Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Alfredbooks

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

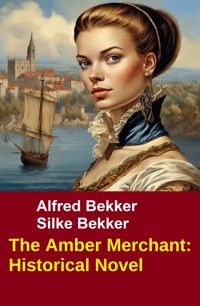

by Alfred Bekker & Silke Bekker The size of this book corresponds to 481 paperback pages. Lübeck 1450: The engagement between Barbara Heusenbrink, the daughter of Riga's amber king Heinrich Heusenbrink, and the rich patrician's son Matthias Isenbrandt is celebrated with a big party. Although Barbara does not love Matthias, she agrees to the marriage of convenience. Shortly afterwards, however, she meets the soldier of fortune Erich von Belden, to whom she feels magically attracted. But they both realize that their love has no chance. And then Barbara is kidnapped to Gdansk by amber smugglers who want to blackmail her father .. .

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 510

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

The Amber Merchant: Historical Novel

Inhaltsverzeichnis

The Amber Merchant: Historical Novel

Copyright

First chapter: Raid on the Curonian Spit

Chapter two: A cold reception

Chapter three: The knight and the poisoner

Chapter four: Lübish intrigues

Chapter Five: The Knight with the Rose Sword Crest

Chapter six: A hanged executioner and three black crosses

Chapter seven: Barbara's engagement

Chapter Eight: Amber smugglers

Chapter nine: On the road to Livonia

Chapter ten: The night of the moon

Chapter eleven: Amber storm

Chapter Twelve: In the castle of the red stones

Chapter thirteen: Ride into no man's land

Chapter fourteen: The man-wolf

Chapter fifteen: The devil in the village of the Danes

Chapter Sixteen: The Amber King of Riga

Chapter seventeen: A rude awakening

Eighteenth chapter: In Riga and away again

Chapter nineteen: Traces

Chapter Twenty: Lots of bad luck

Chapter twenty-first: Journey into the unknown

Twenty-second chapter: Promises kept

Epilogue

The Amber Merchant: Historical Novel

by Alfred Bekker & Silke Bekker

The size of this book corresponds to 481 paperback pages.

Lübeck 1450: The engagement between Barbara Heusenbrink, the daughter of Riga's amber king Heinrich Heusenbrink, and the rich patrician's son Matthias Isenbrandt is celebrated with a big party. Although Barbara does not love Matthias, she agrees to the marriage of convenience. Shortly afterwards, however, she meets the soldier of fortune Erich von Belden, to whom she feels magically attracted. But they both realize that their love has no chance. And then Barbara is kidnapped to Gdansk by amber smugglers who want to blackmail her father .. .

Copyright

A CassiopeiaPress book: CASSIOPEIAPRESS, UKSAK E-Books, Alfred Bekker, Alfred Bekker presents, Casssiopeia-XXX-press, Alfredbooks, Uksak Special Edition, Cassiopeiapress Extra Edition, Cassiopeiapress/AlfredBooks and BEKKERpublishing are imprints of

Alfred Bekker

© by Author

© this issue 2023 by AlfredBekker/CassiopeiaPress, Lengerich/Westphalia

The fictional characters have nothing to do with actual living persons. Similarities between names are coincidental and not intended.

All rights reserved.

www.AlfredBekker.de

Follow on Facebook:

https://www.facebook.com/alfred.bekker.758/

Follow on Twitter:

https://twitter.com/BekkerAlfred

Get the latest news here:

https://alfred-bekker-autor.business.site/

To the publisher's blog!

Stay informed about new releases and background information!

https://cassiopeia.press

Everything to do with fiction!

First chapter: Raid on the Curonian Spit

She may still be very young and, moreover, it is unusual for a woman to be involved in such a business as the amber trade. But no one should underestimate Barbara Heusenbrink. Not for long and she will be in no way inferior to her father, who is not called the Amber King for nothing. Now that Heinrich Heusenbrink is weak and she still has no experience, perhaps the time has come for her to become both father and daughter. Whether with the help of nature or with the support of compliant and armed servants, I don't care.

From a letter attributed to Reichart Luiwinger, the elder of the Rigafahrer brotherhood of Lübeck; unsigned and undated; probably written in early to mid 1450.

The still young and inexperienced Barbara Heusenbrink unexpectedly represented the Heusenbrink trading house on behalf of her father, who was unavailable in Riga and of whom I know through informants that his health was not in the best of health. The Grand Master, however, issued a double warning. He said that it was not yet completely certain whether the previous privileges of the House of Heusenbrink in the amber trade could be guaranteed to the same extent as before, even if he himself was committed to this and confident. And secondly, he advised against taking the overland route to Riga. Although they were under the safe protection of the Order as far as Königsberg, they could only advise against taking the further and currently only overland route via the Curonian Spit to return to Riga by wagon, even if accompanied by horsemen. She should rather accept the waiting time for a ship, because the Spit was unsafe and full of riff-raff and there was no knight of the Order to protect her.

But she said: "As I also took this route on the way here and am now in a great hurry and business obligations do not allow me to wait for a ship, it is better that I take the route over the spit than that I travel over the land of the Lithuanians. I am also accompanied by a number of men-at-arms who are equally loyal to the House of Heusenbrink and extremely knowledgeable in their field. If you really care about me, let us finally come to a final agreement on the trade in the gold of the Baltic!" But she was referring to the amber.

From the minutes of Melarius von Cleiwen, head of the chancellery of the Grand Master of the Teutonic Order at Marienburg Castle; 1450

The flame of a pitch-soaked torch flickered restlessly in the wind that swept across the spit from the sea. The sound of hooves mingled with the sound of the sea and the rustling of the bushes and treetops.

"Now!" a hoarse male voice commanded.

The fuses of the arquebuses were lit - five of them. Within moments, they could be smelled at least twenty paces away - but only downwind. The shooters had carefully positioned themselves so that those they were aiming at remained completely unsuspecting, as the wind carried the smell of the smoldering fuses away from them. Fifty or sixty heartbeats - within this time, the hook rifles had to be fired, otherwise the fuse would burn out and a new piece of rope would have to be attached to the front of the firing hook and made to glow.

The archers waited in the bushes while the team, accompanied by two additional riders, approached at full speed. The two mounted companions were armed. They were mercenaries, the kind you could hire anywhere these days. The man sitting next to the coachman held a crossbow in his hands and looked around restlessly.

The first two shots came thundering out of the pipes. One bullet passed close to the coachman and his guardian and tore a fist-sized hole in the coachman's seat. The second hit one of the two riders. Fatally hit, he fell to the ground and lay motionless while his horse whinnied away.

More shots were fired and just as the second rider had drawn his sword halfway, a bullet went through his leg and then into the body of the horse, which fell to the ground. The scream of the rider who had been hit mingled with the shrill neighing of the horse, which kicked wildly as streams of its blood seeped into the sandy ground, only sparsely covered by sunburnt grass.

A dozen men now rushed out of the bushes, shouting wildly. The injured man lying on the ground raised his sword defensively, while his trouser leg had already turned red. He was still able to parry the sword thrust of one of the attackers, but then an axe blow struck him on the head and ended his life.

The crossbowman on the coachman's seat raised his weapon and cut down one of the attackers before a dagger was thrown into his neck and he slumped to the side, gasping. The coachman sat frozen, pale as a shroud, while some of the attackers had already seized the reins of the team and calmed the horses. Then he jumped off the buckboard, but before he could get back on his feet and flee, he was shot and left whimpering on the ground. The blow with an axe ended his life. Another shot cracked and hit the front wheel, splintering the wood and causing the wagon to sink a little on that side.

Someone was already climbing up the back of the car and using a long knife to cut the cords securing the luggage on the roof.

A man in a stained leather jerkin approached the carriage from the side. He had a hole in his cheek, no doubt made at some point to brand him a criminal. The man so cruelly marked wet his thumb and forefinger with his tongue and extinguished the fuse of his arquebus, for it was no longer likely that he would have to fire the weapon and it was better to save powder and bullets.

He pulled open the carriage door.

"Get out of here! And immediately!"

There was only one person inside the carriage - a young woman who faced the branded man with surprising fearlessness. Sea-green, attentive eyes dominated her finely cut face, framed by dark blonde hair. Her determined look contrasted somewhat with her still very young-looking, soft facial features. She wore her hair up, but the stresses and strains of the journey had tousled it a little, leaving a few strands sticking out. She brushed one of these strands from her forehead with a casual gesture that was both elegant and sober.

The man with the hole in his cheek grabbed her wrist roughly and pulled her out of the car. He grabbed her chin and turned her head to the side.

"That must be her!" said one of the other men - a guy with a dark beard that grew almost to his eyes.

The branded man nodded. His gaze lingered on the amber amulet set in silver that the young woman wore around her neck. He grabbed it and tore it from her neck. Then he held it up to the sun and looked at the engraving on the back. He probably couldn't read it, but he had already seen the H, which had been artistically designed, almost like a miniature coat of arms. "No doubt, she's the woman we're looking for," he realized. "Barbara Heusenbrink - the daughter of the man they call the Amber King in Riga, because every piece of Baltic gold supposedly passes through his hands!"

Barbara Heusenbrink tried to suppress a tremor. She had been warned very strongly not to take the route across the spit, at the end of which a ferry could be used to cross the strait that connected the Curonian Lagoon with the Baltic Sea. But as the land south of the lagoon was ruled by the Lithuanians, the route across the spit was the only way to reach Courland by land without leaving the territory of the Order.

It was obvious that this invited robbers to wait here for prey.

But Barbara had by no means set out from Marienburg a week ago without considering these risks. The well-armed men who accompanied her, loyal to House Heusenbrink, were normally able to put the usual thieving rabble that could be encountered on the way across the spit to flight with ease. It was by no means the first time Barbara had taken this route. She had previously accompanied her father on business trips to the southern part of the Order's territory, to Hanseatic cities such as Danzig, Elbing and Thorn, which were striving for independence from the supremacy of the Crusaders. She had thought she could assess the risk, especially as the usual thieving rabble usually ran away as soon as they noticed that the wagon was accompanied by well-armed mercenaries. Those who lay in wait for easy prey on the spit were usually poorly armed poor dogs who were afraid to engage in a fight. If they had to reckon with resistance, they quickly retreated. Drawing a sword was often enough to drive them away. At the latest, the bang of an arquebus would scare them away and frighten them so badly that you need not expect to encounter the same scoundrels again elsewhere on the same journey.

But the men Barbara had fallen into the hands of on that unlucky day clearly did not belong in this category. Their good armament alone spoke against this and set them apart from the common rabble.

The man with the hole in his cheek looked at the amulet again for a moment and then tucked it under his leather jerkin. He turned to his men. "Get the horses! We should get out of here as quickly as possible..."

"Are you asking for a ransom?" Barbara asked, her voice sounding so sure and firm that the amazement was written all over the face of the man in question.

He grimaced and approached Barbara. "What do you think we're talking about?" he grinned.

Barbara did not avoid his gaze. "You shouldn't speculate on a ransom..."

"As you are the daughter of the Amber King, surely your father would pay any price for you!"

"But you would also pay for it - and very bitterly. For my father would have the power to set heaven and hell in motion to track down your gang and bring you to your punishment. Make do with the luggage and get out. Otherwise you will find your heads on the judgment block sooner than you think possible..."

The marked man's face twisted into a mocking grimace. A scornful remark seemed to be on the tip of his tongue, but then he faltered and turned to the side as a sudden hoofbeat sounded.

A rider came riding across a nearby swell on a white horse. He was dressed like a knight, wearing a doublet, chain mail and an overgarment embroidered with a coat of arms that could be seen from afar. It consisted of a stylized sword surrounded by a rose. The helmet had a few dents.

He carried a rapier at his side, while a heavy two-handed sword was in a leather scabbard attached to the left of the saddle pommel. A reflex bow and a quiver of arrows were attached to the back of the saddle.

"Who could that be?" asked the man who had climbed onto the back of the car.

"Not a crusader, anyway!" growled the marked man and then shouted: "Go on, load your rifles!"

He took a step sideways, raised the barrel of his arquebus and looked over at a large, bulky-looking man in a robe of stained linen who was holding the torch. Anger was reflected in his face when he saw that the torchbearer had already extinguished the fire in the sand and so none of the arquebuses could be made ready to fire quickly in case the stranger had hostile intentions.

"Fool!" the marked man hissed at the torchbearer.

The foreign rider reined in his white horse. He immediately grasped the situation and reached for his bow. Before the crossbowman among the highwaymen could put a new bolt into his weapon, an arrow from the stranger had pierced his neck and he fell to the ground, gasping.

The marked man wanted to pull Barbara with him, but only a moment later an arrow was stuck trembling in his chest, causing him to sink to his knees. He let go of Barbara and she took a step back as the arquebus slipped from his hand. His fingers tightened around the handle of the short rapier on his belt and he pulled the weapon out a hand's breadth before he slumped to the ground and lay motionless.

Within moments, the stranger sent more arrows flying through the air, finding their targets with cruel accuracy.

However, the death of their leader had deprived the gang of all order.

"Come on, get out of here!" one of the men could be heard shouting as he ran off.

The stranger shot his arrows with breathtaking certainty and speed, and almost all of them found their target. It only took a few moments before the marked man's men were either lying dead on the sandy ground, where the grass often struggled to hold on - or they had already fled between the nearby trees and bushes.

The stranger with the rose sword crest finally lowered his weapon and relaxed the string. Then he let the white apple horse trot closer.

Barbara looked after the fugitives for a moment. One of them had an arrow stuck in his shoulder and it was doubtful how far he would get. The rider reined in his horse with his left hand and then got out of the saddle. He kept his bow in his hand and an arrow in his hand. He didn't seem to have much faith in his victory over the highwaymen. In any case, he kept an eye on the bushes behind which the last of them had disappeared. Then his gaze wandered over the dead, who lay scattered on the ground, some in strangely contorted positions.

Meanwhile, Barbara Heusenbrink stared at the knight with the rose sword crest in disbelief. Her heart was pounding wildly and a big lump stuck in her throat. She had recognized the coat of arms from afar - and also its bearer. It had been three years since this knight had entered her life and given it a completely new twist.

And now God's providence had brought them together again at just the right moment. She swallowed and couldn't say anything at first.

"Erich von Belden!" she finally whispered. "That I see you again here and now..."

He indicated a bow. "You seem to me to be in dire straits, and I felt it was my duty as a knight to intervene to protect you."

A restrained smile now played around her full lips for a brief moment. "I have not forgotten how you saved my life three years ago in Lübeck - and now you have come to my aid again in a threatening situation! The Lord must have sent you - both times!"

"I only did what I thought was my duty - but I won't hide the fact that I was particularly happy to do it for you!"

Barbara swallowed. "In any case, I would like to formally thank you for your courageous intervention! Taking on a dozen opponents single-handedly certainly requires more courage than even most of your class!"

Erich von Belden took two steps to the side, bent over the corpse of the marked man and picked up his arquebus from the ground. He held up the weapon and said: "These rifles are a real plague - and the worst thing is that any scoundrel can use them once they've been shown how!" The knight raised his bow. "This, on the other hand, is an art and a good marksman has practiced for years before he can safely hit a wild duck in flight."

"So your art has triumphed over these unchristian weapons!" said Barbara.

The knight nodded and threw the arquebus back to the ground before pulling the arrow from the dead man's body. "Yes, this time," he muttered. "Nobody should actually use a crossbow against a Christian - and yet I've witnessed it happen a hundred times. It would be no different with firearms if they were outlawed in the same way... But who would do that? After all, the Pope has his Castel Sant'Angelo defended by firearms too!"

Their eyes met for a moment and memories came flooding back to Barbara. She involuntarily thought of how she had stood at the window of a patrician house in Lübeck and touched the window glass with her fingertips. It had been so smoothly drawn - clear and so strikingly cleanly set into the frames, as only craftsmen from Venice could achieve. The hustle and bustle that she had observed on the street back then came back to life in her mind's eye. Images, voices, figures, horses, carriages...

A rider had caught her eye - tall, about thirty years old and dressed and armed like a knight. The coat of arms with the rose sword on the tunic had been particularly memorable. At the time, Erich von Belden had had a second horse with him, which had probably served as a pack animal.

A traveler, Barbara had assumed - probably an impoverished son of a nobleman who hired himself out as a mercenary. The flourishing Hanseatic cities - as well as many sovereigns - had an ever-growing need for battle-hardened lansquenets, whom they then took into service.

Their eyes had only met for a fleeting moment.

A little later, she had lost sight of him when he had disappeared around the next street corner. Two paths of fate that would probably not cross again, or so she had thought at first. But only a short time later, he was to meet her again and save her from falling into her doom with her eyes open.

Looking back, the three years that had passed since then seemed like an eternity to Barbara.

Chapter two: A cold reception

[...] I am therefore very pleased that we have been able to reach agreement on the essential points concerning the engagement and subsequent marriage of your son Matthias to our daughter Barbara, as well as the resulting future connection between the trading houses of Isenbrandt from Lübeck and Heusenbrink from Riga. At a time when the free merchant class is exposed to a variety of threats from the almost insatiable hunger for taxes on the part of princes and knights of the order, who, like highwaymen, try to squeeze out the merchants and traders in a completely unchristian way, new ways must be found to stand together against this tribulation under the most adverse circumstances. May this robber barony of rather ungracious sovereigns no longer wrap itself around the necks of honest Hanseatic merchants like a gallows noose! But since the demand for amber, which is not called the gold of the Baltic Sea for nothing, has been unbroken since time immemorial, I see a profitable future ahead of us despite all the difficulties. [...]

From a letter from the Riga merchant Heinrich Heusenbrink - known as "the Amber King" - to the Lübish merchant and councillor Jakob Isenbrandt; written in December 1446; delivered to its recipient not before March 1447:

Lübeck, March 1447 - three years before the raid on the Curonian Spit...

"Shouldn't my future husband be waiting for me at the harbor?"

"Surely he hasn't been informed of our arrival yet, Barbara."

"Our cog has been toiling up the Trave for hours and we've also put a messenger ashore at the north gate to announce us..." She shook her head and gave up the search. There was no one on the shore whose clothing was even remotely befitting. Only dock workers, sailors, salt merchants and begging rabble hoping for the mercy of wealthy passengers. Barbara turned her head, brushed a strand of hair out of her face and looked at her father. "If I can't expect love, I can at least expect courtesy and respect. Don't you think?"

A cold, biting wind blew from the north, blowing into Barbara Heusenbrink's unprotected face as she stood on the aft deck of the "Bernsteinprinzessin" - a bulbous cog of Hanseatic design. Shortly before her departure from Riga, it had been the twentieth anniversary of her birth, which meant that it was high time to enter into a marriage befitting her status, one that would secure the future of the Heusenbrink trading house.

Her attitude betrayed the pride of a patrician's daughter who felt she belonged to a kind of nobility that was not based on birth and the grace of a feudal lord, but on the power of money and the recognition of opportunities to increase it. Her precious cloak underlined this self-confident impression - but even if Barbara had stood on the planks of the "Amber Princess" in her gray penitent's robe and with her head covered in ashes, the pride of a merchant's daughter would have been undeniable - a pride that was not to be confused with arrogance, but was based on a confidence in her own abilities that allowed her to look fearlessly into the future despite all the uncertainty.

Barbara pulled her fur-trimmed cloak tighter around her shoulders as the icy wind cut through the various layers of clothing like a cold knife. She had the feeling that she was standing on unsteady ground - and this was not only true of her stay on the "Amber Princess" with its slippery planks, but seemed to her like a parable of her fate. In any case, she was by no means filled with a feeling of happiness when she thought of her forthcoming engagement to the Lübish patrician's son Matthias Isenbrandt. It was certainly not love that bound them together, but rather family interests, for the moneyed nobility of the merchant class and the traditional nobility were astonishingly similar in their efforts to make politics through marriage. Barbara and Matthias had once met briefly during a party in Riga, which had taken place as part of a joint merchants' conference of patricians from Riga and Lübeck's Riga merchants. A polite greeting and a brief, more or less charming exchange of words - that had been their entire contact to date. To say that they had even known each other superficially would have been an exaggeration. Matthias Isenbrandt looked like a younger, not yet grayed version of his father. His hair was dark blond, his eyes as gray as a hazy autumn day on the coast. He was tall and slim. His clothes, cut according to the latest fashions from Venice or Florence, looked good on him and most of her acquaintances in Riga thought that Barbara had hit the jackpot with him. A husband who was attractive, rich and highly respected in society - what else could a merchant's daughter from Riga expect? Yes, everything seemed perfect on the outside...

Her future life would be decided here in Lübeck. But Barbara had the feeling that the decisive fork in the road was already behind her and that everything that was to come was predetermined. And that frightened her. She had already become painfully aware of this when she had stepped onto the slippery planks of the "Amber Princess" in Riga. And the oppressive feeling she had experienced at that moment had not left her since. The realization that she was on the wrong path, repressed in the furthest corners of her soul, came to the fore with force at certain moments. But there was no turning back, she thought.

A harsh, hoarse call tore Barbara from her thoughts, causing a jolt to pass through her slender, petite figure.

It was one of the sailors whose voice had brought her back to the here and now. He was holding the end of a rope in his hand, had swung himself astride the railing near the bow and was now waiting for the "Amber Princess" to approach the quay wall far enough for him to jump ashore and moor the ship. In the meantime, its sails were taken in. The cog drifted towards a free berth near the Holsten Gate. It was thanks to the influence of the House of Isenbrandt that the "Amber Princess" was able to moor here, in the older harbor area, not far from the salt market. Once you had passed the city wall through the Holsten Gate, it was only a short walk to the merchants' quarter around St. Mary's Church, the town hall and the exchange offices, where coins from all over the world could be exchanged for Lübish marks - provided their gold, silver or copper content was not in any way dubious.

Thanks to the route chosen, the passengers of the "Amber Princess" were spared a long walk through the northern castle gate past the Dominican monastery through a number of narrow alleyways.

The entire crew was now on deck and standing near the railing - including the twenty armed men who had accompanied the ship during the crossing. For a few years now, it had been mandatory for the owner of every merchant cog to have at least twenty men under arms on board. This measure was intended to combat the rampant piracy, which had been attempted for two hundred years, more or less in vain. It had been almost half a century since the notorious Klaus Störtebecker and his Vitalien brothers had met their deserved end in neighboring Hamburg - but many others sailed in their waters and even found sovereigns here and there who gave them shelter or even letters of marque because the Hanseatic League was a thorn in their side.

With a jerk, the "Amber Princess" heeled against the quay wall. The man who had been waiting at the bow now jumped ashore and landed safely. A second man followed and immediately pulled the end of his rope tight, before looping it halfway around one of the spars on the quay wall and mooring the ship, at least for the time being. A halyardreep was lowered in response to a call.

"Now we've reached our destination," said a sonorous male voice close behind Barbara. The young woman half turned and looked into the weather-beaten face of her father, whose eyes had the same sea-green glow as Barbara's. His beard had turned gray and many a wrinkle had appeared on his face. His beard had turned gray and many a wrinkle had already etched itself into his face. Heinrich Heusenbrink was also called the Amber King with a mixture of respect and sheer envy. He bought this Baltic gold from the Knights of the Teutonic Order, who had a monopoly on it in the Baltic countries they ruled. The fact that every piece of amber found on the shores of the Baltic passed through the hands of the Knights of the Order had made them rich and their state extremely powerful. But the Order did not have the necessary trade connections to be able to market the amber itself. Men like Heinrich Heusenbrink saw to this, buying large quantities of amber from the Order at fixed prices, having it polished and then selling it on to his trading partners.

One of the most important of these partners was the Isenbrandt trading house in Lübeck, from where this valuable jewelry found its way all over the known world.

"I have a sinking feeling in my stomach," Barbara confessed. She hadn't felt particularly well when she left the port of Riga, but so far she hadn't let her weakness show and had kept quiet about how she was feeling.

"That comes from the sea voyage," Heinrich Heusenbrink assured us with a smile.

"Yes, maybe..." muttered Barbara. "Maybe it really is just the sea voyage... After all, we've been really shaken up and half frozen to death!" But Barbara knew only too well where this deep unease was really coming from. Everything inside her was resisting what was about to happen, even though she could understand the logical arguments in favor of marrying Matthias Isenbrandt and had initially agreed to her father's plans.

On its own, the Heusenbrink trading company was probably not able to survive. They were still doing well! Heinrich Heusenbrink was still regarded as the amber king of Riga. But all this stood on feet of clay.

Barbara was the only surviving child of Heinrich and Margarete Heusenbrink. This meant that one day she would have to take over the management of the business. Heinrich had done all he could to prepare her for this and she certainly knew more about the amber trade than most of the merchants in Riga and Lübeck. For example, she knew how to estimate the value of the goods on offer with somnambulistic certainty and Heinrich Heusenbrink relied almost entirely on her judgment. The fact that she was a woman did not exactly help her to be taken very seriously among the Hanseatic merchants of Riga, but Barbara was determined to show everyone what she was made of. But Lübeck remained the gateway to the world. And as important as the Heusenbrink trading house might be in Riga, even if it was run by a woman in the future, it was also vital to have a strong partner in Lübeck, from where it was easy to establish trade relations with the entire known world. The Heusenbrinks' trading house would not be able to survive on its own in the long term.

"Let's go ashore," said Heinrich Heusenbrink. Unfortunately, his wife Margarete had had to stay in Riga for health reasons. A lung condition had been bothering her for a long time and she didn't want to put up with the strain of the crossing. If Barbara had been told as a little girl that her mother would not attend her engagement, she would certainly have been very sad. But as she herself had a reserved attitude towards this union, it wasn't so bad. Of course, Barbara would have liked her mother's advice and support, but health came first in this case.

Perhaps I still need to learn to treat what lies ahead of me like a business transaction, she thought. The only catch was that it wasn't about exchanging amber for the highest possible amount in Lübish marks, but that she herself was the object of the exchange.

Barbara and her father stepped onto the bank via the fallreep. Between the banks of the Trave and the city wall was a strip about thirty paces wide, where the goods were handled as they were unloaded from the ships.

Barbara was glad to have solid ground under her feet again. She looked directly at the Holsten Gate. Countless beggars and day laborers had already gathered at the quay wall to earn something while unloading - or, if this was not possible, at least to beg for a pittance. The eyes of these people, dressed in rags of stained linen, were transfixed on the Heusenbrinks and followed their every move. They still kept their distance, because they knew that they could not help their luck by being pushy.

Two carriages approached the berth of the "Amber Princess" and the crowd immediately formed an alley, even before the coachmen rather imperiously asked them to give way to the ship.

The first carriage was intended for the transportation of passengers, the second was probably intended to carry luggage.

A man in simple but distinguished clothing stepped out of the first carriage. He stepped in front of Barbara and her father, took off his cap adorned with a pheasant feather and bowed low. "I am Thomas Bartelsen, clerk and secretary to the honorable alderman Jakob Isenbrandt," he introduced himself. "And if I'm not mistaken, you are Mr. Heinrich Heusenbrink and his daughter Barbara."

"That's right," nodded Heinrich.

Thomas Bartelsen made a special bow to Barbara, greeted her with all the courtesy he could muster and then said: "News of your beauty and your business acumen has traveled ahead of you and reached Lübeck."

"Whoever reported something like that wanted to flatter," Barbara replied with a restrained smile. Such compliments were not really to her taste.

"... and yet he didn't exaggerate at all!" Thomas Bartelsen added to her remark. "Your future husband is certainly to be envied for his good taste in choosing his bride!"

Except that this could hardly have been his own choice, Barbara thought, but kept this reply to herself. However, she wondered more and more why Matthias had not done her the honor personally and gone to the harbor, but had left the greeting of his future bride to a servant. It was not a sign of respect and, with a little ill will, could even be seen as an affront. Barbara was realistic and did not expect any whispers of love or even any false flattery from the man she did not know.

But he could have maintained the forms of decency and politeness, she thought.

At least she would have expected the respect that Matthias Isenbrandt would certainly have shown to an important business partner who had arrived in the port of Lübeck with a cargo of amber, silk or English cloth - for what more important business had there ever been between the Heusenbrinks and the Isenbrandts?

Thomas turned to Heinrich. "I have been instructed to take you and your daughter to House Isenbrandt," he explained. "Everything has been taken care of. You may feel at home in the time before the engagement party and you shall want for nothing!"

"Thank you," Heinrich replied.

"Your luggage will be taken care of, of course. You don't need to worry about anything. The rooms in the Isenbrandt house have already been prepared for you."

Heinrich wanted to give the beggars a few alms, but the Isenbrandt scribe stopped him. "Our people will take care of that," said Thomas Bartelsen, "and as I assume you have come with a lot of luggage, many of these poor people will have the opportunity to earn a few coins."

"And what about the cripples who aren't able to do that?" Barbara intervened.

The clerk's smile at Isenbrandt suddenly seemed very cool. So that's your less gallant face, Mr. Bartelsen, Barbara thought.

"God punished them - why should we reward them?" asked Bartelsen.

A little later, Barbara and Heinrich Heusenbrink drove through the Holsten Gate in the open car in which Thomas Bartelsen had arrived.

The coachman drove the horses forward. The armed guards of the city watch, who had taken up position there, simply waved him through. To the south, the cathedral towered over the houses of the city. Just fifty paces beyond the gate, the merchants' quarter began - clearly recognizable by the magnificent patrician houses that reflected the wealth of Lübeck and its citizens. A babble of voices in at least half a dozen languages filled the streets. Hanseatic Low German, usually called Düdesch, which had become the lingua franca of the Baltic region and was widely understood as far as Scandinavia and the Baltic, dominated, but English, Russian and Polish were also heard - even Italian from time to time.

Merchants were on their way to one of the markets with their carts and jugglers performed their tricks on the street corners and squares. With their colorful robes, they formed a stark contrast to the gray robes of the monks of St. John's Monastery. The monastery district was located on the eastern side of the city on the banks of the Wakenitz, a dammed-up tributary of the Trave that had swollen to the width of the lake. The monastery district was separated from the merchants' quarter by the residential areas of the craftsmen, but they could be found everywhere in the city. Both there, where the magnificent buildings of the patricians dominated the scene, and in the narrow, confusing alleyways where the families of day laborers, shipyard workers or sailors lived. In addition to the St. John monks, there was also a Dominican monastery in the north of the city, whose monks were among the first Christian settlers after Lübeck was founded on the ruins of a devastated Slavic settlement.

The carriage stopped in front of one of the large patrician houses. Thomas Bartelsen helped Barbara off the carriage.

Barbara gathered up her heavy skirts. She was still a little cold. Although she was used to completely different temperatures at this time of year in Riga when the icy east wind blew, the air was drier there. Here, on the other hand, the cold, damp wind gradually made all her clothes clammy.

"Now follow me and let the gentlemen of the house welcome you," said Bartelsen.

Together with her father Heinrich, Barbara climbed the five steps to the main entrance, the hem of her dress rustling on the cold stone. She gathered it up a little and when she reached the fourth step, the double-leaf door was already being opened by the house staff.

Barbara and Heinrich walked into a high-ceilinged reception room. Paintings hung on the walls that tried to imitate the lightness of Italian masters.

A wide open staircase led to the upper floor.

A servant stood ready to take the guests' coats, while at the same time a tall, gray-haired man with hawkish eyes strode down the stairs. This was Jakob Isenbrandt, whose penetrating gaze gave Barbara a brief appraisal and then met her with a cautious smile. Actually, Barbara knew Jakob Isenbrandt far better than her future fiancé, because whenever Jakob had negotiated business deals with the Amber King in Riga, she had always been there in recent years to learn how to conduct such a trade.

At Jacob's side walked his wife Adelheid. She came from a merchant family in Cologne and was said to have an imperious temperament.

Jacob's greeting was friendly and businesslike, just as Barbara knew it from other meetings with him. He even found a few friendly words - in contrast to his otherwise sober and brittle manner - by saying: "My son is certainly to be congratulated on his choice!" He deliberately ignored the fact that it was ultimately not his son's choice at all, but rather his own. "No doubt you will bring new splendor to our house, Barbara."

"Thank you," Barbara replied, bowing her head slightly. "I was very cold on board our cog, but I'm sure your hospitality will soon warm me up."

Adelheid Isenbrandt, on the other hand, did not even attempt to start a polite conversation. As most of the merchant families in Riga were descended from emigrants from Lübeck and there were many family ties between the two Hanseatic cities, Barbara had always heard something about Adelheid Isenbrandt. She was considered cold, calculating and extremely scheming. Some said that she had not always been like this, but that only a hard fate had made her so hard herself. She had borne her husband eight children, three of whom had died in infancy. One daughter had died in agony at the age of 14 from an inflammation of the lower abdomen and another daughter had died in childbirth shortly after becoming the wife of an important trading partner in Bruges. A son named Giselher, on whom Jakob Isenbrandt had pinned great hopes, had gone down in a storm with a cog off Flanders. And just last year, his daughter Adelheid-Marie, who had been very sickly from the start, had died. A fever had caused her to fall asleep without the highly respected doctors entrusted by the Isenbrandts with her treatment being able to do anything.

Some said that this succession of strokes of fate had changed Adelheid over the years, as she had supposedly once come to the Isenbrandts' house in Lübeck at the age of sixteen as a charming and fun-loving person. But this young girl from Cologne probably only existed in the stories of those who had known her back then.

Even in distant Riga, stories had long circulated about the condescending way in which she treated not only servants, but sometimes also one or other of her husband's business partners. Some had made fun of the icy, penetrating gaze with which Adelheid used to scrutinize people when the opportunity arose - but probably only because they were far enough away from the source of this evil and believed themselves to be beyond her influence!

Now this gaze rested on Barbara and the icy wind that the young woman had felt outside no longer seemed so bad in comparison to Adelheid's cold condescension.

Adelheid Isenbrandt's face was elegantly pale. Even though her family's immense wealth was based on maritime trade, she herself had never set foot on a ship in her entire life. The gray-blue eyes looked steely and Barbara shuddered involuntarily at the sight. It was a gaze that gave the impression that it saw everything, penetrated everything and that nothing could remain hidden from it - not even the most secret thought or the slightest emotion.

As unforgettable as this look might be for anyone who was struck by it for the first time, the eyebrows were inconspicuous in comparison. They were white-blond like the hair on her head and therefore barely visible. As Adelheid's hairline was shaved almost to the middle of her head in keeping with fashion, this gave the impression of a very high forehead, which was obviously intentional.

"So this is what you look like," she said, lifting her chin. Her words sounded like a verdict pronounced by a court that allowed no defense. In the blink of an eye, this verdict had been passed with a cold precision reminiscent of the stroke of an executioner's sword. Weighed and found to be too light, that was the verdict. The fact that Adelheid Isenbrandt even refused to address her future daughter-in-law politely was the least of it. On the other hand, Barbara could not possibly imagine that the decision about the impending union between the houses of Isenbrandt and Heusenbrink had been made without the consent of this powerful woman. Adelheid had largely kept out of her husband's business, if the stories circulating among the Hanseatic merchants were to be believed, but it was inconceivable that she had had no influence whatsoever on a decision that was so important for the whole family.

Adelheid turned to her husband Jakob. The height of the lady of the house's chin did not change one iota. "You must know," she said. Then she turned to Heinrich Heusenbrink and continued: "But at least she undoubtedly comes from a good family, even if rumors of financial difficulties have been doing the rounds recently." She shrugged her shoulders after this deliberate act of malice. "But I'm sure those are just rumors..." she added, smiling coolly.

Chapter three: The knight and the poisoner

But nothing should be concealed about the terrible deeds of this woman, even if this should cast a shadow on citizens of the highest standing. For how could justice be upheld on earth if all the filth of sin were swept under one of those beautiful carpets that are made in the Orient and have recently been tried to be imitated in England?

From the written draft of a council speech by Richard Kührsen, elder of the Schonenfahrer brotherhood from 1435 to 1459; undated

"You bring your own weapons - that's good," said Hagen von Dorpen, the commander of Lübeck's city guard, after inspecting not only the foreign knight with the rose-sword crest, but also his belongings, which were stowed on his warhorse and a packhorse. Hagen pulled the two-handed sword from the saddle scabbard and examined the blade.

"Good Solingen steel," said Erich von Belden. "Hasn't rusted a bit yet."

"And your rapier?"

The knight pulled out the blade. It was thin and double-edged - but the most important feature was the perforation in the middle, which saved weight and made the weapon very light and maneuverable. It had not been long since the blacksmiths had been able to produce such a blade that did not become brittle or lose elasticity despite its perforation.

"Do you also want to see how I know how to use the reflex bow? I'll shoot you an apple from the church spire. Let me take on ten of these incompetents who have learned how to use an arquebus or a crossbow in a week! Before these disreputables managed to load their weapons, I'd have struck them all down if I had enough arrows in my quiver!"

"Show me your art later, and if you have lied, you can always be given an easier-to-use weapon from the city's armory!" Hagen von Dorpen laughed to himself and Erich von Belden was annoyed at not being given the opportunity to demonstrate his skills for the time being, as he had the impression that the commander of the Lübish city guard regarded his words more as boasting.

"As you say," said the knight of Belden and gave in, for he needed money and was therefore in urgent need of the expected pay.

Hagen von Dorpen nodded approvingly as his fingers glided over the glued wood of the Hungarian-style reflex bow attached to the back of the saddle. "A good piece! Believe me, I can judge it - even if I prefer the English longbows!"

"For the foot soldiers! Not for riders!" Erich pointed out.

"You may well be right! In any case, you are well equipped so that the city treasury would not have to pay for your weapons when you are employed!" the commander agreed. He pointed to the rapier again. "The coat of arms engraving on the pommel doesn't match the one embroidered on your tunic!" he noted.

"I won the rapier in a tournament," Erich explained. "If you suspect me of being a highwayman, then..."

"Not at all! But your work here will be less glamorous."

"I know that."

"What was the name again?"

"Erich von Belden."

"I'm sorry, but I've never heard of your gender..."

"Our ancestral lands are far to the south. In any case, they are too small to support more than one heir, so I had no choice but to hire myself out elsewhere."

The commander nodded. There were many knights' sons who were in a similar situation. If they weren't the heirs of the castle, they had no choice but to either hire themselves out as mercenaries or join one of the knightly orders.

Erich von Belden had shown the city commander some documents with recommendations, with which he could prove in which armies he had previously served and which cities had employed him as a mercenary and at what rank. But Hagen von Dorpen had hardly looked at these documents and had been told about Erich's career to date by word of mouth. Erich suspected that the city commander simply couldn't read well enough to make sense of the letters of recommendation. Erich had repeatedly pointed out that he had actually gained plenty of combat experience and had last been employed as a captain in the Bremen city guard before he had moved on - because he wanted to be employed as a captain again in Lübeck.

"And what was it that drew you on?" asked the commander.

"You can see from the documents that it wasn't my employer's dissatisfaction that forced me to leave Bremen. It was simply the desire to seek my fortune elsewhere. And Lübeck seemed to be a promising place for me."

"You're not the only one who thinks so! I assume you know what a captain of the city guard has to do and only need a short briefing!"

"That's right," Erich confirmed.

"Then I will appoint you as captain as requested," said the commander. "With your war experience, you will prove yourself worthy of this post - and you will certainly not be worse off here than in Bremen, as I can promise you. You will receive the usual pay and also a new doublet and a pair of pants every year."

"But I'm only on shore duty," Erich von Belden clarified. "There's no way I'm going to be assigned to one of the ships!"

Hagen von Dorpen was visibly surprised by these clear words. He grinned. He appreciated men who said what they thought straight out. And yet - Hagen von Dorpen had been in his post for ten years and no one had ever been recruited on this condition.

"What do you have against ships, Knight Erich?" laughed the commander.

"I can't swim," explained Erich von Belden.

"You'd be in good company - because the art of swimming is not widely practiced among sailors. Some even downright refuse to master it, as this only prolongs the agony of drowning in the event of an accident!"

Erich von Belden shrugged his broad shoulders. "As I said, I fight on horseback and on foot and with whatever weapons! But not at sea."

"I can reassure you," assured the commander. "The escort crews of the fleet are not recruited by the city guard."

"All right then!"

"So make your mark under the contract, Knight Erich!"

Erich von Belden was shown to his accommodation by a simple guard - a room in a building near the stables. He shared this room with two other mercenaries who were also employed at the rank of captain. Each of them was primarily responsible for assigning the guards to a part of the city and ensuring that they were at their posts and kept their weapons in good working order.

Three days later, he had to take a woman into custody who lived in one of the narrow alleyways in the north-west. She lived there by selling all kinds of miracle tinctures, medicinal herbs and the like. Now she was accused of poisoning after one of her customers confessed to having obtained a poison from her. This customer had grown tired of his wife and had therefore inconspicuously mixed the poison into her food. His confession set the ball rolling. A total of nine other cases were now known.

The woman fought back tooth and nail - knowing full well what was about to happen to her. But the two guards who grabbed her and tied her up gave her no chance of escaping her fate.

"I'm an innocent soul!" she cried, screaming like a madwoman as the guards dragged her away.

"As if the devil himself is in her womb and wants to get out!" said one of the men and gave her a rough punch to shut her up. Dazed, her knees buckled and she hung limply in the arms of her guards.

At first, Erich von Belden wanted to intervene, for it was contrary to his chivalric ideals to treat the prisoner like this - even if she was of a lower class. On the other hand, it probably spared her an additional charge of witchcraft if she was silenced in this way and her crazy screams did not echo through the alleys. She was taken outside, her feet dragging on the ground. A team of horses was waiting in the alley to transport the semi-conscious prisoners and the evidence to be confiscated.

Mina Lodarsen was the woman's name. Erich estimated her age to be in her early thirties.

The knight instructed several other beadles in the service of the city to take away all the bottles, jars and other vessels so that the poisoner's guilt could be proven and relatives or accomplices accused of being accomplices did not set about getting rid of everything.

Erich found three frightened children in an adjoining room.

A girl of eleven or twelve and two boys who Erich estimated to be five and nine. They were skinny and their clothes were covered in dirt and they were shivering.

Erich would later learn that the father of these children had been a sailor on the cog of a salvage ship that regularly brought large quantities of stockfish to Lübeck, which was sold from there to Bavaria and Italy. During a storm, the sailor had gone overboard in the Skagerrak and since then Mina had had to fend for her children on her own.

Now they were left to their own devices. No matter what guilt their mother might have brought upon herself - before Mina was even judged, her children had already been cruelly punished.

Inhuman screams rang through the dark cellar vaults. The city executioner and torturer inflicted Mina Lodarsen with red-hot irons and pincers, for she had not responded to the torture instruments with a full confession, but had become entangled in the web of her lies and evasions.

Commander Hagen von Dorpen conducted the interrogation and Erich von Belden was present as a witness. As Erich could write and no other scribe was available at the moment, he was instructed to record the testimony. The executioner clearly seemed to enjoy his craft and couldn't wait to inflict the prisoner again. The smells of blood, sweat, urine and burnt flesh mingled in a way that could almost take your breath away.

Erich hated having to do his duty in this torture cellar. The screams of Mina Lodarsen mingled in his mind with the screams of the wounded and dying on the battlefields where Erich von Belden had fought. A chorus of damned souls that sometimes haunted Erich to sleep and was now probably joined by another voice.

The torturer took the iron once more and left a dark brand on her thigh. Mina Lodarsen squirmed in her bonds. Her cries had become weak and quiet.

"Do you really believe that this approach promotes the truth?" Erich von Belden finally asked.

The executioner grinned. "It won't get in her way either," he said, laughing broadly.

"Not even if this woman is just talking crazy and doesn't even know what she's saying anymore?"

"You seem to have a charitable heart, sir," said the executioner, grinning wryly. "But you shouldn't forget how many murders this sinner has assisted in!" He spat out, expressing his contempt. "Just a quarter of an hour she should be left to the mob out there! The people from her own alley would tear her apart alive, making her wish she was back in my care!" He chuckled.

"Leave it alone!" even Hagen van Dorpen now intervened. The prisoner's will was finally broken and she now quietly confessed the first names.

The executioner seemed pleased that he would probably have enough to do in the future. Erich, on the other hand, suspected that there would probably be dozens of arrests over the next few days. According to her, most of the remedies and tinctures that Mina Lodarsen had made had not been mixed for the purpose of creating the most effective poison mixture possible, but for other reasons. Potions to influence other people in matters of love were allegedly the ones Mina Lodarsen sold most frequently.

Erich von Belden often had to ask her not to speak so quickly, as the knight and newly appointed captain of the city guard was not even close to being able to keep up with the recording of her testimony. In moments like these, Erich wished he hadn't been able to read and write, so that the chalice of such an interrogation would have passed him by. Erich's father, Baron von Belden, had insisted that Erich regularly spent time in a monastery school to learn to read. "If I can't leave all my sons an estate that can support them, then they should at least be solidly trained - with the sword as well as the quill! That will increase the likelihood of finding a livelihood - because, unfortunately, a noble can no longer acquire anything for honor alone in these times!"

These words rang in Erich's ear. Certainly the Baron von Belden had never thought that his son might be forced to work as someone who had to write down the confused ramblings of a tortured poisoner. But a new era had simply dawned in which the old ideals and virtues counted for little. For Erich, writing was the symbol of this new era. Whereas in the past the word of a sovereign lord had been used to dispense justice, now everything was written down. The laws as well as the stammering of a tortured person - just so that there was proof afterwards that the right person had been sentenced to death and executed. It was a time when money began to count for more than honor and knights only had the choice of having their breastplate pierced by the bullet of an unknightly arquebus or the bolt of a crossbow or using such dishonorable weapons with their own hands if they wanted to survive on the battlefield.

Money dominated everything, as Erich had found out time and again, and money was ruled by those whose hands it mainly passed through: merchants. But wealth was something that Erich was completely indifferent to. He only wanted as much as he needed to live on and that was what he got here in Lübeck.

His thoughts wandered while his commander reminded him to write down everything that was relevant.

"Isn't there already enough incriminating evidence?" asked Erich. "They can only be executed once. So basically one single case is enough, and it has to be well documented. The rest can be decided by a higher judge."

"You speak lightly, Erich von Belden," replied Hagen von Dorpen. "Besides, these are thoughts that do not belong to us, but to the court that will pass judgment."

When the interrogation ended, a bent bundle of human misery lay on the cold stone floor of the dungeon, which was inadequately covered by straw. The linen gray, torn shirt that had been left for Mina Lodarsen was stained with dirt and blood. She was still recognizable as the woman who had been arrested that morning.

Hagen von Dorpen and Erich von Belden left the dungeon. The executioner accompanied them. As they stepped outside, Erich was blinded by the sun and a torrent of drooling voices rang out - some of them shrill and distorted.

"Where is she, the poisoners?"

"We want to see them!"

"To hell with the witch!"

"Burn them!"

"She shall suffer - like her victims!"

"An eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth!"

About fifty people had gathered outside. Some men, but mostly women and even some adolescents and children were among them. Their faces resembled hate-filled grimaces. The news of the arrested poisoner had spread like wildfire.

"We will have to act quickly if we want to catch the accomplices and accomplices involved in the crimes," said Hagen.

The crowd pushed towards the door and obviously wanted to gain access. Erich von Belden drew his rapier. "Get out of here!" he shouted in a booming voice and suddenly there was silence. "Go about your business or whatever you have to do! Justice will be done to the poisoner - but the Lord says: 'Let he who is without sin among you cast the first stone. And so I ask, who among you may be without sin?"

The people stared at Erich with wide eyes that showed nothing but blank incomprehension.

Hagen von Dorpen put a hand on Erich's shoulder.

"Put your gun back in its place, Erich!"

At first, Erich thought he had misheard him.

"Do you want to surrender to the lynch mob? You can't possibly be serious!"

"You're new here in Lübeck. That's why I give you credit for not knowing the circumstances..." He turned to the executioner, who was standing somewhat irritated at the door. "No more than ten people at a time, do you understand me, executioner?"

"Yes, sir!"

"And don't be too greedy with your entrance fee! Otherwise this mob will end up lynching you and then the poisoner."

"Yes, sir."

Hagen von Dorpen pulled the astonished Erich along with him. The crowd made way willingly, if only to avoid injuring themselves on the sharp double edge of the rapier that Erich finally sheathed.

"What's going on here?" the knight of Belden finally asked, barely bothering to hide his anger.

"Let me explain it to you, Erich," said Hagen von Dorpen. "The executioner allows people to look at the stigmata he inflicted on the poisoner. In return, he takes a fee from every onlooker. People are keen to have a look - especially in a case like this, because murder by poison is particularly insidious, as I'm sure you'll agree."

Erich shook his head in bewilderment. "You allow such deals? Justice may be harsh at times - but this is unnecessary cruelty," Erich stated.

Hagen von Dorpen laughed hoarsely. "Do you know what's really cruel, Erich? That the executioner has to feed his family on a pittance!"

"And I simply can't imagine that the Lübeck City Council would approve of such deals!" Erich insisted.

"No, he doesn't approve of them either," Hagen von Dorpen admitted. "But he tolerates it, because they are well aware of the fact that the executioner cannot live on his wages and would otherwise have to be paid better."

Erich took a deep breath. He looked around briefly and watched as the executioner collected his fee from the first ten disgustingly drooling onlookers.

"I thought Lübeck was a rich city!" growled Erich.

"The merchants are rich," Hagen corrected him. "The brotherhoods too! But the town itself doesn't even have enough money to finally replace the stained linen cloth in the windows of the town hall with glass!"

About half of those Mina Lodarsen had named under torture were still in custody. Others had left the city - whether because of urgent business or because they were all too aware of their guilt and feared that their own crimes would be revealed after the poisoner's arrest was hard to say.

Of course, most of the prisoners claimed that they had only used the services of Mina Lodarsen to have harmless love potions or a cough medicine made from crushed poppies, the latter of which was said to have the positive side effect of sending pleasant dreams and making you feel less cold in winter. Mina also knew several recipes for baking poppy seeds in bread - either when grain was in short supply or because people appreciated the calming effect of eating these breads.

"I wonder how many of these unfortunates were only named by the poisoner because she was hoping for an end to their pain," said Erich von Belden after one of the interrogations that took place over the next few days. In the meantime, this matter had also been given greater importance by higher authorities. A judge appointed by the council was now present at the interrogations of Mina Lodarsen. He was a gray-haired, narrow-lipped man whose reserved manner had been unsympathetic to Erich from the start. More and more actual or alleged crimes came to light through Mina's statements. An abyss of insidious murderousness and unscrupulousness seemed to open up.

The poisoner was no longer tortured because she was talking like a waterfall. Apparently she had realized that they would let her live as long as there was a chance that she would help to solve further misdeeds. Moreover, it had not yet been decided whether the poisoner's activities should also be classified as a form of black magic. The abbot of Lübeck's Dominican monastery had searched the woman's body for devil's marks, whereupon the executioner and the city commander were sharply reprimanded. After the woman had been so badly maltreated and her body was covered with burn marks and wounds, a proper examination was no longer possible. After all, the intact areas of skin were without findings. What mattered now was what the other accomplices and witnesses had to say about a possible connection between the poisoner and Satan.

Mina Lodarsen, however, reported new murder conspiracies every day, but their descriptions became increasingly contradictory and implausible.