Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

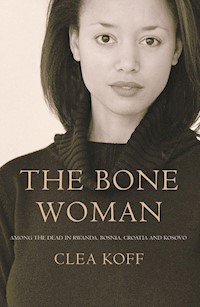

In the Spring of 1994, Rwanda was the scene of the first acts since the Second World War to be legally defined as genocide. Two years later, Clea Koff, a twenty-three-year-old forensic anthropologist, was one of sixteen scientists chosen by the United Nations International Criminal Tribunal to go to Rwanda to unearth physical evidence of war crimes and crimes against humanity. The Bone Woman is Koff's riveting, intimate account of that mission and six subsequent missions she undertook to Bosnia, Croatia and Kosovo on behalf of the UN. It is, ultimately, a story filled with hope, humanity and justice.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 464

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

THE BONE WOMAN

Clea Koff was born in England in 1972, and is the daughter of a Tanzanian mother and an American father. Her childhood was spent in England, Kenya, Tanzania, Somalia and the United States. When she was only 23 years old, she was invited to be a forensic expert for the UN International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda, and was the youngest member of the very first team to arrive in Kibuye in 1996. Clea Koff participated in seven UN missions in Rwanda and Former Yugoslavia. She was Deputy Chief Anthropologist in the Tribunal morgue in Kosovo in 2000. Clea Koff is now based in Los Angeles and Melbourne, Australia.

From the international reviews:

‘Forensic anthropologist Clea Koff worked on exhuming bodies from graves in Rwanda and the Balkans; The Bone Woman – her close-up look at genocide – is challenging but unforgettable.’ Andrea Levy, Guardian Books of the Year

‘The most impressive book about politics that I read this year [was] Clea Koff’s The Bone Woman. Moving from one mass grave to the next, she uncovers what really happened.’ Clive James, TLS Books of the Year

‘It is impossible to reach the end of this book without great admiration for Clea Koff’s tenacity and stoicism. . . Fascinating.’ Caroline Moorehead, Independent

‘Powerful.’ Giles Whittell, The Times

‘A compelling debut that is remarkable for exploring such a harrowing subject in a detached yet compassionate manner, striking a balance between scientific observation and human empathy. . . The Bone Woman humanizes the unimaginable. It clothes skeletons with feelings, gives unidentified bodies a voice and pieces together the severed lives of the survivors trying to come to terms with the grief and pain. . . Koff has the quality of a crusader, driven by a deeply held desire to expose human-rights abuses and a sense that a common humanity is shared by all.’ Claire Scobie, Scotland on Sunday

‘What fascinates here is a twin thread, the story of Koff’s own transformation, her “before” and “after” in the face of so much death. . . More often than not it is the tiny details about the remnants of violence that linger in your mind, but to read these is to be swept along by Koff’s passion, to admire someone whose work is gruesome yet necessary.’ Claire Fogg, Time Out

‘Clea Koff speaks eloquently for the dead in The Bone Woman, her poignant personal testimony about man’s inhumanity to man.’ Paul Majendie, Reuters

‘The beauty and significance of Koff’s work. . . comes through most powerfully when she is crouching over a mass grave, untangling limbs, scraping through dirt from a corpse’s clothes and finding, within, what most of us would see as horror, something human that speaks. . . Surprising, compelling and worth reading.’ Laura Secor, Washington Post

‘A brave book, presented in a clear voice by a scientist who is confident that her missions will get to the truth and yet human enough to cry at the horror of it all.’ Library Journal

‘Part science, part exposé, part personal narrative, The Bone Woman offers a rare insight into the role of a forensic anthropologist. . . But it also gives new meaning to conflicts and battles at places whose names were burned into international consciousness in the Nineties.’ Perth Sunday Times

‘Honest and effective . . . The writing is so personal that the reader may feel voyeuristic as Koff writes of her haunting dreams, the feelings of futility as killings continue around her, and the need to assimilate the objective nature of science with the subjectivity of human emotion . . . Few could convey the social and scientific complexities of forensic anthropology as sensitively and effectively as Clea Koff . . . A must read.’ Dawnie Wolfe Steadman, Globe and Mail (Canada)

‘A compelling, gruelling and profound book, filled with the trauma of our times. When you close it, though, your overall feeling is one of goodness (even nobility) seeping through the horror. . . Stunning.’ Jenny Crwys-Williams, Talk Radio 702 Book of the Year (South Africa)

‘The deep humanity. . . can be felt in every sentence, and gives Clea Koff’s work unimagined dignity.’ Die Welt (Germany)

First published in Australia and New Zealand in 2004 by Hodder Headline Australia Pty Limited (A member of the Hodder Headline Group)

First published in Great Britain as a jacketed trade paperback in 2004 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Grove Atlantic Ltd

Copyright © Clea Koff 2004

The moral right of Clea Koff to be identified as the authors of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright-holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 1 84354 139 4

Maps by Raylee Sloane

Text design and typesetting by Bookhouse, Sydney

Printed in Great Britain by Bookmarque, Croydon

Atlantic BooksAn imprint of Grove Atlantic LtdOrmond House26–27 Boswell StreetLondon WC1N 3JZ

Contents

Before

PART I

Rwanda: Kibuye 6 January–27 February 1996

The Blood’s Long Gone

‘They Killed Him as if They Didn’t Know Him’

The Grave

The Man with the Prosthetic Leg

‘Thank You Very Much for Your Work’

After-life

PART II

Rwanda: Kigali 3 June–24 June 1996

‘Everyone Knows a Genocide Happened Here’

The Hospital for the Dead People

Rwanda, Live

PART III

Bosnia 4 July–29 August 1996

Almost Picnic

I’m Just a Worker Here

The Morgue

Double Vision

PART IV

Croatia 30 August–30 September 1996

Seekers of the Living

The Translator

Voices of the Dead

The Mothers

PART V

Kosovo 2 April–3 June 2000 and 3 July–23 July 2000

‘What’s Ick-tee?’

The Grandfather

The Boy with the Marbles

The Swede at the Morgue

Spiritual Sustenance

The Old Man’s Third Bullet

After

Appendix: Tribunal Results

Acknowledgments

For the seekers of the silvery threads

Before

AT 10.30 IN THE MORNING ON TUESDAY 9 JANUARY 1996, I WAS ON A hillside in Rwanda, suddenly doing what I had always wanted to do. I took stock of my surroundings as though taking a photograph. I looked up: banana leaves. Down: a human skull. To my left: more banana leaves. To my right: a forest of small trees. Directly in front of me: air. I was sitting on a steep slope, in the midst of a banana grove. My knees were pulled up tight to stop me from slipping down—the skull hadn’t been so fortunate. It had rolled down to this point from higher up the slope, leaving behind the rest of its body.

This particular indignity had not been inflicted on this skull alone; indeed, I was surrounded by skulls, surrounded by people who had been killed on this very slope one and a half years earlier. Most of their heads had rolled away since then. I was there to find the heads and get them back to their bodies. After that reunion, there would be a chance at determining age, sex, stature, cause of death and maybe even who these people were. I crouched quietly, ‘listening’ to the skull. It was face-down and, so far, I had only been able to focus on the wound to the occipital: a strong blow to the back of the head with something sharp and big. I looked at the wound, the way the bone bent inwards, and the V-shape of the cut in cross-section. A mosquito buzzed by my ear and landed on the rim of the cut on the skull. ‘You won’t get much joy there, mate: the blood’s long gone from him,’ I thought, and brushed it away.

The way the skull was resting, I could see the maxillary (upper) teeth. One of the third molars had been erupting when this person was killed. I had just had my own wisdom teeth extracted before leaving for Rwanda and I ran my tongue thoughtfully over the fleshy sockets in my gums. It’s interesting how you can immediately look for points of comparison between your own body and the body in front of you. Is it empathy with their plight or relief that you’re still alive? I didn’t have time to contemplate this point further, as my body recovery partner, Roxana, came crashing through the leaves to my right, bringing with her Ralph, the photographer who would record the exact location and position of the skull. We rested a photo-board next to the skull, providing an identification number as well as the date, and an arrow pointing north. In the silence, we listened to the Nikon shutter open and close, twice.

This done, we could move the skull. I picked it up and turned it to see the face. And there it was in front of me: a tight, deep diagonal cut across the eyes and bridge of the nose. The cut had broken all the delicate bones that form that identifiable feature on all of us. It was painful to look at, so I put the skull down, exchanging it for a clipboard onto which Roxana and I recorded the condition of the bone, the number of teeth recovered, and the location of the skull on the hillside. When we had gathered all the information, we stabilised the skull where we had found it and ascended the slope, ducking under low-lying banana fronds and side-stepping sun-bleached vertebrae, into a grassy area replete with fragments of clothing. We were looking for our skull’s body. After clearing away the grass with our trowels, we found that some of the clothing held bones, partially buried in soil that had eroded from higher up the slope. Was this our man? The search was on.

This search and dozens like it continued for two weeks with varying success. There were four anthropologists scattered about the hillside, all of us engaged in the same task. Meanwhile, two archaeologists were on the crest of the hill, delineating the edges of the feature we would spend two months investigating: the mass grave behind the Kibuye church.

~ ~

I was twenty-three years old and part of a team of sixteen archaeologists, anthropologists, pathologists and autopsy assistants sent to Kibuye by the United Nations International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) after the 1994 genocide. ICTR is the sister tribunal to ICTY, the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia, which is prosecuting those responsible for war crimes and ‘ethnic cleansing’ in Bosnia–Herzegovina, Croatia and, now, Kosovo. ICTR and ICTY have the distinction of being the first international criminal tribunals since the Nuremberg trials following World War II. In 1995, ICTR’s Chief Prosecutor, Richard Goldstone, made an unprecedented request. He asked Physicians for Human Rights (PHR), a Boston-based non-governmental organisation, to bring together a team of forensic experts who could investigate mass graves for which ICTR had already indicted alleged perpetrators.

Judge Goldstone had turned to the right place. PHR had a network of health professionals at its fingertips and had previously retained forensic pathologists to conduct autopsies in cases of statesponsored human rights abuses in Israel. For the Tribunal job, they also had the services of Dr William Haglund, the UN’s Senior Scientific Expert, who would personally select the team.

When I got the call from Bill, I was a graduate student in forensic anthropology, but I had known for years that my goal was to help end human rights abuses by proving to would-be killers that bones can talk. Fortunately, I’d made no secret of this as I went through university; when Bill asked the forensic anthropologist Dr Alison Galloway to recommend students for the Rwanda mission, she apparently told him I was the only one she knew who was trained in forensic anthropology and interested in human rights investigations.

My inspiration was a man named Clyde Snow. I first read about him in Witnesses from the Grave: The Stories Bones Tell, which chronicles his creation of the Argentine Forensic Anthropology Team (EAAF). EAAF is now a world-renowned organisation of experts, but in 1984 they were a quiet group of graduate students brave enough to unearth and try to identify the remains of Argentines who were ‘disappeared’ during the military junta of the 1970s and ’80s. When I read Witnesses fromthe Grave, I was determined to help the team’s efforts, but first I had to gain the skills. Not only would I have to go to graduate school to train in forensic anthropology, I also had to finish the remaining three years of my anthropology degree at Stanford University.

I had gone to university already knowing that I wanted to work with human remains. This was actually a narrowing of a broad (and slightly odd) childhood interest in bones and things past. When I was seven, I was collecting the dead birds I found outside our Los Angeles house and burying them in a little graveyard. A few years later, in Kenya with my family, I collected bleached animal bones in Amboseli National Park while monkeys yelled in the trees above me. I put all the bones back the next day, after I had cleaned them gently. By the time I was thirteen, we were living in Washington, DC, and I was burying dead birds in plastic bags so I could dig them up later—I was curious how long it took them to ‘turn into’ skeletons. I took the stinking bags to my (somewhat horrified) science teacher for extracurricular and wholly self-motivated death investigations.

But when I was seventeen, in my last year of high school, I was firmly put on the track of human osteology. I chanced upon a National Geographic television documentary about how the ash from Italy’s Mount Vesuvius had preserved the remains of people killed in the volcano’s eruption nearly two thousand years ago. I was amazed when the anthropologist on the program said that she could tell from a set of bones that they were of a young female servant who had to carry heavy loads. I watched, enthralled, and took copious notes, including a ‘note to self’: study archaeology at Stanford.

But about halfway through the Stanford-in-Greece archaeological dig the following year, I realised I didn’t want to exhume ancient graveyards for research purposes. Those people had been buried ‘properly’. I wanted to investigate clandestine graves and the surface remains of crime victims, or of people whose deaths were accidental. My real interest was people who’d been recently killed and whose identities were unknown. Witnesses from the Grave taught me that forensic anthropologists deal with those bodies—and more than that, forensics could also be used to bring killers to justice.

Forensic anthropology is all about Before and After. Forensic anthropologists take what is left after a person has died and examine it to deduce what happened before death—both long before (antemortem) and just before or at the same time (perimortem). In addition to helping authorities determine the identity of deceased people, forensic anthropology has a role in human rights investigations, because a dead body can incriminate perpetrators who thought they’d silenced their victim forever. This is the part of forensic anthropology that drives me, this ‘kicking of bad guy ass’ when they least expect it.

I think I appreciate this use of forensics because I grew up well aware of the concepts and conditions of suppression and discrimination. My parents, David and Msindo, made documentary films about subjects like colonialism and resistance in Africa, the Israeli–Palestinian conflict, and the intersection of race and class in Britain. And they weren’t the type of parents to pack their kids off to bed while they had political discussions with their friends. My brother, Kimera, and I were always at the dinner table or the film screenings, learning terms like ‘lumpenproletariat’ before we had even heard of Sesame Street.

Our parents took us with them when they travelled for filming, and we were participants at our destinations, not tourists. Not being allowed much television also helped us grow up with little sense of national identity. Of course, our parents couldn’t have encouraged such a thing even if they’d wanted to: David has spent years abroad, although he’s a second-generation American of a Polish and Russian family, while Msindo was raised in England even though she’s Tanzanian with a half-Ugandan family. Instead of a national identity, we had a strong family identity.

The only time our parents didn’t keep us with them was when they went to Boston to protest against the censorship of their film Blacks Britannica. Suddenly, the focus of their work became tangible in our lives: they were away for half a year while Kimera and I stayed in Norfolk, England, on a friend’s pig farm. When I spent my sixth birthday separated from our parents, all I knew was that a serious injustice had been done to our parents’ film, and therefore to our parents, and therefore to our family. A few years later, I feared that some authority figure could again arbitrarily split up my family. We were at Nairobi airport when the passport control officer said he was going to detain my mother because he disagreed with the politics of the president of Tanzania, my mother’s country of birth. He directed the rest of my family to get on the plane without her. We almost missed the flight that day, and I nearly fainted from crying so hard. I was nine years old and I still remember the smirk on the officer’s face as he abused his power and enjoyed it.

So when I read about the Argentine Forensic Team in Witnesses from the Grave eight years later, I intuitively recognised their work as precisely the kind I wanted to do. For me, one photograph said it all: Clyde Snow standing up during the trial of officials responsible for the abduction and murders of thousands of people, showing a slide of the skull of one of those victims, Liliana Pererya. Through Clyde, this young woman was telling the court that she had been shot in the back of the head not long after giving birth to the baby she was carrying when she disappeared. Her remains were the physical evidence that would corroborate the living witnesses’ testimony. The state-sanctioned murderers doubtless thought they’d heard the last of her, but Clyde’s work was making them think again.

When I entered the Master’s program in forensic anthropology at the University of Arizona, I took the biggest step toward my dream. The U of A program applied human osteology to forensic cases through an arrangement with the Pima County Medical Examiner’s (ME’s) Office to handle all unidentified bodies. The first time I visited the U of A Human Identification Laboratory I saw walls of narrow cardboard boxes containing the skeletons of unclaimed people, an adjoining wet lab for removing flesh from bone under a fume hood, a darkroom for developing dental X-rays, and, in a distant corner, a coffee pot simmering quietly on a counter top. When I left the lab that day, I was so happy that I cried; the lab felt like a place where I belonged. There were only eight other students in the program, most of them had been there for several years already. I would be surrounded by mentors and, best of all, the director of the program, Dr Walt Birkby, was one of America’s greatest forensic anthropologists. But that wasn’t the only reason I wanted to fit in: the lab was his ‘shop’, and he was an ex-Marine with an iron-grey buzz cut and a staccato delivery. I didn’t want to find out what he would do if a student wasn’t up to his standards.

Fortunately, Walt took a liking to me, I think in part because of my enthusiasm and in part because of the training I already had in human osteology from Stanford, so I moved quickly from observing cases at the ME’s Office to processing them. The first time I saw a body—as distinguished from a skeleton—at the ME’s, I wasn’t shocked: I had seen bodies before, though it had been just the odd few, when my Stanford osteology classmates and I had visited the medical students dissecting corpses for their anatomy class next door. At that time, I didn’t think much of ‘fresh’, fleshed bodies, because it seemed all that tissue just got in the way of seeing the bones. But those donated cadavers couldn’t have been more different from the first body I saw at the ME’s. She had been lying in the desert for some time and was well on her way to full mummification. Her skin was so tanned and hard she reminded me of a big handbag—except high up on her inner thigh, where the skin had been protected from the sun. ‘Looks like JP FROG,’ Walt said and then added, for my benefit, ‘Just plain fuckin’ ran outta gas’.

Walt was climbing a ladder to take photographs before working on the body, so I turned to look at our second case, which was waiting on the next table. It was another woman, but she had died in her house and hadn’t been discovered for several days. As I glanced at her, I thought I saw her cheeks move. I thought, ‘Couldn’t be’, and went for a closer look: not only were her cheeks moving, but her tongue was actually turning in her partly open mouth because there were so many maggots in there, eating and jostling for position.

I don’t know what bothered me more, seeing that many live maggots or seeing a dead body move. Since everyone in the autopsy suite was wearing full protective gear, including a mask over nose and mouth, you couldn’t tell what people were thinking unless they spoke, but my eyes must have widened when I looked at the maggots because Todd Fenton, one of Walt’s long-time students, quietly said to me, ‘You’ll get used to them’. By this time, Walt was descending the ladder behind us and delegating tasks to start processing the first case.

Regardless of a corpse’s state of decomposition, the forensic anthropologist’s goal when processing a case is to analyse the specific bones which go through age- and sex-related changes, as well as the bony elements that indicate ancestry and enable an estimate of height. In general, we determine age by examining the face of the pubic symphysis (the very front of the two hip bones), the state of fusion of the epiphyses (end caps) of the long bones (arms and legs) and the medial clavicle (middle of the collar bone), and the morphology (shape) of the tips of the third and fourth ribs where they curve to meet the sternum. Of course, dentition is a great help with age as well, as teeth develop in rough accordance with chronological age. To determine the sex of an adult body without external genitalia (or with genitalia that are unrecognisable due to decomposition), several bones come into play: the entire set of bones that make up the pelvic girdle exhibit distinctions between males and females, as do the skull and several aspects of the long bones. ‘Race’, or ancestry, is an estimation that, again, relies upon the anthropologist’s interpretation of the morphology of bones throughout the body, with teeth and hair potentially contributing information. We estimate stature, or height, of a body by measuring the length of particular long bones and entering those measurements into formulae that take into account the sex and race of the body.

Now, when I say ‘regardless of a corpse’s state of decomposition’, I mean that even if the body is ‘fresh’—the person died that very day—you must use a Stryker saw (an instrument with a round blade that vibrates back and forth quickly, unable to cut tissue but able to saw through bone) to free up the section of bone you need to examine. You do not just cut or saw anywhere you feel like: there are ways to remove tissue with minimal disturbance of surrounding flesh or bone. For example, you must follow proper procedure for sawing out the maxillae and mandible (essentially, the mouth) in order to take dental X-rays, otherwise you risk cutting through the tips of tooth roots that sit in the maxillary sinus cavities.

I’m not going to pretend that a Stryker saw didn’t intimidate me the first time I had to use one. It’s quite heavy, can slide around in your hand if your surgical gloves are wet, and if it contacts liquid (say, blood in the intestinal region) it can spray that liquid everywhere. Plus, it’s difficult to believe a saw can’t cut you. But Angie Huxley, another of Walt’s senior students, said the magic words when I picked up the saw: ‘You can do it, Clea’. It helped, too, that the environment of the Pima County ME’s Office was efficient. Efficient is good when you’re doing something for the first time—it means that everyone’s concentrating on their own job and not watching you hold a Stryker saw with two hands like you’re corralling a cat for a bath.

The lab protocol dictated that once we removed the bony elements of interest, we signed them out from the ME’s Office (to maintain the chain of custody), and took them to the wet lab at the university where we cleaned them in several stages to remove tissue and fats. Then we anthropologically analysed them, took a full set of dental X-rays, and processed the films right there in the lab darkroom. Once the ME’s Office could send dental X-rays of missing persons whose characteristics matched our anthropological report, Walt could compare the sets to determine if the root formation, dental characteristics and restorations (fillings, bridges and so on) could be from our case. We would then submit to the ME’s Office a report of our findings.

My perspective on the evaluation of a skeleton for identification purposes is that, as anthropologists, we must take into account as much information as is available to us. Nothing is gained from using only one measurement, even if it is considered a reliable measurement. I think of us as interpreters of the skeleton’s language. Experience is the key to interpreting that language as accurately as possible, and experience comes from working on and observing as many cases as possible alongside a practised professional.

While I was gaining that experience at the Human ID Lab, I still thought that only international human rights investigations would have a humanitarian quality. A single case in Arizona dispelled that notion and, when I was invited to Rwanda, I remembered how fulfilling that case had been. We had brought an unidentified person’s dentition and other bones back to the lab from the ME’s. Several of us decided to finish processing the case that afternoon since we already had the dental X-rays of a missing person whose body the police suspected this might be. We established the age, sex, ancestry, stature and anomalies of the body. We shot the postmortem dental X-rays and processed them in the darkroom. Once the films were ready, Walt compared them with the missing person’s X-rays. It was a match. The decedent was a young man who had gone missing more than a year earlier.

Soon after Walt did the comparison, I packed my bag to leave, and went to say goodnight to Walt. As I reached the edge of the tall bookcase that separated Walt’s office from the main room, I realised he was on the phone to the medical investigator who was handling the young man’s case and would communicate with his family. Walt was leaning back in his chair, saying, ‘You can tell his folks he’ll be home for Thanksgiving’. There was pride in his voice— a voice that was usually either stern or joking—and my heart swelled because I knew I had been a part of this: our work meant the return of someone to his family, someone they might not have been able to identify on their own, someone they’d been missing. I have often read that surviving relatives feel that having a body, or even just a piece of one, is the key to closure and the gateway to grieving.

As I had imagined before graduate school, working with Walt in the ME’s Office was wonderful; but working on real cases had unexpected consequences. I began to draw inward, preferring to be home alone, where I read cosy British mysteries in an attempt to block out what I was seeing every week: the bodies of people who’d overdosed on drugs while with friends (friends so strungout that they hadn’t known what to do with the body except to dump it in the middle of nowhere), murdered ex-wives (shot and beaten, and in that order), foreign nationals who had died of exposure after paying a coyote to help them cross the US–Mexico border only to be abandoned in a relentless desert. Murders, suicides, car accidents, boating accidents, hiking falls, and on and on.

Eventually, I got spooked. I lived alone in a complex of hundreds of apartments spread across several acres at the edge of the desert. I was constantly checking my balcony doors to make sure they were locked. I even replaced the shower curtain with a transparent one so that if someone broke in, at least I’d see them coming. I had a neighbour I rarely saw—I think he was a salesman—and sometimes I convinced myself I could smell ‘decomp’ emanating from under his door.

Then, one evening, I was eating supper and watching the television news. The newscast played the 911-emergency tape of a woman telephoning for help as she was being attacked. I had just been down to the ME’s Office with Walt, examining that very woman. Walt had been asked to determine the sequence of the trauma. I remember the beginning of stubble on her shaved legs, her painted nails, the ragged bullet holes visible in her scalp when it was reflected down over her face, post-craniotomy. But when I heard the 911 tape, the memories weren’t ordered and discrete like I just recounted. It was more like hearing the voice of someone I knew, but someone I knew was dead. It scared the hell out of me.

In the midst of all this, the genocide in Rwanda took place, from April to June 1994. When I watched the TV reports describing the carnage as tribal conflict I knew enough to know better, but most of all I wondered to myself, ‘Who’s going to go over there and identify all those bodies?’ Less than two years later, I was on a plane to Rwanda.

~ ~

I joined the mission with great excitement because I was finally going to be applying my forensic skills to the human rights abuse investigations that had motivated me for years. Accordingly, I wasn’t particularly concerned that I would get spooked as I had in Arizona. I also didn’t expect to be demoralised by whatever we unearthed—after all, I was a trained scientist by then. I didn’t take stock of the fact that I was well prepared for the bodies but perhaps for nothing else.

Sure enough, when the mission was over and I returned home, it was as though my internal compass had been oriented to a different north. I see now that this was due in part to specific traumatic events during the mission and in part to identifying with Rwandans because I have family in three of the surrounding countries. In the end, however, my feelings of fulfilment intertwined with the unexpected and painful challenges of the work in such a way that I only wanted to do one thing: work on more missions.

At first I just needed to see if the work would be the same at another site, so I worked in Rwanda a second time in 1996. When I accepted a mission to Bosnia later that year with the UN International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia, I wanted to know how the work was different in another country. The next thing I knew, I was a core member of the UN forensic team, going on to investigate graves in Croatia and Kosovo. I did it often enough that being on a mission became more ‘my life’ than my life was, and I did it long enough to see the evolution of forensic investigation in the international setting, and for the setting to change around us.

As for the work itself—the graves and the bodies—that became familiar, too. In Rwanda, there might be hundreds of bodies in a single grave, predominantly women and children, killed by blunt or sharp force trauma. In Bosnia, there might be two hundred bodies per grave, predominantly men, their hands tied behind their backs, killed by high-velocity gunshot wounds (GSW). In Kosovo, we found several people in each grave, family groups, killed by a mix of GSW and burning.

By the time I worked in Kosovo, I was an ‘old hand’ at most of the protocols and quirks of Tribunal forensic missions; yet when I was in the morgue and saw the bodies—so many young, so many very old—I was reminded of Rwanda almost daily. The morgue itself couldn’t have been more different from the inflatable autopsy tent we had in Rwanda; this morgue was a built structure with running water, electricity and even fume hoods. But the bodies coming through that building could have been the same as those in Rwanda: a middle-aged woman carrying a child’s (her child’s?) pacifier, an old man wearing three layers of trousers, another woman carrying a stash of jewellery in an inner pocket. So many people shot in the back and buttocks, like those in Rwanda with the backs of their heads cut. In both places it was a story of people running away, or already incapacitated; a story of the people who didn’t, couldn’t, get away.

The bodies we recovered in Kosovo were those that hadn’t been removed by the police and Yugoslav National Army before our arrival. Some showed signs of the perpetrators’ attempts to hide the evidence (not so easy, really). That behaviour was the first legacy of forensic science’s entrance into the international consciousness. But it wasn’t the only legacy. I have come to understand that the role of forensic science in a global setting is not only to deter killing but also to contribute, in a post-conflict setting, to improved and real communication between ‘opposing’ parties. This is done by helping to establish the truth about the past—what happened and to whom—which in turn strengthens ties between people in their own communities. Despite the facts that are supposed to differentiate places like Rwanda and Kosovo—whether religious, ethnic, or historical—their dead have revealed their common humanity, one that we all share.

If someone had asked me about my career goal on my first mission to Rwanda, I would have said that I aspired to give a voice to people silenced by their own governments or militaries, people suppressed in the most final way: murdered and put in clandestine graves. Looked at from this perspective, working for the two United Nations International Criminal Tribunals as a forensic expert really was a dream come true for me. I felt that most keenly my first day on the job in Rwanda: I was crouched on a 45-degree slope, under a heavy canopy of banana leaves and ripe avocados, placing red flags in the dark soil wherever I found human remains. Let’s put it this way: I ran out of flags. I went back to my room that night and wrote in my journal about the realisation of a dream. And I kept on writing.

PART I

Rwanda: Kibuye

6 January–27 February 1996

RWANDA: KIBUYE

On 6 April 1994, the President of Rwanda, Juvenal Habyarimana, was killed in the sky over Kigali when a missile shot down the plane in which he was travelling. The identity of those who launched the missile is still argued over, although most evidence points to extremists within the president’s own political party. Within an hour of the downing of the plane, the Presidential Guard began killing people whose names were on lists created months earlier— anyone from political opponents to university professors and their students, ‘regular’ people, their families and anyone who had ever associated with them. Within a hundred days, more than 800 000 people—about a tenth of the population of Rwanda—were murdered, not by automatic weapons but by machetes and clubs wielded by soldiers, mayors, police, and neighbours, all urged to ‘do their work’ by 24-hour hate radio incitements. The organisers’ intent to expunge particular groups—even if those ‘groups’ were based on myths—is what defined these activities as genocide. It is also estimated that in this time, 70 000 women were raped and 350 000 children witnessed the murders of family members. The first massacre site marked for forensic investigation by the United Nations International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) was in Kibuye, on the western border of the country.

ONE

The Blood’s Long Gone

IT TOOK TWENTY-FOUR HOURS TO FLY FROM CALIFORNIA TO RWANDA. I crossed ten time zones and ate two breakfasts, but there was one constant: my thoughts of Kibuye church and the job I had to do there. Most of the facts I knew were bounded by the dates of the genocide: the church was in Kibuye town, within the préfecture, or county, of Kibuye. During the three months of the 1994 genocide, this one county alone suffered the deaths or disappearances of almost 250 000 people. Several thousand of those were killed at Kibuye church in a single incident.

According to the few Kibuye survivors, the préfet, or governor, of Kibuye organised gendarmes to direct people he had already targeted to be killed into two areas: the church and the stadium. The préfet told them it was for their own safety, that they would be protected from the violence spreading through the country. But after two weeks of being directed to these ‘safe zones’, those inside were attacked by the very police and militia who were supposed to be their protectors. This was a tactic typical of génocidaires all over Rwanda: to round up large numbers of victims in well-contained buildings and grounds with few avenues of escape and then to kill them. In fact, more people were killed in churches than in any other location in Rwanda. Some priests tried to protect those who had sought refuge in their churches; others remained silent or even aided the killers.

I read the witness accounts of the attack on Kibuye church in Death, Despair and Defiance, a publication of the organisation African Rights. Reading them was like having the survivors whisper directly in my ear: they describe how the massacre took place primarily on 17 April, a Sunday, on the peninsula where the church sits high above the shores of Lake Kivu. The attackers first threw a grenade amongst the hundreds of people gathered inside the church; then they fired shots to frighten or wound people. The small crater from the grenade explosion was still visible in the concrete floor almost two years later, along with the splintered pews. After the explosion, the attackers entered the church through the double wooden doors at the front. Using machetes, they began attacking anyone within arm’s reach. What had been a common farming implement became, in that moment, an instrument of mass killing, with a kind of simultaneity that bespeaks preplanning.

The massacre at Kibuye church and in the surrounding buildings and land, where more than four thousand people had taken refuge, continued for several days, the killers stopping only for meals. The hairs on the back of my neck stood up when I learned that the killers fired tear gas to force those still alive to cough or sit up. They then went straight to those people and killed them. They left the bodies where they fell.

People living in Kibuye after the genocide eventually buried the bodies from the church in mass graves on the peninsula. The UN International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda had requested our forensic team to locate the graves, and to exhume and analyse the remains to determine the number of bodies, their age, their sex, the nature of the trauma and the causes of their deaths. The physical evidence would be used at the trial of those already indicted by the Tribunal on charges of crimes against humanity, to provide proof of the events and to support the testimony of witnesses.

Every time I read the accounts of Kibuye survivors, I ended up crying because they describe a type of persecution from which there appears no escape, followed by a shock survival stripped of joy due to the murders of parents, children, cousins—and family so extended the English language doesn’t even have names for them, though Rwandans do. Reading those accounts one last time before the plane delivered me to Kigali, my reaction was no different, but I tried to hide the tears from people in the seats around me and that gave the crying a sort of desperation, which in turn caused me to wonder how I would handle working in an actual crime scene.

As I stepped out of the plane and walked across the tarmac to Kigali airport, my concerns faded because my immediate surroundings occupied me. The first thing I noticed in the terminal was that many of the lights were out and the high windows were broken, marred by bullet holes or lacking panes altogether: cool night air poured in from outside. Just inside the doors, the officer at passport control inspected my passport and visa closely.

‘How can you be a student and also come here to work?’ he asked. I told him I was with a team of anthropologists.

‘Who?’

Would he have a negative reaction to Tribunal-related activities?

‘Physicians for Human Rights,’ I replied nervously.

His face lit up. ‘Ah! Well, you are very welcome.’

Relieved to be past passport control, I walked downstairs to baggage claim. The baggage carousel was tiny, squeakily making its rounds, and I could see through the flaps in the wall to the outside where some young men were throwing the bags onto the carousel. My bags came through but two teammates I had just met on the plane, Dean Bamber and David Del Pino, were not so fortunate. The baggage handlers eventually crawled inside through the flaps in the wall and stood in a group, looking at the passengers whose bags hadn’t arrived as if to say to them, ‘Sorry, we did all we could’.

While Dean and David went to find help, I walked past the chain-link fence separating baggage claim from the lobby, pushed past the crowd of people there to meet this twice-weekly flight, and met Bill Haglund, our team leader. I recognised Bill because I had met him a couple of years earlier when he came to the annual meeting of forensic anthropologists in Nevada. He was a semicelebrity at the time, from his work as a medical examiner on the Green River serial murder cases in Seattle, but the reason he made an impression on me was his slide show from Croatia: he had just returned from working for Physicians for Human Rights (PHR), exhuming the remains of Croatian Serb civilians killed by the Croatian army in 1991. Now here he was in Kigali airport, just as I remembered him: wearing glasses, tie and hat, and his multicoloured beard (white, grey, blondish) seemed a bit straggly. In a hurried but low tone that I came to know well, Bill immediately started to brief me on the team’s logistics and plan of action, both for our two days in Kigali and the first stages of the mission in Kibuye. It sounded like an enormous amount of work—or was it just Bill’s rushed-hushed delivery?—but I was excited and felt ready for anything, particularly because Bill emphasised that no forensic team had ever attempted to exhume a grave of the size we expected. We would be pioneers together, learning and adapting as we worked.

By now, Dean and David had arranged for Bill to get their bags when the next flight came into Kigali in a few days, so we walked outside. Our project coordinator, Andrew Thomson, was waiting for us in a four-wheel drive.

As we drove into Kigali town, I could not believe I was there. You know it is Africa: the air is fresh and then sweet—strongly sweet, like honeysuckle. Kigali’s hills were dotted with lights from houses. On the road, the traffic was rather chaotic. Drivers did not use turn signals, they just turned or jockeyed for position as desired. Our boxy white Land Rover was one of many identical vehicles, though the others had the black UN insignia marked on their doors.

We checked in to the Kiyovu Hotel, but left almost immediately to have dinner in a neighbourhood of ex-embassies. The manicured tropicality of this area exuded another kind of African beauty, a kind of post-colonial Beverly Hills. Before dinner at a Chinese restaurant we met two more people who worked for the Tribunal; their high front gate was opened by a guard named God. The doors of the house lay open as though surveying the garden arrayed down the hill below. Standing there at that moment, I was at ease with my companions and tremendously happy to be in Rwanda. I was finally back in East Africa, a place I remembered from my childhood as exuding an abundant vibrancy of almost epic proportions.

Upon waking the next morning, I saw that at least the outskirts of Kigali did not dispel my memories. The suburbs consisted of a multitude of green hills lined with unpaved roads, and valleys filled with low red-roofed buildings. Flowers bloomed everywhere, and the contrast of green grass against orange earth was as saturated and luminous as a scene from Lawrence Durrell’s Alexandria. Even the grounds of the modest Kiyovu Hotel inspired awe: climbing vines with massive purple flowers coexisting with huge hawk-like birds nesting in the trees. The birds swooped out over the valley and came into view as I looked through my binoculars at the city, wondering how it would compare to all this.

We spent the next day and a half in town, gathering our exhumation equipment from the Tribunal’s offices to take to Kibuye by car. The roads in central Kigali were in excellent condition and allowed Bill to drive fast, roundabouts providing an extra thrill. When I wasn’t sliding across the backseat, I could see that Kigali’s hills seemed to create neighbourhoods through topography. People walked along the road, some carrying pots on their heads, while others tended the oleander bushes in the median dividers.

The Tribunal’s headquarters were in a small multi-level building which barely provided respite from the atmosphere of growing warmth and humidity. We set about unpacking the many boxes of equipment that had been shipped to Kigali in the previous weeks. As we sorted and inventoried the contents, it became clear that much of the equipment was either inadequate or simply absent: we had office supplies and rubber boots of various sizes, but the surgical gloves were three sizes too large; the scalpel handles were massive and their accompanying blades were so big I wondered if they were for veterinary pathologists; the ‘screens’ were all wrong and didn’t resemble the mesh trays needed to sift small bones and artefacts out of bucket loads of soil. There was no time to remedy the situation. We would simply have to be creative once we were in Kibuye.

We ate a late lunch at the Meridian Hotel, Bill challenging Dean, David and me to think about our purpose in the work for PHR and the Tribunal. He reminded us that our priority as forensic anthropologists in Kibuye would be to determine age and sex, gather evidence of cause of death, and examine for defence wounds. The conversation was as yet removed from reality because we hadn’t begun the exhumation. It was more about expectation and almost academic distance—Bill even asked us what sort of bone remodelling we might expect in people who had regularly carried heavy weights on their heads.

When the conversation turned back to human rights and the right to a decent life, David told us about retrieving human remains from a mine in Chile, where he had helped found the Chilean Forensic Anthropology Team. He talked of how it took hours to just climb up and down the 200-metre-deep pit on a rope, retrieving the skeletons bone by bone, and of having to deal with the grief of the families sitting on the edge of the mine shaft. Although it was the highlight of the day to talk together like this, as we sat in the shadow of the hotel I began to feel chilly.

I couldn’t shake the feeling even during dinner at an outdoor Ethiopian restaurant set amongst other houses on an unpaved back road. At one point, four men dressed in different styles of Rwandan military uniforms strolled into the restaurant. They were carrying machine guns. I don’t know what I expected to happen—were they there to eat or to arrest someone?—but everyone just looked at them and they looked back and then strolled out. Whether out of tension or jet lag, I suddenly lost my appetite; Dean and David weren’t eating much either. We watched Bill tuck into his dinner but on the way back to our hotel, David said to me, ‘You didn’t eat much. You are still hungry.’ It wasn’t a question.

After a fitful night of being awoken by small lizards taking refuge in my room and the sound of the linoleum peeling up from the floor (conjuring up visions of a caterpillar the size of a small dog chewing through dry leaves) I joined Dean and David to go to the UN Headquarters to get our UN driver’s licences and identity cards. This was my introduction to the true international character of the UN and a glimpse of the bureaucracy for which it is infamous. The HQ, the old Amohoro Hotel, was buzzing with activity: cars passing in and out of the guarded gate, armed soldiers from all over the world escorting us, people charging around apparently getting things done, everyone wearing the blue beret of the UN at a rakish angle.

While our IDs were being processed, Dean, David and I walked around the corner of the building to the Transport Office for our driver’s licences. The test consisted of driving up the street, round the roundabout and back again. We all passed. The examiner went over the rules of driving a UN vehicle, but he spent most of the time berating us about the frequency with which these are disregarded, as though we had already transgressed.

Drolleries aside, those two bits of identification were essential: our identity cards and licences gave us immunity, free passage and protection from personal or vehicle search. We were to wear them on a little chain around our necks at all times. With our newly laminated cards sticking to our sweaty chests, we walked back to the Tribunal building and loaded up the Land Rover and trailer for the drive to Kibuye. Bill was staying in Kigali that night, so he had arranged for two ICTR investigators, Dan and Phil, to escort us to Kibuye. Although Kibuye was only about ninety kilometres to the west, it would be a four-hour drive, slowed by periodic Rwandan Patriotic Army (RPA) roadblocks and sections of unfinished road.

~ ~

My first impressions of Rwanda beyond Kigali came through a soundtrack of ABBA pouring loudly out of the car stereo via Dan’s Walkman. The initial forty minutes of the drive were on paved road; the latter three hours began on an unfinished graded surface and ended on potholed dirt, so those of us in the backseat could only see out of the windows when we weren’t airborne. But as we drove, I felt so light, anticipatory and excited at what was to come that I believe I hardly blinked and I couldn’t stop smiling to myself.

The scenery was encouraging these feelings: being in East Africa made me think gratefully of my parents, and I was happy to see Africans again; their proud carriage made me want to sit up straight. Out the window, all was majestic beauty: I could see the transition of the land from the flatter parts near Kigali to the uplifted, mountainous region toward the west where we were headed; the hills were cultivated with tea, bananas and coffee plants in vista after vista of patchwork slopes sprinkled with thatch-roofed huts and mud-brick houses. The people walking along the side of the roads between the villages carried pots and harvest food on their heads and babies on their backs. Children waved at us as we passed.

Each town had a roadblock where we had to stop the car. A young soldier would then emerge from a small building and indicate that we should reverse three feet or pull over, or whatever he felt like making us do, before coming to the window to inspect every person’s identity card and ask in French where we were going, where we had come from and what we were doing. Then, once he had established that he was in control by having us keep the car idle for several minutes, he would indicate to another soldier to drop the rope barrier so we could drive on.

When we finally got a glimpse of Lake Kivu, it was breathtaking because the road dropped out of the mountain to flatten down along the water’s edge like a rollercoaster ride, before climbing again into Kibuye town. When we drove past Kibuye church, it was very different from what I had envisioned, but when I saw more of the country, I recognised the architecture as typical of a Rwandan Roman Catholic church built in the 1960s by Belgian priests: tall and cavernous with a stone finish, stained glass windows and a bell tower. However, reading the Kibuye witness statements hadn’t prepared me for how isolated it seemed: from the road, the church appeared to be the only building on the crest of a peninsula, accessible only by water or the one road.

Further down that road, we left the equipment trailer with our UN military guard unit, already based at the Eden Roc Hotel, before we continued on to the Kibuye Guest House. This had a main building containing the reception, restaurant, kitchen and lake-side verandah, with gravel pathways leading to nine or ten circular, thatch-roofed huts spread about well-kept grounds of lawn and nasturtiums. The setting was idyllic, which was fitting as the guest house had been a water-skiing resort before the genocide. I’d never stayed in anything close to a resort so I was bowled over by its luxury—the palm and pine trees amidst lush grass (cut by hand with something like a panga, a few blades at a time), bordering a small beach, and the sound of lapping water from the vast lake stretching to a horizon created by Zaire’s mountains in the great distance directly to the west.