Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The Crowood Press

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

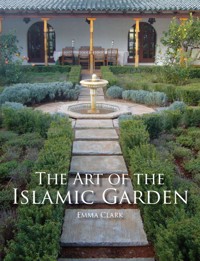

Islamic gardens are enchanting places. Just the names of some of the most beautiful gardens in the world - the Alhambra, the Generalife, the Shalimar - conjure up images of calm and even divine beauty. No visitor is left untouched by their magic. This new paperback edition of The Art of the Islamic Garden is an introduction to the design, symbolism and making of an Islamic Garden and it examines that magic, describes the component parts which allow a deeper understanding of the beauty. Topics covered include: history, symbolism and the Quran in relation to the traditional Islamic garden; significance of design and layout of the garden explained, geometry, hard landscaping and architectural elements and aguide to designing the garden with water, and recommendations for trees, shrubs and flowers. There is a unique account of the design and planting of HRH The Prince of Wales' Carpet Garden at Highgrove.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 548

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2010

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

First published in 2004 byThe Crowood Press LtdRamsbury, MarlboroughWiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

Paperback edition 2010

This impression 2014

This e-book first published in 2023

© Emma Clark 2004

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this publication is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7198 4358 7

Photograph previous page: Courtyard Garden,Damascus (Maktab ’Anbar)

Dedication

To my Mother,A true gardener

Contents

Preface

Acknowledgements

Introduction

1 History, Symbolism and the Quran

2 Design and Layout

3 Geometry, Hard Landscaping and Architectural Ornament

4 Water

5 Trees and Shrubs

6 Plants and Flowers

7 HRH The Prince of Wales’ Carpet Garden, Highgrove: a Case Study

Conclusion

Endnotes

Select Bibliography

Select Useful Addresses

Index

Preface

Even a glimmer of understanding of traditional Islamic art and architecture clearly reveals that its beauty is not simply surface decoration but is a reflection of a deep knowledge and understanding of the natural order and of the Divine Unity that penetrates all of our lives. This profound revelation was the principal reason that led me to enter the religion of Islam. There is no separation between the sacred and profane in a traditional Islamic society (or any traditional society, i.e. one that is centred on a transcendent principle) and this means that everything, not just the ritual prayer (salat) performed five times a day, is touched by the sacred. Everything that we do in daily life, from washing to eating to conducting business or growing plants, is performed in the full knowledge and faith that it has a ‘meaning in eternity’.1 So the underlying theme of this book is that the traditional Islamic garden, like all traditional Islamic art, has a profound message for all those ‘people who reflect’2 – that of being a reminder of who we are before our Maker.

Fig. 1. The fountain is in the Alhambra Palace, Granada.

The inscription above reads ‘Bismi’Llah ar-Rahman ar-Rahim’ (In the name of God the Most Merciful the Most Compassionate).

Studying Islamic art and architecture, and completing a master’s thesis on the Islamic garden and garden carpet at the Royal College of Art,3 opened my eyes to the meaning of art. Understanding something of the religion of Islam in general and Islamic art in particular, it became clear that all art, to a greater or lesser degree, should be the vehicle of a message of hope:4 it should remind us of what it means to be human, of our place in the universe and our role, as is said in Islam, as God’s vice-regent (khalifat ’Allah) on earth. It could be argued that any garden, since its main ingredient is God’s creation, carries this message, reminding us as it does of the beauty and unity of nature, especially in built-up environments – and by and large this is true. However, a garden constructed according to traditional principles, such as the Islamic chahar-bagh or four-fold garden, can be a much more potent testimonial than a garden planned with no such principles in mind. That is the main theme of this book.

In the increasingly difficult times in which we live, it is good to be reminded that gardens and nature transcend nationality, race, religion, colour and ideology: the Islamic garden is not only for Muslims – its beauty is apparent to everyone, especially to those ‘people who have sense’.5 The media shows a side of Islam that has little to do with its inward aspect, an aspect that is shared by the other two great monotheistic religions – that of moving closing to God. The Quran is a sacred presence to Muslims and its references to nature, like its description of the paradise gardens, are worth considering carefully when looking at the meaning of the Islamic garden or if considering making one yourself. It is hoped that this book, in revealing something of its design and cosmology, goes a little way towards throwing some light, not only on one of the great achievements of the Islamic civilization, but also on the beauty of the religion itself.

Today it is estimated that out of the approximately six billion people in the world, over one billion of them are Muslims and it is also estimated to be the fastest growing religion in the world.6 One journalist wrote in 1979, ‘No part of the world is more hopelessly and systematically and stubbornly misunderstood by us than that complex of religions, culture and geography known as Islam’.7 However, since then quantities of books have been published on understanding Islam,8 and certainly knowledge of this religion and culture has increased considerably. Teaching about Islam and the Islamic civilization in the Western world is also fairly widespread now, if not exactly mainstream. Twenty-five years ago in the United Kingdom we were taught about Christianity at school and nothing else. Today, most primary schools teach something of the other world religions, and I find children and teenagers under 20 years old know far more about Islam – and other religions – than their parents and grand-parents. In our cosmopolitan and ‘multicultural’ societies, the only way of combating ignorance, prejudice and fear is intelligent education about religions and cultures of the world other than our own.

The Visual Islamic and Traditional Arts Programme (known as VITA) at The Prince’s School of Traditional Arts where I am a tutor and lecturer, was founded in 1983 for the purposes of teaching, not only the principles and practice of the Islamic arts and crafts, but also the arts of the other great traditions of the world. Gradually, in the past few years an increasing number of people involved in education both at home and abroad are coming to VITA for advice on Islamic art teaching programmes for schools and higher education. Through art, beauty and nature, tolerance and understanding will hopefully increase. As everyone connected to the horticultural world knows there has been a huge surge of interest in the last ten years or so in anything and everything to do with gardens. Hopefully, a love of gardens may encourage some people to learn more about the religion and culture that has produced some of the most beautiful gardens in the world.

Acknowledgements

I would first of all like to thank Khalid Seydo very much indeed, not only for his drawings (Figs. 62, 74a-74d, 231) but also for the hours he generously spent in reading the text and making helpful (usually!) comments. Secondly, many thanks to Emma Alcock for all the trouble she took with her drawings (Figs. 5, 6, 30, 58, 59, 114, 136). I would also like to thank Dr. Khaled Azzam very much for his invaluable editorial comments.

I am extremely grateful to Mike Miller, principal designer of The Prince of Wales’ Carpet Garden and former managing director of Clifton Nurseries. He has been unfailingly helpful and generous with information and advice as well as providing photographs and plans of the Carpet Garden at both Chelsea and Highgrove.

I would like to express my gratitude to HRH the Prince of Wales who kindly allowed me to use his Carpet Garden as a case study in the design and making of a traditional Islamic garden in rural England. I would like to thank his staff as well, namely: David Howard, head gardener at Highgrove, Patrick Harrison, Nigel Baker and James Kidner.

I am indebted to the following friends and relatives who have been incredibly supportive in one way or another, giving editorial, practical and scholarly advice – from invaluable comments on the text and on geometric and garden design to Quran and hadith exegisis, as well as the identification of plants and allowing me to wander around their gardens – (in alphabetical order): Ms Fatma Azzam, Mr Nigel and Mrs Heather Alford, and Mr Martin Braund (three gardeners at Clovelly Court, North Devon), Mr Adnan Bogary and Mrs Summer Baghdady, Dr Harry and Mrs Laura Boothby, Professor Keith Critchlow, Mrs Jack Clark, Mr Jasper Clark and Ms Linda Rost, HRH Princess Haifa al-Faisal, Professor Richard Fletcher, HRH Prince Ghazi bin Muhammad and Princess Areej Ghazi, Mr Anthony and Lady Virginia Gibbs, Dr Julian and Mrs Alison Johansen, HRH Princess Johara bint Khalid, Ms Caroline Kinkead-Weekes, Mrs Debbie Lane for her great help at the Lindley Library, Dr Martin Lings, Mr Mustafa and Mrs Haajar Majzub, Mr. Khalil Martin, Dr Toby and Mrs Farhana Mayer, Mr Minwer al-Meied, Dr Jean-Louis Michon, Mr Khalid and Mrs Pascal Naqib, Professor Seyyed Hossein Nasr, Dr Hilali and Mrs Samya Noordeen, Professor Abdullah and Mrs Tybah Sharif-Schleiffer, Dr Reza and Mrs Nureen Shah-Kazemi, The Rickett family, The Hon John Rous, Dr Philip Watson, and the Zinovieff family.

Picture Acknowledgements

I am also indebted to the following colleagues and friends who have so kindly provided images: Paul Marchant (Figs. 17, 19, 41, 34, 138, 140), Taimoor Khan Mumtaz (Fig. 116), Sajjad Kauser (Figs. 18, 131, 137), Professor Jonas Lehrman (Figs. 139, 141), Michael Miller (Figs. 206, 207, 211, 213, 221, 226), Safina Habib (Fig. 25), Ririko Suzuki (Figs. 23, 84), Farid Aliturki (Fig. 66), and Patricia Araneta.

The British Library Oriental and India Office Collections (Fig. 26), The Al-Sabah Collection Kuwait National Museum (LNSIOR) Courtesy of Gulf International (Fig. 210), and Christie’s International (Fig. 102).

Finally, I would like to express my profound respect and gratitude to all those gardeners, mostly anonymous, who tend their gardens with painstaking love and care: they receive little outward show of thanks but provide more beauty and solace to uplift the spirit of many a passing soul than they are aware; and of course all thanks to the greatest gardener of them all, Mother Nature,

Al-hamdu li’Llah rabi’Allah ’min.

Introduction

This book offers an introduction to the design, symbolic meaning and planting of the traditional Islamic garden, as well as giving some practical ideas for those interested in making one for themselves – in the United Kingdom or elsewhere with a similar climate. It is not a history of Islamic gardens or a geographically comprehensive survey of them. Some may be inspired to make one of these gardens as a reminder of time spent abroad in countries as diverse as Morocco, Syria, Iran, India or Spain; or Muslims may wish to make one as a reminder of the gardens in the country of their birth or their relatives’ birth. Obviously it is not necessary to be a Muslim to make an Islamic garden, just as it is not necessary to be a Buddhist to make a Japanese Zen garden or a Christian to make a medieval knot garden. However, there is no doubt that it is far more enriching for the garden-maker or designer, when embarking on such a garden, to have some understanding of the culture that gave birth to it in the first place.

Fig. 2. Jardin Majorelle – Ironwork window-grille set within carved plaster surround.

Fig. 3. Courtyard, Azem Palace, Damascus.

Fig. 4. Generalife gardens, Alhambra Palace, Granada.

Fig. 5. Fundamental chahar-bagh (four-fold garden) plan, after the Taj Mahal garden.

Fig. 6. Court of Lions, Alhambra: water flows both from the central fountain into the rill below and from four fountains, one on each side of the court, towards the centre – reflecting the four rivers described in the gardens of paradise in the Quran: one of water, one of milk, one of honey and one of wine (see Chapter 2).

This book does not contain strict blueprints for designs but rather flexible ideas deriving from a fundamental theme – that of the chahar-bagh (from the Persian chahar meaning four and bagh meaning garden), as well as recommendations for planting. The classic chahar-bagh is the four-fold garden constructed around a central pool or fountain with four streams flowing from it, symbolically towards the four directions of space. Occasionally, the water is engineered to flow both from the central fountain ‘outwards’, as well as travelling ‘inwards’ from fountains placed at the ‘four corners’ towards the centre – as can be seen in the Court of Lions at the Alhambra (Fig. 6 and see Figs 31 and 32). Often paths are substituted for water. This could be said to be the quintessential plan of an Islamic garden – and there are many interpretations of it across the Islamic world, for example, it can be rectangular and not square (the Patio de la Acequia at the Generalife, Figs 40, 52 and 56) and it can be repeated on a kind of grid system, following irrigation channels (the Agdal gardens near Marrakesh); its symbolism is not particular to Islam but of a universal nature, founded upon a profound understanding of the cosmos – this is examined in Chapter 1. The plan can be adapted for your own garden according to individual circumstances and requirements, while the underlying meaning of being a reflection of the heavenly gardens remains the same and is relevant to all, Muslim and non-Muslim alike.

We all have different starting-points for our gardens depending on the size, situation (urban, suburban or rural), aspect, climate, soil and so on, so suggestions are made in Chapters 5 and 6 for a variety of trees, shrubs, plants and flowers, which may suit a more northern climate at the same time as being appropriate for an Islamic-inspired garden. Crucially, the fundamental four-fold lay-out should be retained, together with water in some form or other (see Chapter 4). It should be made clear from the outset that this kind of garden is a formal garden and on the whole is easier to adapt to an urban situation rather than a rural one. However, it is certainly possible to create a formal chahar-bagh in the countryside, providing it has some kind of separation from its surroundings – in the form of walls or high hedges, creating a ‘room’ for it. The case study in Chapter 7, HRH The Prince of Wales’ carpet garden at Highgrove, demonstrates how well this can succeed.

There is no substitute for actually visiting Islamic gardens around the world for a greater understanding and appreciation of them. The ones we are mainly looking at for inspiration are those created from approximately the tenth to the end of the seventeenth centuries, in the countries most obviously categorized as the traditional Islamic world: north African countries, the Near and Middle East, Turkey, Persia (present-day Iran) and the Indian sub-continent.8A The majority of the most outstanding Islamic gardens were created before the beginning of the eighteenth century when the influence of the Western European gardening traditions began to be felt.9 Until this time, from around the middle of the sixteenth century onwards – and at least a century earlier in Spain – this situation was in reverse: it was European gardens that were influenced by Eastern gardens, experiencing a kind of revolution, not so much in design as in plants and planting. This was initiated by the great number and variety of new trees, shrubs and flowers introduced from Turkey and further East by diplomats and travellers keen to find out more about the powerful and fast-expanding Ottoman empire.10

Fig. 7. The garden of the Dar Batha Museum, Fes, showing paths forming the chahar-bagh.

Fig. 8. Café at the foot of the mountains just north of Tehran. Guests sit or recline on metal beds covered in rugs, which are placed straddled over a fast-flowing stream.

Fig. 9. The ‘Garden of the Sultana’ showing pavilion and water, Generalife gardens, Alhambra.

However, to return to one of our main purposes here, that is, to look at some Islamic gardens which have survived until today for inspiration. A glance at just a few of these great gardens11 – from the expansive Achabal gardens (Kashmir) and the Bagh-i-Fin (Persia), to the more intimate gardens of the Alhambra and Generalife (Spain) and the courtyards of old Damascus and Fes – demonstrates the emphasis on water and shade, as well as on the strong integration between architecture and landscape, which distinguishes them from the gardens of the northern European tradition. In a North European country such as the United Kingdom the emphasis is, understandably, less on water and shade than on sun and the longed-for south-facing border. Indeed, most people still, in spite of all the health warnings, rush to bask in the sunshine as soon as it makes one of its rare appearances. It was only after visiting Iran and spending time in cafés at the foot of the mountains north of Tehran that I really began to understand the importance of water and shade, and to absorb the atmosphere of what an Islamic garden means. Here, cheap metal divans are placed across fast-running streams; rugs and cushions are laid out on the beds so that the visitor can sit crosslegged or lie on them and wait to be served with watermelon, tea and perhaps shisha or argile (water-pipe). Then one sinks back into the cushions looking up at the leaves of the chenar tree (Platanus orientalis) filtering the sunlight, listening to the sound of water running over the pebbles below and the phrase from the Quran, ‘Gardens underneath which Rivers flow,’12 is really brought alive. The experience is truly a foretaste of the Paradise gardens which all Muslims, and others too no doubt, hope to be their final resting-place.

When observing the formality of the chahar-bagh across the Islamic world, it is worth noting a fundamental difference between the gardens (the larger ones we are referring to here) of England and Europe, and the Islamic gardens: Muslims, indeed anyone brought up in a hot country, do not on the whole, like to walk purely for pleasure.13 First of all, it is generally too hot and secondly, what is the point of walking if you do not have a necessary destination in mind? As the reader who has stayed in a hot country for any length of time will know, this is completely understandable. Thus, after the two vital elements of water and shade, another important consideration (along with geometry, discussed in Chapters 2 and 3) is a place to sit: a pavilion at one end or in the centre, preferably somewhere near the water in order to catch a cooling breeze. Sir John Chardin’s (ambassador to Persia in the seventeenth century) observation that ‘The Persians don’t walk so much in Gardens as we do … they set themselves down in some part of the garden … and never move from their seat till they are going out of it,’14 is very relevant in understanding the ambience of the Islamic garden. It is far more focused on rest, relaxation and entertainment, as well as quiet contemplation, than a garden in England in which it is only possible to sit for two or three months of the year, the rest of the time being a damp, if beautiful, place to walk. In fact, Francis Bacon (1561–1626) commented the opposite about England, ‘It is very pleasant to be outside but not pleasant enough to sit still’.

Intention

When studying the art, architecture and landscape of another culture, in particular the Islamic culture, the intentions and mentality of all those skilled craftsmen, artists and designers who created them should be taken into account. In Islam the intention of a person is profoundly important. There is a hadith (a Saying of the Prophet Muhammad),15 which says that if anyone has intended a good deed and has not carried it out then God writes it down as a full good deed, but if he has intended it and has carried it out then God writes it down ‘as from ten good deeds to seven hundred times, or many times over’.16 This recalls a lesson that an English gardener, apprenticed in the art of Japanese gardens, brings across vividly in his book on Japanese gardens, when he learns the importance of how to approach a task: ‘The lesson that the spirit with which one performs any task, no matter how “menial”, is more important than getting it done cannot be ignored … the essence of that spirit is to be “centred”’.17 The apprentice needs to ‘centre’ himself before executing his craft and this means, very briefly, that the soul needs a certain discipline and maturity before proceeding to a more sophisticated level of the craft. This could well be applied to a student or apprentice of any traditional art or craft, especially in Islam where a good intention is so highly rewarded. As will be mentioned more than once in this book, the crafts and the spiritual orders in Islam, as with the medieval craft guilds of Christendom, were closely allied.

Therefore, the intention or the spirit behind creating a garden is fundamentally important in both understanding gardens made by others and in a garden made by oneself. There is no doubt that a person’s surroundings both reflect the soul of that person as well as, conversely, having an effect upon that person’s soul. As the Buddha said, ‘If a man’s mind becomes pure, his surroundings will also become pure’.18 At the same time, if the surroundings are ‘pure’ – the greatest example being virgin nature and, secondarily (in the absence of sacred architecture), a beautifully-ordered garden – it will help the soul of the person within those surroundings towards a certain inward tranquillity, if not necessarily ‘purity’. The kind of purity the Buddha is referring to requires life-long disciplined spiritual work, a path for which only some are destined. Few would argue that it is easier to feel peaceful and contemplative in a beautiful garden or virgin nature than in a city with tall buildings, deafening traffic and crowded streets.

Types of Gardens

Apart from the chahar-bagh mentioned above there are several other garden types in the Islamic world, the main distinction being between the larger outward-looking gardens and the smaller inwardlooking courtyard ones. The larger ones are generally known as bustan (the Persian word for ‘orchard’) and may have formerly belonged to palaces, such as the Jardin Menara or Jardin Agdal, now public gardens on the outskirts of Marrakech. They both consist of vast still pools surrounded by olive groves, fruit trees and palm groves. The largest, the Jardin Agdal, could be said to be a chahar-bagh multiplied many times over, in that its enormous central expanse of water is surrounded by smaller irrigation pools with geometric water-channels running between them. The whole area is surrounded by walls within which are seemingly endless square plots of fruit trees – oranges, lemons, apricots, figs and pomegranates – all divided geometrically by the irrigation channels and with raised walkways and avenues of olive trees in between. These large gardens are not flower gardens as we understand them, but cool, green places for sitting in and picnicking under trees near water while children play. Another famous large open garden, this one focused almost entirely on terraces of water and pavilions, is the Shalimar Gardens in Lahore, built in the seventeenth century by the Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan (see Chapter 4 and Fig. 116).

Fig. 10. Menara Gardens, Marrakech.

Fig. 11. Agdal Gardens, Marrakech.

Fig. 12. Menara Gardens – picnicking under the olive trees.

Fig. 13. Traditional courtyard house, Marrakech.

Fig. 14. Riyadh al-Arsat, Marrakech, a small area in this large courtyard garden.

Fig. 15. One of the smaller courtyards, Azem Palace, Damascus.

Fig. 16. Large central courtyard, Azem Palace, Damascus.

The smaller gardens are usually formed by the courtyards of the inward-looking traditional Arab-Islamic house. These are all adaptations of the chahar-bagh form and can vary in size from small, as in approximately six metres square, to as large as twenty metres by about fifteen. In old Damascus, the large houses of the rich officials, such as the Palace of As’ad Pasha al-Azem, contain a series of courtyards ranging from the largest, approximately twenty-five by twenty metres, to the smallest, which is about seven metres square, all with fountains or pools. Al-Azem governed Damascus for fourteen years and made such a huge fortune that when it was confiscated by the Ottoman Sultan in 1758, the currency of the Empire had to be re-valued! Maps of traditional Islamic cities such as Damascus, Fes or Aleppo are fascinating to look at: there are no main roads or open spaces, just an extraordinary dense network of narrow winding lanes and alleys and the courtyard squares of houses, every so often divided into neighbourhood quarters each with its own mosque and bread oven. The map of Damascus made by the French in the 1930s shows that each house has its own courtyard, fountain and trees.18A Many travellers have observed the contrast between the dark narrow streets and the high and seemingly impenetrable outer walls of the houses with the brilliance of the courtyards within. ‘Are you disappointed, as you tread these streets by these repulsive walls? Do you tremble lest the dream of Damascus be dissolved by Damascus itself?’ wrote an American melodramatically in 1852, continuing, ‘Oh little faith! Each Damascus house is a paradise!’.19

Another type of garden is the gulistan or rosegarden, which may take up one area of the bustan, or may simply consist of a wall or arbour with climbing roses or a few shrub roses in a courtyard. The word gul is used as a general term for flower in Persian, as well as specifically for the rose. An abstracted version of a gul is the dominant motif in many tribal carpets, from Baluchistan to Anatolia through to the wide range of Turkomen rugs and carpets.

Fig. 17. The tomb of Itimad ud-Dawlah, Agra, at the centre of a chahar-bagh.

Fig. 18. Jahangir’s tomb showing four-fold design of garden with large square central pool, Lahore, Pakistan.

Fig. 19. The Taj Mahal at the head of a large chahar-bagh.

Then there is the mausoleum garden, a form which came into its own in Mughal India. This is a variation on the chahar-bagh theme; instead of a pavilion for sitting in, the tomb of the deceased is placed in the centre of a large chahar-bagh, symbolizing the meeting of the immortal soul with God at death. The mausoleum gardens look outward from the centre toward the four directions of space. Three of the most famous examples are: the mausoleum of Itimad ud-Dawlah, who was the Lord High Treasurer under the Mughal Emperor Jahangir (1605–27); the tomb of Jahangir himself; and the Taj Mahal. The Taj Mahal, built by Shah Jahan for his wife, Mumtaz-I-Mahal, is the supreme example of a mausoleum garden, the tomb itself set at the head of the chahar-bagh looking down its main axis towards the raised pool in the centre.

Rawdah literally means ‘garden’ in Arabic but the term is applied specifically to the small area in the Prophet’s mosque at Medina between his tomb and the pulpit (minbar). It is called this because of the Saying of the Prophet, ‘Between my house and my pulpit is a garden [rawdah] of the gardens of paradise’. Today, when worshippers visit the mosque at Medina, this area is always the most crowded, since everyone longs to be with the Prophet in his garden in Paradise.

All of the above gardens may employ the chaharbagh geometric design in some form or other and in the larger ones, such as the Jardin Agdal, it may be repeated several times to form a regular grid pattern. This is clearly shown in the great classic garden-carpets such as the Aberconway (Fig. 210) in which the bird’s-eye view allows the onlooker an all-encompassing vision. The ordered geometric lines are either irrigation channels or paths and the square or rectangular plots usually contain one specific fruit tree or vegetable each. The separation between the flower garden and the potager or vegetable garden was not as strictly imposed as seems to be the case in many of the ninteenth-century estates in England and Europe. In the Victorian era, the separate walled vegetable garden became an important feature of the ‘stately home’ and it is only relatively recently that mixing flowers with vegetables has come back into fashion. Of course, the cottage garden of rural labourers at this time contained vegetables, fruit and flowers – indeed, flowers were only for the fortunate ones who could spare a little ground from their vegetable-patch (see Chapter 6). A good example of the recent mixing of flowering plants and produce is the walled garden at Highgrove, which echoes the Islamic – and, as we shall see in more detail in the next chapter, universal – theme of the four-fold design with a pool in the centre. Arbours of roses and tunnels of sweet peas form part of the symmetrical lay-out with fruit and vegetable plots in between.

The Quran, Symbolism and Plato

In the modern world there is a sharp division between everyday life with all its material requirements and preoccupations, and a spiritual life – if we are fortunate enough to have one. For very many people living in the Western world, the former has all but destroyed the latter. In Islam, as in the other two Abrahamic religions,20 man21 is seen to have fallen from his primordial state in the Garden of Eden when he was at peace with his Lord and in a state of unity with Him and the cosmos. In order to regain this primordial state of unity with God, man needs all the help possible to remind him of his theomorphic nature and his role as vice-regent (khalifat ’Allah) of God on earth. Human beings are forgetful, becoming so immersed in the details of earthly existence that we no longer recognize the signs that can jolt us back to remember what it means to be human. One of the greatest of these signs is Nature herself. The Quran points out many times over, the importance of ‘signs’ or ‘portents’, ‘symbols’ or ‘similitudes’ (variously translated from the Arabic word aya) in the natural world, none of which are too small or too trifling to be a reminder of God – from a date-pip to a gnat (‘God is not ashamed to strike a similitude even of a gnat or aught above it’, Quran, II:24). Aya is also the word for a verse of the Quran, implying that every verse is a sign of God. Indeed, this is the case, since in Islam the greatest miracle is the Holy Quran itself, the Word of God made manifest. It is generally agreed that the Quran, being the ‘Word made Book’ corresponds to Jesus Christ in Christianity, who is the ‘Word made Man’.

Fig. 20. Virgin Nature, the greatest sacred art. In the Quran there is a constant refrain that we should meditate upon Nature, since her beauty and diversity is one of the great symbols that open a door towards the Creator.

In Plato’s ‘Theory of Art’,21A he suggests, through the dialogue about the bed, that he considers everything created by the carpenter or the painter or other artists as being at a ‘third remove from reality’. Their objects are simply distant representations of the ‘throne of truth’. The ‘true form’ or archetype was made in Heaven (by, in monotheistic terms, God Himself) and therefore everything in the created world including plants, animals, the earth and sky and the planets, are reflections or mirror-images of these heavenly archetypes. Islam embraced the Platonic tradition, and those who understand, those ‘people who reflect’ (a phrase repeated throughout the Quran) see through the phenomena of the natural world in all its infinite glory to the underlying truth: Nature, as a sign of God, both veils and reveals. So the beauty of the natural world is one of God’s greatest symbols and through meditation on its glories we can, as with all true sacred art, retrace a path back to Truth. This is indeed what sacred art is centred upon – as Plato is famously credited with saying, ‘Beauty is the Splendour of the True’.22 In Islam there is no beauty outside of God23 and all traditional art across the Islamic world, demonstrates, to a greater or lesser extent, the truth of this and of Plato’s words. In a general sense, the traditional Islamic chahar-bagh, the archetype of which are the paradise gardens described in the Quran (see Chapter 1), is itself one of these symbols. It is a means whereby we are roused from a passive, unquestioning acceptance of the sensory world to an awareness of both the immanence and the transcendence of God.

Islamic Gardens in a Different Environment

The Islamic garden, as is well-known, was born in a hot climate. Although snow falls in many areas of the Islamic world, such as Turkey, parts of Jordan and Iran, and temperatures can reach well below zero, there is nevertheless a far greater amount of heat and sunshine than in northern climates. So the gardener or designer will understand from the outset that simply emulating the gardens of the East, such as Bagh-I-Shazdeh (the Prince’s garden) in Mahan, Iran or those nearer to home such as the courtyards and gardens of the Alhambra and Generalife (Figs 21, 24 and 28–29) is neither possible nor necessarily desirable in a damper climate. What is possible and desirable in our increasingly ‘multi-cultural’ world, is a merging of Islamic design principles – speaking as they do of a universal vision of the cosmos – with northern climactic conditions. The results will hopefully have a strong appeal to people from whatever background, country or religion at the same time as encouraging an awareness of the beauty and underlying universality of what is often considered an alien culture.

Fig. 21. Pool garden at the Alhambra.

The principal elements of all Islamic gardens, of whatever type and wherever they may be, are water and shade; so, much thought is required in making such a garden in a climate where heat from the sun is the sought-after and cherished element, while water and shade are plentiful and taken for granted. Therefore, on one level, the garden designer is searching for a new language of gardening, a marriage of Islamic design principles with planting more appropriate to northern climes. On a more profound level the person wishing to make an Islamic garden may be attracted by its role as a kind of sanctuary on earth, as well as being a foretaste of the Heavenly Gardens.

The great appetite for learning about different gardening traditions today is a sign that many people genuinely want to understand something of the cultural and spiritual vision that gave birth to some of these traditions. Essentially, the Islamic garden, like the Zen Buddhist garden, is an embodiment of a spiritual vision. Based as it is on the universal laws of Nature and the cosmos it may inspire people from a wide variety of backgrounds and geographical locations to interpret its ideas for themselves. The universal vision embodied by the Islamic garden may speak to everyone from whatever background, country or religion.

Hopefully, in the following chapters, the reader may learn something of the important symbolism of the Islamic garden as well as its design principles and how to combine these with suitable planting in order to create this ‘new language’. These principles may be adapted to a site but should not be fundamentally changed, since this would upset the underlying meaning. The planting is more flexible and can be altered according to the climate, soil, aspect and other environmental considerations without the design principles being altered significantly.

Fig. 22. The walls of the Carpet Garden at Highgrove, from the Orchard Room side. They are constructed from local stone with rendered and painted concrete – to give a Cotswold–Mediterranean look with an almost Aztec sense of mass!

On conquering different countries, the religion of Islam to a certain extent embraced these countries’ very varied cultures and in turn transformed them. This is true of the art, architecture and way of life all over the diverse regions of the Islamic world. It is interesting to observe that in the countries where Islam has recently spread, such as Northern Europe and North America, the mosques that have been built in the last thirty to forty years are by and large not examples of good design.24 Perhaps more time is needed to understand how to combine traditional Islamic design with the indigenous architecture and materials of these countries, as well as with modern western design in general. With gardens it should be an easier task to marry the two forces together in a pleasing, harmonious and meaningful way. After all, Islam has spread to widely differing countries and climates, from Africa to Turkey to Indonesia and China, so it is a religion and culture that is flexible and is used to adapting local art to its own quintessentially Islamic spirit and vice-versa. Now it is the turn of more northern countries to absorb and interpret the Islamic vision within indigenous gardening traditions to create something identifiably Islamic and yet at home in the country concerned. There are few examples to cite here, the most well-known probably being the carpet garden at Highgrove (see Chapter 7; there is also the Mughal-inspired garden at Manningham Park, Bradford). This works well, largely because, as mentioned above, it is secluded behind walls and does not attempt the impossible – to blend into the very English garden surroundings. This is in keeping with the Islamic idea of creating a sanctuary, one of the features of the desert gardens, and the Persian pairidaezas (hunting-parks) both areas isolated from their surroundings by boundary walls and planting.

So, what is an Islamic garden exactly, and in what ways does it differ from, or is similar to, other gardens? How can we apply its principles and ideas to our own gardens? It is hoped that this book will answer some basic questions as well as offering some explanation of the more esoteric meaning underlying the form and function of the Islamic garden. Hopefully, also, readers may be inspired to take up some of the ideas and apply them to their own gardens. When thinking about the Islamic garden and how it may be possible to design and make your own, it is inspiring to read the words of one of the greatest garden designers and writers of the last century, Russell Page:

When I come to build my own garden it can scarcely take another form than the one which is a reflection of its maker. If I want it to be ‘ideal’, then I too must set myself my own ideal, my own aim. Now, as for a painter or a sculptor or any artist comes the test – what values does the garden-maker try to express? It seems to me that to some extent he has the choice. He may choose the easy way and design a garden as a demonstration of his technical skill and brilliance, go all out for strong effects or see the problem as one of good or bad business and so plan accordingly. Or he may try to make his garden a symbol and set up as best he can a deliberate scaffolding or framework which nature will come to clothe with life.25

This last sentence puts the making of an Islamic garden in a nutshell, since ultimately the chahar-bagh is a symbol, a symbol of the Heavenly Gardens. Hopefully, this book will give the reader ideas for setting up the framework for the symbol and for clothing it with life.

The Chahar-Bagh in the Modern World

One of the main objectives of this book is to show that, in an increasingly urban society, the traditional Islamic four-fold garden, the chahar-bagh, could be developed in the United Kingdom and northern Europe, and other parts of the world with a similar climate. There is increasing evidence that more people are finding that a garden, however small, can become a source of sanity in an increasingly complex and frenetic world. The emphasis of the Islamic garden on peace and contemplation is what many city dwellers find most attractive about it. In desert regions, the inhospitable environment is shut out by means of high walls and evergreen trees – usually conifers of some sort, as they can withstand the wind and lack of water – to create a sanctuary within. In the modern city today the same principle holds true, that of shutting out the environment: but instead of the purity of the hard, empty, arid desert, it is the noisy, polluted, traffic-ridden, crowded streets. In fact the traditional Arab-Islamic town house (Fig. 13), still to be seen in the medina (old city) of some Muslim towns such as Fes, Rabat, Marrakech or Aleppo, was always built a around a central courtyard, separated from the city by high walls. The focus of these courtyard houses (the courtyard being a miniature garden) is inwards and upwards, symbolically towards the heart and towards God. This courtyard was, and still is, the inner sanctum, the heart of the house reserved for the family. As the great Egyptian reviver of traditional architecture and city-planning, Hassan Fathy, wrote, ‘The best definition of architecture is one that is the outcome of the interaction between the intelligence of man and his environment, in satisfying his needs, both spiritual and physical’.26 Today, an inner sanctum can be recreated in the back or front garden of many an urban dweller.

Fig. 23. The Paris Mosque, a good example of a twentieth-century mosque and courtyard in Europe, built in traditional North African style.

CHAPTER 1

History, Symbolism and the Quran

The first Muslims came from the Arabian desert: the Prophet Muhammad himself, like most young Arab boys at that time (sixth century AD) spent his early childhood brought up by a foster-mother from one of the nomadic desert tribes. It was believed that the demanding desert environment and nomadic way of life would instil the virtues of steadfastness, strength and courage into boys at an early age, which would stand them in good stead in adulthood. As far as is known, there is no history of gardens as we understand them in Arabia at this period: a date palm tree (Phoenix dactilifera) and water – the oasis – was a garden. It was not until Islam conquered other countries with civilizations of their own, in particular, Persia, that the Islamic garden can be said to have been born. Here, Islam absorbed the already well-established tradition of hunting-parks (pairidaeza) and royal pleasure gardens and invested them with a whole new spiritual vision.

Fig. 24. The ‘Garden of the Sultana’ in the Generalife gardens.

A glance at the art and architecture of the Islamic world clearly shows the tremendous variation of artistic expression – from the Kairouine mosque in Fes, to the Ibn Tulun mosque in Cairo, to the Friday Mosque in Isphahan, to take just three examples; and they all have rich art and craftsmanship adorning them. Each geographical location with its indigenous people, cultural characteristics and gifts, has adapted the Islamic vision and principles to achieve pinnacles of art that are both reflections of the land in question but which are recognizably true manifestations of the Islamic spirit; and this is no less true with Islamic gardens. Across the Islamic world these gardens show a great variation of style, reflecting practical and environmental factors, as well as indigenous cultural ones: factors such as topography, availability of water and purpose or type of garden. These range from the vast open gardens, such as the spectacular Shalimar Bagh (‘Abode of Love’) in Kashmir where water can be collected and channelled from the mountains, to the smaller, inward-looking courtyard gardens (which are our main interest here) of traditional cities such as Fes or Damascus. Like Islamic art and architecture, however richly varied these garden styles may be, they nevertheless retain the same principles and are expressions of the Islamic spirit.

If the individual gardener or designer skilfully links together Islamic design with local factors such as climate, materials, architecture and gardening traditions, then there is no reason why Islamic gardens should not succeed in a wide range of geographical areas in the world – from the South of France to Scotland, or from Venezuela to Canada. However, as this book is at pains to point out, making a successful Islamic garden in a part of the world that seems alien to the concept, requires some knowledge of its history, symbolism, planting traditions and variety of styles across the Islamic world. Thus, understanding of the cultural context is helpful and important when looking for inspiration and practical ideas.

History

The idea that Paradise is a garden is a very ancient one. It pre-dates Islam, as well as Judaism and Christianity and the Garden of Eden by centuries, seeming to have its origins as far back as the Sumerian period (4000BC) in Mesopotamia. Here, a paradise garden for the gods is mentioned in the first writings known to man. The Babylonians (c.2700BC) later described their Divine Paradise in the Epic of Gilgamesh: ‘In this immortal garden stands the Tree… beside a sacred fount the Tree is placed’.27 So already we have the two indispensable elements of the Paradise Gardens of Islam: water and shade. In the Quran these gardens are called the jannat al-firdaws, jannat meaning ‘gardens’ and firdaws meaning ‘paradise’. The word janna (singular) can also mean ‘paradise’. All the other words mentioned describing gardens such as chahar (‘four’), bagh (‘garden’), bustan (orchard) and gulistan are farsi words (the Persian language), clearly indicating where the earthly form of the Islamic garden originated. It was the unique impact of the Islamic revelation on the ancient Sassanid and Achaemenian civilizations of Persia with their pairidaezas (walled hunting-parks) and sophisticated irrigation systems, such as those of Cyrus the Great’s gardens at Pasargardae, that ultimately brought the Islamic garden into being. The English word ‘paradise’ itself comes from the ancient Persian word pairidaeza, pairi meaning ‘around’ and daeza meaning ‘wall’.

Fig. 25. Palm grove, Medina.

There are many references to the fountains, flowing waters and perfect temperate climate in the descriptions of paradise in the Quran, where the blessed shall be shaded by ‘thornless lote-trees and serried acacias’ and ‘palms and vines’.28 In hot and dry environments, water is understandably viewed, whether rain or a spring, as a direct symbol of God’s mercy and rain is described throughout the Quran as a mercy and as life-giving (see Chapter 4). To those brought up in countries where rain is frequent (and the popular idea of paradise is a desert island with a palm tree!) it is all too easy to take water for granted and be unaware of how much a lush garden with a green canopy of shade and flowing water means to inhabitants of countries with baking hot desert climates. It is no accident that green is the colour of Islam – it is the colour used over and over again to describe the gardens of paradise, where the faithful recline on ‘green cushions’ in ‘green shade’.29 Not only is it the colour of all vegetation, appearing young and fresh in the Spring, symbolizing growth and fertility, but it is the antithesis of the monotonous sandy-browns of the stony desert; it offers a longed-for soothing and gentle relief to the eyes. A famous English gardener writing at the beginning of the twentieth century gives a very evocative description of the unavoidable heat and longing for coolness and green foliage when trekking in Iran:

Imagine you have ridden in summer for four days across a plain; that you have then come to a barrier of snow-mountains and ridden up that pass; that from the top of the pass you have seen a second plain, with a second barrier of mountains in the distance, a hundred miles away; that you know that beyond these mountains lies yet another plain, and another; and that for days, even weeks, you must ride with no shade, and the sun overhead, and nothing but the bleached bones of dead animals strewing the track. Then when you come to trees and running water, you will call it a garden. It will not be flowers and their garishness that your eyes crave for, but a green cavern full of shadows and pools where goldfish dart, and the sound of a little stream.30

Fig. 26. Persian miniature showing high walls surrounding a house and garden, late-fourteenth century.

The Persians, as noted above, were one of the earliest peoples to cultivate gardens, parks and huntinggrounds – their pairidaezas by definition were walled areas. Thus we immediately have the idea of an area isolated from its surroundings, shutting out a difficult environment to protect an area of fertility and ease within. It is in the nature of paradise to be hidden and secret, since it corresponds to the interior world, the innermost soul – al-jannah meaning ‘concealment’ as well as garden,31 echoing the hortus conclusus of the medieval monastic garden. Thus the chahar-bagh is often represented in exquisite miniature paintings as surrounded by high walls. The courtyard of a traditional Arab-Islamic house in a city is a chahar-bagh in miniature; there may not be room for many plants and flowers but there is always water, usually a small fountain in the centre with possibly one palm tree or some plants in pots. These houses are often quite high with four stories or more and a flat roof on which one can sleep on hot summer nights. The windows rarely open out onto the street; instead, they look inwards, usually with balconies, to the courtyard and the miniature paradise garden within. When entering one of these houses, in order to maintain privacy from the street, the entrance corridor bends so that passers-by cannot peer in too far.

Fig. 27. Riyadh El-Arsat, Marrakech, fountain at centre of four paths.

The plan on which the Arab-Islamic house is based, also the plan of the chahar-bagh, is inherited from the ancient prototype originating in Mesopotamia. Here they made maximum use of what little water was available and built their houses of mudbrick around enclosures or courtyards with a fountain or small pool in the centre. This kept the adverse conditions outside, while simultaneously creating a cooler, cleaner, refreshing refuge within. Under Muslim direction, this architecture also reflected the clear separation between the public and private domains in a traditional Islamic society. This distinction between the public and private domains became one of the principles of traditional Islamic architecture and, by extension, the traditional Islamic four-fold garden. The house opens inwards to the heart rather than outwards towards the world. The heart, the courtyard, represents the inward (batin), contemplative aspect of human nature. The modern villa-type house, in contrast, represents the opposite, the outward (zahir), worldly attitude. The traditional house may be in the middle of the bustling medina (old city) – of Marrakech for example – but when the door to the street is shut the visitor enters a totally different world: it is immediately quiet since the high, thick stone walls keep out the noise and bestow a kind of muffled silence on the interior, not dissimilar to entering a church. The gentle murmur of a fountain in the centre draws the visitor in, contributing to the atmosphere of inward reflection. At night these small courtyards (often about six metres square or less) are quite magical: sitting on a rug or cushion on the stone floor, one’s gaze is inevitably drawn upwards to the stars in the sky. It is a beautiful example of how traditional architecture can affect a whole way of life and have an impact upon the soul.

‘As desert dwellers, the notion of invisible hands that drove the blasts that swept the desert and formed the deceptive mirages that lured the traveller to his destruction was always with them,’ writes one religious scholar.32 So, for the pre-Islamic Arabs, accustomed as they were to living in a hostile environment, the smallest drop of water or the slightest indication of nature’s greenness was considered precious and sacred, its rare appearance the work of ‘invisible hands’. To them the oasis was a garden. So an extension of this oasis, more water and more trees, as mentioned in the Quran, was miraculous and heaven-sent. They already revered Nature as life-giving and as a sign of the mysterious power that guided the universe, and were familiar, as it were, with the unseen world of the spirit. Thus, when the Quran was revealed to the Prophet Muhammed in the early part of the seventh century AD, with its promise of gardens of paradise to the faithful and righteous, it was perfectly natural for the Arabs to accept this. The religion of Islam reconfirmed ancient and universal truths, imbuing them with a rigorous spiritual vision focused on one single invisible God. So when the Arab Muslims conquered Persia, Syria – Damascus in particular – and Spain, all countries with an abundance of water compared to Arabia, it is not surprising that they believed they had found their earthly paradise.

The Quran and Symbolism

There are many references in the Quran to the paradise gardens, the jannat al-firdaws promised to ‘those who believe and do deeds of righteousness’.33 Various epithets are attached to the word jannat (gardens) in order to describe the qualities that they possess: for example, jannat al-khuld34 – khuld meaning immortality or eternity; jannat al-naim35 – naim meaning bliss, delight or felicity; jannat al-ma’wa36 – ma’wa meaning refuge, shelter, abode. Also jannat ’Adn37 is mentioned – the Garden of Eden, suggesting the peace and harmony of mankind’s primordial state. From these descriptive words attached to jannat, we see that the Islamic paradise gardens are not only blissful and eternal, but they are also a refuge or sanctuary, a sheltered and secure retreat (khalwa meaning ‘retreat’ is also a term used) far away from the disquiet of the world. However, the phrase most often used (over thirty times) is Jannat tajri min tahtiha al-anhar, ‘Gardens Underneath which Rivers Flow’.38 Even in translation the repetition of this phrase has a soothing rhythm to it and, closing one’s eyes, it is possible to imagine being in a garden with water flowing through it (Figs. 29, 31 and 40).

‘But the God-fearing shall be amongst gardens and fountains.’39 Rivers flowing, water and fountains are the most powerful and memorable images one retains after reading the portrayals of the paradise gardens in the Quran. There is no doubt that the reason that water is the essential element in an Islamic garden is both because of the lack of it in the desert lands of Arabia and because of the importance placed upon it in the Quran (see Chapter 4). The Almighty knew that in order to tempt his flock back onto the ‘straight path’ (al-sirata mustaqim),40 He must promise them rewards in the Afterlife that they would understand and desire and which they already revered for their life-giving properties – such as water and shade. Islam gave the first Muslims the knowledge and faith that these two elements, together with the rest of the natural world, were not to be worshipped for themselves alone: they must be revered for what they represent. Nature and beauty are outward symbols of an inward grace. Throughout the Quran the faithful are exhorted to meditate upon these signs or symbols, since everything in the created world is a sign or symbol of God: ‘So God makes clear His signs for you; haply you will understand.’ (II: 243) The Quran also refers to the mediocrity and ephemeral nature of this lower life compared to the happiness of the life everlasting and the gardens of paradise: ‘The present life is naught but a sport and a diversion … the world to come is better and more enduring.’ (XLVII:38)

Fig. 28..

Fig. 29..

Gardens of the Alhambra, Granada.

Human beings would cease to be truly muslim, literally in submission to God, if they were to revere the created world as an end in itself (see page 33). The world should be seen for what it is – an illusion (maya in Hinduism) that both veils and reveals the archetypal heavenly world. When a civilization is centred on the sacred, whether it be Islamic, North American Indian or medieval Christian, the practical is always inextricably linked to the spiritual. This is the language of symbolism – linking the everyday practical activities back to their heavenly archetype. But human beings are forgetful and need to be continually reminded that the things of this world are transparent and not an end in themselves. This is where, firstly, religion41 comes in, and secondarily, sacred art. The Islamic garden can be seen as a kind of open-air sacred art, the content, form and symbolic language all combining to remind the visitor of the eternal, invisible realities that lie beneath outward appearances.

Jannat tajri min tahtiha al-anhar, ‘Gardens Underneath which Rivers Flow’: the idea of water flowing ‘underneath’ probably arose from the demands of a desert existence where the only source of water for most of the year was from the oases or underground irrigation systems such as the qanats in Persia. In the gardens themselves, the water is to be seen and experienced; in order to irrigate the flower-beds, it has to flow in straight channels and rills, often under the pathways, thereby giving the visitor the impression of actually being in a garden ‘underneath which rivers flow’. On a more profound level, water flowing underneath suggests the nurturing of the ‘garden within’, the ‘Garden of the Heart’, by the ever-flowing waters of the spirit, which serve to purify the soul of those on the spiritual path (al-tariqah). Indeed, water is symbolic of the soul in many sacred traditions, its fluidity and constantly purifying aspect is a reflection of the soul’s ability to renew itself, yet always remain true to its source (see Chapter 4). The apparently endlessly flowing water in the Shalimar Gardens in Lahore or the gardens of the Generalife at the Alhambra are some of the most evocative representations of the Islamic gardens of paradise anywhere in the world: the sound of water not only muffles the voices of other people but has the miraculous effect of silencing one’s own thoughts and allowing an overwhelming sense of peace to descend.

In Islam there are two main divisions in the Afterlife, heaven or paradise, and hell: the division between those who are saved and those who are not saved – and within these there is a hierarchy of many degrees.42 It is written in the Quran: ‘Whoso followeth My guidance, there shall no fear come upon them, neither shall they grieve’.43