28,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

Tapestries were among the most prestigious of art forms, created for the mightiest in the land and valued for centuries. Despite its illustrious history, tapestry weaving is actually a simple technique that requires little equipment or expenditure, and can be done anywhere. Written by a prominent tapestry weaver, this lavishly illustrated book gently leads you through the whole process with detailed diagrams and exciting work by contemporary weavers. It will be useful to the absolute beginner, but experienced weavers will also find new ideas and techniques to tempt and inspire them. The book includes a step-by-step guide to setting up a small frame loom and starting to weave; basic and more advanced techniques, and how to create shapes and textures; advice on taking your work into the third dimension, whether bas relief or fully sculptural; information on the qualities of different materials and how they can be used to create the effects you want; and design ideas for tapestry and how to follow supplied designs. This will be an essential source book for experienced and novice weavers, and is beautifully illustrated with 190 colour illustrations and diagrams.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 299

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

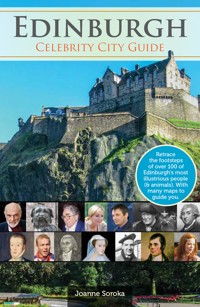

TAPESTRY WEAVING

Design and Technique

JOANNE SOROKA

CROWOOD

First published in 2011 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2015

© Joanne Soroka 2011

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 065 2

Cover illustration: Joanne Soroka, Chaya’s Dream I

Cover photo: Robert George Young

Frontispiece: Joanne Soroka, Scratching the Surface

Back flap: Joanne Soroka in her studio

Graphic design and layout: Margaret Issenman

Photographs

All photographs are copyright of the author, unless otherwise noted. Photographs by the author and Shannon Tofts, Michael Wolchover, Douglas Robertson, Roger Hyam, Sarah Dixon, Brian Fischbacher, Jed Gordon, John McGregor, Norman McBeath, Luke Watson, Mike Griffiths, Sami Yahya, Kim Müller, Jean-René Archambault, Yvan Binet, Michal Kluranek, Maureen Kinnear and Barry Winston.

DEDICATION

For Sandra Brownlee and Maureen Hodge,who taught me to weave,and for Barry.

Joanne Soroka, Eight Canada Geese, 37 × 46in (94 × 117cm).

CONTENTS

Introduction

1

What Is Tapestry?

2

The Origins and History of Tapestry Weaving

3

Getting Started

4

Equipment and Materials

5

More Advanced Techniques

6

How to Create Designs for Tapestry

7

How to Translate Designs into Tapestry

8

Finishing, Showing and Care of Tapestries

9

Inspirational Work from Contemporary Tapestry Weavers

Glossary

Further Information

Acknowledgements

Index

INTRODUCTION

I t is about forty years since I first learned tapestry weaving, but I still remember what a miraculous process it seemed. In this book, I hope to share my enduring enthusiasm for the medium.

Tapestry weaving has an illustrious history. Huge tapestries were owned by the most powerful, who used them to display their wealth and their taste. They were woven by teams of weavers who may have had to spend years working on one enormous piece. These beautiful works of art can now be seen in museums, art galleries and churches. Today, contemporary tapestries are nearly always made by individual weavers who use their own creativity to express themselves through this wonderful medium.

Joanne Soroka, Home, 68 × 56in (173 × 142cm), linen, cotton.

The book is for novices, who may be only vaguely aware of what tapestry weaving is, but also for more skilled weavers who want to expand their knowledge. It is intended as a compendium of information on the techniques, materials and processes, on coping with mistakes and also learning how to create successful designs and translate them into tapestry. Novices will want to work through the stages in an orderly way, but the more experienced can dip into the section that has the information they are seeking, or just be inspired by the range of production of the historical and contemporary weavers.

Diagrams of many of the techniques have been used in preference to photos, since they can be clearer in showing the detail, but in most cases they are supplemented by photos of what the technique looks like when executed. The idea has been to strike a balance between the instructional and the aesthetic.

A special word to those who think they can’t draw. You can. There is creativity in us all and this book provides ideas for ‘drawing without a pencil’. Tapestry weaving may be your path to unlocking the creative force inside yourself.

I came to tapestry weaving through an unorthodox route. I first took a week-long summer course at the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design run by Sandra Brownlee. In Edinburgh, I then went on to two years of evening classes, before enrolling full time with the Tapestry Department of Edinburgh College of Art under the supervision of Maureen Hodge.

Today, most art colleges in the UK are dispensing with skills-based courses, from woodworking to tapestry weaving, and the Edinburgh course is among the many which no longer exist. However, there are still numerous people who would love to learn how to make tapestries. This book is for all of you who may never have had the opportunity to study at an art college and, now that the degree-level courses are gone, it won’t be possible in the future. Tapestry Weaving will guide you gently through the steps so that you can join those who love and practise this ancient art.

1 WHAT IS TAPESTRY?

DEFINING TAPESTRY

Weaving a tapestry is a magical act of melding yarns to create a mural full of power or subtlety. Starting with only limp threads, you can interlace them using colour and texture to create an object that will delight both you and the viewer with the beauty of its surface and its strength or delicacy.

In this chapter, the structure of tapestry will be explained, along with the technical terms you will need to understand how to create your own tapestries. We will also look at the long tradition of tapestry, to show how weavers approached their work, their subject matter and the tools they used to create it.

Joanne Soroka, The Face of the Earth, 1991, 81 × 64in (206 × 163cm), wool, linen, cotton.

Tapestry weaving is a specialized and ancient form of weaving, which like all weaving necessitates a warp, a set of parallel yarns under tension.

Discontinuous wefts, rather than the more common continuous ones of nearly all industrial and other weaving production, are then added at right angles to the warp. Rather than travelling edge to edge, the shorter wefts mean that the tapestry weaver is free to change colour at will and to work on each small section at a time. Tapestry is thus the most versatile, but possibly also the most challenging, of the myriad types of weaving. As the weaving progresses, the warp is completely concealed, hence the term weft-faced fabric, and so the weft creates the imagery as the panel is slowly woven.

The vertical warp is intersected by the discontinuous wefts, which completely cover the warps.

Four examples of different warp settings, from chunky to delicate.

A variety of bobbins.

One of many ways that wefts can be interlocked to avoid slits in the tapestry.

Weaving is based on a grid, with the weft running at right angles to the warp. The warp can be widely or closely spaced, coarse or fine, depending on what you want to achieve. A widely spaced warping will necessitate thicker warp yarns, while closely spaced warps mean thinner ones. The scale of warping also determines the thickness of the weft. A coarse warping can mean a tapestry that includes bold imagery, strong texture and thick wefts and is correspondingly quicker to weave. A fine warping allows detail, delicacy and subtlety, built up more slowly. They each have their merits, with no one setting being superior.

Weaving at its most simple means that a weft thread passes over one warp and under the next, then on the return trip does the opposite. Tapestry weaving is that easy. The demanding part of the task is to make a piece that you enjoy weaving and that a viewer will find attractive, or even thought-provoking and moving.

There are several ways to pick up the warp yarns in order to pass the weft through them, depending on the type of loom and the weaver’s chosen technique. The warp can be manipulated by the weaver’s fingers, or by treadles (the pedals under the loom). Another method is a leashing bar attached to the loom. Leashes, or long loops, are attached to alternate warps. The weaver pulls on the leashes to create a shed, the space between the alternate warps through which the weft passes.

Some people say that tapestry weaving is like darning in its construction. The passing of the weft through the warps is made easier through the use of instruments to carry it and others to beat it into place. Some weavers use a combination of a butterfly, or finger skein (yarn wound around the fingers and secured at its ‘waist’), and a fork or a comb for beating.

Bobbins combine the two functions. These pointed wooden tools have a spindle around which the weft is wound, with the point used to push it into place.

To create each colour area, the weft is woven back and forth in that small area. A slit is created between any two-colour areas, so tapestry is sometimes referred to as slit tapestry. Slits can weaken a finished cloth by allowing sagging or opening up, so they need to be dealt with. Weavers often sew as they go, or else sew them up after the weaving is completed. In other cases, wefts are interlocked as the weaving progresses. There are many methods of interlocking, or dovetailing.

Interlocking is a slower process and can create a fuzzy edge between the two colours. It also means that all parts of the weaving right across the loom must progress up the tapestry at the same rate, while with sewing, the weaver can concentrate on a given area for a sustained period of time.

Tapestries must start at the bottom and build up. Unlike other media, areas have to be woven in a building-blocks order. Each area must support what comes next. If a weaver were to do otherwise, some warps, which have not yet been woven on, would be trapped beneath areas of weaving, making it difficult to access them to work on later.

Materials that have traditionally been used for tapestry weft are wool, silk and metallic threads. The warp was usually wool or linen. Silk might be used for important areas such as faces, and gold threads were used to enhance depictions of fabrics. Today, weavers have a much greater array of materials to use, with warp usually cotton twine or linen, and weft including all the traditional materials, with added ones such as cotton and synthetics. Even paper, strips of cloth, raffia or wire have been used by contemporary weavers.

What Is Not a Tapestry?

The term ‘tapestry’ is often used by commercial manufacturers of kits sold in needlecraft shops or for products such as cushions, but weaving and needlework involve different methods. Embroidery, needlework and needlepoint are sometimes incorrectly called tapestry. These latter techniques involve sewing into an existing fabric, decorating it with stitches of various types. Even more confusingly, one embroidery technique is called tapestry stitch. The Bayeux Tapestry is a famous example of an embroidery generally perceived as a tapestry.

A traditional embroidery from Central Asia known as a suzani, in which a needle has been used to stitch decorative motifs into an existing fabric.

A detail of a tapestry, Cromarty, showing how it looks completely different from embroidery.

Jacquard weaving is also often incorrectly called tapestry. Generally, these are copies of famous historical pieces or sections of them. Upholstery can also be made with this method. The Jacquard loom, the forerunner of early computers, is based on punched cards, and is capable of weaving in great detail. Because it is time-consuming to set up the loom, a given design is made in large numbers. Such panels are sometimes advertised as handmade, presumably because they need a human to run the machine.

Other textile techniques that are similar to tapestry weaving include: looped techniques such as knitting, crochet or macramé; fabric techniques such as quilting or appliqué; dyeing techniques such as batik or tie-dye; and surface decoration techniques such as printing or painting on silk. Rugs can be made in tapestry technique, but are more commonly knotted. Basketry is also close to tapestry, since it is another weaving method, but it is generally made using hard materials. Felting is a process of creating a non-woven fabric, while lace is a group of techniques from knotting to cutting. There are numerous other ways yarns and textiles can be manipulated in an imaginative way. When practitioners use such methods to create works or art, words such as fibre art or wall hangings are sometimes used as all-encompassing for these methods. Off-loom weaving is another term used, although it is not quite accurate, since any weaving needs a loom, even if it is just a simple frame.

When Is a Tapestry Not a Tapestry?

Opinions vary on the topic of what is definitely a tapestry and what is not. For purists, a tapestry is a rectangle made of traditional materials such as wool and linen and is constructed using only tapestry technique. The purest of the pure would add that painterly techniques should not be employed, since that would be imitative of another medium. At the other end of the scale, a tapestry is any textile object that is made by interlacing. Yet others claim that if fibre of any type is included, even in tiny amounts, the piece is a tapestry. Even the definition of ‘fibre’ is at stake, since paper can be considered fibrous and, for example, safety pins can be put together in such a way as to make a cloth of sorts. Debates rage over the middle ground.

Current practice is made up of work by artists in the field, many of whom don’t care about the definitions. They may call themselves textile artists, tapestry artists or weavers, fibre artists or textile makers. While it is safe to say that practitioners will never agree on classifications, there is no real need to restrict one’s own practice based on the ideas of others. Tapestry weaving can be enhanced with the use of varying types of texture; it can be melded with other techniques; it can incorporate diverse and even strange materials; it can be made in sections or move into the third dimension. Experimentation is vital to creativity, and tapestry weavers have explored the gamut of possible techniques and plumbed the depths of their imagination to construct their work.

THE TRADITION OF TAPESTRY

Historically, tapestries of varying sorts have been made in virtually every part of the world, with the strongest continuing tradition occurring in Europe and the Middle East. Weaving is thought to be about 15,000 years old. Then from small beginnings about 3,000 to 4,000 years ago, people began to use weaving not just for blankets or sacks, but to make imagery in cloth. Over the centuries, individuals or teams of weavers produced tiny or huge tapestries, telling stories of battles and coronations, or just crafting decorative patterns.

The Meaning and Use of Tapestries in the Past

European tapestries were made for the aristocracy and were vast, usually narrative works, with the purpose of magnifying the greatness of the owner. They told of his ancestors’ great deeds, his impressive lineage, or his devotion to God. These tapestries warmed the dank walls of his castle and were portable enough to accompany him on progressions through his estates. Their labour-intensive nature and the cost of materials meant that only the richest in the land could afford them, and they were therefore the status symbols of their era, besides being vehicles of propaganda about the importance and power of their owners, or to educate the lower orders and inspire them to turn from sin. Most people would have had few other opportunities to see imagery, especially of this scale and grandeur, and we can assume that they were suitably impressed.

Tapestry Workshops

Since much of the European tapestry weaving tradition comes from France, French words are prominent in the descriptions and technical terms associated with tapestry. Tapestry itself may be called a Gobelin, or Gobelin weaving. The Gobelin family established a dye works in Paris, then added a tapestry workshop in the sixteenth century. The Gobelins manufactury (La Manufacture des Gobelins) has an illustrious history of serving the royal family of France. Today, it creates work primarily for government buildings. Workshops across France, Flanders and Germany supplied most of the production of European tapestry from the fourteenth to the nineteenth century, whether subsidized by wealthy patrons, or commissioned by the richest merchants.

The Gobelins workshops today. The leashes and leashing bars of the high-warp looms, as well as the cartoons, can be seen above the weavers’ heads.

Tapestry Looms

Tapestry may be woven on a high-warp or low-warp loom (haute lisse or basse lisse, vertical or horizontal loom). High-warp looms can be just a wooden or metal frame, sometimes put together like scaffolding. They can be vastly different sizes, but in all cases the weaving is vertical. More elaborate ones have rollers and reeds. Reeds are metal or wooden devices with a comb-like structure for keeping the warps at a correct and even spacing. Each loom would have a range of reeds to accommodate different warp settings. Low-warp looms are similar to or the same as cloth-weaving looms. The weaver bends over the horizontal warp. The warp is unrolled from a roller, passes through a reed and sometimes sets of heddles, and the finished cloth is rolled onto another roller. Heddles are vertical wires with central eye holes, like needles with an eye in the middle, through which each warp thread passes. The treadles are connected to the heddles, allowing the weaver to create the shed by pedalling.

The low-warp loom workshop at the Gobelins. The weaver uses the treadles to change the shed.

Looms range from the simplest wooden frame to elaborate constructions, complete with cross rods (to divide the odd and even warp threads) and other devices. Other apparatus that have helped the weaver include a warping frame for measuring out the lengths of warp and bobbin- or shuttle-winders.

Historically, looms have varied enormously, with some types disappearing from use. In Ancient Greece, for example, the loom consisted of two uprights with a top beam lashed to them. Each warp thread was suspended from the beam and weighted with a pierced stone. The weaver started at the top and wove downward. Another simple loom is the backstrap, where the warp is stretched between the weaver’s body and a convenient tree.

The Tapestry Cartoon

Tapestry weaving in all its guises may have existed for 3,000 to 4,000 years, but it is only within about the last 500 years that painters have become involved in the design aspect. Before that, a design might be made by a prominent artist, but it was only a guideline for the weavers, rather than something set in stone. The weavers were free to make decisions based on the way weaving is structured. Now whether the designer is the same person as the weaver or not, most weavers follow a type of blueprint called a cartoon, a full-sized plan, showing the outlines of each colour area to be woven.

Depending on the tapestry, the colour areas can be easy to separate, but in others the cartoon must show, for example, a range of five colours from orange to red, with the separations marked at exactly the right points. At the Gobelins workshops and some other places, the cartoons are numbered, with each number corresponding to a colour in the palette of wools available. Those who don’t use a numbering system usually rely on a small original design, sometimes called a maquette, to be referred to in conjunction with the cartoon as the tapestry progresses.

Tapestry weavers who use their own cartoons can decide how rigidly they wish to stick to the original design. For some, it is just a general outline, a rough draft, with many of the crucial decisions happening as the weaving progresses. For others, the design has been resolved through much hard work and changes are not contemplated once the weaving is under way, although there are still always decisions to be made about interpretation.

Besides the cartoon, the weaver was additionally helped in following the design by inking the pattern onto the warps. He (and historically workshop weavers were male) accomplished this by pressing the cartoon against the warps and inking marks onto each warp. It would still have been necessary to refer to the cartoon as well, since the huge number of marks on the warps make little sense without it.

The cartoon is the outlines of the major shapes to be woven. The design or maquette, usually at a smaller scale, indicates the colours.

The European tapestry tradition began with weavers having some input into the interpretation of the design, but, over the centuries, the teams of weavers became more and more mere artisans, interpreting rather than creating, with no leeway allowed. It was more a matter of imitating as closely as possible fine gradations of colour, for example the subtle shading of cheekbone and neck. The various weavers on a piece had to minimize differences in style lest a jarring effect between two sections be created.

Cartoons had the advantage of allowing many copies to be made of the same design, with popular ones being rewoven numerous times. Tapestries were often also woven in sets, so that a buyer could have a complete story to hang round a grand reception room.

Workshops around the world still work in this way, with paintings, prints or designs made specifically for tapestry, usually by well-known artists, being the maquettes for designs to be translated into tapestry and woven by the staff. Most contemporary weavers, however, work on their own and combine both roles, designing and weaving their own work.

Weaver Sara Brennan working on a tapestry. The marks of the inking on can be seen in the lower left.

Traditional Tapestry Weaving

Historically, tapestries were finely woven and highly detailed. Weavers of high-warp tapestries sat at the back of the loom, with all the many bobbins hanging down and easily available to pick up as needed. Because they were working in reverse, the cartoon was also a reverse of the design. Weavers had to use a mirror to see the front of the tapestry.

This method of back-to-front weaving was thought to be better because, besides the ease of finding the correct bobbin, the surface of the tapestry would remain neater and cleaner. When looms included a large roller at the bottom, it also meant not having to lean over the work. Today, while some traditional studios still work in this way, most weavers prefer to weave from the front, so as to be in closer contact with the surfaces and textures of their tapestry.

Weaving was also generally done sideways. Tapestries were most often landscape format, so it was more convenient to weave this way, because the looms would not have been wide enough to accommodate the full width. It was also due to tapestries depicting people, trees and other upright figures. Because of the grid that the tapestry is based on, a line that is just off the vertical will look ‘stepped’ if woven as you look at it. This all means that most historical tapestries were woven backwards and sideways, starting from the bottom and working upwards. If it is possible to appreciate their great beauty any more than we already do, we can admire their creators all the more for their magnificent technical virtuosity under these many constraints.

How Long Does it Take?

Because weavers were usually interpreting the design of a famous artist and because those painters made no concessions to the difficulties of interpreting painted marks into wool, weaving the huge tapestries for the courts of Europe was a slow and laborious process. Working long hours, a weaver could complete about 5–10sq ft (0.5–1sq m) in a month, but often much less than that. Today, an experienced weaver can hope to weave up to 1sq ft (0.1sq m) a day, depending on the fineness of the weave, while a workshop will aim for between 2–4sq ft (0.2–0.4sq m) per weaver per week. On the other hand, a fine and detailed piece may mean that only a fraction of these amounts can be accomplished.

HOW IS TAPESTRY PERCEIVED?

We have seen that tapestries were status symbols in Europe and have been highly valued items around the world. Weaving and its associated craft of spinning have also been prominent in the mythologies of many peoples, showing how important these crafts were considered to be. They also have the metaphorical value of suggesting the ‘thread of life’, which may be measured or severed by the Fates. Many stories connect weaving with narrative, unsurprisingly since the Latin for ‘to weave’ is texere, from which we derive the English word ‘text’. Historically, the majority of tapestries have related a tale of some kind and the legends of mythology can weave a story or spin a yarn.

Weaving in Mythology

Myths from traditions as far apart as those of the Ancient Romans and the Navajo tell the stories of goddesses who spin and weave. For example, the Roman goddess Minerva was, among other things, the goddess of weaving. Ovid’s Metamorphoses narrates the fable of a tapestry-weaving contest between her and a mortal woman, Arachne. Arachne was so proud of her expertise that she considered it superior to that of the goddess and sought a competition. After both had completed their tapestries, Minerva could see that she was beaten and was so envious of Arachne’s skill that she condemned Arachne for her hubris by changing her into a spider, to spend the rest of eternity spinning her web.

In the Ancient Greek epic poem, The Odyssey, attributed to Homer, Penelope wove her tapestry as a shroud for her father-in-law as she waited for the return of her husband Odysseus from the Trojan War. Working by day and unravelling it by night, she fended off her many suitors, saying she would accept one of them once the weaving was completed. Her ruse was discovered, but of course Odysseus returned just in time to save her.

In the creation myth of the Navajo people of the south-western United States, Spider Woman, one of the Holy People, taught them skills, including weaving. When a baby girl was born, a spider web would be rubbed onto her hand and arm, so that she would grow up to be strong weaver.

In Chinese and Japanese mythology, a cowherd and a beautiful fairy princess, who was a weaver, married happily, but on Earth she neglected her duty of weaving colourful clouds. When the goddess of Heaven found out, she ordered the princess to return to the skies. The cowherd went in search of her, so the furious goddess scratched a wide river in the sky to keep them apart, forming the Milky Way. The couple sit forlornly on either side, with the princess weaving, only to be allowed to meet once a year on the seventh day of the seventh month, when all the magpies fly up and form a bridge so that the lovers can be together for that one night. The festival is still celebrated with the writing of wishes and poems.

Tapestries in Other Cultures

Because of the time and skill necessary to make tapestries, they are highly valued. Many other cultures have weaving traditions that include tapestries or other textiles made using the tapestry technique. The oldest known tapestries have been found in the tombs of the pharaohs, dating from the fourteenth century BCE. Middle Eastern kelim rugs also use this technique, often called slit tapestry in this case, since the slits are not sewn up.

Detail of a traditional Turkish kelim rug, which has been made using the slit tapestry technique.

In China, kesi or ko’ssu were made entirely of silk and were sometimes used to make the robes of the aristocracy. In South and Central America, sophisticated weavings of different types were being made long before the arrival of the conquistadors in the sixteenth century. Tapestry as the most prestigious of textiles was only for the use of the Inca nobility.

Horizontal looms, often pegged into the ground and highly transportable, were used in the Americas, China, Japan and Egypt. Kelims are usually made on low-warp looms, while other types of rug, especially those made in commercial workshops, can be woven on vertical looms. Weavers who are working for themselves or their families are less likely to be working from a cartoon, but those in workshops will almost certainly be using a pattern.

Art or Craft?

Because of this historical division between the artist and maker, tapestry weaving has often been seen as a craft rather than an art form. There are also other reasons that have been suggested for this perception – mainly that it is associated with the ‘female’ and domestic crafts of cloth weaving, sewing and embroidery. Women were excluded from the world of art until relatively recently. Even the European professional weaver was a man, while the amateur, working in a convent or at home, was a woman. This hierarchical division between professional and amateur, male and female, and art and craft persists to this day, with tapestry being seen by some as lower than painting and sculpture in the hierarchy. Fortunately, these old ideas about relative status are fading away as contemporary tapestry gains prominence.

However, many artists would say that in order for a given work to be art, it must make a statement of some kind, beyond being a decorative object or a representation. It must be trying to make a point. This question of art or craft will be crucial to some, who may struggle to find the way to translate their ideas into a tapestry, and of no interest to others, who wish only to create an attractive piece of weaving.

The Perception of Tapestry Today

While many people are still confused by the term ‘tapestry’, tapestries are widely used in modern architecture and in private settings to enhance their surroundings. They are valued for their ability to warm and soften an otherwise cold and even bleak environment. They can be found in public locations from hotels to company boardrooms. They still have the power to impress, in the same way that they did in the Middle Ages. A weaver may be commissioned to create a tapestry that reflects the type of company whose walls it graces or to commemorate the life of a beloved relative. Tapestries can be seen in locations from hospitals to offices, some of them commissioned specially and others bought ‘off the peg’. Individuals also buy tapestries for their homes, usually but not always at a smaller scale.

Chinese kesi or ko’ssu, a type of silk tapestry weaving, about 1600, with phoenixes and flowers. Photograph © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Joanne Soroka, Edinburgh Castle, a commissioned tapestry in the boardroom of Baillie Gifford and Co., Edinburgh.

WHY WEAVE?

A highly detailed drawing with hundreds of colours can be woven, although it might take years to complete. So there has to be a good reason to translate a particular design into tapestry, given that it is almost always quicker to draw or paint than to weave. What are the advantages of tapestry over other media?

The Advantages

Tapestry weaving has huge potential for creativity and personal expression. An attractive combination of colours and textures, it can be done at any scale, another aspect of its versatility. A large array of materials is available to choose from. The materials are warm and sensuous, with textures from shiny and bright to matte and soft. Contrasts between yarns make for subtle but exciting juxtapositions. Imagery can range from the narrative, through landscape, to the purely abstract. In the past, tapestries generally told stories, whether from the Bible or about a marriage between two great families, with verdure tapestries depicting landscapes. Today, tapestries can make a political statement, depict a pattern on a rockface, or record the words of a poem.

Any image created on paper can be translated into tapestry. As Archie Brennan, a Scottish master weaver, has said:

Tapestry techniques are so developed that virtually anything can be woven. Given proper high standards of draughtsmanship, a skilled weaver can execute in tapestry a Dürer drypoint drawing the equal of a first-class reproduction. It is even possible to construct, in a sculptural woven form, a replica of a Henry Moore stone or bronze figure – not just a recognizable proximity but a replica where form, texture, colour rhythm and tension are properly respected. [2]

While painting and media on paper can be cold and flat, tapestry has a range of textures unavailable to the practitioner in paint. In tapestry, variety is the order of the day. As critic Peter Dormer has said, ‘… the nature of weaving encourages a natural incorporation of diverse materials. Indeed the term ‘weaving’ and the activity it represents are often used as a metaphor for the combining of disparate materials or ideas’. [3]

Tapestry has a sensuality, a softness, qualities which are valued in a world of hard surfaces of glass, concrete and stone. The impact and depth of colour in wool or linen is stronger than that in other media, meaning that a large, vibrant tapestry can be show-stopping.

While opinions vary, tapestry weaving can be considered therapeutic. Some weavers speak of frustration and even sleepless nights worrying about their work, but the rhythm of passing the bobbin back and forth and beating the wool into place over and over again can generate meditative contentment. One is surrounded by soft materials and beautiful colours, with the opportunity to create imagery with personal resonance. The particular tapestry you make has never been done before, so you are creating something new and unique.

The technique is simple to learn and doesn’t require a lot of equipment. Since there is no water, paint or clay involved, it is clean and neat, so an ordinary room space is all that is needed. When you start your first tapestry, you become part of an age-old tradition that goes back thousands of years. There is delight in the finished product. One weaver, Amanda Gizzi, has said, ‘Sometimes I don’t believe I did these pieces!’

References

[1]

Sir Samuel Garth, John Dryden et al., trans, The Works of the English Poets, vol. XX, (London, 1810), Ovid’s Metamorphoses, Book VI, ‘The Transformation of Arachne into a Spider’, trans Mr Croxall, p471.

[2]

Archie Brennan, ‘Transposition of a Painting into Tapestry’, in Master Weavers, Tapestry from the Dovecot Studios (Canongate, 1980), p35.

[3]

Peter Dormer, ‘Textiles and Technology’, in Peter Dormer (ed.), The Culture of Craft, (Manchester University Press, 1997), p169.

Amanda Gizzi, Pickled Peaches.

This Coptic roundel from the eighth century would have originally been attached to a linen tunic. The mounted, haloed figure with a flowing cape is a victorious emperor. Below, a spotted animal attacks an antelope, while a lion turns away. The figures are outlined in a dark colour. Photograph © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

2 THE ORIGINS AND HISTORY OF TAPESTRY WEAVING

While it is not possible to detail the entire history of tapestry weaving in a single chapter, this section will consider its high points to give an overview of its progress down the ages. Focusing on Europe and with the emphasis on more recent achievements, we will chart the development of the medium from its beginnings.