28,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

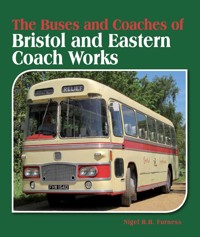

The Buses and Coaches of Bristol and Eastern Coach Works outlines the history of Bristol Commercial Vehicles and Eastern Coach Works (ECW), two manufacturers that together developed some of the most familiar buses and coaches of the twentieth century. The book covers the full production histories and specifications for the standard range of models produced from 1936 to 1983. The variety of engines used to power Bristol-ECW is outlined and a mechanical specification for each chassis is provided, along with a description of the different body styles produced by ECW for each chassis. There is also a chapter on owners' experiences and advice on buying a bus for preservation.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

The Buses and Coaches of Bristol and Eastern Coach Works

Nigel R.B. Furness

THE CROWOOD PRESS

First published in 2014 byThe Crowood Press LtdRamsbury, MarlboroughWiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2014

© Nigel Furness 2014

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 84797 698 7

CONTENTS

Introduction and Acknowledgements

CHAPTER 1 BRISTOL AND THE BIRTH OF THE MOTOR BUS

CHAPTER 2 DEVELOPMENT OF THE BRISTOL CHASSIS

CHAPTER 3 LOWESTOFT AND THE COACH WORKS

CHAPTER 4 THE THIRTIES, DAWN OF THE DIESEL ENGINE

CHAPTER 5 STANDARD BUSES FOR THE TILLING GROUP

CHAPTER 6 THE ENGINES

CHAPTER 7 THE POST-WAR STANDARDS

CHAPTER 8 FIFTIES INNOVATION, THE LODEKKA

CHAPTER 9 UNDERFLOOR ADVENTURE

CHAPTER 10 SMALL CAPACITY, LIGHTER WEIGHT

CHAPTER 11 THE SIXTIES, REAR ENGINE ERA

CHAPTER 12 A DOUBLE-DECKER FOR THE SEVENTIES AND BEYOND

CHAPTER 13 A NEW LIGHTWEIGHT

CHAPTER 14 PRESERVATION

References

Bibliography and Further Reading

Index

INTRODUCTION

I became acquainted with Bristol’s indigenous buses in my earliest years, as they were my mother’s only means of transporting her young family around Bristol at that time – the story of my father’s first car being worthy of a book of its own. My earliest bus memory is of clinging on to the Claytonrite-wrapped platform handrail of a post-war K on Durdham Downs whilst my mother folded my push-chair, frightened to let go yet ready to jump if by chance the bus left without her, and screaming blue murder when the driver let in the clutch with a bang. I must have been about three years old at the time, but even then I could recognize and mimic the sound of a Bristol bus gearbox as it was driven away from the kerb, though I was reluctant to do it in public!

By the time I was in my teens I had developed an interest in the mechanical workings of buses, trucks and heavy plant largely through observation of the myriad motorway construction and road improvement contracts that characterized the 1960s. Bristol’s buses also provided a pleasant distraction from the rigours of grammar school, and salvation from the depredations of the rugby pitch.

During my school days they were my own personal transport. You would be surprised how many regular travellers, male and female, young and old, were quite knowledgeable about the buses they used. The ‘Summer of Love’ and ‘Sergeant Pepper’ passed unnoticed whilst I haunted the Central Repair Works of the Bristol Omnibus Company in every spare moment, hoping to see rare vehicles such as the SUS and brand new ones like the RELL. You wouldn’t be allowed through the gates today, especially with a camera, but as long as you asked nicely and promised to behave, in those days you could generally roam freely. Bringing cake often helped to ease one’s passage into the works, which is where my education into the history of Bristol and ECW began.

Ignoring a short-lived unsuccessful venture with Thornycrofts and FIATS, the earliest Bristol buses were totally home-grown in both body and chassis. However, as the bus industry developed, Bristol chassis were more often bodied by ECW at Lowestoft than anywhere else. This state of affairs came about by the financial expertise of Sir J. Frederick Heaton, chairman of the Tilling Group, knighted for his war work and a highly respected accountant and businessman in the 1930s. Heaton made a pact with the railways that allowed his Tilling Group to acquire controlling interests in both United Automobile Services and the Bristol Tramways and Carriage Company Ltd. United Automobile built its own bus bodies at a coach works in Lowestoft, and Bristol Tramways built chassis and bodies at Brislington, a few miles from the centre of Bristol.

Following the 1930 Road Traffic Act, the Tilling Group needed modern rolling stock to replace the motley collection of vehicles inherited from the multiplicity of small operators forced out of business by the Act and absorbed into Heaton’s bus companies. For Heaton, the logic of building his own buses was not only irrefutable but in his blood, so to speak, for Tilling themselves had found the early off-the-peg motor buses poor things and so manufactured their own, powered by petrol-electric technology. Bristol Tramways built complete buses, but had insufficient capacity to supply the whole Tilling Group. The coach works at Lowestoft was developed, and ECW was established as a company to manufacture bus bodies for the Tilling Group. Thus began a long relationship between Brislington and Lowestoft.

In 1948, Bristol Tramways and ECW became state owned. This meant that both could only sell to companies in which the government had a shareholding, so they were forced to function even more closely as a unit. Between 1948 and 1965 all but a very few Lowestoft bodies were fitted to Bristol chassis, and vice versa. This is the period in which the Bristol/ECW product became most clearly defined as a recognizable unit. The engineers at Brislington and Lowestoft worked together with the operating companies to produce a visually and physically consistent family of vehicles.

Until the early 1960s, there was a tendency amongst operators to treat bodies and chassis as separate entities, which could be mixed and matched as required, mostly because early bodies did not always last as well as the chassis upon which they were mounted. Sometimes the only clue to the identity of an apparently new vehicle was the registration number, which generally remained with the chassis, unlike in London where London Transport turned this principle into an art form at their Aldenham Bus Overhaul Works. Someone once told me that Aldenham had a huge pile of RT bus parts and a huge pile of registration numbers, and just permuted any combination of these into a bus as they felt like it.

With the introduction of alloy-framed bodies by ECW and others in the 1950s, they become much more robust and long-lived, with only a change of use, accident damage or fire causing new bodies to be fitted on the chassis. Add to that the semi-integration of body and chassis that were features of several post-war Bristol/ECW products, and a well defined and consistent identity emerges.

As this is being written in late 2013, there are a few Bristol/ECW buses still to be found in service, though their time is limited as legislation and modern technology conspire to end their working lives. Such is the ruggedness of the product, and its popularity with enthusiasts, that many remain in private ownership, preserved and lovingly maintained, or being restored (often at enormous cost) for all of us to enjoy. All play their part in reminding us of the days when buses were built at Bristol and Lowestoft, and Britain was a manufacturing power in the world, so it seems timely to bring the story of Bristol and ECW to another generation of enthusiasts.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

In consideration of the subject matter, precedence has been given to the combinations of Bristol chassis with ECW bodywork. Space limitations preclude detailed consideration of the ‘foreign’ combinations of Bristol chassis with other bodies, likewise Eastern Coach Works (ECW) bodies with other chassis, though these have not and should not be ignored. The B45 Olympian, essentially a Leyland product, and other ventures pursued separately by Bristol and ECW under the Leyland banner, have also received only limited treatment.

Many sources of information have been used in compiling this work, though my own observations and personal recollections have formed the framework. Empirical data has come from the PSV Circle records and Gerry Tormey’s astonishing computer database of Bristol chassis, making it possible to use computer analysis to provide production statistics and other interesting data. A degree of inaccuracy is inherent in all such data, with no reflection on the compilers thereof, so while figures are quoted in many places, they should be treated as ‘give or take’ – but the relative picture is, I hope, correct. For ease of comparison I have combined figures for those operators who ran buses under several fleet names – for example Cheltenham District, Bath Services and Gloucester City figures are combined into the Bristol Tramways/Bristol Omnibus totals. York-West Yorkshire and Durham District Services are similarly combined into their parent fleet totals.

Vehicle and engine data mostly come from service manuals published by Bristol Tramways and Bristol Commercial Vehicles (BCV). Other information of this kind has come from the engine manufacturers, published road tests and vehicle owners.

Pictures have been drawn from my personal collection amassed from many sources. These are identified by the letters ‘AC’ in the captions. There are always gaps, so thanks go to the following for permission to use some of their images: the Bristol Vintage Bus Group, Adrian Baum, Stephen Dowle, Cliff Essex, Hugh Jones, Ray Simpson and Andy Strong. Where known, all photographers are identified in the captions.

I would like to thank the following, in no particular order: Ian Maclean of the Albion Register; Andy Strong and Richard Waters, who diligently proof-read the manuscript, corrected my mistakes and made some useful suggestions (if any errors remain, they are mine, not theirs, so do let me know via the publishers); also the following writers, who have recorded the history of Bristol Commercial Vehicles over the years, and who provided my bedtime reading as a teenager: Allan MacFarlane, Peter Hulin, Peter Davey, A. Alan Townsin and Martin Curtis. For ECW, Maurice Doggett is the unchallenged authority.

John A. Senior kindly made available the recordings of his interviews with George McKay, one-time chief engineer of the Tilling Group and board member of both Bristol and ECW. I was fortunate also to be able to pose some questions to Mr McKay personally.

I must also thank Brian M.K. Horner, retired Traffic Commissioner and former General Manager of several bus companies, for his insight into the Tilling Group and his observations on the LS and LH models.

Also Peter Jacques of the Kithead Trust, for his work for the PSV Circle, and for his patience in answering questions about the Tilling Group and other matters; and R. Hugh Eldridge, design draughtsman at BCV in Leyland days, who worked on the VR and B45 Olympian and fed my hunger for knowledge of bus engineering during our drinking sessions at the Royal Oak in Chipping Sodbury, so many, many years ago.

Preservationists extraordinaires include: Richard Belton, Peter Delaney, Calvin Everett, Paul Harrison, Sarah Hartwell, Adrian Hunt, Ian Mahoney, Craig Mara, Richard Masterman, the David Sheppards, both Snr and Jnr, Martin Southam, Simon Smart, William Staniforth and Mark Taylor.

I am also indebted to John Knox of Dover, who taught me much about buses nearly half-a-century ago, as did Peter Cook, custodian of a number of old Bristol buses and whose opinion on everything bus-related is always invaluable and genuinely entertaining.

My gratitude must also be recorded for an anonymous gentleman who travelled with us daily on the Yate bus during my teenage years, and who saved for me all sorts of documents, manuals, small bits of buses and magazines from BCV. The cast alloy Bristol scroll he gave me forty-four years ago now quite properly adorns the grille of my Bristol MW. Most importantly, he taught me how to distinguish by sound between the Gardner and Leyland engines fitted in Bristol Omnibus’ RELLs.

Finally a mention for my wife and daughters, who have tolerated my interest in ancient machinery, rust, oil and grease with only mild amusement and the occasional raised eyebrow over the years.

If I’ve missed anyone out, I sincerely apologize.

Nigel Furness, Frampton Cotterell,March 2013

CHAPTER ONE

BRISTOL AND THE BIRTH OF THE MOTOR BUS

THE CITY OF BRISTOL

Bristol is a medium-sized city, ranked eighth in the United Kingdom, with a population of about 428,000. The city lies on the tidal River Avon, which provided relatively easy navigation for large ships to access the Bristol Channel. A natural harbour was formed at the confluence of the rivers Frome and Avon, which allowed a thriving maritime community to be established. John Cabot set sail from there in 1497 and is said to have discovered Newfoundland. Slaves were traded in and out of Bristol until Humanism and Christianity put paid to that most abominable of trades.

Brunel made his home there, and improved the docks. He also built his Great Western Railway from Bristol to London, and the Bristol and Exeter Railway to Devon, thus helping to further establish the city as a centre of trade and commerce. The SS Great Britain was built there, in William Hill’s shipyard, and during the nineteenth century the city became a centre of heavy engineering. In time there came firms building railway locomotives, wagons and carriages, cranes, aeroplanes, motor cars and motor cycles – and the subject of our story, motor buses.

BRISTOL’S TRAMWAYS AND BUSES

The story begins with the establishment of The Bristol Tramways Company Ltd, registered on 23 December 1874 by George White, following the instruction of the Bristol solicitor, John Stanley. At first the company developed horse-drawn tramways in and around the City of Bristol, then on 1 October 1887 it became the Bristol Tramways and Carriage Company Ltd, when the Bristol Cab Company was acquired. By 1887 the latter had bought up the interests of the better cab proprietors, Bristol’s cabs having by then generally fallen into disrepute. The cab business was absorbed into the Tramways Company’s carriage department, started the year previously. This new side of the business brought to the company hansom cabs, broughams, wedding carriages, dogcarts and hearses, setting the scene for later operations that would include motor taxis (the famous Bristol Blue taxis) and omnibuses.

White became a principal figure in the company and decided to invest in motor buses in 1904, the same year in which they first operated regularly in London. He was aware that such vehicles had not yet proved themselves viable, so he ran them on the same routes as the horse omnibuses so that he could assess their strengths and weaknesses. White, like others, soon found that the off-the-shelf motor buses of the day were frail and unreliable contraptions, and decided to build his own.

Manufacturing began at a small works in Filton, on the outskirts of Bristol, in May 1908, though production moved to a site near the tram workshops at Bath Road, Brislington, around 1910–11, when White needed the space to start his aeroplane business. Body, chassis and engines were all manufactured in house. The first type was known as the C40 chassis and had a 13ft (3.96m) wheelbase and sixteen seats.

Bristol Tramways 76 (AE 779) was a 1909 Bristol type C40 with sixteen-seat body, seen here on service 18 at Durdham Downs, Bristol. It was later hired to the Corris Railway, an associated company owned by Sir George White’s Imperial Tramways.BVBG

GEORGE WHITE, VISIONARY AND PHILANTHROPIST

George White was born in 1854. Leaving school at fifteen, he found employment as a junior clerk in the Bristol law firm of Stanley and Wasbrough; by the age of sixteen he was in charge of the firm’s bankruptcy work. It is said that White’s time at Stanley and Wasbrough imbued him with the spirit of entrepreneurship, and was where he learned the principles of good business. It was John Stanley who instructed White at eighteen years of age to obtain parliamentary powers and form a syndicate to take over the City Council’s financially troubled Redland tramway. White later said of Stanley: ‘He didn’t pay me very much, but he was the best friend I ever had. He was the man who made me.’

Thus began the involvement with transport that would last until White’s death in 1916. In 1875 White formed a life-long friendship with James Clifton Robinson, who had been employed to manage the horse-drawn trams in Bristol. Robinson was an alumnus of the notorious George Francis Train, and from him had learnt the principles of running public transport systems; together they formed an indomitable team, with a finger in many transport pies. In 1876, White was elected to the Stock Exchange, where he specialized in transport shares.

Sir George White, Transport mogul.BRISTOL AERO COLLECTION

White always regarded himself primarily as a stockbroker, despite his later achievements. In the 1880s he became involved in tramways at Gloucester, Bath and York, and in various railway schemes; by 1892 he was a director of the Imperial Tramways Company, which had interests across the length and breadth of the country. His great ability was to recognize the mistakes that caused a business to fail, enabling him to pull them back from the brink of disaster. He pulled off several spectacular financial coups, including the sale to the public of Bristol’s famous brewery, Georges & Co., and obtaining a controlling interest in the Severn & Wye and Severn Bridge Railway, selling it to the Great Western and Midland Railways.

White was managing director of the Bristol Tramways by 1895, and in that year introduced the first electric trams in Bristol, and then in London in 1901. He became involved with the early London electric tube railway in conjunction with the American railway magnates Pierpoint Morgan and Charles Yerkes – though with the bill for its construction in its final stage in the Commons, White fell out with Morgan and sold his share in the endeavour to those opposing the scheme, causing great consternation amongst those involved.

White was a great philanthropist. He financed Bristol’s Royal Infirmary, a project deeply in debt, which he rescued with an extravagant fund-raising venture and cash from his own family’s pocket. He laid the foundation stone on 14 March 1911. The hospital remains, much enlarged, as a lasting memorial to White’s contribution to Bristol.

He developed a great interest in aviation, leading to his founding the Bristol Aeroplane Company, the Bristol Aviation Company and the Bristol and Colonial Aeroplane Company. In 1911 he cleared the Bristol Tramways bus garage at Filton of vehicles and converted the site for aircraft manufacture. With war in Europe looming, White persuaded the sceptical military authorities to adopt the aeroplane as an instrument of war. Having set up flying schools around the world, his Bristol school trained almost half the pilots available for recruitment at the start of the war. And if that wasn’t enough, the Bristol factory turned out over a thousand aircraft of various types for use by the military. He died suddenly on 22 November 1916, after a busy working day chairing two business meetings.

The C45 was a technically more advanced version of the C40. Bristol Tramways 1911 C45 number 73 (AE1156) had its open-sided twenty-two-seat charabanc body replaced with a similar capacity bus body by 1914.BVBG

The last word in touring coach travel before World War I: AE 2773. This 1912 twenty-two-seater C45 charabanc was Bristol Tramways 109.BVBG

Propulsion was by a 4-cylinder petrol engine, designated type X by the company. It has been suggested that the appearance and general design of these buses was based on the unsuccessful Thornycrofts and FIATs operated by the company during the period 1904–8, a reasonable enough assumption given that it is unlikely that White and his team would have had much exposure to other types of motorized omnibus by this date. Variations on the basic type included the C45 and C60 models, the C45 being more advanced in having shaft drive and a worm-gear differential as opposed to the chain-drive rear axle of the C40.

By the autumn of 1912 the Brislington site had been renamed the Motor Constructional Works, and production was building up. Two variations of the C-type were introduced in the same year, identified as the C50 and C65. It was at about that time that the Bristolian tradition of issuing ‘sanction’ numbers was introduced. A sanction was essentially an internal order for chassis production, and a convenient book-keeping device. Sanction numbers continued to be used until the end of production at Brislington, though during World War II the numbering series was interrupted and a new sequence prefixed with a W (for ‘Wartime’) began. This was because all bus manufacturing ceased temporarily in 1942, by order of the government; from then until 1946, all production had to be authorized by the Ministry of Supply. There were four wartime sanctions, numbers ‘W1’ to ‘W4’. Normal sanction numbering resumed after W4, with sanction 61 at the end of 1946.

This 1914 C50 twenty-eight-seat bus on The Downs at Bristol was Bristol Tramways 34 (AE 3196). It was withdrawn at the end of 1921 and converted to a lorry, in which form it was still in use in 1934.BVBG

The most powerful of the pre-World War I Bristol chassis was the C60, epitomized by AE 2551 when new in 1912, and posed here with a group of very serious-looking Bristol Tramways employees.BVBG

Bristol Tramways 23 (AE 3799) was a C50 twenty-four-seat bus built in 1914. Note its youthful conductor and more mature driver.BVBG

Returning to 1912, the early chassis were capable of being finished as either buses or lorries, a feature of all Bristol chassis production until the late 1920s. A new engine, designated the Y-type, appeared in 1913. This developed between 28 and 30hp from 4 cylinders of bore 4.25in (107.95mm) and stroke 5in (127mm), giving a capacity of 4.6 litres. It is thought this engine was developed primarily for goods use, but it was also used to power buses built for Bristol Tramways in 1913. World War I provided some interruption to bus production, as White’s efforts became more focused on aeroplane construction. Even so, a new model appeared in 1915 with a new 30hp engine designated the AW type – incidentally the first use of the classification system devised for Bristol chassis components that was used until the mid-1960s. This new model did not enter production, however, as the Brislington works was now assembling aeroplanes for the war effort.

After World War I, production of Bristol chassis did not properly restart until 1920. Bristol Tramways 190 was one of the earliest 4-ton buses. BVBG

NORMAL CONTROL AND FORWARD CONTROL

In a normal-control vehicle the driver is located, with the steering wheel and other controls, behind the engine and front axle, as in most motor cars. In a forward-control vehicle the driver is located alongside the engine (if it is a front-engine vehicle), ahead of, or over the front axle. The advantage of the forward-control arrangement for a bus or coach is that the body effectively has room for more passenger space, as the dead area alongside the engine is now taken up by the driver’s cab. However, moving the driving position forwards does introduce complications for the steering, particularly as in most designs the steering wheel is ahead of the front axle instead of behind it. In addition, access to the engine for maintenance and repair is now significantly reduced, as effectively the engine can only be reached from the passenger side of the chassis.

The 2-ton was Bristol’s first forward-control chassis. This 2-ton bus was outside Bristol Tramway’s Beach Road bus station in Weston-super-Mare, around 1927. The body would typically have had twenty-four seats.AC

4-ton twenty-eight-seat charabanc YA 905 was new in 1921. By the time this advertising shot was taken the charabanc’s original solid tyres had been replaced by pneumatics. Note the numbers on the seats, a guide to the capacity: seat number 3 was a tight squeeze!BVBG

The first Bristol double-deckers were on 4-ton chassis and had fifty-three-seat bodies manufactured by Dick Kerr of Preston. They were supplied to Kingston-upon-Hull Corporation. This is number 4 (AT 7353), one of nine supplied in 1923.BCV

The Bristol 4-ton chassis sold widely – this 1924 example with its thirty-seat Bristol bus body belonged to the Devon Motor Transport Co., Plymouth, number 41 (CO 6741). It is seen here posed with a group of DMT employees in white summer coats.AC/C. STACEY

After Sir George White’s death in 1916, his brother, Samuel White, became chairman of Bristol Tramways. However, bus production at Brislington did not resume until 1920, when a new chassis was introduced: this was the 4-ton, 14ft 6in (4.42m) wheelbase, normal-control model. In 1923 a lighter forward-control model, the 2-ton, was introduced.

Both the new chassis were powered by a new engine developed from the AW, the BW with 4.5in (114.3mm) bore and 5.75in (146mm) stroke, giving approximately a 6-litre capacity.

The 2- and 4-ton chassis were largely built for Bristol Tramways’ own use, though examples of each were exhibited at the 1923 Commercial Motor Vehicle Show as complete buses. They became popular with other operators, and Bristol began to establish a wide customer base as a result. West Riding Automobile Co. Ltd built up a sizeable fleet of forty-nine 2-tonners and forty-one 4-tonners by the end of 1926. Other customers included Lancashire United, Doncaster Corporation, Jersey Motor Transport, Devon Motor Transport and Hull Corporation, who had the only double-deck bodies on the 4-ton chassis.

Chesterfield Corporation with its fleet of seventeen 4-tonners and Manchester Corporation with six were additional customers for whom Bristol would become a regular supplier. Both 2-ton and 4-ton chassis were suitable for bus, charabanc and lorry bodywork including tankers, a large number of which were operated by Shell-Mex and BP.

A number of 2-ton chassis ended their days in this way – as dumper trucks for contractors. This one was still at work in 1949. HT 9976 was new in 1924 as a twenty-seat charabanc for Bristol Tramways, number O141.BVBG

CHASSIS AND PARTS IDENTIFICATION

With the introduction of the 2-ton and 4-ton chassis and the earlier AW engine, an alphabetic classification system for parts identification came into use. The first letter indicated the application or generation, the second the type of component. So, for example, ‘W’ is the identifier for an engine, so ‘AW’ was the first type of engine. Gearboxes were classified ‘S’, so the four-speed gearboxes fitted to the G and the J were known as JS, whilst the five-speed gearbox was known as KS.

As time went on, the basic system was further developed to include prefix and suffix letters and numbers to aid identification of the model, unit and part number. Hence the Lodekka gearbox breather part number was 269LDS – part 269, model LD (Lodekka), unit S (gearbox) – and the gearbox casing for the LS and MW single-deckers was part number LSS23. The numbers were often cast on to aluminium components, along with a tiny representation of Clifton Suspension Bridge, in case there was any doubt as to their origin!

The system continued until Leyland took over the Bristol plant in 1965. The author was told by a Bristol employee that this system was originally based on the location of parts in the stores, so ‘W’ was the section in which engines were stored, but the general consensus is that the letter referred to the major unit section on the chassis.

Unit Designators

A

Chassis frame

B

Not used

C

Change speed unit (gearchange)

D

Suspension

E

Front axle

F

Lubrication

G

Steering

J

Bonnet, cab, dash and front wings

K

Engine control

L

Electrics

M

Rear axle, final drive, rear hubs and rear brakes

N

Clutch

P

Transmission

Q

Brake and clutch operating gear and piping

S

Gearbox

U

Fuel system, breather pipes and exhaust

V

Radiator

W

Engine

X/Y

Not used

Z

Special tools

Chassis Identification

From 1923, Bristol identified chassis models using an alphabetic sequence that started with A and continued to the L-type introduced in 1937. Two prototype M-type chassis were designed and built just after the war, and were the last to be identified in this way. Subsequently a return to a descriptive style was used, starting with the LD (Lodekka) and LS (Light Saloon); the last model to use this style was the LH (Lightweight Horizontal). Further work at Bristol had Leyland project numbers with the prefix ‘B’.

Chassis numbering for the alphabetic series initially used just the letter followed by a serial number, starting from 101 – thus the first G was G.101. With the introduction of diesel engines in 1934, an engine identifier was included to differentiate between petrol and diesel. The initial letter of the engine manufacturer was also included in the chassis designation and the chassis number. A new sequence numbering system was introduced for each engine type, so the first 5-cylinder Gardner-powered G was GO5G.1 (the ‘O’ was included to represent ‘oil’ or diesel, to distinguish these from the petrol engines). When the Bristol petrol engines, the JW and NW, were fitted, the manufacturer’s letter was omitted: thus the petrol-engined G became a GJW or GNW.

Following the decision to manufacture only dieselpowered chassis, the ‘O’ was dropped, so the K with a 5-cylinder Gardner engine was a K5G. An exception was the SC chassis: this was fitted with the Gardner 4LK engine, but classified SC4LK to avoid confusion with the Gardner 4LW, as fitted in the L4G.

From 1938, the chassis numbering system was revised and was linked to the sanction number, so the first K-types had chassis number K5G.42.1 and the first L-type L5G.43.1. Further minor revisions in chassis numbering and designations took place in the 1960s and 1970s, and these are mentioned at the appropriate point in the text.

At least two 4-ton chassis survive, one as a lorry and the other as a bare chassis in the Bristol City Museum ‘M shed’ display. Being forward control, the 2-ton chassis initially carried bus bodies with a full-width front; however, in 1927 the first half-cab bodies of the familiar style were constructed for Bristol Tramways, in their own coach works at Brislington. Only nine were bodied as double-deckers, all by Dick-Kerr on 4-ton chassis, the rest being single-deck buses or charabancs. Early versions of both types of chassis had solid-tyred wheels, but production encompassed the introduction of pneumatic tyres and later chassis were so fitted.

The last 2-ton chassis were constructed for Bristol Tramways as late as 1932, and despite rapid advances in technology the chassis were still deemed suitable for smaller capacity buses. Of the 262 2-ton chassis, 232 were bodied by Bristol. The vast majority were twenty-seat buses, though fifty-eight twenty-seat charabancs were built. Of the remaining 2-ton production, eight were bodied by Charles H. Roe of Leeds and twenty-one as tankers, the remainder being miscellaneous goods vehicles.

Of the 651 4-ton chassis, most were bodied by Bristol as buses or charabancs, though with more variety of body styles, with single-entrance and dual-entrance buses and charabancs being produced, all to seat about thirty passengers. A total of 462 were bodied by Bristol for passenger-carrying use. Tankers accounted for another 118 4-tonners, and smaller numbers of other goods vehicle types were produced.

Both 2-ton and 4-ton chassis were subject to revisions during production. The most visible changes were the adoption of pneumatic tyres to replace the solid type from 1925, and a new radiator on the 1932 buses for Bristol tramways, which gave them a much more modern look as compared with the first production examples, as style started to creep into automotive design. The radiator design would be a trademark feature of early Bristol models, and would last until World War II. The final version of the 4-cylinder petrol engine fitted to these chassis was the EW.

The 2-ton and 4-ton buses and charabancs typically had service lives of around six to eight years. Rapid developments in the industry overtook them, however, and their simplicity made them obsolete as public service vehicles. But that wasn’t the end of the story, for many former 2-ton and 4-ton buses and charabancs were converted into lorries for further service, in which form some lasted until the first years of World War II, when age and petrol rationing finally killed them off.

BRISTOL TRAMWAYS JOINS THE TILLING GROUP

Following Samuel White’s death in 1928, the White family shares in the Bristol Tramways and Carriage Co. Ltd were acquired by the Great Western Railway (GWR). The GWR, indeed the railways companies in general, were always on the lookout to purchase interests in rival transport systems, just as they had done with the canals. The Railways (Road Transport) Act of 1928 took away their powers to operate buses in their own right, though they could maintain a financial interest in such companies.

The four mainline railways, the London Midland & Scottish (LMS), the London & North Eastern Railway (LNER), the Great Western Railway (GWR) and the Southern Railway (SR) companies jointly set up four bus-operating companies: Midland National (which never traded), Eastern National, Western National and Southern National, having previously purchased the National Omnibus & Transport Co., which they now divided amongst the three new working companies.

At the same time they were negotiating to buy into other provincial bus companies. Frederick Heaton, chairman of the Tilling Group, was dismayed by their continuing attempt to dominate both the rail and road transport scene, so he negotiated a deal with them such that shareholdings in the provincial bus companies were redistributed, and the railways were effectively limited to holding no more than 50 per cent of any one bus company. In 1929 the four mainline railway companies reached an agreement with Thomas Tilling Ltd and Tilling and British Automobile Traction Ltd, and the scene was set for the development of the Tilling Group.

The GWR was now the majority shareholder in the Bristol Tramways company, which contravened the 1929 agreement, though this did not come to light until 1931. The GWR’s shares in Bristol Tramways were then transferred to the Western National Omnibus Co. Ltd, by which time the three railway-owned bus companies – Eastern, Southern and Western National – were half-owned by the Tilling Group. Thus Bristol Tramways, as a subsidiary of Western National, became a member of the Tilling Group by default.

CHAPTER TWO

DEVELOPMENT OF THE BRISTOL CHASSIS

THE A-TYPE

Returning to technical developments, a new chassis, the A-type, was introduced in 1925. In contrast to the previous output from Brislington, the majority of A-types carried double-deck bodies. They reintroduced the type to the streets of Bristol, from which they had been absent since the earliest days of motor buses in the city. The wheelbase was 16ft (4.88m), and the design was intended for either single-deck or double-deck bodies. Use of an underslung worm differential rear axle, combined with the chassis frame cranked downwards between the axles, helped to lower the floor line, as compared with the 2-ton and 4-ton chassis. The engine for the A-type was a 4-cylinder, long-stroke (6in) petrol engine, an 85bhp development of the EW and classified FW.

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!