7,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Open Book Publishers

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

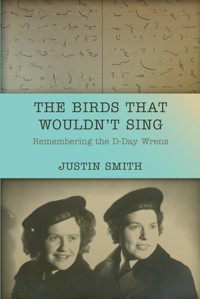

This compelling book offers a unique perspective on D-Day and its aftermath through the personal testimonies of the Wrens who worked for Admiral Sir Bertram Ramsay during Operation Overlord. Drawing on public and private archives, it reveals the untold stories of the women serving in the Women’s Royal Naval Service (WRNS), balancing their wartime contributions with the strictures of secrecy and censorship. The narrative is framed by letters from these Wrens, which provide intimate glimpses into both the personal and professional challenges they faced during World War II.

The book captures the atmosphere of war as experienced by British auxiliaries. It highlights the Wrens' vital but often overlooked role in the D-Day planning effort and beyond, revealing the surreal coexistence of the ordinary and extraordinary in wartime. Focusing in particular on the wartime archive of one of the Wrens, Joan Prior, the author brings to life the contribution of these women to the war effort, while also offering insights into British, French, and German morale and culture. This thoughtful and moving account adds depth to the broader historical narrative of World War II, making it a valuable addition for both the general reader and the professional historian.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Ähnliche

THE BIRDS THAT WOULDN’T SING

The Birds That Wouldn’t Sing

Remembering the D-Day Wrens

Justin Smith

https://www.openbookpublishers.com

©2024 Justin Smith

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the text; to adapt the text for non-commercial purposes of the text providing attribution is made to the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work).

Attribution should include the following information:

Justin Smith, The Birds That Wouldn’t Sing: Remembering the D-Day Wrens. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2024, https://doi.org/10.11647/obp.0430

Further details about CC BY-NC licenses are available at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

All external links were active at the time of publication unless otherwise stated and have been archived via the Internet Archive Wayback Machine at https://archive.org/web

Updated digital material and resources associated with this volume are available at https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/0430#resources

Information about any revised edition of this work will be provided at https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0430

Copyright and permissions for the reuse of many of the images included in this publication may differ from the above. This information is provided in the captions and in the list of illustrations. Every effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders and any omission or error will be corrected if notification is made to the publisher.

ISBN Paperback: 978-1-80511-419-2

ISBN Hardback: 978-1-80511-420-8

ISBN Digital (PDF): 978-1-80511-421-5

ISBN Digital eBook (EPUB): 978-1-80511-422-2

ISBN HTML: 978-1-80511-423-9

DOI: 10.11647/OBP.0430

Cover image: ‘Ginge’ Thomas and Joan Prior (studio portrait, St. Germain-en-Laye, November 1944). Private Papers of Joan H. Smith

Cover design: Jeevanjot Kaur Nagpal

For my brother,

For the life of Joseph Anthony Smith (1989–2023)

And to the service and memory of all the ‘Ramsay Wrens’

Table of Contents

Acknowledgements

List of Figures and Videos

The Wrennery

Prologue: Letters from an Unknown Woman

PART I —Overlord Embroidery

1. Wrens’ Calling (London, 1942–1944)

2. Coming of Age (Southwick Park, Summer 1944)

PART II — The Far Shore

3. Liberation (Granville, September 1944)

4. The Cutty Wren (Saint-Germain-en-Laye, Autumn 1944)

PART III — The Song of Joannah

5. Victory in Europe (especially Paris and Somerset, Spring 1945)

6. Occupational Therapy (Germany, 1945–1946)

Epilogue: Keeping Mum

Select Family Tree

Bibliography

Index

Acknowledgements

This book has been too many years in the making. There are many reasons for its long gestation. The best is that it was awaiting the opportunity for multi-media online publication that Open Book Publishers affords. Accordingly, my principal thanks are extended to Dr Alessandra Tosi, Director at OBP who has been a patient and sympathetic editor, and Annie Hine for her painstaking attention to detail and aesthetics. The personal assistance and encouragement of many others have influenced this project during its development. Special thanks go to Prof. Sue Harper, Prof. Karen Savage, Dr Malcolm Smith, Anne Springman, and my supportive colleagues at De Montfort University. I am also grateful for the attentive and kind services of the Association of Wrens, the D-Day Story, Portsmouth, the Churchill Archives Centre, Churchill College, Cambridge, the Imperial War Museum, London, the National Archives, London, the National Museum of the Royal Navy, Portsmouth, Richard Callaghan at the Royal Military Police Museum, Southwick, and the BBC WW2 People’s War project contributors, https://www.bbc.co.uk/history/ww2peopleswar/. Finally, for their kindness and generosity in allowing the use of family papers, I am indebted to Martin Bazeley and Southwick Revival, Bill and John Box, and Will Ramsay.

List of Figures and Videos

1.1

Film clip (0.51) from WRNS (dir. Ivan Moffat, Ministry of Information, November 1941). Film: IWM (UKY 344), courtesy of the Imperial War Museum, London. https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/fc9155f9

1.2

WRNS Recruitment Leaflet. Private papers of Miss J. S. B. Swete-Evans, Documents.14994, courtesy of the Imperial War Museum, London.

1.3

The Curriculum Vitae of Joan H. Prior, 1940. Private papers of Joan Halverson Smith.

1.4

Britannic Assurance Co. Ltd., Joan H. Prior, letter of appointment, 11 November 1940. Private papers of Joan Halverson Smith.

1.5

Letter from R.W. Wood, District Manager (Romford), Britannic Assurance Co. Ltd., to Miss. Joan H. Prior, 11 September 1942. Private papers of Joan Halverson Smith.

1.6

WRNS Service Record, Joan H. Prior, 41801. Private papers of Joan Halverson Smith.

1.7

The former WRNS Training Depot at Mill Hill shortly after its opening as the Headquarters of the Medical Research Council in 1950. Image courtesy of Associated Press/Alamy Stock Photo. https://www.alamy.com/medicines-back-room-boys-in-their-new-headquarters-at-mill-hill-london-on-march-21-1950-having-waited-ten-years-for-it-to-be-opened-due-to-the-war-the-building-was-used-by-the-admiralty-during-the-war-as-a-training-centre-for-wrns-the-exterior-of-the-new-building-which-will-house-the-research-workers-in-their-experiments-and-tests-ap-photo-image519356228.html

1.8

Notes on Naval Abbreviations taken by Joan Prior on 21 September 1942 during her first week of basic training at Mill Hill (HMS Pembroke III). Private papers of Joan Halverson Smith.

1.9

Film clip (00.22) from The Vital Link: The Wrens of the Allied Naval Command Expeditionary Force, 1943-45 (dir. Chris Howard-Bailey, Royal Naval Museum, VHS recording, col., sound, 1994), courtesy of National Museum of the Royal Navy, Portsmouth. ©National Museum of the Royal Navy. https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/1979f4dc

1.10

Drawing of Norfolk House, St James’s Square, by Elspeth Shuter. Private papers of Miss E. Shuter, Documents.13454_000010, courtesy of the Imperial War Museum, London.

1.11

A sketch of the Registry, ground floor, Norfolk House, St James’s Square, by Jean Gordon. The D-Day Story Collection, 1986/227, courtesy of The D-Day Story, Portsmouth. © Portsmouth City Council. https://theddaystory.com/ElasticSearch/?si_elastic_detail=PORMG%20:%201986/227&highlight_term=Jean%20Gordon

1.12

‘New Year’s Resolution Norfolk House, 1944’. An illustration by Elspeth Shuter. Private papers of Miss E. Shuter, Documents.13454_000012, courtesy of the Imperial War Museum, London.

2.1

Wrens of ANCXF at Southwick House, Summer 1944, by kind permission of Royal Military Police Museum, Southwick.

2.2

Birthday card from Tricia Hannington (Wren) to Joan Prior, Southwick Park, 24 May 1944. Private papers of Joan Halverson Smith.

2.3

Admiral Ramsay with General Eisenhower at Southwick House, June 1944. Private papers of Joan Halverson Smith.

2.4

‘Headquarters Room, Southwick Park, Portsmouth, June 1944’, watercolour by Barnett Freedman, IWM_ART_LD_004638, courtesy of the Imperial War Museum, London. https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/10043

2.5

D-Day Wall Map, Operations Room, Southwick House, NMRN 2017/106/379, courtesy of National Museum of the Royal Navy, Portsmouth. ©National Museum of the Royal Navy.

2.6

‘Si Vis Pacem Para Wren’, poem by J.E.F., 2 June 1944, signed by Wrens of ANCXF at Southwick Park. Private papers of Joan Halverson Smith.

2.7

Illustration of Hut 113 by Elspeth Shuter. Private papers of Miss E. Shuter, Documents.13454_000019, courtesy of the Imperial War Museum, London.

3.1

Order from Director of WRNS to J. S. B. Swete-Evans (2/O Wren), 16 August 1944. Private papers of Miss J. S. B. Swete-Evans, Documents.14994, courtesy of the Imperial War Museum, London.

3.2

Contemporary newspaper reports of Wrens embarking for duty in France. Private papers of Miss J. S. B. Swete-Evans, Documents.14994, courtesy of the Imperial War Museum, London.

3.3

Wren officers departing for France, September 1944. Private papers of Miss J. S. B. Swete-Evans, Documents.14994, courtesy of the Imperial War Museum, London.

3.4

Wrens boarding an LSI, September 1944. Private papers of Miss J. S. B. Swete-Evans, Documents.14994, courtesy of the Imperial War Museum, London.

3.5

Wrens on deck, travelling to France, September 1944. Private papers of Miss J. S. B. Swete-Evans, Documents.14994, courtesy of the Imperial War Museum, London.

3.6

Wrens of ANCXF on board an LCI preparing to land at Arromanches, 8 September 1944. Private papers of Joan Halverson Smith.

3.7

Photograph of Saint-Lô, September 1944. Private papers of Miss E. Shuter, Documents.13454_000026, courtesy of the Imperial War Museum, London.

3.8.

Postcard of the gateway to the Hauteville, Granville. Private papers of Joan Halverson Smith.

3.9

View of the Wrens’ quarters (left) and barracks (distance) on le Roc de Granville. Private papers of Joan Halverson Smith.

3.10.

Postcard of The Casino at Granville, in pre-war days. Private papers of Joan Halverson Smith.

3.11

‘The local people began to trickle back, their possessions piled high on handcarts’. Private papers of Mrs B.E. Buckley, HU_099996, courtesy of the Imperial War Museum, London.

3.12

‘The local people began to trickle back, their possessions piled high on handcarts’. Private papers of Mrs B. E. Buckley, HU_099995, courtesy of the Imperial War Museum, London.

3.13

‘Granville from the window’, sketch by Elspeth Shuter. Private papers of Miss E. Shuter, Documents.13454_000032, courtesy of the Imperial War Museum, London.

3.14

Panel 30, The Struggle for Caen, Overlord Embroidery, courtesy of The D-Day Story, Portsmouth. © Portsmouth City Council.

3.15

Postcard of the beach and promenade, Granville (sent home by Joan Prior from St Germain-en-Laye). Private Papers of Joan Halverson Smith.

4.1

Postcard of the Eiffel Tower, Paris. Private papers of Joan Halverson Smith.

4.2

Château d’Hennemont, St Germain-en-Laye, May 1945. ‘With the British Navy in Paris. 12 and 13 May 1945, at the Headquarters of the Allied Naval Commander Expeditionary Force at St Germain-en-Laye’, Lieutenant E. A. Zimmerman, A_028586, courtesy of the Imperial War Museum, London. https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205159929

4.3

Entrance to Le Petit Celle St Cloud, Bougival, Autumn 1944. Private Papers of Mrs B.E. Buckley, HU_099999, courtesy of the Imperial War Museum, London.

4.4

Montage of souvenir photo packs (90x70mm). Private papers of Joan Halverson Smith.

4.5

George Mellor, RM (studio portrait, St Germain-en-Laye, 1944). Private papers of Joan Halverson Smith.

4.6

Joan Prior (studio portrait, St Germain-en-Laye, October 1944). Private papers of Joan Halverson Smith.

4.7

Forest of St Germain, Autumn 1944. Private Papers of Miss E. Shuter, Documents.13454_000041, courtesy of the Imperial War Museum, London.

4.8

Postcard of the Château St-Léger, Admiral Ramsay’s private residence. Private papers of Joan Halverson Smith.

4.9

Photograph taken by Phyllis ‘Ginge’ Thomas of Royal Marines parading through St Germain-en-Laye, Armistice Day 1944. ‘Ginge and I went out in front of the crowd and Ginge took two shots of them. Whether the snaps will come out or not we don’t know as they were moving all the time.’ Private papers of Joan Halverson Smith.

4.10.

‘Ginge’ Thomas and Joan Prior (studio portrait, St Germain-en-Laye, November 1944). ‘Ginge and I have had our photograph taken together and I’m sending one now in this letter, although we neither of us like it very much!’ Private papers of Joan Halverson Smith.

4.11

Postcard of Notre-Dame, Paris. Private papers of Joan Halverson Smith.

4.12.

Postcard of L’Arc de Triomphe de l’Étoile, Paris. Private papers of Joan Halverson Smith.

4.13

Postcard of the Théâtre de l’Opéra, Paris. Private papers of Joan Halverson Smith.

4.14

Postcard of Le Tombeau de Napoléon 1er aux Invalides, Paris. Private papers of Joan Halverson Smith.

4.15

Postcard of l’Église de la Madeleine, Paris. Private papers of Joan Halverson Smith.

4.16

Postcard of Le palais de Chaillot vu des jardins, Paris. Private papers of Joan Halverson Smith.

4.17

Postcard of La Place de la Bastille, Paris. Private papers of Joan Halverson Smith.

4.18

Menu for the dinner celebrating a football match between a team from the Royal Navy and the Sports Association of the 12th arrondissement, Paris, at the Vélodrome de Vincennes, 17 December 1944. Private papers of Joan Halverson Smith.

4.19

Postcard of La Place de la République, Paris. Private papers of Joan Halverson Smith.

4.20.

Photograph of ANCXF Wrens in the snow at Château d’Hennemont, December 1944. ‘Thank God we had all been issued with duffel coats!’ Private papers of Joan Halverson Smith.

4.21 & 4.22

Snowballing, Château d’Hennemont, Paris, Winter 1944. Photographs by Joan Prior. Private papers of Joan Halverson Smith.

4.23

‘Death of Admiral Ramsay’ (British Paramount News, b/w, mute, 02.10, 2 January 1945). Film: IWM (ADM 431), courtesy of Imperial War Museum, London. https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/bd9c2512

4.24

A guard of British, French and American seamen kept vigil in the Chapel, Château d’Hennemont, Paris, January 1945. Private papers of Miss E. Shuter, Documents.13454_000058, courtesy of Imperial War Museum, London.

4.25

‘Funeral of Admiral Ramsay’ (British Movietone News, b/w, mute, 04.19, 8 January 1945). Film: IWM (ADM 552), courtesy of the Imperial War Museum, London. https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/8155ffe5

4.26

Cover page of the order of the Funeral Service of Admiral Ramsay and his staff, 7 January 1945. Private papers of Miss E. Shuter, Documents.13454_000060, courtesy of the Imperial War Museum, London.

5.1

Order of Service for the Memorial Service of Admiral Sir Bertram Home Ramsay, Westminster Abbey, London, 8 January 1945. Private papers of Miss E. Shuter, Documents.13454_000063, by kind permission of W. Ramsay, courtesy of Imperial War Museum, London.

5.2

Pages from Joan Prior’s 1945 pocket diary. Private papers of Joan Halverson Smith.

5.3.

Leading Wren Tricia Hannington, BEM, St Germain-en-Laye, January 1945. Photograph by Joan Prior. Private papers of Joan Halverson Smith.

5.4

Target Shooting Card from Luna Park, 10 March 1945. Private papers of Joan Halverson Smith.

5.5

Art Spry, George Mellor, Stan Swann (RMs), Luna Park, Paris. Private papers of Joan Halverson Smith.

5.6

Margaret Beverley, ‘Ginge’ Thomas and Joan Prior, outside the guardhouse, Château d’Hennemont, St Germain-en-Laye, Spring 1945. Private papers of Joan Halverson Smith.

5.7.

Joan Prior and Margaret Beverley, St Germain-en-Laye, Spring 1945. Private papers of Joan Halverson Smith.

5.8

‘Ginge’ Thomas, Joan Prior, and Margaret Beverley, St Germain-en-Laye, Spring 1945. Private papers of Joan Halverson Smith.

5.9

Postcard of L’Arc de Triomphe, Paris. Private papers of Joan Halverson Smith.

5.10.

Postcard of L’Hôtel de Ville, Paris. Private papers of Joan Halverson Smith.

5.11

Postcard of Fontaine lumineuse, place de la Comédie-Française. Private papers of Joan Halverson Smith.

5.12

Postcard of Les Grandes Boulevards: Portes St Martin and St Denis, Paris. Private papers of Joan Halverson Smith.

5.13

Postcard of Notre-Dame, Paris. Private papers of Joan Halverson Smith.

5.14

Postcard of Place de l’Opéra, Paris. Private papers of Joan Halverson Smith.

5.15

The Château at Fontainebleau. Photograph by Joan Prior. Private papers of Joan Halverson Smith.

6.1–6.5

Minden, ‘one of Germany’s lesser-bombed towns’, 1945. Photographs by Joan Prior. Private papers of Joan Halverson Smith.

6.6 & 6.7

The Melitta factory, lately the Peschke air works, Minden, 1945. Private papers of Joan Halverson Smith.

6.8

View of the Quarterdeck from the office window, Minden, 1945. Photograph by Joan Prior. Private papers of Joan Halverson Smith.

6.9

The Quarterdeck, HMS Royal Henry, Minden, 1945. Photograph by Joan Prior. Private papers of Joan Halverson Smith.

6.10.

The perimeter gate, HMS Royal Henry, Minden, 1945.

6.11

Joan Prior before the Quarterdeck, HMS Royal Henry, Minden, 1945.

6.12

Mann’s Map of the Perimeter, Minden, 1945. Private papers of Miss J. S. B. Swete-Evans, Documents.14994, courtesy of the Imperial War Museum, London.

6.13 & 6.14

Wrens’ quarters, Wilhelm Strasse, Minden, 1945. Photograph by Joan Prior. Private papers of Joan Halverson Smith.

6.15

‘Washing day, Minden-style’, 1945. Photograph by Joan Prior. Private papers of Joan Halverson Smith.

6.16

Peschke Flugzeug-Werkstätten letterhead. Private papers of Joan Halverson Smith.

6.17

Kaiser Wilhelm-Denkmal, Porta Westfalica, 1945. Photograph by Joan Prior. Private papers of Joan Halverson Smith.

6.18

View of Porta Westfalica from Kaiser Wilhelm-Denkmal, 1945. Photograph by Joan Prior. Private papers of Joan Halverson Smith.

6.19

Postcard of Die Wittekindsburg, Porta Westfalica, 1945. Private papers of Joan Halverson Smith.

6.20.

Peschke Flugzeug-Werkstätten memo. Private papers of Joan Halverson Smith.

6.21

The Melitta factory swimming pool, Minden, 1945. Photograph by Joan Prior. Private papers of Joan Halverson Smith.

6.22

Joan Prior in the CO’s private pool, Minden, July 1945. Photograph by Kay Chandler. Private papers of Joan Halverson Smith.

6.23

Joan Prior at needlework in the CO’s garden, Minden, July 1945. Photograph by Kay Chandler. Private papers of Joan Halverson Smith.

6.24

Swimming gala at the Melitta pool, Minden, July 1945. Photograph by Joan Prior. Private papers of Joan Halverson Smith.

6.25

Gene, Eddie, Ted and the 4th man, Hamelin, July 1945. Photograph by Joan Prior. Private papers of Joan Halverson Smith.

6.26

The Class of ’45, HMS Royal Henry, Minden, 15 August 1945. The Best Years of Their Lives? Photograph by Joan Prior. Private papers of Joan Halverson Smith.

6.27

Blown railway bridge across the River Weser, Minden, 1945. Photograph by Joan Prior. Private papers of Joan Halverson Smith.

6.28

Damaged pontoon bridge across the flooded River Weser at Minden, 1945. Photograph by Joan Prior. Private papers of Joan Halverson Smith.

6.29.

Blown bridge across the River Weser, Minden, 1945. Photograph by Joan Prior. Private papers of Joan Halverson Smith.

6.30.

Joan Prior’s shorthand notebooks. Private papers of Joan Halverson Smith.

6.31

View from ‘the top of a terrific hill’ at Detmold, 1945. Photograph by Joan Prior. Private papers of Joan Halverson Smith.

6.32

‘House where we had tea at Detmold’, 1945. Photograph by Joan Prior. Private papers of Joan Halverson Smith.

6.33

View from above Bad Harzburg. Photograph by Joan Prior. Private papers of Joan Halverson Smith.

6.34

View in the Harz mountains, October 1945. Photograph by Joan Prior. Private papers of Joan Halverson Smith.

6.35

View from the ‘Sky-ride’, Harz Mountains, October 1945. Photograph by Joan Prior. Private papers of Joan Halverson Smith.

6.36–6.42

Minden street scenes, November 1945. Photographs by Joan Prior. Private papers of Joan Halverson Smith.

6.43–6.46

Four pages from JP’s diary covering her leave between 21 November and 9 December 1945. Private papers of Joan Halverson Smith.

6.47

Letter from Wren Enid Lovell to Joan Prior and ‘Ginge’ Thomas, 16 January 1946. Private papers of Joan Halverson Smith.

6.48

British Empire Medal, awarded to Leading Wren Joan Prior, December 1945. Private papers of Joan Halverson Smith.

6.49

Award Letter, 11 January 1946. Private papers ofJoan Halverson Smith.

6.50–6.52

Flooded countryside around Minden, February 1946. Photographs by Joan Prior. Private papers of Joan Halverson Smith.

6.53 & 6.54

Floods in Minden, February 1946. Photographs by Joan Prior. Private papers of Joan Halverson Smith.

6.55

Hand-painted Easter Card purchased in Minden. Private papers of Joan Halverson Smith.

6.56

Leading Wren J. H. Prior, 41801. Order for Release, 31 May 1946. Private papers of Joan Halverson Smith.

6.57

Letter from Betty Currie to Joan Prior, 19 March 1948. Private papers of Joan Halverson Smith.

6.58

Telegram from Ginge and Clark to Joan Prior, 24 April 1948. Private papers of Joan Halverson Smith.

6.59

WRNS Employment Certificate, 31 May 1946. Private papers of Joan Halverson Smith.

7.1

‘Keep Mum she’s not so dumb’, MOI Careless Talk Costs Lives campaign poster, 1942, INF 3/229, courtesy of The National Archives, London. https://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/C3454442.

7.2

A page from Joan Prior’s shorthand notebook. Private papers of Joan Halverson Smith.

The Wrennery

Ashton (Cartwright), Kathleen (Wren: Teleprinter Operator), 1923–2012.

Blandford, Patricia (2/O Wren: Telephonist).

Box (Shuter), Elspeth Joan, MBE (2/O Wren: Assistant Staff Officer Landing Craft), 1912–1979.

Buckley (Noverraz), Barbara Eileen (2/O Wren: Cypher Officer), 1919–2008.

Gordon (Irvine), Jean (Leading Wren: Writer), 1923–2002.

Howes (Mallett), Mabel Ena ‘Bobby’, BEM, Legion d’honneur (PO Wren: Telephonist), 1919–2019.

Hugill (Gore-Browne), Fanny, Legion d’honneur (3/O Wren: Writer), 1923–2023.

Mellor (Boothroyd), Margaret A. (Wren: Teleprinter Operator), 1923–1994.

Rahilly (Blows), Beryl K. (3/O Wren: Writer), 1922–2003.

Smith (Prior), Joan Halverson, BEM (Leading Wren: Writer), 1923–2021.

Swete-Evans, Janet Sheila Bertram (2/O Wren: Signals), 1889–1988.

Thomas, Phyllis ‘Ginge’, BEM (Leading Wren: Writer), 1919–2016.

A Note on the Presentation of Names

In the list above I have included in brackets the birthnames of the principal Wrens whose testimony forms the basis of this account and organised them by the married names they later adopted. Some, like ‘Bobby’ Howes, were married before they joined the WRNS. In textual citation I have used the name given in the archival source, which is reproduced in the Bibliography. I have avoided the use of the term née.

Prologue: Letters from an Unknown Woman

©2024 Justin Smith, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0430.00

For the WRNS in the Southern ports ‘D’ Day will be remembered as the culminating event of many years of hard work, for it was the invasion of the Continent that had always been the ultimate object, and before and during that historic occasion much was asked of the Wrens and much was given. (Admiral Sir William James, GCB, 1946)

1

I was driving down to Portsmouth to deliver my mother’s ashes to the Royal Naval Dockyard, two years after her death during the COVID pandemic. The day before I left would have been her one hundredth birthday, had she lived.

Now that the experience of military service in the Second World War is almost beyond living memory, all we have left is the archives. Of course, we’ve had them all along. And they have grown over the years as more official records (at The National Archives and the Imperial War Museum) have been opened, like unquiet graves, and the oral testimony of those dwindling survivors (occasioned by the significant anniversaries of recent decades) has accrued. There is the possibility, perhaps, of a kind of settlement with the past, once those who lived through it have departed.

Where the motorway approach to Portsea Island from Southampton ascends past Fareham and carves a channel under the chalk ridge of Portsdown Hill the landscape above still retains the surface features of a militarised zone—Fort Nelson, Fort Southwick, Fort Widley, Fort Purbrook—whose networks of subterranean tunnels and chambers extend deep inside the cliff. Here was the nerve-centre. And from atop the hill is where those off-duty watched anxiously and waited, overlooking the coastal map of harbours, creeks and inlets below blocked with a thrombosis of vessels. There are innocuous journeys it is impossible to make smoothly without ploughing through history. Digging up the past.

In this regard the Second World War is an overworked furrow. Like a popular footpath in a national park, we’re in danger of wearing it away. But we are exercised in part by the fear of forgetting the lessons of history, or of not learning them well enough. We have a responsibility to future generations, we tell ourselves. Never again. Remember, remember. The moral problem, in the face of all that sacrifice, is not ‘lest we forget’ but that we can never remember enough. Generation after generation, like good pilgrims, we follow the same uphill trek; every ten years or so we stop and turn back to review what is now far behind us, asking ourselves, ‘What does it look like from here?’.

My mother resisted all this, by and large—even when those compatriots from her service days succumbed to interviews, persuaded by researchers of ‘the people’s war’ (young enough to be their grandchildren) to disburden themselves of the loose change of memory, for the fiftieth, or the sixtieth, or the seventy-fifth commemoration. Her objection was founded on the oath she took on joining the Women’s Royal Naval Service: that she would disclose nothing of her wartime activities. Not even after hostilities had ended. Any secrets she possessed would go with her to the grave. If anything, this principle gained a stiffer hauteur over the years, as the tongues of her contemporaries wagged freely, popular histories abounded and television documentaries spilled the beans. On only one occasion did she lower her guard, for an oral history project to which she (and several friends) contributed both memories and memorabilia. The Vital Link: The Wrens of the Allied Naval Command Expeditionary Force, 1943–45, was released as a VHS recording, produced by the Royal Naval Museum in 1994, for the fiftieth anniversary of D-Day.2 I think because this was done under the auspices of the Navy, she thought it carried the seal of approval. All above board. I came across this tape together with a cache of letters, photographs and service documents and a couple of pocket diaries, when going through her things. Watching the video (recorded voices over rostrum camera shots of old black and white photographs and papers) revealed little more than the arc of their journey, this small band of Wrens—how they lived together, and something of what they recalled feeling at the time. But presumably my mother was satisfied that they hadn’t given much away. Even as a tribute this is cursory.

Women who served in World War II have also contributed (albeit marginally) to the vast array of literature commemorating D-Day (the most documented action of the entire war), and (substantially) to significant archives. Two Wrens who served with the Allied Naval Commander Expeditionary Force (ANCXF)—Petty Officer Mabel ‘Bobby’ Howes and Leading Wren Jean Gordon—are both cited in Frank and Joan Shaw’s We Remember D-Day (1994) and, ten years later, in Martin W. Bowman’s Remembering D-Day: Personal Histories of Everyday Heroes (2004). Gordon also featured in The Vital Link and deposited her own testimony at the D-Day Museum archive in Southsea. Howes was one of a number of Wrens who contributed to the BBC’s People’s War memory project (2003–2006) which formed part of the sixtieth anniversary commemorative histories. This admirable venture, which garnered ‘over 47,000 stories and 14,000 images’,3 included testimony from former ANCXF Wrens Margaret Boothroyd, Kathleen Cartwright and Phyllis ‘Ginge’ Thomas (who were stationed at Southwick Park, near Fareham on D-Day), and Elsie Campbell who was a Watchkeeper in the Signals Distribution Office underground at nearby Fort Southwick. Ginge Thomas (1919–2016), who worked for the Chief of Staff to the Supreme Allied Commander (designate) (COSSAC) before joining ANCXF, also contributed to The Vital Link and was interviewed by Rachel Vogeleisen for Women Who Served in World War II: In their own words (Mereo, 2020). It is ironic perhaps, given my mother’s tight-lipped stance, that her best Wren friend should have been so vocal in her later years. But she would probably say, ‘You never could get a word in edgeways with Ginge’. At any rate, I’m grateful for her testimony, not least because she is the only source to mention my mother by name: ‘I have a very clear memory of sitting in the back of a lorry with my friend Joan Prior, holding on to our typewriters and duplicators, on the way to Southwick’.4 As the following pages will reveal, theirs was a special wartime relationship.

There are twelve disciples in this history and I have so far introduced six: Howes, Gordon, Boothroyd, Cartwright, Thomas and Prior; all ratings, with the exception of Petty Officer Howes. Besides Gordon, the D-Day Museum archive also holds transcripts of oral history interviews with Third Officer Beryl K. Blows and Second Officer Patricia Blandford. It seems that Blandford later wrote an entire dissertation entitled ‘Fort Southwick: What Useful Purpose Did It Serve?’. Extracts from this are cited as ‘A Wren’s Tale’ in Geoffrey O’Connell’s local history, Southwick, The D-Day Village That Went to War (1995). The remaining four women were also officers: Fanny Hugill (Gore-Browne) (3/O), Elspeth Shuter (2/O), Barbara Buckley (Noverraz) (2/O) and Sheila Swete-Evans (2/O). Fanny Hugill gave a rich personal tribute to the Allied Naval Commander Expeditionary Force himself, Admiral Sir Bertram Home Ramsay, on the occasion of a symposium to mark the donation of his personal papers to the archives of Churchill College, Cambridge, on 6 June 2014.5 It is not difficult to discern from her words the enduring devotion of these women, proud to be remembered as Ramsay’s Wrens. Hugill, who died on 28 September 2023 at the age of 100, is believed to have been their last.6Shuter, Buckley and Swete-Evans each leave legacies of different kinds at the Imperial War Museum in London. Swete-Evans’ papers include printed orders and photographs of Wrens embarking for Normandy in September 1944. Buckley has some remarkable photographs taken in France later that year. Shuter, an art teacher pre-war and a close friend of Buckley (Noverraz), bequeathed (amongst other papers, photographs and sketches) the most substantial written account of all: a 156-page memoir of her service from the time she joined ANCXF from Combined Operations in 1943, where she served until April 1945 when she was admitted to the Senior Naval Staff course at the Royal Naval Staff College, Greenwich. She served as Assistant Staff Officer Landing Craft and frequently deputised for the Commander, Staff Officer Landing Craft, and represented the ANCXF at meetings of SHAEF,7 reporting on the supply and distribution of landing craft. For the last few months of her service in France she was also ANCXF’s official war diarist.

These are the twelve principal sources from whom this history is drawn. If they provide a chorus of voices, in which the soloists Elspeth Shuter and Joan Prior share a platform, together they comprise three of what Penny Summerfield identifies as the ‘four genres of personal testimony: letters; diaries; memoirs; and oral history’.8 Joan Prior’s diaries are insubstantial as sources (small pocket-diaries used for incidental dates, personal reminders, birthdays and the titles of films seen). She didn’t have the discipline to keep a journal. Her writing is public and familial, not private and personal. Nothing confessional. But I have included visual sources from my mother’s papers (and other archives) including photographs and service documents where appropriate. Online publication also allows for the sparing use of sound and moving image clips. How do audio-visual sources augment the written testimony? Or, as Annette Kuhn frames the question, ‘what place do images and sounds occupy in the activity of remembering?’9 The photographs, in the main, accompany the overseas travels of ANCXF in Parts II and III. Photography, for security reasons, was forbidden on UK military bases. But, from their departure for Normandy in September 1944, a visual travelogue ensues, itself an expression (as well as a documentary record) of liberation. There is portraiture too (in studios and on location), which was as popular in those times as the modern ‘selfie’ and as necessary an accompaniment to communication as the letters that carried them. My mother was also an inveterate collector of postcards on her travels (sometimes written and sent, often not), many of which augment her own ‘snaps’. Archival film and audio testimony have been used sparingly as clips to provide points of contextual anchorage. But they also conjure the past differently from words on the page; they hail us in more romantic languages.

Although I have consulted a number of histories of D-Day, including the substantive contemporary accounts of those commanders most closely involved, I have made only minimal use of these published sources for three reasons which may appear at first sight to be contradictory. Firstly, this is a history of the Wrens of ANCXF and, as far as possible, I want their words to tell their own story. Secondly, this isn’t really a military history at all, in the political sense. Those accounts have already been written, exhaustively. It is rather a women’s history of military service. But it makes a modest, revisionist claim that military history should also incorporate experiences such as are gathered here. Thirdly, the substantial archive of my mother’s letters home, which take centre stage in the second half of this book, requires the establishing context that her peers provide in the first half. Locating her subjective, contemporary responses in this way is important to understanding how, like all service personnel, she was both typical and exceptional. In this sense the book reverses the coordinates of standard historical methods. I am not using personal testimony and archival sources as evidence to support a historical account. Rather, I am using primary and secondary texts—augmented in places by semi-fictional narrative—to frame the presentation and aid the interpretation of a central archive comprising my mother’s letters, photographs, documents and diaries. Where there are gaps in her correspondence, I have tried to fill them imaginatively, but not, it is hoped, too intrusively. These personal acts of interpolation became another means by which I could begin to make sense of the accidental archive she had left.

Letters home in wartime provide mercurial evidence. On the one hand, as personal records of the excitements and the strictures of daily military life for eager but unwitting young volunteers, they offer a rich tapestry of travels and travails. On the other hand, what they reveal of their part in the conflict is limited both by their author’s subaltern and marginal role, and by (self-)censorship. Their preoccupation with the quotidian often misses the bigger picture. And the extent to which the personal accounts of individuals can be read as representative of the group is difficult to judge from a single source. In this way, the subjectivity, immediacy and temporal redundancy of letters render their historical value always contingent, set in a continuous provisional present. Using them as historical artefacts broaches a fundamental contradiction. Like newspapers and mayflies, they live for a day.

In Epistolarity: Approaches to a Form, Janet Gurkin Altman writes that ‘in numerous instances the basic formal and functional characteristics of the letter, far from being merely ornamental, significantly influence the way meaning is consciously and unconsciously constructed by writers and readers of epistolary works’.10 This is undoubtedly true also of non-fictional correspondence, especially that conducted in wartime. For the writer is always conscious of the impersonality of the military sorting office (in this case frequently Base Fleet Mail Office) that must be written at the top of the first page. And for Joan Prior, like many correspondents whose war work was desk-based, the omnipresent typewriter made personal letter-writing easy to do (between jobs), but also thereby an extension of their work. Frivolous and quotidian though much of my mother’s narrative may be, it constrains intimacy with the more formal stance of reportage.

Finally, letters home also, inevitably, spend a good deal of time addressing the absent family and their affairs. There is a self-conscious discipline in Joan Prior’s letters of replying to the last letter received. Since the family situation is unknown (and probably uninteresting) to the general reader, and only one side of the correspondence survives, footnotes attempt to identify most individuals named and illuminate some of the circumstances referred to, where known. Indeed, because it is invariably one-sided, correspondence always reminds us of what is missing, its untold other to whom it constantly refers. It follows that my mother’s letters are also family history. They construct the family and bind it together. But they do so by reproducing an imagined fantasy of home—an important creative purpose for many young servicemen and women enforced to spend miles and years away from home. Jenny Hartley writes, as ‘fictions of contact and spontaneity, women’s wartime letters are masterpieces of simulated conversation’.11 She might have been talking about my mother. Yet at the same time, letters are always as significant for what they withhold. Between the lines they are riddled with secrets and omissions, gaps in the evidence. Secrets are also a formal property of the letter, a form which simultaneously withholds as much as it discloses. This includes not only what was not allowed to be said about the war, but what couldn’t be said in the family either.

But what follows is not only a one-sided conversation with two different parties, her parents (Grace and Harry Prior) and her elder sister Bessie and brother-in-law Stan; Joan Prior’s letters are also unevenly distributed across her military service. There are no letters written home while she was undergoing basic training at Mill Hill, or while stationed at Norfolk House between September 1943 and April 1944. After all, for East Enders, London was hardly away from home at all. The first correspondence dates from the time between April and September 1944, when Joan was with the Allied Naval Commander-in-Chief Expeditionary Force (ANXCF) at Southwick Park in Hampshire. Yet only three letters (written in May and June 1944) survive from this period. In fact, it is not until the Wrens of ANXCF landed in Normandy, in September 1944, that Joan’s regular letters were kept by her parents. This pattern is an indication of two things. Firstly, self-censorship and the secrecy of the pre-invasion planning is likely to have made letters home rarer before June 1944. But secondly, and more obviously, it was not until Joan was overseas that correspondence became such an important lifeline for both parties, and that her experiences became more newsworthy and therefore worth keeping. Indeed, the fact that Joan requests her parents keep the letters and postcards she sends from France and Germany suggests that ordinarily they might not have done so (and that therefore earlier correspondence dating from her home service can be assumed to have been lost). Furthermore, it shows that Joan was consciously making a record of her experience overseas not merely for her family but for posterity.

In her introduction to Women’s Letters in Wartime, Eva Figes writes:

I have […] followed a policy of publishing letters in their entirety or not at all […] I have to admit that a trail of dots in any published book always leaves me full of frustrated curiosity. War is not experienced in isolation. Usually it goes on for months or years, and gets bound up with our ordinary lives, one way or another.

12

In the epistolary narrative which dominates the second half of this book, I have adopted a similar, unfiltered approach, not for fear of frustrating the reader’s curiosity (for repetition is as tedious as excision), but out of respect for the integrity of the archive, and its author. Only occasionally have overlaps between the letters to Joan Prior’s parents and sister been omitted, where duplication is most prominent. But there are two subjectivities in play here: hers and mine. In creating a narrative from the archive, I want to recover her story. But in that act of commemoration, I am also telling a story about her (which is my own).13

Eva Figes is not alone in noting the selectivity evident in the collections of the Imperial War Museum: ‘people tended to think letters interesting and worth preserving if they were written by women away from home and doing active service of some kind. […] This bias reflects the proud perception of the recipient, usually a parent […] that the person who wrote the letters is doing sterling service for her country’.14On a practical level, this is true enough. But it is worth reflecting further on the status of the letter as a particular kind of human transaction.

Kafka observes that:

The great feasibility of letter writing must have produced—from a purely theoretical point of view—a terrible dislocation of souls in the world. It is truly a communication with spectres, not only with the spectre of the addressee but also with one’s own phantom, which evolves underneath one’s own hand in the very letter one is writing or even in a series of letters, where one letter reinforces the other and can refer to it as a witness.

15

This observation has been pursued in a variety of settings by historians of the letter. For Penny Summerfield, Dena Goodman ‘writes of letters as a medium through which women produced and consumed stories about themselves in the past, and letter writing as a process of self-discovery that facilitated the development of a “culture of the self”’.16Antoinette Burton ‘explores the personal narratives of three Indian travellers to Britain between 1880 and 1900. […] Cornelia Sorabjii, one of the three, travelled from Poona in India to England in 1889, to study at Oxford University’. For Burton, ‘her letters home were […] a stage on which she “performed” for her parents, explaining her choices, describing her social interactions, and testing her own respectability and moral worth against their values’.17David Gerber describes another aspect of the correspondent’s mode of address as the ‘“epistolary masquerade” in which letter writers adopt strategies of communication designed to maintain and develop key relationships while placing limits on self-revelation’.18

These dynamics are all in play to some extent in my mother’s wartime correspondence. And although the self as presented in her letters cannot be read as representative of the Wrens who were her comrades and friends, the inherent subjectivity of her evidence is of historical value precisely because, as Summerfield concludes, ‘the epistolary self is regarded as both an agent of change and a prism through which the social, cultural and psychic dynamics of history may be understood’.19

The value which Summerfield attributes to the letter writer as a source of historical evidence must be weighed against Eva Figes’s caution: ‘many letters written by ordinary people, undistinguished by rank or accomplishment, and sent for mundane reasons, can be very tedious to the snooping eyes of posterity’. For Figes, ‘perhaps only love and war can raise the temperature of life sufficiently to give real life and interest to letters written by lost generations, and the vicissitudes of war have more infinite variety than even the most consuming passions’. As it is hoped for the case of the archive presented in this book, ‘War letters are fascinating because they tell us of great historic events seen at ground level, from an individual point of view’.20

Tamasin Day-Lewis puts this historical enterprise into another perspective: ‘on the whole, we are no longer letter-writers. Telephones, faxes and email have radically changed the part that letters used to play in people’s lives.21 Even this statement, from a book published in 1995, now sounds dated. But paradoxically, this technological transformation has recuperated letters as a unique medium of historical value, like shellacs in the age of Spotify.

For Day-Lewis, ‘many of the people who lived through the Second World War describe it as the most exciting and dynamic period of their lives’.22 My mother never said this. If anything, she downplayed it. But it was undoubtedly true, as her letters bear witness. I have often wondered if that was subsequently a source of disappointment to her, and many like her. She never admitted that either.

For me, this discrepancy, imagined perhaps, is part of a deeper disjunction which my mother’s archive opens up. In the account which follows I have had to adopt a series of trade-offs: firstly, between the individual life in the letters and the context of the surrounding memory work gathered from a variety of sources; secondly, between family history and military history; and thirdly, between the desire to transcribe the letters verbatim in their entirety for the sake of archival integrity, and the temptation to edit and interpret them for narrative motives. The compromise I have arrived at has been fuelled by two further, personal obsessions: that I would find some explanation in the letters for the idiosyncratic front of secrecy she maintained for the rest of her life; and that I might meet the young woman who later became my mother, this stranger who seems like someone I should know.

PART I

Overlord Embroidery

1. Wrens’ Calling (London, 1942–1944)

©2024 Justin Smith, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0430.01

The National Services (No. 2) Act of December 1941 was the first to conscript unmarried women between the ages of twenty and forty (later nineteen and forty-three) to undertake work in the war effort: in industry, agriculture or one of the uniformed services. Hannah Roberts writes that:

Early objections to the conscription of women gave way to a national sentiment that was overwhelmingly positive. […] Women who entered the women’s services were far from derided; instead, they were congratulated for doing so. […] Patriotism had a great impact upon all of the women’s services, which began to grow rapidly after 1941. Numbers of Wrens doubled between 1941 and 1942.

23

Unlike the other women’s services, the WRNS did not take conscripts; volunteers went through a selection process. There was a widespread assumption (shared by many who applied and indeed their parents) that social class was a determining factor in vetting applicants.

Jean Gordonreflects:

For girls of my generation and background, who were not normally encouraged or expected to go to work in the way everyone does now, and therefore not encouraged to train for anything useful, the war was an opportunity for them to leave home, gain some sort of independence and do something interesting which was actually approved of by their “elders and betters”. Mothers of those days who would not have allowed their daughters to work in “unsuitable” occupations and had them chaperoned and constrained with, to us now absurd restrictions, thankfully allowed themselves to trust in the universally held belief that all would be safe in the gentlemanly embrace of the Royal Navy. And in this they were proved to be right, as a matter of fact.

24

Another Wren, Audrey Johnson, recalls: ‘my mother had not wanted me to join the Land Army, because it would ruin my hands, neither had she wanted me to go into a munitions factory because she did not think I would like the type of woman there’. Such prejudices were widespread. Johnson confided to a friend, ‘If I joined anything it would be the WRNS. It’s the most difficult service to get into’. Furthermore, by aiming high, ‘if we were turned down for the Senior Service we could still apply for the WAAF, and if that failed there was always the ATS’. Despite her expectations of failure, Audrey, ‘the stepdaughter of a foreman engineer from Leicester’, was enrolled as a Wireless Telegraphist. Nonetheless, in her new environment she:

felt unsure, lonely and out of place and could not work out how I had been accepted for this service, that appeared to choose its entrants with such care. I had nothing they asked for, certainly no educational qualifications. I had a feeling I must be the only girl who had left school at fourteen. But I was not going to mention that to anyone, and night school elocution lessons had helped a bit.

25

The example of Audrey Johnson shows that neither background nor qualifications were a barrier to her joining the Wrens, although aspirational ‘self-improvement’ may have played a part.

As Jeremy Crang writes:

In order to ensure that the ATS (and in time the WAAF) got the necessary recruits, it was made clear that women would be allocated according to ‘the needs of the services’. To help facilitate this process, special entry requirements were laid down for the WRNS (which had a long waiting list for voluntary applicants). These were designed to ensure that a large proportion of optants would be ineligible for the Wrens and included proficiency in German, practical experience of working with boats, or a family connection with the Royal or Merchant Navy.

26

Although the WRNS remained the smallest of the three uniformed women’s services, as Audrey Johnson and countless other examples show, in practice these criteria, if relevant at all, were only loosely applied. Nonetheless, the Ministry of Information (MOI) recruitment film WRNS (dir. Ivan Moffat, November 1941) presents initiation into the service from the perspective of the officer-class, fresh from Greenwich training college, but endowed with plenty of paternal Naval pedigree.27

Video 1.1. Film clip (0.51) from WRNS (dir. Ivan Moffat, Ministry of Information, November 1941). Film: IWM (UKY 344), courtesy of the Imperial War Museum, London.https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/fc9155f9

Far from putting off applicants from humbler backgrounds, who like Audrey Johnson didn’t obviously belong to the Naval ‘club’ through family connections, recruitment films encouraged aspirational applicants. In some senses joining the services may have offered many young women, Joan Prior included, a fast-track to social mobility. Brenda Birney, ‘not having any affiliation with any particular Service’, decided like Audrey Johnson ‘to apply first to the WRNS and if they refused me I’d try the WAAF, leaving the ATS till the last. […] I was called for an interview for the WRNS when I was asked if I had any particular reason for wanting to join them. It didn’t occur to me that the correct answer to this was that my father, uncle or whoever, was an admiral, although this did cross my mind much later’.28Birney’s recent office work experience meant she was chosen to be a Writer. Like many others of her background, on arriving at the training depot at Westfield College, Hampstead,29 she decided ‘It was the nearest I was ever to get to going to university. […] I was the best in the writers’ class. […] They looked on this as a crash course from which we would emerge after three weeks as fully fledged secretaries’.30

Of one of her interviewees, Barbara Wilson, Penny Summerfield reports: ‘as a middle-class young woman, she decided that she would have to join the WRNS, the most socially select of the available options’.31 Whilst Roberts’ evidence substantiates this perception ‘that the WRNS was the most admired’ of the women’s uniformed services, and ‘far more selective than the ATS’, she insists ‘this was based on the skills and abilities of the applicants, rather than their family backgrounds or social contacts’.32

Alongside a rapid increase in its recruitment, the period of 1941–1942 also saw an expansion of the roles women could perform in the Wrens. At the outbreak of war, ‘the WRNS was organised into two categories: one was “specialised branch”, which would cover office duties, motor transport and cooks; the other was “general duties branch”, for stewards, storekeepers and messengers’.33 By 1942, the quest to relieve as many men as possible from shore-based roles to serve at sea led Wrens to be trained in a range of highly-skilled tasks—some of which, such as Anti-Aircraft Target Operators were semi-combatant. Wrens became Air Mechanics, Torpedomen, Ordnance (Armourers), Radio Mechanics, Degaussing Recorders, Dispatch Riders, and ‘the most popular and symbolic of the WRNS categories’: Boats Crew.34 Wrens were also employed as Coders, Telegraphists, Cyphers, Signallers and Plotters.

Although Wrens could in theory choose a role, they were in practice directed according to the selection evaluation and the needs of the service. Priscilla Hext (Holman) ‘applied to join Boats Crew, but alas that category was full up. They offered several jobs, but none appealed so they gave me an aptitude test. […] Next day I was sent to see a Lieutenant Commander Royal Navy who told me that the test showed I had an engineering aptitude, so would I like to join the Fleet Air Arm as an Armourer?’.35Roberts’ interviewee, Sheila Rodman, had worked as a ‘laboratory assistant and typist for James Neelam and Co. steelworks’ in her native Sheffield. Like Hext, she ‘was selected to train as a Wren Ordinance (Armourer)’ in the Fleet Air Arm.36 Hazel Russell (Hough) was:

a fully trained secretary, employed by an insurance company. In my spare time I drove a YMCA van to anti-aircraft gun and balloon defence sites in the north London area. Since I wanted to join the Services I decided to volunteer to join the WRNS and hoped that I could become a driver. […] I was then given a driving test and to my surprise was told that I had failed and they tried to persuade me to become a typist […] Fortunately they were considering the possibility of recruiting six Wrens’ […] [at]

HMS

Dolphin

, the submarine base in Portsmouth harbour […] to replace the sailors who manned […] a simulator known as the Attack Teacher.

37

She was accepted, promoted to Leading Wren and ran an Officer training programme in submarine attack, conducting maintenance of the simulator between courses.

Understandably much attention has been paid by writers like Summerfield and Roberts to the examples of women working in masculine roles during World War II, the contingent nature of this permission to transgress gendered occupations, their experiences of those freedoms, their limitations and risks, and the reactions from co-workers and family members. Indeed, interest in this phenomenon was manifest and widely publicised at the time, in the press, in MOI propaganda, in books and in films such as Millions Like Us and The Gentle Sex (both 1943). Peggy Scott’s 1944 celebration of female contributions to the war effort, They Made Invasion Possible trumpets: ‘they have taken over the men’s jobs in the Services, in the factories and the shipyards, on the railways and the buses, on the roads and on the land’.38 And her Wren examples feature Boats Crew, ‘the first woman Fleet Mail Officer’, Plotters, Wren Torpedo-Men (sic) and Signallers. Less attention is paid, then and now, to trained clerks and secretaries who served as Writers and Telegraphers in the WRNS. But for all those, like Brenda Birney and Joan Prior, whose work experience led them to become Writers, there are others whose potential to exceed their peacetime lot was identified in selection.

Roberts writes of Daphne Coyne, who ‘was discouraged from going to the WAAF recruiting office by her mother because the WRNS was seen as “THE service”’.39 Yet she:

came from a single parent family and had been working in a nursing home as a cook before joining the Wrens in 1940. Her expectation when going for interview was that she would become a cook or steward, as these were the only categories open at the time and mirrored her work experience. However, after beginning work as a messenger in a cypher/signals office she became one of the first Wrens trained to interpret radar signals. Clearly, the WRNS was more concerned about the ability of the people it employed than their social background.

40

As Summerfield’s extensive oral history work demonstrates, family background and parental opinion were significant factors in shaping young women’s service aspirations. Yet her findings show ‘there were no simple determinants’—such as social class or the daughter’s/parents’ ages—on these decisions. Summerfield’s nuanced interpretation of her interviewees’ testimonies reveals ‘the process by which women’s family narratives positioned the self in relation to discursive constructions of wartime possibilities for young women. It reveals what different positions meant for the identity “daughter”.41 For Crang what underpinned these negotiations was a seismic disruption whereby pre-war concepts of the “dutiful daughter” clashed with wartime notions of the independent young woman serving the state’.42

Fig. 1.2. WRNS Recruitment Leaflet, private papers of Miss J. S. B. Swete-Evans, Documents.14994, courtesy of the Imperial War Museum, London..

In order to understand how this sociological tension played out in the case of my mother, it is necessary to know something of her own family background. Joan Prior was born in Barking, Essex, on 24 May (then Empire Day) 1923. The youngest of the three surviving daughters of a retired brewer, Henry (Harry) Prior, and his wife Grace, Joan had the advantage of a private education over her elder sisters, Grace (called Geg) (1908–1992) and Bessie (1909–1984). Fourteen years separated Joan from her next sister Bessie; there were but seventeen months between Bess and Grace. Her elder sisters not only grew up side by side, and went to the same schools, but were married on the same day, 22 July 1933, the year of Hitler’s rise to power in Germany. As it happened, the occasion was more precipitous for the Prior family. A double wedding had been planned between the sisters, but their mother Grace, superstitious to a fault, rejected the idea as unlucky. So, they were married on the same day, at the same church, St Margaret’s Barking, two hours apart. Grace first, to Charles Snell; then Bessie, to Stanley Bones. The day went off without a hitch, much to everyone’s relief. Then, a month later, on 24 August, tragedy struck the Bones family. The husband of Stan’s elder sister Annie, John Spink, was killed in an accident at work. He was employed by Nicholson’s Gin-makers at their Three Mills distillery, Bromley-by-Bow. According to local newspaper reports, during a spell of hot weather he had been swimming in one of the large water tanks at the site and drowned. The inquest jury returned a verdict of death by misadventure. Grace Prior’s verdict was characteristic: ‘thank God we didn’t have that double wedding, or they’d have blamed us!’

This anecdote is instructive of the family’s mental landscape, dominated as it was by the paranoid fears of their mother. But it wasn’t that she didn’t have cause for anxiety. Grace and Harry Prior had lost their first-born daughter, Winnie (b. 1905), to rheumatic fever at the age of eleven in 1917. Beyond their grief at burying a child blooming with life in Rippleside cemetery, life (and death) went on: the end of the Great War brought the Spanish flu. With two other daughters under ten, a household to run and a husband working (and drinking) all hours at Glenny’s Brewery, Grace Prior soldiered on as best she could. But in 1921 the trauma surfaced and she broke down. The doctor advised Harry Prior they should try for another child: a replacement. Joan was born a fortnight before her mother’s fortieth birthday and was immediately doted upon. Within a couple of years her elder sisters, both good at arithmetic, left school and found employment: Geg became a cashier at Bright’s butchers in Barking, Bess a ledger keeper at Eastick’s in the City. By the time Joan was ten, her sisters were married. Their mother could lavish all her attention on Joan. And she did.

If this sketch provides an idea of the family’s emotional temperature, the second factor that is important is their social position. As the depression hit Britain in 1930, the Priors’ lives changed. Harry Prior, following in his father’s footsteps, had risen from drayman’s boy (at fourteen) to head brewer at Glenny’s on a decent wage. But at the end of 1929 the company announced a takeover by Taylor, Walker & Co. Ltd, with the sale of fifteen pubs in Barking, Dagenham and Romford and the closure of the Linton Road brewery. There were thirty employees, nearly all of the older ones like Harry Prior (approaching fifty) being shareholders, and they were assured of ‘just and generous compensation’.43 The Priors invested this money into a succession of moderately unsuccessful small businesses, including corner shops and tobacconists in Barking, Walthamstow, Chadwell Heath and Hornchurch. They also funded their sons-in-law, Charlie Snell (an electrician) and Stan Bones (a haulage driver), to buy a garage—an enterprise which fell through. Despite their lack of entrepreneurial acumen, the family could afford annual holidays (to the West Country and the Isle of Wight) and, from the age of eight, to educate Joan privately, at Napier College, Woodford. These aspirations were entirely in keeping with their resolutely Conservative politics. During the school summer holidays in the early thirties, Joan would be sent away on the Great Western Railway from Paddington to Cardiff, where she stayed with Aunt Lucy (Grace Prior’s sister-in-law) and her daughter Peggy, ten years Joan’s senior. It was always said this was to give Aunt Grace ‘a break’.44

Fig. 1.3. The Curriculum Vitae of Joan H. Prior, 1940. Private papers of Joan Halverson Smith.

When she left Napier in 1939, Joan completed a year-long shorthand-typing course at Pitman’s Secretarial College at Forest Gate from which she obtained excellent certificates of proficiency. By then war had come. Joan initially found employment with an insurance company at Regis House, King William Street, on the north side of London Bridge. But in the full force of the Blitz in the late Summer of 1940 the daily commute had become increasingly perilous. Despite the large air-raid shelters under Regis House in the disused King William Street tube station, Grace Prior’s fears for her daughter’s safety became unendurable. Her mother engineered a position for Joan with the local branch of the Britannic Assurance at their office in Romford, closer to home. For a while, things settled down. But by late 1941 her mother’s protectionist instincts were increasingly at odds with Joan’s spirit of independence which was fuelled by the new Act of Conscription. If Joan must serve, she should apply to the senior service.

Fig. 1.4. Britannic Assurance Co. Ltd, Joan H. Prior, letter of appointment, 11 November 1940. Private papers of Joan Halverson Smith.

Grace Prior’s calculations were stratified according to her own finely calibrated prejudices. Her Victorian snobbery had been cultivated over a lifetime of graft and circumspection. And her bigotry, like all bigotry, was rooted in insecurity: fear of others. The daughter of a bootmaker who gambled his family to ruin, as a girl she sold newspapers for her mother outside Upton Park station. She clung to an unfounded belief that their family was descended from nobility and had claim to a pedigree from which, by some mysterious quirk of fate, they had been cruelly disinherited.

It was a grand myth, but it fed a genuine sense of superiority. So, when it came to her youngest daughter’s duty to her country, working in a factory or on the land was out of the question—the ATS were no better than they should be, and WAAFs romantically susceptible. By swift process of elimination, only the senior service, the Royal Navy, might offer the chance to rub shoulders with a better class of person.

Grace Prior, in arriving at this answer, had much in common with Jean Gordon’s wartime mothers sketched above. Yet shared assumptions afforded little comfort to