt blessed and excited to work at a publication where we reveled in chronicling every single one.

Released in early 2001, Take a Lesson sought to illuminate some of those trailblazers in a more prominent and lasting way. It also aimed to fill a gaping need for community among those who were still largely isolated in their organizations and industries, where it was easy to feel that not only they, but their ambitions and hopes, might never actually find a comfortable place to belong.

A series of intimate first‐person interviews with many of the most impressive names from entertainment and finance to education and politics, the book featured the intrepid California Congresswoman Maxine Waters (before she was dubbed “Auntie Maxine” on social media or appointed chair of the powerful House Financial Services Committee); filmmaker Spike Lee (when he was still more Hollywood outcast than insider); and the late lawyer Johnnie Cochran, who successfully defended fallen NFL star O.J. Simpson in the most famous trial of its day.

The original book also included interviews with Kenneth Chenault, who had only just been named CEO of American Express, and his peers Dick Parsons, who was promoted from president of Time Warner to chairman and CEO a few months after publication, and Tom Jones, then chairman and CEO of Citigroup's Global Investment Management and Private Banking Group, who seemed poised to soon join what they all believed was going to be a fast‐growing fraternity of Black corporate chiefs.

They were wrong.

We will, at some point, encounter hurdles to gaining access and entry, moving up and conquering self‐doubt; but on the other side is the capacity to own opportunity and tell our own story.

—Stacey Abrams

Re‐interviewed for this new book 20 years later, all three men, along with retired corporate leader Debra Lee, who not only sits on several major corporate boards but has cofounded The Monarchs Collective, a consultancy dedicated to cultivating board readiness among women and people of color, expressed their deep disappointment and frustration over the lack of progress made in building a truly diverse corporate pipeline or in advancing Black executives who are otherwise succeeding to the top rungs of leadership, including boards. They all also confessed their surprise.

There was a sense of commitment to Black progress and professional advancement at the start of the twenty‐first century that they felt and believed in. Over the next two decades, in spite of a few bright, shining moments, including the election and reelection of President Barack Obama, that sense of broader promise would steadily erode.

The truth is that the systemic racism and hateful otherism in America—that we are only now beginning to squarely confront—rapidly intensified after 9/11, a trend borne out in the determined dismantling of affirmative action; the rise of white insecurity and radicalism within and beyond the Republican party; rampant profiling and more brazen aggression against Black and brown people by law enforcement; the election of Donald Trump as president; and the all‐out assault on African American voting rights that has been shamelessly revived from coast to coast.

As remarkable and instructive as the narratives in the original Take a Lesson were, the significant Black business book audience was neither courted nor calibrated in 2001, and major publishers didn't believe that anyone other than Black readers would have an interest in stories of Black career achievement. Nobody was talking about allies in 2001, or even in 2019. Nobody white was validating the notion put forth by New York Congresswoman Yvette Clarke (no relation to me) that Black history is American history and that the African American quest for success is as valid and vital an experience as there is in all the world.

It's only now, in the wake of George Floyd's murder on May 25, 2020 (preceded and followed by an unending stream of all‐too‐similar race‐based crimes), with the press for antiracism and the trending desirability of wokeness, that Black stories are being sought out and recognized for the value they offer to not only Black people, but to all people who seek to be well educated, informed, and inspired.

So Wiley had no interest in relinquishing the rights to Take a Lesson. In fact, it wanted a new book, representative of a fresh crop of movers and makers along with updated perspectives from some of their predecessors, captured during the complicated but compelling moment in history in which we find ourselves. This is that book.

Actually, I can.

—Meme/classic backtalk

In our spoken‐word tradition, rooted in African soil, lived history is revered and preserved by being passed from one to another, verbally, with candor and great care, over the course of generations, offering a precious inheritance that compounds over time.

For generations, America has built and pacified itself with stories that demean and discourage us as Black people, that enrage and exhaust us, that magnify our shortcomings and compound our pain, doubt, and fear. But there is a counternarrative to that, a living testimonial, a sort of backtalk—or Blacktalk—that demonstrates how magnificently proficient, persistent, resilient, and triumphant we can be, in spite of all that stands against us and conspires to unravel our dreams.

There remains a deep need for those victory stories, the defiant yes‐we‐can‐yes‐we‐will‐watch‐me‐werk narratives of those who defy the odds, who amass wealth and influence, who fall down and get up only to do it all again—changing hearts, minds, and history along the way.

Among the wise griots of our tribal ancestors, the stories of those who rose were not more or less worthy than the stories of those who did not. Every story told has the potential to teach. Every Black story, like every Black life, matters.

In keeping with that tradition, this book is a collection of first‐person narratives with people highlighted here not merely because of what they achieved or how many obstacles they overcame, but because they were mindful of the lessons they learned and embrace sharing them as an act of service and solidarity, born of love and persistently high hopes for our people, and all humanity.

They represent a broad range of skill sets and talents, ages, interests, and backgrounds. Given that, it's not surprising that they offer very different perspectives on success—what it means, what it looks like, what it costs and gives in return.

They are writers, teachers, and high‐powered lawyers; they are CEOs, activists, and corporate directors; they are filmmakers, entrepreneurs, philanthropists, and ministers. Yet not one of their careers fits neatly within the finite boundaries of a single category or title.

All trailblazers in their own right, a few of this edition's subjects would not be where they are if not for some of those featured in the original Take a Lesson. Malcolm Lee traces his belief in the viability of his dream to become a successful screenwriter and director to his cousin, Spike, who gave him his first job as a production assistant on the film Malcolm X. Janai Nelson, recently elevated to succeed Sherrilyn Ifill at the helm of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, was first hired at the LDF by its then leader Elaine Jones, also featured in the first book. And Thasunda Duckett, president and CEO of TIAA, can trace her history‐making turn as that company's first Black woman leader to Clifton Wharton, TIAA's first Black chairman and CEO, who was also the first African American CEO of a Fortune 500 company, period. Now 95, Wharton sent Duckett a personal note upon hearing of her appointment, news that he said was “just wonderful.”

Speaking in the midst of a pandemic, via video, with this book's subjects mostly still quarantined in their homes, it became clear that COVID‐19 changed more than how we work; it changed how we think and feel about racial progress, the past and the future, and what success means and must mean going forward. Black people have never had the luxury of being measured by their individual achievements alone, no matter how spectacular. The accomplished author Veronica Chambers notes in her chapter that “African Americans are in the business of Hope.” But Hope has never been enough. The imperative to lift as we climb is ever present. Every one of this book's subjects speaks to the notion that the Black quest for success is and must continue to be a boldly inclusive collective effort. Sharing their stories here is a part of that.

While some of them have names you will already know, many will have you wondering why you hadn't heard of them before. All share stories you won't soon forget and impart lessons you will want to process and take to heart, using them to help avoid or ease the rough spots on your own journey, before, hopefully, passing them on.

Never underestimate the power of dreams and the influence of the human spirit. We are all the same in this nation. The potential for greatness lives within each of us.

—Wilma Rudolf, sprinter, first American woman to win three gold medals in a single Olympic Games

1Peggy Alford

Executive Vice President, Global Sales, PayPal

In recent years, the comings and goings on the nation's major corporate boards have garnered almost as many headlines and as much scrutiny as the drafting of athletes for the nation's most beloved major league teams. Most of that heightened interest, especially in the wake of the Black Lives Matter movement, has been sparked by corporate America's broad and deeply entrenched resistance to diversity, especially at the top.

So when Peggy Alford was named to Facebook's board in 2019, it was big news—and for good reason. Not only was she the first Black woman to gain a seat at the table with those who help govern the powerful if ceaselessly embattled Internet services company, Alford is also on the leadership team at PayPal. That heady sphere of influence makes her a bona fide unicorn in Silicon Valley, where everyone seeks such storied status but few other than white men with Ivy League degrees actually attain it.

Blending in was never an option for Alford, who was adopted by white parents as an infant, along with several siblings of various races. So not being white, male, or an engineer trained at Stanford or MIT never fazed her. And while she's eager to leverage her skills and influence to make a difference for the companies and clients she manages, personally making news was never on her laser‐sharp list of goals.

Despite Alford's steady rise in tech over more than a decade, she moved from one groundbreaking success to another largely outside of the spotlight. Using her accountant's training as a springboard, she ran Rent.com (an eBay Inc. company) and was COO of PayPal Asia Pacific before becoming CFO and Head of Operations at Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg's philanthropic fund.

By her own admission, this mother of three (two of whom are under age 10) still struggles in social networking situations. In fact, she once described herself as “unapologetically reserved.” But there's nothing reserved about her ambition or her determination to leave a meaningful mark on the world.

When the news came out about my joining the Facebook board, I honestly wasn't prepared for the headline and all the focus on my being the first Black woman. Of course, I should have been, but it caught me off‐guard, which goes back to my beginnings and who my parents are.

My mother was a professor with a PhD in math and computer science and my father was an electrical engineer. They are white, and they adopted six children and fostered even more, of all races. I found out later in life that my [biological] father was Puerto Rican and my [biological] mother was Black and Italian, but when I was growing up, I didn't know what I was.

I was born the first year that interracial adoption was allowed in Pennsylvania, where I was adopted and, in those early days, you could be [mixed with] anything and white people could adopt you, but if you had Black in you, that wasn't allowed. So, the agency lied to my parents and told them that I was Portuguese and white. But it was very clear that I was at least partially Black and, growing up in the Midwest, people made all kinds of comments about what I was.

In second grade, in one of those dreaded assignments about tracing your family's roots, I remember saying that I wasn't sure what I was, but because all of my classmates indicated they were from somewhere in Europe and I knew my adoptive parents were German, I chose Europe too. The teacher said, “That's not true. You're not from Europe.” She pulled out a map and pointed to Africa. “This is where you're from.”

I went home and asked my parents, “Why is she saying this? How could she even know?” and my parents just said some people don't act nice, don't worry about it.

I still vividly remember being good friends with this girl whose house was near ours. When I rode my bike over there with all the other kids to play, her brothers and her dad told me in front of the others that I wasn't allowed in their house. I played in the backyard by myself until they came back out—and I never told my parents because I knew that they would never let me go there again. It's crazy when I look back on it.

Even though those types of incidents happened over and over, I was never taught that it was about race. I remember feeling sad but not really understanding what was going on. I was very clear that it was about difference. At least at that time, in Middle America, you were either Black or white and there was a very singular view of what that meant. Our family would walk into church and everyone would turn and be like, What the heck is this?

There were two sets of us—the older set of three and, after seven years, three more that are very close in age. Two of the younger set are half Black and half white. I was about 13 when they were starting grade school and I remember talking to my parents about moving to a more diverse area so my siblings wouldn't be “the onlies” at school. I explained to my parents why it was important to be around kids that are like you. I was constantly made fun of because my hair was a mess so I tried to help my sister with her hair and convinced my mother about the importance of that.

I was very careful with my messaging and, to my parents' credit, we moved a lot closer to the city. Even now, with my teams, I'm very careful to say things not to criticize but because I want something to change. My parents had to deal with a lot, having us around, and they did their absolute best. I honestly feel so blessed.

Think about the times we're in and the struggles that a lot of us have assimilating, trying to be who we are and to be seen for our whole selves. While I've had some of those same struggles, I also had a better chance of making it all work because, from my earliest days, I was exposed to different races and lots of white people and I lived in a home and a community where I never felt a sense of total belonging. All my life, people have expressed lots of strong, often critical, opinions about interracial adoption, but the reality is that it prepares you for being able to get along with just about anyone, and to do it even when you're uncomfortable.

My parents always made us feel like we were as beneficial to their experiences as they were to ours. That helped me form this belief that I could do whatever I wanted to do and barriers were just something you needed to overcome. They taught us that there are excellent teachers everywhere and the purpose of college is to get a good job—none of this basket weaving.

So, I took a very pragmatic approach to education and thinking about my career. I ran cross country track in high school and was pretty competitive, so I had an opportunity to go to University of Dayton and get some of it paid for. That was really what drove where I went. My first visit to campus was when I was being dropped off. I remember thinking, Oh my God, what did I just do? I'm literally in the middle of nowhere.

I fell in love with the idea of becoming a criminal defense attorney in seventh grade when I participated in a program where we were able to attend a trial. But in my sophomore year in college, I realized I would not have the financial means to go to law school, so I switched my major to accounting because I had found out that pretty much everyone with an accounting degree could get a job.

College and the few years after were where I finally started to become much more comfortable with who I was, but it was tough. I wish I had become more familiar with Black America earlier. I had gone to a diverse high school but—I mean, my last name was Abkemeier! So the Black Student Union didn't know what to make of me, and at 18 (as if being 18 isn't hard enough), that was hard to navigate.

Freshman year I became close to a girl from Connecticut whose father worked for IBM and theirs was the only Black family in their town. She was also Pentecostal and had never been to a movie, so the other Black students were like, Who is this girl? We became roommates and she had a big impact on my life in terms of shifting the narrative to one where we are who we are and no one can tell us who we need to be.

I started to realize I was on a path to actually being able to build some success for myself. I had a good set of friends and, even though it took many years to get there, I knew what I wanted in a relationship. So, I started to worry a little less about what everybody else thought and was able to focus on building the kind of life I wanted.

There were six large accounting firms. Arthur Andersen was number one at the time, and I had the opportunity through a relationship of my uncle's to interview for a job there. Public accounting is a very up‐or‐out culture. If you're doing well, you get promoted every year and make a little more money, so it's hard to say maybe I should go do something else. I ended up being there for nine years.

I had no understanding of how big my career could be, but I was always focused on continuing to build my skill set so that I could do big things. I started in Arthur Anderson's St. Louis office and felt like it was very limiting for women and people of color back then. I was working my butt off and the conversation was always, “We want to grow your career because we need the organization to be more diverse,” rather than talking about what I was bringing to the table. It got super frustrating.

I was always trying to overcome what I felt were stereotypes being placed on my potential, so I was an auditor, and then did M&A consulting which enabled me to do transactional work and help companies go public. Then I went to work for eBay, which grew out of my consulting and, after about four years, I got the opportunity to be the CFO of Rent.com, a company that eBay had acquired. I went on to run that company as the president and GM for three years. When I returned to finance at PayPal, I also took on some operating roles including co‐running HR for a while. I wanted to understand all the levers it takes to run a company because my aspiration was more on the CEO track than in a particular functional area.

Sales was something that I felt was really important and also a little bit counter to my personality. I still struggle with having to go up to people in work environments and start conversations socially. I've had to practice that and it totally drains me. But to learn how to do that well not only helps in every facet of your life, it truly makes you a better executive.

My reserved personality is grounded in not feeling completely comfortable with myself when I was younger. As you get older, you learn to appreciate who you are and not worry so much about what others think. I also have noticed, through observing other leaders I respect, that there is not one successful personality type. Mark Zuckerberg, as an example, is not somebody who's the center of attention in every room and I think he appreciates the quiet confidence of somebody who is really good at what they do but is not necessarily trying to always be talking.

People appreciate authenticity, so it is really important that you always try to become a better you, not someone else or someone you're not. It's about gaining confidence in what you're good at, letting that show, and building relationships around that. That enables people to tap you for opportunities that you might not even have thought were within the realm of possibility.

That was the case when I first heard from Mark about the CFO role at Chan Zuckerberg Initiative literally two weeks after I had my youngest son. I had no plans to leave PayPal and that's not a time when you want to add a lot of change to your life, anyway. You're happy with things being steady so that you can just survive that particular moment. But then I started to learn what he and his wife, Priscilla, were doing, and I've always wanted to be able to drive change at scale, doing good in the world in a way that is good business.

I assess opportunities based on what is going to add to my learning and development, and am I going to enjoy it. The am I ready question almost always pops up too, and sometimes the answer is, I'm not ready, but I'm going to do it anyway. Fighting imposter syndrome is something that you have to keep cranking at every single day.

As women, we question ourselves too much. I have seen so many situations where the guys are signing up for opportunities that they are not prepared for and they go in with full confidence. We need to learn from that. No one's ever totally ready. If you think about any CEO out there, it was a leap for them to take that position and that is relevant at every single level in a company. Your boss, your boss's boss, even the most powerful leaders struggle with the same thing. And it can help to get to a point where you decide to think, What are they gonna do, fire me? Don't do me any favors!

You also have to have supportive people in your corner that will push you. My husband is much more extroverted than I am, so he's always pushing me to make that phone call or go to that meeting or take that chance. This was really important when I was first approached to be on a [corporate] board because my first thought was, I've got little kids and I have this job and I don't have one more minute in the day for one more thing. But my husband said, “If you've got opportunities, grab them. The timing is never going to be perfect. You're always going to feel like you can't put one more thing on your plate but the last time you thought you couldn't get something done, you got it done. So, just do it.” He was right.

What happens for women, and for Black women specifically, is you don't often have either the relationships or the roadmap to show you what you should expect. We don't necessarily have a plan laid out for us that says, here's what you do when you're going for that regional sales leader position, here's how you should be advocating for yourself, here's financially what it should offer, and here's how to spot a progressive position.

Eventually, you start to realize how to leverage what you offer and to recognize if your value is not being appreciated. That requires listening for opportunities in the office and in the market, even if you're not interested in changing jobs. And don't be afraid, when you're having conversations about your career, to say, I'm an ambitious person, someone who's always thinking about whether my career is progressing the way it should. I would love to continue to grow my career within this company but if it's not going to happen, I am going to consider my broader opportunities. That causes people, if you're delivering the message right, to say, wait a minute, maybe we should think about what your next role is or how we add to your compensation. You should take this approach, even when times are uncertain—maybe, especially then.

This last almost two years has been nothing that any of us could have imagined. The beginning was just chaos. We had a son in second grade, a just‐turned four‐year‐old with a 10‐minute attention span, and a 23‐year‐old who was studying finance in New York and ended up at our house in California trying to do college virtually with these little ones that worship him wanting to be all up in his face. Trying to navigate all of that was crazy. But I will say that not traveling all the time, being able to do board meetings and events virtually, and to have dinner with the family much more often was great. So there was a certain comfort with the chaos and, on a broader scale, I do think there will be parts of this that we will sustain.

In some ways this is our time, as Black women. The conversation around the business case for diversity has gotten a lot clearer. The focus has shifted to building products that are relevant to customers, and why diversity of perspective, experience, and background that reflects the customer that you not only serve today but that you want to serve, is essential.

There still is a problem of having the right sort of awareness of all the rich talent that is out there. There's also an issue of leaning into the tried and true versus giving people that first opportunity. We can always help others, regardless of where we are in our career, but you do get to the point where you are getting opportunities that you can pass on to others, or you have a powerful voice in decision making that can enable people to get opportunities. I'm on two public boards and we're only allowed to be on two. So I find myself building my list of amazing Black women and amazing Black men who are ready for that next opportunity. We need to continue to do that for each other and to position ourselves to be both ready as well as in the conversation so we can infiltrate these pipelines to companies and corporate boards.

When I'm recommending people for boards, I very deliberately ask, If you were hiring a white guy, what qualities would you want? It's great that you want to have a board that looks more like our world, but what are the specific skill sets that you're looking to round out, because I don't know who to recommend if I don't know that. And if you don't know that, then are you actually giving someone a seat where they can make an impact?

The same is true as a relates to progression within a company. Being able to home in on additive skill sets within the goal of diversifying is key to making sure that we're giving people opportunities to be successful. The advice I always give is: Continue to work on yourself, always make sure you're prepared, and don't let anyone ever tell you that you're getting a job because they're filling a [diversity] slot.

Honestly, it doesn't really bother me when I get racism from the white side, because whether it's offensive comments or not getting the opportunities I deserve, I view those people as either insecure—worried about losing something they don't deserve—or just ignorant. I am hurt more by people of color who make assumptions about my life and who I am.

We're all made up of the experiences we have lived and the perspectives we've been exposed to, so I do not purport to understand what every person of color's experience has been. I had a different upbringing than most other Black people and there were probably times when I had it easier than others because of that. But it is hurtful when people make assumptions around whether I've had the experiences to be able to know what it really means to be of color or the perspective to speak on certain issues. If you don't know me, you don't know my experiences or my heart.

This all informs how I lead and how I think about my responsibility to develop each individual on my teams. There are some quirky people in Silicon Valley—quirky and super talented. I have met some of the coolest people after thinking at first, They seem odd but let me just stay open and listen. The best teams are made up of people who can truly bring their best selves to the team. And in order to get the very best out of each person, you have to be open to understanding what makes a person who they are, what motivates them, and what makes them prosper on a team versus not.

It's also how we raise our kids. My husband is Black, my kids look mixed, and I am very deliberate about them knowing that they are Black and they are going to experience certain things because of it. I'm very careful about ensuring that they're not judged or disciplined more harshly in school. But my nine‐year‐old is at that age of really making friends and figuring out who people are, and so I'm also very deliberate about making sure he knows that it's okay to be the different kid or to like something that isn't what everybody else likes.

I want my kids and the people I work with to welcome people in regardless of whether they fit “the mold.” That's something that we can do for each other. That's one of the first lessons in life I learned. That's how we achieve diversity.