Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: BoD - Books on Demand

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

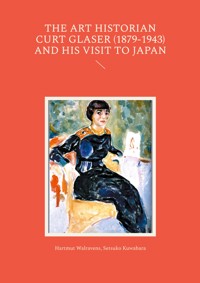

Curt Glaser (1879-1943) was a versatile scholar: he first studied medicine and then, probably at the suggestion of his wife, who was very interested in art, art history, and earned doctorates in both subjects. From 1909, he worked as curator of the Berlin Kupferstichkabinett (Museum of Prints and Drawings) until 1924, when he succeeded Peter Jessen as director of the State Art Library, a position he lost in 1933 due to Nazi racial laws. He foresaw the catastrophe and immediately emigrated to Switzerland and Italy until he arrived in the USA in 1940, where he died in 1943. Glaser turned the art library into a center of Berlin's art life - he organized exhibitions, held regular events in his large official residence (a kind of salon, whose soul was Mrs. Glaser), maintained close contacts with modern artists (he "discovered" Edvard Munch, for example), wrote regular art reviews for newspapers and magazines, was a prolific writer, and was intensely involved with East Asian art, on which he also published. His book on Japanese theater was edited by no less than Otto Kümmel, director of the East Asian Art Department and an art historian of East Asia who was widely feared as a critic. His work on The Representation of Space in Japanese Painting was published as early as 1908. Despite his many activities and achievements, Glaser was quickly forgotten - early emigration and death during the World War before he could put down roots in the USA - contributed to this. It was only the efforts of his heirs to restitute his art collection that brought him brief publicity, not least thanks to an opulent work on Glaser as a collector. This book deals with a hitherto largely neglected facet of Glaser's work, namely his interest in Japanese art, with which Glaser and his wife became familiar during a lengthy trip to Japan in 1911. Since, due to his emigration, hardly any information about this trip has survived from Glaser's side, Dr. Kuwabara has attempted to find more details in Japanese sources and, above all, has translated an essay about Glaser's visit by the Japanese doctor and writer Ôta Masao (1885-1945; pseudonym Kinoshita Mokutarô). In addition to a biographical introduction to Glaser, the volume includes a (by no means complete) list of Glaser's writings (almost 600) and two of his short essays on Japanese theatrical arts.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 161

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

Curt Glaser (1879–1943) – Life and Work

List of Publications

Curt Glaser in Japan

Kinoshita Mokutarō: Viewing the Treasures (Hōmotsu haikan 宝物拝観)

Glaser: The Style of the Japanese Stage

Glaser: On the Forms of the Japanese Theater

Index of Personal Names

Curt Glaser (1879–1943) – life and work

Curt Glaser. Portrait by Max Beckmann, 1929 St. Louis Art Museumhttps://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Portrait_of_Curt_Glaser_8451983_.jpg

Introduction

Despite his many years of versatile activity in Berlin, Curt Glaser is little known today.1 His emigration and death in exile, as well as the loss of many files and archives during the war, make it difficult today to trace his life in an appropriate manner. Since the available material is now available in the form of an excellent biography and appreciation by Andreas Strobl2, only a sketch is given here as an introduction.

Curt Glaser was born in Leipzig on May 29, 1879. His parents were Simon Glaser and Emma Glaser, née Haase. He graduated from a Berlin grammar school (gymnasium) in 1897 and studied medicine and then art history at the universities of Freiburg/Br., Munich and Berlin under Heinrich Wölfflin (1864–1945), whom he greatly admired throughout his life. He completed his medical studies in Munich in 1902 with a doctorate3 and his doctorate in art history in 1907 with a thesis on Hans Holbein4. He seems to have come to art history at the suggestion of his wife, his cousin Elsa Kolker5 – she was a lively woman with many interests, who was regarded as a skillful and elegant hostess in the Berlin art world. She died in 1932 after a long illness. Edvard Munch (1863–1944) who became a good friend of the Glasers painted her portrait.6 He had been curator at the Kupferstichkabinett (Cabinet of Prints) in Berlin since 1909. During the First World War, Glaser served as an army physician. In 1924, he succeeded Peter Jessen (1858–1926)7 as director of the State Art Library, a position he lost in 1933 due to the Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service8. Although he had professed to be a Protestant since 1914, his Jewish origins made it impossible for him to continue working in Germany. In June 1933 he emigrated to Switzerland (Ascona). During extended visits to Florence between 1936 and 1939 he wrote his last major work, Materialien zu einer Kunstgeschichte des Quattrocento in Italien.9 In 1940 he succeeded in emigrating to New York, with his second wife Maria Milch10, and died on November 23, 1943.11 Some of his papers are preserved in the Leo Baeck Institute in New York. Glaser was no stranger to America; shortly before his emigration, he had traveled to the USA and written a travel book for a wider audience.12 Glaser assessed his situation realistically in 1933: The death of his wife, the destruction of his professional livelihood and the political developments left him with only one choice: emigration, and so he had his art collection and library auctioned off as early as May 1933.

Curt Glaser had two brothers: Felix Glaser (born on May 11, 1874 in Leipzig) attended the Falk-Realgymnasium in Berlin, then studied medicine in Strasbourg, Munich, Berlin and Kiel and completed his doctorate under Rudolf Virchow with the thesis: Haben die Muskelprimitivbündel des Herzens eine Hülle? (“Do the primitive cardiac muscle bundles have an envelope?”) He became an assistant to Prof. A. Fränkel and later did scientific research on the autonomous nervous system. His collective reports on this topic appeared in the journal Medizinische Klinik. Since the founding of the Auguste Victoria Hospital in Berlin-Schöneberg (1904), he worked there as the leading physician of the department of internal medicine.13 Felix Glaser died in 1930. His second brother, Paul Glaser, became an art dealer; he emigrated to Brazil, where he died in 1940.

In addition to his museum activities, Curt Glaser was very active as an art writer for many years: he was associated with the magazine Kunst und Künstler and was at times the Berlin editor of the Kunstchronik; he also wrote as an art critic for the Berliner Börsen-Courier. Andreas Strobl identified and listed the many contributions for the first time.14 One recently rediscovered article is:

The new “Jewish Museum”15. Glaser’s position on the new Jewish Museum in Berlin, which had just opened in 1933, is remarkable: in his opinion, a Jewish Museum could only be conceived as a museum of cultural and religious history, because “on the other hand, one must ask the question of where it leads when any still life or landscape by a German painter of Jewish denomination is presented here under the title of Jewish art. It leads to an entirely undesirable and in no way factually justifiable division. [...] There is as little Jewish art outside the cult sphere today as there is Catholic or Protestant art.”

Edvard Munch: Curt and Elsa Glaser 1913 Private collection (as of 2023 on loan to Munchmuseet, Oslo, PE-M-00786)https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Elsa_and_Curt_Glaser.jpg

When Glaser was director of the art library, he lived in the official apartment at Prinz-Albrecht-Str. 8, the same building where the Secret State Police (“Gestapo”) later moved in. Leopold Reidemeister (1900–1987) published two photos of the apartment – the library and the study – in his Erinnerungen an das Berlin der zwanziger Jahre (Memoirs of Berlin in the 1920s)16. Glaser’s portrait by Max Beckmann is clearly recognizable in the library hall. Attendees met at Glaser’s after the lectures in the art library.17

An important part of Glaser’s art collection, about 200 prints, were bought at the Glaser auctions in 1933 by Otto Fischer (1886–194818) for the Basel Kunstmuseum. Negotiations with Glaser’s heirs came to the result that the Museum might keep the prints for a monetary compensation but should publish a volume of appreciation on Curt and Elsa Glaser. This was done, and the catalogue which focuses mainly on the art collection also contains biographical material and photographs – a truly splendid documentation: Der Sammler Curt Glaser: vom Verfechter der Moderne zum Verfolgten, herausgegeben von Anita Haldemann und Judith Rauser.19

A comprehensive appraisal of Glaser’s work is neither intended nor possible here; instead, a field of work in which there were few experts at the time, but many amateurs and collectors, is addressed here: East Asia. The subject was in the air, so to speak; however, Japonisme had largely died down in the meantime and interest in China had grown stronger. As a result, Glaser also became intensively involved with the art of East Asia. His work on The Representation of Space in Japanese Painting was published as early as 190820. It is therefore hardly surprising that a longer journey took him and his wife to Japan in 1911; presumably it was a trip around the world, as was fashionable at the time21 – although Glaser’s journey lasted about a year. Unfortunately, we have no travelogue by Glaser, only a few small articles in the press. Meanwhile, Kinoshita Mokutarō 木下杢太郎 (1885–1945), a doctor and writer, published a short story Hōmotsu haikan 寶物拝觀 in 1915 about Curt and Elsa Glaser’s visit to Japan. Kinoshita, who was still a young doctor in 1911, accompanied the couple as an interpreter when they visited Japanese art treasures and collectors.22 The immediate result of the trip was Die Kunst Ostasiens (1913)23, a stately volume dedicated to Elsa Glaser, which does not aim to be an actual history of art, but rather seeks to outline the scope of East Asian thinking and design.24 Glaser notes in the foreword: “This book is based on the experience of a foreign culture. We are talking about the aesthetic attitude of a people in the broader sense. Not of art alone. That is why the title of the book is too narrow. And it is too broad, because the intention was not to simultaneously describe the entire field of fine art and trace its historical development.

The aim was merely to establish guidelines, to provide visual norms and to show what is legal in the phenomena.

Everyone sees with the eyes of their time. When Japanese art was discovered in France, it was natural that it should be understood in terms of the theory of Impressionism. Today we ourselves seek new paths to form, and we see the lifeblood of East Asian art in the strict adherence to a stylistic will sanctified by unbroken tradition.” (p. VII). Glaser seems to have been particularly impressed by the style and aesthetics of East Asia. He uses the terms of Xie He’s 謝赫 art theory, the “Six Principles 六法”, and dedicates the final chapter of his work to the reception of East Asian art, to the enjoyment of art: “The work of art becomes alive and effective in the person who enjoys it, and at the same time it is given an existence of a higher order, which makes it a being like others created by nature. No hallucination makes the picture seem alive to the beholder, and no God reveals himself in the work of art. Man’s creation enters into the natural context of things and participates in the soulfulness of the universe.” (p. 194) The second monographic contribution to East Asian art is his Ostasiatische Plastik, edited by William Cohn25 in the series Die Kunst des Ostens26, published in 1925 by Bruno Cassirer, who was also interested in East Asian art. The volume is dedicated to Ernst Grosse (1862–1927)27, who was a subtle connoisseur of Japanese art and Otto Kümmel’s28 teacher and inspirer29. This is all the more remarkable as Grosse himself had published a booklet Die Ostasiatische Plastik in 1922 with the Seldwyla publishing house. 30 It can therefore be assumed that Grosse had a positive, or at least not a negative, attitude towards Glaser’s presentation. “The attempt at a coherent presentation of the entire field of East Asian sculpture requires some justification for its boldness, as no one is more aware than the author of how incomplete our knowledge – at least as far as China is concerned – still is,” Glaser admits. He concentrates on a study of the history of sculpture in East Asia, seeking to fill in the gaps in his knowledge of Chinese sculpture with Japanese sculpture. He is aware of the problem, but argues: “Certainly this view goes against a new orthodoxy. For today it is customary to view everything that originates from Japan with a certain degree of contempt, and only the Chinese are considered valid. This fashionable attitude is based on the correct insight that China was actually the creative country of the East. But Japan played a major part in the great artistic flowering that originated there, and the better-preserved monuments of large-scale sculpture from the classical periods in the temples of the island kingdom are the most important documents of a common East Asian art. The author admits that in many cases he is unable to answer the question of whether the creator of this or that work was Chinese, Japanese or Korean by birth and descent.” (p. 1) Glaser later gave an overall account of East Asian art in Springer’17s Handbuch der Kunstgeschichte (6.1929)31.

Worthy of note is a short but substantial, programmatic essay on the tasks and methods of European research in the field of Eastern art, which first appeared as the introduction to the East Asia issue of Cicerone32 and was then reprinted in Biermann’s Jahrbuch der asiatischen Kunst 33 . Glaser poses the legitimate question of what a European scholar could contribute to the study of East Asian art. He warns against uncritically transferring European methods to this area of art, but also against trying to compete with the Japanese, for example. He pleads for a separation of ethnology and art and advocates cooperation with philologists: “The requirement, which is taken for granted within Europe, that the researcher must have a complete command of the language of the country whose art he is studying, has no validity in the Far East, because the requirement as such is impossible to fulfill. With this renunciation, however, the possibility of applying the same working methods to both areas also disappears. The art historian, who is at best only imperfectly able to read the literary source works and the inscriptions, in the interpretation of which professional sinology itself often enough fails, finds himself dependent on the help of external assistants, and it cannot be his ambition to carry out independent work in the study of sources, for example.” (p. 246) Glaser thus outlined his own situation well, but also took into account the views of the most demanding experts of his time: the separation of ethnology and art studies in the museum sector was a concern of his colleagues Albert Grünwedel and Otto Kümmel, which also resulted in the emancipation of Indian and East Asian art departments in the Berlin museums. “The task cannot be to force Eastern forms into the conceptual system tested on Western art, but to expand this system itself, to derive from the material of Eastern art the concepts that serve its interpretation and, on the broader basis thus gained, to find the common denominator that could provide the necessary basis for a world history of art. The path to the interpretation of Eastern art is to be sought from the analogy of Western methods, not through their transfer.” (pp. 246–247) Glaser sees the art-historical and aesthetic interpretation of East Asian art as a contribution to the art history of the world as the first task of the new discipline.

Glaser provided important impulses in another specialized field of East Asian art. As director of the art library, he took over a considerable collection of Japanese woodblock prints34 from his predecessor Peter Jessen (1858– 1926)35, and Glaser continued to cultivate this specialty. Here his interests coincided with those of Emil Orlik’s (1870–1932) pupil and Japan expert Fritz Rumpf (1888–1949)36: While the opinion of most museum people was still that Japanese woodcuts were not real art, Jessen, Glaser and Rumpf saw things differently, based on their experience and their stay in Japan. Glaser was unable to find a better expert to work on the Tony Straus-Negbaur collection37 than Fritz Rumpf, who had made a name for himself as an outstanding connoisseur with his Meister des japanischen Farbholzschnittes (Masters of Japanese woodblock prints)38. Rumpf also edited the later auction catalog39.

Glaser also made a name for himself with his work on Japanese theater, especially by organizing an exhibition on the subject (1930). As early as 1912, he had written Von den Formen des japanischen Schauspiels40 (On the forms of Japanese drama), and small articles on Japanese theater had even appeared in Japanese translation in 1912 (by the poet Kinoshita Mokutarō). At a time when Japanese theater was still little known in Europe, the Berlin exhibition generated a great response, especially since Glaser not only published a popular exhibition guide, but also a handsome volume accompanying the exhibition.41 The critical Otto Kümmel volunteered to act as editor of the volume as part of a new series called Nihon Bunka [Japanese Culture].

Curt Glaser dealt with East Asian art in a number of other works – around 60 in total, if you count the articles in the Berliner Börsen-Courier.

As part of his ongoing coverage of art events and trade, Glaser also made the acquaintance of Felix Tikotin (1893–1986), who owned a Japanese art shop on Kurfürstendamm before emigrating in 1933.42 It was certainly not without reason that Tikotin chose one of Glaser’s words as the motto for his memoirs: “When the Western way of life has completed its work of destruction in East Asia, the world will be poorer for the spectacle of an ancient and purely aesthetic culture.” Glaser closely followed the innovative and stimulating activities of the new art dealership43.

Glaser was a regular author with Bruno Cassirer (1872–1941)44. He made numerous contributions to the renowned journal Kunst und Künstler (1902–1933) edited by Karl Scheffler (a good friend of Glasers); independent works by Glaser, published by Cassirer, included a monograph on Edvard Munch (1917), Die Graphik der Neuzeit (1923), Ostasiatische Plastik (1925) and Amerika baut auf! (1932), a briskly written travelogue through the country where he was to spend his last years. He seems to have appreciated Cassirer, as can be seen from his two contributions to Cassirer-Festschriften45: “He represents a new type of art publisher for Germany, because he became a publisher for the sake of art, not as a publisher also including art in his business.”

Now a brief look at Glaser’s more important works on European art history. In Zwei Jahrhunderte deutscher Malerei46 (Two Centuries of German Painting), he attempted to depict early German painting as a whole. Of course, he did not have a collection of data and facts in mind: “It would have been possible to compile everything available and worth knowing, as Janitschek had done in his Geschichte der deutschen Malerei, which was published in 1890. But the intention was different. It was not intended to be a handbook or a reference work. The aim was not completeness in detail, but the coherence of the whole. And just as it is the art of sketching to emphasize the main features and suppress the less important, so here it was important to draw the broad lines of development, to highlight their main protagonists and suppress secondary phenomena in order to allow the essential features of a colourful painting to emerge clearly in a compact depiction.” 47 Glaser also treated Holbein 48 and Cranach monographically from this period. The latter book was published in the series Deutsche Meister (1921 ff.) edited jointly with Karl Scheffler49 by Insel Verlag and dedicated to his teacher Heinrich Wölfflin. In his Graphik der Neuzeit, Glaser only dealt with “works of printed art, [...] copperplate engravings, etchings, lithographs and woodcuts” and refrained from including reproductive prints. The extensive material is treated in periodized form – the three main sections cover the first and second half of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century. While the first part is subdivided according to technique (etching, lithography, woodcut), the regional arrangement seemed to make more sense for the following parts.

Glaser’s last work, Materialien zu einer Kunstgeschichte des Quattrocento in [Nord-]Italien was previously unpublished. An (imperfect) typescript was available in 1938, but who would have published it at the time? Moreover, the desirable illustrations would have been very expensive. In the USA, a Germanlanguage work of this size would have had no chance at all. Today the reservations against the emigrant no longer exist, and the question of costs no longer arises to the same extent, because the Internet brings excellent pictures into the house, so that they do not necessarily all have to be added to a book. But, as Glaser himself said: “The ideal of historiography is a timeless justice. But it proves again and again that even historical judgment is not independent of the artistic taste of an age.”50 While Glaser had written for an educated audience during his lifetime, largely dispensing with footnotes and scholarly apparatus, he had captivated his readers with his lively style, skillful choice of words and strong identification with the subject matter. But readers’ tastes have changed, and today the publication of the book should be regarded more as a historical document and a contribution to the appreciation of Curt Glaser. However, it is still an exciting read for anyone interested today!51

Note on the following list of publications: No effort has been made to achieve complete coverage. Regarding the many small articles in journals the reader is referred to Andreas Strobl’s monograph.

1