Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: CompanionHouse Books

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

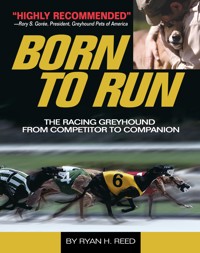

In chronicling his travels to many of America's dog tracks, Greyhound owner and adoption advocate Ryan H. Reed shatters misconceptions about the controversial sport of Greyhound racing. Reed uncovers a world of magnificent canine athletes and their devoted owners and trainers. With amazing color photographs of the dogs in action, Born to Run gives readers a behind-the-scenes look at the daily activities of breeding kennels, racetracks, and adoption centers, detailing the lives of racing Greyhounds from puppyhood to their competitive careers to their lives as cherished pets after retirement.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 177

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Andrew DePrisco, June Kikuchi

EDITORIAL DIRECTORS

Amy Deputato

SENIOR EDITOR

Jarelle S. Stein

EDITOR

Jennifer Calvert

ASSOCIATE EDITOR

Elizabeth Spurbeck

ASSISTANT EDITOR

Véronique Bos

SENIOR ART DIRECTOR

Karen Julian

PUBLISHING COORDINATOR

Tracy Burns

PRODUCTION COORDINATOR

Jessica Jaensch

PRODUCTION COORDINATOR

Photographs © 2010 by Ryan H. Reed

Copyright © 2010 by I-5 Press™

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of I-5 Press™, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in an acknowledged review.

I-5 Press™

A Division of I-5 Publishing, LLC™

3 Burroughs, Irvine, CA 92618 USA

www.facebook.com/i5press

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Reed, Ryan H., 1968-

Born to run : the racing greyhound from competitor to companion / by

Ryan H. Reed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-59378-689-2

eISBN: 978-1-62008-052-8

1. Racing greyhound. 2. Greyhound racing. I. Title.

SF429.G8R425 2010

798.8'5--dc22

2009050555

Printed and bound in China

16 15 14 13 12 11 10 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

Contents

Acknowledgments

Preface

Introduction

Chapter 1: Northeastern Style

Chapter 2: Vision of Sunshine

Chapter 3: Corn Belt Revival

Chapter 4: Kansan Kaleidoscope

Chapter 5: Sweet Home Abilene

Chapter 6: Lone Star Rising

Chapter 7: Rocky Mountain Mosaic

Chapter 8: Northwest Tradition

Chapter 9: Extraordinary Pets

Dino & Abby’s Road Trip

Glossary

Greyhound Track Abbreviations

Bibliography

Special Thanks

Dedication

For my sweet Toolie.

My lucky star fell the day you came to me. We did everything together, and how I adored you. Now, all these years later, if I could tell you just one thing, it would be that my chest became a vacuum the day you left.

May 23, 1986 – January 5, 2000

Acknowledgments

Like most large-scale research projects, this book could not have been realized without the continued support of many friends and backers. Janice Mosher, an adoption volunteer with Greyhound Pets, Incorporated, and a close personal friend, helped in countless ways throughout the entire effort. Gary Guccione, executive director for the National Greyhound Association, made arrangements for me to visit breeding farms near Abilene, Kansas; explained the history of the sport; and assisted in a great many other ways, too numerous to list here. At the Greyhound Hall of Fame, Ed Scheele and Kathy Lounsbury helped supply historical information.

The lion’s share of statistical background information for individual Greyhounds was provided by Greyhound-Data.com, a free Web site with information—including race history—compiled by teams of aficionados from Australia, New Zealand, Europe, and the United States. Without the Greyhound-Data Web site and the hard work put into its database by tireless volunteers, it would not have been possible to provide such detailed information about the racing and retired Greyhounds portrayed in this book.

In August 2002, I had the great fortune to be befriended by Vera Filipelli, the director of media relations at Derby Lane racetrack in St. Petersburg, Florida. She and her husband, John, made a trip to Derby Lane feasible for me by insisting that I stay at their home for a week to offset some of the costs. Afterward, Vera continued to help in more ways than I can enumerate here. Simply put, without Vera’s unwavering support and friendship, this book would have been much smaller in scope and size; in fact, it might not have been completed at all.

With Vera’s help, I got in touch with the Rhode Island Greyhound Owners Association (RIGOA), which generously awarded me a grant that allowed for a trip to Lincoln Park. While I was photographing matinee races at the racetrack, my camera body suffered a catastrophic failure, putting a halt to any further photography. In a near panic, I called RIGOA president Richard Brindle and vice president Dan Ryan, who immediately offered to pay for a new camera body. They are two of the most benevolent men I have ever met.

Later, in December 2005, I received yet another generous grant for my work, this one from the Texas Greyhound Association (TGA). While in the famed Lone Star State, I had the opportunity to document the TGA-owned schooling racetrack in Bruceville; a Greyhound breeding farm; and the Gulf, Corpus Christi, and Valley Greyhound Parks. The kindness and professionalism of TGA executive director Diane Whiteley and TGA executive assistant Lois Mowery exceeded my wildest expectations. Without the RIGOA and TGA grants, the Rhode Island and Texas chapters in this book would not exist.

Other types of valuable assistance were provided by Don Conatser, Judy Enyard, Maurice Flynn Jr., Jim Gartland, Cheryl Gilson, Rory Gorée, Herb “Dutch” Koerner, Patti Lehnert, Connie Loubsack, John Manning, Charles Marriott, Craig Randle, Steve Rose, Ann Waitley, and Carl Wilson. Countless others contributed in valuable ways to this book project. Without their collective support, Born to Run would never have become a reality.

Finally, I would like to express my deepest appreciation to my parents, John and Rosemary Zimmerman, who never lost faith in my ability to complete this project.

Preface

The seeds of this book were planted in the Pacific Northwest some twenty years prior to its publication. In 1989, at twenty years old, I realized that something was missing in my life—companionship. After visiting a friend who had just adopted a black Lab puppy, I realized that I needed a dog.

Having never adopted a dog before, I realized I needed to do some research. I turned to the local library, searching through its books to gain any tidbits of information I could. After browsing through the small selection of dog books available, I pulled out an encyclopedia and looked up the word dog. A full-color insert showed illustrations of every dog breed. In the most defining moment of my life, my eyes slowly wandered to the Greyhound illustration, which depicted a weird-looking, aerodynamic creature. That casual glance would profoundly change my life.

When my older brother heard about my new interest, he suggested that I call the Coeur d’Alene Greyhound Park in northern Idaho for information. His college roommate was a regular patron and had once mentioned something about adopting a retired racer from there. That was the first time I had ever heard about Greyhound racing. I called the racetrack the following morning and was referred to the Greyhound Pets of America’s Idaho chapter in nearby Post Falls. When I explained to the adoption volunteer what kind of dog I was looking for, she replied, “Oh, I’ve got a pup that would be just perfect for you. Her name is Toolie.” I later visited the racetrack, where Toolie had once greeted patrons, and saw how much the trainers enjoyed being around the dogs and how well they cared for them—the affection was genuine.

Illustrating a sharp contrast in design, Toolie’s (R’s Snowbird–SC, CD) streamlined profile counters the rigid lines of an old steam locomotive in a Potlatch, Idaho, city park.

A few months after adopting the white-ticked beauty, I joined the adoption group and set out to find as many homes for retired racers as I could. In my first six months, I placed a dozen retired racers and was subsequently voted onto the board of directors at the age of twenty-one. For years afterward, I served the adoption organization by handling media relations, conducting home visits and interviewing potential adopters, providing long-distance transportation, managing a weekly Greyhound get-together, and even repossessing a retired racer here and there for various reasons. While I maintained an interest in learning more about the sport of Greyhound racing, nearly all of my firsthand experience with Greyhounds came from the realm of adoption.

When I adopted my second-generation pups, Dino and Abby, in April 2001, I began to chat with other adopters on Internet discussion boards. I quickly discovered that people had incredibly strong opinions about racing, but when asked how many racetracks or breeding farms they had been to, the answer was almost always, “None.” I was struck by the fact that a person could have such strong feelings about something he had never seen for himself. I remembered dogs coming into our adoption kennel who were happy, healthy, bouncing, and acting like everyone in the world was their best friend. I knew that if the dogs were indeed universally mistreated, as some people claimed, they would require a great amount of behavioral modification before being released to adopters. But the dogs went happily into adopters’ homes, often immediately after retiring from racing. This is what made me think about doing a book about Greyhound racing and adoption—I needed to see for myself how these dogs lived before they arrived for adoption.

I started the book project in the summer of 2001 in an effort to travel to and gather information on racetracks, breeding farms, and adoption organizations across the country as well as to learn the history of Greyhound racing in America. The first racetrack I approached was the Multnomah Greyhound Park, located in Portland, Oregon. I came with no references and could not even say I knew anyone in racing, yet they gave me full access to the racetrack and allowed me to photograph anything I wanted to. My first thought was, "Incredible! Not only do these people have absolutely nothing to hide, they’re extremely proud of what they are doing."

I next traveled to the National Greyhound Association facility in Abilene, Kansas, and visited several other racetracks located in Colorado, Kansas, and Iowa. I had not previously met Gary Guccione of the NGA, yet he took half a day of his own time to arrange several farm visits for me. I told him I had been an adoption volunteer in the past, and that was good enough for him. Craig Randle, the NGA’s chief farm inspector, drove me from farm to farm, answering questions along the way.

From 2002 to late 2005, I continued to visit racetracks in Florida, Rhode Island, Texas, and again in the Midwest. I began to see the book project as a work on Greyhound racing and adoption in America, and I set out to expose every nook and cranny with my camera and my pen. What I saw along the way were healthy and happy-go-lucky Greyhounds. Every dog acted as though I were his long-lost friend. My own dogs acted as though every breeding farm they visited was their old home. I had never seen them so happy before—or so disappointed when the visits were over.

During the years I was conducting my research, I began to realize that there was a family environment within Greyhound racing that was separate yet overlapped with the family of those in Greyhound adoption. It also became apparent to me that Greyhound breeders were not in the business for mere profit. They were a collection of people who simply loved being with the dogs. A breeder in Oregon once told me, “If I were to put the same amount of effort into any other business than raising Greyhounds, I would be a millionaire!” I realized that there was no chasm between racing people and adoption people. They stood on the same ground with the same ideology.

The dogs themselves genuinely love the competition and athleticism of their sport—a love they feel even years after retirement. At the Abilene Greyhound Park, my retired dogs got to run on the racetrack one last time—down the frontstretch and into the first turn. After the mock race, a handler walked them over to me in the pens. They had looks on their faces that seemed to say, "Did you see us, Daddy? Huh? Huh? Did you see us?" That was a wonderful moment for me.

Conversely, one of the worst things I experienced while creating this book was standing next to a group of trainers when a dog took a spill on the first turn. There was a collective gasp, and I heard a trainer cry out the dog’s pet name in a way that wrenched my soul. The animal was entirely uninjured, even finishing the race, but the trainer was deeply shaken. None of the other trainers laughed or made fun of her because they had all been there before. Another difficult moment for me was watching a trainer worry about the fate of a sick dog. He was leaning on a fence, overwhelmed with concern for his pup. This was a very large individual—a man you might expect to meet in a raucous bar somewhere. But there he was, hunched over, with two other old trainers comforting him. I could have taken a picture—and I wanted to—but I couldn’t bring myself to intrude on the man’s painful moment.

These people care deeply about their dogs. On Fourth of July, they are in the kennel buildings to comfort thunder-phobic dogs that are frightened by the loud fireworks, often climbing into the crates with the dogs. On Christmas Eve and Christmas Day, as on any other day, they are in the kennel buildings, scrubbing food bowls and sweeping floors. While visiting the racetracks, I saw a universal dedication far beyond even that in the pet world at large. While I was learning firsthand, individuals on the Internet were still talking about how all of the dogs are terribly mistreated. But I learned the truth. As a dog lover who had taken his first steps with Greyhounds two decades prior, it was a truth I admired and wanted to share with others. I continued to support Greyhounds and racing because I discovered that the world of Greyhound racing is made up of dog lovers who have made great strides in promoting adoption and have developed productive relationships with adoption organizations. Everything I saw is represented in this book, from beginning to finish and from coast to coast. It is the world of Greyhound racing and adoption, and it is as unique as it is incredible.

Introduction

The Greyhound has the eyes of a philosopher and the soul of an ancient hunter. So old is the breed that the origins and true meaning of its name have been lost to history. The word grey was corrupted from something—perhaps “to gaze” or “that which is great.” Unfortunately, we may never know why the dogs were labeled grey hounds. What is certain is that the Greyhound has walked beside us from the beginning of recorded history and is a companion not just to individual humans but to humankind.

During the mid-nineteenth century, Americans imported Greyhounds to help control the spread of jackrabbits, which were destroying crops throughout the Midwest. Soon after the dogs’ arrival, coursing clubs began to form, and in 1886 the American Coursing Board was founded as the first national coursing registry in the country. In October 1906, the National Coursing Association—renamed National Greyhound Association in 1973—was established using the registration records from the by-then-defunct American Coursing Board.

The actual sport of Greyhound racing as it is known today was the brainchild of Owen Patrick Smith, an inventor who spent years developing a practical mechanical lure system. In 1919, O. P. Smith opened his first racetrack in Emeryville, California, with a mechanical lure that weighed some 1,500 pounds. Known as the Blue Star Amusement Company, the racetrack lay on the outer fringes of Oakland and rarely drew a crowd of more than three hundred spectators.

In our technological age of highspeed this and drive-through that, the one thing that can still touch the human spirit like nothing else is the special bond between people and their dogs. Simplistic in nature, it is ancient and powerful.

Running lighter than air, Iowa-bred L’s Main Event is just seconds away from earning his first win at Bluffs Run Casino. Roughly a year later, he matured into a grade-A racer at the Dubuque Greyhound Park in Dubuque, Iowa.

Without pari-mutuel wagering in place, the sole purpose of the racetrack was to exhibit the sights and sounds of Greyhounds in full flight, with profits generated entirely by gate receipts—a way of operating that would never be repeated by future racetracks. After the 1921 season meet, Smith’s first and short-lived racetrack was understandably relegated to history.

In 1921, Smith opened four racetracks in Florida, Illinois, Kansas, and Oklahoma. The Mid Continent Park in Tulsa, Oklahoma, was the first financially successful operation. Incredibly, to find enough Greyhounds to actually race at the Mid Continent Park, Smith was forced to drive from one local farm to another in an effort to round up as many Greyhounds as he could.

For the small number of Greyhound owners and their canine athletes, life was anything but stationary during the 1920s. Most traveled across the country either on passenger trains or in their Tin Lizzies with luggage strapped to their roofs and a couple of dogs riding in their back-seats. Owners, fascinated by the new sport, would drive thousands of miles over dusty or muddy country back roads to reach distant racetracks, some of which were only rumored to have opened. Such was the mindset during the 1920s, when most people were able to enjoy leisure, travel, and sport for the first time in American history.

With less than three dozen Greyhounds available to race at almost any given racetrack during the time, many races had only two dogs competing against each other—essentially a match race. Most Greyhounds raced at least twice a day, with the winners pitted against each other until one dog remained unbeaten. Sometimes as many as six dogs would take to the racetrack at once, being released from an early version of the starting box with doors that opened vertically.

Despite the initial scarcity of competitors, Greyhound racing began setting down firm roots in the country, which allowed it to survive not only the turbulence of the twenties but also the depredations of the Great Depression and the demands of World War II. In January of 1945, the director of War Mobilization and Reconversion closed both Greyhound and Thoroughbred racetracks throughout the country to save labor and critical materials for the war effort. The sport of Greyhound racing entered the 1950s as an established, albeit localized, spectator sport. In 1950, twenty-seven racetracks in seven states—as well as one in Tijuana, Mexico—hosted seasonal racing meets that lasted for several months each year.

During that same year, the Hartwell grading system was employed for the first time at the Cavalier Kennel Club, situated in Moyock, North Carolina. The grading system, named after its inventor, Paul Hartwell, assigns Greyhounds to a specific grade—A, B, C, D, and so on—that ensures a Greyhound with certain speed abilities will race against other Greyhounds of the same skill level and ensures fairness by giving each racer an equal number of starts. Although some racetracks have tweaked the procedures of the grading system, it remains in use today.

Throughout its storied history, the sport of Greyhound racing has evolved from a collection of dusty racetracks peppered over several states to a national industry that spends great resources on the care and welfare of its canine athletes. Welfare guidelines created by the National Greyhound Association cover nutrition, housing, kennel cleanliness, exercise, and health of Greyhounds. To enforce its welfare guidelines, the NGA sends unannounced inspectors to breeding farms annually.

From the onset of racing in 1919, owners began to employ the practice of selective breeding in an effort to create the fastest dog possible. As a result, the racing Greyhound slowly but surely morphed into something different from its canine forefathers and even from its contemporary American Kennel Club relatives bred for conformation.

The actual practice of selective breeding is an inexact science, as Greyhound breeders will freely admit. But as the old saying goes, “like tends to beget like.” With nearly a century of selective breeding to improve attributes such as good health, athletic fortitude, confidence, and intelligence, the racing Greyhound known today is an extremely healthy breed and also a wonderful pet that has found its way into thousands of homes throughout the country.

The racing industry has formed numerous positive relationships with adoption organizations; with their combined efforts, the goal of a national 100 percent adoption rate is being realized. Currently, out of around 26,000 Greyhounds registered each year, roughly 20,000 are adopted to private homes and another 4,250 are returned to breeding farms to either bring in the next generation or live out their lives as pets. Thanks to the efforts of adoption volunteers and support from the racing industry, the retired racing Greyhound is now accepted by the American public as one of the best house pets a family can own.

With a dark brindle coat—a color of wild dogs—Abby (Courtney Rush–PH, AP, TU) recreates the look of an ancient ancestor while lying in a shady Salem, Oregon, backyard. The brindle coat serves as camouflage and is a product of a gene passed on from Greyhound to Greyhound for thousands of years.